Access to free period products in educational settings during the 2018-19 academic year: monitoring and evaluation report

We carried out an evaluation, supported by COSLA and the Scottish Funding Council (SFC), of access to free period products in educational settings during the first full academic year of delivery, from 1 September 2018 to 31 August 2019.

3. Key Findings

Local Authorities

Monitoring data

Monitoring data on spend and the quantities and types of products purchased was received from all 32 local authorities covering the period 1 September 2018 to 1 February 2019 and from 31 local authorities covering the period 2 February to 31 August 2019. Qualitative data on approaches to delivery was received from all 32 local authorities covering the period 1 September 2018 to 1 February 2019 and from 31 local authorities covering the period 2 February to 31 August 2019. Where possible, where data was not received for the period 1 September 2018 to 1 February 2019, data received for the period 1 September 2018 to 1 February 2019 has been used to provide a more complete overview of delivery.

How was access to free period products being delivered in schools?

Local authorities reported having a range of delivery models in place to provide access to free period products to pupils in schools. Almost all local authorities reported that schools in their area were providing period products in storage containers/baskets in pupil toilets (94%) and just under three-quarters were providing free period products at pick-up points on school premises (75%). A summary of delivery models implemented by local authorities is provided in Table 2.

All local authorities reported having at least one delivery model in place, although most local authorities were providing more than one; there was a median of three delivery models implemented in each local authority. A number of different delivery models in place within a single local authority was often due to the autonomy given by local authorities to individual schools to decide how they make products available to their pupils. Local authorities reported that the delivery approach within individual schools are likely to depend on a range of factors, including: available space and facilities in pupil toilets; age of pupils accessing products; and concerns about misuse or vandalism of products. Some local authorities reported, for example, that, unlike secondary schools in their area, some primary schools did not have the space in pupil toilets to provide period products so opted to provide products at designated pick-up points.

| Number | Percentage | |

|---|---|---|

| Storage containers/baskets in pupil toilets | 29 | 94% |

| Pick-up points on school premises | 23 | 75% |

| Pre-prepared packs | 13 | 41% |

| Pick-up points in community settings | 9 | 28% |

| Free vending machines/dispensers in toilets | 3 | 13% |

| Online ordering | 1 | 3% |

| Not known (no response) | 1 | 3% |

Establishing universal access in school settings, achievements and challenges

The majority of local authorities reported achieving full roll-out of provision by September 2019, typically defined as providing a range of period products in all eligible schools. However, whilst planned roll-out had been achieved, several local authorities reported plans to further expand delivery in various ways, including:

- Increasing the variety/brands of available disposable period products.

- Introducing or increasing the provision of reusable/environmentally-friendly products.

- Increasing awareness and promotion of the availability of provision to pupils and parents.

- Increasing pupil uptake of products and, as a result, product orders from some schools.

- Increasing the delivery of educational programmes on menstruation in schools to tackle stigma and normalise menstruation.

- Increasing engagement with pupils to gather their views on available provision and ways in which it could be improved.

Were free period products being made available to school pupils outside of term-time?

All local authorities reported having arrangements in place to provide access to period products outside of term-time for at least some of the school holidays during the 2018-19 academic year.

The vast majority of local authorities reported that schools in their area were encouraging pupils to take bulk supplies of period products (i.e. 'stock up') in advance of the school holidays (88%) and just over half (53%) reported that period products were accessible in community settings targeted at young people (e.g. youth centres, libraries, leisure centres, swimming pools). See Table 3 for a summary of ways in which period products were made available to pupils outside of term-time.

Most local authorities were providing access to period products during the school holidays through at least two different approaches. As seen for term-time delivery models, approaches to holiday provision was often devolved by local authorities to individual schools, which contributes to variability in how period products were made available to school pupils outside of term-time within local authority areas. For example, local authorities reported that some schools within their area remained open and accessible to pupils during the holidays whereas other schools were closed and therefore could not offer access to free period products on the school premises during the holidays.

| Number | Percentage | |

|---|---|---|

| Pupils encouraged to 'stock up' in advance of the holidays | 28 | 88% |

| Products accessible in community settings | 17 | 53% |

| Prepared packs or bags of products | 12 | 38% |

| Schools open during the holidays | 12 | 38% |

| Online ordering | 0 | 0% |

| Monetary grants paid to pupils | 0 | 0% |

| Not known (no response) | 1 | 3% |

Were there any promotional activities to encourage uptake of free period products among school pupils?

The majority of local authorities reported undertaking some promotional activities, either delivered by the local authority themselves or delivered by schools in their area, to encourage pupils to take free period products and to provide education around menstruation. Reported promotional activities reported included the provision or distribution of:

- Printed promotional materials, including leaflets, flyers and posters.

- Assemblies and PSE lessons delivered by teachers, school nurses or pupils themselves.

- Targeted promotion to specific families by external partners or organisations, including by school nurses and family support workers.

- Promotional articles in local newspapers, council websites and on social media.

- Proactive contact with home-educated pupils, parents and carers.

A small number of local authorities provided examples of direct pupil involvement in promotion, as summarised by the following quotes:

- "Girls made a film to tell the story in their school. This was shared with COSLA and the Communities minister. This film will now be the basis on which we launch our next phase of our project. Our next phase will be led by girls and their ideas."

- "We established leadership groups in each of the schools – these were S2 girls, in the main. The girls led assemblies, ensured that posters 'advertising' access were visible and also advised on the best method of dispensing."

In addition to advertising the availability of free period products, some local authorities reported wider beneficial effects of promotional activities on culture change, tackling stigma and normalising menstruation:

- "The promotion has had a huge impact on culture change, reducing stigma and increasing boys and girls confidence to speak about periods and we are proud of this achievement"

- "These are positive steps in increasing the promotion of a culture of change where we are being encouraged to talk more openly, and therefore de-stigmatise the subject making it 'no big deal'. This process of culture shift will take time."

What types of period products were purchased and distributed to school pupils?

The majority of local authorities were making a variety of period product types, brands and absorbencies available to school pupils, including day/night products, applicator and non-applicator tampons and products specifically developed for teenagers. Several local authorities reported gathering feedback from pupils on the range of period products made available.

All 32 local authorities were making at least one type of sanitary towel available to pupils and 30 local authorities were making at least one type of tampon available.

Thirteen local authorities made reusable period products available, comprising five local authorities who provided menstrual cups, two local authorities who provided reusable pads and six local authorities who provided both menstrual cups and reusable pads. Two additional local authorities reported that reusable products were available to schools upon request, but they had not been taken up on the offer during the reporting period.

Eight local authorities were making 'starter packs' available, which comprise a variety of period and non-period products. A minority of local authorities reported using funding to provide additional items related to menstruation, including underwear and tote bags to allow pupils to collect bulk supplies of products.

How many period products were purchased by local authorities for distribution in schools?

Based on data provided by 30 local authorities, at least 6,746,065 disposable period products[21] were purchased during the 2018-19 academic year for distribution in schools. To put this in context, the number of products purchased by local authorities reflects a median of 32 products per female secondary school pupil[22] with half of local authorities purchasing somewhere between 24 and 60 products per female secondary school pupil. This figure reduces to 23 products per pupil in the full estimated menstruating school pupil population.[23]

In addition, 2,876 menstrual cups were purchased by 11 local authorities and 4,970 reusable pads were purchased by eight local authorities.

These figures do not include period products contained within the 9,373 'starter packs' purchased by eight local authorities.

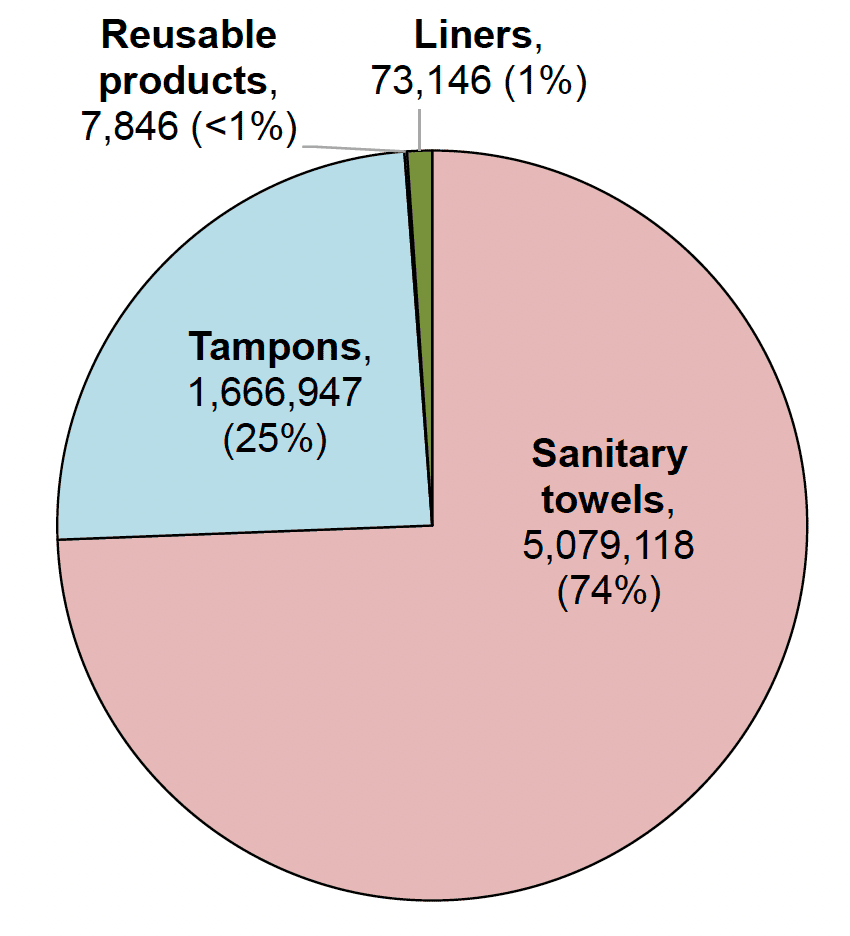

As shown in Figure 1, sanitary towels were purchased in the highest quantity, comprising 74% of all period products purchased. Reusable products – menstrual cups and reusable pads – comprised a very small proportion of the total number of period products purchased, however it is noted that the annual per pupil requirement of reusable products is likely to be significantly lower than disposable period products.

