The challenge of population balance: mapping Scotland's institutional and intervention landscape

A report by the independent Expert Advisory Group on Migration and Population exploring Scotland's institutional and policy landscape with regards to population.

Chapter 1: Policy landscape

In this chapter we attempt to map out the policy landscape, by picking out, and providing a basic description of, policy activities which in some way affect or respond to population change. As explained in the Introduction, it is not easy to draw precise boundaries to this landscape, but our goal is to sketch out its main features. These are predominantly public sector led activities, mostly under the direct or indirect control of the Scottish or UK governments, but also driven by local councils and agencies, which have significant interaction with population trends, whether as cause or response, mitigative or adaptive, explicit or implicit. Third sector organisations and private businesses are often involved in the delivery of such policies.

Mapping the policy landscape is a first step, a necessary foundation for describing (in Chapter 2) the network of key players in the institutional system engaged in the process of delivery in relation to the Scottish Government’s overarching goal of balanced population change. This in turn provides the basis for a more in-depth consideration of objectives and intermediate outcomes, from a Theory of Change perspective, in Chapter 3.

The material presented in this chapter has been assembled through a desk-based review of policy documents and webpages. It is important to acknowledge that such an approach to policy mapping has its limitations. A more in-depth and nuanced discussion would require primary research (interviews with key actors). It is hoped that this deficiency may be addressed in a subsequent EAG report.

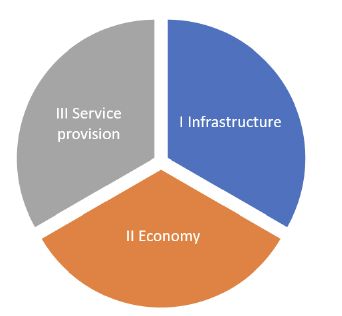

This chapter is structured according to a pragmatic 3-fold classification of policies which address or respond to population balance (Fig 3). The three types of policy are:

I. Those which address built infrastructural needs.

II. Those which focus mainly upon the economy.

III. Those which are concerned with basic services.

No claims of theoretical or conceptual profundity are made about this classification. There are, of course overlaps between the categories, and many interventions could be placed in more than one of them. It is simply a device for organising the discussion.

Pilot actions under the ADAP do not fall exclusively within any of the above three types, (although they perhaps contribute most strongly to the third) and will be introduced briefly at the end of the chapter.

I Infrastructure

Infrastructure is here conceived as encompassing both transport networks and other physical capital, in other words, policies which deal with the built environment. Whilst the Scottish Government has an overall responsibility to establish guiding principles and has set up a range of national schemes to address particular issues or themes, much of the detailed local activity or oversight falls to the 32 Councils. This explains the prominence of a number of Scottish Government strategy documents designed to disseminate priorities and improve coherence.

National Infrastructure Plan (NIsP)

The National Infrastructure Plan (2021-26) underpins a number of ‘frontline’ policies, in this case by coordinating and prioritising capital expenditure by the Scottish Government. Published in 2021, the most recent policy document predates an awareness of forecasts of future population decline, although it does acknowledge the issue of ageing, and that even within the assumed context of continued growth overall, some parts of Scotland faced population decline (p17-18). The response to these demographic challenges is wrapped up in a commitment to “build resilient and sustainable places”. It is understandable (given the underpinning nature of the NIsP), that the document provides few clues as to how this will be achieved in practice, instead citing more frontline policies, such as the Islands Plan, and City Region Deals (see below).

National Transport Strategy

Scotland’s Second National Transport Strategy (2019) acknowledges that the particular challenges and costs of getting around, to and from, some rural and island areas, can drive the outmigration of young people (p18), and that “transport can have an adverse impact on the long-term sustainability of island communities” (p19).

In terms of policy response to these challenges, the Strategy states (p47) that it will “adopt targeted approaches that align with local needs” which will “ensure those living in rural, remote or island communities will be well connected and have as equitable access to services as those living in the rest of the country, therefore making a positive contribution to maintaining and growing the populations in these areas.” Further detail on how this will be achieved is not provided, except for references to the National Islands Plan.

