British Sign Language (BSL) national plan 2023-2029: consultation analysis

The independent analysis by Alma Economics of the BSL National Plan 2023 to 2029 consultation, commissioned by Scottish Government.

3. Views on the six priorities within the draft BSL National Plan 2023-2029

This section of the consultation gathered views on the six key priorities within the draft BSL National Plan 2023-2029, presented in the following order: (i) Data on BSL, (ii) BSL Workforce, (iii) Supporting deaf children, young people and their families, (iv) BSL accessibility, (v) Promotion of the heritage and culture of BSL, and (vi) Social care and wellbeing.

For each key priority, respondents were asked whether it should be included in the BSL National Plan 2023-2029, as well as the reasons for their response. Summaries of these consultation responses for the six key priorities are presented below.

BSL Data Strategy

Introduction

The Scottish Government acknowledges the need for a sustainable approach to obtaining data and evidence regarding BSL to support the actions within current and future BSL National Plans.

The consultation set out the following draft actions:

1. “To explore how a BSL Data Strategy for Scotland would work in practice, including establishing how we will gather data and evidence and distribute this in a way which helps develop sustainable approaches in data gathering around BSL.”

Question 1.1.a - What do you think about the key priority within the draft BSL National Plan 2023-2029? (Closed question)

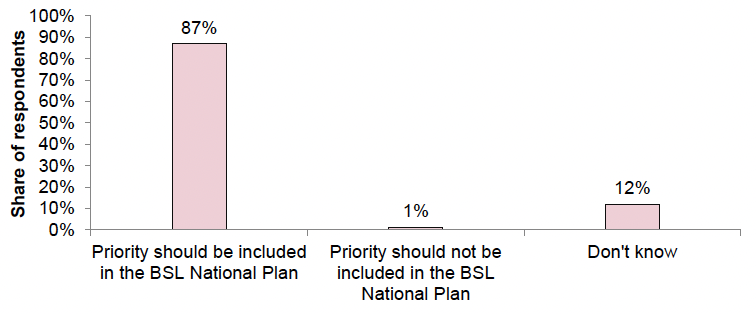

There were 76 responses to this question.

The majority of respondents (87%) supported the inclusion of Data on BSL as a key priority in the BSL National Plan 2023-2029. Only 1% of respondents were of the opinion that Data on BSL should not be included in the BSL National Plan 2023-2029. Finally, 12% of respondents answered “Don’t know”.

Question 1.1.a - What do you think about the key priority within the draft BSL National Plan 2023-2029? (Open question)

There were 61 responses to this question in the online consultation. Additionally, the thematic analysis considered findings from four community consultation events’ reports.

Importance of data to plan services

The most common theme among respondents to this question was the emphasis on the importance of collecting data to accurately identify the extent of need, and support the planning and development of evidence-based services. Policy areas mentioned by respondents where more data could drive improvement of services included education and healthcare provision. For example, BSL education policy could be informed by collecting data that would deepen the Scottish Government’s understanding of the educational attainment of deaf BSL pupils, whether they are placed in schools with sufficient BSL tutors, as well as longer-term data such as labour market outcomes of BSL users. Additionally, regarding health, a small number of respondents noted that collecting more data on topics such as the number of Deaf people and children, as well as the extent of gaps in provision for currently underserved groups, such as deafblind people, could help drive improvement in equality of access in health and mental health provision.

A significant minority of respondents emphasised that data collection is also key for monitoring progress and understanding improvement both in relation to actions in the BSL National Plan 2023-2029, but also services aimed at the BSL community more widely. Furthermore, respondents in this theme often felt that there is currently a lack of data on BSL users and the deaf and hard of hearing communities or that existing data collection is limited. A few respondents offered specific suggestions on the type of data that should be collected, including (i) the number of BSL users, (ii) the number of people in the wider deaf, deafblind, and hard of hearing communities, and (iii) data relating to the particular needs and shortages in provision for deafblind people. Additionally, a small number of respondents suggested that data collected should be able to be disaggregated by the type of hearing loss (e.g. deaf, deafblind, hard of hearing), and by demographic and protected characteristics to ensure intersectionality is considered. Finally, a small number of respondents emphasised the importance of collecting qualitative data for a more comprehensive understanding.

“Without accurate data on this population group, we will be unable to fully understand the scale of issues experienced by the community and plan accordingly.” (Organisation)

“Ensuring accuracy and consistency of data on BSL is an essential element of improving provision for BSL users across Scotland but at present there is a severe lack of evidence-based research data to inform policy decisions.” (Organisation)

Data governance

The next most prevalent theme concerned specific recommendations relating to the collection and governance of data collected as part of the BSL National Plan 2023-2029. Many respondents in this theme agreed with the imperative of developing a sustainable data collection model to underpin the BSL National Strategy. These respondents also argued that the data collection approach would have to be consistent nationally, ensuring similar data are collected across Scotland. Furthermore, a few respondents highlighted the importance of fostering policy co-creation, engaging with the BSL, hard of hearing and deaf community, and other relevant stakeholders to consult them on the data collection process and future decision-making on developing services.

A few respondents also suggested that the Scottish Government should be mindful of the potential administrative and data burden of the future BSL Data Strategy so that data collection requirements do not overburden service staff. To that end, improving existing reporting mechanisms, as well as leveraging and building on existing BSL data collection efforts, rather than designing new ones, was seen by some respondents as a solution to mitigating the risk of overburdening local authorities and other public sector bodies. Organisations that took part in the consultation often discussed particular approaches to data governance and came up with specific recommendations that depended on the respondent organisation’s particular sector of expertise (academic, third sector, local authority). Recommendations included: connecting health and social care records and adding information on a preferred mode of communicating; enhancements to Higher Education Statistics Agency (HESA) data collection requirements; wider sharing of screening data such as the Universal Newborn Hearing Screening (UNHS), as well as screening for Usher’s Syndrome, and deafblindness later in life, to allow comparisons nationally and more widely with the rest of the UK to help identify issues through studying screening patterns; standardising acquisition of the Local Records of Deaf Children; expanding the Scottish Government’s and public services’ data collection on BSL users beyond the Census, by ensuring existing data collections also collect data on BSL users (e.g., fostering closer collaboration between the Scottish Government and the Office for National Statistics to achieve the collection of data on BSL users UK-wide through existing national data collections such as the Labour Force Survey).

“Any model of evidence gathering and data collection must enable organisations to provide data in ways that are realistic and proportionate within their own context and consider how organisations can provide BSL data within existing reporting processes and requirements, rather than requiring a separate process” (Organisation)

“Improved, meaningful and reliable data is fundamental to an improved understanding of the needs of those who use BSL and consideration of how these can continue to be met. Development of a data strategy is to be welcomed, should recognise data already routinely collected and should include participation of key agencies/ bodies representing BSL users or holding data. It would be helpful to have a clearer indication of the implications and requirements for Local authorities and ensure that data gathered is relevant and proportionate.” (Organisation)

Addressing social inclusion and unmet needs

The third most mentioned theme indicated the significance of social inclusion of the D/deaf community, emphasising their equal rights as citizens and contribution to society. Respondents in this theme supported taking steps to collect sufficient data to highlight gaps in provision and lead to improvement in social inclusion and equal opportunities for the D/deaf and BSL communities. To that end, a small number of respondents mentioned the importance of collecting data for all people with some type of hearing loss and ensuring that data is inclusive of intersectionality, considering the diverse experiences of people with different intersecting characteristics. Respondents in this theme often emphasised that the D/deaf and BSL communities currently have significant unmet needs. The most common issue brought forward by those respondents was a significant shortage of interpreters, including tactile BSL interpreters. It was mentioned that better data collection could help target policies to address the areas of greatest unmet need for the D/deaf and BSL communities.

