Climate change duties - draft statutory guidance for public bodies: consultation

Public bodies have duties to reduce greenhouse gas emissions, contribute to the delivery of the Scottish National Adaptation Plan, and to act in the most sustainable way. This consultation seeks your views on draft guidance for public bodies in putting these climate change duties into practice.

6. Implementing the second duty: adaptation

Under section 44 of the 2009 Act, relevant public bodies have a duty, in exercising their functions, to act in the way best calculated to help deliver the Scottish National Adaptation Plan (SNAP).

All public bodies must identify the national adaptation objectives from SNAP relevant to their functions and act in a way that supports the delivery of these objectives.

Organisations will have varying degrees of influence in relation to adaptation in Scotland depending on their particular role, functions and responsibilities, but all public bodies need to be resilient to the future climate and to plan for business continuity in relation to delivery of their functions and the services they deliver to the wider community.

To help demonstrate compliance with this duty, public bodies should:

- undertake a climate related risk assessment or assessments

- develop and implement an adaptation plan or plans with, as best practice, regard to just transition principles

- ensure that appropriate climate risks are included on corporate risk registers

- where applicable, note the specific adaptation actions assigned to them in the SNAP and align their work with these

- actively seek to work in partnership with other organisations to develop and implement wider placed based adaptation plans

- undertake the above giving due consideration to their physical assets including buildings, land and fleet; their staff and service users; the services they deliver; and the functions they exercise.

Key outcomes will be that public bodies:

- have a sound understanding of why adaptation is important for their organisation and what the impacts of climate change could mean, and will have identified and assessed their risks, vulnerabilities and any potential opportunities

- have identified and assessed the adaptation options, and have measures in place to implement their chosen strategies so that their physical assets, daily operations and service delivery are adapted to the changing climate and are resilient to its impacts

- monitor and evaluate implemented measures to ensure that adaptation efforts remain sufficient and responsive to changing conditions

- where applicable, contribute to the achievement of the specific adaptation outcomes assigned to them in the SNAP, and are able to track and report on delivery

- contribute to the effective adaptation of the places in which their sites, operations and services are located and delivered.

6.1 Introduction to the second duty

This chapter starts by providing a brief explanation of what climate adaptation is, why it is important and by providing context for adaptation action. It is understood that public bodies will be at differing levels of maturity in relation to adaptation action. The guidance aims to provide a baseline level of information, aligned with the guidance and resources developed by the Adaptation Scotland programme.

The chapter then moves on to provide more technical and complex guidance aimed at organisations with greater adaptation needs, either owing to the size and nature of their estate and assets, or due to their function, i.e. those bodies responsible for delivering essential services.

6.2 What is adaptation to climate change?

The climate is changing. Current advice from the UK Climate Change Committee is that Scotland needs to adapt to 2ºC of warming and assess the risks up to 4ºC [29]. Whilst global efforts to mitigate further warming will continue, we must ensure we are prepared for the future climate.

Adaptation refers to adjusting to the impacts of climate change, including hazards such as flood and heatwaves. Adaptation involves the deliberate and systematic adjustment of systems and processes to effectively address both anticipated and actual climate change impacts. This comprehensive approach focuses on increasing preparedness to future extreme weather events, reducing existing vulnerabilities, increasing climate resilience, mitigating damages caused by climate change impacts, and takes advantage of positive opportunities that changes may offer.

Adaptation to climate change addresses a range of challenges enabling societies and ecosystems to thrive in a changing climate. It is an ongoing process that requires collaboration and flexibility within and between organisations; and integration into broader strategies, plans and operational practices, including links to policy areas such as climate change mitigation, land management, health and welfare.

Human and natural systems are complex. Adaptation will take place within the context of significant societal challenges including those related to population health, the cost of living crisis, and the biodiversity and loss of nature crisis. Integrated and aligned policy actions can deliver multiple outcomes for population health, equity, the environment and the economy, contributing the Scotland's National Outcomes and the UN SDGs.

Key areas of focus for adaptation in practice include understanding when and how to adapt infrastructure to cope with increased weather extremes, and changing land management practices. There are however areas of significant overlap with activities that could help to meet both mitigation and adaptation goals, such as naturalising river catchments for flood risk and water management, woodland restoration, blue-green infrastructure and education, all of which will deliver multiple benefits. Figure 14 demonstrates the differences and the areas of overlap between adaptation and mitigation.

Figure 14: Venn diagram showing the differences and the crossovers between mitigation and adaptation (based on a diagram developed by Highland Adapts)

Mitigation – actions that reduce the emissions that contribute to climate change. Measures include sustainable transportation, energy efficiency, renewable energy, waste reduction and active travel.

Adaptation – actions that manage and reduce the negative impacts of climate change. Measures include emergency management, knowledge sharing, infrastructure upgrades, flood protection, heat management, business continuity, wildfire resilience and coastal management.

Actions and measures that contribute to both mitigation and adaptation include healthy ecosystems, new energy systems, water conservation, sustainable livestock management, local food, connected communities, education, sustainable tourism, responsible fisheries and the circular economy.

6.3 How to adapt

6.3.1 Key principles for effective adaptation

The Climate Change Committee has set out ten principles for effective adaptation as part of the third Independent Assessment of UK Climate Risk (CCRA3) [30]. These can be used to sense check adaptation planning or decision making and to ensure any initial planning takes big picture adaptation aims into account.

Figure 15: Ten Principles for effective adaptation (based on a Climate Change Committee visualisation from CCRA3 [31])

The ten principles include:

1. Ensuring that adaptation plans fit the vision for a well-adapted UK and Scotland. Public bodies can do this by reviewing the SNAP3; identifying the national adaptation outcomes relevant to them; and contributing towards those outcomes.

2. Integrating adaptation into other policy areas and organisational priorities. A host of organisational priorities and goals will be undermined by the effects of climate change. Current policies on climate change mitigation and healthcare for example should be explored to determine where and how adaptation could be addressed simultaneously, while addressing any co-benefits or trade-offs.

3. Organisations should be planning for tomorrow's climate and not today's. Public bodies can do this by considering the lifetime of plans, policies, projects and assets and making decisions based on future warming scenarios and the public bodies own climate risk assessment.

4. Adaptation plans should aim to avoid 'lock-in'. An example of lock-in is building new homes without designing in adaptations to future conditions including extreme heat. Retrofitting windows and shutters is around four times more expensive than including them at design stage. Adaptation plans should create flexibility within an organisation or body, offering different pathways for the future and the ability to deal with extreme events and hazards.

5. Adaptation plans should allow preparation for unpredictable extremes by increasing flexibility. Undertaking storyline approaches or 'what if' scenarios could be used here, and more headroom could be given to policies and operations to account for any sudden extreme changes including reaching climate tipping points.

6. Interacting risks or 'compound risks' such as a heatwave and drought occurring simultaneously can cause significant challenges when addressing climate risks. Adaptation planning should consider a range of hazards and how they may interact. Siloed thinking can pose problems particularly for risks that interact or those that could lead to cascading impacts that are dealt with by different groups or departments. This highlights the importance of collaboration between groups and with a range of stakeholders. Examples of regional adaptation collaborations include Highland Adapts and Climate Ready Clyde.

7. Understanding threshold effects is a key part of an effective adaptation plan. Bodies should understand what thresholds exist for their critical assets and services. Risk assessments that look at average changes over time assume that a risk will gradually increase, so can miss specific points that 'tip' the system or asset into a different state.

