Building a New Scotland: A stronger economy with independence

This paper sets out the Scottish Government’s proposals for the economy of an independent Scotland. It explains what these proposals would mean for you, for businesses, and for Scotland as a whole. It is the third in the 'Building a New Scotland' series, focusing on independence.

Currency and fiscal policy

Key points

This section sets out our proposal for the arrangements for managing Scotland’s economy through a new macroeconomic framework designed to provide stability and the flexibility to respond to changing economic conditions.

With independence, powers currently reserved to Westminster covering monetary and fiscal policy and financial stability, and wider regulation of the economy, will be the responsibility of the Scottish Parliament.

Currency and financial stability

We propose that, on independence, Scotland would continue to use the pound sterling for a period before moving to our policy of adopting a Scottish pound. The change would take place as soon as practicable through a careful, managed and responsible transition, guided by criteria and economic conditions rather than a fixed timetable.

While Scotland is still using sterling, many aspects of monetary policy would continue to be set by the Bank of England. However, an independent Scottish Central Bank would be established with oversight of monetary and economic conditions in Scotland and with responsibility for financial stability.

The Scottish Central Bank would also report on the economic criteria and conditions for moving to a Scottish pound. This would be part of a wider process, drawing on independent advice to inform the decision by the Scottish Parliament on when to introduce the Scottish pound.

Following a vote for independence, Scotland would remain part of the UK while the terms of independence are negotiated. During this period, arrangements would be put in place to enable financial services and products to operate in the same way following independence as they do now. This would maintain confidence and financial stability.

An early priority following a vote for independence would be for the Scottish Government to work with the Scottish Central Bank to design an institutional model and a future approach to financial regulation that would be proportionate to the size and ambition of the financial services sector in an independent Scotland.

Fiscal policy

Our fiscal policy would be designed to support improved economic competitiveness and resilience, underpinned by the principle of fiscal sustainability.

We would set out clear fiscal rules, for example on public sector borrowing, and arrangements for their independent assessment by the Scottish Fiscal Commission.

We would take a responsible approach to servicing a share of UK debt and the sustainable management of offshore revenues.

A robust institutional framework would be established to support the fiscal strategy, with an expanded role for the Scottish Fiscal Commission and a new Debt Management Office.

Of course, as in any independent country, the macroeconomic framework would evolve over time to adapt to changing economic circumstances. Independence means that future decisions and choices will be for the Scottish Parliament and Government to make.

The macroeconomic framework

With independence, responsibility for monetary policy, fiscal policy and financial stability, as well as the regulation of the economy, will transfer from Westminster to the Scottish Parliament.

In this section, we set out proposals for a new macroeconomic framework in Scotland designed to improve competitiveness and economic resilience.

A macroeconomic framework typically consists of three interdependent elements: monetary policy, fiscal policy and arrangements for financial system stability.[97] Monetary and fiscal policy are explained in Box 5 below.

The framework currently in place in Scotland is set by Westminster. The institutions that support its management, including the Bank of England, financial services regulators, and the Office for Budget Responsibility are established in law, but the performance and degree of stability, or otherwise, in the present macroeconomic system is driven by policy decisions made by the Westminster Government.[98]

With independence, Scotland will have responsibility for our own macroeconomic framework and for the operation of supporting fiscal institutions. We would expand existing fiscal institutions, such as the Scottish Fiscal Commission and Revenue Scotland. We would also set up essential new ones, like a Scottish Central Bank and a Debt Management Office, with clear remits and strong governance structures, accountable to the Scottish Parliament.

Box 5: What are monetary policy and fiscal policy?

Monetary policy covers the management of the money supply, credit and interest rates in an economy. It influences the value of goods and services produced in an economy and the value of currency. The monetary policy tools available to an independent Scotland would depend on the choice of currency and the details of the currency regime. How monetary policy is conducted affects prices, business and consumer confidence, investment, trade flows, the cost of public and private borrowing, financial prosperity and wealth.

Fiscal policy covers the use of tax and spending to fund public services, and public investment, for example in transport and other infrastructure.

Effective management of the public finances is a critical requirement for all countries.

Decisions on tax, spending and borrowing must be balanced to ensure a sustainable fiscal position. A clear strategy and robust governance contribute to credibility, predictability and transparency. Fiscal policy plays an important role in stabilising the economy over the economic cycle. Fiscal sustainability is a pre-condition for a successful monetary policy and the credibility of the policy is reflected in financial markets in the cost of borrowing.

The stabilising function of fiscal policy takes two forms. The first is automatic, operating without further government intervention: when, for example, tax revenues move in line with economic growth. The second is discretionary and takes place when policy decisions are made: for example, spending pledges or tax changes in order to respond to the economic cycle, to support particular groups within society and to deliver wider policy objectives.

A stable financial system is essential to the smooth functioning of the economy.

The financial system of an independent Scotland would be regulated to ensure financial stability and to protect consumers, while also recognising the importance of international competitiveness and the need for regulation to be proportionate to the size and complexity of the industry in Scotland.

The role of currency

Box 6: Why currency matters

Currency matters to all of us. The public, business, markets and investors must all have confidence in the currency in order to hold, invest and use it, and must have trust in the wider financial system. It is therefore essential that people, businesses, investors and trading partners recognise and accept a country’s currency.

The choice and operation of a currency has an impact on banking and the wider financial system. It affects prices, business and consumer confidence, investment, trade flows, the cost of public and private borrowing and government debt, financial prosperity and wealth. Ultimately it affects the competitiveness and performance of the economy.

Currency in modern economies is not backed by gold or tied directly to reserves.[99] Citizens use money for transactions and to store wealth through savings investments such as pensions. The external value of the currency – what it buys in other countries – is important for consumers, for businesses trading internationally, and for people holding or investing in assets abroad.