“Yes, it's important to gather the data so plans can be made in the context of the people whose lives it's meant to improve. I'm deafened and I do not use BSL […]. See Hear strategy should not ever lose sight of the wider context and the parallel needs of people with hearing loss - we may not require the same communication strategies […], but the aims are the same, surely - to have an inclusive society which gives equality of access to all.” (Individual)

“Data gathering is transformative when it is applied to progress human rights and social justice. For this reason, it is crucial that BSL data includes disaggregated data to reveal inequalities which may be concealed within aggregated data.” (Organisation)

“Anecdotal evidence of interpreters regularly 'not turning up', for example, in healthcare settings, is prevalent - however, this will continue to be solely anecdotal until measures are established to find out where in the 'booking chain' the arrangements have fallen down. A data strategy could be immensely helpful in identifying gaps and weaknesses in processes, and then we can take genuine practical steps to address the BSL community's concerns rather than offer the 'shoulder shrug' we have so often been given in the past.” (Organisation)

The BSL National Plan 2023-2029 needs to be more detailed

The next most common theme was responses in which respondents argued that the current draft BSL National Plan 2023-2029’s suggestions relating to the BSL Data priority are too broad. Respondents in this theme stressed that the BSL National Plan 2023-2029 should be more detailed, setting out specific steps linked to delivering the BSL Data Strategy. Respondents in this theme often felt that the language in the BSL National Plan 2023-2029 did not commit the Scottish Government to specific actions. It was felt that instead of setting out what will be “explored”, the BSL National Plan 2023-2029 should set out what will be delivered and include details on what data will be collected and how.

“The action relating to data needs to be more specific. Rather than ‘explore’ what to do, it would be more helpful for the action to be: 13. Establish a BSL Data Strategy for Scotland by 2027, which sets out sustainable approaches and best practice in data gathering and use around BSL.” (Organisation)

“Not enough details to agree/disagree – nothing about how to gather data. How to interview everybody? Why? What’s the purpose?” (Community Event)

Issues around consultation language, General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) and funding

A small number of respondents discussed other themes, such as inappropriate communication with the Deaf community throughout the consultation (government jargon and terminology, which was not translated into a form of BSL) and overall flaws in public sector services (absence of feedback forms in BSL).

An additional theme raised during community events related to upholding the GDPR when engaging with Deaf communities, and ensuring Deaf individuals are protected. A small number of people pointed out that data sharing should be a two-way process: councils should provide information to deaf clubs,[1] and vice versa. Otherwise, there is a risk that deaf/ deafblind people will be isolated and beyond the reach of social care services. On the other hand, mechanisms must be implemented to protect sensitive data.

A small number of people who participated in community events wanted the Scottish Government to ensure that funding goes to the Deaf community rather than hearing people who train to be BSL teachers. Furthermore, a small number of community events’ participants noted that the data collected for the Scotland Census may be misleading as it did not differentiate between deaf and hearing people who know BSL.

‘I attended an event delivered by the [organisation name]. The information provided was not clear, not only for me, but for all participants. Information was delivered using the government’s jargon and terminology, which was not translated into a form of BSL that would allow the Deaf Community to understand what was being said or asked. PowerPoints appeared to be lifted straight from the 'hearing' information, presented in a written English format that was not understood.’ (Individual)

‘Building up a national database about the Deaf community needs to be a two-way process. We will supply the SG with data, and we expect them to supply Deaf clubs or groups with data too. For example, Deaf clubs need information to make sure older Deaf people are not lonely and isolated at home. My social worker refused to share someone’s address, and this Deaf person died alone.’ (Community Event)

‘Useful to know where the funding goes to Deaf people, not just hearing people, for example, for training BSL teachers and for Train the Trainers (ToTs) courses?’ (Community Event)

BSL Workforce

Introduction

The Scottish Government acknowledges the ongoing issues regarding shortages in BSL professions in Scotland, including BSL/English interpreting and BSL tutors. This key priority aims to increase the number of BSL professionals to help address shortages in these fields and improve access to BSL services for the deaf communities in Scotland.

The consultation set out the following draft actions:

1. “Investigate opportunities for deaf and deafblind young people to learn about transitioning into and navigating the workplace, support available to them, and skills development, including how to work with BSL/English interpreters.”

2. “Work with Social Security Scotland to ensure that BSL users continue to provide input into their services in a way that is accessible to them.”

3. “To explore how a BSL Workforce Strategy alongside a BSL Data Strategy, will consider pathways including, and not limited to, BSL/English interpreting and BSL tutors/teachers.”

Question 1.1.b – What do you think about the key priority within the draft BSL National Plan 2023-2029? (Closed question)

There were 75 responses to this question.

The overwhelming majority of respondents (92%) agreed that the BSL Workforce should be included as a key priority within the BSL National Plan 2023-2029. A very small proportion of respondents (1%) were against including the BSL Workforce as a key priority in the BSL National Plan 2023-2029. Finally, 7% of respondents expressed no preference (“Don’t know”).

Question 1.1.b - What do you think about the key priority within the draft BSL National Plan 2023-2029? (Open question)

There were 60 responses to this question in the online consultation. Additionally, the thematic analysis considered findings from four community consultation events’ reports.

Increasing the number of BSL professionals

By far, the most frequent theme was concerns around shortages of BSL professionals in Scotland, including BSL/ English interpreters, BSL tutors, and Guide Communicators. Addressing this shortage was an urgent priority for respondents, considering its significant impact on accessibility to public services (such as healthcare, social services, or the justice system), education and employment, participation in democratic processes, and the ability to make informed decisions. Although shortages of BSL professionals were described as an issue across Scotland, a small number of respondents highlighted that this was significantly worse in rural areas.

The four most common suggestions given to address this were: (i) streamlining pathways to becoming a registered BSL professional for both deaf and hearing people, (ii) encouraging native BSL users to become BSL professionals, (iii) better accessibility and affordability of BSL qualifications, including more in-person options and free or low-cost qualifications, and (iv) improving career prospects for BSL professionals to make it a valued and viable option for more people.

One important consideration raised across responses was ensuring that any efforts to expand the BSL professional workforce in Scotland were combined with efforts to raise the quality of the workforce (such as through enhanced training). Concerns were expressed about the quality of existing training at advanced qualification levels, with reference to the significant negative consequences low-quality interpretation has on BSL users’ ability to access essential services.

