The challenge of population balance: mapping Scotland's institutional and intervention landscape

A report by the independent Expert Advisory Group on Migration and Population exploring Scotland's institutional and policy landscape with regards to population.

Chapter 3: Intervention Logics and Theories of Change

In this chapter, we describe the different ways in which the policies and actors identified in Chapters 1 and 2 are intended to work, how they are expected to deliver an improved balance of population. In the policy evaluation literature this is often referred to as “intervention logic”, whilst in more complex multi-actor situations the term “Theory of Change” (ToC) is sometimes preferred (Annex 1). The attraction of the latter, in the context of the present report, lies not only in the fact that it is usually qualitative in application, but it conveys the idea of actions being driven by a mental picture of an ultimate goal, and a series of stepping stone actions/outcomes which constitute a journey towards that goal. Sometimes (ideally) that journey is described in policy documentation, often it is left implicit, perhaps because it is felt to be obvious, and in such cases it has to be reconstructed on the basis of available evidence. This underlines the fact that ToCs may often share with the psychological notion of ‘theories of mind’ the nature of being something in the subconscious, influencing choices whilst not always being thought through in a rational calculating way.

Previous applications of the ToC approach to policies addressing rural shrinking across Europe suggested that although every context and policy story is unique, it is not difficult to find common elements, and to define generic types (Copus et al. 2020,

Dax and Copus 2022). The generic types of ToC proposed by Dax and Copus (Compensation, Relocalisation, Global Reconnection, and Smart Shrinking) are probably too conceptual to be used in this report, and instead we suggest a set of more contextually grounded ToC types which seem to play a role in the design of Scottish policy to address population balance.

Before we do that, however, it is important to acknowledge the role of the concept of “population balance” which, according to the Population Strategy, is the high-level goal to which the various initiatives described in Chapter 1 should aspire.

What is ‘population balance’?

It is of course important to establish a clear and unambiguous understanding of the concept of “population balance”. The obvious starting point for this is the explanation provided by the Population Strategy itself:

P66: “Our focus in this programme is on population balance and the sustainable distribution of our population in a way that works with the characteristics of our places and local ambitions for change. We recognise that both rapid population growth and depopulation can bring challenges.”

P74: “Ensuring that Scotland’s population is more balanced across the country means exploring the significant structural changes that are needed to support attraction and retention in those areas that are losing people and thereby reduce the pressure on areas dealing with a significant growth in population.”

P8: “Place must be at the centre of the answer to our demographic challenge. The economy, infrastructure, housing and public services are all driven by taking a placebased whole-system approach.”

P6: “The Scottish Government’s aim is to make communities across Scotland attractive places to live, work, bring up families and to move to; so that Scotland’s population profile provides a platform for sustainable and inclusive economic growth and wellbeing.”

The concept of population balance which presented in Scotland’s Population Strategy is thus:

- Essentially spatial – it is about balance between places.

- Relative rather than absolute – (there is no underlying spatial plan or targets), and is not about equalisation, achieving stasis, or restoring or maintaining historic levels of population. Rather it is about moderating extreme or rapid change, either positive or negative.

- Motivated by the inclusion and wellbeing objectives of National Performance Framework. More specifically, it seeks to ameliorate the adjustment costs to providers of public services, and the wellbeing impacts to residents, associated with extreme or rapid local population changes.

However, it is important to be aware that the term “balanced” has in the past not always been used in a way which is compatible with the apparent intentions of the Scottish Strategy. Within a more focused debate about demographic change, especially before the past decade or so, ‘balance’ was sometimes associated with replacement rates of total fertility, or with age structure. However, as Lutz (2008, 2014) points out, replacement fertility rates are now so far beyond the reach of most developed countries, it would be very misleading if the goal of “balanced population” were to imply that the Scottish population could ever be stabilised through positive rates of natural increase. What may instead be technically achievable, at a national level, given a supportive UK political context, is a balance between negative natural change and positive net migration. Even this would be much more difficult at a local level.

The term “balanced” has a history of association with various perspectives on regional and rural development, and its use in Scotland’s Population Strategy document is therefore, for some readers, freighted with a range of implicit nuances.

The most obvious of these are:

- Various notions of balanced spatial development in terms of urban-rural or coreperiphery growth, exemplified by the European Spatial Development Perspective’sconcept of “polycentricity”[12]. Since the ESDP, polycentricity has been consistently advocated by a succession of updates, culminating in Territorial Agenda 2030. The term “balanced regional development” has also featured prominently in a debate about Ireland’s National Spatial Strategy[13] (NSS). Scotland’s population strategy is very far from the explicit spatial planning approach of the ESDP, or Ireland’s NSS, but nevertheless hints at the need to avoid a disproportionate concentration of population and economic activity in the Central Belt, especially in and around Edinburgh, using the term “overheating”.

