Building a New Scotland: Our marine sector in an independent Scotland

This paper sets out the Scottish Government's vision for the marine sector in an independent Scotland.

Scotland’s seas and our marine sector

Key points:

- Scotland’s marine sector is an area of significant size, strength and value. Our seas are nearly six times larger than the land area of Scotland, and make up almost two-thirds of the UK’s Exclusive Economic Zone

- Our marine sector provides opportunities for further sustainable economic growth – both in current sectors such as salmon aquaculture, which is already the third largest worldwide, and in growing sectors such as seaweed

- Scotland has a strong track record in protecting our marine environment – such as the 37% of our seas already designated as Marine Protected Areas (MPAs) and a global leadership role on blue carbon research and knowledge exchange – but further ambitious change is needed to tackle climate change and biodiversity loss

- The full powers of independence offer Scotland the opportunity to realise the full potential of the marine sector

Introduction

Scotland is a maritime nation. Our seas, coasts and islands form an integral part of our national identity, our cultural heritage and our way of life. As we have shaped our marine landscape, so it has shaped us, our economy, our coastal communities and our outlook as a nation. With nowhere in Scotland being further than around 65 kilometres (40 miles) from a coast,[2] the sea is woven into the very fabric of life in Scotland and is a fundamental part of our national identity.

Our seas and coasts attract visitors from near and far. They offer spaces for people to enhance their health and wellbeing. They are the source of high quality seafood for markets at home and abroad. They provide communities with jobs and leisure activities. They are a source of income and employment, but also a source of inspiration and interest in sectors ranging from science to the arts.

The marine sector is important for Scotland in part because of the size and scale of Scotland’s seas. Figure 1, below, shows Scotland’s share of the UK’s current Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ). EEZs are areas of the sea where coastal countries have exclusive sovereign rights and duties in relation to natural resources, such as fish and energy resources.[3] Scotland’s 63% share of the UK’s current EEZ is an estimated 462,315 square kilometres (178,500 square miles) and is nearly six times larger than the land area of Scotland, with 18,743 kilometres (11,646 miles) of coastline.[4]

Including its entire continental shelf (areas of seabed that can extend beyond the EEZ, where countries continue to have exclusive sovereign rights over natural resources such as oil, but not fish, for example),[5] Scotland’s seas are an estimated 617,643 square kilometres (238,473 square miles) – an area around two and a half times the land area of the UK.[6]

If Scotland were to become independent and rejoin the EU, our EEZ would be the fourth largest of EU member states’ core waters;[7] larger, for example, than those of Ireland, France or Portugal.[8]

And in addition to their size, Scotland’s seas are also in a key geostrategic location between the North Atlantic Ocean, North Sea and Norwegian Sea, and in close proximity to the Arctic.

Even within the limits of devolved competence, Scotland already makes an important contribution to maritime security – of which monitoring and surveillance, tackling illegal, unreported and unregulated fishing, and protecting the marine environment and marine assets are key aspects. With independence, however, Scotland could play an increased role in responding to strategic maritime security threats in partnership with UK, EU and NATO allies and build connections that can reinforce our role as a European gateway to the Arctic.

Source: Continental Shelf (CS) (Designation of Areas) Order 2013 | Marine Scotland Information © Marine Scotland. Limits and boundaries are explained at Limits and Boundaries | Marine Scotland Information[9]

Our marine economy

Scotland’s seas are rich, providing essential natural capital, ecosystems services delivering socio-economic benefits, and jobs, income and prosperity for communities around Scotland. The opportunities created as a result encourage population growth, incentivise young people and families to stay and build lives, and play a key role in ensuring vibrant and flourishing coastal and island communities and thriving ports and harbours.

The creation and maintenance of marine jobs is especially important in rural areas where, for example, the combined “agriculture, forestry and fisheries” sector – accounted for 15% of employment in 2020, compared to 12% of employment in accessible rural areas and 0.5% of employment in the rest of Scotland in the same year.[10] Aquaculture is similarly important, with the sector and its supply chain is estimated to have supported 11,700 jobs in the Scottish economy in 2018.[11]

Additionally, seafood – caught and farmed – can contribute significantly to being a Good Food Nation. Seafood is a great source of protein, vitamins and minerals, and oily fish also contains omega-3 fatty acids which are believed to help reduce the risk of heart disease.[12]

Global production of seafood from aquaculture has increased substantially since the 1990s and fisheries and aquaculture are both recognised as essential to global food security and nutrition.[13] And there are vast opportunities for further sustainable and inclusive growth. The Scottish Government’s Blue Economy Vision sets out a broad overview of its value and significance and a set of ambitions for the long term.[14]

Scotland’s marine sector is a national asset and we have enjoyed considerable success in marine fields, including:

