Building a New Scotland: Migration to Scotland after independence

This paper sets out the Scottish Government's proposals for migration policy in an independent Scotland.

Migration and population

Scotland's population was 5,436,600 on 20 March 2022, according to the recent census. This is the highest figure ever recorded. Scotland's population is still growing, but that growth is slowing.[3]

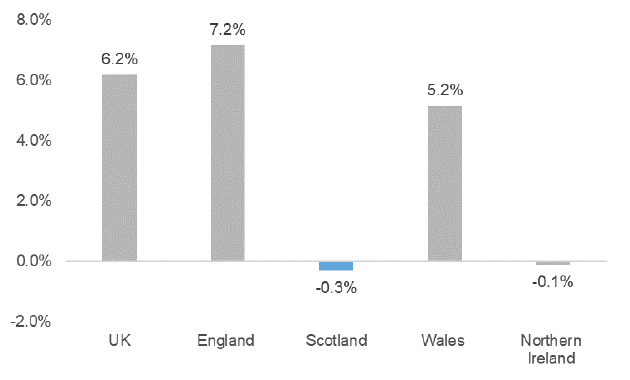

The population grew by 141,200 (2.7%) since the previous census in 2011. This is a slower rate of growth than between 2001 and 2011, when the population grew by 233,400 (4.6%). The other UK censuses showed higher rates of population growth than in Scotland. In England and Wales, the population increased by 6.3% between 2011 and 2021. In Northern Ireland, the population increased by 5.1% over the same period.[4]

There were 62,941 deaths and 46,959 births in 2022, or nearly 16,000 more deaths than births. This was the largest natural decrease in a year on record and there were more deaths than births for the eighth year running.[5]

There were 2% fewer births than the previous year, continuing a declining trend in births in Scotland seen in previous years. This is the lowest number of births since 2020, and the second lowest since records began in 1855. The number of deaths fell by 1% compared to the previous year.[6]

Migration continued to be the sole driver of population growth, with 27,800 more people moving to Scotland than leaving in the year to mid-2021. This represented net migration of +8,900 from the rest of the UK, and +18,900 from international migration.[7]

The COVID-19 pandemic will undoubtedly have had some effect on these figures, both in terms of travel restrictions impacting decisions to move to Scotland and sadly on the number of deaths recorded.

Other factors that are likely to affect population numbers over the long-term include the challenges of declining fertility and an ageing population, the political and policy environment around immigration in the UK, and the ending of free movement from the EU.

Public attitudes to migration

The first in-depth, representative survey of attitudes to immigration in Scotland since 2014,[8] research carried out by Migration Policy Scotland and published in September 2023,[9] found that attitudes to immigration in Scotland have warmed considerably. Key findings show that a majority (59%) of people in Scotland believe immigration has had a positive impact on Scotland; 48% believe it has had a positive impact on their local area.

A greater proportion of the Scottish public think immigration should be increased (38%) rather than decreased (28%), although those in favour of an increase mainly support a modest increase, while those supporting a decrease are more likely to want it to be reduced 'a lot'. Around a third (34%) think immigration should 'remain the same as it is'.

The report presents the Scottish survey data alongside data from two UK-wide surveys conducted earlier in 2023 (see Table 1, below).[10] While the surveys compared are methodologically distinct and therefore not directly comparable, they indicate higher levels of support in Scotland for a (modest) increase in immigration and lower appetite in Scotland for reducing immigration than is apparent in the UK-wide data.

Do you think the number of immigrants coming to [Scotland/ Britain] nowadays should be: |

MPS Attitudes Survey (Scottish data) |

Ipsos/British Future Tracker[12] (UK data) |

Kantar Public & Migration Observatory[13] (UK data) |

|---|---|---|---|

Increased (a little, a lot) |

38 |

22 |

14 |

Remain the same |

34 |

22 |

22 |

Reduced (a little, a lot) |

28 |

48 |

52 |

Don't know |

N/A |

8 |

12 |

The last survey that allowed for direct comparison between results from Scotland and other parts of the UK on this question was conducted in 2014.[14] At that time most people in Scotland wanted immigration to decrease (58%), but far fewer than in England and Wales, where 75% wanted to see numbers reduced. The proportions in favour of an increase were similar for both nations at 10% (Scotland) and 8% (England and Wales); 23% and 13% respectively wanted immigration to remain the same.