Housing to 2040 Strategy

This overarching housing strategy document, published in 2021, clearly acknowledges the role of housing supply in both driving and ameliorating rural and island depopulation (p27), promising (p9) to “take specific action to support housing development in these areas, helping to stem rural depopulation and supporting communities to thrive.” Targeted interventions include the Affordable Housing Supply Programme, and the Rural and Island Housing Fund. A number of specific actions (relating to tenure, land availability, construction standards and so on) are also proposed (p29, p59).

National Planning Framework (NPF4)

The Fourth National Planning Framework (NPF4) document outlines a spatial plan for Scotland and sets out the principles which are to be followed by the planning departments of the 32 councils responsible for development at a local level.

The spatial plan is orientated around six “overarching spatial principles” (p4):

1. Just transition.

2. Conserving and recycling assets.

3. Local living.

4. Compact urban growth.

5. Rebalanced development.

6. Rural revitalisation.

Clearly the last two are very closely related to the “balanced population” goal of the Population Strategy. The concept of rebalanced development is envisaged in terms of revitalising declining industrial areas, fostering new rural activities based upon renewables, and more generally facilitating dispersed economic activity and the wellbeing economy (p16). The vision for rural revitalisation features dispersed activity and globalisation of rural supply chains through improved connectivity (p16). The importance of balanced population development is underlined in the Regional Spatial priorities of the National Spatial Strategy (p20-35), where issues of either depopulation or ‘overheating’ are mentioned in all four of the regional profiles. In the context of the development of the National Spatial Strategy a number of councils have produced Indicative Regional Spatial Strategies (IRSS) for their areas. Several of these highlight issues relating to population balance. The Argyll and Bute IRSS, for example, states “The major overriding issue for the area is depopulation which needs to be tackled by: i) enabling community wealth building to grow resilience in our communities, creating higher quality jobs and enabling new investment in our communities, ii) delivering a diverse range of new homes, and iii) by improving our connectivity both in terms of transport and digital connectivity.” The IRSSs for South of Scotland, Highland, and Shetland all underline the planning system’s awareness of the issue of population balance.

A key element of the National Planning Policy, which is the subject of Part 2 of the NPF4 document, is the requirement for planning authorities in the 32 councils to produce Local Development Plans (LDPs), in consultation with local communities. Balanced population change plays a key role here too: “Greater constraint will be applied in areas of pressure whilst in rural areas with fragile communities, a more enabling approach has been taken to support communities to be sustainable and thrive. LDPs are required to set out an appropriate approach to development in areas of pressure and decline informed by an understanding of population change and settlement characteristics and how these have changed over time as well as an understanding of the local circumstances including housing and travel” (p18).

The development of an LDP is a substantial commitment, taking place on a ten-year revision cycle. Many of the local plans in force were developed under previous guidelines. It has therefore not been possible to carry out a review (as for LOIPS p14 below). However, it will be interesting to see whether the LDPs are equally as effective in promoting balance in depopulating and in overheating areas. Apart from the relatively passive effects of land use zoning, the regulatory levers available to planning authorities are arguably better suited to mitigating overheating than to stimulating repopulation or retention.

II Economy

Policies in this category seek to promote economic growth in the regions and cities of Scotland. Modifying population trends is sometimes an explicit motivation for such activity. This policy area has the added complexity that in addition to the 32 councils, it involves public sector agencies established by the Scottish Government, and the third sector. It also features interventions initiated and co-funded by the UK government.

The National Islands Plan

The National Islands Plan, established in 2019, following the Islands Act of 2018, is a five-year integrated strategy which seeks to address the particular challenges faced by Scotland’s 93 inhabited islands. We consider it first in this section because its place in the population policy landscape is firmly and unambiguously established by its first Strategic Objective: “To address population decline and ensure a healthy, balanced population profile” (Scottish Government 2019 p3, 18-20). The primacy of this objective is a response to a long-established concern about the drift of population from many of the islands, its effect upon age structure, wider implications for economic activity, the sustainability of service provision, and community viability. It is also tightly interdependent with the 11 strategic objectives which follow. These address issues of economic development, transport, housing, fuel poverty, digital connectivity, health, social care and wellbeing, environment, climate change, community, culture and education. The implementation of the Plan is documented in a “Route Map” for 2020-25, and annual progress reports.