8. Adaptation plans should reduce inequalities and focus on socially just outcomes. Actions to address climate change could also exacerbate existing inequalities without careful planning, known as maladaptation. This includes using the holistic definition of risk as a function of hazard, exposure and vulnerability. This highlights the importance of understanding where vulnerabilities lie. Collaborating with community groups and a wide range of relevant stakeholders can help to address this. Use of participatory tools, such as the Place Standard with a climate lens and health impact assessments, can be used to identify and assess differential impacts of adaptation and policy responses, take steps to maximise health, wellbeing and equity benefits and minimise harms.

9. Opportunities should also be considered when creating adaptation plans. This could relate to, for example, opportunities that come from milder winters as well as opportunities for heightened collaboration and co-benefits with other policy areas. This includes integrating mitigation and adaptation policy.

10. Funding and resourcing are critical to effective adaptation. Knowledge sharing could help in this regard. In addition, having strong governance and accountability in place within a body or organisation is key to be able to monitor and track progress against relevant indicators.

6.3.2 Getting started

The Adaptation Scotland programme provides advice and support to help organisations, businesses and communities prepare for, and build resilience to, climate change.

The Adaptation Capability Framework for the Scottish public sector, developed by Adaptation Scotland, outlines four capabilities needed for an organisation's adaptation journey. It describes 42 tasks to develop these capabilities over four stages from 'starting' to 'mature' (table 3). The four capabilities are:

- understanding the challenge

- organisational culture and resources

- strategy, implementation and monitoring

- working together.

The Capability Framework is supported by a handbook which contains information related to each of the tasks.

Stage |

Understanding the challenge |

Organisational culture and resources |

Strategy, implementation and monitoring |

Working together |

|---|---|---|---|---|

Starting |

UC1A Learn about Scotland's changing climate and impacts UC1B Develop understanding of climate risk and vulnerability UC1C Record and consider the impact of recent weather events on your organisation |

OC1A Consider how adaptation fits with your organisation's objectives OC1B Identify resources already available for adaptation OC1C Identify key internal stakeholders for adaptation |

SIM1A Consider how you contribute to Scotland's adaptation outcomes SIM1B Identify existing adaptation work within your organisation SIM1C Define strategic adaptation outcomes and or vision |

WT1A Define your objectives and opportunities for joined working WT1B Identify relevant groups, partnerships and forum WT1B Identify relevant groups, partnerships and forums |

Intermediate |

UC2A Map out how your organisation's functions might be affected by climate change UC2B Consider scenarios for future climate change impacts UC2C Engage with stakeholders using participatory approaches |

OC2A Engage with colleagues to optimise adaptation opportunities OC2B Define resource requirements to plan and deliver adaptation OC2C Establish governance |

SIM2A Identify a range of potential adaptation actions SIM2B Identify plans, policies and procedures that can include climate adaptation SIM2C Deliver initial adaptation actions |

WT2A Engage with relevant groups, partners and forums WT2B Co-ordinate with partners to deliver initial actions |

Advanced |

UC3A Carry out climate change risk assessment UC3B Integrate climate adaptation knowledge into internal training and procedures UC3C Improve understanding of stakeholder needs |

OC3A Ensure key people are responsible for adaptation actions OC3B Develop an investment plan to mobilise resources for adaptation |

SIM3A Appraise adaptation options SIM3B Develop an adaptation strategy and action plan SIM3C Develop a monitoring approach for achieving your adaptation outcomes |

WT3A Formalise partnership working WT3B Develop communication activities with partners |

Mature |

UC4A Undertake project-level risk assessment UC4B Mainstream climate change risk assessment UC4C Identify knowledge gaps, seek expertise and foster links with research and innovation |

OC4A Review and update governance arrangements for adaptation OC4B Secure resources to plan and deliver adaptation |

SIM4A Implement a programme of adaptation actions SIM4B Adopt an adaptive management cycle for adaptation planning |

WT4A Enhance long-term partnership working WT4B Lead in networks and peer organisations |

The Adaptation Scotland starter pack provides information for bodies who are beginning their adaptation journey. The starter pack outlines how to begin identifying what impacts climate change could have on different functions within bodies before finding links between organisational priorities and adaptation. The starter pack also provides guidance on how to identify resources and relevant stakeholders.

The following checklist is based on the 'starting' level of the Adaptation Capability Framework. All public bodies should complete the actions outlined in this checklist.

Further information relating to each item is provided the sections below. Please refer to the Adaptation Scotland website for a comprehensive overview and for further guidance.

Adaptation starter checklist

Understanding the challenge - public bodies should:

- learn about Scotland’s changing climate and impacts

- develop understanding of climate risk and vulnerability

- record and consider the impact of recent weather events on your organisation

Strategy, implementation and monitoring – public bodies should:

- consider how you contribute to Scotland’s adaptation outcomes

- identify existing adaptation work within your organisation

- define strategic adaptation outcomes and or vision

Organisational culture and resources – public bodies should:

- consider how adaptation fits with their organisation and its objectives

- identify resources available for adaptation

- identify key internal stakeholders for adaptation

Working together – public bodies should:

- define your objectives and opportunities for joint working

- join and participate in relevant professional and adaptation networks

- identify relevant groups, partnerships and forums

6.3.3 Understanding the challenge

Under the 'understanding the challenge' capability, bodies should start by:

- learning about Scotland's changing climate and impacts.

- developing an understanding of climate risk and vulnerability.

- recording and considering the impact of recent weather events on your organisation.

Raising awareness of adaptation and understanding of why it is important within bodies is the first step to becoming an adaptative organisation.

The UK Climate Change Risk Assessments (CCRA) reports identify 61 risks and opportunities from climate change across the UK. Some key risks for Scotland include the:

- impact of a changing climate and extreme weather on terrestrial species and habitats

- cascading failures for infrastructure networks

- the risk of climate change impacts, especially more frequent flooding and coastal erosion, causing damage to our infrastructure services, including energy, transport, water and Information and Communication Technologies (ICT).

- impact of high temperatures on health and wellbeing

- impact of flooding on people, communities and buildings

- impact of flooding on business sites

- coastal businesses impacted by extreme weather, sea level rise, coastal erosion and flooding

- decreasing yields of food internationally affecting supply

- impact of vector borne diseases on health

- international interaction and cascades of named risks.

As a next step, public bodies should, as a minimum:

Explore future projected changes in Scotland’s climate, for example using the Met Office climate data portal.

Read the latest Climate Change Risk Assessment (CCRA) national summary report for Scotland to explore the full list of risks and opportunities identified for the UK and Scotland.

Identify weather events that have impacted their organisation in the past – the response and an understanding of the impacts of these events could help to inform the creation of an adaptation strategy. Consider how such weather events could be different in the future, e.g. more severe or more frequent.

Create a briefing on what climate change is and why adaptation is important for their body including what the impacts of climate change (and the risks set out in the CCRA report) could mean for their organisation.

Consider investing in training on climate change adaptation and resilience (or ensuring that any carbon or climate training currently available includes climate adaptation) to ensure that technical terms and fundamental concepts of adaptation are understood.

Read the UK Health Security Agency (UKHSA) reports on the Health Effects of Climate Change in the UK to gain a deeper understanding of the risk to population health posed by climate change, where appropriate.