“Lack of BSL Interpreters in Scotland is an enormous issue that is impacting this community in all aspects of their life, from schooling to health care. Even within the healthcare service, the lack of BSL interpreters is causing delays to patient care, communication issues and lack of trust from the community towards the NHS.” (Organisation)

“Priority should be given to increasing the BSL workforce in the BSL National Plan 2023-2029, given the reduction in numbers of Teachers of the Deaf in Scotland (research for/by the National Deaf Children's Society shows that the number of Teachers of the Deaf in Scotland has decreased by 40% in the past decade, with 45% of remaining teachers expected to retire over the next 10 years), investment in training is essential to mitigate a shortfall in teaching.” (Organisation)

“Some BSL/English interpreters struggled with Department for Work and Pensions/Social Security Scotland (SSS) interviews, leading to some Deaf people losing benefits. Deaf people feel it is necessary for SSS staff to have more BSL awareness” (Community Event)

Supporting BSL users to access the workplace

Increasing actions to support BSL users to access the workplace was identified as the second most common theme. This theme was more common among organisation responses to this question and was raised by almost half of total respondents. Respondents discussed targeted employability measures that support deaf young people to transition into employment, including paid work experience, apprenticeships, training programmes, qualifications, and volunteering opportunities. Employability initiatives which targeted essential services (such as healthcare) were particularly popular across responses to reduce BSL users’ reliance on BSL/ English interpreters within these services. A small number of respondents also suggested that these opportunities should take an intersectional approach and prioritise access to those from under-represented groups within the deaf community.

A small number of respondents were interested in seeing additional actions targeting older BSL users who may face different challenges in the workplace to younger BSL users, such as re-entering the workforce after redundancy, illness, or periods of unemployment. Suggestions included providing opportunities for upskilling or reskilling and targeted support to navigate career transitions.

In addition to individual support, a few respondents discussed introducing measures which target organisations directly. There were concerns that organisations were not sufficiently promoting Access to Work measures, such as grants to pay for practical or communication support at work, negatively affecting BSL users’ ability to access the workplace. One Community Event respondent reported that big organisations “can’t be bothered” with the additional administrative costs. Encouraging and monitoring the appropriate use of Access to Work was supported, as well as actions which cover employment within the private sector.

“There is a need to raise awareness and support for employability projects which provide waged work experience, support, and training to disabled people who wish to enter employment, education, or volunteering.” (Organisation)

“Investigate opportunities for deaf and deafblind young people to learn about transitioning into and navigating the workplace, support available to them, and skills development, including how to work with BSL/English interpreters.” (Organisation)

“[…] it should apply to every Deaf/Deafblind person irrespective of their age. There seems to be a lot of focus on young people, but not enough on older people who may have lost work through redundancy or ill health and who are having to transition and navigate a very different job market than they had in the past.’ (Community Event)

Additional measures to support BSL users within the workplace

The third theme discussed additional measures to support BSL users to thrive within the workplace; respondents felt that the key priority should broaden its focus to also address the challenge of retaining a job and developing a career. Although these measures should target all BSL users, this was considered particularly important for those who experience progressive hearing and/ or sight loss whilst in employment. This theme was more frequently raised by organisation respondents than by individual respondents.

It was felt that responsibility was placed more heavily on employees than employers, and a small number of participants called for workplaces to cater to all employees without having to request reasonable adjustments. Health and safety regulations were also listed during community events as factors impeding the employment of deaf people, especially since some organisations do not comply with Access to Work due to additional administrative burdens. Ensuring that any measures introduced in the BSL National Plan 2023-2029 to increase accessibility within the workplace were both mandatory and enforceable was particularly important to respondents.

“ […] it was one challenge to secure a job and another to retain one and that there should be support in place for sensory loss transitions whilst in work. Most participants have progressive sight and/or hearing loss, and there were many examples of bad practice in workplaces where people had felt ‘hounded’ or ‘pushed’ out of work. This feedback ranged across a number of professions with examples given from teachers, a nursery nurse and a couple of participants from working in retail.” (Community Event)

“Health & safety is the biggest barrier, preventing Deaf people from getting jobs because employers view Deaf people as expensive, high risk, high insurance. It means Deaf people are seen as inferior.” (Community Event)

“Many deafblind people are at retirement age by the time of onset, but for the minority who are not, the transition into deafblindness whilst in the workplace can be overwhelming with few feeling that they had access to adequate support […] This is an area where further actions could be considering including support to retain employment as for deafblind people this can be a central challenge as their hearing loss or sight loss progression often occurs in the second part of their employment years.” (Organisation)

Clarifying the implementation and delivery of this key priority

The final most frequent theme focused on the implementation and delivery of this key priority (BSL Workforce). The most frequent request by respondents was for more financial commitments by the Scottish Government within the Priority. This included the provision of sufficient funding to enable the successful delivery of any action.

Additional recommendations included clearer actions and measurable outcomes related to the key priority, as well as additional commitments to monitor and enforce the delivery of actions. A few respondents also supported more targeted guidance and support to employers (such as on the Access to Work scheme) to ensure that any efforts to increase BSL users’ access to the workforce would be adequately catered for.

“Consideration of funding and availability of training establishments across Scotland would be beneficial to ensure accessibility. There is a risk that people are trained as interpreters and tutors and there are no employment opportunities locally. Funding from the Scottish Government for 1+2 languages has ceased this year. Increasing the numbers of trained people in the workforce will require investment.” (Organisation)

“Although it is positive that the Scottish Government is open to investigating opportunities to improve the transition into the workplace, we hoped that more prescriptive actions would have been included for us to give feedback on.” (Organisation)

Supporting Deaf Children, Young People and their Families

Introduction

The Scottish Government acknowledges the impact of language deprivation on deaf and deafblind children's crucial developmental learning between the ages of 0 and 5 years, which can negatively affect their social, cognitive, and emotional development.

The consultation set out the following draft actions:

1. “The Scottish Government will investigate and explore an early intervention model for sign language acquisition for deaf and deafblind new-borns and children to ensure they and their families have access to both BSL and English. This will assess existing models to determine if we can build or improve on them. This action will help to ensure that deaf and deafblind babies and children are able to grow and thrive in an environment using the language of their choice.”

2. “Investigate the provisions of support for deaf and deafblind children within Scotland, and identify any gaps in support to inform an immediate remedial action plan. This includes BSL tuition for deaf and deafblind children and their families.”

3. “To investigate opportunities for early years workers to learn BSL up to the level of SCQF Level 6 to inform our future work in this area.”

4. “Support the development of opportunities for deaf and deafblind children, young people, and their families, to learn about the heritage and culture of BSL, especially in Scotland.”

5. “To establish a BSL Education Advisory Group to inform priorities around access to BSL and teaching of BSL, with initial focus on deaf and deafblind children.”

6. “To work with the General Teaching Council Scotland (GTCS) to explore and facilitate pathways for BSL users to obtain Qualified Teacher Status.”

7. “To investigate opportunities for Teachers of the Deaf and teachers working with deaf and deafblind children in obtaining qualifications for BSL up to SCQF Level 10.”

Question 1.1.c – What do you think about the key priority within the draft BSL National Plan 2023-2029? (Closed question)

There were 76 responses to this question.

Most respondents to this question (95%) answered that Deaf children, young people and families should be included as a key priority in the BSL National Plan 2023-2029. The opposite view was held by a small minority of respondents (1%). Finally, a further 4% answered “Don’t know”.

Question 1.1.c - What do you think about the key priority within the draft BSL National Plan 2023-2029? (Open question)

There were 59 responses to this question in the online consultation. Additionally, the thematic analysis considered findings from four community consultation events’ reports.

Importance of early intervention

The most common theme highlighted the importance of early intervention for deaf children and their families. Respondents described this as a particularly significant time for two distinct areas of child development: (i) cognitive development related to language acquisition and communication skills, and (ii) emotional development, particularly linked to social interaction and integration, the development of a secure identity, and overall wellbeing. Failing to successfully deliver this was considered to have lifelong impacts on deaf children’s educational attainment, employment prospects, and mental health.

