Heat in Buildings Bill consultation: business and regulatory impact assessment (partial)

Business and regulatory impact assessment (partial) in support of consultation on proposals for a Heat in Buildings Bill.

Context

4.1 The proposals included in the consultation are intended to reduce the contribution of heating buildings to Scotland's greenhouse gas emissions and help achieve ambitious climate change targets set out in legislation.

4.2 The Climate Change (Scotland) Act 2009[4] ("The 2009 Act") (Section 61) sets out a requirement to prepare and publish a plan for the promotion of renewable heat, including a renewable heat target, and to review the plan at least every two years. A new target is now required in order to comply with the 2009 Act's requirement and the proposals included in the Consultation are intended to contribute to this requirement.

4.3 The Climate Change (Emissions Reduction Targets) (Scotland) Act 2019 ("the 2019 Act")[5] increases the ambition of Scotland's targets to reduce greenhouse gas emissions, including a target for net zero greenhouse gas emissions by 2045 and interim targets for reductions of 75% and 90% by 2030 and 2040 respectively. The 2019 Act also includes a range of measures to improve transparency – for example basing progress against targets on actual emissions from all sectors of the Scottish economy. There is a continuing requirement for Scottish Ministers to lay regular "Climate Change Plans" in Parliament setting out their proposals and policies for meeting targets.

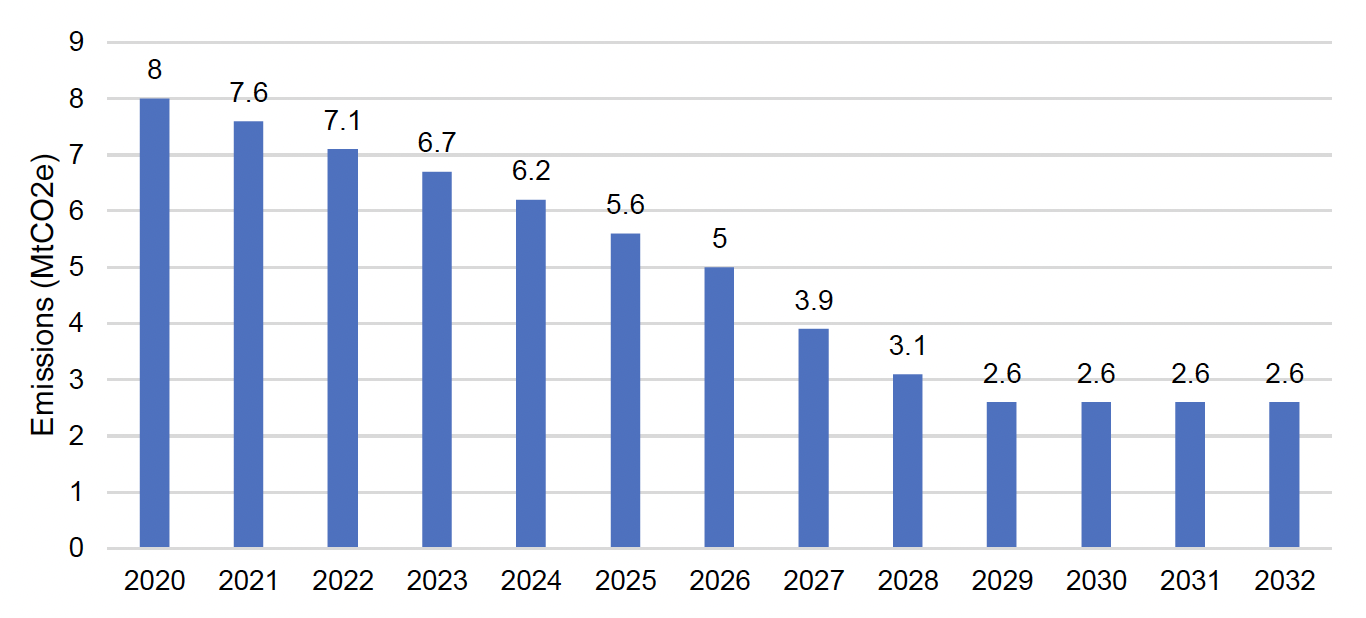

4.4 The provisions in the 2019 Act inform the preparation of a range of Scottish Government strategic documents, including but not limited to, an update to the Climate Change Plan. The Climate Change Plan update sets out the Scottish Government's pathway to our new and ambitious targets set by the Climate Change Act 2019, and is a key strategic document for Scotland's green recovery. It considers the period 2019-2032 and the level of effort that is likely to be required to meet the new 2032 greenhouse gas emissions target of 78%, as set out in the 2019 Act, in addition to taking account of the future of ambition set by the introduction of a net-zero target by 2045.

