Climate change duties - draft statutory guidance for public bodies: consultation

Public bodies have duties to reduce greenhouse gas emissions, contribute to the delivery of the Scottish National Adaptation Plan, and to act in the most sustainable way. This consultation seeks your views on draft guidance for public bodies in putting these climate change duties into practice.

7. Implementing the third duty: acting in the most sustainable way

The third of the climate change duties set out in section 44 of the Climate Change (Scotland) Act 2009 requires public bodies, in exercising their functions, to act in the way that they consider to be most sustainable.

The National Performance Framework (NPF) is the overarching framework within which the work of central and local government, and the wider public sector, takes place. The NPF National Outcomes are aligned with the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (UN SDGs). Section 1 of the Community Empowerment (Scotland) Act 2015 requires public authorities, in carrying out their functions, to have regard to the National Outcomes.

Public bodies are, in addition, required to contribute to the achievement of sustainable development under various other pieces of Scottish legislation.

To help demonstrate compliance with the third duty, public bodies should:

- align their work to the NPF and delivery of the National Outcomes and, as best practice, to the just transition principles

- ensure that sustainable development is embedded in strategies, policies, plans and projects

- integrate a sustainable development impact assessment, or equivalent, process into decision-making processes, including financial decisions

- ensure that procurement activities are undertaken in line with relevant legislation and the Sustainable Procurement Duty

- monitor and evaluate policy implementation and outcomes against the five principles of the UK Shared Framework for Sustainable Development.

Key outcomes for public bodies will be that:

- potential policies and decisions are, before they are finalised, assessed for fairness, ecological impact, economic sustainability, whether they are based on good evidence, and whether those who are likely to be affected have had a chance to participate in the decision-making process

- activities remain within planetary boundaries, and focus on the fair distribution of both benefits and disbenefits

- good governance for sustainable development ensures participation, accountability and transparency

- the procurement process is used as an opportunity to maximise social and environmental, as well as economic, benefits; and to ensure that environmental and other harms are minimised

- they contribute, through their functions, to the National Outcomes and achievement of the UN SDGs.

7.1 Introduction to the third duty

The third of the duties set out in section 44(1) of the Climate Change (Scotland) Act 2009 is about acting in the most sustainable way. This duty may be the most important in ensuring a holistic and integrated approach to the future.

At present, there is no definition of 'sustainability' or 'sustainable development' in Scottish or UK legislation, and 'sustainable development' has often been misconstrued. Therefore, this chapter starts by providing a brief outline of what the Scottish Government considers sustainable development to mean and require before providing guidance on implementation.

The third duty is about mainstreaming sustainable development into the functioning of Scottish public bodies. Sustainability considerations should not be tagged onto business as usual activities; rather sustainability practices should be integral to the functions of the organisation. Work should be carried out in way that supports sustainable development. This is a requirement, not just of the 2009 Act, but of various other Acts of the Scottish Parliament [42].

7.2 Sustainable development: background and context

7.2.1 What is sustainable development?

The term 'sustainable development' is used to mean many different things, and to justify and bolster different perspectives and interests [43]. This section starts by taking a look at the UN definition, why it is important, the UK Shared Framework and how the principles can be implemented.

The UN defines sustainable development as development that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs[44].

"Sustainable development is how we must live today if we want a better tomorrow, by meeting present needs without compromising the chances

of future generations to meet their needs. The survival of our societies and our shared planet depends on a more sustainable world."

- United Nations[45]

7.2.2 Why might we want to develop sustainably?

When considering why we might want to develop sustainably, it can be useful to first consider unsustainable development. Unsustainable development occurs when people act in a way that has immediate or short term benefits, often restricted to particular individuals or interest groups, at the expense of the environment or other people and the wider community. For example, dumping waste chemicals into a watercourse may benefit the owner of a manufacturing business by minimising waste treatment costs, and so allow them to expand their business rapidly with the aim of generating financial profit. This may produce wider short-term benefits, such as increased local employment opportunities. However, it is likely to negatively impact on the local environment and on communities downstream. The chemicals may poison fish populations, resulting in negative impacts on the fishing industry on which other communities depend. Over time, chemicals may build up in the river sediment resulting in toxicity levels that are harmful to humans and mean that access to the area has to be restricted, or that clean-up costs are imposed on those who want to restore the waterway or utilise the area in the future.

Unsustainable development can contribute to and compound environmental degradation, pollution, social and economic inequalities and climate change. In turn, these can result in poor health outcomes, poverty, hunger and conflict over access to resources and opportunities.

Conversely, sustainable development takes a longer-term and holistic view and aims to balance economic growth, social inclusion and environmental protection [46]. Where sustainable development is achieved, everyone has access to education, health care and fair work; and use of natural resources stays within environmental limits.

7.2.3 Bringing about sustainable development – the challenges

Sustainable development is not a straightforward and easy state of affairs to bring about, in part because it requires fundamentally shifting the developmental pathway of our society as a whole. The current dominant model of societal development has taken us to a point where the ways in which we live pose a threat to our own wellbeing. In other words, the nature of many human societies that exist today cannot be sustained in their present form in the long term.