The Development Agencies

Scotland has three (regional) development agencies. The oldest, dating back to the 1960s, covers the North and West, and is known today as Highlands and Islands Enterprise (HIE). The most recently established, South of Scotland Enterprise (SOSE), covers the mostly rural areas between the central belt and the English border, whilst Scottish Enterprise focuses on the rest of Scotland. The challenge of population decline in rural and island areas was very much the founding rationale for the Highlands and Islands agency (Copus 2018). Still today it lists “a more balanced population and growing skilled workforce” as the first of its key outcomes. The South of Scotland agency’s vision statement is founded on the need to tackle depopulation: “We will be a region of opportunity and innovation - where natural capital drives green growth, ambition and quality of life rivals the best in the UK, communities are empowered and cultural identity is cherished, enabling those already here to thrive and attracting a new generation to live, work, visit, learn and invest in the South of Scotland.” One of the six themes which describe its response to this challenge (p36) states its ambition “to be attractive, competitive and to showcase the best of the region – essential if we are to address population decline. To succeed in this, we need to make the South of Scotland exceptional, emphasising quality of life, connectivity, amenity and vibrant neighbourhoods.”

Regional Economic Partnerships

Regional Economic Partnerships (REPs) are key elements of the Scottish Government’s Economic Strategy. They take the form of agreements between the Economic Development Directorate of the Scottish Government and a range of regional economic interests, including councils, community organisations and bodies representing private sector business. Although several of the REPs originated as UK Government-initiated City Region Deals, with ‘trickle down’ concepts in their DNA (Copus et al 2022), the Scottish Government’s 2015 Economic Strategy framed their goals in terms of inclusive growth. More recently, in its 2022 National Strategy for Economic Transformation , the emphasis was shifted to the promotion of a wellbeing economy.

The REPs and City Region Deals are mentioned in Scotland’s Population Strategy document (Scottish Government 2021, p70) as a policy element contributing to the balanced population objective. The presumed link between regional economic development and population patterns and trends is all too often taken for granted. In reality, the connection depends upon the nature of the development, particularly the scale of employment creation, its sustainability, and spatial distribution.

Whether the REPs can be considered a significant element of the population policy landscape requires careful consideration of the implications of the evolution of goals between the 2015 and 2022 economic strategies. Although it has obvious attractions in terms of ethos, inclusive growth is a tricky concept to tie down in practical terms. The official definition (Inclusive growth what does it look like? Scottish Government 2022 p36): “growth that combines increased prosperity with greater equity; that creates opportunities for all; and distributes the dividends of increased prosperity fairly” shares with the Population Strategy its strong emphasis upon regional/local ‘balance’. However, it is clearly expressed in terms of economic outcomes, and assumes growth. The 2022 Strategy with its sights set on wellbeing, implies that outcomes are not measured simply in economic terms, but also in more qualitative social aspects, and environmental sustainability. Whilst the 2015 Strategy’s pursuit of inclusive (economic) growth implies some potential for collateral mitigation of population trends, the shift to wellbeing economy objectives seem to suggest a tacit acknowledgement that adaptation to demographic trends is an acceptable outcome. The links between the objectives of the REPs and the pursuit of “balanced population” are thus quite indirect and contingent on a range of contextual issues.

Community land ownership and community development initiatives

Scotland’s community land ownership and community development interventions do not fit neatly or exclusively into one of our three broad policy types. Arguably some of them straddle all three. However, we consider them here since the way in which they affect population trends is essentially by opening-up new economic opportunities, often community-based, rather than private sector, both in the countryside, and through urban regeneration.

The legal framework is provided by several pieces of land reform legislation, from 2003 onwards[6]. A new Land Reform Act is currently being debated in the Scottish Parliament. Whilst land reform is not officially advocated in policy documents as a direct vehicle for promoting balanced population7, it is important to mention it here, because it is widely assumed to be the gateway to community development initiatives (urban as well as rural) which play a very important role in regenerating the local economy, and thereby improving population retention.

