The challenge of population balance: mapping Scotland's institutional and intervention landscape

A report by the independent Expert Advisory Group on Migration and Population exploring Scotland's institutional and policy landscape with regards to population.

Chapter 2: Institutional map and evolving governance

In this chapter we will attempt to provide a description and explanation of the complex system of governance within which the interventions identified in Chapter 1 are implemented. In keeping with the objective, set out in the Introduction, of communicating this in a manner which is accessible to readers from outside Scotland, it will be helpful to set this in the context of the unique but evolving division of responsibility between UK and Scottish Governments, the 32 councils, various public agencies, regional development partnerships, community and third sector organisations, and the private sector.

Whilst some of this may appear obvious or superficial to readers within Scotland, it seems a useful exercise in standing back and “seeing ourselves as others see us”. It is extremely important, both for the reader outside Scotland, who may be unaware of the somewhat “messy” system, and for the reader who is familiar with just their own corner of the structure, to set population policy within its wider governance context. The interaction of the various moving parts of the “balanced population machine” described in Chapter 1 can only be understood against the backdrop of tensions between different levels in the governance hierarchy.

A simple institutional map of interventions to enhance population balance

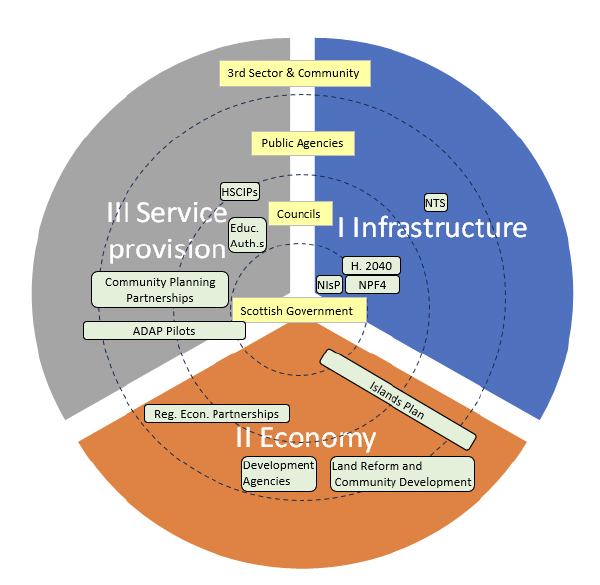

Bearing in mind the three generic types of policy involved in delivering population

Balance, it is possible to cross-reference these with different levels of governance (Fig 4). Most of the ‘actors’ (the pale green boxes) are located within a single “tier” of governance. The main exceptions being the implementation of National Planning Framework (NPF4), the Community Planning Partnerships (CPPs) and the Health and Social Care Integration Partnerships (HSCIPs), which straddle two or more levels in the hierarchy. However, most of these actors are influenced by, and have influence over, the activities of other players within governance system. Unfortunately, in the interests of clarity these interactions cannot be shown in the diagram.

The first of the three types of intervention, relating to infrastructure, is dominated by policies managed by the Scottish Government, although the National Infrastructure Plan (NIsP) and Housing to 2040 (H. 2040) are to a degree implemented at the local level by the councils. The councils act as local delivery agents for the NPF4, under the strategic guidance of the Scottish Government. The National Transport Strategy is delivered by a public agency, Transport Scotland.

The segment of the diagram representing policies concerned with the economy feature public agencies (the Regional Development Agencies) and partnerships (the Regional Economic Partnerships). The Islands Plan is shown as having its “home” within the Scottish Government, although it must be acknowledged that local delivery is very much a collaboration with the relevant Councils, and with 3rd sector or community groups. Similarly, the land reform and community asset purchase process are facilitated by a public agency called the Scottish Land Commission, whilst financial support is provided by the Scottish Land Fund. Land or asset purchase is, however, a gateway to community development opportunities which are heavily dependent upon the third sector.

Key actors in the local development scene (both under the Islands Plan, and in projects facilitated by community asset purchase) are the over 350 local Development Trusts, and their representative body, the Development Trust Association.

In the service provision segment, there is a more complex pattern of partnership working. The Community Planning Partnerships are collaborations at a local level between the councils and various agencies and partnerships. Similarly, the Health and Social Care Integration Partnerships are collaborations between the relevant (regional) health board, and the one of the 32 councils. The education authorities sit within the council level, although they participate in the Community Planning Partnerships.