What is the uptake of period products in schools?

The majority of local authorities were not able to report uptake levels within schools in their area. There were a variety of reasons reported, including:

- Devolved purchasing/delivery to schools does not allow for estimation of the products distributed or taken by pupils.

- The provision of period products in pupil toilets, a common delivery model reported by local authorities, does not readily allow for an audit of the number of pupils accessing provision and the number of products taken by each pupil.

- Difficulties on how best to calculate uptake.

- Lack of capacity within local authorities to collate information from all, or a large enough sample, of schools within their area due to the time-consuming nature of this task.

Among the minority of local authorities that reported an estimated uptake figure, there was considerable variability in how this figure had been calculated. Given the lack of available and consistent data on uptake, an estimate of uptake was calculated by Scottish Government analysts for 30 local authorities based on the reported number of disposable period products purchased during the 2018-19 academic year.[24]

This showed that the number of disposable period products purchased by these local authorities would support the equivalent of 17% of secondary school pupils in these local authorities to access their full annual disposable period product requirement.[25]

However, there was substantial variability across the 30 local authorities in their estimated uptake rates calculated in this way. For example, the median uptake was 11%, with estimated uptake in half of all local authorities ranging between 8% and 20%. These estimated uptake levels are lower than the originally anticipated 35% of pupils accessing period products from their schools to meet their full annual product requirement, on which funding to local authorities is was based during the 2018-19 academic year. Two local authorities purchased period products in quantities that support an estimated uptake rate in excess of 35%.

It is important to highlight, however, that these figures reflect an estimate only and the interpretation of these figures require a number of assumptions, including that all disposable period products purchased by local authorities were distributed and taken by pupils. In addition, in line with assumptions made in the calculation of funding allocations, uptake is defined as the proportion of pupils taking their full annual proportion requirement. In reality, the pattern of usage is likely to reflect a larger proportion of pupils taking a smaller proportion of their annual requirement (see findings of the student survey discussed later).

Consistent with the estimated uptake levels calculated by Scottish Government analysts, some local authorities reported that uptake had been lower than anticipated:

- "Schools were encouraged to send letters, texts and tweets and display posters. Uptake was still lower than expected so this did not have a very positive impact."

- "During holidays pupils were directed to Youth Centres, but uptake seemed limited."

- "To date posters around the school and presentations by school nurses on their visits. It is not known whether they had any impact on uptake which has been very low."

Many local authorities reported that they expected uptake to increase or reported factors that are likely to influence uptake in schools including:

Tackling stigma and promoting 'period dignity'

"Pupil uptake of free sanitary products in the Secondary Schools where the Head Teacher is actively enthusiastic about the scheme is significantly higher."

- "We anticipate an increase in uptake as the education around this becomes more established. As we continue to address dignity and stigma we expect an increase."

- "Uptake has increased as we have worked harder at the education side of things and ensuring that access is discreet and readily available."

Engagement with pupils and students in shaping delivery

- "The involvement of children and young people to shape and design the model, choose the products and make continuous improvements within their schools has been very positive– pupil voice"

- "The roll out was slow and delayed so this limited uptake. The more products that become available and more engagement with young people should increase this figure"

Ensuring that period products are easily accessible

- "Because our initial models did not have period products in the toilets, there has not been the uptake that we initially anticipated. This is starting to change as some of our schools are placing the products in the toilets."

Acknowledging that need may differ across schools, depending on the menstruating pupil population

- "Some primary schools were concerned about lack of uptake, although this could be attributed in several cases to the number of girls having reached puberty in the school."

How were local authorities purchasing period products for distribution in schools?

Local authorities had a variety of purchasing models in place, with half of all local authorities (50%) reporting that they were purchasing period products centrally and distributing these to schools. Table 4 provides a summary of purchasing models in place by local authorities.

Over a third of local authorities (38%) reported that they had a purchasing model in place that was not captured by the response options so provided some details as a free-text response. These included:

- Purchase and distribution of products to schools by an external organisation.

- Some schools using donated products rather than ordering products.

- Products purchased in bulk and held in council stores for distribution on an ad hoc basis to schools.

| Number | Percentage | |

|---|---|---|

| Products purchased centrally in bulk in advance and distributed to schools | 16 | 50% |

| Schools supplied with funding and ordered products themselves | 9 | 29% |

| Products purchased centrally based on an ad hoc basis following orders from schools | 7 | 23% |

| Other | 12 | 38% |

| Not known (no response) | 1 | 3% |

What was the unit price of period products purchased by local authorities for distribution in schools?

At the time the research was undertaken, the median unit price (middle unit price) was 11.3p per disposable period product[26] purchased by local authorities, comprising 8.4p per sanitary towel and 13.4p per tampon. There was large variation of unit prices; half of all local authorities purchased sanitary towels with unit prices between 7.4p and 11.0p and tampons between 9.7p and 17.3p. Among the local authorities who purchased reusable period products, there was a median unit price of £3.59 for menstrual cups and £2.45 for reusable pads. Variation in unit prices depends on a range of factors, including supplier arrangements, brands; and quality of products provided within each local authority. Table 5 provides an overview of the unit prices of each period product type provided by local authorities for distribution in schools.

| Lower quartile | Median | Upper quartile | |

|---|---|---|---|

| (25% of unit prices are lower than this value) | (middle value) | (75% of unit prices are lower than this value) | |

| Sanitary towels[27] | 7.4p | 8.4p | 11.0p |

| Tampons[28] | 9.7p | 13.4p | 17.3p |

| Menstrual cups[29] | £3.59 | £3.59 | £3.59 |

| Reusable pads[30] | £2.36 | £2.45 | £11.68 |

| Liners[31] | 3.7p | 4.5p | 5.3p |

What did local authorities spend purchasing period products for distribution in schools?

The total spend on period products across all 32 local authorities[32] was at least £734,320 (net VAT). The majority of this spend was incurred in the first five months of the academic year, with 74% of reported spend on period products (£541,189) incurred between 1 September 2018 and 1 February 2019. This is consistent with monitoring data showing purchasing products in bulk in advance was the most common purchasing approach implemented by local authorities (see above).

To understand the scale of spend on period products during the 2018-19 academic year, spend was compared against longer-term funding distributed by the Scottish Government to local authorities to support the purchase of period products for distribution in schools. Local authorities received a total of £3 million to support the purchase of period products for distribution in schools between 1 August 2018 to 31 March 2020[33]. As the 2018-19 academic year does not cover the whole of this period, a proportion has been calculated to approximate anticipated spend at September 2019 assuming full spend of the 2019/20 funding allocation by end of March 2020. Assuming a similar rate of spend on period products throughout the financial year, the anticipated spend by the end of 2018-19 is in the region of £2 million.[34]

Based on data from all 32 local authorities, spend on products during the 2018-19 academic year reflects 61% of the 2018/19 product funding allocation, reducing to 37% of the £2 million anticipated spend by the end of the 2018-19 academic year.[35]

There was considerable variability across local authorities in product spend:

- When compared against only the 2018/19 product funding allocation, the median spend was 50%, with half of all local authorities spending somewhere between 34% and 100%.

- When compared against the anticipated spend by 1 September 2019, this reduces to a median of 31%, with half of all local authorities spending somewhere between 21% and 61%.

What did local authorities spend on development and administration?

In addition to the purchasing on period products, local authorities incurred additional costs in providing access to free period products in schools. This additional costs related to one-off development (set-up) of provision and ongoing administration, including delivery, promotion and staffing.

Based on data from all 32 local authorities[36], the total spend on development and administration across all local authorities was at least £490,260 (net VAT). Additional spend gross VAT (20%) is presented in Footnote [37].