III Service Delivery

The third group of policies is concerned with what is often referred to in a European context as “services of general interest” (SGI). This term covers a wide range of activities, spread across the public, private and third sectors. For obvious reasons policy is most developed in relation to those services which are customarily delivered by the public sector, such as education, health and social care, public transport, the emergency services, or refuse collection. In recent years there have also been examples of the public sector stepping in to ensure provision of services in “market failure” situations, where commercial providers cannot do so with profit, notably in terms of digital infrastructure.

A comprehensive review of all kinds of SGI is not practicable here. Three key examples are provided, illustrating the way in which the objective of population balance affects the management of school buildings, the provision of health and social care, and the improvement of digital infrastructure.

Community Planning Partnerships

Before focusing in on the three named services, it is important to acknowledge that at least in part, population balance considerations are addressed, in a more holistic way, by the 32 Community Planning Partnerships (CPPs) set up under the Community Empowerment Act of 2015, following a review of local service provision by the Christie Commission, published in 2011.

Readers from outside Scotland, especially those familiar with local governance in other parts of Europe, including those (such as the Nordic countries) in which municipalities have relative freedom to act, over a much broader range of service provision responsibilities, will find the concept of Scotland’s Community Planning system unfamiliar. We will consider the governance issues in greater detail in Chapter 2. At this point it is perhaps sufficient to state that, over the past decade or so, there has been considerable debate about how to ensure that the legacy of relatively centralised service provision arrangements - in which much of the decision making is retained by the Scottish Government whilst responsibility for local delivery is shared between the 32 councils and a range of specialist agencies - can on the one hand be more flexible in its response to different local conditions, and at the same time avoid the disadvantages of uncoordinated policy ‘silos’. It is within this space that we would expect the notion of population balance, as a basis for decisions about service provision, to be worked out in practical terms.

Key elements of the responsibilities of the CPPs are Local Outcome Improvement Plans (LOIPs) covering their area, and at a finer spatial scale, focusing upon places with specific issues and needs, Locality Plans. The Improvement Service, which supports local government in Scotland, carried out an initial review of available LOIPs in 2018 and found them very variable in terms of approach and level of detail. The 2018 review was mainly concerned with the process of local strategy development and says little about thematic focus. In any case, since then most CPP’s have issued revised LOIPs.

The Improvement Service has since explored the manner in which councils are responding to demographic change. Their 2024 report ‘Navigating Demographic Change’ describes Local Outcome Improvement Plans (LOIPs) and Local Development Plans (LDPs) produced by local authorities and their partners as a demonstration of ‘how local authorities are understanding and responding to the challenges posed by demographic change’ (p.7).

The briefing goes on to note that local authority strategies typically combine strategies to both mitigate and adapt to population change and that LOIPs prioritise actions and interventions under a range of relevant themes including housing; employment; reducing inequalities and providing appropriate services to a changing population. However, whilst the report addresses both the second and third objectives of the Population Strategy, the examples provided mostly relate to age structure implications rather than balance. They provide a number of examples of adaptive approaches, gleaned from CPP LOIPS.

Responses to the informal survey of selected councils which carried out as part of this project[7] (Box 1) indicate broadly positive views of LOIPs as an exercise in holistic thinking about population balance as a policy issue, tempered by reservations about the practicalities of implementation.

Box 1: Perspectives on LOIPS provided by respondents to our survey of Councils

Text in italics quotes responses.

Amongst local authority responses to our survey LOIPs were described as a useful tool and one which can provide a focus for and coherence across the activities of a number of partners. However, responses also highlighted the difficulty in turning intentions into outcomes in the face of severe financial constraints.

The LOIP’s can highlight the issues and ensure a more connected and holistic approach to planning and delivering services is adopted, but the actions and outcomes in the LOIP must be achievable within the budgets and resources available.

Local authorities also commented on an uneven focus on population concerns within and across LOIPs. For some, the LOIP was seen as too blunt a tool with neither sufficient resource, nor sufficient nuance to achieve desired local outcomes.

LOIPs are wide in their scope and outcomes. Complementary, localised, coproduced action plans that can be resourced and delivered are more appropriate and likely to get community buy in.