Because Figure 4 is structured by the policies shown in Figure 3, governance actors which have a more general remit to support the councils such as the Convention of Scottish Local Authorities (COSLA), or the Improvement Service are not shown. The former is a representative body for the councils. In recent years, COSLA has invested considerable staff resource in following and contributing to the Scottish Government’s development of the Population Strategy and ADAP. It is a key player in the Population Roundtable (see below) and is represented at Expert Advisory Group meetings. The Improvement Service is a Scottish Government funded agency, tasked with supporting the councils. In 2024, it published a report describing the range of ways in which councils are addressing population challenges, especially demographic ageing.

Box 4: The views of local authorities on the role of the third sector

In our survey of local authorities, we also asked which third sector organisations they viewed as having a significant role to play in determining population trends. Responses were quite varied, but some local authorities clearly see third sector organisations as important actors in this area.

Views reflect the diversity of the third sector and the kinds of activities and outcomes it can support. Smaller community-based organisations and those focused on sport and leisure have an important role to play in supporting health and wellbeing, combatting isolation and supporting connections, including for newcomers to an area. Those offering clubs and activities for children can offer an important contribution to childcare provision for working parents.

More established and economically focused organisations such as community development trusts or registered social landlords on the other hand may contribute to skills development and employment opportunities as well as developing locally grounded responses to changing housing needs.

On Arran, the third sector is playing an important role in improving workforce sustainability. From January to March 2023, North Ayrshire Council delivered a ‘test of change’ pilot with investment from the Scottish Government Island Skills and Repopulation Pilot. The ‘North Ayrshire Islands Skills Initiative’ (NAISI) provided a dynamic, local response to maximize opportunities and socio-economic benefits, in partnership with relevant stakeholders in order to pilot skills interventions that support island economies and meet local need and demand on the islands of both Arran and Cumbrae, including:

- Providing short-term funded skills and capacity building solutions that ensure islanders are engaged with and participate in activities that meet local needs and employment priorities;

- Identifying priority groups include jobseekers, young people, parents, women, minority groups and individuals who require upskilling/re-skilling to enable and encourage continued employment and/or volunteering by members of the community;

- Supporting skills in childcare and exploring options for increasing available childcare provision on islands; and

- Strengthening links and understanding of need between local, regional and national partner organisations, local schools, colleges, universities, island businesses and organisations and senior phase curriculum options.

As part of this initiative and in recognition of the declining population and workforce on Arran, in February 2023, the Council provided funding to Arran CVS to produce the Arran Skills Initiative Report. The report recognised that the declining population on Arran is having a significant impact on the available workforce, resulting in staff shortages across a range of sectors. Following the conclusion of the pilot, the Council secured funding to appoint an Arran Skills Coordinator for an initial 12 month period to deliver recommendations of the Arran Skills Report, establish an Arran Skills Group and develop a workplan with actions and key performance outcomes.

A diagram such as Figure 4 can illustrate the basic outline of the institutional landscape and can suggest some differences between policy segments. However, it is inevitably limited in the degree to which it can do justice to the complex interrelationships between the actors. Perhaps even more important in the present context, it can only present a snapshot. It cannot do justice to very interesting, and meaningful, shifts and trends in terms of where decisions are made, and where innovation originates. An understanding of these nuances can only be conveyed by a more narrative, qualitative approach.

The evolving governance context: devolution, centralisation, relocalisation and the role of place

The governance context of Scotland is distinguished from most European neighbours by two unique features: (i) the 1999 devolution settlement, and (ii) relatively early (by European standards) local government reforms in pursuit of economic efficiency and scale economies.

The former is crucial to the pursuit of population balance because the majority of policy areas which are relevant to the pursuit of population balance (education, health, housing, planning etc) are devolved, making it a bit easier (in theory) to achieve policy coherence. Regional economic development is also, prima facie, devolved, but the UK Government has nevertheless in recent years taken initiatives north of the Border (for example in the City Regions programme, Freeports, and Levelling Up).