6.3.4 Strategy, Implementation and Monitoring

Under the 'strategy, implementation and monitoring' capability, bodies should start by:

- considering how they contribute to Scotland's adaptation outcomes

- identifying existing adaptation work within the body

- defining strategic adaptation outcomes and or a vision.

Planning and implementation are crucial elements to achieving the long term challenge of becoming a more adaptive organisation. Adaptation should be embedded within an organisation's function and purpose. An important first step is to identify actions already being taken within an organisation. It is very likely that bodies are already undertaking adaptation actions, related to flooding responses for example, even if they are not recognised as such.

The public sector has a pivotal role to play in building Scotland's overall climate resilience by helping to deliver the Scottish National Adaptation Plan (SNAP). Looking at the bigger picture can help to make the most of opportunities and to define a public body's strategic adaptation vision and outcomes. Bodies should consider how their adaptation actions can contribute to the SNAP outcomes and objectives.

As a next step, public bodies should, as a minimum:

Identify actions that are already delivering adaptation – for each service or department relevant to the body, provide examples of how it may be affected by climate change and any existing action, plans or policies that support adaptation actions in that service or department, and how they could be strengthened.

Read the Scottish National Adaptation Plan and its outcomes and objectives.

Consider how each SNAP objective may be relevant to their body.

For example, for SNAP3 outcomes:

(C5) Culture and historic environment: Scotland's historic environment is preparing for a future climate, and the transformational power of culture, heritage and creativity supports Scotland's adaptation journey.

Public bodies may have direct responsibilities for looking after the historic environment, either through buildings or monuments on their own estate or as part of their wider function; have relevant regulatory powers such as those related to Planning; or provide funding or other support to the cultural and creative sectors.

(PS4) Transport system: the transport system is prepared for current and future impacts of climate change and is safe for all users, reliable for everyday journeys and resilient to weather-related disruption.

Public bodies including local authorities, Transport Scotland and the Regional Transport Partnerships will have direct responsibilities in relation to this outcome. However other bodies may own or manage land, other assets or deliver services that could impact on transport systems. For example, a body may own land at risk of landslides that, should a landslide occur after a heavy rainfall event, would block a road. Or, a body may own land higher up a river catchment area where a change in land use could help prevent flooding and related road and rail closures downstream.

(B1) Increasing business understanding of climate risks and adaptation action: businesses understand the risks posed by climate change and are supported to embed climate risks into governance, investment, and operations, and are collaborating on effective adaptation action.

While the enterprise agencies could be seen as the bodies with the most direct responsibility, all public bodies will work with businesses in some way and can use their influence to contribute to this outcome. For example, bodies including local authorities may provide grants or other funding to businesses in their area and could include aspects related to climate risk and governance in the funding conditions. All public bodies will procure goods and services, and could use procurement exercises to further progress towards this outcome. Bodies can also work to influence members of adaptation partnerships they are part of, and to encourage businesses they work with, where appropriate, to join such partnerships.

Bodies should consider their contribution to the outcomes in a broad way.

6.3.5 Organisational culture and resources

Under the 'organisational culture and resources' capability, bodies should start by:

- considering how adaptation fits with their organisation and its objectives

- identifying resources available for adaptation

- identifying key internal stakeholders for adaptation.

Adaptation strategies and actions can be implemented in a way that benefits from and influences organisational culture. Adaptation action can be progressed by reviewing and identifying existing structures, legislative drivers and resources available. Understanding how adaptation can support the delivery of strategic objectives, and wider co-benefits for population health, wellbeing, equity and biodiversity, can help to communicate its relevance and importance. Another important step is to identify where adaptation is best placed within a body including what groups, departments or committees will develop and deliver adaptation plans internally.

As a next step, public bodies should, as a minimum:

Consider what motivated their organisation to address climate adaptation. Some common triggers for taking action on adaptation are:

- developing and reviewing your local climate risk assessment

- providing support for service area reports and business case development

- impacts of an extreme weather event (e.g. a flood or heatwave) on operations, services, finances, health or safety

- increasing resilience to disruption to services from extreme weather

- ethics and public expectations

- statutory duties

- investing money to save in the future

- avoiding future liability

- making decisions about the resilience of long-term assets (e.g. infrastructure or land use or land management practices).

Consider what their organisation wants to achieve with their adaptation plan or strategy. For example:

- a more climate resilient local area

- robust reporting for service areas

- an updated risk register

- greater protection of properties against flooding or reduced vulnerability of care homes to extreme heat events

- cost savings for responding to severe weather events

- realise population health, wellbeing and equity benefits and contribute to multiple social outcomes including National Outcomes and the UN SDGs.

Consider how climate change may impact their organisation’s strategic priorities.

Consider what the risk appetite of their organisation is. For example, does their organisational policy specify what acceptable and unacceptable risk is? How does this change for different assets or services (including critical assets and services)?

Work with their risk manager or appropriate team or department to understand any existing approaches to managing weather and climate related risks.

Consider if there are groups, committees or partnerships within their organisation who could be involved in adaptation work.

6.3.6 Working together

Under the 'working together' capability bodies should start by:

- defining their objectives and opportunities for joint working

- joining and participating in relevant professional and adaptation networks

- identifying relevant groups, partnerships and forums

Collaboration is a critical element of adaptation planning and implementation. No organisation can adapt alone. By joining networks bodies can share knowledge and learning from other groups. Delivering adaptation actions often requires partners working in a collaborative relationship. This includes within and outwith their own organisation, working with community groups or community planning partnerships for example. There are already networks and groups that bodies could consider joining.

As a next step, public bodies should, as a minimum:

Identify existing groups, partnerships or forums that they could join or collaborate with. Consider their aims, existing adaptation links or on-going work and potential future adaptation links with their own organisation.

Some groups to consider include:

- Community Planning Partnerships

- Community climate hubs and community action networks

- Local plan district groups

- Regional climate adaptation and resilience initiatives, such as those listed on the Adaptation Scotland website.

Join relevant professional adaptation networks. Some examples include:

- Sustainable Scotland Network

- Public Sector Climate Adaptation Network

6.3.7 Overcoming adaptation challenges

Acknowledging any potential barriers or constraints from the outset is an important step in developing an adaptation plan. These can also then be incorporated into monitoring and review processes. How these barriers can be minimised should also be considered as well as how to maximise the relevant drivers to adaptation.

Some common drivers of adaptation include:

- increased awareness in an organisation after an extreme weather event such as a flood or heatwave event

- leadership

- societal pressure from local or national groups or campaigns

- need to comply with statutory guidance or legislation

- need to ensure delivery of services.

Some common barriers or constraints include:

- lack of buy-in or scepticism from senior leaders and or colleagues

- lack of awareness in organisations

- lack of skills and knowledge of adaptation

- coordinating resourcing (time pressures and competing priorities)

- a focus on short-termism

- a focus on mitigation – the importance of adaptation not being recognised

- siloed policy making – climate adaptation is a complex problem and there are challenges to taking a whole systems approach.

As a next step, public bodies should, as a minimum:

Consider what their organisation’s drivers and potential barriers or constraints are.

Consider how their adaptation planning can minimise barriers and or maximise drivers. For example, training on climate change adaptation and mapping their organisation’s priorities to climate change impacts could help colleagues and senior leaders to understand the need for adaptation action.

Share the Leaders’ Climate Emergency checklist with senior leaders which outlines the requirement for action on climate adaptation.

