Procurement activity: annual report 2021 to 2022

An overview of public procurement activity in Scotland for 2021 to 2022, based on information contained in individual annual procurement reports prepared by public bodies and other relevant information.

2. Overview of procurement activity

2.1 Summary of procurement activity

The use of the Public Contracts Scotland (PCS) portal is mandatory for all public contracts that are regulated by the 2014 Act. While public bodies are not required to use PCS to advertise contracts that fall below the thresholds set out in the Act, many still do so. In 2021 to 2022, there were 5,682 new registrations to the PCS website of new users, which include buyers and supplier users and organisations. In terms of the numbers of contracts advertised on the portal, according to the PCS usage report for 2021 to 2022, during the year, a total of 15,634 new public sector business opportunities were advertised. Of these, 14,351 (92%) were for low value contracts and, more specifically, 12,275 (79%) were for Quick Quotes. Moreover, some 18,880 suppliers were awarded public sector contracts through PCS. Of these suppliers, 78% were Small and Medium-sized Enterprises (SMEs), 74% were Scottish-based, and 62% were Scottish-based SMEs.

6,359

6,359 regulated contracts were awarded by the 128 reporting bodies during the reporting period.

The annual procurement reports give further insight into levels of contracting activity in relation to the number of regulated contracts awarded during the year. Across 128 public bodies providing the relevant information, a total of 6,359 regulated contracts were awarded during the year. Across 127 public bodies, the total combined value of regulated contracts awarded was £9.3 billion.

The annual procurement reports also provide a wide variety of examples of the types of goods, services and works procured through regulated contracts awarded during the year. The nature of these examples suggest that, during 2021 to 2022, public bodies were continuing to deal with the impact of COVID-19 while also moving towards a ‘new normal’. Examples included, but were not limited to:

- across central government organisations and other significant bodies – telecommunication and conferencing services, HR recruitment services, media services, hybrid events, and IT development and support services;

- within the local government sector – health and social care provision, blended employability services, environment improvement works, the remote processing of revenues and benefits, and wellbeing and counselling services;

- across the health sector – call centre resources for the COVID-19 National Contact Centre, agency locums and nurses, patient transport, drug and alcohol recovery services, and influenza vaccines;

- within the universities and colleges sector – online learning resources, hybrid classrooms, student counselling services, personal protective equipment, mobile client devices, and student accommodation and cleaning;

- across registered social landlords – landscape maintenance, cleaning services, new build housing developments, and lift servicing.

Indeed, NHS National Services Scotland (NHS NSS) commented on their gradual movement towards more business-as-usual procurement activity over the course of the year:

Following the initial emergency response to the Covid-19 pandemic in financial year 2020-21, in the reporting period NSS reverted to more business-as-usual procurement processes with the number of direct awards under extreme urgency (Regulation 33(1)(C) and 33(3)) reducing significantly. As we emerge from the pandemic there is a renewed focus on financial sustainability, the climate emergency and providing solutions that improve the wider health and wellbeing of the people of Scotland.”[3]

Such a high volume of procurement activity was also reflected in significant amounts of procurement spend. The Hub data shows that, during the reporting year, total Scottish public body procurement spend (with suppliers based in Scotland and elsewhere) was £16.0 billion.[4] Total procurement spend with suppliers in Scotland alone was £8.9 billion (56%).

£16.0 billion

Scottish public sector procurement spend totalled £16.0 billion, of which £8.9 billion was spent in Scotland alone.

Local government bodies accounted for most of the procurement spend in Scotland. Indeed, of the £8.9 billion of spend in Scotland, £5.4 billion (60.6%) resulted from local government spend. Central government bodies accounted for £2.1 billion (or 23.4%) of spend in Scotland.

When compared with the data for the previous two reporting years, Figure 1 shows that broadly, patterns of procurement spend within different parts of the public sector remain relatively stable. The last report (covering 2020 to 2021) highlighted the sharp increase in the proportion of spend within central government which resulted at least partly from the sector’s efforts in coordinating the response to the COVID-19 pandemic. That the proportion of spend within this sector has since decreased from 29.3% to 23.4% indicates a return to ‘business as usual’ as the Scottish public sector continued to emerge from the pandemic.

2.2 Good for the economy

The 2023 to 2028 Public procurement strategy for Scotland sets out the vision and ambition for public procurement in Scotland in respect to wider policy objectives. In anticipation of the Strategy coming into full effect through 2024, the following sections are defined under the Strategy’s four main objectives. The vision statement of the strategy is “putting public procurement at the heart of a sustainable economy to maximise value for the people of Scotland.”

The Strategy’s objectives are:

1. Good for Businesses and their Employees

2. Good for Places and Communities

3. Good for Society

4. Open and Connected

Using the latest Scottish Government Input- Output model of the economy, it is estimated that £16.0 billion of procurement spending in 2021 to 2022 supported around £13.8 billion of activity, around 130,000 full-time equivalent jobs and contributed around £7.5 billion to Scottish GDP within the wider domestic economy when taking into account supply chain and re-spending of wage effects. This represents around 5% of the Scottish economy. It should be noted that these effects are estimated using a pre Covid model of the Scottish economy.[5]

2.3 Good for businesses and their employees

The 2023 to 2028 Public procurement strategy for Scotland defines ‘good for businesses and their employees’ as aligning the public sector to maximise the impact of procurement to boost a green, inclusive and wellbeing economy, promoting and enabling innovation in procurement.