A significant minority of respondents also called for more detailed actions, clearer timeframes, and measurable outcomes addressing early intervention within this key priority. This theme was particularly common among organisation respondents.

“[…] early intervention during the crucial 0-5 years can significantly enhance their overall development across social, cognitive, and emotional domains.” (Organisation)

“It isn't good enough to 'explore' or 'investigate' options and information. There need to be firm action points which will be delivered. This is such a key area, and investment in the early years is an investment in a child's entire future and their health and wellbeing.” (Individual)

Providing immediate access to BSL tuition

Access to free and immediate BSL tuition was identified as the next most frequent theme among respondents. The damaging short- and long-term effects of language deprivation were discussed at length by respondents, with a few describing the increased risks of social isolation and loneliness experienced by deaf children, young people, and their families as a result. Language acquisition was also understood as a key determinant of future educational attainment, employment prospects, and mental health outcomes for deaf children. Given this, respondents stressed that free and immediate access to information on both bilingualism and BSL language learning opportunities for all deaf children, young people, and their families was a fundamental right for all who needed it.

Though there was widespread consensus that all children, young people, and their families should have priority access to BSL tuition, a small number of respondents also supported an increase in BSL tuition for support staff (such as early years or healthcare workers) to ensure they are able to provide adequate support to BSL users.

Suggestions for the delivery of BSL tuition included group classes and 1-1 support, as well as specialist provision integrated within schools, colleges, and higher education. There was a preference amongst a small number of respondents for deaf instructors who were native language users in these settings, as opposed to relying on BSL/ English interpreters.

“Too often, the hearing families of deaf children are left to struggle to find the finances to learn BSL. How can this be right on a human rights basis in 2023? The families of deaf children - parents, sibling, grandparents, aunts, uncles and cousins should be able to access free BSL classes to enable their deaf child to have the best start in life. In every class where there is a deaf child, all pupils should be taught to sign to ensure that the deaf child has a peer group that can communicate with them.” (Individual)

“BSL tuition for families with deaf children needs to be funded and actioned, not just “explored”. Where do new parents go? There may be some charities doing this work, but not enough. Parents of a newly diagnosed deaf child are mostly hearing and have no access to learn BSL. These parents, wanting the best for their child, are often persuaded to have medical procedures like cochlear implants. There needs to be information about BSL and bilingualism, and clear information about where and when they can learn BSL without incurring fees or judgement.” (Individual)

Delivering holistic support for families

The next most common theme supported the provision of holistic support for families of deaf children and young people. This theme was more common among respondents who are BSL users. Amongst respondents who discussed this theme, there was consensus that medical advice was not sufficient for most families and that this should extend to emotional support and social integration. Suggestions to address this included greater access to BSL history, culture, and role models, as well as signposting community or peer support groups.

Regarding medical support specifically, a small number of respondents expressed concerns about families not being told the full range of support measures and communication methods available for their children, and reported examples of medical professionals advising against signing for children as it may impede the development of spoken language. This was considered particularly problematic for children with hearing parents who have little or no experience with deafness and BSL. Consequently, respondents emphasised the importance of placing suitably qualified professionals with comprehensive knowledge of both audiological interventions and BSL within essential services.

It was also recognised that any support provided should be tailored to the specific needs of the individual and their family. Specific examples included differences in needs between young children and young adults, as well as differences in need according to the severity of hearing loss (in which case BSL may not always be the most appropriate recommendation). Support, which accounts for each family’s diverse characteristics, through the adoption of an intersectional approach, was considered particularly important to empower parents and carers to provide children with the best support.

“You're talking about profoundly or very severely Deaf children here, who should indeed be offered the opportunity to learn BSL, as should their parents if they're hearing parents, or deaf non-BSL using parents […] access to learning BSL will not be the only way forward for a baby who has a mild hearing loss for example. The communication needs will not be the same. Signposting for parents of babies with some hearing loss should be appropriate to those needs, not some blanket BSL solution.” (Individual)

“The vast majority of deaf babies are born to hearing parents with little or no experience of deafness. It is crucial that families are given support by suitably trained and skilled professionals (in health, education, social work) and those in the third sector to allow them to access services, understand the importance of audiological interventions and equipment, support their child to develop their language and communication skills in the critical period when the brain is most adaptable and to have appropriate emotional support.” (Organisation)

“Information about these options should be presented to families in their own terms, taking into account their cultural and social background in such a way that enhances a family’s ability to make informed decisions which meet the needs of their child.” (Organisation)

Extending support beyond early years

The final theme related to extending support beyond early years. Although the importance of early identification (specifically, under age 5) and the provision of immediate support for young children and their families was emphasised across responses, as discussed above, a small minority of respondents recognised that this was not sufficient. Deaf young people are faced with new challenges which must be reflected in the support available. In particular, a few respondents were concerned about social exclusion and isolation experienced at school, and supported measures that would continue at least until 18 years of age. Transitions were considered particularly pivotal moments for young people, such as moving on to college, higher education, or employment, and respondents were supportive of introducing targeted actions to support young people through these stages.

One consideration raised across responses was that the quality of BSL tuition provided should increase appropriately with age, ensuring that young people are taught by high-quality professionals who can provide them with the skills for more complex communication.

“Why is "support for deaf children and their families learning BSL in the early years" restricted to the early years? These children do not stop becoming Deaf when they have left the early years, and their families do not need to stop learning BSL at a level that is appropriate to address their increasingly complex needs. This support should continue at least until these children are young adults.” (Community Event)

“Deaf young people who use BSL as their preferred method of communication require high quality of fluency of support which, given the lack of qualification framework for specialist and support staff, is not always available. Ensuring Teachers of Deaf (ToDs) and clinical social workers (CSWs) in schools and colleges have a minimum level of BSL qualification so that they can effectively fulfil this role is fundamental.” (Organisation)

“It is also vital that there are adequate transition processes and pathways in place as well as resources so that colleges and universities can be supported to meet the needs of users of BSL at further education (FE), higher education (HE) and degree level.” (Organisation)

BSL Accessibility

Introduction

The Scottish Government acknowledges the underrepresentation of the BSL communities across organisations and services in Scotland. This key priority aims to cultivate approaches which effectively and sustainably address the visibility, quality, and widespread availability of BSL accessibility in Scotland.

The consultation set out the following draft actions:

1. “To co-ordinate an effort with listed authorities and BSL/deaf communities within the BSL (Scotland) Act 2015 to establish sustainable approaches in the development and implementation of their BSL plans, ensuring that cost-effective work is taking place proportionately within their authorities to help their BSL plans target issues more effectively.”

2. “To develop a classification framework around British Sign Language, identifying the multiple perspectives including accessibility and as a linguistic minority, and create a guidance in partnership with the See Hear strategy to provide more consistency in approaches to BSL.”

3. “The Scottish Government will develop guidance on BSL access for public engagement, including quality assurance of BSL translations.”

4. “Review the BSL accessibility of the Scottish Government website, and work with BSL organisations to ensure a high standard of the accessibility of the website.”

5. “To consider funding mechanisms for Contact Scotland BSL, and promote the use of these services across the public sector.”

6. “To support the uptake of SignPort, an online portal for BSL/English interpreter bookings which will be launched for public use, within the Scottish Government and public bodies.”

7. “The Scottish Government will develop an Implementation Working Group for the BSL National Plan, with the aim of regularly reviewing the National Plan’s commitments to ensure it continues to meet the needs of the BSL communities in Scotland throughout the lifetime of this Plan.”