There are relatively few examples of contemporary ecologically and socially sustainable societies. There is no clear precedent for transitioning from a large scale consumption based society to one that works in harmony with the ecosystems of which we are a part, but there are many possible pathways that could be followed.

This means that there is no single or uniform 'solution' that everyone can apply. Rather we need to understand and apply sustainable development principles and thinking to our work and to developing interventions and initiatives to address human-induced ecological change and social inequity wherever we are. This will mean transformative changes to our systems, processes and way of life. Sharing information about what has been tried, what has worked, and what has not, will of course be critical, but no one size will fit all.

However, this chapter provides some information to help public bodies that are at an early stage on their sustainability maturity journey to implement the sustainable development duty. It briefly sets out reference information about the duty and about sustainable development, plus some ways in which organisations can begin to implement the duty, including how sustainable development can be put into practice, with an emphasis on avoiding conflicting policies and decision making.

Developing initiatives and interventions for sustainable development requires an understanding of the problem of unsustainable development, and a thoughtful and intelligent, evidence-based, approach that is context specific. There is no recipe or checklist that all public bodies can all follow, but rather a multiplicity of possible choices, based on the specific situation.

The two essential principles or conditions of sustainable development are set out in the UK Shared Framework for Sustainable Development, outlined in the sections below.

Further resources can be found on the SSN website.

7.3 The UK Shared Framework for Sustainable Development

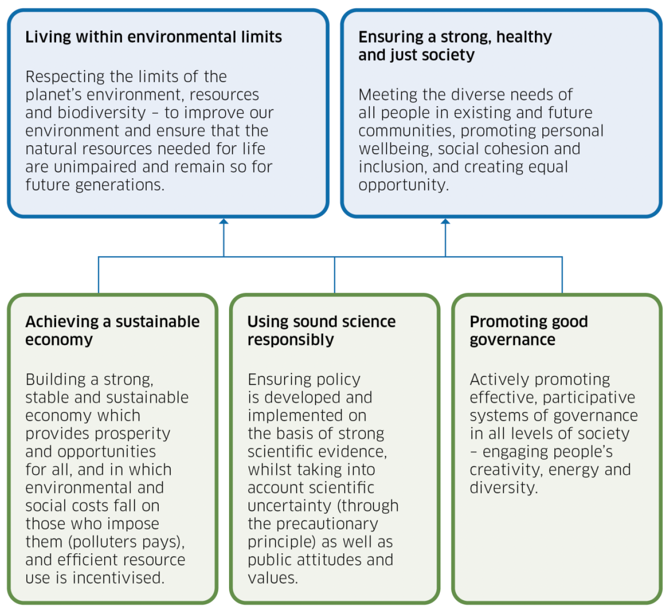

The UK Shared Framework (see figure 19) shows two essential conditions for sustainable development on the top line – living within environmental limits and ensuring a strong, healthy and just society - plus three supporting conditions:

- a sustainable economy – one which does not breach environmental limits, and whose benefits and disbenefits are distributed fairly

- sound science – ensuring that policy is evidence based

- good governance – based on participatory decision making.

Figure 19: the UK Shared Framework for Sustainable Development (2005) [47]

This framework clearly shows that sustainable development has two key goals – environmental and social, and three important means (among others) to support their achievement– a pro-social and pro-ecological economy; evidence based decision making; and participatory governance. Together these are known as the five principles. It focusses on the original problems that the notion of sustainable development was created to address: social-ecological wellbeing.

The UK Shared Framework definition is the one which Scottish Government uses, and that public bodies are encouraged to adopt.

7.3.1 Implementing the five principles

As noted above there is no checklist or recipe for sustainable development.

However, good starting points are:

- thinking about how the five principles of the UK Shared Framework can be applied

- undertaking appropriate impact assessments as outlined in section 2.2. Bodies could consider using a specific sustainable development impact assessment (SDIA) tool, such as the tool developed by the Scottish Parliament, or, if more appropriate, the health impact assessment (HIA) tool developed by Public Health Scotland. Both are freely available online, along with guidance and contact information. Both impact assessment tools are based on key factors for wellbeing and sustainable development.

Working for sustainable development requires a thoughtful and intelligent approach. In addition to using impact assessment tools, public bodies may find the following problem-solving approach relating to attitude, methods and supporting activities helpful. As best practice, bodies should embed these principles into their approach and working practices.

Attitude

Three key attitudes to solving problems and making change are:

- Curiosity: always ask 'what is going on here?' Understanding and breaking down a problem situation is essential to developing effective solutions.

- Criticality: this does not mean criticising people, it means challenging one's own assumptions and those of others. For example, 'we've always done it this way' is a common, but dangerous, assumption that a process that was instituted in a previous set of circumstances is still fit for the current set. This is not always true. For example, just because we started using lots of nitrogen fertiliser to increase crop yields as human populations expanded, does not mean that it is still a good idea: its production is energy-intensive and results in greenhouse gas emissions[48],[49].