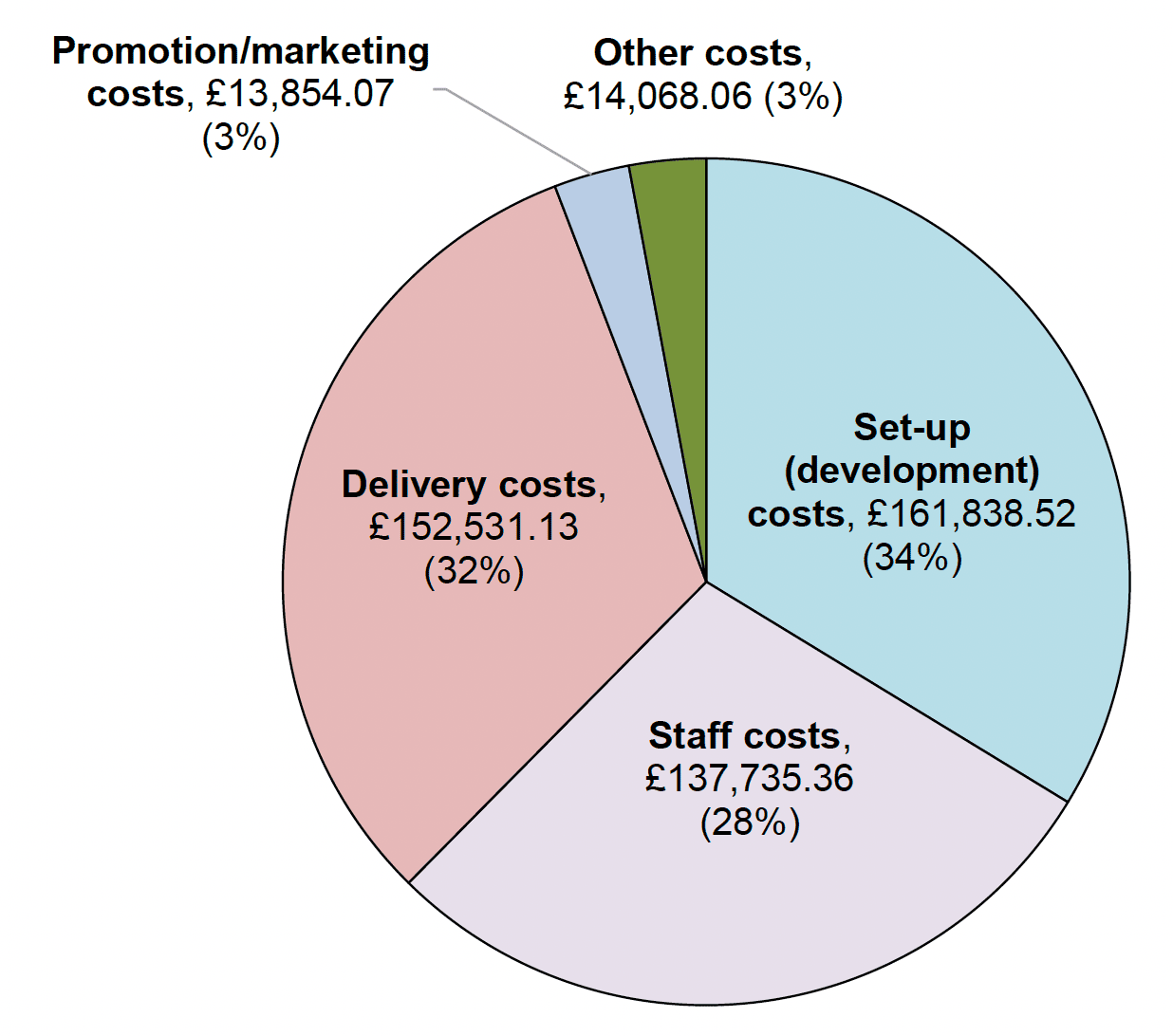

Figure 2 provides a breakdown of spend on development and administration. As shown, development costs, including the purchase of free vending machines and storage boxes, comprised just over a third (34%) of this figure. Ongoing delivery costs include the maintenance of dispensing machines, sanitary bin waste disposal, and facilities management. Promotion/marketing costs include the purchase of teaching materials, poster, badges and the running of events to increase awareness of provision, provide education and tackle stigma.

To understand the scale of spend on development and administration during the 2018-19 academic year, spend was compared against the funding distributed to by the Scottish Government to local authorities to support development and administration. During the 2018-19 academic year, local authorities received a total of £910,000 to support development and delivery, comprising £432,000 to support administration between 1 August 2018 to 31 March 2020[38] and an additional £478,000 one-off funding allocation provided in August 2018 to support policy development.

Following the approach set out above for product funding allocations, spend on development and administration of £659,000 would be expected by the end of the 2018-19 academic year if the whole development and administrative funding allocations were spent at a constant rate by 31 March 2020, reflecting:

- Full spend of the one-off development allocation (£478,000).

- Spend on ongoing administration in the region of £181,000 to cover the period 1 August 2018 to 1 September 2019.[39]

Thus, local authorities' reported spend on development and administration reflects 75% of the total development and administration allocation provided in 2018/19 and 64% of the spend on development and administration that would be expected at 1 September 2019.

What worked well in local authorities' delivery?

Local authorities were asked to report what they felt had worked well in their chosen delivery approach. Thirty local authorities provided a response. This revealed two key themes:

Pupil involvement in the development and delivery of provision, as illustrated by the following quotes:

- "Working with girls in our secondary schools and Youth Work services, we were able to define what the girls' wanted, or didn't want and make sure we were able to cater for them."

- "The involvement of children and young people to shape and design the model, choose the products and make continuous improvements within their schools has been very positive– "pupil voice"."

- "Our delivery model has worked well and is improving with increased leadership from pupils. The involvement of the pupils to lead this, and younger pupils in particular has been a strength of our approach."

Taking a flexible local approach, as illustrated by the following quotes:

- "Schools can order what they need and when. They can change if needed and are not committed to limited products. This has had an impact as girls are getting access to quality products that they have had a part in deciding on."

- "The model allows flexible approach to suit schools requirements."

- "The decentralised model, devolving funding and ordering responsibility to schools was the preference of schools, and logistically the most pragmatic option. While central resources and guidance were provided, the approach has also empowered schools to implement the models that best suit them and their pupils."

What worked less well in local authorities' delivery?

Local authorities were asked to report what they felt had worked less well in their chosen delivery model. This revealed three key themes:

Lack of data around uptake or delivery in schools, as illustrated by the following quotes:

- "The only real issue is that we have no specific data on uptake, beyond what our invoices can tell us. However, this is in-keeping with our light touch approach."

- "The downside of the approach above is the extent to which data is then held at individual schools level and there is no central record in relation to volumes ordered, volumes issued and held."

- "It is also difficult to monitor uptake as require communication with 170 plus schools."

Challenges around the procurement and delivery of products, especially in small schools, as illustrated by the following quotes:

- "very small schools and those in rural areas experienced difficulty in purchasing products. For this reason, we have sought bids from schools for any additional storage requirements and products. We will then deduct the cost of products purchased centrally and devolve the remainder to schools on a per capita basis to enable them to top-up products according to their needs."

- "In some cases remote locations and low pupil numbers meant that small numbers of sanitary packs required got temporarily lost among other deliveries for remote schools. This has got better now that all staff are familiar with system."

- "Distribution was cumbersome due to the sheer quantity of products required for this authority. Primary schools had to arrange for staff to collect from local Secondary school."

School engagement, as illustrated by the following quotes:

- "Getting all schools on board has been challenging. Whilst all offer the products we want to see more taking on the guiding principles and allowing the girls to lead."

- "Little control over how schools choose to distribute. Will do more work this year to encourage schools to make products more freely available and promote the offer "more."

How burdensome was it for local authorities to administer the access to free period products scheme/the means for schools to purchase products?

There was considerable variability among local authorities in the extent to which administering access to free period products scheme was perceived to have been burdensome. Among the local authorities that reported some burden, the majority reported that the initial set up of the scheme had been time consuming but the burden had reduced once systems were established, as illustrated by the following quotes:

- "It has been quite time consuming (mainly my own time) to get established but we now have workable systems in place."

- "Once our model was agreed it has become a straightforward administration and promotion task."

- "Procurement was difficult at the start but now that purchasing routes are in place it is no longer an issue."

Two local authorities noted difficulties around the parallel administration of access to period products in schools and community settings:

- "Rollout to public buildings and to schools is being done jointly as having the same ordering and distribution arrangements appears the most practical solution, particularly as many schools are community schools. However, having separate budgetary arrangements and reporting requirements has complicated this and adds to requirements on officer time."

- "Some confusion has arisen with the community roll out as we have targeted Nurseries as a place for the Community provision…this has confused some as the administrators in some nurseries are also those in the attached schools."

Were there any logistical/operational challenges faced by schools in distributing products?

The most commonly reported logistical challenge concerned storage of products within school toilets, as illustrated by these quotes:

- "The toilets in all of our schools are designed differently. Some are extremity [SIC] small and therefore no room to store and display products. Therefore we cannot get the same dispenser units in the cubicles or out-with the cubicles. This means that the dispenser units in each toilet area in all schools will need to be bespoke for each school, which it time consuming and challenging to scale up across the city moving forward."

- "Some schools indicated that there was some compromise to privacy as girls have to access products in open areas of toilets as they are unable to accommodate them in individual cubicles."

Additional logistical challenges were reported around:

- Janitorial and cleaning staff not able to re-stock products, impacting on where products could be placed in schools.

- Schools highlighting the time required to order products, fill up units and check and keep units full.

- Some of schools being owned by public private partnership companies making it challenging to put in place storage, such as shelves.

- Challenges for primary schools around ordering small quantities of products.

Local Authority workshop

A workshop, attended by a nine representatives from seven local authorities, was held on 21 February 2020. The purpose of the workshop was to supplement the monitoring data, discussed above, with additional qualitative data on 'what works' in delivery of access to free period products in schools (and why) from the perspective of local authorities. The workshop was organised and supported by COSLA, in collaboration with the Scottish Government. The workshop had three key aims:

1. To develop further understanding of the effectiveness of different delivery models across local authority areas.

2. To develop further understanding of the challenges faced by local authorities in delivery access to free period products in schools and how these challenges were resolved.

3. To develop further understanding of the causes of variable uptake in schools.

The rest of this section summarises the key themes arising from discussion of delivery approaches, management approaches for purchasing and distribution, and variable uptake across local authorities.

Exploring different delivery models

Some local authorities adopted a flexible delivery approach to enable schools to decide on the delivery models that best suited their venues. The majority of schools opted for the provision of products in pupil toilets. However, some schools continue to hold stock in school offices due to not having the facilities to provide products in pupil toilets, and persistent concerns about vandalism and misuse of products

There may be some limitations of using vending machines to deliver access to free period products. Challenges were noted around ensuring vending machines were adequately stocked, the potential for stigma and embarrassment, and vending machines appearing dated. One local authority reported transitioning away from the use of vending machines in favour of providing products in toilet cubicles.

Engagement with pupils was undertaken by some local authorities to shape delivery, including through focus groups or through peer-led distribution of products.

Exploring different management approaches for purchase and distribution

Approaches to the provision of period products can be broadly divided into delivery though education-based teams, including devolving provision to teachers, and delivery through facilities management teams.

Delivery through education-based teams was often characterised by the additional provision of wide ranging educational opportunities (e.g. to tackle stigma around menstruation, encourage cultural change).