For example, as the value of sterling goes up and down, relative to other currencies, the relative cost – the purchasing power – changes. This is driven by markets, economic fundamentals and expectations.

For all these reasons, confidence in the currency is essential. It is dependent on strong institutional arrangements to support its operation and is an integral part of the macroeconomic framework and performance of a country’s economy.

Among successful independent countries there is no single approach to the currency regime. The choice of currency is a product of economic and financial history and political decision-making.[100]

For example, Austria, Belgium, Ireland, Finland and the Netherlands share a currency – the euro – while Denmark, Iceland, Norway, Sweden and Switzerland have their own currencies.

However, Denmark pegs its currency to the euro (meaning that it shared a fixed exchange rate with the euro) and shares it with Greenland and the Faroe Islands.[101] The decision to peg to the euro is a policy choice: Denmark’s main trading market is the European Union, so pegging provides price stability for trade with the 18 euro economies.

All of those countries, regardless of currency choice, have higher national incomes per head than the UK:[102] a number of different currency arrangements can be seen to support prosperous economies within Europe.

Countries have a policy choice whether to fix the external values of their currencies or allow exchange rates to move freely in response to market forces. The choice has implications for how an economy adjusts to shocks, the monetary policy tools available, and the need for foreign exchange reserves.

With a fixed exchange rate, the country’s central bank maintains a predictable value for the currency. With a floating exchange rate, the value of the currency is determined by financial markets, though monetary policy and interest rate decisions can be used to influence the exchange rate.

The currency of an independent Scotland

As an independent country, Scotland would have options for its currency regime and the underpinning macroeconomic framework.[103]

At the highest level, the options are to:

- share a currency (for example, to continue to use sterling, or join another currency, like the euro), or

- introduce a new currency, a Scottish pound

Each would require different institutional arrangements with different monetary policy tools to manage the economy, and each has different implications for fiscal policy and financial regulation.

We propose two phases for currency policy after independence.

In phase one, from independence day, Scotland would continue to use the pound sterling.

This does not require any formal agreement with the Westminster Government. Sterling has been the legal currency in Scotland for centuries and is internationally traded.

The continued use of sterling would allow time for new institutions, including an independent Scottish Central Bank, to be established during transition and to build credibility, ensuring continuity for citizens and business during the phase immediately after independence.

In phase two, a new independent Scottish pound would be established.

This would take place as soon as practicable through a careful and managed transition. The decision about when the economic conditions are right would ultimately be for the Scottish Parliament. Part of the remit of the post-independence Scottish Central Bank would include advising on these economic conditions. In phase two, the role of the Scottish Central Bank would expand.

The continued use of pound sterling

Our currency proposition is grounded in practicality for households and businesses.

Businesses would continue to trade in pound sterling, with contracts, wages and savings continuing on that basis. For example, arrangements for pensions, deposit accounts, and contracts would all remain in place but be governed by Scottish institutions. Existing private and business contracts in sterling would continue as before. The Scottish Central Bank would be given a legal mandate for financial stability: it would independently oversee regulation of the banking and financial system in Scotland.

During this period regulation for financial services would align with existing regulation and all existing consumer protection would remain in place. However, oversight of regulation would be for the Scottish Central Bank. This would include ensuring all existing regulatory requirements and standards are met, and that the financial sector continues to operate efficiently. The existing deposit insurance guarantee[104] and pension protections would continue. Continued alignment of regulatory structures would be the responsibility of the Scottish Parliament.

Under our proposals, there would be no change in the currency in which wages and salaries are paid or savings and investments made. Financial services and products would remain denominated in sterling. Monetary policy during this period would also continue to be set by the Bank of England.

This would place a greater emphasis on the use of fiscal policy to ensure the overall strength of the economy, and on fiscal sustainability to provide confidence to financial markets. The principles that we propose should underpin Scottish fiscal policy are set out later in this publication.

Key requirements for continued use of the pound sterling

One We would use the time between a vote for independence and day one of independence to put in place all the requirements for continued use of sterling

On day one of independence, the Scottish Government would have legal and regulatory responsibility for the macroeconomic regime in an independent Scotland.

The key operational requirements for day one would be to have created the new institutions and the necessary functions to ensure financial stability.

The Scottish Government would work with UK regulators to ensure a coordinated and clear process.

Alongside this, on independence the Scottish Government would have full control of fiscal policy, further discussed below, and we would ensure sufficiency of sterling reserves to cover this initial phase.

Two We would establish a Scottish Central Bank, to be in operation from day one of independence

The main new institution to be established would be a Scottish Central Bank. It would operate independently of Government and be given a clear mandate, initially focusing on ensuring financial stability.[105]

Further institutional capacity would be required for the development of financial regulation functions and for fiscal policy. We propose a new framework that is credible and comparable in scale and scope to those of similar economies.[106]

Scotland’s current institutional framework is significantly different from that in 2014: new institutions such as the Scottish Fiscal Commission, Revenue Scotland and the Scottish National Investment Bank are already established and operating, with the Scottish Government already performing Exchequer functions for devolved powers and spending.

The Scottish Central Bank would:

- act as banker to the Scottish Government

- assess and report on macroeconomic conditions and macroeconomic outlook in Scotland

- oversee regulatory structures. It would have responsibility for the regulation of financial services, consumer protection, prudential regulation, resolution regimes (to minimise the impact of any bank failures on depositors and the financial system) and the frameworks required to ensure continued operation of the financial system in Scotland, including cooperation with other regulators[107]

- ensure systems are in place to enable financial transactions and the smooth operation of the financial system, including liaison with Bank of England and other central banks.

The Scottish Central Bank would also act as a lender of last resort, where necessary, to the financial system in Scotland in line with current UK practice.