8. “The BSL Justice Advisory Group will continue to meet, with the aim to regularly review the progress on actions within Justice around BSL and to mainstream BSL into other Justice workstreams.”

9. “Explore the provision of BSL meditators/intermediaries, also known as intralingual professionals or advocates, for BSL users going through the justice system to inform work to be taken forward to support this provision.”

10. “Support public bodies within the justice sector in exploring ways in which BSL support can be accessed more efficiently for frontline work and emergency response services.”

11. “To work with COSLA and the Scottish Parliament to identify existing barriers in support for BSL users within political settings, such as councillor or MSP, and consider ways in which gaps can be addressed, including learning from the 2022 Access to Elected Office Fund.”

12. “Support the facilitation of BSL support in electoral campaigns and the election process to ensure BSL users are able to make informed decisions with access to all relevant information.”

Question 1.1.d - What do you think about the key priority within the draft BSL National Plan 2023-2029? (Closed question)

There were 75 responses to this question.

The majority of respondents to this question (96%) expressed the view that BSL accessibility should be included as a key priority in the BSL National Plan 2023-2029, compared to 1% of respondents who were against BSL accessibility being included as a priority. Finally, 3% of respondents answered “Don’t know”.

Question 1.1.d - What do you think about the key priority within the draft BSL National Plan 2023-2029? (Open question)

There were 56 responses to this question in the online consultation. Additionally, the thematic analysis considered findings from four community consultation events’ reports.

Streamlining strategy and delivery

The most frequent theme expressed concerns about the strategy and delivery of initiatives related to this key priority. This theme was discussed by over half of the respondents to this question, the majority of whom were organisations, and a large minority were not BSL users.

Regarding strategy, respondents wanted consistency and alignment (as opposed to duplication or merging) with existing strategies related to BSL accessibility, such as the See Hear strategy and the previous BSL National Plan 2017-2023 . Respondents also wanted more specific and measurable actions in the draft BSL National Plan 2023-2029. There was widespread support for a co-design approach with BSL users when deciding these, ensuring all accessibility initiatives are representative of the diverse needs and experiences of the BSL community.

When discussing the delivery of this key priority, a few respondents suggested enforcing BSL accessibility guidelines and BSL translation standards. This would guarantee consistency and high-quality accessibility across Scotland. To support this, respondents called for increased state funding to support participating services and organisations in delivering accessibility initiatives.

“More detail should be included on what this looks like, or it may be relatively meaningless as an action. BSL users and their advocacy groups should be more involved in the design and development of all accessibility plans to ensure they meet their needs and expectations.” (Organisation)

“All commitments to improve accessibility also need to be backed up with adequate resources and meet the needs of all stakeholders – to include BSL users who need the access, officers who need to ensure access is provided as standard and that the cost of access will not lead to automatic discrimination.” (Organisation)

Prioritising essential services

The second most common theme discussed was prioritising BSL accessibility and awareness within specific essential services. The most important areas identified by respondents included healthcare, social care, transport, emergency services (including the justice system and emergency healthcare), and education. Respondents were particularly supportive of mandatory BSL training for all staff within these settings – notably healthcare, emergency services, and education – to guarantee communication at the point of contact without needing to wait for or fund a BSL/ English interpreter.

Besides improved communication support across all these areas, an additional suggestion to enhance accessibility included installing visual screens to display important announcements (such as on public transport or in healthcare waiting rooms).

“BSL users should be involved in discussions around services providing transport information to ensure that BSL users feel safe using public transport and enjoy the same freedom as other citizens.” (Organisation)

“Ongoing communication with emergency professionals – e.g., in an ambulance or on arrival at a police station or mental health facility – is clearly vital to the wellbeing of all concerned, but there are systemic discontinuities within the framework which still need to be resolved. A commitment to taking appropriate steps within Scottish public services would be a welcome addition to the BSL National Plan 2023-2029.” (Organisation)

“Transport such as train stations and airports makes me worried and stressed because I can’t hear. A tannoy that has subtitles would be better for me and give independence.” (Community Event)

Increasing opportunities for BSL users

The third theme raised by respondents discussed increasing opportunities for BSL users. Besides improving access to further education (FE), higher education (HE) and the Scottish Parliament, access to high-quality employment for BSL users was the most popular priority across responses. Suggestions to achieve this included increasing BSL awareness within the workplace, widening access to supportive equipment and technologies, as well as providing enhanced support to both BSL users and organisations to improve employee retention rates.

“Our local plan would necessarily reflect the historically low numbers of BSL students studying at (organisation), and the challenges of supporting BSL users in our context.” (Organisation)

“Poor education is one of the main reasons for the deaf community being underrepresented as they have not had the same level of access to the education required to make an impact in the working community.” (Organisation)

Improving assistive technology

Improvements in awareness, training, and availability of assistive technologies were identified as the fourth theme for addressing BSL accessibility. The majority of the respondents who discussed this theme were organisations.

The majority of respondents discussed Contact Scotland BSL and SignPort, and although generally supportive of these services, they identified the need for increased funding to review and improve their offerings. This included efforts for continuous development aligned with ongoing “transformational improvements in accessibility, communication and language inclusion.” (Organisation).

More broadly, there was support for an independent digital strategy which targeted uptake by BSL users, digital exclusion (including unaffordable costs and geographical access), and digital literacy (particularly for older BSL users). Relatedly, a small number of respondents called for enhanced digital training to be delivered to both BSL users and service providers or support staff. This would ensure those providing guidance and support to BSL users are informed on what is available as well as how to use these technologies.

“More resources should be put into supporting BSL users to use new technology so that they are at the heart of all digital and technological transformations. Lack of awareness, confidence and even resources can add a barrier to the access BSL users need to get on with their daily life where many services are being provided differently and moving to digital provisions.” (Organisation)

“For increased accessibility, we would welcome and support an investment in assistive technologies to easily translate BSL to English and vice versa.” (Organisation)

Developing the BSL professional workforce

Next, increasing the quantity and quality of the BSL professional workforce in Scotland was raised as a crucial requirement to successfully deliver this key priority. This theme incorporated multiple recommendations, including: (i) increasing the availability of in-person BSL/English interpreters across Scotland, targeting BSL users who cannot access digital support, (ii) enhancing training to include BSL awareness through an intersectional lens, ensuring the communication workforce is equipped to deal with varied needs and experiences, (iii) enforcing BSL accessibility standards to ensure high-quality, consistent delivery across services and regions, and (iv) developing the communication workforce to beyond BSL (such as lip speakers).

In addition to improving access, developing the BSL professional workforce enables BSL users to choose who they would like to interpret for them. Access to choice was raised as a particularly important point, with specific mention of privacy risks when accessing certain services (such as mental health support).

“A larger pool of BSL/English interpreters is needed throughout Scotland, not just in the Central Belt, to allow the access for Deaf BSL users to be better represented across organisations and services in Scotland. Training for interpreters on these organisations and services will be vital to give them a greater understanding and knowledge on what they do and how Deaf people can contribute.” (Organisation)

“Our community shared with us that they can oftentimes feel worried about being judged or misunderstood by an interpreter, especially when discussing issues related to LGBT+ identity, which can be complex and very personal.” (Organisation)

“An overarching view was that more lip speakers are needed alongside the need for BSL interpreters and tutors. Tutor for BSL and lip speaking are needed who “must have an awareness of people who have become deafened/deaf” and be aware of the needs of those who have acquired hearing loss and those experiencing the gradual loss of hearing from mild to severe/profound.” (Community Event)

Raising awareness and representation of the D/deaf community

The sixth theme supported this key priority as a means of raising awareness of BSL and increasing representation of the BSL community within wider society. The majority of the respondents who discussed this theme were individuals.