Local government reform was implemented in Scotland in 1975, replacing historic counties and districts with a two-tier arrangement of 10 regions, and 56 districts. Further rationalisation, creating the 32 unitary authorities, or “councils”, that we know today, came in 1996. These reforms were distinctive not only in that they came much earlier than those of many other European countries, but also in that they brought with them a strong degree of centralisation of power. The 32 councils have comparatively little freedom of manoeuvre, they delivered services according to the regulations initially set by the Scottish Office, from 1999 by the Scottish Executive, and from 2011 by the Scottish Government.

Responsibility for emergency services and water supply were transferred from local government to regional public sector agencies at various points in the post-war period. These were gradually amalgamated, giving them all a Scotland-wide remit by 2013[9]. The influence of principles of New Public Management (Lapuente and Van der Walle 2020) was very important in driving these changes. By the first decade of this century Scotland’s governance, like that of the rest of the UK, was distinctive (a)

in having (according to European standards) relatively large local government units (in terms of area and population), (b) in that some of the functions which in neighbouring countries tended to be associated with municipalities, have been transferred to public sector agencies, and (c) in a rather centralised decision-making arrangement.

The key disadvantages of the service provision structure which emerged from this neo-liberal quest for efficiency were: (i) The creation of what are commonly known as ‘policy silos’, in which each aspect of service delivery managed itself independently, with little coordination and ignoring opportunities for synergy. (ii) A tendency for services to be offered across Scotland in a ‘one size fits all’ manner, with few concessions to local characteristics and needs. The risk to local democratic rights and accountability was recognised by the UK Government even before devolution (SPICE 2015) and the concept of Community Planning as a solution to this was picked up by the Scottish Office. Two Community Planning Pilots were carried out before the turn of the century. In 2003, the Devolved Administration enshrined community planning principles in the Local Government in Scotland Act, so that leading Community Planning Partnerships (CPPs) became a duty for councils, and participation a legal obligation for a range of other public sector organisations. In 2011, the Christie Commission on the Future Delivery of Public Services recommended further development of the community planning structure and process. This led to the Community Empowerment Bill of 2014, which formalised the community involvement processes, and created the requirement for every CPP to produce a Local Outcome Improvement Plan (LOIP). The CPPs are a very important element of the governance landscape within which the various policies identified in Chapter 1 seek to improve ‘population balance’, because they are intended to improve both coherence and sensitivity to the different needs and constraints of different parts of Scotland. We explore the issues and challenges associated with this below.

More recently, push-back against centralisation of power from various interest groups favouring stronger local democracy has been recognised by the Scottish Government in a consultative process known as “Democracy Matters”. Furthermore, the 2023 Verity House Agreement, between COSLA and the Scottish Government has established the maxim “local by default, national by agreement”. This represents a radical change in the distribution of decision-making power in Scotland’s local governance. It is probably too early to assess the impact, though the articulation and influence of concepts such as the Place Principle,and Community Wealth Building would suggest that the “relocalisation” of governance is more than a passing phase or superficial window dressing. The former is described as “a more joined-up, collaborative, and participative approach to services, land and buildings, across all sectors within a place”. The latter also has a strong emphasis upon “place”, but this time in an economic context, aiming to retain wealth and benefits within local communities.

It is very interesting to compare Scotland’s local governance journey - from early reform ‘rationalisation’ and centralisation, to some extent at the expense of local democratic control, followed by a turn towards various forms of relocalisation - with the experience of countries (such as the Nordics) where municipalities have retained a greater degree of independence, but where there have also been fierce national debates about municipal reforms and experiments with two-tier regional/municipal arrangements. Similar challenges (in terms of service viability and economic pressures) but different historical legacies and traditions have resulted in very different restructuring responses.

The governance narrative of Scotland’s Population Strategy

Having described the evolving governance backdrop we now consider the specific focus on demographic patterns and change which produced Scotland’s Population Strategy and ADAP.

Concern about population issues, especially depopulation of rural areas, is nothing new, the antecedents of the current Population Strategy could be traced back over decades, if not centuries. However, in governance terms a very significant event was the establishment of the Scottish Government’s Ministerial Population Taskforce in June 2019. Taskforce membership comprises 10-15 cabinet secretaries and ministers (composition varies according to the subject under discussion), representing a very broad spectrum of policy areas. The Taskforce’s Terms of Reference state that its role is “to ensure population supports the needs of communities and sustainable economic growth”. It does this by (a) providing a forum for discussion and prioritisation of population issues at the highest level, and (b) promoting pro-active and coherent policy responses. In so doing, the Taskforce has the ambition to render the impact of population policy “greater than the sum of its parts”.