As part of its financial stability role, the Scottish Central Bank would also ensure that deposit guarantees are in place. The current UK guarantee ensures bank deposits are covered up to £85,000 per account, which, in the event of a bank becoming insolvent, is guaranteed by the Government, but then funded by the financial sector through a levy.[108]

Scottish banks would also be able to use commercial payment services for transactions in sterling and other currencies.

Three We would put in place the necessary level of sterling reserves for day one of independence

Scotland would not require foreign exchange reserves for market interventions when continuing to use sterling. It would require reserves for functions related to the Scottish Central Bank’s role of maintaining financial confidence and the stability of the system.

The Scottish banking sector has changed significantly since the financial crisis in 2008-09. There is now a smaller domestic banking sector with many of the major banks operating in Scotland as part of larger UK and international groups.[109] The level of sterling reserves that an independent Scotland would require for day-to-day central bank operations would be proportionate to the size of the sector and in line with the regulatory requirements for the sector. The financial services sector as a whole is discussed in Box 7 below.

There have also been changes to how banks are regulated. For example, they are no longer required to hold assets in relation to a fraction of their deposits, and instead are required to maintain regulatory capital to ensure they can absorb any losses in terms of their commercial and household loans.

The Scottish Central Bank would be required, given existing financial regulations, to govern the level of capital required by commercial banks to be held as reserves and, in doing so, would follow the international capital framework standards on capital requirements of commercial banks (known as Basel II).

Box 7: Financial services in an independent Scotland

The financial services industry contributes substantially to the Scottish economy and to our prosperity.

As well as providing the essential products and services that businesses and citizens use every day, it is a means to save and invest for the future, and to start and operate a business. It also provides protection for when things go wrong. Nearly all adults in Scotland are consumers of financial services.

The sector is also a substantial employer and exporter. Maintaining stability and continuity for consumers, businesses and institutions would therefore be a key priority following a vote for independence.

In the event of a vote for independence, Scotland would remain part of the UK while the terms of independence are negotiated. During this time, all financial services and products would continue to operate and be regulated in the same way as now:

- regulation for financial services would align with current regulation

- existing consumer protection would remain in place (including deposit and pension protection schemes)

- financial products and services would remain denominated in sterling.

As Scotland prepares for independence, we would:

- put in place the foundations to transfer responsibility for the laws and institutions regulating the financial system from the UK Parliament to the Scottish Parliament, and to meet the requirements of EU membership

- put in place the necessary cooperation and regulatory requirements to ensure the continued operation of the financial services industry here in Scotland, as well as facilitating trade with the UK, EU and internationally.

There are a range of choices and models available to an independent Scotland in building a regulatory and supervisory framework for financial services.

The Scottish Government, working closely with the industry and consumer groups, would put in place a model that works best for the needs of Scotland’s economy and people, balancing our ambition for a growing, thriving and international financial services sector with the importance of serving local communities, protecting consumers, and safeguarding the financial system for the long-term.[110]

As the model is designed and placed on a statutory footing, responsibility for the regulation of financial services will sit with the Scottish Central Bank, including:

- consumer protection, covering all financial services and products currently regulated by the Financial Conduct Authority

- authorisation and supervision of all firms and individuals including enforcement and countering financial crime

- prudential regulation of deposit-taking firms, insurers and investment firms and establishment of a Financial Services Deposit Guarantee Scheme

- payment systems regulation and financial market infrastructure supervision

- the establishment of a resolution regime

- general oversight of regulatory structures, including pensions regulations.

Four We would ensure regular reporting on the operation of the use of sterling to provide confidence to investors

Regular reporting on the operation of the system would be put in place to give investors the information they need to have the confidence to invest in Scotland. This would be informed by a range of statistics similar to those currently produced by the Bank of England for the UK, alongside the production of national accounts and balance of payments statistics.[111]

A managed transition to a Scottish pound

We propose to establish a Scottish pound – the policy objective of the current Scottish Government – as soon as practicable through a careful, managed and responsible transition. The decision about when to do this would be taken by the Scottish Parliament, guided by transparent criteria and economic conditions, rather than a fixed timetable.

Decisions about the Scottish pound would also be made by the elected government and parliament at that time. Those would include the precise form of the currency regime for a Scottish pound – for example, a fixed or floating exchange rate – informed by analysis and advice from the Scottish Central Bank.

Key requirements for establishing the Scottish pound

One A Scottish pound would be established when an independent Scottish Parliament chooses to do so

We propose that three broad requirements should inform the introduction of a Scottish pound:

- that the institutional structure – the key fiscal, financial and monetary institutions – is in place and can be extended to take on additional functions to support the introduction of a Scottish pound

- that there is market confidence and credibility in the macroeconomic framework to support a transition

- that change is in the economic interests of Scotland, and meets the macroeconomic objectives of improved competitiveness and enhanced economic resilience.

We also propose three criteria for the transition to a Scottish pound:

- that the Scottish Central Bank has established its credibility. The phase of continued use of sterling would allow time for new institutions to be created and for these institutions to establish a track record

- that foreign exchange reserves and sterling reserves are sufficient

- that Scotland is fiscally sustainable.

In addition, rigorous analysis of trends in trade and investment patterns, the performance of the economy and the needs of Scottish residents and businesses should all inform the decision on when the transition to a Scottish pound takes place.

Two The remit of the Scottish Central Bank would expand on the introduction of the Scottish pound

On the introduction of the Scottish pound, the role of the Scottish Central Bank would expand to take on full control over monetary policy and financial stability. At this point, it is anticipated that the Bank’s mandate would also reflect national policy priorities such as sustainability.

The Bank’s precise functions would depend on the choice of how the currency is operated: for example, whether a fixed or floating exchange rate. In the case of the former, the Scottish Central Bank would operate the exchange rate policy to fit its mandate. In the case of the latter, the Scottish Central Bank would adjust interest rates and use other tools to influence the supply of money and credit in the economy.