- Compassion: to work effectively with people, it is important to interact with them in their space, and to understand their situation as best we can. Respecting and utilising their expertise, and working with them to make change in their areas is often much more effective than trying to force ideas onto them. Empowering others with knowledge, ideas and new ways of seeing the world, or a particular problem is key – when someone changes their thinking, they carry that new thinking with them, and can work out what needs to change in their domain, and perhaps more importantly, how.

Table 4 below shows how each supporting activity can help to understand and ameliorate the problem situation.

Build expertise |

Understand the problem |

Assess the causes and effects of the problem |

Identify the desired outcome |

Consider how to work towards the desired outcome |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Conversations |

Can help you develop your expertise. |

Can help you to unpack the problem situation. |

Can help you to envision what a desirable future might look like. |

Can feed knowledge and ideas into your thinking about how to address the problem |

|

Coalitions |

Allows you to tap into the expertise of others and work together on the problem |

Bring different views to the table. |

|||

Testing solutions, reflecting and refining |

Support the development of your know-how. |

What doesn't work tells you more about the problem. What works well tells you where to put more emphasis. |

|||

The following sections provide more information on environmental limits, a just society, a sustainable economy, sound science and good governance. Each section outlines the key problem of unsustainable development that the relevant sustainable development principle seeks to address. This is followed in each case by some comments on organisation-specific implementation.

7.3.2 From environmental limits to planetary boundaries

Environmental limits

An environmental limit is an estimate of how much harmful impact a particular Earth system can tolerate before it changes in a way that is a risk to humanity. For example, warming of 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels is an environmental limit beyond which the climate is increasingly likely to become a threat to human societies [50].

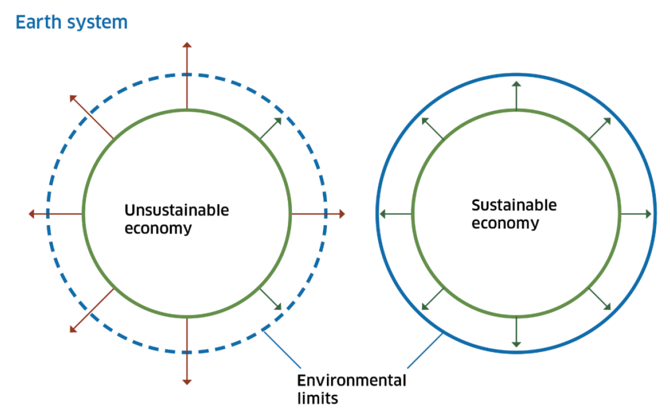

Figure 20 below compares sustainable and unsustainable economies. It visualises how an unsustainable economy breaches environmental limits (the red arrows), causing the safe and stable space for humanity to deteriorate, whereas a sustainable economy remains mostly within environmental limits (the green arrows), thereby safeguarding the ecological stability that allows us to thrive within the Earth system.

Figure 20: Environmental limits (adapted from Michael Jacobs' original included in 'The Green Economy: environment, sustainable development, and the politics of the future' [51])

This model has been refined by Earth system scientists, and we now have a much clearer idea of which environmental limits, or 'planetary boundaries' are critical to the survival of human societies.

Planetary boundaries

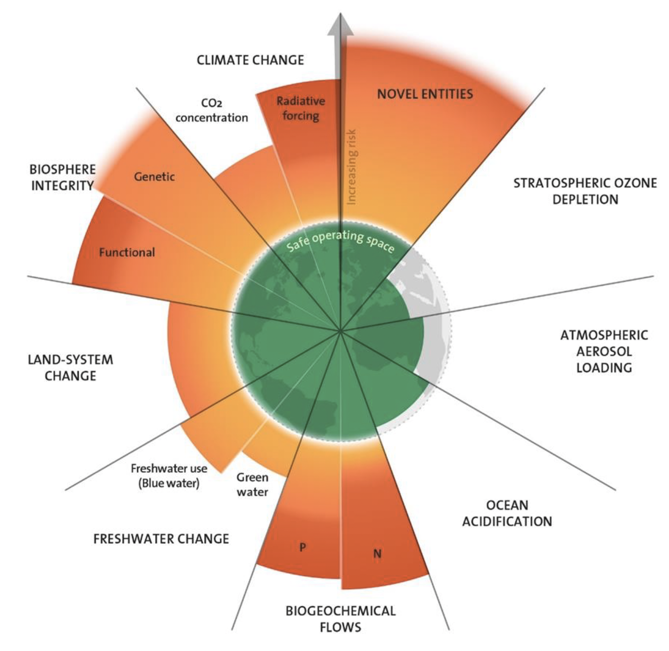

There are nine major systems and processes whose functioning and stability are thought to be critical to human societies, see figure 21 below. Transgression of the planetary boundary of any of these thresholds could tip important sub-systems, such as the monsoon system "into a new state... with deleterious or potentially disastrous consequences for humans"[52].