As a result of the visibility enabled by greater BSL accessibility, it was widely acknowledged that BSL users would be both more individually independent and socially included. A small number of respondents also noted that any accessibility initiatives should be inclusive of all the D/deaf community beyond BSL users. Specific examples included increased representation (as a result of accessibility) within the news, media, films, and TV shows.

“Please don't forget that not all D/deaf people are BSL users. More and more people are being diagnosed with acquired hearing loss and are living longer. These people are at a greater risk of isolation and getting dementia than the Deaf community who have their own community.” (Individual)

Enabling civic engagement and participation

Finally, respondents were supportive of the key priority as a means of enabling civic engagement and democratic participation by BSL users.

Practically, this was described as guaranteeing access to all important information and decision-making procedures at the local and national levels. A small number of respondents also raised concerns about inaccessibility within voting processes and reliance on Guide Communicators to source key information on political parties or candidates. Televised debates were mentioned as a specific example due to a lack of BSL/ English interpreters visible on screen.

“Work has been done to ensure every other minority in Scotland has been represented in society in Scotland and in public life and politics; it is way past the time when deaf BSL users need to be encouraged and enabled to fully participate in active citizenship and in their geographical, political and social communities.” (Individual)

“Public engagement is key for Deaf people to feed into future plans and key developments within their local area which will affect them, so there will need to be sufficient access to interpreting services to allow this to happen.” (Organisation)

“Voting was discussed as a time when a language professional is needed to make the process accessible. Some participants had better experiences through the support of Guide Communicators, but overall, most people felt that accessing civic rights was fraught with barriers. Participants talked about how decisions around who to vote for are made following access to information via press, TV, manifesto leaflets, etc. Participants had not experienced formatted versions of these.” (Community Event)

The Promotion of the Heritage and Culture of BSL

Introduction

The Scottish Government recognises the vibrant BSL culture in Scotland, as well as the ongoing initiatives in heritage, culture, and the arts that showcase and celebrate BSL. This key priority gathers views on how to expand the sector in ways which will most benefit the BSL community.

The consultation set out the following draft actions:

1. “To work with organisations focusing on BSL within culture and the arts to identify priorities within the BSL communities in Scotland.”

2. “Explore existing support for organisations with a focus on heritage, culture and the arts – with a focus on BSL - across Scotland, to identify ways in which the Scottish Government can support growth for BSL in this sector, in line with the aims and ambitions of A Culture Strategy for Scotland.”

Question 1.1.e – What do you think about the key priority within the draft BSL National Plan 2023-2029? (Closed question)

There were 74 responses to this question.

Most respondents to this question, 89%, supported the proposal that the Heritage and culture of BSL are included as a key priority within the BSL National Plan 2023-2029. A small number of respondents, 3%, were against the Heritage and Culture of BSL being a key priority in the BSL National Plan 2023-2029, while 8% answered “Don’t know”.

Question 1.1.e - What do you think about the key priority within the draft BSL National Plan 2023-2029? (Open question)

There were 55 responses to this question in the online consultation. Additionally, the thematic analysis considered findings from four community consultation events’ reports.

Improves cross-cultural awareness

The majority of respondents supported this key priority as a means of improving cross-cultural awareness amongst the wider population. Almost half of all respondents to this question raised this theme, with the majority of those being organisations.

Improved awareness of BSL culture and heritage would ensure a nuanced understanding of the BSL and D/deaf community more broadly, ultimately improving social inclusion.

Moreover, the inclusion of BSL heritage and culture within mainstream representations of Scottish history is both enriching and empowering, reflecting a society that values “diversity, inclusivity, and cultural richness” (Organisation). Specific examples of how this could be implemented included integration within existing museums or displaying historical plaques and figures marking deaf heritage around Scottish cities.

“Very few people know about D/deaf culture and heritage; this would allow for more people to understand who D/deaf people are as a community.” (Individual)

“This priority is important to ensure there is meaningful engagement with the BSL community and efforts are made to understand the culture of the BSL community.” (Organisation)

“This is an extremely important area to the deaf community and typically has been excluded from contemporary culture. Including BSL would increase awareness and promote increased adoption making the community feel more valued within society.” (Organisation)

Fosters a sense of individual and social identity

The second theme highlighted the importance of promoting this key priority as a means of fostering a sense of individual and social identity. The majority of the respondents who raised this theme were organisations.

Respondents discussed feeling proud and empowered when learning about their own heritage and culture and viewed this as a right that everyone should be afforded equally. Celebration of BSL culture and heritage was viewed as a meaningful opportunity to strengthen the community, share their rich and vibrant culture, and feel more widely valued within society. This was considered particularly important for children and young people as a “foundation for engaging as confident citizens” (Organisation). The benefits listed included greater visibility of deaf role models, the development of a secure sense of identity, and reduced loneliness and social isolation.

Within this theme, a small number of respondents stressed the importance of recognising the multiple groups within the D/deaf community, including those who do not use BSL as their primary communication method and LGBTQIA+ members. The promotion of heritage and culture should acknowledge and include the diverse perspectives and experiences of all the D/deaf community.

“BSL is not just a mode of communication; it is a vibrant and distinct linguistic and cultural entity that holds immense value for the Deaf community. By promoting the heritage and culture of BSL, we are fostering a sense of identity, pride, and belonging among Deaf individuals…” (Organisation)

“Everyone’s identity/ culture and values are integral to who they are and how they operate within a community; celebrating different cultures and identities helps to bring richness to a community. Cultural connection in deaf and deafblind communities plays an important role in fostering positive mental health and should be grown to help the expansion of BSL and deaf culture, especially for young people during their transition from childhood to adulthood.” (Organisation)

“Celebrating deaf people is important; promoting deaf heritage demonstrates to deaf children that they can achieve anything.” (Community Event)

Focusing on actions, monitoring, and delivery

The next theme focused on the actions, monitoring, and delivery of the key priority. Of the large minority of respondents that discussed this theme, there was an almost equal number of individuals and organisations.

Respondents called for an increase in measurable actions within the BSL National Plan 2023-2029, as well as comprehensive strategies for monitoring and delivering any initiatives related to this key priority. For example, respondents were unclear whether the promotion of BSL heritage and culture would be conducted through education (such as inclusion within the national curriculum) or as part of the broader national culture and heritage agenda. There was also support for working in collaboration with BSL users to define the specific actions and outcomes related to this key priority.

Moreover, regarding the delivery of the key priority, respondents were supportive of increased funding to support grassroots clubs, charities, and organisations to deliver initiatives. There was also support for clarification from the Scottish Government on how funding can be accessed, as well as guidance on how to use the funding and due diligence to ensure efficacy.