Some challenges were noted around the implementation of an education-based approach, including around recording data where product distribution is led by pupils, ensuring consistency in adherence to the guiding principles and the time requirement for school staff to facilitate pupil groups.

Some limitations of a facilities management approach were identified, including in reducing the involvement of pupils in shaping delivery contributing to lower uptake and the reluctance among some facilities management staff to restock products and implement novel delivery approaches.

Specific challenges for small primary schools were identified, where small per capita budgets made the acquisition of products locally challenging.

Exploring variable uptake

Making products available in school offices may be a barrier to uptake. Some schools continue to hold stock in school offices due to not having the facilities to provide products in pupil toilets.

Reduced uptake may be due to a lack of awareness of provision among parents. Efforts to raise awareness undertaken by local authorities included running a social media campaign for parents, the distribution of 'starter packs' for at-home use with an aim of increasing parents' awareness of the availability of products, and the provision of products at parents evenings.

The framing of available provision was identified as an important factor in increasing uptake – moving away from provision as tackling period poverty to period dignity (i.e. universal provision).

The involvement of teachers was identified as a key factor in increasing uptake. Some additional work may be beneficial with teachers in some schools to tackle stigma, encourage the delivery of education on menstruation and increase the accessibility of period products in schools.

Local authorities were keen to receive a methodology to allow the calculation of uptake. Local authorities received reports of lower than expected uptake from schools but had no method of comparing uptake across schools. It is not possible to count the number of products distributed to pupils, but product spend may lack accuracy.

Case studies

Case studies for three local authorities – Argyll and Bute, City of Edinburgh and Dundee – were prepared by COSLA in February 2019. These case studies provide an overview of period product provision within selected schools and the challenges encountered in delivery during the 2018-19 academic year.

Case study one: Argyll and Bute

The 89 schools in Argyll and Bute serve some of Scotland's most rural and isolated communities; of its 79 primary schools almost half have a register of 25 or less. Service delivery of any kind incurs unique logistical challenges. In looking to provide access to free period products, each local school has purchased its own products and devised its own delivery models to best suit the needs of its pupils. The examples below demonstrate the approaches taken in sample schools and considers how implementation will be developed as the initiative progresses.

Dunoon Grammar School

With a school roll of 674 pupils, Dunoon Grammar School is situated in the east of Argyll and Bute. The school approached the roll out of access to free period products by conducting surveys with small groups of S4 and S6 pupils as well as parents to establish the types of period products the young people would want and where would be best to place them. As a result, period products were ordered by the school and placed in multi-draw storage units in female, gender neutral and disabled toilets, and in physical education (PE) and learning support departments. Period 'starter packs' were also provided to S1 and S2 'nurture group pupils' whom are in receipt of free school meals. The school was planning to conduct further consultation at the end of the 2018-19 academic year to ensure the period products provided and their placement in the school was effective, and was also looking to expand the provision of starter packs to S1 pupils.

A S6 pupil at Dunoon Grammar School reflected on the impact of the provision of free period products during the 2018-19 academic year:

"Having pads and tampons available in the toilets is really positive, I've overheard lots of girls talking about how handy it is. I think it normalises periods, which is really important; people aren't as embarrassed about them and it's taken away the stress and anxiety from not being able to get the products that they need. I know a few people who weren't coming in when they had their period because they didn't have stuff at home and now they can get it here they are coming in more."

Lochgilphead Joint Campus

In central Argyll and Bute, the provision of free period products at Lochgilphead has been developed and led by a 'pupil voice' group, comprising ten girls representing all school years. A S6 pupil described how they have approached it and their views on how successful it has been:

"In the beginning we presented an assembly and we talked about making sanitary products free in school, why it was happening and how important it was. We also did a survey to see what products people would want. We bought the products in bulk and put them all around the school in individual toilet cubicles where it is private, and people feel like they can take them. There are sanitary products and different things you might need like waste bags. We decided hanging bags with pockets would be best for storage. We have also left out full packs of products in case people need to take them home. We have put posters on the doors where products are available and even have some in the staff toilets, which students can go and use in an emergency. We have a pupil rota to stock up the products and we do it weekly."

The boys have been involved too. When we gave our talk on period poverty and we presented the topic to them. They were shocked at the cost of sanitary products and have been really supportive and empathetic. They also covered some men's health topics like Movember and testicular cancer, so they had conversations about men's health as well. The tutorial class built some cabinets to keep products in! These cabinets have gone into all of the disabled toilets, so people can help themselves there too.

It is working really well and is really appreciated; our stocks are going down so people definitely need them. A couple of people have said that its really helped them a lot because they are not able to get any anywhere else. I've really enjoyed being involved in this as I feel like I am helping people. Our next job is to provide more sanitary bins!"

Kirn Primary School

Kirn Primary School, also located in Dunoon, has a school roll of 285 pupils. At the end of the 2017-18 academic year, the school consulted with a group of P6 and P7 girls on the initial set up of free period product provision. They discussed what period products should be made available and where would be appropriate for easy access for all pupils. The discussion also generated feedback about sanitary bin provision in school, which the girls felt was inadequate. As a result of this collaboration, a sanitary bin and box with supplies (sanitary towels, nappy bags, deodorant, wet wipes and a guidance leaflet) was located in the disabled toilet between the P6 and P7 classrooms. The young people felt that that school was the most sensible place for them to access period products as they could get them without deviating from their normal routine.

Parents were informed that education on menstruation would take place. All P6 and P7 girls took part in a discussion that focused on menstrual cycle but also allowed the girls to familiarise themselves with sanitary products, how to use them and apply them to underwear.

It has been observed that uptake of the free period products is not high and it is topped up termly. Staff feel that having free period products available has removed the requirement for pupils to ask staff for products.

Challenges in Argyll and Bute

In addition to challenges related to achieving cultural change around menstruation, which are likely to be experienced within many local authorities, the key challenge of providing access to free period products in Argyll and Bute is one of geography:

- Getting products to the most rural schools can be more expensive than purchasing the products themselves. Economical means to transport the products have had to be identified.

- As some of the primary schools are very small they currently do not have any female pupils old enough to be eligible for the funding (11 years and above). This will change as the community changes and girls enter and leave different educational institutions

Given the unique challenges of in Argyll and Bute, schools and their pupils taking on responsibility for the development and delivery of access to free period products has been the most appropriate model. Consequently, delivery of the provision has been approached differently in different educational institutions. Work moving forward will continue to encourage each eligible school to ensure free period products are available to all pupils across Argyll and Bute.

Case study two: City of Edinburgh

The provision of free period products has been well received by schools in the City of Edinburgh. Funding to make free period products available was devolved to each eligible school by City of Edinburgh council; the descriptors below detail the approach a sample of schools have taken, why and with what impact.

Craigroyston Community High School

Situated in the north of the Edinburgh, most of the pupils at Craigroyston Community High School live in the most deprived areas (Scottish Index of Multiple Deprivation (SIMD) deciles 1 and 2).

Prior to the Scottish Government commitment to make free period products available in all schools, pupils at Craigroyston Community High School who required period products would have to request them from guidance staff. Staff reported often payinf=g for these products themselves. On commencement of the Scottish Government policy, Craigroyston Community High School held a focus group with pupils from S1-S6. Pupils reported that they would like period products to be more readily available for them, without having to ask school staff as this caused embarrassment. Following this, a cupboard of free period products was provided in the main girl's toilets, in the changing rooms in PE and in a toilet near the guidance department. These are restocked regularly and contain a varied range of period products,including liners, different sizes of sanitary towels; day and night towels; and tampons in different absorbencies. Pupils are also encouraged to take enough period products to meet their needs, there is no limit.

In addition to provision in pupil toilets, boxes of period products have been distributed to all pupil year groups through PSE lessons and time has been put into the curriculum to teach the younger year groups the difference between each type of sanitary towel and how tampons can be used, including their advantages and risks. Pupils identified members of staff that they would go to if they had a problem relating to their periods and referrals can be made to the school nurse if appropriate.

Tynecastle High School

Tynecastle High School is a diverse inner-city high school; its 609 pupils speak 42 different languages between them, and 17% of pupils currently receive free school meals. Pupils reported how access to free period products has been organised and what young people think of the scheme:

"There are individual products, a mixture of tampons and towels, available in toilets in every faculty as well as the disabled toilets which are gender neutral. We have some pupils in the school who are transitioning so we spoke with them and our LGBT group to plan where would be the best place to put these. Toilets where free sanitary protection is available have a poster on the door and there is of a list of teachers, from who we can collect boxes rather than individual products, on the poster too. We think that it's important that you can collect them in bulk if you want so you can get them from the named teachers or there is a classroom in the first floor where you can help yourself to boxes of tampons or sanitary towels. There are stocks available in PE too. It's good to be able to get them in more than one way. We check supplies a few times a week and know they are really being used as we are doing lots of topping up. People are coming back again and again for boxes of products; we know that some might also taking them home because none of their family have any and it will be good when they can collect these in places out of school too. Both teachers and pupils see the differences this has made, the biggest one is that the young people no longer having to go to the, often busy, welfare office to ask for products. It has removed the embarrassment, people can access sanitary protection where and when they need to but also know where they can go for help if they want it. We don't know if it has improved school attendance, it's very hard to tell, though some of the girls think that it might have done. What it has done is help remove the fear of being found out because there is a smell or a leak through your leggings and that will help attendance and participation, particularly in classes like dance where we wear leotards and that sort of thing is more of a worry! Next, we are looking at buying reusable products and promoting these through our eco- friendly group. We think people are a bit sceptical about these products because they are new, so it may take a little while to get people to take them. We are also going to provide 'my first period kits' for S1s and work with them when they move from primary to secondary, so they are comfortable with the topic and know where they can collect products in our school".