2.3.1 SMEs

Over the course of the year, the Scottish public sector continued to do much of its business with SMEs from Scotland, elsewhere in the UK, and further afield. In 2021 to 2022, total Scottish public body procurement spend with SMEs, regardless of location, was £6.4 billion. This amounts to 44.2% of all spend (where business size is known).[6]

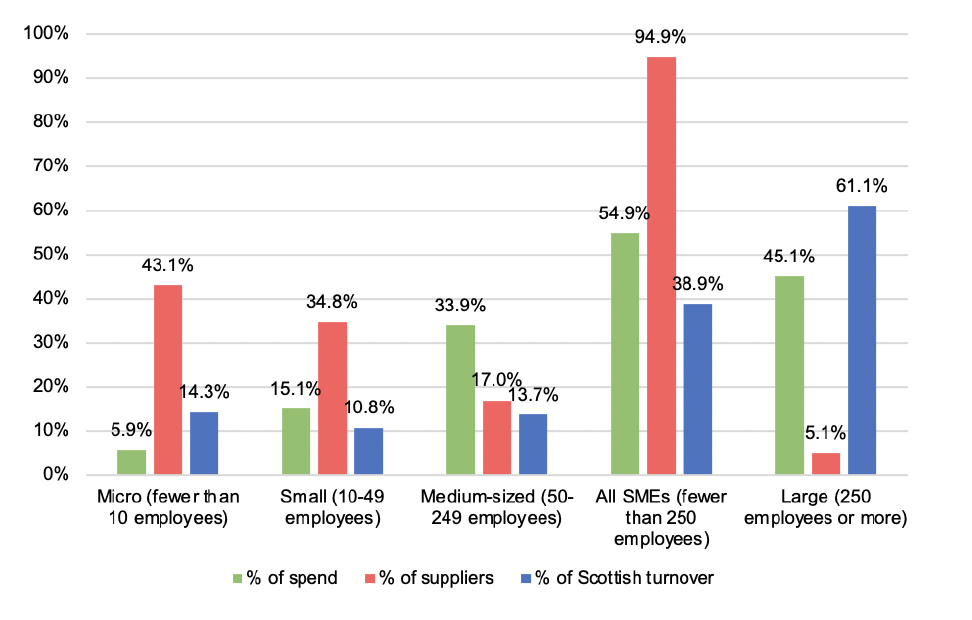

More specifically, when we consider the procurement spend that took place with suppliers based in Scotland, we learn that SMEs accounted for over half (54.9%, or £4.2 billion) of this spend – and this £4.2 billion of spend can be accounted for by some 16,828 SME suppliers. The largest share (£2.6 billion) of SME spend was with medium-sized businesses, followed by small businesses (£1.2 billion) and micro businesses (£449.2 million).

£4.2 billion

SMEs received £4.2 billion (or 54.9%) of procurement spend in Scotland.

Figure 2 provides a full breakdown of the proportions of procurement spend that went to suppliers of different sizes, as well as the numbers of suppliers represented by each size category. It shows that while micro businesses made up the smallest proportion of spend in Scotland (5.9%), these organisations nevertheless represented the largest proportion of suppliers; indeed, 43.1% of all suppliers in receipt of spend in Scotland were micro businesses.

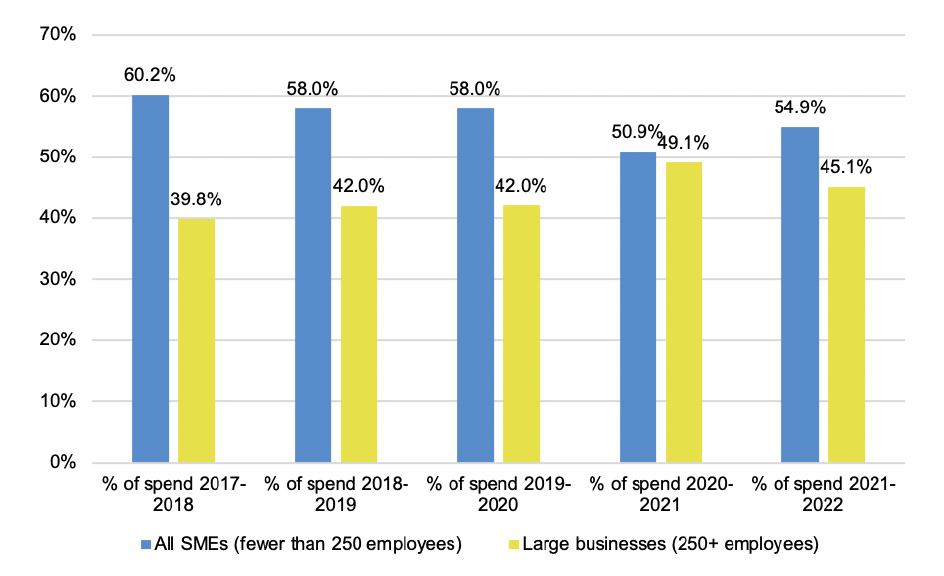

Given the longer-term picture over the last five years, as indicated in Figure 3, the data suggest that levels of procurement spend with SMEs may be gradually returning to pre-pandemic levels. When compared with the figures for 2020 to 2021, as highlighted in the last report, the share of spend with

Scottish-based SMEs increased from 50.9% to 54.9%. Meanwhile, the value of spend with Scottish-based SMEs increased from £3.5 billion to £4.2 billion during the same period.

The Scottish Government recognises the importance of ensuring that businesses of all sizes are able to do business with the public sector, given the significant contribution that both SMEs and larger firms alike make to the Scottish economy. When the procurement spend data is compared with data on turnover (as provided in the Businesses in Scotland data for 2022), we learn that, despite receiving 54.9% of procurement spend in Scotland, SMEs accounted for 38.9% of total Scottish turnover amongst registered private businesses. Conversely, large businesses received 45.1% of procurement spend while accounting for 61.1% of turnover.

Sub-contracting opportunities are an important means by which public bodies can involve SMEs in the delivery of public contracts. Sixty-two public bodies provided information in their annual procurement reports about the value of contracts sub- contracted to SMEs during the year. Across these 62 bodies, the total combined value of contracts sub-contracted to SMEs was £166.2 million.