Population projections

In January 2023, the Office for National Statistics published a revised population projection for Scotland. This projection reflected higher than anticipated international migration to the UK

than the previous 2020 projections. While this meant that the projection was a bit higher, it still predicts Scotland's population to begin falling in around a decade's time. It is projected that by 2050, the population of Scotland will be lower than the mid-2020 baseline.[15]

As shown in Figure 1, below, the population of Scotland is anticipated to peak around the year 2033, at a population of 5.53 million, before starting to fall.

Source: Office for National Statistics (2023) Projected Population of Scotland (2020-based)

The Office for National Statistics prepares the UK projections, which show that the population of the UK as a whole is projected to grow by 6.9% to mid-2045.[16] Scotland is predicted to undergo less growth than the other UK nations in that timeframe, with an increase of 0.2%.

Scotland's population is also projected to age. The number of people aged 65 and over is projected to grow by 26% by mid-2045. The number of children is projected to decline: the number of people in Scotland aged 0-15 is projected to fall from 901,200 in mid-2022 to 739,200 by mid-2045 – a decline of 18%.

The working age population is projected to decrease slightly by mid-2045. In mid-2022, there were approximately 3.56 million working age people in Scotland, making up 64.9% of the population. In mid-2045, the working age population is projected to be 3.55 million, making up 64.6%. Scotland is expected to see the largest decline in the number of working age people in the UK – the segment of the population most likely to be in employment and contributing to the tax revenues that fund public services.

Source: Office for National Statistics (2023) Projected Population of Scotland (2020-based)

If these projections are realised, Scotland's share of the UK population overall will fall from 8.1% in mid-2020 to 7.6% by mid-2045.

These projections are based on past trends and assumptions about future levels of fertility, mortality and migration. They are not based on predictions about future political and economic changes or the future effect of current policy decisions. They do not account for the ending of free movement and changes to the UK immigration system. It is therefore possible that these projections may be based on an optimistic interpretation of future migration trends under the current constitutional arrangements.

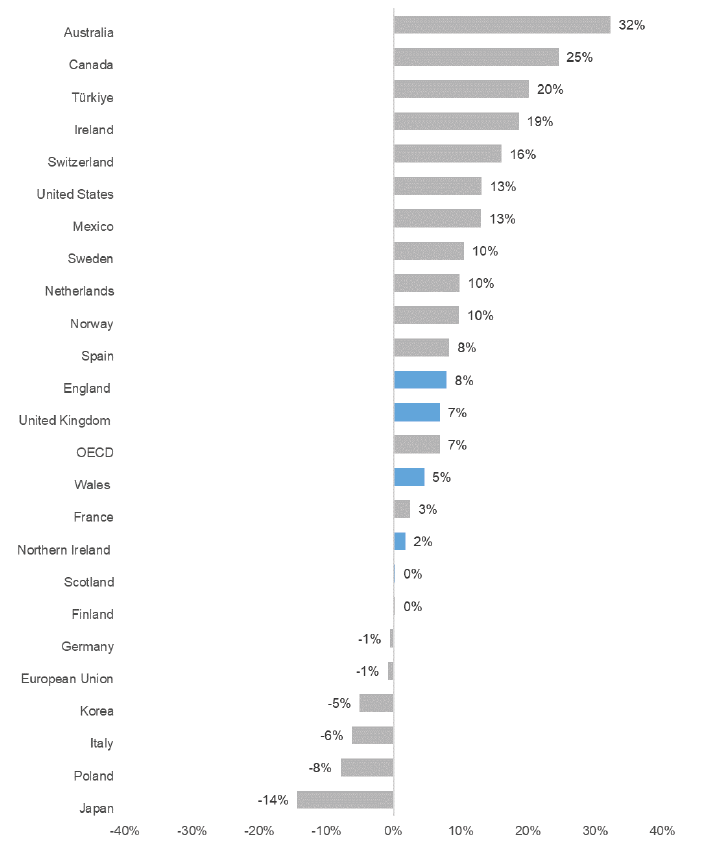

Figure 3, below, shows projected change in the population of the UK compared to selected OECD countries, 2022-2045. It highlights that whilst the UK's overall population is expected to increase by 7%, Scotland's population remains stagnant during this same period and both projections are significantly lower compared to the majority of neighbouring EU countries.