6.4 Going further: beyond the basics

This section aims to provide more technical guidance on adaptation planning and compliance with the core duty to contribute to the Scottish National Adaptation Plan and reporting on progress.

It covers a whole systems approach to understanding climate risk.

It is intended to support organisations that may have a greater role in adaptation or greater needs owing to:

- infrastructure

- land and natural resource management

- complex operations subject to multiple interdependencies

- multiple sites across Scotland

- critical functions such as health, social care, education, emergency services provision or defence.

It is important to note that public bodies may be starting their adaptation journey in some capabilities, but might be more mature in others. Therefore, this guidance is likely be useful wherever public bodies are on their journey.

Public bodies should take responsibility to ensure understanding of the challenges of climate change, their role in providing solutions, and in leading the way with action to support an adapting and resilient Scotland. Public bodies should be engaging, collaborating and leading beyond their boundaries to reduce risks, protect the natural and built environments, communities and organisational staff.

All public bodies have a vital role in influencing, supporting, and taking adaptation action, internally and across whole systems, beyond their organisational boundaries, regardless of land ownership, scope or size.

6.4.1 A whole systems approach to understanding climate risk

The effects of climate change influence many complex relationships within organisations, places and ecosystems. Climate hazards affect population health, health, wellbeing and equity as a consequence of the impact on natural and human systems including physical infrastructure, emergency management, supply chains, economic vitality, and many social issues.

When trying to understand climate change risk and vulnerability, particularly when the scale of assessment is beyond project level, it can often be simpler to break the hazards and risks into smaller segments. It helps to take the colossal, complex problem of a changing climate, and simplify it into more manageable parts, providing an easier route to tangible actions for adaptation.

However, viewing climate risk in segments negates the bigger picture: public sector bodies cannot understand the full risk profile if they do not bring the segmented parts back together, view them as a whole, and consider how they behave in a wider context. Climate hazards are and will occur and interact simultaneously, increasing a likelihood of cascading risks – a chain reaction of events set off by an initial hazard. Understanding and preparing for diverse cascading events is crucial as these interconnected sequences can escalate the complexity and severity of subsequent risks, posing challenges to effective response and ongoing adaptation efforts.

Consequently, public bodies' vulnerability and responses will be shaped not only by changing socio-economic and demographic factors but also by increased probability of cascading risks. To decrease the risk and reduce the adverse effects of cascading hazards, public bodies should ensure they explore both a range of possible future climate scenarios and socio-economic context.

Cascading risks in the context of disaster and adaptation involve a chain reaction of events set off by an initial hazard. Examples include physical cascades, where one event leads to another (e.g. heavy rainfall leading to river overflow which in turn could trigger landslides, dam failures and local flooding) and social cascades where societal responses amplify risks (e.g. panic worsening evacuation efforts, overwhelming emergency services and hindering an effective response). These interconnected events highlight the need for comprehensive adaptation strategies that address both the primary hazard and its potential cascading impacts. In the context of adaptation understanding and preparing for these diverse cascading events, both natural and societal, is crucial for effective disaster management and recovery.

What is needed is a systems approach - an approach that requires organisations to think holistically, and beyond of their own organisation and sector, to the wider place and context they are situated in; how the actions they do or do not take may impact the whole system.

A systems approach helps to consider interactions between different parts of the system, related uncertainties, and how these can combine to affect an outcome. A clearer understanding of the entirety of the system will enable the identification of the multiple intervention points required to minimise risk, build resilience, and adapt to the future climate.

Of course, there will be actions and activities that public bodies can control and deliver independently, and they should act on these, but there will be areas of adaptation that require collaboration due to interlinking dependencies. Intervention in one part of the system will impact on other areas of the system, and could impact on multiple outcomes with potential unintended consequences because of the complexity and interdependencies.

Example: A local authority may be concerned over public water supply availability for their community during periods of drought. They may reach out to Scottish Water to get a better understanding of risk in their area, who in turn may offer to work in partnership to ensure decisions the local authority makes are not causing further future ‘lock-in’, increasing vulnerabilities to this risk. They may also engage with local landowners who have a part to play to ensure our natural landscape supports public water supply. The local authority may also look to engage and work in partnership with a wide range of community groups, and education establishments to ensure education about water usage is on the agenda in an accessible format for all. Public bodies should seek to understand the whole system in which they operate and should proactively nurture opportunities to collaborate to deliver adaptation and wider multiple benefits in partnership, in addition to reducing risk.

Through working in partnership, public bodies will ensure they take a just and inclusive approach to adaptation. By ensuring adaptation plans are built on inclusivity, equity, resilience, and shared responsibility, this minimises disparities and the likelihood of maladaptation and unintended consequences. It also ensures that responses deliver multiple benefits through adaptation for nature, biodiversity, business, equality, and public health.

Whole systems thinking also supports place based approaches to climate change, inclusive of and beyond the scope of adaptation. Public bodies should, where appropriate, link in with relevant policy frameworks, for example the National Planning Framework, Local Development Plans and national sectors (e.g. water, energy, transport, health).

6.4.2 Climate change risk assessments: best practice

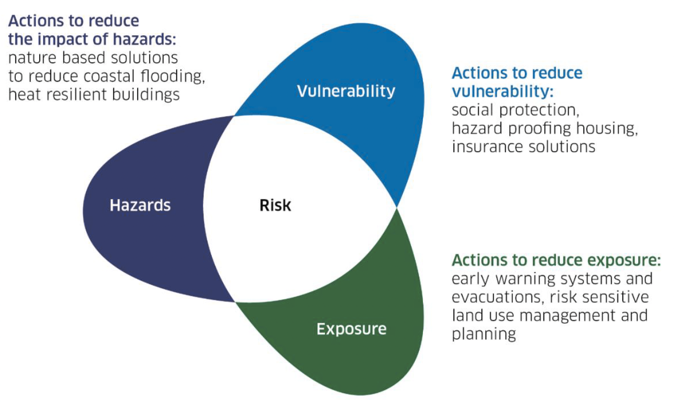

Risk is considered as the interaction between a hazard or weather event, exposure and vulnerability. It can be defined as the potential for adverse effects on human health, ecosystems, economies and societies resulting from the interactions between climate related hazards (such as extreme weather events, sea level rise and temperature changes) and the vulnerability and exposure of a specific region or system.

Hazard refers to a specific climate related event or phenomenon with the potential to cause harm or adverse impacts on the environment, human health, economies or societies. Hazards associated with climate change include extreme weather events (hurricanes, floods, droughts and heatwaves) sea level rise, changes in precipitation patterns and shifts in temperature.

Exposure refers to the degree to which a system (such as a human population or ecosystem) or asset is subjected to climate related hazards. Exposure is highly context specific and is influenced by various factors including geographic location, land use or land management practices, infrastructure and socio-economic conditions. It encompasses not only the physical hazard posed by the changing climate but also considers factors such as safety or mitigating measures that may be in place, societal vulnerabilities and governance.

Vulnerability is the extent to which a society, economy or ecosystem is at risk of adverse impacts from climate related hazards. This concept focuses not only on physical exposure to climate driven events but considers socio-economic factors like poverty, inequality and access to resources. It also considers the system's capacity to recover and adapt following climate related events.

Figure 16: Simplified risk framework showing risk as a function of hazards, exposure and vulnerability (adapted from IPCC [33])

6.4.3 Why assessing vulnerability is important

Due to existing societal inequalities, certain communities or groups experience climate change impacts disproportionately. Vulnerability can be the result of marginality and lack of access to resources that can be exacerbated by a hazard.