“There would need to be a clearer understanding of how this would be done depending on the audience – whether it is taught in schools or is part of the national culture and heritage agenda. The inclusion of the promotion of heritage and culture into the BSL National Plan 2023-2029 will also need to highlight how organisations will access resources, funding, expertise and any support to promote this as per the BSL National Plan 2023-2029. A wider support network – for example, Visit Scotland will also ensure that along with local residents, tourists will also be aware of BSL culture and heritage as an area of interest locally and nationally.” (Organisation)

“Promoting the culture and heritage of BSL is at the heart of the BSL (Scotland) Act 2015, so it would be dispiriting to think that the next six years will be spent exploring opportunities rather than making the most of them.” (Organisation)

Developing accessibility for BSL users to culture, arts, and heritage

The fourth theme suggested that the key priority should include a focus on BSL accessibility to culture, arts, and heritage as a whole. Respondents recognised that whilst promoting BSL heritage and culture is positive, the BSL National Plan 2023-2029 must also address widespread BSL inaccessibility to mainstream culture, heritage, arts, and entertainment more broadly despite some positive improvements in this area. Specific areas raised included theatres, museums, heritage sights, and galleries.

Suggestions offered by respondents to improve accessibility within the sector included the consistent provision of high-quality interpretation, ensuring BSL-accessible events were held regularly and at suitable times, and training staff in BSL to provide immediate support and guidance.

In addition to increasing BSL accessibility as a consumer to the sector, respondents were supportive of efforts to enable BSL participation as creators through enhanced training, volunteering and career pathways.

“There are opportunities to embed BSL in the arts, media and cultural activities across Scotland by ensuring theatre performances are BSL interpreted and BSL performances are English interpreted to encourage more people to learn about and experience BSL culture. Equal opportunities for people whose first or preferred language is BSL is necessary to secure employment in the field of arts and media, improving representation.” (Organisation)

“It is also crucial to make history and heritage accessible in BSL, and to increase the representation of BSL users within the culture sector. Organisations in the arts, creative industries and heritage should provide an environment where BSL users enjoy access and services across the heritage and cultural sectors as their fellow citizens. All public events and programmes should be accessible to BSL users.” (Organisation)

Ensuring equality of access and representation

The fifth most mentioned theme viewed the key priority as a basic right for BSL users. Respondents acknowledged that access to BSL heritage and culture was often viewed as a low, non-essential priority rather than the norm despite their positive effects on mental health and wellbeing. Comments were made about other recognised languages, such as Gaelic and Scots, noting the lack of investment in widening BSL representation in comparison. In addition to heritage and culture, respondents were particularly interested in greater representation within movies, sports, and historical figures.

To ensure the promotion of this key priority is truly accessible to the wider deaf community, it was suggested that alternative communication methods besides BSL – such as loop systems, lip speaking, or audio descriptions – were included in all initiatives.

“In Scotland, BSL is recognised as a National Language, therefore, its heritage and culture should be celebrated, understood, and included. This should be part of the BSL National Plan 2023-2029 with direction to work alongside arts and culture organisations on ways to ensure Deaf culture and BSL heritage is included and considered as part of Scotland’s History.” (Organisation)

“If there are initiatives for other Scottish languages and their cultures like Gaelic and Scots, there needs to be something for BSL too.” (Individual)

“The arts are often viewed as a luxury that enhances life for the lucky; some like going on holiday. The arts need to be viewed as a fundamental form of expression that is an intrinsic part of how humans communicate their views, experiences, and distress. At times, it can replace language when experiences are difficult to articulate. Creativity has been an embedded aspect of human behaviour across the course of humanity. It can close social distance in creating safe spaces that allow people to see the perspective of others through art forms such as film, theatre, and dance.” (Organisation)

Integrating the key priority within education

The final theme identified supported the integration of the key priority within the education system. Of the significant minority of respondents that raised this theme, it was discussed equally amongst individuals and organisations.

Respondents were in favour of teaching all pupils the heritage and culture of BSL alongside the language, within academic institutions from nursery to higher education. Examples of how to implement this included teaching BSL poetry, prose, and theatre as well as introducing awareness initiatives similar to ‘Black History Month’.

“If the heritage and culture of BSL is included within a wider diversity programme in schools and for parents/caregivers and others learning the language, this will help foster the promotion of culture and heritage of the Deaf Community and others using BSL and Tactile BSL. Diversifying literacy learning in the classroom to include signed stories, poetry, film education and drama, for example, are ways of integrating and encouraging bilingualism and bimodal bilingualism.” (Organisation)

“Integrating BSL heritage and culture into educational settings enriches the learning experience for all students. It promotes cross-cultural awareness and provides a unique perspective on language, communication, and expression.” (Organisation)

Social Care and Wellbeing

Introduction

The Scottish Government acknowledges the importance of enabling all individuals to flourish in their daily lives, which includes accessing and receiving the right support for their needs. For the BSL communities, this means receiving all support and information in BSL, with an understanding of their culture.

The consultation set out the following draft actions:

1. “To explore how the National Care Service co-design involves BSL users, and includes provisions for BSL users.”

2. “Support Public Health Scotland in the development of guidance around BSL access, including use of BSL/English interpreting support in various formats.”

Question 1.1.f – What do you think about the key priority within the draft BSL National Plan 2023-2029? (Closed question)

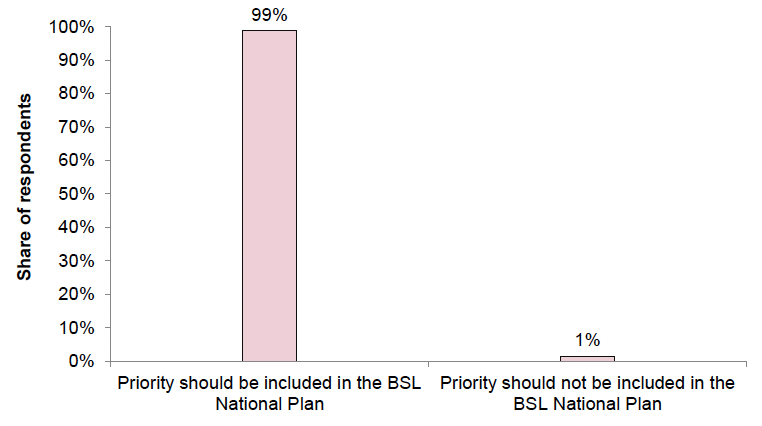

There were 76 responses to this question.

The overwhelming majority of respondents to the consultation, 99%, agreed that Social care and wellbeing should be a key priority in the BSL National Plan 2023-2029. Only 1% of respondents were against this proposal.

Question 1.1.f – What do you think about the key priority within the draft BSL National Plan 2023-2029? (Open question)

There were 53 responses to this question in the online consultation. Additionally, the thematic analysis considered findings from four community consultation events’ reports.

Increasing focus on this key priority

The most common theme was the support of this key priority, with a large minority of respondents suggesting that it should have a greater focus within the BSL National Plan 2023-2029 given the extent of the issues and barriers to access faced by the BSL community. Of the respondents that raised this theme, it was supported equally by individuals and organisations.

A few respondents did not believe the two actions (8. To explore how the National Care Service co-design involves BSL users and includes provisions for BSL users; 9. Support Public Health Scotland in the development of guidance around BSL access, including the use of BSL/ English interpreting support in various formats) were sufficient and described the situation as deteriorating since the COVID-19 pandemic.

Where respondents provided reasons for their support, these either referenced the detrimental impact of barriers to accessing social care and wellbeing services on the mental health and wellbeing of the BSL community – such as heightened social isolation, particularly for elderly BSL users – as well as the empowering effects of greater independence and equal access, should these barriers be addressed.

Specific suggestions included creating separate priorities for social care, wellbeing and mental health and expanding the key priority to include the private sector.