Source: Office for National Statistics (2023) Projected Population of Scotland (2020-based)

1 England, Wales, Scotland, and UK based on 2020 ONS migration variant projections, Northern Ireland based on 2020 NISRA projections; Source: 2020 ONS Projections

2 OECD projections; Source: 2023 OECD Population Projections

Role of migration policy

Migration from EU countries has been particularly important for Scotland over recent years, but Brexit and the Westminster government's refusal to recognise the need for a tailored approach to immigration policy to address Scotland's particular needs for people and skills risks significant problems for Scotland's economy.

The independent Expert Advisory Group on Migration and Population[17] has estimated that changes to UK immigration rules could decrease EU migration to the UK, increase non-EU migration and overall lead to a net 30% to 50% reduction in net overseas migration into Scotland.[18]

The Expert Advisory Group also found that ending of free movement disproportionately affects rural areas and therefore there may be an even more significant effect on these communities, many of which are already most severely affected by depopulation.[19] This is now beginning to be seen in the data – with the effect of UK immigration policy being to concentrate migration even further into London.[20]

For the past two decades, migration has been the main driver – and for the past seven years the only driver – of population growth in Scotland. All of Scotland's future population growth is still projected to come from inward migration, both from other parts of the UK and from outside the UK, but at a lower level than before.[21] Immigration is therefore a central policy lever to address Scotland's demographic challenge. Control of migration policy would give Scotland the powers and range of policy options to address its demographic challenges and the distinct needs which these challenges create for our economy, public services and communities.

The Scottish Government has made repeated attempts to propose alternative approaches to migration policy for Scotland.[22],[23],[24] These attempts have acknowledged that there are different perspectives on migration in different parts of the UK and have suggested tailored approaches specific to Scotland, building on the previous success of the Fresh Talent initiative.[25] The government's detailed policy paper was dismissed by the Westminster government within hours of its publication.[26] This is despite the Westminster government's own Migration Advisory Committee (MAC) recommending the delivery of bespoke migration schemes which are tailored to localised communities and their needs.[27] Instead, the current Westminster government's immigration system ties many visas to a specific job with a specific employer, with extensive in-country compliance measures to ensure that this restrictive requirement is adhered to.[28]

Population decline in Scotland is being ignored and made worse by the Westminster government's migration policies. Scottish Ministers propose that independence would now be the only way to mitigate the risk of population decline – with control of our own policy on migration, resuming free movement as an EU member state and retaining free movement with Ireland and the UK through the Common Travel Area.

Population Strategy

In March 2021, the Scottish Government published Scotland's first population strategy, 'A Scotland for the future: opportunities and challenges of Scotland's changing population'.[29] The strategy sets out the cross-cutting demographic challenges that Scotland faces at national and local level and sets out a new programme of work to address these challenges and harness new opportunities.

The strategy identifies 36 initial actions across four thematic building blocks:

- a family friendly nation – as Scotland's birth rate is falling (and is the lowest in the UK), we must ensure Scotland is the best place to raise a family

- a healthy living society – as Scotland's population ages, we must ensure that our people are healthy and active

- an attractive and welcoming country – with the end of free movement, Scotland needs to be able to attract people who can make a positive contribution to our economy, communities and public services

- a more balanced population – with rural communities, and some parts of the west, experiencing population decline, while many in the east experience increased population growth, we must ensure all our communities can flourish

The strategy is the beginning of a conversation. The Scottish Government is working collaboratively with partners to deliver the initial actions set out in the strategy and to continue to build evidence, engagement and energy to address this national challenge. But without control of migration policy such interventions, while important, will inevitably be constrained and less effective.

Economic impact of migration

The Scottish Government believes inward migration has had a positive cultural impact on Scotland. Scotland's economy also benefits significantly from migration. People who have chosen to live and work in Scotland are helping to grow our economy, address skills shortages within key sectors and make an essential contribution to our population growth. Policy choices made by the Westminster government put this at risk.