During the reporting year, the Scottish Government also continued to provide a funding contribution to the Supplier Development Programme (SDP). The SDP provides advice, guidance and training to Scottish-based SMEs and third sector organisations which are interested in contracting with the public sector, through a combination of online and in-person support. The SDP annual report for 2021 to 2022 shows that, during the year, 1,623 new registrations were made to the programme, bringing the total number of registrations to 19,595.

2.3.2 Third sector organisations

Third sector organisations play an important role in supporting local communities and also in stimulating local economic growth. For the purposes of this report, the third sector includes charities, social enterprises and voluntary groups.

In preparing this report, significant work was undertaken to gain an accurate understanding of how much the Scottish public sector spends with third sector organisations through its procurement activity each year.

By linking the list of suppliers in receipt of procurement spend (as noted in the Hub data) with data on all of the known social enterprises in Scotland (gathered as part of the Social Enterprise Census), and by also drawing on information on the Hub about the registered charity status of individual suppliers in receipt of spend, it was possible to establish how much Scottish public bodies spent with social enterprises and, separately, with registered charities during the reporting year. These two figures were then combined to establish a figure for total spend with the third sector during the reporting year.

As a result of this exercise, it is estimated that, during 2021 to 2022, the Scottish public sector spent around £1.1 billion with third sector organisations in Scotland. This equates to around 12.5% of all Scottish public body procurement spend in Scotland and is an increase from the £944 million spent last year.

£1.1 billion

Third sector organisations received £1.1 billion (or 12.5% of public procurement spend) during the reporting year.

It is important to note that the third sector is not limited to charities and social enterprises; it also includes voluntary groups and, at present, the Hub does not verify whether a supplier in receipt of procurement spend is a voluntary group. It is also likely that there are some social enterprises operating in Scotland that are yet to be identified by – and included in – the Social Enterprise Census.

As such, the above figure is presented as an estimate. Indeed, the real level of spend with the third sector is likely to be greater than the figure quoted.

Public bodies also continued to use their annual procurement reports as a means of demonstrating the steps taken to involve third sector organisations in their procurement activity during the year. The following example, taken from the City of Edinburgh Council’s annual procurement report, shows how the Council engaged with third sector organisations:

”In addition to contracting activity, the Council continued to engage with suppliers and stakeholders through virtual meetings and events, including presenting and facilitating at the national Meet the Buyer event where the Commercial and Procurement Services (CPS) team engaged with over 160 suppliers in one day, presenting at the Edinburgh Social Enterprise (ESE) Climate Action Fringe, providing an open invitation to engage directly with CPS each month and publishing a quarterly supplier newsletter on the Council website.”[7]

2.3.3 Supported businesses

Supported businesses are defined as organisations whose main aim is to integrate disabled or disadvantaged people, both socially and professionally, and whose workforce comprises at least 30% disabled or disadvantaged people.

The Scottish public sector continues to engage with supported businesses through its contracting activity. The analysis of annual procurement reports shows that, across the 113 public bodies providing the relevant information, a total of 35 regulated contracts were awarded to supported businesses during the reporting year; moreover, across 110 public bodies, the total combined spend on regulated contracts awarded to supported businesses was £27.9 million, a significant increase from the £13.3 million awarded a year before.

£27.9 million

Across 110 public bodies, £27.9 million in regulated contracted was awarded to supported businesses.

Taken from the University of Strathclyde’s annual procurement report, the following example highlights the importance of the Scottish Government’s framework agreement for supported businesses in enabling these organisations to engage in public contracts:

”University Procurement utilised the Scottish Government’s Framework Agreement for supported factories and businesses for the replacement of 1,300 mattresses and bedframes across our student residences. The total value of this contract is in the region of £437,000 over the duration of the contract. The contract with Dovetail continues to deliver high quality products to the University whilst supporting the achievement of Dovetail’s goals of providing more meaningful employment for disabled and disadvantaged members of the community.”[8]

2.3.4 Spend in Scotland by supplier business sector

Each year, the Scottish Government carries out an analysis of Scottish public body procurement spend in Scotland, broken down by the business sectors of the suppliers in receipt of procurement spend. This year, steps were taken to re-classify the sectoral spend data in line with the Standard Industrial Classification, replacing the vCode classification that was used in previous years of the analysis.[9] This was done to align the spend data with other datasets which use the same classification – for example, the Businesses in Scotland dataset – thus enabling the spend data to be interrogated further.

Table 1 provides a full breakdown of total Scottish public body procurement spend in Scotland by supplier business sector (where supplier sector is known and could be matched with the Standard Industrial Classification). It shows that the largest share of spend (£2.1 billion, or 23.4% of spend) was with suppliers operating in the construction sector, followed by the human health and social work activities sector (£1.9 billion, 21.7%). Suppliers in the transportation and storage (£1.3 billion, 14.6%) and administrative and support service activities (£951.5 million, 10.7%) sectors also received relatively high shares of procurement spend.

| Business sector | Value of spend | % of spend |

|---|---|---|

| Accommodation and food service activities | £88,011,511 | 1.0% |

| Administrative and support service activities | £951,451,564 | 10.7% |

| Agriculture, forestry and fishing | £50,410,240 | 0.6% |

| Arts, entertainment and recreation | £96,510,771 | 1.1% |

| Construction | £2,067,334,975 | 23.4% |

| Education | £114,701,382 | 1.3% |

| Electricity, gas, steam and air conditioning supply | £55,353,017 | 0.6% |

| Financial and insurance activities | £112,534,698 | 1.3% |

| Human health and social work activities | £1,919,395,251 | 21.7% |

| Information and communication | £123,921,609 | 1.4% |

| Manufacturing | £166,056,572 | 1.9% |

| Mining and quarrying | £85,142,481 | 1.0% |

| Other service activities | £24,548,565 | 0.3% |

| Professional, scientific and technical activities | £728,851,046 | 8.2% |

| Public administration and defence; compulsory social security | £45,439,455 | 0.5% |