4.5 Sector-level emissions envelopes run to 2032. In order to achieve our economy-wide net-zero target, by 2045 all of our homes and buildings will need to significantly reduced their energy use and use a clean heating system.

Heat supply and emissions across residential housing

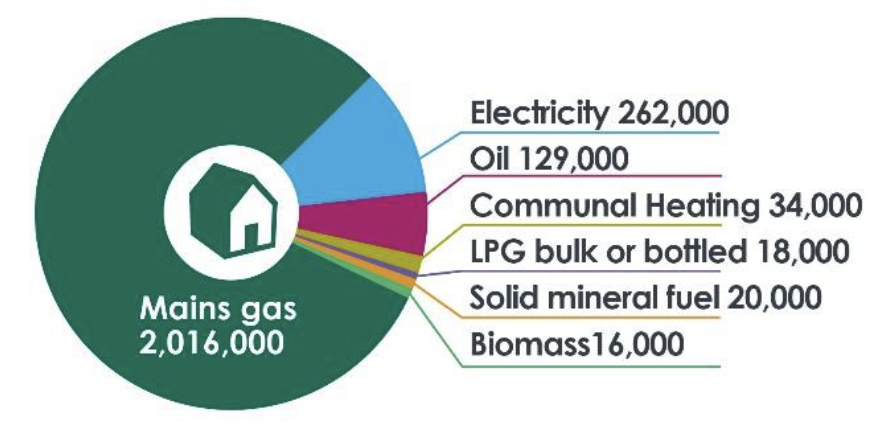

4.6 Figure 2 shows that the vast majority of Scottish homes rely on fossil fuel boilers: 81% of Scottish homes use mains gas; 5% use heating oil; and a further 2% use LPG or solid mineral fuels.[6] These fuels are referred to in the consultation, and from here on in this document, as "polluting heating systems". Together these high carbon fuels account for an estimated 88% of the Scottish residential fuel mix, none of which are compatible with our net zero target.