Figure 21: the 2023 update to the planetary boundaries [53]

The planetary boundaries model depicts a 'safe operating space' – the green inner circle – which shows the extent to which human activities can probably safely disrupt Earth systems. Beyond the safe operating space is the zone of increasing risk, which becomes higher further away from the centre of the diagram. Those planetary systems which are represented by only a green wedge, such as the ozone layer, are thought to be functioning well enough not to present a risk to human societies. However, those wedges which are orange- or red-ended show systems that have been severely disrupted, and whose altered functioning is a risk to us. It is important to note that Earth systems are interlinked, and the disruption of one of them is likely to affect others.

Further information: Planetary boundaries - Stockholm Resilience Centre

7.3.2.1 Working to minimise impacts on key planetary systems

This section illustrates how the key principles outlined in the approach above can be applied to minimise our impact on the planetary boundaries.

1. Acquire expertise: Since the publication of the first planetary boundaries model in 2009, we have learned much more about the state of the Earth system, and the extent of disruption of the nine planetary systems that are essential for the survival of human societies. More information about the global scale of the problem can be found from the Stockholm Resilience Centre.

Work has also been done to look at more local contributions to ecological disruption, e.g. by the Good Life for All within Planetary Boundaries project.

Other sources of expertise might include colleagues in the your own organisation, other public bodies, including academia, and consultants.2. Understand the problem: One route to understanding a complex problem, such as that of planetary boundaries, is to work out what its most essential components are, e.g.

- human societies depend on Earth systems, but are damaging and disrupting them

- because of this, Earth systems are changing, which may cause societal collapses[54].

3. Consider whether and how your organisation, or the public you serve, are contributing to, or are affected by the problem: Looking at the UK-level disruption of planetary boundaries on the A Good Life for All within Planetary Boundaries website, we can see that:

- per capita carbon dioxide emissions are nearly eight times higher than the planetary boundary allows for

- phosphorus use is nearly six times higher than it should be

- nitrogen use is just over eight times higher than it should be

- blue water (surface and ground water) use is less than half the threshold value

- the amount of energy we consume by using other organisms, e.g. for food, fuel, fibre, or by changing land from a state that can capture the sun’s energy for food and support food chains (e.g. a forest), to a state that does this less or not at all (e.g. cropland, or a car park) , is just under the maximum level it should be

- in addition, our ecological and material footprints – measures of our consumption – are just under two and a half, and three and a half times the maximum they should be.

Consider questions such as:

- Which of these impacts are affecting the public or organisations you serve or regulate?

- Which of them is being created in your geographical or regulatory area?

- Which do you have influence over?

- Which of them do other public bodies have influence over?

- Which bodies could you work with to bring these impacts to within safe levels?

4. Identify what needs to be done: what is the outcome you want to see? For example, the amount of nitrogen that is industrially or intentionally converted from a gas in the air to, for example, fertiliser, is eight times higher than safe levels. Perhaps we might want to see an eightfold reduction in the use of nitrogen fertiliser? Or the cessation of industrial nitrogen fixation, or of its importation?

What steps might we have to take to move towards our desired outcome? Who can help plan these steps?

5. Make a plan: which sets out how you and your organisation might support or participate in moving towards the desired outcome; which aspects of the solution are within your gift; what actions are required from others, and in what order; how you might make a space for collaboration, and bring actors together. For example, if you have responsibility for public land, such as parks or golf courses, you might want to start by checking the Scottish Government’s Principles for Sustainable Land Use established through the Scottish Land Use Strategy. You may also want to explore specific site related land management practices, such as whether nitrogen fertiliser is being used on them. If it is, your next step might be to consider and discuss alternatives with experts and stakeholders, and agree on what actions can be taken. How will you monitor progress and outcomes?

6. Reflect on, and adjust your plan as you progress: as you and your collaborators move forward with the plan, keep reflecting on what has worked, and what hasn’t. Adjust your plan based on your reflections. Reflecting together can be far more powerful than reflecting alone.

7.3.3 Social equity

As a social species, our brains are hard-wired to dislike unfairness. This helps us to cooperate, which we need to do because we are generally far less likely to survive as isolated individuals. In fact, there is significant evidence to show that more unfair societies are worse off on the whole.

For example, the Equality Trust which focusses on socio-economic inequality points to bodies of research[55] which show that:

- rates of violent crime are higher in more unequal societies[56], which would make societies less safe

- higher income inequality results in lower levels of trust, which we need for social cohesion and cooperation

- The main factor that determines both health and educational outcomes is socio-economic status[57]

- Obesity rates are significantly higher in more unequal societies. The US, for example, has one of highest rates of inequality and also obesity

- Income inequality is linked to higher prisoner rates and harsher punishments.