Three Scotland would ensure foreign exchange reserves are in place and borrow to secure additional reserves

Countries have varying levels of reserves relative to the size of their economies, depending upon their currency arrangements (see Table 2 for information on the currencies and reserves of the comparator countries set out in the first publication of the Building a New Scotland series).

An independent Scotland’s starting level of reserves would be for negotiation with the Westminster Government. Scotland’s population share of the UKs, foreign exchange gross reserves of $171 billion[112] would be around $14 billion. Borrowing would be used to secure additional reserves.

Borrowing is a normal part of government activity for all major advanced economies. Running a deficit is not unusual. All but two of the 35 IMF Advanced Economies ran a deficit in 2021, including the UK.[113] An independent Scotland would have the full borrowing powers available to other countries to secure reserves.

Further detail on the arrangements that Scotland would need to support government borrowing and the operation of government finances is set out below. The terms of any borrowing would be influenced by the fiscal position, by governance arrangements and by the outlook for the economy.

| Country | Currency | Shared Currency or Own Currency | Fixed or Floating Currency | GDP ($ billion) Current USD |

Foreign Currency Reserves ($ billion) Current USD |

Foreign Currency Reserves as % GDP |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Austria | Euro | Shared | Floating | 477 | 34 | 7.1% |

| Belgium | Euro | Shared | Floating | 600 | 42 | 7.0% |

| Denmark | Danish Krone | Shared[114] | Fixed (Euro) | 397 | 82 | 20.7% |

| Finland | Euro | Shared | Floating | 299 | 17 | 5.6% |

| Iceland | Icelandic Króna | Own | Floating | 25 | 7 | 27.8% |

| Ireland | Euro | Shared | Floating | 499 | 13 | 2.7% |

| Netherlands | Euro | Shared | Floating | 1002 | 64 | 6.4% |

| Norway | Norwegian Krone | Own | Floating | 482 | 84 | 17.5% |

| Sweden | Swedish Krona | Own | Floating | 627 | 62 | 9.9% |

| Switzerland | Swiss Franc | Shared[115] | Floating | 813 | 1110 | 136.5% |

| UK | Pound Sterling | Shared[116] | Floating | 3019 | 194 | 6.4% |

Source: Total reserves (includes gold, current US$) | Data (worldbank.org)[117]

Four The Scottish pound would be Scotland’s legal currency, but people would still be able to use sterling or other currencies

The Scottish pound would be introduced in a clear, transparent and planned way with the Scottish Central Bank working with the financial sector in Scotland. Introducing a Scottish pound would make it legal tender within Scotland for the banking sector and for government, citizens and businesses. For example, it would be the unit of account for Government with contracts, wages, benefits and taxes all denoted in that currency.

The introduction of the Scottish pound would not prevent sterling, or other currencies, from being used. That would be open to individuals and businesses.

Many existing financial contracts will continue to be denominated in pounds sterling and individuals would continue to have a choice regarding what currency they hold their money in or transact in terms of business. The process of exchange from sterling to the Scottish pound would be voluntary and reflect the preferences and requirements of individuals, as well as the provisions available via the banking and wider financial services sector in Scotland.

Decisions about the currency that applies to new contracts, products and services, as well as the option to switch existing contracts, would therefore be for individual providers and consumers.

Fiscal policy as part of the UK

Key points

As part of the UK, estimates set out in Government Expenditure and Revenue Scotland 2021-22[118] show that expenditure for Scotland exceeds total revenues, with expenditure standing at £97.5 bn in 2021-22 and total revenues (including North Sea revenues) standing at £73.8 bn. In 2021-22, therefore, Scottish revenue was sufficient to cover all devolved day-to-day services, all social security, including state pensions, and public sector pensions.

An independent Scotland would take on responsibility for other areas of expenditure that are currently reserved, such as defence, investment, and repaying the national debt. Were Scottish spend in these areas to be broadly similar to existing UK spend, Scotland would have a fiscal deficit, as the UK does.

In response to the challenges of rising inflation and interest rates in 2022-23, the Scottish Government is taking measures to live within its means and protect the vulnerable across our devolved responsibilities. The actions we are currently taking in our devolved capacity demonstrate the government’s preparedness to take the steps necessary to safeguard fiscal sustainability.

As set out in more detail below, the UK is also in deficit and has been for most of the past 50 years. It is also true that in the financial year ending (FYE) March 2021 every country and region of the UK ran a net fiscal deficit. London, the South East and the East of England moved into net fiscal deficit in FYE March 2021, after being in net fiscal surplus in FYE March 2020.[119]

Accumulated deficits mean that the UK has a large public sector debt. Scotland's opening fiscal position would reflect, to some extent, the UK's previous fiscal decisions, and the division of UK assets and liabilities would be agreed as part of negotiations with the UK Government.

Given the uncertainty over the outlook for the global, UK, and Scottish economies, and future fiscal and economic policy decisions by the UK and Scottish governments prior to independence, this publication does not present an estimate of the starting fiscal position of an independent Scotland. However, the Institute for Fiscal Studies has considered the position under the current constitutional arrangements and suggested that, in 2022-23, the Scottish deficit could match or be smaller than the UK deficit.[120]

The Scottish Government’s powers are constrained by the current constitutional arrangements. On independence, Scottish governments would have full powers over both fiscal policy, and economic policies which could play a key role in boosting tax revenues. This would allow them to take decisions which ensured that Scotland is fiscally sustainable, while prioritising support for public services and investment, and rejecting the ‘austerity’ approaches imposed on Scotland by UK Governments in the recent past.

The limitations of the current constitutional arrangements

Under current constitutional arrangements, the Scottish Government has a total budget of £56.5 billion (in 2022/23). The Scottish Government has control over a limited range of taxes which together are forecast to raise over 30% of the total budget in 2022/23.[121], [122]

The Scottish Government has used these powers to address Scottish priorities, through a distinctive approach to taxation,[123] establishing a more progressive system while ensuring that it balances the budget on an annual basis.