| Real estate activities | £83,596,252 | 0.9% |

| Transportation and storage | £1,292,322,492 | 14.6% |

| Water supply; sewerage, waste management and remediation activities | £231,466,910 | 2.6% |

| Wholesale and retail trade; repair of motor vehicles and motorcycles | £615,670,121 | 7.0% |

| Total | £8,852,718,912 | 100.0% |

Earlier in this report, it was said that in 2021 to 2022, SMEs accounted for over half (54.9%, or £4.2 billion) of all Scottish public body procurement spend in Scotland. Although this is welcome, the Scottish Government always seeks to do more to create a level playing field for SMEs when it comes to participating in public sector contracts.[10] When we combine the sectoral spend data with wider SME data from the Businesses in Scotland dataset, we can gain an insight into the extent to which SMEs can be found in sectors where procurement spend is concentrated. This, in turn, enables us to pinpoint sectors where actions and initiatives around SME access should be targeted.

Figure 4 provides an overview of the proportions of all Scottish public body procurement spend in Scotland that went to suppliers operating in each sector. This information is directly compared with data on the proportions of the total number of SMEs in Scotland that can be accounted for by each sector, as indicated in the Businesses in Scotland data.[11]

The chart presents a mixed picture as to whether SMEs are found in sectors where most procurement spend takes place. Indeed, it is clear that while SMEs are more prevalent in some sectors than in others, they can be found in all sectors of the economy. This includes areas of relatively high procurement spend, as well as areas of relatively low spend. On a practical level, this means that efforts designed to encourage SME participation in public procurement should be cognisant of the rich diversity that exists within the Scottish SME landscape.

For example, the chart shows that in 2021 to 2022, the construction sector accounted for 23.4% of Scottish public body procurement spend in Scotland, while also accounting for a relatively large proportion of all SMEs in Scotland (12.6%). However, other high- spend areas such as human health and social work activities (which received 21.7% of procurement spend) and transportation and storage (14.6% of spend) accounted for relatively small shares of all SMEs (3.9% and 4.0% respectively). The largest proportions of SMEs were found in the professional, scientific and technical activities (15.2%) and wholesale and retail trade/repair of motor vehicles and motorcycles (14.2%) sectors – and these sectors received relatively modest levels of procurement spend (8.2% and 7.0% of spend respectively).

2.3.5 Fair Work First

Procurement is an important means through which public bodies can promote Fair Work practices amongst the suppliers involved in the delivery of essential services.

In the 2021 to 2022 reporting year, 101 public bodies (77% of those providing an annual procurement report for that year) included information in their reports about the number of regulated contracts awarded during the period that contained a scored Fair Work criterion. Amongst these 101 bodies, a combined total of 1,645 regulated contracts containing a scored Fair Work criterion were awarded. This represents 44% of all regulated contracts awarded by these 101 bodies.

Another way that public bodies can use their procurement activity to promote Fair Work practices is by encouraging their suppliers to pay the real Living Wage when delivering public contracts. This can be done, for example, by including payment of the real Living Wage in award criteria, or by mandating it as part of the contract terms and conditions. Indeed, in October 2021, the Scottish Government announced that in order to be considered for most of its own contracts, companies must agree to pay at least the real Living Wage to workers on public contracts where it is deemed a proportionate and relevant requirement and where it does not discriminate against potential bidders.

During the reporting year, 95 public bodies (71% of those providing an annual procurement report) included information about the number of unique suppliers who committed to paying the real Living Wage in the delivery of a regulated contract awarded during the year. Across these 95 bodies, a combined total of 2,016 suppliers committed to paying the real Living Wage in the delivery of regulated contracts.[12]

2,016

Across 95 public bodies, a combined total of 2,016 unique suppliers committed to paying the real Living Wage in delivering regulated contracts.

As an example of how public bodies are promoting Fair Work First in their procurement activity, the following extract was taken from the Advanced Procurement for Universities & College’s (APUC) annual procurement report:

”Where relevant and proportionate, APUC considers the fair work practices of suppliers in its procurements, including the application of the Living Wage through its Framework Agreement tender process. APUC has standardised wording for its tender questions on fair work practices in line with Scottish Government guidance.

APUC reports spend with living wage suppliers. This can be drawn from supplier MI and from Hunter. APUC capture Living Wage status as part of its Supply Chain Contract Management process … and promote this functionality to the sector for institutions to embed a similar process.”[13]

2.3.6 Prompt payment

The Scottish Government recognises the importance of ensuring that those who supply goods, works and services to the public sector are paid on time. The timely payment of businesses and organisations across the supply chain is key in ensuring the continued viability of Scotland’s supplier base and, in turn, the ongoing delivery of everyday, essential public services. While prompt payment has been a key focus for Scottish public procurement for a number of years, the issue was particularly crucial during the 2021 to 2022 reporting year, as public bodies and their suppliers gradually emerged from the COVID-19 pandemic and transitioned into a phase of economic recovery.

The annual procurement reports provide an insight into public bodies’ performance in relation to supplier prompt payment during the year 2021 to 2022. Ninety-nine public bodies (75%) provided analysable data on the percentage of invoices paid on time.[14] Amongst these 99 bodies, the average percentage of invoices paid on time was 86%.

Public bodies can ensure the timely payment of businesses and organisations across the supply chain by including contract terms which require the prompt payment of invoices. Ninety-six public bodies (73% of those submitting an annual procurement report for the year) provided data on the number of regulated contracts awarded during 2021 to 2022 which contained a contract term requiring the prompt payment of invoices in public contract supply chains. Across these 96 bodies, 2,978 regulated contracts containing such a contract term were awarded.

2,978

Across 96 public bodies, 2,978 regulated contracts were awarded including contract terms requiring the prompt payment of invoices.