These issues of inequality affect societal functioning and collective and individual wellbeing. Research carried out by two of the founders of the Equality Trust shows that poor outcomes (in states with high monetary incomes), are more related to inequality than average income [58] . Societies where income is distributed more equally are more beneficial for their members, and score better on an index of health and social measures. Unequal societies, even those with higher average incomes, scored worse. There is no clear relationship between income levels and health and social problems. This evidence suggests that the pursuit of equality or equity might be more effective in improving social function and individual health than the pursuit of income growth.

In order to develop into societies that are not creating the conditions likely to lead to their own collapse, and which function well because individual members are well, as are their relationships with each other, our activity should remain within planetary boundaries, and should focus on the fair distribution of both benefits and disbenefits.

To achieve this, we need a sustainable economy, and participatory decision making based on sound science (see section 7.3.5, below).

7.3.3.1 Working to maximise social equity

You can follow or adapt the problem solving method outlined in section 7.3.1 above to focus on social equity, and any of the following three supporting principles for sustainable development. The key is to start by understanding the problem; to work through developing and trialling solutions or interventions; to reflect on results or findings; and refine methods.

In relation to social equity, or fairness, there are a few key things to consider in relation to understanding the problem: 1. A good way to think about equity or fairness is in relation to people's capability to meet their fundamental human needs (see figure 22 below). A fair society would be one which enables its members to acquire the capabilities they need in order to meet their needs. For example, one of our fundamental needs is nutrition, so perhaps there are actions we can take to ensure that the people who we serve:- have access to nourishing food

- can acquire the knowledge and skills they need to obtain and prepare nourishing food

- have access to the tools they might need to do this.

Some examples of how this has been used include:

- in evaluating public health interventions[60]

- to understand multidimensional poverty[61]

- to support housing policy[62]

Structural inequity can be compounded by lock-in. For example, if we replace public transport networks with roads, people may have no alternative but to become car users. If they aren't able to do this, then they are less likely to be able to access opportunities that are further away than people who have access to a car.

One of the most important actions we can take for sustainable development is to assess potential policies and decisions before they are finalised for fairness, ecological impact, economic sustainability, whether they are based on good evidence, and whether those who are likely to be affected have had a chance to participate in the decision-making process. You can do this by using an appropriate impact assessment tool (see section 2.2).

7.3.4 Wellbeing and a sustainable economy

7.3.4.1 What is wellbeing?

Often wellbeing is assessed (and therefore understood) through self-reported life satisfaction or 'happiness'. This is referred to as 'subjective' or 'hedonic' wellbeing because it is reliant on the subject's perspective. While this type of data can be relatively easily gathered, it can be problematic for a number of reasons, including that:

- it is natural and healthy to sometimes feel less happy, for example grieving is an important psychological process

- individuals and cultures can vary in how they might choose to rate their mood

- in itself, it doesn't provide much information to support policy development.

A probably more informative approach to understanding wellbeing is 'objective' or 'eudaemonic' wellbeing, which is about the extent to which people are able to satisfy their fundamental human needs.

7.3.4.2 What are fundamental human needs?

It has long been understood that human activity is motivated by the urge to meet our needs. For example, if we need hydration, we feel thirsty, which drives us to look for something to drink. It is thought that there is a set of fundamental needs that is almost universal amongst humans. Although there are various ways in which these needs can be understood and categorised, perhaps the most straightforward is that humans have:

- biological needs, such as clean air to breathe, food, shelter and warmth

- social needs, such as belongingness, participation and love

- self-actualisation needs, such as expressing one's true nature [63] .

The objective wellbeing approach is therefore more policy-relevant because a well-functioning society would support the capability of its members to meet their needs. For example, to meet our need for clean breathable air, society must ensure that air pollution is properly controlled.

At a wider level, to meet our biological needs and enable us to meet our social needs, we require a well-functioning ecosphere (section 7.3.2). To meet our social needs, we require a well-functioning society which, as outlined above (section 7.3.3), would be one in which benefits and disbenefits are fairly distributed. A wellbeing economy could be described as one that operates to equitably meet our fundamental human needs within planetary boundaries.