However, under the current constitutional settlement, the Scottish Government also faces substantial constraints.

Even with recent devolution of powers relating to Income Tax (partially devolved), Land and Buildings Transaction Tax and Landfill Tax, the funding from the ‘Block Grant’[124] still accounts for about 65% of the Scottish Budget on average.[125] This means that the funding available to the Scottish Government is largely decided by others, increasing or decreasing to reflect changes in Westminster Government spending in line with its policies in comparable areas to those devolved to Scotland.

Significant spending responsibilities remain reserved to Westminster, as do a range of revenue raising activities such as tax including Corporation Tax, value-added tax (VAT), National Insurance and fuel, alcohol and vehicle excise duties.

The Westminster Government also retains control over a range of policy areas which influence tax receipts, such as those over immigration, energy and trade policy. The limitations of the current fiscal arrangements have been particularly apparent during the COVID-19 and cost of living crisis.

When other governments have borrowed to fund vital support for businesses and households, the Scottish Government has had to rely on the Westminster Government deciding whether it would undertake additional spending. While some decisions ultimately resulted in additional resources flowing to the devolved nations’ governments via the Barnett formula, the need to await Westminster Government announcements on the scale and timing of these funding flows created uncertainty and delay when flexibility and responsiveness was needed most.

And our ability to spend on Scotland’s priorities is being further affected by the Westminster Government’s use of powers provided by the UK Internal Market Act 2020 (IMA).

This enables the Westminster Government to spend directly on activity that is devolved, depriving the Scottish Government and Parliament of funding that would have otherwise been available for our programmes and services.

There are also no guarantees that the Barnett formula will continue to be applied in future. Ultimately, the Scottish Parliament’s funding is controlled from Westminster.

The current fiscal context

Scotland is one of the wealthiest parts of the UK, with the highest GDP per capita of any of the UK’s nations or regions, other than London and the South East.[126]

This section outlines Scotland’s fiscal position under the status quo and in the context of the UK’s fiscal position.

The UK has consistently run a deficit since 2000-01, and in most of the last 50 years has borrowed more than 3% of GDP per year.[127]

Even before the pandemic, the UK had one of the largest deficits in Europe, and during the pandemic it ran the second largest deficit amongst advanced economies, with the deficit reaching almost 15% of GDP.[128] Although the UK deficit has begun to fall, it is forecast to remain above pre-pandemic levels until at least 2023-24.[129]

Within current UK constitutional arrangements, any limited borrowing undertaken by the devolved governments as part of their fiscal frameworks is reported in that aggregate UK borrowing figure.

Like the rest of the UK, Scotland is recovering from the impact of the pandemic, which has had a significant impact on public finances.

The overall estimated position based on the current constitutional arrangement is one of budget deficit as estimated expenditure exceeds revenues. Figure 6 shows estimates for the contribution that devolved taxes, reserved taxes, devolved spending, and reserved spending[130] have each made to the implied overall fiscal position for Scotland over the last 5 years.[131]

Source: Government Expenditure and Revenue Scotland 2021-22 Government Expenditure & Revenue Scotland (GERS) 2021-22 – gov.scot (www.gov.scot)

With independence, the fiscal outlook for Scotland would be determined by policy decisions and the performance of the Scottish economy.[132]

We set out later in this document a vision for the economy in an independent Scotland, a vision that reflects among other things the importance of population growth and labour force participation.

The opportunities available to an independent Scotland

On day one of independence, the Scottish Government would have full autonomy to take decisions over tax, spending and borrowing to meet Scottish needs, supported by key fiscal institutions and the necessary governance framework.

The government of an independent Scotland would also have the power to issue its own sovereign debt[133] and have the full range of powers necessary to set fiscal limits, undertake investment, and support the management of the Scottish economy.

It would be the responsibility of the Scottish Government to demonstrate both to the citizens of Scotland and to financial markets and lenders that the approach would be sustainable, to establish its creditworthiness and minimise borrowing costs.

The first publication in the Building a New Scotland series set out how small, advanced economies generally pursue policies of more prudently managed debt and deficits than larger countries.

Taking a fiscally sustainable approach is fundamental for any country – indeed, it is a necessary foundation of the fairer country we seek to build – and would be particularly important for a newly independent country. It would be crucial in:

- establishing the credibility of the macroeconomic framework and minimising the interest rate at which Scotland can borrow, ensuring it could invest effectively. Fiscal credibility and sustainability are discussed further in Box 8 below.

- ensuring that Scotland would have sound public finances, and demonstrating to the world that we have the conditions necessary to be a high-performing market economy, ready to participate and compete in global markets, and to re-join the EU.

The framework proposed in this document is underpinned by the following assumptions:

- that Scotland aspires to become an independent member of the EU

- our proposals for Scotland’s currency are implemented

- that fiscal policy needs to be carefully balanced and act in support of, rather than against, economic performance.

Box 8: Fiscal credibility and sustainability

Fiscal credibility means that people believe that a government will do what it says with regards to its fiscal policy.

It makes the economic environment more predictable, allowing firms and individuals to plan and to take decisions with confidence. It increases the confidence of those lending to the government, which, all else being equal, results in a higher credit rating and lower borrowing costs for all.

A credible fiscal framework is central to ensuring the public finances remain on a sustainable path over the medium term and support the performance of the economy.[134] This is also essential to the wellbeing of the country overall.

In periods of economic growth, higher tax revenues and lower spending on measures such as unemployment support can allow governments to strengthen their fiscal position and increase headroom against fiscal rules. Meanwhile, in periods of weaker economic performance, fiscal policy can be tailored to support the needs of individuals and businesses through more challenging times.