In preparing this report a quick review of all 32 LOIPs, with a view to an impression of how they address population balance, was carried out. LOIP documents vary considerably in length and level of detail. Most are framed as local responses to the agenda set by the Scottish Government, promoting inclusive growth and wellbeing, and tackling various forms of exclusion, poverty, and disadvantage. Many of the plans reflect an extensive programme of public consultation. In many cases, community perceptions of needs and challenges appear to drive the diagnosis, and the selection of themes to be addressed by the LOIP. In other cases, a more traditional review of published statistics allows objective benchmarking against national averages. It must be observed, however that there is little uniformity in the way published statistics are used, making simple comparisons between LOIPs difficult.

Furthermore, whatever the evidence base, it is important to recognise the tricky mismatch between the concept of population balance, which is intrinsically a comparative (between area) concept, and aspatial/societal concepts of exclusion, poverty and disadvantage. The confusion of concepts within the LOIPs is a microcosm of a wider challenge for Scottish population policy, to which we shall return in Chapters 4 and 5.

The diagnostic part of each LOIP report is generally followed by a detailed presentation of policy aspirations. In our quick review it was not always obvious how these aspirations would, in practice be delivered, i.e. in terms of specific, funded, and targeted interventions, or in terms of adjustments to statutory service provision obligations. Where interventions were specified, it was often a repackaging of existing activities of CPP member organisations. From these impressions of the character of the LOIPS it is perhaps judicious to be cautious in assuming that they will effectively address the issue of population balance.

Community Planning Partnership |

||

|---|---|---|

Council Area |

Direct reference in diagnosis to population change/balance |

Direct reference to population change/balance in CPP Aspirations |

Argyll and Bute |

Yes |

No |

Yes |

No |

|

Yes |

No |

|

Yes |

No |

|

Yes |

No |

|

Inverclyde |

Yes |

No |

Yes |

Yes |

|

Yes |

Yes |

|

North Lanarkshire |

Yes |

No |

Yes |

Yes |

|

Yes |

Yes |

|

Yes |

No |

|

Yes |

No |

|

Yes |

No |

|

Yes |

No |

|

Yes |

No |

|

Most of the LOIPs discuss the challenge of ageing as a ubiquitous issue. Just half of Scotland’s 32 CPPs (Table 1) contain within their diagnosis of the key issues facing them an explicit reference to population trends or population balance. However, only four of these address population issues directly in their policy aspirations. Of course, it is arguable that focusing upon inclusion or well-being may indirectly mitigate negative population trends and could also take the form of adaptation to such trends. Nevertheless, it is clear that the LOIPs’ contribution to the three objectives of the Population Strategy is primarily directed at ageing, rather than at population balance.

Specific examples of the way in which population balance is handled by the LOIPs are provided in Box 2.

Box 2: Some examples of how CPP LOIPs address the issue of population balance

The Outer Hebrides CPP LOIP for 2017-27 places a very strong emphasis upon the role of service provision in responding to population change. Its first priority (alongside economic growth and wellbeing) is to “retain and attract people to ensure a sustainable population”. This is to be achieved by increasing housing availability, improving the general attractiveness of the area as a place to live and work, by making young people more aware of local opportunities to deter out-migration, and enhancing digital and transport connectivity. The issue of population balance is thus clearly front and centre of the strategy of the CPP, and mitigation is very much on the agenda.

In the Moray LOIP the challenges associated with population balance relate partly to the presence of armed forces bases, and (as in other areas), to the out-migration of young people. The policy response is incorporated under the heading “Developing a diverse, inclusive and sustainable economy”. It is foreseen to be achieved “through the higher education offer in Moray, alternatives such as apprenticeships, ensuring the right mix and availability of housing and the right environment for people of all ages”.

The LOIP for the Orkney Islands recognises the challenge of balancing population trends in the “Mainland” and “Inner Isles” with those on the “ferry connected” Outer Isles. Locality plans for the latter are in preparation, having the aspiration to “maintain or increase” population. It is anticipated that this will be achieved mainly “through levelling up digital and transport connectivity, widening the availability of services, and improving access to employment opportunities.”