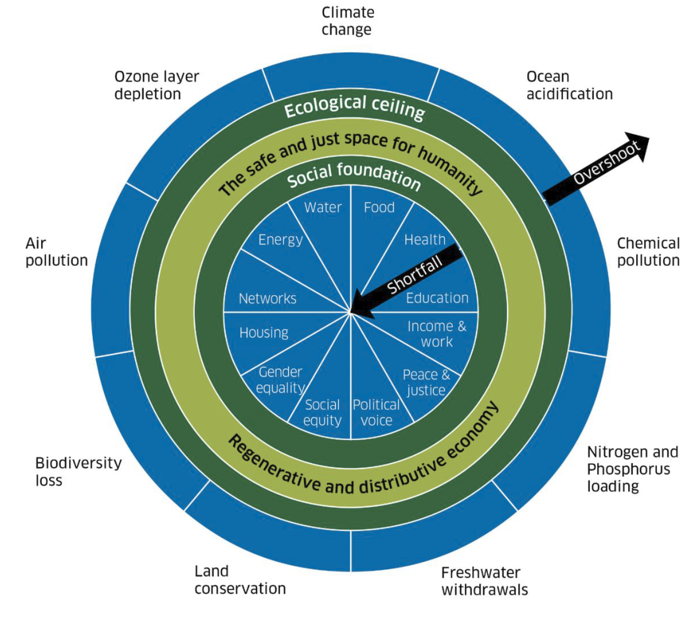

Raworth's 'doughnut' model of a sustainable economy [64] (figure 22 below) illustrates this, depicting not just a safe operating space for humanity, but a safe and just one – the green doughnut-shaped ring in the diagram. The ring has a dark green ecological ceiling, representing the planetary boundaries that we must not breach if we aim to maintain contemporary societies. Below this is a dark green social foundation, which represents human needs and which we must not go below for an equitable and well-functioning society.

The doughnut model mirrors the UK Shared Framework for Sustainable Development (figure 19) in showing that human wellbeing depends on ecological integrity (environmental limits) and social equity (a strong, healthy and just society).

As the nature of our economies and governance systems dictate how we meet our needs, and the extent to which we disrupt planetary systems in seeking to do so, a transition to wellbeing economies, as depicted by the doughnut model, is necessary.

Figure 22: The doughnut model of a sustainable economy (based on Kate Raworth's doughnut model of social and planetary boundaries [65])

7.3.4.3 What is a wellbeing economy?

While definitions vary, a wellbeing economy can be described as an economic system operating within safe environmental limits, that serves the collective wellbeing of current and future generations first and foremost.

It is a system that empowers communities to take a greater stake in the economy, with more wealth generated, circulated and retained within local communities, while protecting and investing in the natural environment for generations to come.

It provides opportunities for everyone to access fair, meaningful work, and values and supports responsible, purposeful businesses to thrive and innovate. The approach recognises that reducing inequality and improving the lives of citizens through a human rights-based, social justice approach can also make the economy more resilient.

It supports the transformations in our economy and society needed to thrive within the planet's sustainable limits and capitalises on the opportunities this creates for improving people's mental and physical health and wellbeing, tackling inequalities and supporting green jobs and businesses.

Traditional economic metrics such as Gross Domestic Product (GDP), Gross Value Added (GVA), productivity and headline employment rates are regarded as important indicators of how an economy is functioning and contributing to economic objectives. However, it has been widely acknowledged that these metrics do not provide a full picture of the whole economy, as they do not recognise unpaid work, and do not distinguish between economic activity which contributes positively to the health and wellbeing of people and the natural environment, and that which has negative impacts on wellbeing outcomes. They also fail to reflect inequalities within the economy. The Scottish Government's Wellbeing Economy Monitor tracks broader economic outcomes beyond GDP on issues such as health, equality, fair work and the environment, and helps us assess Scotland's progress in building a fairer, greener and more prosperous economy.

7.3.4.4 Working towards a wellbeing economy

Models and frameworks for building a wellbeing economy vary, though they share some key aspects and goals. A broad range of environmental sustainability issues should be considered, including opportunities for protecting and restoring natural assets, reducing greenhouse gas emissions and transitioning to a circular economy – also recognising the range of wider benefits this can create for improving health and wellbeing, tackling inequalities and supporting green jobs and businesses.

The Scottish Government's goal is to help people live happier and healthier lives with higher living standards, to help businesses boost profitability, and build a more resilient Scottish economy that promotes the wellbeing of all Scotland's people. Our approach to building a fair, green, growing economy is informed by our Wellbeing Economy Expert Advisory Group and through our international engagement with the Wellbeing Economy Governments (WEGo) network. Key features of the approach include:

- taking an open, transparent, participatory approach to developing strategy and policy, involving those impacted by the policy, empowering citizens and diverse communities

- setting a clear purpose and vision for economic policy and activity, focused on collective wellbeing

- establishing clear outcomes and metrics for measuring if and how our economy is delivering wellbeing for people, place and planet

- taking an evidence-based (qualitative and quantitative), whole-systems view to understand the key drivers of wellbeing outcomes, how they interrelate, and which have the greatest impact

- adopting a preventative approach by focusing interventions on upstream parts of the system to avoid negative impacts on outcomes downstream and building long-term resilience

- embedding inclusion, equality and fairness into economic policy from the outset, working with and empowering communities and citizens to gain a greater stake in the economy and removing barriers to participation

- monitoring, evaluating and encouraging continuous learning, being open to innovative and experimental approaches.

The Scottish Government's Wellbeing Economy Toolkit provides a guide for local authorities and other public bodies to view the Wellbeing Economy as a system and to develop local strategies focused on wellbeing outcomes, based on Scotland's National Outcomes.

7.3.5 Sound science and good governance

These last two supporting conditions for sustainable development are interlinked.