Establishing fiscal credibility enables a government to show discretion and use fiscal policy to respond to economic circumstances, for example by allowing spending through automatic stabilisers,[135] like unemployment benefits, to operate in an economic downturn, without damaging confidence in the long-run fiscal position.

A government can establish fiscal credibility in a number of ways:

- setting fiscal policy that is sustainable in the medium term and consistent with the government’s other policy objectives

- building a track record of consistently sticking to plans rather than regularly deviating from them

- demonstrating political commitment to fiscal sustainability through fiscal targets, either in law or via published medium term policy frameworks

- ensuring independent fiscal institutions, such as the Office for Budget Responsibility operating at the UK level and the Scottish Fiscal Commission operating at Scotland level, to hold governments to account and enhance fiscal credibility and improve fiscal performance[136]

- establishing a strong framework governing fiscal policy decision-making, external scrutiny of forecasts and budget decisions, and sound fiscal management via independent debt management institutions.

Fiscal rules enhance credibility: they are an important feature of credible and coherent fiscal policy.[137]

Without rules, fiscal policy may suffer from deficit bias, where countries run looser fiscal positions on average (e.g. pursuing policies that increase the deficit) than would be optimal for fiscal sustainability. Governments therefore use fiscal rules to commit themselves to responsible management of the public finances and so increase confidence among taxpayers and investors.

There are four broad types of fiscal rules: budget balance rules,[138] debt rules,[139] expenditure rules[140] and revenue rules.[141]

Budget balance and debt rules are most common, especially amongst small, advanced economies and sub-national governments. Since 1990 almost every member country of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) has adopted some sort of fiscal rule.[142]

Of European comparator countries to Scotland, all have a budget balance rule and the majority have a debt rule. Revenue rules are uncommon (see Table 3).

| Country | Expenditure Rule | Revenue Rule | Budget Balance Rule | Debt Rule |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Austria | Yes | No | Yes | Yes |

| Belgium | Yes | No | Yes | Yes |

| Denmark | Yes | No | Yes | Yes |

| Finland | Yes | No | Yes | Yes |

| Iceland | No | No | Yes | Yes |

| Ireland | Yes | No | Yes | Yes |

| Netherlands | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Norway | No | No | Yes | No |

| Sweden | Yes | No | Yes | Yes |

| Switzerland | No | No | Yes | No |

| UK | No | No | Yes | Yes |

Source: IMF Fiscal Rules Database

Existing fiscal rules were designed to achieve low debt levels in an economic environment with positive, but moderate, interest rates, keeping the cost of debt servicing low.

COVID-19 has changed the fiscal landscape for most advanced economies, and high debt levels and low – but rising – interest rates are now common.

The EU Stability and Growth Pact, which sets the fiscal rules for EU countries, is currently suspended to allow member states to respond to the impact of COVID-19 and ongoing geo-political challenges.

Key requirements for Scottish fiscal policy

One The Scottish Government would establish fiscal rules informed by international best practice

Setting credible and responsible fiscal rules, and demonstrating that there is a plan in place to meet them, is essential to ensuring market confidence in a newly independent Scotland. Having that market confidence, and sustainable public finances, is necessary if we are to build an economy that combines dynamism with fairness.

The decision on fiscal rules, and on the strategy for meeting them, would be for a future Scottish Government.

We would set fiscal rules designed to put public finances on a sustainable path. The rules would ensure that day-to-day spending was kept within fiscally sustainable limits, and debt kept at sustainable levels, but would still permit the government of an independent Scotland to properly support public services and borrow to invest. The UK experience of recent years has shown that an ‘austerity’ approach to achieving fiscal sustainability, in addition to damaging people and services, also harms the economy and so is counterproductive.[143] We reject such an approach.

Developments that would inform the precise fiscal rules the Scottish Government would set include:

- the future form of the EU Stability and Growth Pact. This effectively sets out the fiscal rules for EU member states. The expectation is that the Pact may in future be more flexible, giving more weight to the need for strategic investment and the investment required, for example for a just transition to net zero.[144] We would propose, for the period before Scotland re-joins the EU, fiscal rules that were, as far as possible, aligned with the principles and the approach of any future EU Stability and Growth Pact. Meeting existing Stability and Growth Pact criteria is not a precondition for joining the EU

- the starting fiscal position of Scotland. No estimate of the fiscal starting position is set out in this document, given the uncertainty over the outlook for the global, UK, and Scottish economies, and future fiscal and economic policy decisions by the UK and Scottish governments prior to independence

- developments in the global economy, including international trends in fiscal rules.

The Scottish Government would, as a first step, set a transitional rule for the size of the current deficit for the early years of an independent Scotland. This would require that current borrowing be kept within certain limits over the economic cycle, while enabling and encouraging investment in long-term priorities for Scotland, of the kind proposed for the Building a New Scotland Fund.

We would set out the proposed fiscal rule in advance of Scotland becoming independent, to allow it to be scrutinised and understood in advance of it coming into effect.

Setting this initial rule would provide time to consider, in detail, the fiscal position inherited from the UK, international best practice in setting rules for future years and the introduction of a broader suite of rules of the type outlined in the box above.

This broader suite of rules would include a debt rule. The position for Public Sector Net Debt (PSND)[145] would be determined by the outcome of negotiations with the Westminster Government on assets and liabilities, and a ‘solidarity payment’, which we explain below.

A target would be set once a sustainable level and trajectory for PSND was clearer. The right timescale would depend on the precise nature of the rules set by the government of the day as well as the economic and fiscal context of the time.

Performance against the suite of rules would be assessed annually by the Scottish Fiscal Commission, and the rules would be reviewed, and re-set if necessary, at least once every five years. This would be done with a view to ensuring fiscal sustainability and taking into account any requirements set by the EU.