The concept of intersectionality – multiple and compounding inequalities – is highly relevant to the assessment of vulnerability to climate change. Climate change and social, economic and personal factors (such as gender, race, income, age and health status) can act together as risk multipliers, increasing the impacts on health, and health and other inequalities [34]. Taking an intersectional approach can identify and highlight the lived experiences of people with intersecting identities, and help to develop policies, plans and services that address structural inequalities [35].

For example, green spaces can provide shade during heatwaves and can help with rainfall run-off, and these tend to be found in higher-income areas. A study on Wales and England showed that new homes built in economically deprived areas between 2008 and 2018 are more likely to become exposed to high flooding risk as opposed to new housing situated in higher income areas [36]. This vulnerability often arises from challenges such as limited ability to secure property insurance and difficulties in evacuating during floods. In addition, elderly people and those with underlying health conditions can be disproportionately impacted by heatwaves, for example. The heat throughout summer 2022 has been estimated to have led to the death of approximately 60,000 people in Europe and around 3500 in the UK [37].

Any adaptation plan or policy should address inequalities in the first place and embed fairness by acknowledging that different groups and communities will be impacted by hazards and weather extremes differently. The Scottish Government's Equalities and Fairer Scotland Duty impact assessment may contain research to aid considerations. Further guidance on equalities is provided in chapter 3.

6.4.4 Climate change scenario analysis

Further changes in the climate by 2050 are inevitable as the world will take several decades, at the very least, to reach net zero emissions. But longer-term (post-2050), changes in the UK's climate will largely depend on how rapidly global emissions are reduced [38]. Climate scenario analysis can help address this future uncertainty.

Current policies in place around the world put the world on track for a central estimate of 1.8 to 3.5°C above preindustrial levels by 2100, with uncertainty due to the climate response to greenhouse gas emissions meaning that global average surface temperatures of in excess of 3.5°C by 2100 are still a possibility. Warming reaching 4ºC above preindustrial levels by 2100 remains at the upper end of possible outcomes [39].

In Scotland, temperature rises of up to 2°C would bring warmer temperatures in all seasons, drier summers and wetter winters, more extreme weather events and sea level rise. However, a more sluggish jet stream could periodically lead to prolonged cold winters as well as hot summers. These trends will be felt to a greater or lesser extent across different localities, and the change will not be steady, linear or gradual. These changes will have different impacts for different sectors and places, which means public bodies should understand, plan for and adapt to these changes urgently. By understanding the risks associated with climate change public bodies can integrate these into internal systems and procedures and make informed decisions based on actual or expected changes.

In addition to considering all of the parts of the system that could be impacted by climate change, it is also important to assess risk in varied possible future climate scenarios. Scottish Government has committed to developing a climate scenario decision tool to support the public sector. As an initial step, research has been commissioned via ClimateXChange (CXC) on 'Future climate in today's decision-making'. This research is due to be published by spring 2025.

While Scottish Government considers the CXC research and development of a decision tool, this guidance recommends that public bodies should seek to understand what a 2°C and 4°C scenario will mean for organisational climate risk at multiple points in the future (e.g. 2050s and 2080s), apply these findings to adaptation plans, and where possible make publicly available what climate futures they are planning for. Where applicable, they should also utilise projections for socio-demographics of the population, as this will influence who is impacted by the changing climate, and how.

Example: A land manager is planning the next iteration of a local land management plan, and they are looking to see how climate change will impact the landscape in addition to infrastructure in the area. They have a bridge in the area that is due for maintenance in 2027, and land that is due for commercial timber replanting now that will stand for the next 60 years and is a very important asset.

They choose to look at 2°C and 4°C climate scenarios for the years 2050, 2080 and 2100 to assess the climate risks and vulnerabilities. They decide to replant this area of forest in a way that is resilient under a 3 to 4°C warming scenario as the trees will be standing beyond 2080. This includes consideration of the changing growing conditions, water availability, the changing risks from pests and diseases and the species mix. They decide not to take immediate action on adapting the bridge as, short term, the climate scenarios suggest limited damage that can be tolerated. However, they plan to adapt the bridge at the next maintenance cycle to futureproof it and save on resources.

They plan out future decision review points in line with climate risk assessment review points and ad hoc reviews as new developments come forward from climate science and review bodies, like the Met Office, Climate Change Committee and IPCC. They also agree to review should experience suggest that they may not have gone far enough in their adaptation measures, for example if they see a more rapid change in flooding frequency or severity.

Public bodies should be clear on the climate change pathways and scenarios, and the risks and implications for their services that they have considered as part of their adaptation planning.

It is important to consider possible interdependencies when conducting a climate change risk assessment, to ensure possible impacts to the organisation are fully sighted, in addition to the impacts extending beyond the body's boundaries.

Figure 17: Interdependencies between climate impacts and key services

Roads and access – extreme weather events such as flooding or storms can block access to sites, making emergency response more difficult.

Power outage – power outage caused by storms, flooding, drought or high temperatures. For example, power failure resulting from cables or transmissions overheating or damage from high winds or falling trees.

Telecoms – loss of ICT or telecoms service resulting from storms or temperature extremes.

Supply chain – loss of access to, for example, chemicals, replacement parts and contracted maintenance teams, resulting from an inability to provide services as a result of storm or flood damage or extremes in temperature limiting production capability.

Public bodies should consider what the wider impacts to Scotland are from climate-related incidents occurring on their land or within their boundaries and should seek to work in partnership with other stakeholders to progress adaptation in these areas. Disruption to core infrastructure and services have a significant impact on health, wellbeing and equity, for example people being unable to access work, education, food, social support, health and social care.

If, for example, a public body manages assets, land or infrastructure that runs along a water course that is at risk of flooding, it is expected that consideration is given to the potential upstream and downstream impacts, and the consequences arising from decisions made within the organisation's management area. However, this is not to say that it is the responsibility of that organisation to mitigate upstream and downstream risk in isolation – partnership working is required.

Public bodies should consider the knock-on consequences of emission reduction strategies on adaptation efforts, e.g. considerations to decarbonise buildings or restore peatland should also include considerations around future climate scenarios, risk and vulnerabilities.

Public bodies should consider the wider (or interdependent) risks arising from climate change, for example vulnerabilities to power supplies, communications, transport, or supply chains for critical materials and components, and how they might increase resilience where appropriate.

It is considered best practice for public bodies to make organisational climate risks publicly available, and where applicable for relevant public bodies, provide a link to where they can be found in their annual report under the mandatory reporting duty.

The Adaptation Scotland programme has developed guidance and tools to support organisations in undertaking climate change risk assessments. They have also developed guidance to help identify climate hazards in the workplace, which are essential to be sighted on in order to protect staff in a changing climate. Local Partnerships have also developed a climate adaptation toolkit and climate risk and opportunities matrix template.

Public bodies should review climate risks in line with relevant organisational and business planning cycles, SNAP cycles or where new climate risk data becomes available, where proportionate.

Additional tips for carrying out a climate change risk assessment can be found below.

6.4.5 Tips for carrying out a climate change risk assessment

Engagement and collaboration

- Even if there is a lead person or team conducting the risk assessment, be sure to involve stakeholders from across the business to test thinking, particularly for indirect risks and knock-on impacts

- Ensure early engagement with key stakeholders to ensure there is meaningful participation in the process.