Sound science is about ensuring that decisions are based on good evidence – the term 'science' is used in its literal sense, to mean 'knowledge', not limited to so-called 'natural' or 'hard' science. Good governance for sustainable development should be built on evidence-based decision making, which includes the evidence of lived experience, and the needs and opinions of those who might be affected. It should therefore ensure participation, accountability and transparency.

This also relates to community empowerment. Scottish Government is committed to supporting communities to do things for themselves, and to make sure their voices are heard in the planning and delivery of services.

7.3.5.1 Sound science and good governance for sustainable development

Together, the principles of sound science and good governance mean that decision-making processes (which include decisions about internal and public policy, as well as operational decisions, strategies and plans, etc.) should include:

- gathering and reviewing evidence, e.g. research, expert and public opinion, understanding relevant lived experience

- dialogue and deliberation – ensuring that people with a range of backgrounds, perspectives and experience can feed in to the process

- assessing potential impacts, and especially considering what unintended consequences could occur.

An evidence-based approach to implementation is also important, and should include:

- trialling, if possible, before full implementation, with a view to making adjustments to improve outcomes

- monitoring and evaluation, to understand what positive and negative outcomes are actually occurring; this can include ongoing engagement with those who are affected by the decision or policy

- adjusting and improving as new information becomes available – this might be from monitoring and evaluation, feedback, changing knowledge, observation of impacts, etc.

Most importantly, good governance should also seek to ensure that decision making is pro-social and pro-ecological, unlikely to contribute to the breaching of planetary boundaries, and likely to increase social equity. That is to say, that decision making across an organisation should be focussed on supporting sustainable development.

Assessing the likely impact of decisions, e.g. about buying something, in terms of how they could affect ecosystems, people, the ability of economies to meet people's needs, and whether they are based on good evidence and are likely to be well-governed, is key to this. Using existing or bespoke impact assessment tools can help with this (section 2.2 and section 4.5).

Guidance and resources on participatory budgeting can be found on the PB Scotland website. Guidance on assets transfers, for assets to pass into community ownership or management, is published by the Scottish Government.

7.4 Mainstreaming sustainable development

As noted above, the third duty set out in the 2009 Act requires relevant public bodies to carry out their functions in a way that they consider to be most sustainable, i.e. that supports sustainable development. They are also required, under the Community Empowerment (Scotland) Act 2015, to have regard to the National Outcomes, aligned with the UN SDGs, in carrying out their functions. This means that a more holistic and joined up approach needs to be adopted to integrate sustainable development thinking into all policy and decisions.

Integrating sustainable development doesn't mean 'business as usual but with more recycling and low emissions vehicles'. It means that the way in which public bodies carry out their functions supports sustainable development – rather than sustainable development being an add-on. Sustainable development principles should be embedded in the practices and functioning of the organisation.

As sustainable development concerns all aspects of societal development, it is a complex subject, and may require expert technical support. It also requires everyone to participate. A checklist approach, such as could be useful in seeking to reduce greenhouse gas emissions by listing areas where reductions should be made, is not feasible for sustainable development. This is because there are no blanket solutions that work for all situations, and most importantly, we need to make holistic decisions based on multiple ecological and societal factors. Instead, we need to change the way we think and solve problems.

7.4.1 Contributing to the NPF national outcomes

The National Performance Framework (NPF) is the overarching framework within which the work of central and local government, and the wider public sector, takes place. The NPF supports a shared way of working and asks everyone to work together to improve the lives of the people of Scotland. It aims to create a more successful country, with increased health and wellbeing and reduced inequalities, and where social, environmental, and economic wellbeing are given equal importance.

As outlined in section 2.1.1, the national outcomes are aligned with the UN SDGs, illustrated in figure 23 below.

Figure 23: the UN Sustainable Development Goals [66]

The United Nations Sustainable Development Goals

- No poverty

- Zero hunger

- Good health and well-being

- Quality education

- Gender equality

- Clean water and sanitation

- Affordable and clean energy

- Decent work and economic growth

- Industry, innovation and infrastructure

- Reduced inequalities

- Sustainable cities and communities

- Responsible production and consumption

- Climate action

- Life below water

- Life on land

- Peace, justice and strong institutions

- Partnerships for the Goals.

The Community Empowerment (Scotland) Act 2015 places a duty on public authorities to have regard to the national outcomes in carrying out their functions. Through their work, public bodies should contribute towards the achievement of the national outcomes, and in turn the UN SDGs.

Public bodies should, as best practice, ensure that decisions such as those around public finances and budgets, major expenditure, public service delivery (including the closure or cessation of existing services) and major development proposals, are assessed in relation to wellbeing, sustainable development, addressing inequalities and the needs of future generations.

7.4.2 Using the National Performance Framework

Public bodies should align their work with the national outcomes and the associated SDGs, as illustrated in figure 24.

Figure 24: Aligning with the National Outcomes

Step 1: National Outcomes and UN SDGs ‘contribution story’. Explain the linkages your work or policy area has to the National Outcomes and associated Sustainable Development Goals.