Broughton High School

Broughton High School, located in the north of the City of Edinburgh, educates young people from diverse backgrounds. In 2018, it served the second highest number of children from the most deprived area of any school in Edinburgh. It also welcomes a high number of pupils from the least deprived areas. Broughton High School has always provided period products should pupils be 'caught short' but now has the resources to provide free period products for more general needs and to encourage pupils to stock-up for holidays. Following an initiative in the school to create awareness of the Scottish Government policy, pupils are coming forward in increasing numbers to pick up what they need.

Pupils were consulted to gather ideas and opinions on how access to free period products could be rolled out effectively. This allowed the school to:

- Develop ways to distribute period products that reflect pupils' views and experience.

- Involve pupils in conversation around stigma and distribution of products.

- Organise the distribution of products at the end of term so pupils had holiday supplies.

- Produce an article to be published in school newsletter to raise awareness of the initiative throughout the wider school community.

A 'pick and mix' event was organised at the end of term where young people could select period products to take home with them. The 'pick and mix' event was utilised by 70 young people. Several other actions have been undertaken to improve understanding of need, distribute period products before school holidays and raise awareness in relation to the availability of free periods, including:

- A survey on reusable period in which 70% of pupils indicated that they would be interested in using reusable products due to environmental concerns;

- The development of the school website in relation to the initiative.

- Delivery of products to all-female PE classes before the end of term.

- Making products available in departments throughout the school.

- A messy play workshop looking at the absorbency of the products.

A pupil steering group was being formed to take this initiative forward in the longer term, including providing whole school assemblies on menstruation from September 2019.

Case study three: Dundee City

Dundee City council adopted a collaborative approach to providing access to free sanitary products, working to design a consistent model that was rolled out across local schools.

Service design

To deliver access to free period products in Dundee City, a working group was formed. The working group comprised education staff, deputy head teachers, guidance teachers and support staff from three schools ( Braeview Academy, St Paul's RC Academy and Harris Academy). The ideas generated by the working group were tried and tested within these school settings.

The approach developed was two-fold:

- Pupils could collect products from identified drop in points like PE, 'guidance departments' or 'pupil support areas'.

- Pupils could pre-order a monthly supply for collection to account for regular need and ensure holiday cover.

Consultation with pupils was undertaken at each school to identify pupils' preferred period products and ascertain where was best to pick up monthly supplies. Each school decided its own pick up points. The timing of collections was also discussed with all schools attempting to make pick up as accessible and discreet as possible. Consultation with the pupils meant that the pupils adapted the model that had been developed to best suit their own needs and environment. As a result of the hard work of this working group this model was rolled out to other schools and adapted. The group was also nominated for an award at the 'Dundee City Council – 2019 Outstanding Service & Commitment Awards' for their efforts.

Learning and feedback

Since the launch of the Scottish Government policy, both staff and pupils at the schools describe the beginning of culture change for everyone involved. There has been more opportunity for learning about periods across a large cross section of people. Council Elected Members, Children and Families Senior Management Team, Head Teachers, Teachers and pupils have been prompted to have conversations around menstruation.

Pupils described the impact of this learning below:

- "We haven't talked about periods much before at school and when we had assemblies about free sanitary products and about how to order the products we needed we left quite excited about it and excited about trying new products like moon cups" (Pupil, S5)

- "It is important for boys to learn about periods too. It is about respect. There was a girl who had a problem with her period, some of the boys were laughing but another one gave her his hoodie and went with her to guidance to help. Boys understand more since we have had free period products in school, we have had assemblies for boys as well as girls to talk about periods. The more boys understand the more respectful they will be" (Pupil, S2)

Pupils also describe the initiative as something that helps keep young people in the classroom:

- "Girls can see the sign in the toilets and stuff and they know where to get the things they need. Now they don't miss classes to go to guidance and they are more confident because it is not something they have to worry about" (Pupil, S2)

Colleges and Universities

Monitoring data

Quantitative monitoring data on spend and numbers of products purchased was received from:

- 25 colleges and 19 universities covering the period 1 September 2018 to 1 February 2019 and;

- 26 colleges and 19 universities covering the period 2 February to 31 August 2019.

Qualitative data on approaches to delivery was received from:

- 26 colleges and 19 universities for the period 1 September 2018 to 1 February 2019 and;

- 15 colleges and 14 universities covering the period 2 February to 31 August 2019.

Where possible, for the colleges and universities where data was not received for the period 1 September 2018 to 1 February 2019, data received for the period 1 September 2018 to 1 February 2019 has been used to provide a more complete overview of delivery. Where this approach has been taken, this is highlighted in-text.

How was access to period products being delivered in colleges and universities?

All 26 colleges and 18 out of 19 universities were making period products available to students on campus. The one remaining university was providing a non-means tested grant (£35 per year) to students, reflecting the sole provision of distance-learning at this institution.

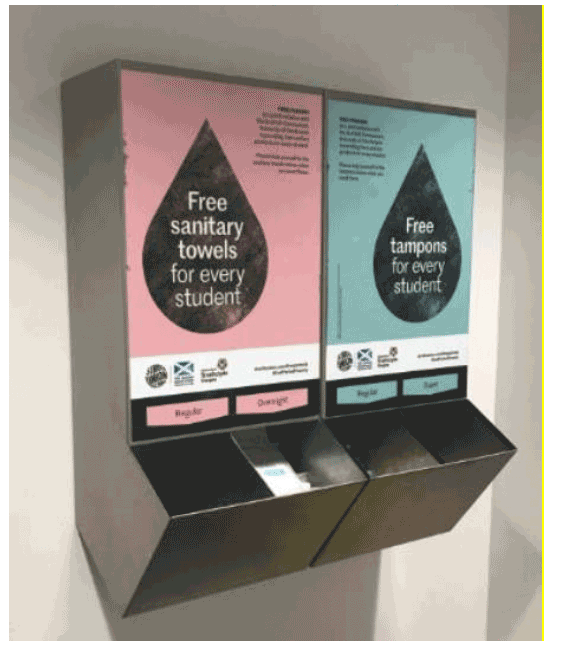

Among the colleges and universities providing access to period products on campus, the majority were providing period products in storage containers/baskets in toilets (65% colleges and 95% of universities), with the provision of products via free vending machines/dispensers implemented by half of all colleges (50%) and via pick-up points by over half of universities (58%). A summary of the delivery models implemented by colleges and universities is provided in Table 5.

All colleges and universities reported at least one delivery model; there was a median of one delivery model implemented by colleges and two delivery models implemented by universities.

| Colleges | Universities | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number | Percentage | Number | Percentage | |

| Storage containers/baskets in toilets | 17 | 65% | 18 | 95% |

| Pick-up points | 8 | 31% | 11 | 58% |

| Pre-prepared packs | 3 | 12% | 6 | 32% |

| Free vending machines/dispensers in toilets | 14 | 50% | 4 | 21% |

| Online ordering | 0 | 0% | 4 | 21% |

| Monetary grants paid to students | 0 | 0% | 1 | 5% |

| Not known | 0 | 0% | 1 | 5% |

Three institutions reported early changes to their delivery model (between 1 September 2018 and 1 February 2019):

- One university reported that they initially piloted an online order form but received low uptake so they switched to placing products in various locations on campus.

- One college reported that they were originally making free period products available in student toilets but changed their delivery model to pick-up points due to misuse of products.

- One university reported that their original delivery model comprised making period products freely available in baskets in a wide range of accessible and gender-neutral toilets across different buildings and campuses. However, due to the size of the campus and the impracticalities this delivery model, it was decided that this model is neither sustainable nor workable as a way of ensuring (i) the availability of products, (ii) access to a larger volume of products at any one time and (iii) the cleanliness and hygiene of the products available. Free vending machines were planned to be installed in Semester 2 in key buildings which were anticipated to be easier to monitor and re-stock.

Did colleges and universities achieve full roll-out of access to free period products and, if not, what are the reasons?

By February 2019, the majority of colleges and all universities had made progress towards providing access to free period products in their institution. Whilst a minority of institutions experienced some delays in the roll-out of provision, the majority of colleges and universities reported that they had achieved full planned roll-out of provision by September 2019. As seen for local authorities, whilst full planned roll-out had been achieved, some colleges and universities reported plans to further expand delivery in various ways, including:

- Encouraging students to take packs of products than individual products.

- Increasin the provision of reusable/environmentally-friendly products.

- Increasing student awareness and uptake of available products.

Are free period products being made available to college and university students outside of term-time?

All colleges and universities reported having arrangements in place to provide access to period products outside of term-time for at least some of the holidays during the 2018-19 academic year.

The most common approaches to providing access to free period products outside of term-term were similar in colleges and universities.

Equal proportions of colleges reported that their institution was open to students outside of term-time (42%) and that they encouraged to "stock up" on products in advance of the holidays (42%). Over two-thirds of universities reported that their institution remained open outside of term-time (68%) and just under half (47%) reported that students were encouraged students to 'stock up' in advance of the holidays. A summary of ways in colleges and universities were making period products to students outside of term-time is presented in Table 6.

| Colleges | Universities | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number | Percentage | Number | Percentage | |

| Institution open during the holidays | 11 | 42% | 13 | 68% |

| Students encouraged to "stock up" in advance of the holidays | 11 | 42% | 9 | 47% |

| Pre-prepared packs or bags of products | 7 | 27% | 8 | 42% |

| Online ordering | 0 | 0% | 4 | 21% |

| Monetary grants paid to students | 0 | 0% | 2 | 11% |

| Other | 0 | 0% | 0 | 0% |

| Not known (no response) | 7 | 26% | 0 | 0% |

Were there any promotional activities to encourage uptake of free period products among college and university students?