In its own annual procurement report, the Scottish Government sets out how the organisation ensures the prompt payment of suppliers across all tiers of the supply chain through good contract management and through the use of Project Bank Accounts.

”Through our contract management arrangements, we monitor the percentage of our valid invoices paid on time, our average payment performance, any complaints from contractors and subcontractors about late payment and we take action where appropriate.

Recognising the construction sector in particular can suffer from late and extended payment terms from business to business, we required the use of project bank accounts, from which a public body can pay firms in the supply chain directly as well as making payments to the main contractor. Project bank accounts improve cash flow and help businesses stay solvent, particularly smaller firms which can be more vulnerable to the effects of late payments.”[15]

2.4 Good for places and communities

The 2023 to 2028 Public procurement strategy for Scotland defines ‘good for places and communities’ as aligning the public sector to maximise the impact of procurement with strong community engagement and development to deliver social and economic outcomes as a means to drive wellbeing by creating quality employment and skills.

2.4.1 Spend in Scotland by supplier location

Through their procurement activity, Scottish public bodies continue to spend with suppliers in communities across the length and breadth of Scotland.

Figure 5 contains information about the proportions of Scottish public body procurement spend that can be accounted for by suppliers based in each of Scotland’s 32 local authority areas (where local authority is known). It shows that suppliers based in Glasgow City received the largest share (22.5%, or £2.0 billion) of all procurement spend in Scotland. Thereafter, suppliers based in City of Edinburgh received the second- largest proportion (15.2%, or £1.3 billion) of procurement spend, followed by North Lanarkshire (9.1%, or £806.6 million). This is a similar pattern to that which was reported in the last report. However, since 2020 to 2021, the proportion of spend with suppliers based in Glasgow City has decreased from 25.4% of all spend to 22.5%.

The continued dominance of Glasgow City, City of Edinburgh and North Lanarkshire within the procurement spend figures is perhaps not surprising when we consider the levels of turnover generated by the businesses operating in these areas, as well as the numbers of businesses operating there. According to the Businesses in Scotland data for 2022, in most local authority areas, procurement spend was broadly in line with the level of turnover generated by registered private sector businesses in each area, and also with business numbers. This is reflected in Figure 6. While the data shows that Glasgow City, City of Edinburgh and North Lanarkshire received a high amount of procurement spend relative to their turnover, these areas nevertheless accounted for some of the highest levels of turnover in Scotland (16.1%, 11.6% and 5.5% of all turnover, respectively). They also accounted for some of the largest shares of the total number of businesses in Scotland (12.0%, 11.1% and 4.8% respectively).

The patterns of procurement spend across different local authority areas also at least partly relates to the size of the suppliers receiving spend in these areas. In particular, the predominance of SMEs in the island local authority areas may explain why these areas received lower levels of procurement spend – this is because SMEs are, by their nature, less likely to win large contracts and therefore less likely to receive large amounts of spend as a result of those contracts. As shown previously, Na h-Eileanan Siar, Orkney Islands and Shetland Islands received 0.2%, 0.3% and 0.4% of spend respectively. Figure 7 provides information on the proportion of spend that went to SMEs and to large businesses, in each local authority area. It shows that the proportions of spend that went to SMEs was greatest in these three areas. For example, in Na h-Eileanan Siar, 98.9% of spend was with SMEs, while the corresponding figures for Shetland Islands and Orkney Islands were 98.7% and 98.4% respectively.

2.4.2 Spend in Scotland by SIMD quintile

The Scottish Index of Multiple Deprivation (SIMD) classification allows us to gauge the extent to which suppliers based in communities across the socio-economic spectrum are participating in public contracts and benefiting from public sector procurement spend.[16]

Figure 8 provides a breakdown of public body procurement spend in Scotland across each of the five SIMD quintiles. This information is displayed alongside information on the proportion of all registered private sector businesses in Scotland that were operating in each quintile, and the amount of total Scottish turnover generated by businesses in each quintile.[17]

The chart indicates a good spread of public procurement spend across all SIMD quintiles; it shows that in 2021 to 2022, one third of Scottish public body procurement spend in Scotland (where SIMD classification is known) was with suppliers based in the fourth SIMD quintile, with suppliers based in these areas receiving 33.2% (or £2.9 billion) of all spend in Scotland. Suppliers in the first three quintiles – or, in other words, in the 60% most disadvantaged areas in Scotland – received almost half (48.9%, or £4.3 billion) of all spend.

£4.3bn

Almost half of all public procurement spend, totalling £4.3 billion, was with suppliers based in the 60% most deprived areas in Scotland (where SIMD classification is known).

Figure 8 also shows that levels of procurement spend in each of the five SIMD quintiles was broadly in line with the proportions of businesses operating in – and turnover generated in – each quintile. That suppliers based in the fourth SIMD quintile received the largest share (33.2%) of procurement spend largely reflects the fact that this quintile also accounted for the greatest shares in the proportions of registered businesses operating in Scotland (27.9%) and of total Scottish turnover (31.3%).

2.4.3 Spend in Scotland by urban/ rural classification

The Scottish Government’s urban/rural classification is useful in building an understanding of the extent to which Scottish public bodies are using their procurement spend to help drive economic growth in all kinds of communities.

As shown in Figure 9, in 2021 to 2022, a combined 91.1% of Scottish public body procurement spend (where urban/rural classification is known) took place with suppliers based in urban areas.[18] This is the equivalent of £8.0 billion of all spend and is consistent with the 91.4% of spend reported in these areas in 2020 to 2021.

In more detail, the largest proportion (56.2%, or £5.0 billion) of procurement spend in Scotland took place with suppliers based in large urban areas. This was followed by suppliers based in other urban areas (29.5%, or £2.6 billion).

2.4.4 Proximity of spend in Scotland

Using the Hub data, it is possible to assess the extent to which Scottish public bodies are using their procurement spending power to stimulate economic activity at the local level by contracting with suppliers in their local area.