- The term “balanced regional development” has also been employed by the EU to justify rural development interventions which address the wider needs of remoter rural areas, beyond sectoral support for agriculture.

- The sustainability literature’s concept of a balance between human population and the natural ecosystem – derived from some estimate of ecological or biological “carrying capacity”.

Dax and Copus, in their 2022 review of national population strategies of Germany, France, Italy, Spain and Scotland (Dax and Copus 2022), identified a common shift away from neo-liberal intervention logics, driven by economic development and employment, towards a ‘softer’, more qualitative emphasis upon geographic equalisation human rights and wellbeing, achieved through local development processes, driven by social as well as economic goals. We shall reflect upon the future potential implications of this in Scotland in Chapter 4. Before doing so we will explore in more detail the intervention logics which are associated with the current population balance policy landscape.

ToC Types currently associated with population balance

A full ToC analysis (see Annex 1) traces the pathway of logical steps backwards from the goal, through final outcomes, and intermediate outcomes, linked by interventions, back to the starting point, which is the problem to be solved. Internal and external contexts should also be described. It is neither feasible nor necessary to carry out a full analysis here. Ultimately what distinguishes different ToCs as responses to a common policy challenge (in this case population balance) are the intermediate outcomes, which occupy a central position between a common challenge

(depopulation or overheating) and an assumed final outcome (i.e. balance). The rest of this chapter describes seven ToC narratives which are associated with the various policies featured in Chapter 1.

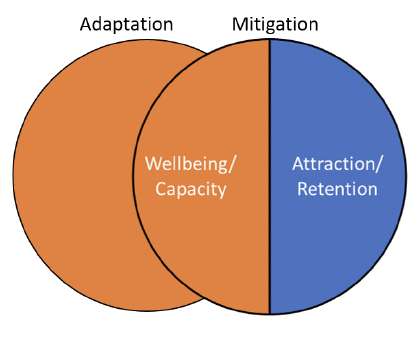

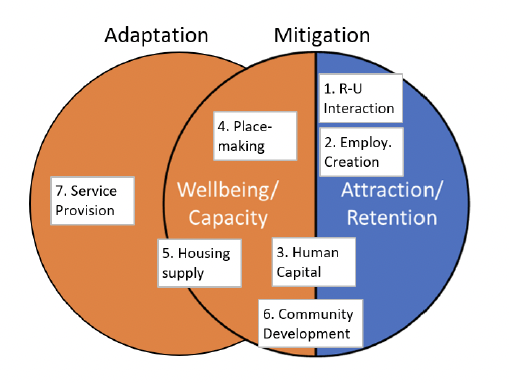

Before describing the individual policy approaches, however, it will be helpful to distinguish two overarching groups (Figure 5). The first of these may be termed “attraction and retention”. These types of approach, as their name implies, act directly upon migration flows. They are by nature mitigative. The other broad group address local wellbeing and service provision capacity, either as an indirect route to mitigation, or as simple adaptation to acknowledged shifts in population distribution.

1. Rural-urban connectedness/interaction. Planners and economists have long assumed that negative population trends in rural areas may be ameliorated by improving accessibility and increased interaction with cities and towns. There is a substantial academic literature which discusses and models such effects (Copus et al. 2022). Various spatial planning approaches, including City Regions, have this ToC as a foundation. In the past ‘key settlements’ have been designated as ‘growth poles’. More neo-liberal versions of this approach have assumed that investing in cities will automatically deliver benefits to rural hinterlands through spontaneous ‘spread effects’.

The Scottish Government’s 2016 Agenda for Cities document summarised this view of regional development as follows: “Good transport connections, affordable housing and local amenities make the regions outside the cities attractive to many city workers, who also enjoy being near to the social and cultural hubs that thrive in cities. Scotland’s cities and their regions gain from their easy access to the varied beauty of rural Scotland and in turn, Scotland’s cities provide a natural home for research and development, education and international connections that support businesses in rural Scotland. When our cities thrive, the rest of Scotland shares the benefit.”

In practical terms this ToC often inspires transport infrastructure improvements, including roads and ferries (as illustrated by the quotation from the National Transport Strategy on p8) and, more recently, installation of faster digital networks.

This intervention logic is very pervasive in regional and rural development circles, and although evidence of effectiveness is mixed, and is rarely challenged despite scattered indications of perverse outcomes sometimes referred to as ‘pump effects’ (Copus et al. 2022). This term describes a situation in which improving access between a major centre and its rural periphery results in the former ‘siphoning off’ economic activity and service provision, and so actually increasing the risk of depletion in the outer rural areas.