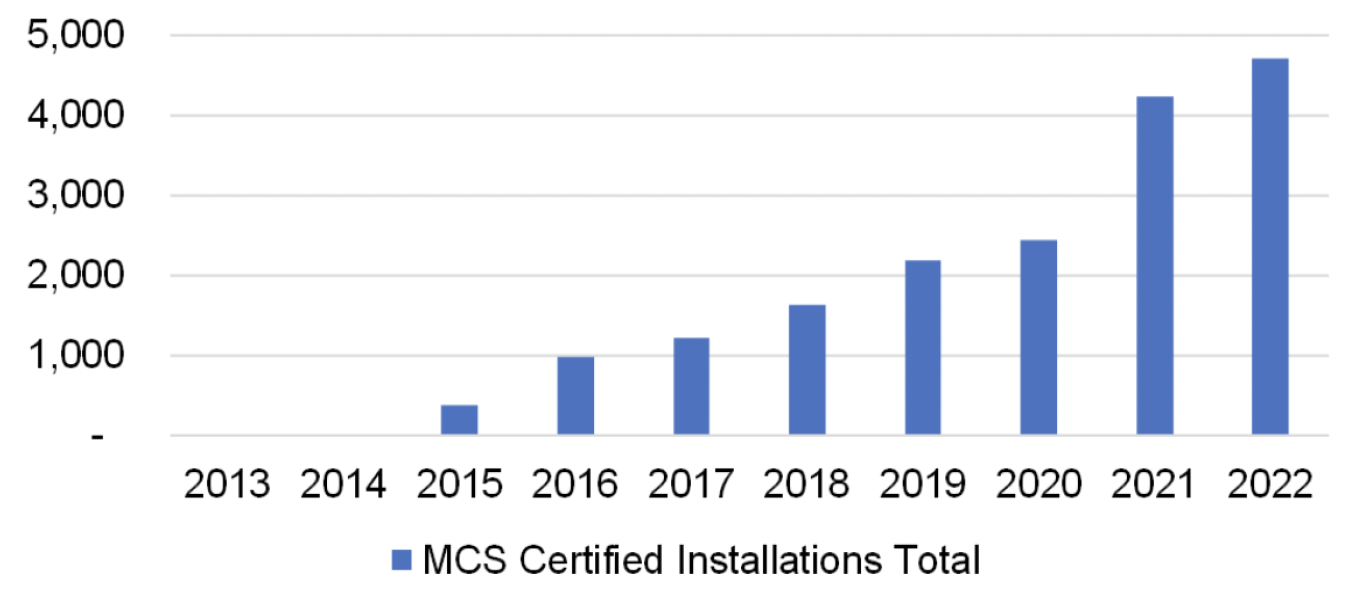

4.7 Only around 11% of households currently have a renewable or very low emissions heating system, such as a heat pump, biomass boiler or electric storage heating[7].

Source: The MCS Data Dashboard - MCS (mcscertified.com)

4.8 The Energy Saving Trust estimates that over half of non-domestic properties already use low or zero emissions sources, mainly electricity. However, the non-domestic stock varies significantly in size, and some of the largest non-domestic buildings are more likely to have mains gas systems[8].

4.9 Emissions from buildings have decreased from 10.10 MtCO2e in 2013 to 9.03 MtCO2e in 2021, a reduction of around 11%. However emissions across the economy have fallen significantly, particularly in energy supply. As a result, the share of total emissions from buildings has increased from 18% in 2013 to 22% in 2021.

Fuel Poverty Targets

4.10 The 2019 Fuel Poverty (Targets, Definition and Strategy) (Scotland) Act (2019) sets statutory targets for reducing fuel poverty, and introduces a new definition which aligns fuel poverty more closely with relative income poverty. It requires Scottish Ministers to produce a comprehensive strategy to show how they intend to meet the new targets. The 2040 fuel poverty targets require that no more than 5% of households are fuel poor, and that no more than 1% are in extreme fuel poverty by 2040.

4.11 Work to eradicate fuel poverty is linked to the Scottish Government's work to improve housing standards, and this has been considered as part of the 2019 Act[10] A Fuel Poverty Strategy was published in 2021[11] which set out policies and proposals for national and local government and third sector partners to help make strong progress towards the established targets.

Source: Scottish House Condition Survey 2019[12]

4.12 Following the UK Government budget in March 2023, the Scottish Government has estimated that from April to June 2023 there were around 920,000 fuel poor households in Scotland – 37% of all households. This is an increase of 60,000 households from estimates for the winter. The Energy Price Guarantee had set the price cap at £2,500 this winter with the universal £400 Energy Bills Support Scheme (EBSS) providing additional support to households. The £400 EBSS was being withdrawn from April 2023 and is the main driver behind this increase in fuel poverty.

Energy Efficiency and Clean Heating – policy context

4.13 Proposals to regulate energy efficiency and clean heating have been in development for many years. Scottish Ministers designated energy efficiency as a national infrastructure priority in 2015[13] and made a long-term commitment to reduce the energy demand and decarbonise the heat supply of our residential, services and industrial sectors. 2021's Heat in Buildings Strategy reiterated the role of regulations in delivering these outcomes.

4.14 The Draft Energy Strategy and Just Transition Plan (ESJTP)[14] published for consultation in January 2023, provided an update to the Scottish Energy Strategy position statement which was published in 2021[15] The draft ESJTP set out key ambitions for Scotland's energy future, including the need to transform the way we heat our homes, workplaces, communities and other public buildings.

4.15 The Bute House Agreement[16] also underlined the need to decarbonise how we heat our homes and buildings to meet the net zero pathway. It included a commitment to "phasing out the need to install new or replacement fossil fuel boilers, in off gas [areas] from 2025 and in on gas areas from 2030, subject to technological developments and decisions by the UK Government in reserved areas".

4.16 This consultation, the publication of which this year was included as a commitment in the Programme for Government 2023, brings together and seeks views on proposals which could inform the legislative framework which we believe is required to deliver on these commitments.