During the reporting year, 43.3% of all Scottish public body procurement spend in Scotland was with suppliers based within the local area of the purchasing body. In value terms, this amounts to some £3.8 billion of spend.[19] This is consistent with the figures obtained for 2020 to 2021, when local spend amounted to 43.7% of all spend in Scotland.

£3.8bn

£3.8 billion (or 43.3%) of spend in Scotland was with suppliers based within the local area of the purchasing body

2.4.5 Community benefits

Community benefit requirements are an important means through which Scottish public bodies can use their procurement activity to deliver a wide range of economic, social and environmental benefits to communities across Scotland. Under the 2014 Act, public bodies must consider whether to include community benefit requirements in all contracts with an estimated value of £4 million or more, where it is relevant and proportionate to do so.

In their annual procurement reports, public bodies were asked to provide information on the number of regulated contracts awarded during 2021 to 2022 with a value of £4 million or greater that also contained community benefit requirements. One hundred and twelve bodies provided this information (85% of the 132 bodies providing a report for the year). Amongst these 112 bodies, a total of 336 regulated contracts valued at or above £4 million were awarded with community benefit requirements included. This figure represents 78% of all contracts valued at or above the £4 million threshold which were awarded by these public bodies during the year.

336

Across 112 public bodies, 336 regulated contracts worth £4 million or more included community benefit requirements.

Ninety-three public bodies (71%) also provided information in their annual procurement reports about the types of community benefits delivered during the year. An overview of the types of community benefits delivered is provided in Figure 10. It shows that the most common types of community benefits delivered were work placements (as reported by 73% of the 93 public bodies providing the relevant information), followed by apprenticeships (67%) and job creation (63%).

As a more detailed example of the types of community benefits delivered during the year, Transport Scotland noted that one of its suppliers provided employability skills training and work experience to disadvantaged young people across Scotland:

Case study: using community benefit requirements to deliver employability skills training and work experience

“Ernst & Young (EY) are providing financial advisory services […]. In 2022 EY performed mock interviews for students, attending as a ‘Dragon’ on the panel for their Dragon’s Den assignment. They carried out a presentation to the students about EY, which included what it is like to work there and how to apply.

The Smart Futures programme provides disadvantaged young people (eligible for free school meals or education maintenance allowance) in S5 with five days employability skills training followed by three days of work experience with EY. Participants are paid for these days and are then paired up with a volunteer mentor to provide ongoing employability support over the following 10 months. As various restrictions were still in place due to Covid-19, the programme was delivered entirely virtually and young people were provided with EY laptops, headsets and, where necessary, 4G dongles in order to provide them with all of the technology they would need to participate and connect to the programme. As the programme was delivered online it allowed participants to apply from across Scotland.

The EY Foundation provides opportunities for young people across Scotland. EY delivered short (half-day) employability workshops to young people in S3-S6 in multiple secondary schools in the Perth & Kinross region. In the period, this included working with 487 young people in those school year groups. These workshops were delivered in some cases virtually and in others face-to-face, depending on what Covid-19 restrictions were in place at the time of each workshop.

EY engaged with a further six young people in the Perth and Kinross region via the Foundation’s ‘Our Future’ programme, working with young people who are at risk of becoming NEET (not in employment education or training), giving them five days paid employability skills training followed by six days paid work experience with local employers. Again, this was all done virtually given the various Covid-19 restrictions that remained in place at the time.

EY worked with 20 young people from the greater Glasgow area in the Beyond Your Limits programme, which is aimed at young people in care. This two-year programme provided bite size segments of various types of support to the cohort, including six days of employability skills training, two days of financial literacy training and six days of work experience.”[20]

2.5 Good for society

The 2023 to 2028 Public procurement strategy for Scotland defines ‘good for society’ as aligning the public sector to ensure that we are efficient, effective and forward thinking through continuous improvement to help achieve a fairer and more equal society.

2.5.1 Equal treatment and non-discrimination

The 2014 Act requires that public bodies carry out their regulated procurement activity in line with the general duties of equal treatment and non-discrimination. This helps to encourage competition by ensuring that a wide range of potential suppliers are able to bid for public contracts – and this, in turn, enables the Scottish public sector to deliver better value for public money.

It is important to note that there are no legislative requirements for public bodies to provide evidence in their annual procurement reports of how they have conducted their regulated procurement activity in line with the duties of equal treatment and non- discrimination. Nevertheless, many still do so. In 2021 to 2022, 80% of public bodies provided evidence of carrying out their regulated procurement activity in accordance with these duties.

80%

Evidence on equal treatment and non-discrimination duties were included in 80% of public bodies’ annual reporting.

The annual procurement reports provided a range of examples of how public bodies are conducting their procurement activity with regard to the general duties of equal treatment and non-discrimination. For example, in their report, the Southside Housing Association highlight the importance of ensuring that all bidders have the same level of information when it comes to tendering for public contracts:

For all regulated procurement activities undertaken where possible, the Association advertised contracts at each relevant stage on the Public Contracts Scotland Portal and, when required, in the Official Journal of the European Union (OJEU).

All questions raised in procurement exercises were dealt with through the portal so that all bidders had the same information.”[21]

2.5.2 Climate change

In line with the Sustainable Procurement Duty, prior to carrying out a regulated procurement, public bodies are required to consider how they can improve the economic, social and environmental wellbeing of their area. Public bodies should also use their annual procurement reports to report on how they have used their procurement activity to help address climate issues.

In 2021 to 2022, 94 public bodies provided evidence of having addressed environmental wellbeing and climate change through their procurement activity. This equates to 71% of all bodies submitting an annual procurement report for the year.