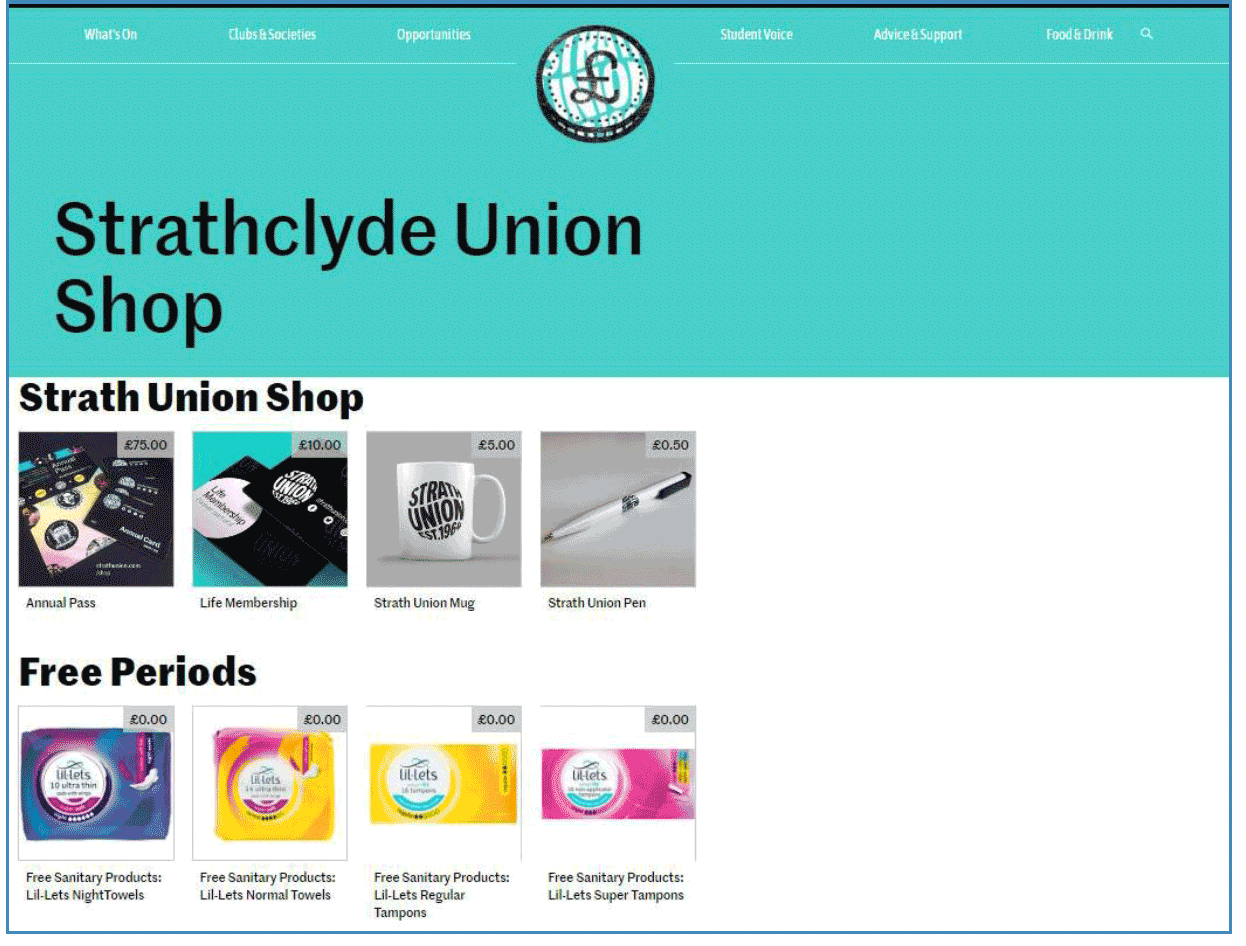

The majority of colleges and universities reported undertaking some promotional activities to encourage students to take free period products. Reported promotional activities included:

- Printed promotional materials distributed on campus, including leaflets, flyers, pop-up displays and posters.

- Digital promotion on campus, including through media screens and 'silent TV ads'.

- Online promotion via social media campaigns and communications, and promotion on Student Association/Union websites.

- Dedicated online and in-person events focussed on period dignity, health and wellbeing, and reusable period products.

- Promotion at general student events, including stands and information stalls 5t 'Freshers' events.

- Direct communication with students through bulletin emails, student newsletters, class rep meetings, the student handbook and student intranet.

What types of period products were purchased and distributed to college and university students?

The majority of colleges and universities providing period products on campus were making a variety of product types absorbencies available to students, including day/night products and applicator and non-applicator tampons.

Among the 24 colleges and 18 universities providing period products on campus, all were providing at least one type of sanitary towel and at least one type of tampon.

Nine colleges and ten universities were making reusable products available, comprising six colleges and five universities making menstrual cups available, and three colleges and five universities making both menstrual cups and reusable pads available.

One university reported making "starter packs" available, comprising a variety of sanitary and non-sanitary products.

How many period products were purchased by colleges and universities?

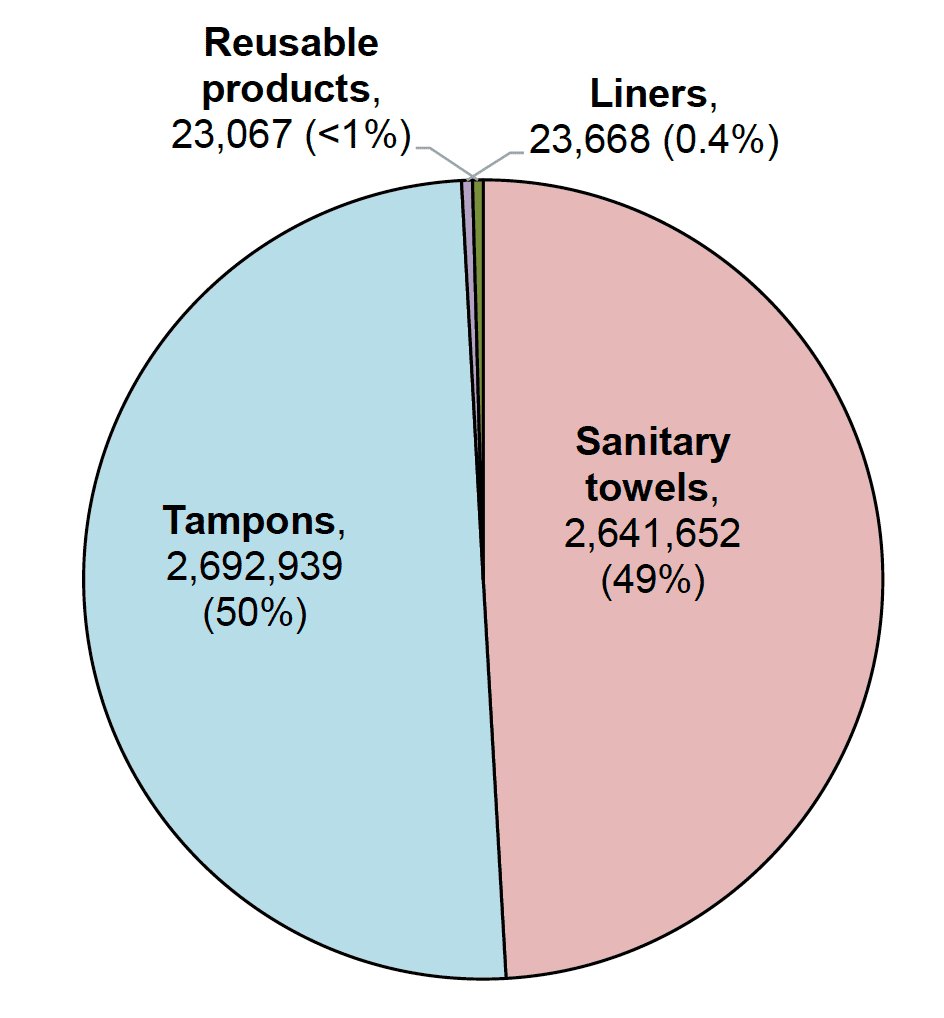

Based on data provided by 23 colleges and 18 universities, at least 5,334,591 disposable period products were purchased during the 2018-19 academic year for distribution in colleges and universities. In addition, at least 23,067 reusable products were purchased by colleges and universities, comprising 15,077 menstrual cups and 7,990 reusable pads. Figure 6 presents a breakdown of the product types purchased by colleges and universities.

Colleges purchased 1,346,931 disposable period products, comprising 713,511 sanitary towels (53%) and 633,420 tampons (47%). This reflects an median of 12 disposable period products per female college student, with half of colleges purchasing between 6 and 18 products per female college student.

Universities purchased 3,987,660 disposable period products, comprising 2,008,232 sanitary towels (50%) and 1,979,428 tampons (50%). This reflects an median of 31 disposable period products per female university student, with half of universities purchasing between 11 and 39 products per female university student.

In addition to period products, a total of 155 grants to the value of £35 were provided by one university to support distance learners to purchase period products.

What is the uptake of period products in colleges and universities?

College and universities were asked to report an estimate uptake rate of period products in their institution during the 2018-19 academic year. Although around half of all institutions provided an estimate, as for local authorities, there was considerable variability in how this figure had been calculated. Following the approach set out above for local authorities, an estimate of uptake was calculated by Scottish Government analysts for each institution based on the reported number of disposable period products purchased during the 2018-19 academic year.[40]

Table 7 summarises the estimated uptake rates in colleges and universities, as defined as the proportion of female students in these institutions accessing free period products to meet their full annual product requirement. These estimated uptake levels are lower than the originally anticipated 35% of pupils accessing period products from their schools to meet their full annual product requirement, on which funding to colleges and universities in 2018/19 and 2019/20.[41]

| Lower quartile | Median | Upper quartile | |

|---|---|---|---|

| (25% of unit prices are lower than this value) | (middle value) | (75% of unit prices are lower than this value) | |

| Colleges | 2% | 4% | 6% |

| Universities | 4% | 10% | 13% |

As for local authorities, it is important to highlight that these figures reflect an estimate only and interpretation of these figures require a number of assumptions, including that all disposable period products purchased by colleges and universities were distributed and taken by students. In addition, in line with assumptions made in the calculation of funding allocations, uptake is defined as the proportion of students taking their full annual proportion requirement. In reality, the pattern of usage is likely to reflect a larger proportion of pupils taking a smaller proportion of their annual requirement (see findings of the student survey discussed later).