The Refrewshire LOIP, like many others, sees a shrinking working age population as a challenge. However, unlike other CPPs, Renfrewshire is not solely focused on adaptation, (for instance by addressing the exclusion of older people) but takes a more proactive mitigative approach: “Growing our working age population is a key driver to improving our local economy. We need to attract new people to work, live and settle here, but also incentivise our young people and student population to stay here too. In order to do this, we need to make sure that we have the infrastructure in place to support this, such as the right types of housing, good schools and transport links.”

The Dumfries and Galloway LOIP, also places a strong emphasis upon population trends in its diagnosis of the challenges confronting it. However, its strategy is framed more as an adaptive approach, summarised as “working in partnership to ensure a confident, ambitious, healthy and fairer Dumfries and Galloway for everyone who lives and works here.”

School buildings, restructuring and closure.

Provision of schools of appropriate size, and in locations accessible to shifting populations of children, has become a totemic issue both in rural areas with declining population, and in areas where population growth is putting pressure on the capacity of local services. Management of the schools’ estate is a responsibility devolved to the 32 Councils. However, the way in which they carry out this responsibility is circumscribed by statutory guidelines issued in 2015[8]. This document (paragraph 33) makes it very clear that the overarching objective for making changes to the school estate (building, restructuring, closure) must be the educational interests of the pupils, as manifest in an Educational Benefits Statement. However, in the case of rural schools there is a presumption against closure (paragraph 66). Closure or restructuring plans need to consider educational benefits,

community impacts, and the travelling arrangements of pupils. In terms of the likely impact upon the local community, the Council is directed to consider “whether closure of the school will affect the local community’s sustainability and whether the asset of the school’s buildings, facilities and grounds would still be accessible, or lost, to the community. Whilst the quality of educational experience of affected pupils remains the primary consideration, the purpose of this requirement is to ensure that the future of a rural school is also considered in the wider context of rural development planning and the sustainability of rural communities” (paragraph 78). Suggested examples of possible impacts include the changes to local patterns of migration (especially of young families), adjustments to other local services, the loss of the school as a venue for community activities, and associated effects on the local economy.

Health and Social Care

Although local health and social care provision is not infrequently in the news - perhaps because of local opposition to the closure of a rural hospital or other facility, or the difficulty in filling vacancies for doctors or nurses in rural areas – it would also be true to say that there is not a very active popular debate about the role of such issues as drivers of depopulation. At the other extreme, in suburban areas where the population is growing, primary health care services may be overstretched, but this does not seem to reduce the attractiveness of such areas or to dampen growth. Perhaps this is because, unlike school provision, access to health care is not, for the majority of residents or families, a daily issue, and perhaps one that they would rather not anticipate.

Health and social care policy has experienced rapid and profound change over the past decade. This has been driven not only by advances in medical and therapeutic science and technology, but also by policy reforms such as the integration of health and social care delivery (see Chapter 2), and the introduction of a new contract for the General Practitioners (GPs) which deliver primary care. Health and social care are very much bundles of different specialist services, with multiple professional objectives, and subject to a range of performance monitoring.

Local authorities and Health Boards work together to attract and retain a workforce. Furthermore, Integration Authorities have a duty to strategically plan for the health and social care services their population will need in the future. As a needs-based service there is an expectation that individuals who require social work or social care support can access it from the place they live. Thus social care planning functions predominantly for adaptation, rather than mitigation.

A fascinating example of the potential of health and social care provision to nudge local population trends (either positively or negatively) has been provided by one of the responses to our survey of councils, in which a Regional Health Trust embraced the concept of Community Wealth Building as an Anchor Institution. This was presented by the respondent as a means of enhancing the residential attractiveness of the area, i.e. mitigating population decline (Box 3).

Box 3: Community Wealth Building as a mitigative approach to population balance

NHS Ayrshire and Arran published their first Anchor/ Community Wealth Building Strategy in January 2024 in an attempt to address challenges posed by post-Covid recovery, health inequalities, child poverty and the climate emergency. Their strategy aims to reset the local economy to create a region where wealth is shared fairly, enabling people of all ages to live full and healthy lives. This will be achieved by investing and spending locally, creating fair and meaningful employment, designing and managing NHS buildings, land and assets to maximise local and community benefits, and to reduce health services’ environmental impact. NHS Ayrshire and Arran’s ambitions align with North Ayrshire Council’s, facilitating partnership working and in turn through the ambitions of Community Wealth Building, alleviate pressures on the region’s health service, making North Ayrshire a more attractive place to live.