Energy efficiency and Zero Direct Emissions Heating – scale of task

The following provides useful context for both the domestic and non-domestic stock in Scotland.

Source: Scottish House Condition Survey: 2019 Table 17.

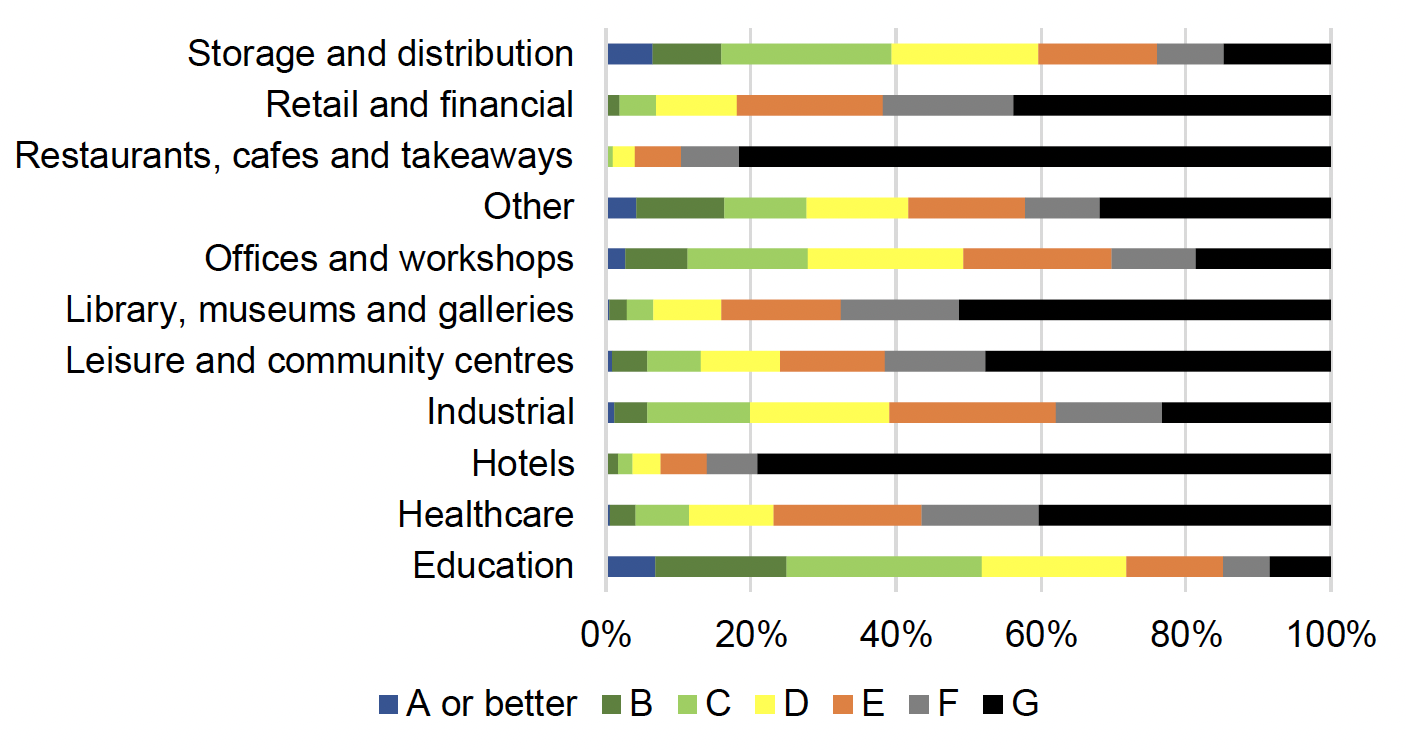

4.17 Scotland's non-domestic buildings are highly diverse and analysis shows that nearly 70% of all non-domestic premises have an EPC rating of E or worse.[17] Only 7% are rated B or better; however, this is a slight increase since 2017, when only 5% of non-domestic buildings were rated B or better[18].

Source: Scottish EPC Register non-domestic extracts 2022[19]

Contact

Email: HiBConsultation@gov.scot

There is a problem

Thanks for your feedback