Some colleges and universities reported that promotion had had a positive impact on uptake. For example:

- "on-line and local events were held at each campus. It did increase the uptake and interest in all the resources…especially the sustainable ones." (University)

- "Poster campaign to advertise free products available at the beginning. Student Representative Council (SRC) promotions during Freshers week. Freshers week had a positive impact on uptake of re-usable products." (University)

- "In our College main reception area we have a pop up area which is used for a variety of promotions. At periodic points this area will utilised to promote the scheme and specifically the use of reusable products. These face to face initiatives led to the biggest uptake of reusable products." (College)

However, the some colleges felt that promotion had not had an impact on uptake:

- "We have included Sanitary products at all Health and Wellbeing related events we have held and placed them on the stalls. This didn't have a large impact as the current provision is in key areas for uptake already."

- "Messages were distributed to all students, predominantly prior to holidays and other times when individuals were out of college. These messages did not appear to have an impact on uptake and for 19/20 and beyond, a more sustained promotional campaign will be conducted throughout the academic year - supported by Student Association volunteers."

How were colleges and universities purchasing period products?

Limited data is available on the purchasing models implemented by colleges. However, based on available data from 14 colleges, the most commonly reported approaches were to purchase products on an ad hoc basis based on demand (27%) and to purchase products in bulk at the start of each term/points in the year.

Similarly, half of universities reported purchasing products on an ad hoc basis dependent on demand (50%), and over a third reporting purchasing products in bulk at the start of the academic year (39%). Table 8 provides a summary of purchasing approaches reported colleges and universities.

| Colleges | Universities | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number | Percentage | Number | Percentage | |

| Products purchased in bulk at the start of the academic year | 3 | 12% | 7 | 39% |

| Products purchased in bulk at the start of each term/points in the year | 6 | 23% | 5 | 28% |

| Products purchased on an ad hoc basis depending on demand | 7 | 27% | 9 | 50% |

| Not known (no response) | 12 | 46% | 4 | 22% |

| Other | 0 | 0% | 0 | 0% |

What was the unit price of period products purchased by colleges and universities?

The median unit price (middle unit price) was 11.9p per disposable period product[42] purchased by colleges and universities; the unit prices for tampons and sanitary towels were similar. As shown in Table 5, there a substantial range of unit prices. Among the colleges and universities who purchased reusable period products, there was a median unit price of £5.83 for menstrual cups and £2.50 for reusable pads. Note that there was little variability in the unit price of products purchased by colleges versus universities.

| Lower quartile | Median | Upper quartile | |

|---|---|---|---|

| (25% of unit prices are lower than this value) | (middle value) | (75% of unit prices are lower than this value) | |

| Sanitary towels | 8.9p | 11.9p | 16.8p |

| Tampons | 9.8p | 12.0p | 20.1p |

| Menstrual cups | £3.59 | £5.83 | £14.10 |

| Reusable pads | £2.45 | £2.50 | £7.63 |

| Liners | 3.9p | 4.0p | 4.2p |

What did colleges and universities spend purchasing period products for distribution in schools?

The total reported spend on period products across all colleges and universities was £1,006,028 (net VAT), comprising £307,988 among colleges and £698,040 among universities. Just under half of reported spend on period products (47%; £471,453) was incurred between 1 September 2018 and 1 February 2019 and just over half (53%; £534,575) was reported to have occurred between 2 February and 31 August 2019.

To understand the scale of spend on period products during the 2018-19 academic year, spend was compared against the funding distributed to colleges and universities to support the purchase of period products. The total funding allocation for colleges and universities to support the purchase of period products for distribution in schools between 1 August 2018 to 31 March 2020 was £5.1 million[43], comprising £2.1 million for colleges and £2.9 million for universities.

As the 2018-19 academic year does not cover the whole of this period, a proportion has been calculated to approximate anticipated spend at September 2019 assuming full spend of the 2019/20 funding allocation by end of March 2020. Assuming a constant rate of spend on period products throughout the financial year, spend on period products across the sector in the region of £3.3 million would be anticipated by 1 September 2019.[44]

Based on data from all 26 colleges and 19 universities, reported spend on period products during the 2018-19 academic year reflects 50% of the 2018/19 product funding allocation, reducing to 30% when compared against the anticipated spend of £3.3 million by 1 September 2019.

Table 6 presents a breakdown for colleges and universities separately.

| Colleges | Universities | |

|---|---|---|

| Spend on period products | £307,988 | £698,040 |

| Percentage of 2018/19 allocation spent | 36% | 60% |

| Percentage of anticipated spend by 1 September 2019 | 22% | 37% |

What did college and universities spend on development and administration?

Based on data from all 26 colleges and 19 universities, the total spend on development and administration across all colleges and universities was £518,374 (net VAT), comprising £338,854 among colleges and £179,520 among universities.

Additional spend gross VAT (20%) is presented in Footnote [45].