Despite the neglect of health and social care as a means of mitigating population change, there is an awareness of the need to adapt health and social care provision to the differing needs of areas experiencing population change. This is acknowledged by the establishment of a short life working group on GP services in rural and remote areas, which produced a report on implementing the new GP contract in rural areas, and more recently the establishment of a National Centre for Remote and Rural Health and Care. The Scottish Parliament’s Health, Social Care and Sport Committee recently carried out an inquiry into health care in rural Scotland, finding that, in a number of ways, health care policy has not been sensitive enough to needs of such areas.

Provision of digital infrastructure

Digital Scotland’s 2021 Strategy (A Changing Nation: How Scotland will thrive in a digital world) incorporates a range of dimensions, but the first one “no one left behind…” is directly relevant to the Population Strategy. It is the justification for various initiatives (the best known being the R100 scheme) to extend networks to areas where there is insufficient commercial incentive for provision. Although this is presented as motivated by inclusion, the secondary benefits in terms of population balance are clearly acknowledged:

“Our investment in digital infrastructure will ensure that our rural and island communities share fully in the future economic, social and environmental wellbeing of Scotland. It can help to address population decline by making living and working in a rural setting a more attractive option, and put small rural businesses on a level playing field with their competitors by providing ready access to international markets…. As working from home becomes a new normal for many, there will be new opportunities for people to live and work in every part of Scotland and we want to work with remote and rural communities to ensure that they benefit from this trend.” (Digital Scotland p28-9)

The positive population balance benefits of the digital strategy are further affirmed in the text of the mandatory impact assessment under the terms of the Islands Act.

Pilot actions under the Addressing Depopulation Action Plan (ADAP)

Finally, this overview of the landscape of policy which addresses or responds to the issue of population balance acknowledges the role of a range of local authority pilot actions funded by the Scottish Government under the auspices of the 2024 Addressing Depopulation Action Plan (ADAP). The origins of the ADAP, in the ‘repopulation zone’ initiatives developed by the Convention of the Highlands and Islands (COHI) were described in the EAG’s 2022 report Place-based policy approaches to population challenges: Lessons for Scotland. The key characteristics of the repopulation zone initiatives were identified as: being intrinsically place-based, bottom up, led by resettlement officers employed by the local councils, and multisectoral – incorporating actions relating to housing, jobs, critical infrastructure access to public services, talent attraction/retention and return migration. Under the ADAP these initiatives are overseen by an “Addressing Depopulation Delivery Group”, and together with other “pathfinder initiatives”, receive financial support from the Addressing Depopulation Fund. As the term “pathfinder” suggests, these initiatives are very much viewed as learning opportunities; they are being monitored and evaluated in order to identify good practice in different contexts.

At present there are six pathfinder initiatives, five of which are mostly rural in character (Argyll and Bute, Highland, Comhairle Nan Eilean Siar (Western Isles), Dumfries and Galloway, East Ayrshire), and one is urban (Inverclyde). The intervention logic of these six initiatives will be discussed in Chapter 3, but it will perhaps be helpful here to note that several are quite narrow in their focus (housing being the key issue), whilst others, notably that of the Western Isles, are much broader in their approach.

Reflection: Which policies make a difference?

Having scanned the policy landscape and identified a set of policies which claim to address population balance, it would be very satisfying to turn to an evaluation literature which might offer some answers to this question, however tentative. Unfortunately, we are not aware of any attempts to assess what effect these policies have on population balance. Indeed, on reflection, this is perhaps not surprising, since for most of the policies we have identified, population balance is a secondary objective, and it is one consciously shared with other interventions. Impact evaluation of the conventional “value-for-money” sense would clearly be very difficult to apply to any single policy area. In addition, the specification of a counterfactual or “policy-off” comparator would be extremely challenging.

Contact

Email: population@gov.scot

There is a problem

Thanks for your feedback