Migrant workers can have a positive effect on the host country and can contribute to higher economic growth.[30] This growth can be achieved through incoming migrants providing a boost to the labour supply, thereby expanding the productive capacity of the economy. This can result in higher levels of economic activity and employment, making the whole economy more

competitive. As well as adding to the supply side of the economy through expansion in the labour force, migrants also contribute to increased demand for labour through expansion of consumer demand for goods and services in the economy.

Migration is also associated with increased productivity and innovation. Various studies conducted on behalf on the Migration Advisory Committee find that a one percentage point increase in the migrant share of the workforce is associated with a productivity improvement of between 1.2% and 3% in the UK.[31] A summary of the available evidence by the Bank of England also suggests migration by EU workers boosts long-run GDP per capita, both through increasing diversity and complementing skills and a greater degree of patenting. The summary also found strong links between migration and increasing trade.[32],[33]

Migrants can also make specific differences in key sectors through strengthening and supplementing local skills, as well as by taking up jobs in regional economies that are otherwise hard to fill. Some studies have found evidence that migrant and native workers specialise in different types of skills,[34] which could increase specialisation and productivity gains. Evidence shows that migrants are also more likely to establish new businesses, generating employment opportunities. Research from the Federation of Small Businesses found that one in ten SMEs in Scotland are immigrant led.[35] Migrants can also boost innovation, with recent research finding that migrants bring knowledge that reshapes patenting activity in the destination country.

Countries are around 25% to 60% more likely to gain advantage in patenting technologies given a twofold increase in foreign inventors from nations who specialise in those same technologies.[36]

Furthermore, migrants contribute more to government revenue through taxes than they receive in public services.[37] Recent work by Oxford Economics for the MAC confirms this finding in a UK context. This study concluded that both EEA and non-EEA migrants are expected to make

a significant positive net contribution to the UK public finances. The future net contribution of 2016 arrivals to the UK public finances is estimated at £26.9 billion, or about 1.3% of GDP.[38] The fiscal contribution of that cohort of migrants to the UK public finances was estimated to be approximately equivalent to the additional revenue from adding five pence to the rate of each UK income tax band in one year.

This work contributed to a major review by the MAC, which also found that overall there is little or no evidence that migration has a negative effect on wages, public service access or employment and training opportunities for the resident population.[39] There is some evidence of a negative impact on wages in the lowest-skilled and lowest-paid occupations, but this is marginal, and with powers over employment law we can seek to improve earnings for those on the lowest levels of pay. The focus on salary thresholds in the UK immigration system does not appear to have any substantial impact on relative wages.[40] Independence and control over migration policy would enable Scotland to shape the interaction between immigration policy and other additional new powers such as employment law, ensuring workers' rights are protected and preventing exploitation and abuse in line with our fair work principle.

In the long term, population decline combined with trends of ageing is likely to have far-reaching implications for Scotland – including impacts on Scotland's fiscal position and resultant public service planning and provision. In the near term, labour supply shortages are a significant constraint on economic recovery and growth. Both are made worse by UK Government policy priorities on immigration.

Previous Scottish Government modelling simulated three scenarios based on long-term increases in net overseas migration of 5%, 10% and 20% to provide an illustration of potential impact on GDP and revenues.[41] Previous modelling simulated scenarios based on a long-term annual increase in net overseas migration above the level assumed in the high migration variant of the ONS 2016 projections for Scotland and assumed no change in net migration from the rest of the UK. At the time, the high migration variant was closer to the actual data on net migration. The Office for Budget Responsibility also judged in its November 2016 forecast report that without the Brexit referendum it would be more appropriate to base forecasts on the high migration variant.[42]

Higher migration under these three scenarios results in a growing working age population, which leads to more economic activity and employment, leading to a long-term increase in real GDP equal to 0.4% (£0.5bn), 0.8% (£0.9bn) and 1.6% (£1.8bn). Moreover, the increase in economic activity has a positive impact on real government revenues which rise by 0.3% (£0.2bn), 0.7% (£0.3bn), and 1.4% (£0.6bn) respectively.

If control over migration policy could achieve higher levels of migration into Scotland, then our economic modelling suggests that a growing labour force would have a positive economic impact.