- Where appropriate, involve external parties and communities in the risk assessment. This will help to get a clearer picture of how hazards play out across a system and what interdependencies exist. Think about how stakeholders are identified, whose interests they represent, and encourage diverse views and experiences.

- Within an information governance framework, share data between organisations as far as possible, particularly where there is cross-over or similarities in place, sector, etc. This greatly reduces duplication of resources, data, and effort and fosters collaboration.

Data

- Decide early on if the risk assessment will be data-informed or data-led based on the needs of the organisation. This will have an impact on certainty levels and the time required, amongst other factors.

- Don't consider hazards in isolation: there will often be instances where multiple hazards coincide and exacerbate vulnerabilities, e.g. high wind gusts may coincide with flooding.

- Consider worst case scenarios, socio-economic factors, population health profiles and tipping points to create a full picture of potential risks and what impacts the organisation may face in these scenarios. This could work well as a workshop with a variety of stakeholders to ensure interdependencies, differing viewpoints and expertise are considered.

- Ensure current risk is assessed and how recent weather events have impacted the organisation, people and systems.

- Ensure data is from credible sources, particularly narrative data. Make use of sector and subject experts and reports they may have issued to bolster numerical data and climate projections.

- Plan future re-evaluation points.

Useful data sources:

- Met Office Climate data Portal and Local Authority Climate Service

- Local Climate Adaptation Tool (LCAT)

- Met Office UKCP18 products

- National Trust's Hazard Mapping Tool

- National summaries (CCRA3-IA) - UK Climate Risk

- Datasets - British Geological Survey (bgs.ac.uk)

- Climate Risk Indicators (uk-cri.org)

- UK Climate Risk

- Sixth Assessment Report — IPCC

- ForestGALES - Forest Research

- Welcome to the Climate Change Hub - Forest Research

- Flood maps | Scottish Environment Protection Agency (SEPA)

- Adaptation Scotland :: Climate Trend tool

- Independent-Assessment-of-UK-Climate-Risk-Advice-to-Govt-for-CCRA3-CCC.pdf (theccc.org.uk)

- Population or community health profiles (see Home – ScotPHO)

Structure and presentation

- If the organisation exists across different parts of Scotland, the UK, or the world, consider carrying out a whole organisation climate risk assessment, in addition to more local or business area risk assessments. This allows for a clearer understanding of the differences in risk across the business and therefore the change in potential priorities for different areas of the business.

- Consider who will be using this data. What considerations would be helpful for them? How can results be displayed in a usable format to ensure the outcomes are included easily in future planning. For example, a land-based organisation who relies on maps and spatial data might try and display the results spatially or in a manner that can be integrated with current mechanisms for planning.

Communication and buy-in

- Ensure outputs are communicated in easy to understand and meaningful ways for stakeholders. The information gathered needs to be usable across the organisation and so should appeal to different audiences. Consider accessibility requirements, in particular for versions designed for the general public.

- Consider providing headline summaries for different areas of the organisation to ensure they can understand the key messages for their business area.

- Keep communications engaging – risk may not be the most exciting subject for everyone.

- Ensure senior leaders are well versed on the main risk areas so they can communicate these to their teams.

- Ensure there are relevant risk owners that are across the organisation. Ownership of climate risk should not only fall to climate change or environmental management professionals, as the whole business plays a part in adaptation.

- Ensure climate risks are included in or inform the organisational risk registers.

6.4.6 Adaptation strategy and planning

6.4.6.1 Developing a strategic approach to adaptation planning

Public bodies' risk assessment outcomes are part of the foundation to developing an adaptation strategy and action plan. Adaptation is a long term, movable challenge that requires strategic, flexible, implementation and planning to achieve outcomes.

Developing an adaptation strategy and plan is not an exercise for individual staff members to do in isolation. To ensure an adaptation strategy and plan are holistic and inclusive, there is a need for bottom-up approaches. Public bodies should assess which parts of the organisation might be impacted by climate hazards, who might feed into strategies and plans, and who might be key to delivering adaptation.

Adaptation strategies should set out what future scenario the public body is planning for and why. It should contain flexibility to allow movement between shifting scenarios and should lay out residual risks, i.e. acknowledgement of risks associated with tipping points and uncertainty.

Public bodies should consider how their adaptation strategy fits in within the wider policy and adaptation strategy framework. Linkages should be made with strategy areas such as the Climate Change Plan, Economic Strategy, National Flood Resilience Strategy, Biodiversity Strategy, and Scotland's National Adaptation Plan (SNAP). If public bodies are a named delivery partner in SNAP, these deliverables must be included in a public body's adaptation strategy.

The following is a guide to considerations public bodies should make while developing their adaptation strategy and plan:

Set the framework

- Consider scenario planning or an adaptation pathways approach. Considering incremental changes allows the organisation to take the appropriate action for the relevant timescale. If a tree is planted now that takes 60 years to mature, one should ensure that consideration is given to the future climate it will exist in, and factor these into current decisions. It is important to remain flexible with adaptation pathways to ensure the organisation can be reactive to changes in circumstances or science.

- Be explicit and transparent in your assumptions and basis for decision making.

- Consider the asset type and the maintenance or replacement cycles. Is it a one off or are there going to be opportunities to adapt further in the future? For example, if you know you are building a bridge now but will be replacing it in 2070, you perhaps don't need to ensure it is fully adapted to a 2070 future; however you may still want to build in some flexibility.

- What is the expected lifetime or timescale you expect the adaptation to be effective over?

- Build in future check points to interrogate how real-time events are playing out against scenarios and utilise adaptive approaches.

- Demonstrate the scale of the transition challenge.

- Establish thresholds for key risk areas that show when vulnerabilities increase and when adaptation action is required.

- Develop response plans for reacting to current and future climate hazards.

- Develop contingency plans for catastrophic events in your organisation.

Whole systems approach

- Explore stacked hazards and risks and consider worst case scenarios and extremes in climate hazards.

- Adaptation, mitigation, and nature restoration goals all need to speak to each other: be aware of potential conflicts in decision making and planning.

- Consider your organisational position in a wider context – what systems are you part of? Will your adaptation plans impact others? Consider testing plans with external stakeholders to ensure cohesive, place-based action is taken.

- Are you dependent on others internally or externally to take the required action?

- Identify elements or pressures in the system which are working against the overall strategy, plan, or goal. Consider these along with the points of greatest leverage where interventions will make most difference.

- Consider opportunities for additional benefits such as improved public health or biodiversity.

- Resilient systems build in diversity, complexity, connectivity, redundancy and flexibility. Ensure these are held at the foundations of your strategy.

- To avoid maladaptation, you need to explore bottom-up approaches to adaptation, and assess potential unintended consequences of interventions. Interventions may impact differently on different population sub-groups.

- Incorporation of bottom-up approaches into core documents is instrumental. It sets the tone for potential projects, emphasising inclusivity, equity and shared responsibility. When communities and stakeholders perceive adaptation projects as just and fair, it diminishes the likelihood of maladaptation and resistance.

Implementation

- Make use of maintenance windows to implement adaptation action. Ensure flexibility and modularity is built in and lock-in is avoided.

- Consider 'Theory of Change' in your approach to Implementation and or implement a change process that includes interim goals that you can more easily monitor.