As an example of how public bodies are using their procurement activity to contribute positively to environmental wellbeing and to address climate change, NHS NSS noted undertaking a range of actions in their annual procurement report during the year, including utilising the Scottish Government’s Climate Literacy training, which is hosted on the sustainable procurement tools:

We have created a brand new Climate Change and Circular Economy supply lead role and at the end of the reporting period advertised this role. This is a vital step for us to accelerate our delivery ambitions for de-carbonising our supply chains.

We have measured and established a baseline for our transport and delivery services … [and] our emissions in the period were 25 thousand tCO2e. We now will use this figure to measure future reductions against.

Through the SPSG we have mandated all NHS Scotland direct procurement staff pass through the Scottish Government’s Climate Literacy training to establish a knowledge base of the subject matter.

We have drafted a map of our ambitions to move towards a net zero supply chain by 2035. These ambitions will in 2022 form the basis of annual action plans to meet our goals. Work is underway on achieving 100% sustainable haddock, caught, landed and processed in Scotland for all of NHSS, which will also bring us the MSC certification…

Our medicines procurement team continue to safeguard our precious medicinal resources and keep waste down; sales from recycling short-dated stock from the national medicines stockpile exceeded £2m in the 2021 calendar year. The funds have been used to replenish the stockpile with longer dated stock of Covid-19 supportive care medicines to helping ensure stock continues to be available to meet any sudden spikes in demand. In addition to the financial benefits of avoiding waste through product expiry. Recycling is estimated to have delivered a manufacturing greenhouse gas emission reduction equivalent to 335 tCO2.” [22]

2.6 Open and connected

The 2023 to 2028 Public procurement strategy for Scotland defines ‘open and connected’ as aligning the public sector to ensure procurement in Scotland is open, transparent and connected at local, national and international levels.

2.6.1 Openness and transparency

Another way that public bodies can encourage greater levels of competition within public contracts and achieve value for money is by ensuring that they conduct their procurement activity in a manner that is open and transparent.

Again, there is no legislative requirement for public bodies to use their annual procurement reports to document how they have acted in line with these principles. Nevertheless, these reports continue to provide an insight into how openness and transparency is being achieved in practice.

In 2021 to 2022, in their reports, 111 public bodies (84% of the 132 bodies submitting a report for the year) provided evidence of having carried out their regulated procurements in accordance with the duty of transparency. For example, in their annual procurement report, Manor Estates Housing Association highlighted their endeavours to ensure transparency in the spending of their funds through the use of the PCS portal:

Manor Estates follow a procurement process when purchasing goods, services or works from external suppliers and strive to achieve value for money whilst balancing cost, quality and management of risk. Manor Estates advertises regulated tender opportunities on the Scottish Government’s Public Contracts Scotland [website], in line with Public Procurement legislation. Manor Estates does not therefore use lists of preferred suppliers.

Manor Estates encourage prospective contractors, consultants or suppliers to sign up to this online portal to receive notifications about any Scottish Public Sector contract opportunities. If any contract advertised is of interest to your company, you should follow the instructions given in the Contract Notice or advert.

For further information on individual regulated contracts, please see our contracts register on the Public Contract Scotland website.” [23]

2.6.2 International influence of Scottish public procurement

Over the reporting period, the Scottish Government continued to engage with the global commercial and procurement community. For example, in October 2021, the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) asked the Scottish Government to participate in an international conference, to share its insights on the wellbeing framework developed in Scotland, its explicit links with public procurement activities and how it supports Scotland in enhancing and ‘greening’ public spending. This was followed up by an approach from the National Association of State Procurement Officials (NASPO), who were keen to leverage learnings from Scotland, marking the start of an important partnership between the Scottish Government and the US.

Throughout the reporting year, the Scottish Government was approached by governments across Europe and further afield, to learn about its Procurement People of Tomorrow (PPoT) programme. This led to the Scottish Government being encouraged by procurement leaders to submit a case study on its professionalisation approach in January 2022.

Meanwhile, the Scottish Government continues to support the Chartered Institute of Procurement and Supply (CIPS) with membership on their Fellowship Committee, leading a survey of their international fellowship community to ascertain opportunities and interest in driving greater global engagement, and producing a recommendations report for CIPS in November 2021. Work also continued in support the CIPS Foundation and their partnership with ActionAid in Africa, helping to raise awareness of the social and economic impact that can be driven through thoughtful and progressive procurement and supply chain development.

2.6.3 Improving procurement capability and professional development

The Scottish public sector continues to take forward work to professionalise its public procurement activity. Cross- sectoral initiatives under the national professionalisation strategy target improving both current and future professional practice and talent creation within public procurement.

The Procurement People of Tomorrow (PPoT) programme addresses the challenges in attracting, developing and retaining future talent for the profession. In the reporting period, the programme launched the PPoT Pledge and a PPoT placement pack. The Pledge allows organisations to signal their commitment towards new entrants in procurement, while the placement pack provides a consistent and valuable five-day plan for students to follow when undertaking a one-week procurement placement. Early 2022 also saw aligned graduate programmes across the sectors, with APUC, NHS NSS, Scotland Excel and the Scottish Government going to market for new talent, with the commitment to connecting the graduates on these cohorts.

Scotland’s national Procurement and Commercial Training Framework was re-let in the reporting period with two Lots awarded in December 2021 on Procurement and Sustainable Procurement. For the first time, in response to demand from the procurement community, this offered ‘cost-per-place’ open training programmes nationally. Furthermore, Lot One is now delivered by a public sector partner – the Scotland Excel Academy.

To further build capability, the Sustainable Procurement Tools website continued to provide tools, guidance and training on how procurement professionals can optimise the economic, social and environmental impact of their procurement activity. The Scottish Government launched its Climate Literacy eLearning for Procurers in March 2021 – by the end of March 2022, out of the 1,209 users registered on the tools at that point in time, 853 had completed the eLearning.

853

Between March 2021 and March 2022, 853 users had completed the Scottish Government’s new Climate Literacy eLearning for Procurers.