Supporting key sectors

Some sectors in Scotland have relied on a higher proportion of non-UK workers within the workforce: before the pandemic, large portions of the workforces in Food and Drink (15%) and Tourism (16%) workforces were non-UK nationals.[43] Sectors such as Accommodation and Food Services, which are crucial to Scotland's tourism sector, were significantly impacted by the pandemic, and have experienced ongoing difficulties with recruitment and worker shortages.[44]

The ability to set immigration policy after independence would create the opportunity to pursue an open and flexible approach to migration across the system. It could be made responsive to the needs of all parts of the economy and all parts of Scotland and thereby support a range of sectors currently experiencing challenges.

The case studies in this section highlight sectors of central importance to the Scottish economy, often including employment in rural communities, which are currently experiencing labour shortages as a consequence of Brexit ending free movement from the EU and the Westminster government's immigration system not being designed to meet their needs.

Case study 1–Tourism and hospitality

Scotland's tourism and hospitality sector is an important part of the Scottish economy, and a key employer both in rural Scotland and our principal cities. The industry has also relied on the skills, talents and dynamism of international workers in recent years, particularly those from the EU. In 2020, non-UK nationals represented around 19% of the workforce in the accommodation and food services sector, which forms the substantial part of Scotland's tourism and hospitality industry. As part of this, EU nationals represented around 14.7% of the accommodation and food services workforce, compared with 6.4% of the workforce in the Scottish economy overall.[45] The sector's success is therefore strongly exposed to the challenges presented by Brexit and the Westminster government's approach to its aftermath.

The Accommodation & Food Sector, which comprises a substantial part of the tourism and hospitality sector, experienced significant challenges during the pandemic, and is still experiencing challenges with worker shortages and filling vacancies. The latest Business Insights and Conditions Survey indicated that 44.5% of Accommodation & Food Services businesses had experienced worker shortages, a higher portion than other sectors.[46] The sector has ongoing recruitment challenges: for example, 36.1% of Accommodation and Food Services businesses experienced difficulties recruiting employees in August 2023. Previous BICS data indicates that factors underpinning recruitment difficulties included 'low number of applications' and a 'lack of qualified applicants'. However, reduced numbers of EU applicants have also tended to be a key factor cited by Accommodation and Food Services businesses experiencing difficulties in filling vacancies, with higher shares of businesses citing this as a factor compared to businesses experiencing difficulties in the economy as a whole.[47]

Immigration policy has been highlighted as a key area of concern by bodies such as UK Hospitality[48] and the Scottish Tourism Alliance.[49] UK Hospitality has also highlighted that due to challenges with population growth, immigration is an important means of addressing the labour supply issues of Scotland's hospitality sector, particularly in rural areas.[50]

Case study 2 – Agriculture

Productivity is key to the future success of the Scottish agri-food industry, a key growth sector of the Scottish economy. The Scottish food and drink sector and the Scottish Government's joint target to increase the sector's turnover by 25% to £20 billion by 2028 will not be reached if the sector cannot employ workers throughout the food chain.[51]

Seasonal migrant workers play a key role in the Scottish agricultural sector, in particular in the horticulture (fruit and vegetable production) and the potato sector. Recent research estimated that there were around 6,570 seasonal migrant workers in Scottish agriculture in 2021, including EU settled status workers.[52]

Employers in the UK have found it difficult to source domestic labour to take up seasonal employment on farms (Findlay et al. 2010). In 2020, despite the widely publicised Pick for Britain campaign, UK residents made up only 11% of the workforce (NFU 2020). Domestic recruitment in 2021 was at 5% for Scotland (NFUS 2021). Part of this is related to rules associated with unemployment support which makes it unattractive for locals to take up seasonal employment. Therefore, migrant workers are filling roles not taken up by the national workforce.[53]

Horticultural places on the Seasonal Worker Visa were capped at 45,000 for the whole of the UK for 2023 and 2024. There is potential for a further 10,000 additional visas for horticulture if demand is proven.[54] This arbitrary cap falls far short of the estimated 70,000 workers required by the sector according to the National Farmers Union.[55]