- Ensure consideration is given to cultural, behavioural and social factors that may act as a lever or barrier to change.

- Ensure people from across the organisation are involved in the strategy and planning stages to ensure buy-in and ownership.

- Consider what information is required to inform important future decisions and make it available and understandable.

- Prioritise actions and align outcomes. Taking a whole systems approach should allow delivery of multiple outcomes and sharing resources.

- Ensure financial planning is carried out and supports your action plan. Explore mechanisms for financing your plan. Sniffer has developed guidance and case studies on financing adaptation through the Adaptation Scotland programme.

- Communicate good news stories and share best practice to increase organisational knowledge, buy-in and ownership.

- Integrate robust mechanisms to evaluate the potential consequences of adaptation initiatives. This approach decreases the risk of maladaptation and ensures that strategies are not only well intentioned but also effectively executed, benefitting both the environment and communities. Prioritising the needs of communities, rather than imposing projects upon them, will ensure more effective and equitable outcomes.

Monitoring and reporting

- Consider how you will assess whether adaptions efforts are matching the adaptation plan and the requirements.

- Build in future check points to interrogate how real-time events are playing out against scenarios and utilise adaptive approaches.

- Understand what data you need to show the link between service performance, how climate change impacts that, and how successful adaptation actions are in maintaining service levels.

- Develop a mechanism for keeping tabs on adaptation action across the organisation, and how these align with SNAP3 – this will make reporting easier.

- Where possible gather data on money spent in responding to climate related incidents (e.g., floods, landslip) to gather more intelligence for business cases on adaptation and financing them. This can be compared to the cost of implementing adaptation measures. Further guidance and case studies on business case development and economic models for adaptation interventions can be found on the Adaptation Scotland website.

A Monitoring and Evaluation framework was published alongside SNAP3.

When assessing how best to monitor their adaptation action, bodies may find it helpful to look at the national monitoring indicators, and consider whether these could also be useful at local or organisational level, in an adapted form.

For example (these are intended to be illustrative only and are not exhaustive):

(C5) Culture and historic environment: Scotland's historic environment is preparing for a future climate, and the transformational power of culture, heritage and creativity supports Scotland's adaptation journey.

Example organisational indicators for a public body that owns historic buildings as part of its estate (e.g. a body may own traditional listed buildings in a city centre):

- Proportion of historic buildings which have been climate risk assessed

- Proportion of historic buildings for which a site-specific adaptation plan has been developed.

(PS4) Transport system: the transport system is prepared for current and future impacts of climate change and is safe for all users, reliable for everyday journeys and resilient to weather-related disruption.

Example organisational indicators for a local authority responsible for maintaining the road network (excluding trunk roads and infrastructure under the responsibility of Transport Scotland):

- Proportion of A roads which require close monitoring

- Proportion of B roads which require close monitoring

- Proportion of A roads which may require maintenance

- Proportion of B roads which may require maintenance

- Proportion of road bridges which have been climate risk assessed

- Proportion of road bridges which may require maintenance.

(B1) Increasing business understanding of climate risks and adaptation action: businesses understand the risks posed by climate change and are supported to embed climate risks into governance, investment, and operations, and are collaborating on effective adaptation action.

Example organisational indicators for a public body that awards grant funding to businesses:

- Proportion of businesses in receipt of grant funding monitoring climate related risks

- Proportion of businesses in receipt of grant funding reporting taking action to adapt to the effects of climate change.

Options appraisal

Deciding what adaptation actions to take can be overwhelming, particularly with the uncertainties of future projections. However, it is important not to succumb to decision paralysis.

In order to make informed decisions about what adaptation actions will be included in adaptation plans, public bodies may consider carrying out an options appraisal. Below is some guidance on considerations to make during an options appraisal:

- Select assessment criteria relevant for your organisation: these will depend on your organisational context and situation. Potential factors to assess against include:

- Resource availability – are there sufficient human, financial or physical resources for this option to be undertaken?

- Organisational feasibility – how likely is it that the option would be supported and successfully implemented in your organisation? To what extent does it align with wider organisational priorities or objectives?

- Efficiency – how effectively will the option address climate impacts

- Costs – what are the up-front costs, upkeep and maintenance costs and are there are non-economic (i.e., social and/or environmental) costs?

- Co-benefits – Are there wider, additional health and wellbeing, equity, social, economic, and environmental benefits or mitigation benefits?

- Decision scale – can your organisation make or implement this option, or would it require buy in from other organisations or higher level of governance or decision making?

- Level of risk– is it low regret, no regret or win-win?

- Flexibility – can you alter the action in light of new information?

- Timing or urgency – would the option be best implemented now or in the future?

- Climate Justice – how does the option affect vulnerable groups or individuals?

- Unintended Consequences – what knock on implication might this action have?

- This may require hosting a workshop or meeting to bring together relevant department heads or key decision makers to get their feedback.

- If appropriate, use decision support tools, such as:

- Economic appraisals

- Cost benefit analysis

- Cost effectiveness analysis

- Multi criteria decision analysis

- Adaptation pathways assessment

More detailed guidance can be found in The Green Book: Central Government Guidance on Options and Appraisal and the supplementary business case guidance for projects and programmes.

It is important to remember that there is no final state to adaptation. Once strategies and plans are complete and action has been taken, this does not signify the end of the journey. Public bodies will need to periodically review strategies, plans, actions, and capabilities to ensure climate adaptation and resilience is maintained.

6.4.6.2 Financial planning for adaptation

In order to deliver value-for-money spending and reduce future losses resulting from climate change it is important that public bodies consider climate risks as part of long-term financial planning.

The cost of damages resulting from climate impacts are significant. Public bodies should firstly seek to understand potential costs associated with climate impacts on their organisation. The Climate Change Committee's Monetary Valuation of Risks and Opportunities in CCRA3 offers details on the costs of climate change impacts. The Scottish Fiscal Commission's Fiscal Sustainability Perspectives: Climate Change report may also be of help.

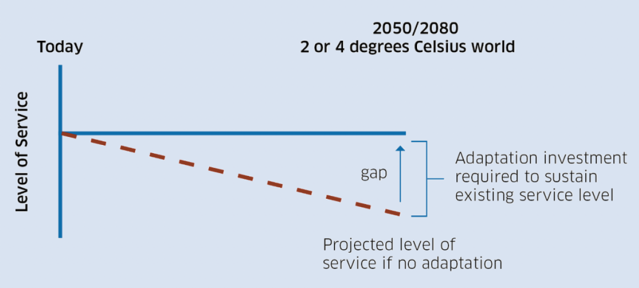

With the impacts of climate change already felt, the cost to maintain current service levels are increasing. Public bodies delivering essential services should develop an understanding of their baseline service levels, the impacts climate change will have on these and the investment required to maintain current service levels in the changing climate. It is advised however, that all public bodies should consider this.

Public sector example:

Scottish Water - Sustaining services in a changing climate

Adapting infrastructure to cope with the challenges of climate change is a complex issue with infrastructure. Scottish Water is considering the implications of climate change in terms of the level of services provided by its infrastructure today, and the way in which this will be impacted by climate change over the next 25 years. This covers issues such as the hydraulic capacity of its networks, the balance between water resources and customer demand, and the increased risk to the integrity of its assets.

This enables Scottish Water to get a perspective on the adaptation requirements and costs to sustain today’s level of service in a climate change future. This is important to enable the financial impact of climate change to be reflected in strategic investment planning. A simple model of this approach is shown below in figure 18.