A number of specific responsibilities are also placed upon the Taskforce, relating to:

- Exploring geographic (West-East, rural, island) shifts in population.

- Investigating implications of population change for the public sector workforce.

- Encouraging EU and international migration into Scotland, including of international students, and skilled workers.

- Identifying “policies of place” which encourage in-migration of families to shrinking communities.

- Ensuring that skills development supports population retention and/or repopulation.

- Developing population-related indicators for the National Performance Framework.

The Taskforce is supported by a Secretariat, and by a Programme Board – whose membership is comprised of senior civil servants from relevant parts of the Scottish Government, together with COSLA, the statistics agency (National Records Scotland), the regional development agencies (HIE, SE, SOSE), Skills Development Scotland, and the tourism agency (Visit Scotland). Another forum for discussion with local government is provided in the form of a quarterly ‘Population Roundtable’ (online) meeting, organised by COSLA and the Scottish Government, to which representatives of all 32 councils are invited.

As described in the EAG’s previous report on Place Based Policy Approaches to Population Challenges, the “top-down” decision to promote coherent population policy, by setting up the Taskforce in 2019, was closely followed by a bottom up “Repopulation Zone” initiative by COHI in 2020. The Convention meets twice a year, facilitated by the Scottish Government, and involves the councils of the Highlands and Islands region, together with its regional development agency HIE.

Responsibility for the repopulation initiative has recently been transferred to the Highlands and Islands Regional Economic Partnership (REP).

As implied by the title the COHI programme was distinctive in targeting a number of bounded geographical ‘zones’ which were considered particularly problematic in terms of population trends. Without wishing to stray into the topic covered by Chapter 3 it will be helpful to note that the activities of the ‘repopulation officers’ employed by the scheme focused upon housing and supporting in-migration. In terms of the narrative of governance of population policy the significance of the COHI initiative is that it served to underline the commitment of the councils and HIE, to repopulation, and provided a means of testing territorial approaches, based upon the diagnoses and expertise by locally embedded public servants.

The next chapter of the narrative is marked by the publication of the Scottish Government’s Population Strategy in 2021. In governance terms, the significance of the strategy was not in creating any new delivery structures, new institutional arrangements, or new policy instruments. Its purpose was to raise awareness of population issues of concern (age structure, balance, longer term decline), to express the ambitions of the Scottish Government in response, to describe the range of ongoing policy commitments, and the actors responsible, and to set out detailed, and in part measurable, commitments for future enhancement, with the goal of increased effectiveness of this complex policy system. Like comparable strategy documents in several EU member states (Dax and Copus 2023), the Strategy seeks to ‘set the tone’ for greater coherence and common purpose across a wide-ranging, and often silo-structured, governance network. In respect to many parts of this policy machine the Scottish Government has direct (statutory) levers through which it can, if it wishes, further its objectives in terms of population balance. However, in the context of the increasing appetite for ‘relocalisation’ of governance noted above, the strategy also acknowledges the value, and capacity for impact, of harnessing local innovation, commitment, and energy.

Finally, the Addressing Depopulation Action Plan of 2024 differs from the Population Strategy in focussing only on areas experiencing population decline. Although like the Strategy it reviews existing interventions, in detail it has a stronger emphasis upon specific interventions. Although many of the 83 ‘actions’ listed at the end of the report are pre-existing commitments, the ADAP goes beyond the Strategy in that it announces a new funding scheme, the Addressing Depopulation Fund, which supports ‘pathfinder’ initiatives by councils. That this funding is channelled through local government reflects a strong emphasis upon ‘bottom up’ and place-based approaches, which is justified by references to Verity House Agreement principles.

Partnerships – the key to coherence and relocalisation, or “clutter”?