Employers of seasonal migrant workers reported serious negative consequences for their businesses should they not be able to access this type of labour. This included downscaling business, focussing on non-agricultural activities, switching to other agricultural activities (e.g. cereals or livestock) and ceasing current activity.[56]

In addition, there are increasing concerns about exploitation of migrant workers as highlighted in the results of a 2021 report by Focus on Labour Exploitation, which explored exploitation, trafficking and standards, highlighting the particular vulnerability of seasonal migrant workers to these issues.[57]

The Scottish Government is fully committed to tackling human trafficking and exploitation and developing Scotland as a world-leading Fair Work Nation. We want economic growth here to be inclusive. The Scottish Government has therefore funded the Worker Support Centre[58] to offer free, impartial and confidential support and information to seasonal migrant workers to help them understand their workplace rights and to feel safe and welcome in Scotland.

Case study 3 – Creative industries and events

Scotland's creative industries sector, which encompasses the culture and arts sectors, contributed £4.4 billion GVA to the Scottish economy in 2021 and produced international exports worth £1.7 billion.[59] The people who make up this part of the economy are inherently internationally mobile as there are a limited number of individuals with highly specialised skills in the world. In 2021, the Scottish Arts, Culture and Creative sector employed an estimated 164,000 people including around 49,000 who were self-employed.[60] The workforce included around 9,000 non-UK nationals in 2019, standing for 7.3% of the total creative industries' workforce.[61] However, the culture and creative sectors are diverse, with some sub-sectors having higher proportions of non-UK employees. For example, in 2018 Scotland's National Performing Companies reported that around 18% of their total workforce were non-UK citizens – rising to 54% for Scottish Ballet.[62] This reflects the nature of the sector in relying on attracting talent from around the world.

With the policy levers that come with independence, Scotland could design an immigration system that serves the needs of all parts of the economy, including the culture, events and creative sectors. Policy could also develop to support creative and events professionals to work internationally and participate in cross-border cultural exchange. Challenges artists now face in touring in the EU after Brexit are a result of the Westminster government refusing to negotiate a mobility framework in the Trade and Cooperation Agreement.

Such an approach could support the sector to attract the skills that it needs from around the world, and help to foster cultural collaboration, learning and partnerships between creative professionals in Scotland and elsewhere in the world. This would help to make the sector more resilient, diverse and vibrant, with positive impacts for communities across Scotland, while helping to promote our culture, events and creative sectors internationally.

Sustaining our communities

The contribution which migrants make to economic growth, innovation and research in Scotland is crucial. However, migrants should not be seen just as workers. Their contribution to the communities in which they live, and to wider Scottish society and culture is significant and must also be recognised.

Scotland greatly values the enormous contribution that is made to our country by people from all over the world. As set out in the earlier prospectus paper on Citizenship,[63] the people of Scotland shape Scottish society by actively participating in it – through deciding to live, to study, to work and to raise families here. This reflects the nature of the country Scotland wants to be – an open country, an inclusive community and a nation that values everyone who makes their home here.

Scotland also has a long history of welcoming refugees who have been forced to seek a place of safety. Over successive generations, refugee communities have contributed to our society, bringing skills and knowledge as well as their culture, heritage and resilience. For the last decade Scotland has set a clear framework for supporting refugees and people seeking asylum, from the day they arrive, through the partnership approach of the New Scots refugee integration strategy. Scotland will continue to work to support people in need of protection for as long as Scotland needs to be their home or as long as they choose it.

Within Scotland, many of our rural and island communities face specific challenges. Population growth is uneven across communities and many local authority areas, particularly those which include Scotland's islands, are expected to experience population decline over the next 25 years.[64] This pattern of distribution, and the depopulation trends in rural and island areas means that the value of migrants to these areas is more than the skills they bring to gaps in the labour market. Their presence in rural areas not only contributes to the demographic and economic sustainability of these regions, but also nurtures the culture of these communities, enabling them to thrive. In some rural areas, the presence of new families coming in is a crucial factor in maintaining key services, like schools.

The Scottish Government values the contribution of everyone who has chosen to make Scotland their home – people who have brought their families with them or who have chosen to start their families in Scotland; children who have never lived anywhere other than Scotland. These individuals are part of our communities.

Contact

There is a problem

Thanks for your feedback