Figure 18: Adaptation investment to sustain existing service levels

An example of this in practice is the service implications of more water pipe bursts. Scottish Water has identified a risk that there will be more bursts in the network in the future as soil moisture levels change, the ground moves and more bursts occur. If the rate of mains repair and rehabilitation is not increased there will be a deterioration in service and more customers may be at risk of service interruptions. It is possible using this approach to estimate how much Scottish Water may need to spend in the future to sustain today’s service levels.

The Climate Change Committee have outlined an additional investment need (across public and private sources) of £10 billion per year this decade to help improve the UK's preparedness for climate change [40]. Increased investment will be needed to respond to climate impacts and public bodies should engage in preventative spend, whereby there is a recognition that early, preventative spend will save money in the longer term. Early, preventative spend in adaptation has been shown to save money in the longer term – with benefit-cost ratios ranging from 2:1 to 10:1, i.e., every £1 invested in adaptation could result in £2 to £10 in net economic benefits[41].

To support the mobilisation of additional resources, public sector organisations should develop an investment plan for climate adaptation, which develops a strong business case for their selected adaptation actions and the funding options.

Adaptation Scotland have developed a Guide to Climate Adaptation Finance, which identifies current barriers to adaptation finance, and aims to support development of the knowledge and skills needed to successfully finance adaptation projects in Scotland. This guide will be helpful to public bodies who are looking to assess financing options for climate adaptation related projects.

The Green Book: Central Government Guidance on Options and Appraisal and the supplementary business case guidance for projects and programmes can support in undertaking value for money appraisals which account for climate change. The CCC's Investment for a well-adapted UK report may aid in conversations around adaptation investment needs and support business cases.

6.4.7 Culture, governance and mainstreaming climate change adaptation

To ensure adaptation plans are implemented and the organisation is making progress with adaptation, it will need to align with organisational priorities, culture, and resources. Adaptation and climate considerations should be mainstreamed into procedures, investment decisions, plans, and policies. Adaptation considerations should become as standardised as operational or financial considerations. Adaptation should not be viewed as an add-on or a tick box exercise. Adaptation is about taking action now to future proof Scotland, and to respond to existing climate change challenges.

Successful climate adaptation needs:

- strong leadership: this is needed from senior leaders to help prioritise and accelerate adaptation, but it is also needed from key stakeholders across the organisation, people who can act as "adaptation champions" in their business area

- governance structures to support adaptation: adaptation should fit into pre-existing organisational governance structures, but it is also helpful to set a clear structure for making decisions and providing assurance around adaptation

- committed resources: an organisation needs financial, human, physical and knowledge building resources committed to adaptation. These will likely be both internal and external

- flexibility and reflection: organisations should be continuously learning from previous experiences to help improve and adjust strategies, plans and actions and flexibility should be built into these to deal with changes and uncertainty.

Senior leadership in public bodies should prioritise and accelerate adaptation in their organisation, and should complete the Leaders' Climate Emergency Checklist.

Public bodies should explore where adaptation considerations fit into existing governance structures (e.g., risk and assurance, investment planning, business case approvals, business planning, etc.) and establish governance arrangements for adaptation.

When adaptation is seen as an add on, or where the wider organisation is not supportive of adapting to climate change, it can be difficult to know where to begin to gain buy-in and to commit resources to adaptation.

The sections below offer points for consideration on how public bodies might seek to nurture their organisation's culture to promote adaptation, identify and commit resources, gain buy-in and mainstream adaptation in business policies and processes.

Communicate climate adaptation and gain buy-in

- Take advantage of opportunities that arise from policy or legislation drivers, such as new regulations, mandates, or targets to incorporate adaptation.

- Use new publication of the Climate Change Committee's Adaptation Progress Reports and Climate Change Risk Assessments to offer key windows of opportunity to argue for advance adaptation planning

- Use formal and informal meetings, events, and workshops to engage widely across your organisation and with external stakeholders including suppliers, community planning partners and the public on the topic of and importance of adaptation. This includes everything from informal one to one discussions through to more formal presentations and awareness raising workshops.

- Consider using alternative phrases to communicate adaptation in a way that is meaningful to different stakeholders: e.g., business continuity in a changing climate, flood risk management, futureproofing, sustainable development, risk minimisation, climate justice etc.

- Start by selecting one or two relevant policy areas and identify how existing adaptation policy hooks could be used to strengthen your organisations approach to adaptation. Look for hooks such as business continuity, flood risk management, sustainable procurement, risk prevention.

- Use the Adaptation Scotland programme and Climate Outreach's values based guide to communication to find out about communicating adaptation and research the best approach for your stakeholders. If you communicate with stakeholders in a way that is meaningful for them, they are more likely to make time for discussions around it.

- Include climate adaptation in induction materials.

- Align adaptation with job descriptions to encourage responsibility and action.

- Identify potential adaptation champions who are knowledgeable and enthusiastic advocates for adaptation. Ideally the number of adaptation champions will develop over time and will include people working across the organisation in a wide range of different roles.

- Identify specific roles and or 'asks' that adaptation champions could contribute to. This could range from supporting awareness raising, joining an adaptation steering group or influencing adaptation within specific projects/ departments. Look for and create opportunities for champions to present and speak publicly about climate change adaptation at internal and external events and conferences.

- Ensure climate adaptation and risk information is made digestible, relatable, and accessible.

- Get senior management to review the Adaptation Section of the public bodies climate change duties report and take accountability for the organisation's progress.

- Create a buzz around celebrating adaptation. Use internal and external communications to celebrate staff, departments or projects that have contributed to adaptation. This will also help raise awareness of what adaptation looks like in your business and provides opportunities for shared learning.

- Embed adaptation across the organisation through cross-departmental working groups, adaptation champion networks or allocating departmental, team or individual climate change responsibilities or objectives.

Commit resources

- Identify existing relevant resources within your organisation that may be available to support adaptation work.

- Human resources - Identify job roles, teams, committees or individuals that may already be developing policies, plans or actions aligned with adaptation or who have knowledge of climate change issues and duties.

- Physical and material resources - Understand the different types of assets and what their roles in adaptation might be. Identify any assets that your organisation owns or manages that support resilience and adaptation (for example flood prevention infrastructure or estates and greenspaces that provide ecosystem services).

- Financial resources - Examine what funding is currently allocated to support work aligned with adaptation and what funding opportunities exist.

- Intellectual resources – Catalogue the skills that your organisation has access to that could help with adaptation work (for example risk managers, engineers, GIS and data analysts, community engagement, resilience practitioners, communication or environment specialists and those with facilitation skills).

- Information resources - Determine what adaptation information (including records of climate impacts) your organisation currently promotes internally and or externally and identify who holds these resources.

- Monitoring resources – Understand what resources (staff, processes, metrics and indicators) the organisation has for monitoring, evaluating, and reporting. Continue to review and update an internal resources list.

- Clearly define the short-term adaptation activities that require resourcing. Estimate the resources (for example staff time, funding, access to technical expertise) required to deliver the activity.

- Where there is a resource gap (i.e. there are not enough existing resources available to deliver the activity) identify a budget holder or funder who may be able to resource the activity and find out about the procedure for submitting a budget request. Alternatively build a business case to resource adaptation activity.

- Increase understanding of internal budget and investment cycles to see where you might approach people for budget considerations.