2. Local employment creation – On the basis of a review of NPF4 Local

Development Plans and CPP LOIPs, the Improvement Service states (2024 p7) that “Local authorities highlight their role in improving job opportunities through identifying land for business use, supporting key growth sectors and investing in skills and education opportunities”. However, it is questionable whether this activity is driven by a concern for balance, rather than the ubiquitous quest for growth, even in overheating areas.

Both these first two approaches fall into the ‘attraction and retention’ group, and are intrinsically mitigative. However, in both cases the causal links to population balance are somewhat indirect. Economic development is generally assumed to be good for local/regional population trends, but in practise it is a blunt tool - many increases in economic activity bring negligible local employment, and therefore insignificant repopulation.

3. Human capital approaches: This ToC focuses directly upon the age-specific character of rural depopulation. Such approaches thus address both the second (ageing) and third (balance) objectives of the Scottish Government’s Population Strategy. Although they usually have ambitions with respect to mitigation, they may also be adaptive. Neither do they fit exclusively into the ‘attraction and retention’ group, often having wellbeing objectives too.

Several critical points in the population age profile, at which the proclivity to outmigrate peaks[14], form the basis of different human capital approaches.

Perhaps the best-established version of the logic is manifest in the statutory guidelines to education authorities regarding school closure (p14). This builds upon the often-observed cause and effect relationship between school provision and the attractiveness of an area to young migrant families. This applies not only in a rural context, where the closure of a small primary school can have a significant impact upon migration patterns, but also in more densely populated areas, where a secondary school with a strong reputation among parents can affect the housing market within its catchment area. More recently the availability of nursery and preschool childcare has been identified as a key issue in rural areas, leading to various initiatives to ensure provision. Highland Council is, for example, currently carrying out a Rural Childcare Practitioner Feasibility Study as part of their ADAP pathfinder initiative.

A second “pinch point” in the age profile of the population is in the late teens, with the well-known phenomenon of the attraction of young people towards higher/further education, training or employment in Scotland’s cities and university towns. The establishment of the University of the Highlands and Islands was very much an example of a ToC for restoring population balance by retaining young people within their home region.

The third peak in migration is associated with approach of old age, when increasing health and care requirements coincide with mobility (car ownership) issues, to encourage migration into larger villages or regional centres. Awareness of this situation, combined with that for childcare has led Highland Council to explore the feasibility of an innovative “single care model” combining both types of care within a single service.

4. Wellbeing and place-making approaches – This family of intervention logics reflects the assumption that more positive perceptions of the lifestyle and

environmental advantages of areas affected by population decline will lead to increased rates of in-migration. Targeted advertising may be accompanied by

incentives in the form of advice, and even financial assistance with removal costs. These forms of intervention are often combined in a package, with others based on different ToCs; an example being the 2016-18 Argyll and Bute Rural Resettlement Fund, as described in the EAG’s 2020 report on Internal Migration. This ToC falls within the Wellbeing and Capacity Group, and is usually aimed at mitigation rather than adaptation.

5. Addressing housing shortages - The Improvement Service, through their analysis of NPF4 Local Development Plans in their 2024 report, identify housing strategies as a key mitigation approach. It is recognised as a key issue in many parts of Scotland, but in different ways, leading to different policy responses.

In more accessible scenic and coastal areas local housing markets are (as in other parts of the UK) affected by second home ownership and holiday letting, which inflates prices beyond the means of local people. Seasonal occupancy and transient populations change communities and affect the viability of local services. In response, some councils have increased the Council Tax charged on homes which are not permanently occupied. Councils across Scotland are actively developing proposals for visitor levies, which may cover holiday lets. Both the Argyll and Bute and Dumfries and Galloway ADAP pathfinder initiatives are experimenting with a wide range of guidance and advice to increase the availability of privately rented homes for local people, and to discourage the transfer to second home status.

In other areas, often rural, the challenge is the availability of housing of an acceptable quality and size (starter or family homes). There is a close link with employment; business development often being hampered by difficulty recruiting staff due to non-availability of suitable accommodation. The three Community Settlement Officers established by the Convention of the Highlands and Islands Repopulation Zone initiative, and based in Highland, the Western Isles, and Argyll and Bute, provide a range of support and advice relating to housing issues. At a national level the Housing to 2040 Strategy, incorporating the Affordable Housing Supply Programme, and the Rural and Island Housing Fund supports house construction in areas where the stock is insufficient to meet demand. In crofting areas, the Croft House Grant scheme is a long-established response to the need for better rural housing. It “provides grants for crofters to improve and maintain the standards of crofter housing, with the aim of attracting and retaining people within the crofting areas of Scotland”.