- a marine economy that generated £5 billion in Gross Value Added (GVA) in 2019 – of which £1.88 billion was generated by fishing, aquaculture, processing and marine tourism – accounting for 3.4% of the overall Scottish economy and providing employment for 75,490 people. The sector is particularly important for coastal and island communities where alternative forms of employment can be limited. This includes, for example, areas such as Shetland where the marine sector accounted for 19% of total GVA and 17% of employment in 2019[15]

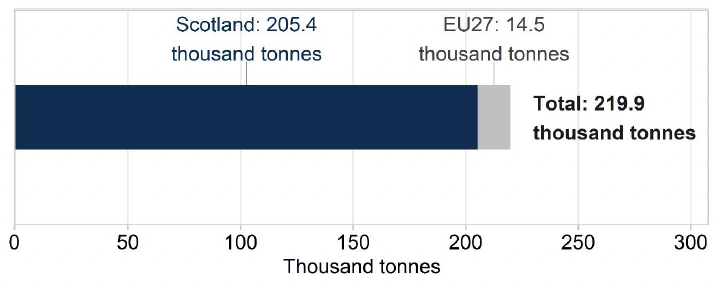

- the third largest salmon aquaculture industry worldwide[16], with Scottish-farmed Atlantic salmon being the UK’s biggest single food export[17] in 2022 and a sectoral turnover of £1.5 billion in 2018.[18] Scotland accounted for approximately 93% of EU plus UK (‘EU28’) Atlantic salmon production in 2021, as can be seen in Figure 2 below.

Source: Scottish production: Fish Farm Production Survey 2021, Table 1, Marine Directorate, 2023; EU27 and rest of UK production (estimated): Global Production by Production Source – Quantity (1950-2021), Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, 2023 (last accessed 6 November 2023); Marine Directorate calculations based on production dataset search of EU member states and UK[19]

- 62% of the value and 67% of the tonnage of all landings by UK fishing vessels[20] in 2022. Scotland also has three of the top five largest ports for seafood landings by tonnage in the UK with Peterhead accounting for just under ten times the tonnage of landings into the largest English port (Newlyn) and more than four times the value of the largest English port by value (Brixham) in 2022.[21] Prior to Brexit, the Scottish fleet landed 8% of the EU total – the fourth- most productive fleet in the EU.[22], [23]

- world-class, nutritious and low carbon seafood products enjoyed at home and abroad, with Scottish overseas seafood exports valued at over £1.0 billion in 2022 and the Scottish seafood sector contributing £1.3 billion to the Scottish economy in gross value added in 2019.[24] In 2021, our seafood sector accounted for 60% of Scotland’s food exports, compared to 4% for the rest of the UK[25]

- 43% of the UK’s seafood processing jobs, with 3,367 full time equivalent jobs in North East Scotland alone in 2021[26]

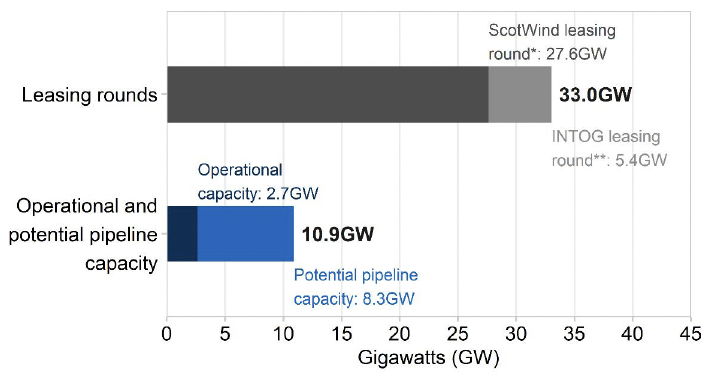

- ScotWind, is the world’s largest floating offshore leasing round and a project of national importance with – as can be seen in Figure 3 below – market ambitions to deliver up to 27.6 GW of capacity.[27] This is roughly double our renewable energy generation capacity currently in operation, and compares to peak electricity demand in Scotland of between 5-6 GW.[28], [29] It is also in addition to 2.7 GW of existing operational offshore wind installations and an 8.3 GW pipeline of projects in planning, consented or under construction[30], [31] ahead of ScotWind leasing results

- Innovation and Targeted Oil and Gas (INTOG) – a current planning and leasing process designed to enable opportunities for offshore wind projects to help decarbonise offshore oil and gas activity. It also allows for smaller innovative projects to gain access to seabed. If all projects come forward, the INTOG round could see an additional 5.4 GW subject to planning and consenting decisions and finding a route to market.[32]

Source: Scottish Energy Statistics Hub, Scottish Government, Q2 2023 (last accessed November 2023); Crown Estate Scotland, ScotWind leasing round – Offshore Wind (last accessed July 2023); and INTOG ¦ Innovation and Targeted Oil and Gas leasing round | HIE, Offshore Wind Scotland. * Current reported potential; projects will only progress to a full seabed lease once various planning stages have been completed. ** subject to planning and consenting decisions and finding a route to market.