It would be for the government of an independent Scotland to set out a clear pathway to ensuring overall fiscal sustainability and that fiscal targets are met.

Independence presents an opportunity for Scotland to adopt a different economic policy to the UK, and it is through economic growth that Scotland would aim to achieve fiscal sustainability. Increased growth and productivity, including through access to international markets and an immigration policy tailored to Scotland’s needs, would in turn increase tax revenues for the Scottish Exchequer.

In addition, we would kick-start an independent Scottish economy though significant infrastructure investment on the government's key priorities in the early years of Independence. We set out details of the Building a New Scotland Fund later in this publication.

Governments in an independent Scotland would also consider, as all governments do, the appropriate balance of tax and spend as part of an overall fiscal strategy whilst ensuring that decisions were right for the economic conditions of the time.

Two The Scottish Government would establish a robust institutional framework to support Scotland’s fiscal strategy

Under current constitutional arrangements, fiscal rules are set by HM Treasury for the UK as a whole, and key fiscal institutions – those that make forecasts or issue debt – operate at the UK level.

In an independent Scotland we would establish institutions that suited Scotland’s needs, including those set out below, alongside an expansion in the economic and finance ministry functions of the Scottish Government:

Expansion of the role of the Scottish Fiscal Commission

The Scottish Parliament established the independent Scottish Fiscal Commission (SFC) in 2016, following the passage of the Scottish Fiscal Commission Act 2016, to advise on and scrutinise Scotland’s public finances. The SFC currently produces independent forecasts of growth, devolved tax revenues and devolved social security expenditure to feed the Budget process.

The OECD’s Independent Fiscal Institutions Review[146] praised the SFC’s “many positive results in the two years since its creation [2017-19], building good relationships with stakeholders and a reputation for independent and credible forecasts, and improving the fiscal policy debate in Scotland.”

We propose that, under independence, the Scottish Government would enhance the SFC’s capacity to provide robust, credible forecasts for Scotland and to provide independent analysis of progress toward Scotland’s fiscal targets. This would build on work already under way by the SFC to publish their first fiscal sustainability report in 2023.[147]

Establishment of a Debt Management Office

We propose also to set up a Debt Management Office (DMO). In line with best practice,[148] this would be sponsored from within the Scottish Government’s Exchequer function, but it would have a high degree of autonomy and operational independence.

The Scottish Government would carefully manage the transition from the UK Cash Management system[149] to an independent DMO, to ensure that new and existing cash requirements are met. The process and timing for establishing the Scottish DMO and flexibility within the fiscal framework to deliver this would be subject to negotiation with the Westminster Government.

In order to manage the cash requirements from day one of independence, the Scottish DMO would need to be established and operating cash management facilities well in advance, and the Scottish Central Bank would need accumulated reserves to support the activities of the DMO. The reserves needed to meet the Scottish Government’s cash requirements, alongside the Central Bank’s currency reserves, would sit outside of the fiscal rules set out above.

The DMO would be tasked with meeting the financing requirements for government and aiming to minimise the government’s borrowing costs. It would manage the debt stock, the issuance of debt, local government debt, and contingent liabilities.

Its responsibilities could be extended over time to include the efficient and effective management of the government’s portfolio of assets and liabilities, to help improve capital allocation and contribute to an improved fiscal position.

Three The Scottish Government would pay a reasonable share of the servicing of the net balance of UK debt and assets to demonstrate our creditworthiness

The starting position for an independent Scotland is that it would not inherit any of the UK’s debt stock, as HM Treasury set out in 2014.[150]

However, the Scottish Government also recognises that Scotland, in a spirit of co-operation and responsibility, should service a fair share of UK debt and is committed to doing so via an annual ‘solidarity payment’, following negotiation.

Following independence, Scotland would take on the full range of powers over tax and spending and be able to issue its own debt. But the price that Scotland paid to borrow would be determined in financial markets, and financial investors would value Scottish debt according to how much they trust Scotland to repay it.

The Institute for Government[151] expects the ‘solidarity payment’ to help to reduce any ‘new country’ premium on its debt and minimise any borrowing premium relative to other countries. It would also contribute to a positive and respectful relationship with the Westminster Government to support a period of orderly transition, and provide a basis for positive negotiations around the apportionment of UK assets.

There would need to be negotiation between the two governments on the appropriate level and structure of contribution, based on a detailed assessment of UK assets and liabilities.

The Scottish Government would undertake further analysis of UK assets and liabilities in advance of a negotiation with the Westminster Government.

Four The Scottish Government would normally use windfalls, such as from oil and gas taxation, to invest for long-term benefit (such as the net zero transition) or hold in reserve for use in exceptional circumstances

Recent global events illustrate the difficulty in predicting receipts from oil and gas.

As noted in the second publication in the Building a New Scotland series Renewing Democracy through Independence, successive Westminster Governments have not stewarded energy resources, particularly oil and gas reserves, to deliver long-term, structural benefits for the economy. It notes that the Institute for Public Policy Research has estimated that:

“If a fund had been created from the North Sea oil revenues in the 1980s, it would be worth over £500 billion [in 2018].[152]