Housing supply interventions belong to the ‘wellbeing and capacity’ group, and may be either mitigative or (in the case of overheating areas) adaptive.

6. Community Development - In an international context a very important approach to addressing issues of population balance, over the last couple of decades has been termed ‘endogenous’ or ‘neo-endogenous’ development[15]. The former term is intended to convey the idea that development is locally rooted driven by initiative and capital (physical, financial, human, social and environmental), originating within the locality/community, rather than injected ‘top-down’ by central government. The prefix ‘neo’ reflects the subsequent realisation that ‘bottom up’ initiatives invariably require external inputs of expertise or finance in order to thrive. Within the EU such approaches are exemplified by the various reincarnations of the LEADER programme, and latterly by CLLD (Community Led Local Development). The European Network for Rural Development (now part of the EU CAP Network) has promoted neo-endogenous approaches through the concept of Smart Villages.

In Scotland, because of its distinctive economic, legal and cultural history, particularly the highly skewed distribution of land ownership, community development approaches have often been strongly associated with land reform, and community purchase of land or other assets. In sparsely populated rural areas, without community purchase, the resident population has only a “toehold” in terms of control of local resources. Land for building is (in theory) abundant, but only a tiny proportion is bought and sold on the open market, constraining housebuilding, and business development. The lack of local control extends, of course, to resources associated with the land, such as energy resources, forestry, grazing, fishing and mineral rights and so on. Added complexity, in terms of the cultural implications, comes from the fact that historically (especially before the late nineteenth century) many owners of land in these areas of Scotland viewed the local residents as an encumbrance, rather than an asset, and actively sought to encourage out-migration. It is this backdrop which constitutes a challenging context for neo-endogenous development and explains why state-assisted community land purchase has become a necessary (and headline-grabbing) precursor. The Island of Eigg is often cited as an example (Creaney and Niewiadomski 2016).

Thus, from an international comparative perspective, it is probably correct to see land reform and community asset purchase not as a direct policy response to population decline, but as a (Scotland specific) gateway to processes of neoendogenous development, which are comparable to those observed in mainland Europe, and elsewhere in the developed world.

Community development is very variable in terms of its activities and may fall into either the Attraction/Retention or Wellbeing/Capacity groups. It is usually, though not always, mitigative in its goals.

7. Service provision adjustments – Unlike the preceding ToCs this is predominantly an adaptive response to population change (whether positive or negative). Decisions to adjust service provision levels are usually seen in the (adaptive) context of sound financial management, rather than in the context of population balance. However, as we have seen in the example of school estate above, certain services have become “totemic” and some form of mitigative compromise is sought.

A reflection on impact evaluation

Having delved a bit deeper into the various intervention logics a partial solution to the evaluation conundrum, noted at the end of Chapter 1, presents itself. Each of the ToCs described above has associated “intermediate outcomes”, which are seen as stepping stones on the way to enhancing population balance. These tend to be relatively tangible/measurable and could be taken as surrogates for impact.

However, this implies a strong causal link between intermediate outcomes and final (population balance) impacts, which would need to be tested by objective research.

We will return to this in our recommendations.

Geographic coherence

Policy coherence is customarily conceived in terms of interactions, overlaps and gaps between policy silos. Geographic coherence between locally devolved policy actors is less often considered.

The Improvement Service in their Navigating Demographic Change report (2024 p19) ponder the compatibility of balance with locally devolved policy responsibilities, under the heading “competitive migration”: “Within Scottish local authority plans, population growth, particularly amongst working age groups, features prominently as the means to achieving a thriving economy and sustainability of public services. This is true across local authorities seeking to reverse population decline, but also in areas where the working age population is already growing…If all local authorities across Scotland aim to grow their population through migration, this could create competition between local authorities trying to attract the same people…local authorities should continue to explore where collaborative approaches can maximise benefit across the whole country, building on each area’s strengths…”

Top-down spatial planning approaches have never been favoured in a UK context, nor by the devolved administrations. Within the Scottish policy context the NPF4 National Spatial Strategy arguably could be described as a “light touch” form of spatial planning. It is still in a transitional phase in terms of implementation. Whether within the context of the complex web of statutory and non-statutory responsibilities, the link between NPF4 priorities and those of individual councils (as expressed in their LDPs), will be sufficiently strong to effectively promote “balance” is very difficult to say.

Contact

Email: population@gov.scot

There is a problem

Thanks for your feedback