“100% agree with this; it is very vital for me to have the same access as hearing peers. I refuse to rely on hearing peers to help me access services, why should I? I am perfectly able to access services myself, but of course, with the daily barriers I face, I feel I am being denied the right to access the services that I pay tax for in my own language.” (Individual)

“This is a vital priority and should be included in the BSL National Plan 2023-2029. We feel strongly that sensory loss should be embedded in a number of strategies and across all services. Social Care services being accessible to the BSL community is of paramount importance.” (Organisation)

“Disappointingly, these proposals offer very little (two points focus on this, and they are very vague in nature) compared to the long list of issues the Deaf community faces. The contrast between the anxiety and concern BSL signers experience whenever they encounter poor services and the peace of mind when authorities take proactive action to ensure effective provision could not be more stark.” (Organisation)

Expanding the BSL professional workforce

The second most frequent theme was the need to expand the BSL professional workforce. Respondents identified this as both: (i) increasing the number of Guide Communicators and BSL/ English interpreters available, and (ii) training existing staff within the sector in BSL language and culture. The latter was seen as particularly important, reducing the barriers to communication for BSL users and for privacy concerns where sensitive information is disclosed. For example, a small number of respondents were increasingly worried about disclosure when working with remote interpreters. More broadly, there was support for upskilling the entire workforce (receptionists, cleaners, support workers, paramedics, doctors, etc.) with a particular focus on emergency service staff to ensure essential information could be communicated immediately (such as allergies). This was framed as especially pressing in light of BSL/ English interpreter shortages, meaning respondents often had experienced prolonged wait times.

A related sub-theme expressed the importance of having a right to choose how users access services, whether through BSL/ English interpretation or directly to deaf professionals. Choice was seen as a fundamental human right, and the expansion of the BSL professional workforce could facilitate this.

“Children of non-hearing parents should not have to translate for parents or other relatives at any appointment - medical, financial, personal both for the dignity of both parties and also for confidentiality.” (Individual)

“Accessing social care and wellbeing services in an individual’s first language as a fundamental human right. By increasing the number of BSL interpreters and support workers in the sector, BSL users will not be discriminated against when accessing social care and wellbeing services.” (Organisation)

“I always have different BSL/English interpreters at health appointments. I’d prefer the same one for every appointment. It’s important to have choices. I should not have to worry about who’s coming at every appointment.” (Community Event)

Improving mental health support

Next, the need for improved mental health support for BSL users was identified as the third most common theme. The majority of the respondents that discussed this theme were organisations.

This included tailored support for specific groups, such as the LGBTQIA+ community, children and young people, as well as the elderly. The majority of respondents discussed the increased link between deafness and mental ill health, loneliness, and increased social isolation. There was overall agreement that mental health actions from the previous BSL Plan National Plan 2017-2023 should not have been dropped and still remain an urgent priority.

Moreover, respondents requested that wellbeing services targeted to BSL users should be made more visible to the community to better understand what is already available.

“Deafness can lead to social isolation. Wellbeing and mental health services in BSL are vital.” (Organisation)

“Lots of D/deaf people struggle with mental health due to things like isolation; this part of the act would allow for D/deaf people to feel supported and have a space for them to go if they needed support.” (Individual)

“The actions make no mention of the mental health and associated wellbeing of Deaf people. Evidence-based research clearly shows the mental health of Deaf people is significantly worse than that of other groups in society. Why has this been omitted?” (Organisation)

Increasing cultural awareness

Increasing cultural awareness amongst staff within the social care and wellbeing sector was the fourth most frequent theme amongst responses. The majority of respondents raising this theme were organisations.

Respondents referenced the additional burden experienced by BSL users when needing to continuously explain their individual needs and experiences. Suggestions included enhanced mandatory training for staff to ensure the diverse needs of the entire D/deaf community can be consistently met, including intersectionality awareness, BSL family dynamics, and the LGBTQIA+ community.

“We must ensure that people are not challenged to have to explain their culture or encounter unnecessary barriers to being heard and understood.” (Organisation)

“The Scottish Government recognises the importance of ensuring that individuals can thrive in their daily lives, which includes accessing wellbeing services and receiving the right care for their needs. For the BSL communities, this means being able to receive support in BSL with an understanding of their culture as well as being able to receive information in BSL.” (Organisation)

Guaranteeing BSL-accessible information

The fifth most frequently occurring theme identified the need for consistent BSL-accessible information across the sector. This was viewed as a key action to ensure BSL users can remain independent and make informed decisions regarding their care, health, and wellbeing. The majority of respondents who raised this theme were individuals and BSL users.

Examples included providing multiple contact options for appointments (such as email or SMS/text) and ensuring announcements are delivered in BSL-accessible formats in all health and social care settings.

Moreover, respondents were supportive of enforcing accessible feedback and complaint mechanisms within the sector to ensure services continue to meet the needs of the community. An additional suggestion included increasing state funding in assistive technology to further support accessibility within social care and wellbeing.

“I previously worked in social care. I have seen so many Deaf BSL users fall through the gaps due to " professional" decisions which were thought best for the person without really discussing it with the person. This lack of person-centred care is because they do not know how to deal with BSL users.” (Organisation)

“[…] communication on issues of Public Health may carry an additional urgency.

Practice developed in communicating public health messages on Covid 19 may also provide extensive examples of good practice/lessons learned for adoption in terms of the proposed Accessibility priority.” (Organisation)

“Making information accessible in BSL is fundamental to ensuring equitable access to vital information and services.” (Individual)

Ensuring the inclusion of the whole D/deaf community

The next most common theme stated the importance of including and recognising the BSL community in its entirety within the sector as a whole, as well as any individual BSL National Plan initiatives.

Respondents stressed the need for an intersectional lens when addressing barriers to accessing social care and wellbeing services, as well as greater recognition of, and resources for, non-BSL users within the D/deaf community. Respondents also pointed to geographical discrepancies across Scotland, and urged the BSL National Plan 2023-2029 to recognise this in order to adequately meet the needs and experiences of all members of the community.

“An intersectional approach should also be adopted. For example, older BSL users might have additional barriers in accessing support and might need more preventative measures to feel safer.” (Organisation)

“I agree, but again, please don't forget about those D/deaf people who don't sign and feel isolated because they are not part of the BSL community or the hearing community.” (Individual)

Targeting care services

The urgent need for specific attention to be paid to care services was identified as the seventh most frequent theme. The majority of respondents that discussed this theme were organisations.

Respondents noted that many staff within the care and residential homes were unable to communicate with BSL-users, drastically affecting the quality and appropriateness of their care as well as their level of positive social interaction. Respondents suggested an increase in care staff trained in BSL through mandatory training requirements.

“We are extremely aware of the isolation that occurs when people who require communication support find themselves in residential or care home settings.” (Organisation)

“[…] the clients are very vulnerable to unintended abuse or lashing out as they fear they don't know why or what is being asked of or done to them. For someone with dementia, the ability to communicate diminishes and is often confusing, but without a BSL background and a dementia background staff won’t have a clue.” (Individual)

“I quiver at the thought of going into care for those reasons […] who would communicate with me? You would deteriorate fast. It has happened to me in the hospital, awful experience.” (Community Event)

Concerns regarding strategy and delivery

Lastly, respondents requested the development of a comprehensive strategy and delivery plan for this key priority. The majority of the respondents that discussed this theme were organisations.