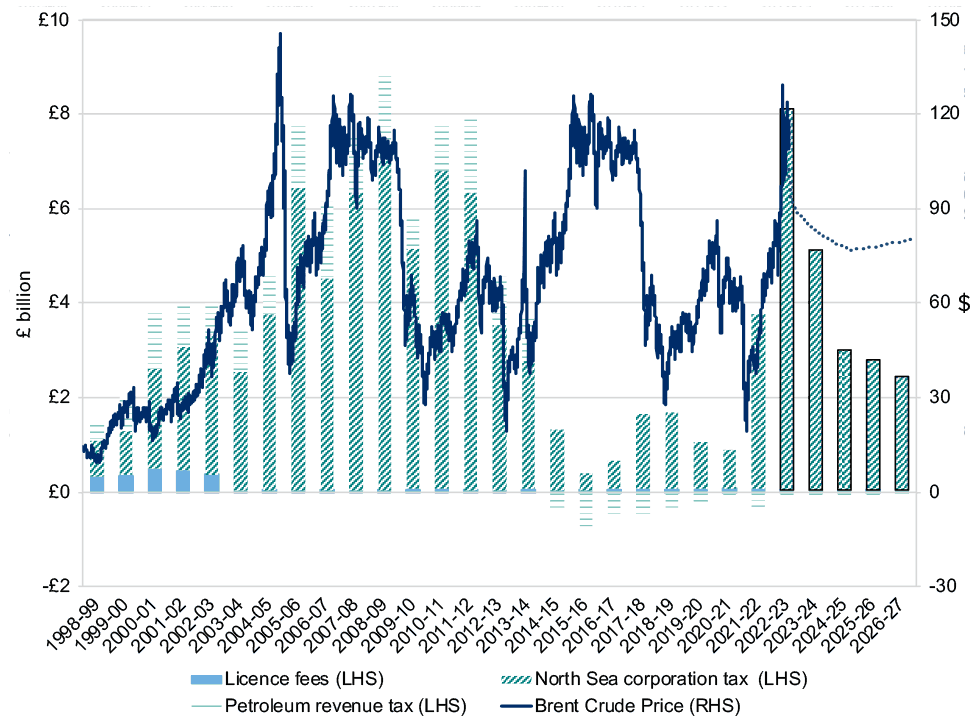

The revenue from the North Sea has had a varied, but positive, impact on Scotland’s implied net fiscal position over the last 20 years, as shown in Figure 8.

Over the last five years, revenue has averaged around £1.5 billion a year, although receipts have been variable.

In recent years revenue from oil and gas has been low by historical standards. Between 2000-01 and 2012-13 North Sea revenue contributed to Scotland’s estimated fiscal position by on average 6% of GDP a year, with the largest impact (8.1%) in 2008-09.[153]

The recent increase in oil prices has led to a significant increase in UK revenue from the North Sea, rising from £0.5 billion in 2020-21 to £3.2 billion in 2021-22.[154] Revenue is forecast to rise further in 2022-23.

However, North Sea revenue is affected by several factors beyond just the oil price. In 2012-13 and 2013-14, tax revenue fell while the oil price remained elevated, reflecting falling production, rising operating costs, and increased capital investment, all of which acted to reduce companies’ tax liabilities. Figure 7 compares North Sea revenue and the oil price since 1998-99.

Source: Outturn from Government Expenditure and Revenue Scotland 2021-22 Government Expenditure & Revenue Scotland (GERS) 2021-22 – gov.scot (www.gov.scot) Forecast, Scottish Government calculations based on OBR’s March Economic and Fiscal Forecast Economic and fiscal outlook – March 2022 – Office for Budget Responsibility (obr.uk)

This is likely to impact directly on the outlook for the Scottish fiscal position, reflecting the fact that oil and gas receipts are a more important source of revenue for Scotland than for the UK as a whole.[155]

Sources: Figures from 1998-99 from Government Expenditure and Revenue Scotland 2021-22 Government Expenditure & Revenue Scotland (GERS) 2021-22. Earlier figures are experimental statistics from: Historical Fiscal Balances 2014 (nrscotland.gov.uk); UK figures consistent with OBR Public Finances Databank August 2022 Data - Office for Budget Responsibility (obr.uk).

In January 2022, before the recent increases in the outlook for North Sea revenue, the Economics Observatory forecast that – under the current constitutional arrangements – the implied Scottish deficit in 2022-23 could be 8.8% of GDP.[156]

North Sea revenue is now expected to be around £10 billion higher than when the forecast was made, both as a result of the increase in oil prices and the new Energy Profits Levy, whose planned introduction this year is forecast to raise an additional c.£5bn in 2022-23. This could see the implied fiscal deficit fall further, with the Institute for Fiscal Studies suggesting that the Scottish deficit could match, or be smaller than, the UK deficit in 2022-23.[157]

Figure 9 below, illustrates how the Economics Observatory’s January forecast could change given the latest outlook for North Sea revenue, with the deficit falling to below 3% of GDP in 2022-23. With the changing economic outlook since the beginning of the year, and the additional support for household and business energy bills, the UK and Scottish deficit are now expected to ultimately be larger than shown below, although the relative position may remain unchanged.[158]

Source: Economics Observatory and Scottish Government calculations What might the public finances of an independent Scotland look like? – Economics Observatory

At the point of independence, there would be a choice to be made about the use of oil and gas revenues and other windfall income. Revenue forecasts do not currently extend beyond 2026-27, but the North Sea Transition Authority forecasts that production will decline by about 7% a year every year longer term, so we would expect this to depress revenue in future years even if prices remained high. The decline in production will be driven by the maturing of the UK Continental Shelf as well as domestic and international climate change commitments.

This suggests that the peak of the forecast revenues, while still making a significant contribution, would have passed before an independent Scotland began to make its own fiscal policy.

North Sea oil and gas revenues, along with other windfall income, could be used to reduce the level of borrowing required to service the deficit that the Scottish Government is likely to face as it leaves the UK.

However, the Scottish Government believes that in normal times revenues generated from oil and gas taxation, together with other windfall income, should be separated from day-to-day resource spending, and used to invest for the long-term benefit of the Scottish people.

This approach would support sustainable fiscal policy by avoiding predicating current spending and tax policy decisions on potentially volatile oil and gas output and revenues, whilst demonstrating the Scottish Governments commitment to investing in the Scottish economy.

This is our proposed Building a New Scotland Fund.

Contact

There is a problem

Thanks for your feedback