The national standards for public procurement in Scotland are embedded in the National Procurement Development Framework. This free-to-use online tool was nearing the end of its first generation implementation in 2022, with over 1,400 user evaluations completed. These evaluations linked to learning interventions available from the national training frameworks. To build upon this success, a re-let for a second-generation tool was undertaken in the following reporting year of 2022 to 2023.

Finally, the reporting period also saw a growing investment and focus on developing commercial skills across the public sector in Scotland, with the Scottish Government’s Commercial Week (May 2021) delivering over 700 hours of continuous professional development improving commercial acumen and expertise.

2.6.4 Innovation

The Sustainable Procurement Duty mandates that before a public body carries out a regulated procurement, it must consider how, in conducting the procurement process, it can promote innovation. By ‘innovation’ in public procurement, we mean a contracting authority’s ability to influence the market towards innovative solutions; innovation may take the form of innovation in the design and delivery of public services, the procurement of innovative goods and services, or innovative procurement processes and models.[24]

The annual procurement reports enable us to understand the extent to which public bodies are complying with this element of the Sustainable Procurement Duty, while also providing some concrete examples of the ways in which public bodies are encouraging innovation through their procurement activity. Of the 132 bodies submitting an annual procurement report for 2021 to 2022, 83 (63%) provided evidence in their reports of promoting innovation.

63%

Evidence of reports promoting innovation was provided in 63% of public bodies’ annual procurement reports.

Taken from their annual procurement report, the following case study provides an insight into how Social Security Scotland adopted an innovative approach to staff recruitment. This was key in ensuring the organisation was well-resourced ahead of the implementation of a variety of social security benefits, with the organisation being the first in Scotland to undertake such a large recruitment process entirely online.

Case study: innovative approaches to workforce recruitment

“In order to deliver the next wave of benefits implementation, most notably Child Disability Payment, Adult Disability Payment and Scottish Child Payment years 6-16, [Social Security Scotland] made a commitment to increase our headcount significantly (recruitment of around 2500 full time equivalents) within an 18-24 month period.

To support this significant growth, Social Security Scotland required support from a supplier to ensure that sufficient resource would be available to assess applicants and to manage the administration of recruitment from attraction through to conditional offer stage.

The systems and service provided were required to be inclusive and accessible to support Social Security Scotland to recruit a workforce which is representative of the diversity of Scotland. The service also had to be provided virtually to allow the entire recruitment process to be delivered online.

The requirement was developed at significant scale and pace with 10 weeks available for the full design and launching. There was a significant political imperative to complete on time.

A substantial implementation team was set up… This was supported by a clear specification which focussed on a values-based recruitment process and an approach that would support diversity and inclusion so that the process wouldn’t negatively impact people from diverse groups.

The service had to be fully digital but still accessible. The recruitment process was re- designed to improve the quality and diversity of hires and also to manage organisational capacity so that hiring teams wouldn’t be taken away from delivering for our clients.

As we would be the first in Scotland to do this in a completely digital way, best practice was sought from the wider civil service with learning taken from Department for Work and Pensions and Her Majesty’s Revenue and Customs. The process was also reviewed by the Civil Service Commission to ensure compliance.

The process leveraged stakeholder partnerships with Dundee City Council, Glasgow City Council and Clyde Gateway as well as social media and more than 1,500 new offers of employment have now been made.

The diversity of our new staff was a key aim for this recruitment and analysis has shown that the make-up of the group joining us better reflects wider Scottish society.”[25]

The following case study, taken from the Scottish Fire and Rescue Service’s (SFRS) annual procurement report, is a strong example of how the organisation has used its procurement activity to foster innovation – in this case, in aiding the development of a new solution designed to improve the mobilisation of firefighters during periods of high demand for fire services.

Case study: using innovative solutions to improve firefighter mobility

“The SFRS is heavily reliant on full time and part time fighters, to provide services to the rural and urban communities of Scotland. The majority of these part time fire fighters have full-time employment, serving the local community, but who respond to emergency calls within their local area as and when required. It is critical to the operations of the SFRS to be able to quickly alert these firefighters to operational incidents within the local community. A resilient paging network is currently used to facilitate this. Changes within existing paging technology which will soon become redundant meant that the SFRS required a new solution to maintain operational resilience.

Through the support provided by the Can Do Innovation Fund, the SFRS undertook a Small Business Research Initiative (SBRI) competition, run over two phases, with the aim of developing 2 x GD92 complaint mobilising bearers … which are not reliant of the Airwave or SFRS Wide Area Network to provide resilience to mobilisation of firefighters in the communities of Scotland to operational incidents.

Phase 1 involved research and development together with a feasibility study to prove design of concept has been completed. The SFRS is now about to move on to Phase 2 which will further develop the solution in order to a prototype stage and undertake field testing.

The benefits in developing a successful solution is a high level of resilience to the SFRS mobilisation of resources, when demands for the Fire Service are greatest during poor weather, and during major civil emergencies. It is expected that the successful supplier may be able to provide the solution developed to emergency services and the public sector throughout the UK and potentially worldwide. Providing similar services to remote communities, and ensuring resilience of these critical mobilisation services is preserved.”[26]

Elsewhere, due to the success of the NHS NSS Health Innovation Assessment Portal (HIAP), a decision was made to expand the supplier-led innovation service to the entire Scottish public sector. A cross-sectoral project commenced to develop the new Scotland Innovates

service, with the aim of providing a centralised route for suppliers to submit innovative ideas in addition to providing helpful innovation guidance, news and details of relevant events through a new website. System development took place throughout the reporting year, with a planned release in summer 2022. The project also developed innovation guidance, initial triage and assessment processes and established a new cross-sectoral Triage and Delivery Board for the wider public sector.[27]

Contact

Email: ScottishProcurement@gov.scot

There is a problem

Thanks for your feedback