In addition to these established industries, Scotland has exciting, emerging marine industries, which provide an increasing number of high quality jobs in rural and island areas. These include, for example, sea eagle tourism which is now estimated to support between 98 and 160 full time jobs on the Isle of Mull (population 2,800) alone[33] and a seaweed sector estimated to be capable of supporting up to 490 full time equivalent jobs directly, and in the wider supply chain, by 2040.[34]

Our marine environment

Our seas and marine environments are not only valuable in economic terms, they are also immensely rich in an environmental sense.

They have an important role to play in Scotland’s transition to a wellbeing economy – a strong, growing economy which is environmentally sustainable and resilient, which serves the collective wellbeing of people first and foremost and which takes a broader view of what it means to be a successful economy, society and country rather than focussing solely on traditional measures of prosperity.

Scotland’s marine environment is productive, but also hugely diverse. It supports an estimated 8,000 species of plants and animals – and up to 40,000 species if microscopic organisms are included[35] – with new species still being discovered, particularly in deeper waters to the north and west.

Scotland’s seabirds are of international importance, with 24 species regularly breeding here, and Scotland hosting 56% of the world’s breeding population of great skua and 20% of the world’s northern gannet.[36] We also have 37% of the world’s population of grey seals, one of the largest kelp forests in Europe and – in our riverine marine environment – much of the world’s population of freshwater pearl mussels.[37]

Scotland also has a range of important marine habitats such as salt marshes, kelp forests and seagrass meadows which – in addition to their economic and recreational benefits – provide significant environmental benefits such as carbon capture, natural coastal erosion defence, pollution control and water purification.[38]

However, our seas and marine resources are also under pressure from increasing spatial demands[39] and habitat loss.[40] It is vital that we protect and enhance our marine environment and biodiversity so that they can benefit current and future generations, and preserve the natural capital that our marine industries depend on.

Scotland already has a strong track record, with 37% of our seas designated as Marine Protected Areas (MPAs),[41] compared to the EU’s Biodiversity Strategy target to establish protected areas for at least 30% of EU seas by 2030.[42]

Further bold and ambitious change is now needed, which is why we have also committed to other measures through the Bute House Agreement[43] such as:

- delivering fisheries management measures for existing MPAs where these are not already in place, as well as for Priority Marine Features at risk from bottom towed fishing gear outwith these sites

- taking specific, evidence-based measures to protect the inshore seabed in areas outwith MPAs, with consultation on a cap on inshore fishing activity at current levels up to three nautical miles as an interim measure

We are also developing a new pathway to enhancing marine protection, in broad alignment with the approach being taken by the EU, and in a way that is fair, just and which empowers communities and shares in the benefits of a green economy.

While our seas and marine environment face grave risks from the twin crises of climate change and biodiversity loss, they also provide important opportunities to address these challenges.

That includes, for example, Scotland’s huge offshore wind and tidal energy potential – as outlined in our Draft Energy Strategy and Just Transition Plan[44] – which forms a critical component of our transition to net zero by 2045.

There is also a growing recognition of the role our seas can play in key mitigations such as carbon sequestration – with our marine and coastal environment already storing roughly the same amount of carbon as land-based ecosystems such as peatlands, forestry and soils.[45]

Scotland is already undertaking internationally recognised blue carbon research[46] to build an evidence base and inform policy development and – building on our leadership at COP26 – is supporting blue carbon knowledge exchange with international partners such as Australia.

Through these, and other linked activities, there is a significant opportunity to maximise the potential of blue carbon nature-based solutions to benefit the climate, biodiversity and people – not only in Scotland, but also in the Global South.[47]

Our outlook

Scotland is not only a proud maritime nation, but also a firmly European nation – geographically, culturally and economically. We share the European commitment to working multilaterally to tackle shared challenges such as promoting sustainable fisheries, protecting our shared marine environment and harnessing our marine space to tackle climate change.

Scotland’s marine expertise and approach to marine management and planning are widely respected. For example, the adoption of Scotland’s National Marine Plan in 2015 came six years ahead of the relevant EU directive requirement[48] and we enjoy significant influence on the international stage, consistently punching above our weight – including hosting high profile international events such as COP26[49] and important international conventions such as the North Atlantic Salmon Conservation Organization.[50]

And far from being a barrier, or leaving us geographically isolated, Scotland’s marine space is a bridge, connecting us to Europe and the wider world and binding our interests – creating shared challenges but also shared opportunities.

With the right support, our marine area can provide more high quality jobs, ensure a sustainable future for our coastal and island communities, be an even greater source of clean, green energy, and continue to provide a beautiful environment to share and enjoy; both now and for future generations to come.

With current powers, however, the Scottish Parliament and Government simply do not have all those tools at their disposal, or the ability to make relevant decisions and choices in Scotland’s best interests.

Contact

There is a problem

Thanks for your feedback