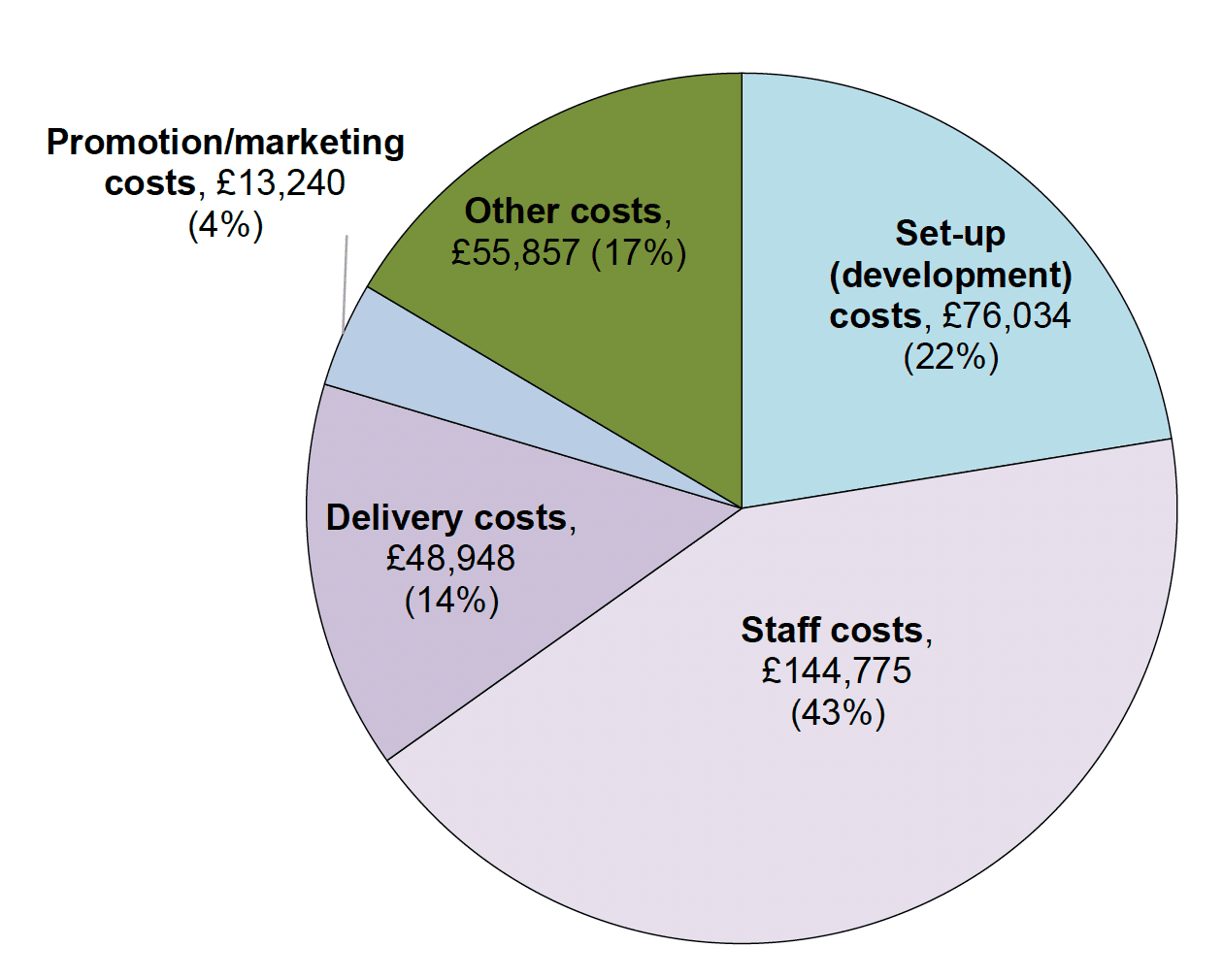

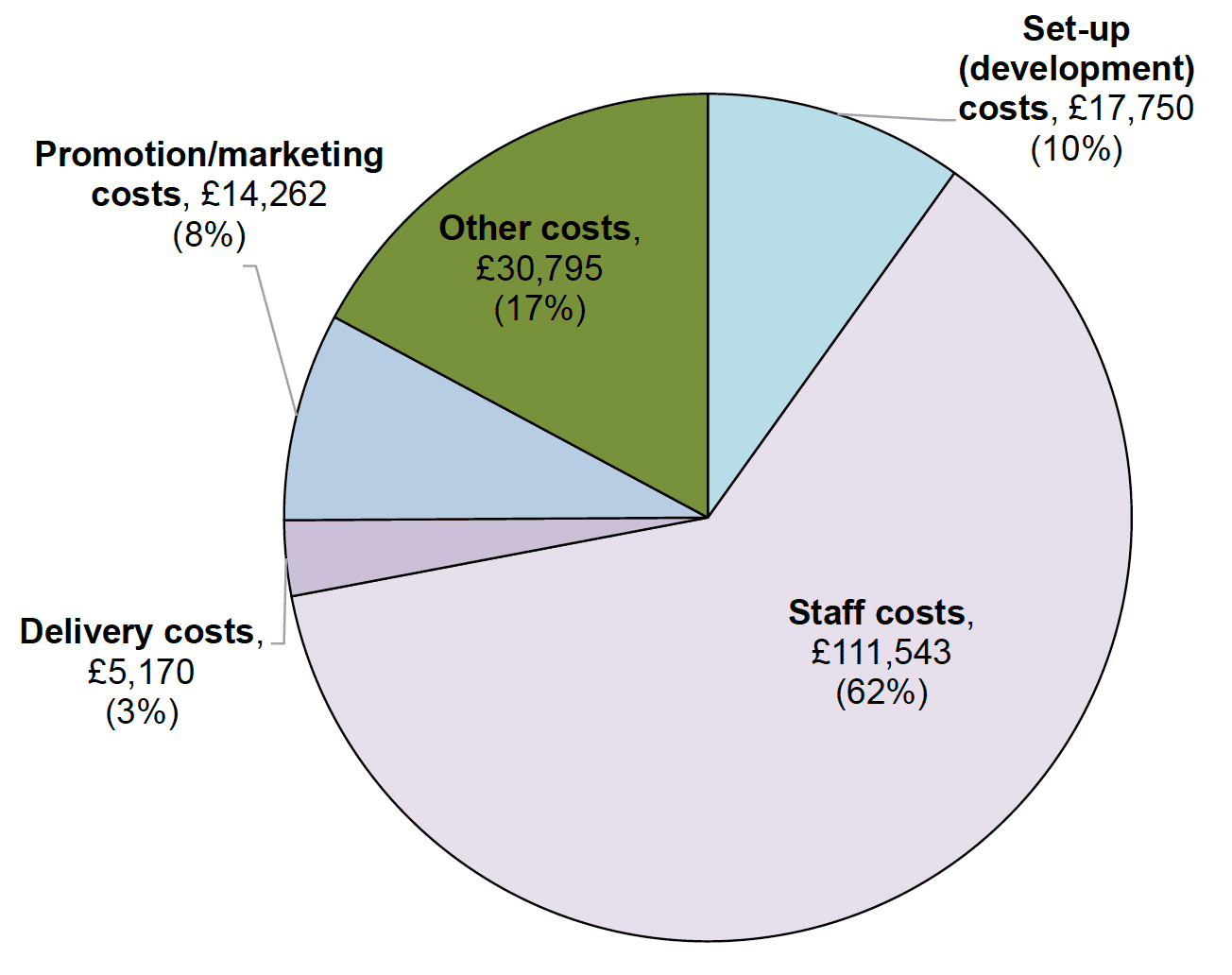

Figure 7 provides a breakdown of spend on development and adminstation by colleges. As shown, staff costs comprised almost half (43%) of all the development and administrative spend incurred by colleges during the 2018-19 academic year, with just under a quarter (22%) spent on set-up of the provision.

Figure 8 provides a breakdown of spend on development and administration by universities. As shown, and consistent with the breakdown for colleagues, staff costs comprised the greatest proportion of all development and administrative spend, with universities spending just under two-thirds (62%) on staff costs. The proportion of spend on set-up (development) by universities was lower than for colleges at 10%.

What worked well in colleges' and universities' delivery?

Colleges and universities were asked to report what they felt had worked well in their chosen delivery model. Fourteen colleges and 15 universities provided a response. This revealed two key themes:

Ease of access to products:

- "We have adopted a multi-delivery model to reach all students – self-serve machines, baskets, pick up points, emergency food parcels – and will continue to do so as this model is working for us. The machines and baskets are re-stocked regularly and students are very forthcoming in letting us know if they need products. This is a huge culture shift, in such a short period.

- "Capacity to set up supply points in over 60 locations due to model being used: University Cleaning Services staff monitor supplies and re-order where necessary- this has worked well."

- "Accessibility of products with the tokens in the toilets for individuals to take – this part of the scheme was implemented latterly as we awaited new machines. Prior to that students had to pick up tokens for our Student Support Centre or reception the products are widely available in toilets with no barriers to access and each basket of product is displayed with a notice that promotes use and explains why the products are available."

- "Having a combination approach of vending machine/hand-out/re-useable/holiday packs continues to be a model that is working well for students and staff. Positive feedback suggests that vending machines continues to be the easiest and most accessible method for students and staff to access products."

- "The choice to make products free to vend in all toilets ensured that all students / college users can take advantage of the provision without having to approach members of staff. The model is felt to have positively impacted the uptake."

Providing dignified access, including privacy and anonymity:

- "Products are placed in toilets and restocked on a regular basis. This means students can take them anonymously."

- "The routes available for students to access sanitary products allow them the privacy if required as well as trying to remove the taboo by also having products in various location around the campus for students to help themselves to holiday pack."

What worked less well in colleges' and universities' delivery?

Colleges and universities were asked to report what they felt had worked less well in delivery. 11 colleges and 13 universities provided a response. This revealed two key themes:

Limited choice of products available:

- "The toilet dispensers have not been as popular. I believe this is because there is restriction to the variety of products available." (College)

- "Vending machine products may limit the choice that is available to students and staff. We plan to review the vending machine products in 2019-2020 in terms of quality and to explore opportunities of providing additional products." (College)

Barriers to accessing products:

- "Student advisers are exceptionally busy and often working 1:1 with individuals, requiring privacy. Students may have been reluctant to wait, or interrupt a private meeting in order to request hygiene packs when in dire straits or packs of product for holidays" (College)

- "We offer full boxes of products in a self-service 'shop front' situation. We have heard that some students have felt anxious accessing public locations so this is another reason why we will place collection units within toilet spaces. Starting with one location per campus has enabled us to investigate usage so that we can evaluate the time spent administering and managing the scheme on campus." (University)

How burdensome was it for colleges and universities to administer the access to free period products scheme?

There was a mixed response from colleges and universities on the extent to which the provision of free period products to their students had been burdensome. As seen for local authorities, among those that reported some burden, most reported that this had reduced as the scheme has become more established. This is illustrated in the following quotes:

- "Initially very. We don't have a lot of slack in the system for holding stock or moving it around to where it needs to be. We've improved as we've gone on and as experience shows which areas are high/low use." (University)

- "There was some burden in the initial set up of the scheme but it is not too burdensome to administer now." (University)

- "The access to sanitary products scheme took planning and time to develop the roll out; however, once in place the scheme has worked well." (College)

- "A little time consuming to get up and running but once in place it appears to be working well." (College)

Some institutions noted that whilst the delivery of the access to free period products scheme had placed some burden, they felt it worthwhile:

- "The expectation is significant and placed on teams that already have an incredible array of duties to complete. But the burden is completely justified by the benefit that the funding provides to our student community." (University)

- "The scheme has taken quite a bit of time to administer, for full time staff with an already full time remit. Fortunately, there is positive buy in, in driving this forward for the betterment of the student experience." (College)

Were there any logistical/operational challenges faced by colleges and universities in distributing products?

A minority of colleges and universities reported experiencing some logistical or operational challenges in distributing products. The vast majority of challenges reported concerned ensuring that supplies of period products were sufficiently stocked, as illustrated by these quotes:

- "It is proving challenging re-stocking the machines and baskets fast enough, especially after the morning and lunch breaks." (College)

- "Yes, a lack of Portering/Cleaning staff to distribute the products quickly enough made it difficult to meet demand at times." (University)

- "Ensuring sanitary provision was kept sufficiently topped up through the working day and that there were staff available to do that" (University)

One college and one university reported experiencing challenges around the misuse of available period products:

- "Our Facilities team expressed concern at mis-use of products ie littering and blocked toilets." (College)

- "Some students used some products to decorate one of the male toilets." (University)

2.1.1. Case studies

This section presents a selection of case studies produced by SFC, in collaboration with colleges and universities. The purpose of these case studies is provide examples of the approaches to access and promotion taken by institutions during the 2018-19 academic year, and to provide colleges and universities with the opportunity to share additional detail on the development of the policy within their institution and the rationale for the approach taken.

Meeting the needs of remote and distance learners

The Open University in Scotland

The Open University (OU) is a distance learning provider with no campus in Scotland. The OU in Scotland had 17,076 students in the 2018-19 academic year, 63% of whom were women. The majority (72%) of new undergraduates were on low incomes and in receipt of the part-time fee grant administered by the Student Awards Agency for Scotland (SAAS). The unique model of supported distance learning at the OU presented a challenge for the delivery of free period products, and required the OU to develop an innovative approach. Consideration was given to a range of potential approaches:

- Sending products by post to its students: the costs were found to be prohibitive.

- Sending vouchers to students who requested them: 21.8% of new OU undergraduates live in remote and rural areas of Scotland, and 22.8% have a declared disability so the accessibility of any given provider would be a challenge.

- On-demand service: the costs of the products, warehousing, postage and the administration costs were found to be prohibitive.

The delivery model chosen to most effectively meet student need was to provide a grant of £35 each year, including holidays. Students contacted the OU to access this grant, and their eligibility was checked (i.e. that they are currently registered on a module and domiciled in Scotland). The OU did not ask for the student's gender to ensure a fully inclusive approach. The finance team then issued a cheque by post. The OU had no control over whether the money was used for its intended purpose but checked that a student has not applied for a grant more than once in a year.