CPPs deserve special consideration, because there is a temptation to assume that they make a strong contribution to the pursuit of population balance, by “tweaking” the delivery of key services in order to discourage outmigration from shrinking rural areas and responding to new and anticipated demand in areas which are ‘overheating’. We have already reported that local population trends feature in a number of LOIPs. Considerable time, effort and expense are absorbed by the CPP system. There have been several evaluations of the governance processes involved in running CPPs, identifying issues such as the balance between the Councils (who have a statutory obligation as conveners), and other actors, and the difficulties associated with third sector participation. However, there is so far very little evidence of the extent to which the interventions of participant public sector actors are adjusted in response to priorities identified in LOIPs. Many of the service provision responsibilities are statutory, tightly specified and closely monitored at a national level, and perhaps inevitably, within silos which do not interact. The effectiveness of the CPPs in responding to population balance issues (or any other local priority) must therefore be determined, at least in part, by the availability of funds and capacity to implement interventions which go beyond statutory responsibilities.

These are probably modest in scale in the current straightened public expenditure situation[10].

Another form of partnership which is implemented across Scotland is the Health and Social Care Integration Partnership (HSCIP). Scotland differs from the rest of the UK in that the delivery of Health Care and of Social Care are integrated, under the terms of Public Bodies (Joint Working) (Scotland) Act 2014. However, integration is at a regional level, local delivery is probably perceived by many users as still through independent health and social care components. As in England, Wales and Northern

Ireland, in Scotland health care (both local ‘primary care” and “secondary care” in hospitals and other treatment centres) is provided by 14 regional National Health Service boards, whilst social care (a wide range of mental health services, care for children and the elderly, including “care homes”) is the responsibility of the 32 councils. Across Scotland these services are coordinated by 31[11] umbrella “Health and Social Care Integration Partnerships” (HSCIPs)[14].

The ways in which these HSCIPs take account of, or affect, the balanced population objectives of the Population Strategy probably depend to a large extent upon the statutory guidance which is set for them by the Scottish Government. Both the health service and the care system are extremely complex, with multiple and diverse objectives, priorities, and statutory targets. These seem (understandably) to be exclusively within the primary focus of health and social care, with outcomes measured in terms of treatment timing, medical outcomes, public health indicators and so on. Combining these and producing common goals for local partnerships is already extremely challenging, and it is hardly surprising that it is not yet possible to observe any consideration of secondary impacts of decisions on facilities planning and the “estate” upon local population trends.

However, this should not be taken to imply that there is no awareness of the specific health and social care challenges facing rural and remote areas. In 2022, the Scottish Government announced funding for a National Centre for Remote and Rural Healthcare. This was launched in the summer of 2024. Meanwhile, during the summer of 2023 the Health, Social Care and Sport Committee of the Scottish Parliament carried out a consultation on Healthcare in Remote and Rural Areas, with a view to identifying key priorities for the new centre. The final report of the Committee’s finding is due to be published within the coming months. Meantime, the information office of the Parliament (SPICE) has published a summary of responses to the consultation. Interestingly, very few of the responses focused on health or social care challenges per se, instead highlighting issues, such as recruitment and retention, day to day implications of small team working, national funding formulae, and GP contracts, which they perceive to be drivers of rural depopulation. One respondent summed this up by stating that the NHS Scotland Resource Allocation

Committee formula is “inappropriate for rural communities and fails to recognise the importance of healthcare provision in making communities sustainable and attractive places to live, work and stay in” (SPICE 2023 p8-9). Clearly there is scope for rural healthcare policy, and its funding framework to more explicitly and deliberately address population concerns. The Arran initiative described in Box 3 above provides one example of how this could be approached.

More than a decade ago Campbell Christie wrote “we believe that Scotland’s public service landscape is unduly cluttered and fragmented, and that further streamlining of public service structures is likely to be required” (Christie Report 2011). The CPPs were, of course, already in existence when he wrote, and indeed he made recommendations for improving them. However, their effectiveness in promoting population balance is largely contingent on their capacity to inject “tweaks” into the policy silos within which their members operate. It is understood that discussions involving COSLA and Audit Scotland, and focused on increasing the effectiveness of the CPPs are ongoing.

Turning to HSCIPs, it seems that their flexibility and ability to respond to local challenges has already been judged inadequate, requiring the support of an additional organisation. Again, whether this just adds to the “clutter” will depend on whether the new National Centre can bring about concrete changes in rural and remote health and social care delivery which have a positive effect upon population balance.

Contact

Email: population@gov.scot

There is a problem

Thanks for your feedback