Step 2: Intermediate outcomes. Together with your partners, identify what your intermediate (i.e. policy or programme level) outcomes are.

Step 3: Priorities and planning. What do the evidence and your partners tell you about where we are in Scotland in achieving these intermediate outcomes? Where are we most falling short?

Step 4: Action plan. Based on your priorities, develop an action plan based on the evidence and a strong theory of change.

Steps 5 and 6: Implementation, evaluate and report. Monitor and evaluate the implementation of your activities as robustly as possible.

The NPF website provides resources and advice on outcomes working, including examples of how public bodies are using the NPF and aligning their work to it.

7.4.3 Sustainable development thinking

There are four main interlinked components to sustainable development thinking:

- Knowledge – an understanding of how ecological and social systems function, and how they are interlinked

- Ontology (world view) – that is systemic and understands that humans are one species among countless others, entirely dependent on them for our survival and wellbeing

- Cognition (thinking) – fostering ways of thinking that seek to understand and address the root causes of problems, that are long term, deep, and broad, as well as holistic and systemic

- Practice – practitioners of specific disciplines, such as Planning or public health, are best placed to use their expertise to develop solutions to problems in their domain, although collaboration with sustainable development experts may be necessary to ensure those solutions support sustainable development.

Knowledge

Sustainable development is a highly complex matter, and our current unsustainable development is a 'wicked problem'. Wicked problems [67] are multifaceted, can be contradictory and changeable, and often feature complex interdependencies. There are no clear or simple solutions, and very little in the way of precedents to draw on.

Sustainable development relates to all aspects of human life, and therefore requires a trans- (or post-) disciplinary approach – decisions should be made based on several factors, rather than just one such as monetary price or convenience, and considered from a number of angles. Although we are generally taught and trained to carry out our work in a certain way, depending on our profession, we can no longer afford to make decisions from one point of view, or take only one set of considerations into account, e.g. health and safety, without thinking about wider impacts.

For example, using personal protective equipment to protect workers from harmful chemicals may provide individuals with protection from direct exposure but:

- will toxic substances still end up in the environment?

- how will they affect ecological functioning?

- where will they end up – in water sources, in the air or in soils?

- how would this affect us in the long term?

Integrating sustainable development thinking so that people apply it routinely in their day to day work requires expert support and advice. Fortunately, there is considerable expertise that exists within the Scottish public sector, civil society organisations, academia, and among other practitioners, like consultants.

Worldview

A holistic big picture understanding of the world is essential, as well as the understanding of how one's own work fits into it. This can tell us which levers we need to use to support sustainable development, which of those are within our reach, and which we might need to collaborate with others to use. To foster a holistic perspective, sustainable development knowledge is necessary, and support to think beyond the boundaries of one's own work, to understand how it connects to that of others, and what effects it might have.

Thinking

We are often trained to think in linear, mechanistic ways. Supporting staff members to think about the consequences of decisions, including whether we should carry on doing things the way we always have, and how that might affect society and ecosystems at various different levels, including spatial and temporal, can help lead to integrated solutions and policy coherence, which are necessary for development to shift to a sustainable pathway.

An integrated solution is one which depends not on trade-offs, but on win-win-win solutions, which can usually only be arrived at by resolving the root cause of a problem.

Practice

Sustainable development knowledge, worldview and thinking take time to internalise. Nevertheless, they can support the realisation of individual and collective agency [68] – the power one has to choose to act with purpose. Pro-sustainable development action across an organisation can result in real change, especially if colleagues are empowered, mandated and supported to decide how to integrate sustainable development considerations into their work.

7.4.4 Impact assessment

Addressing a wicked problem like unsustainable development is highly complex. One type of tool that can support more pro-social and pro-ecological decision-making is impact assessment that takes a holistic, integrated approach. The impact assessment process should provide much needed space and time for colleagues to think together, deliberate, and consider an issue from a wide range of angles, which should support better thought-out solutions.

Impact assessments are outlined in section 2.2.; and chapter 3 provides further examples around equality impact assessment. The topic supplements will, in due course, provide further information and examples, including Public Health Scotland's health impact assessment and the Scottish Parliament's sustainable development impact assessment. Both these examples require the participation of sustainable development or public health experts, ideally as facilitators.

7.4.5 An integrated approach to the three duties

The climate system and the biosphere are believed to be the two core, mutually dependent, systems essential to the stability of the Earth system as a whole. Indeed each ecological system, from a tiny local ecosystem – say a small woodland - to the planetary systems that circulate nutrients around the globe, or maintain our protective atmosphere, is inextricably intertwined with bigger, smaller and neighbouring systems [69].

While working to remedy a problem in one area, it is therefore important to consider and avoid or minimise harmful effects in others. For example, wind energy forms an important part of plans to decarbonise grid electricity. However, ill-considered development of windfarms on deep peat can cause widespread, long term damage and high greenhouses gas emissions, so that 'the payback time is calculated to be longer than the lifetime of the windfarm.' [70]

Not only can poorly thought out initiatives cause ecological damage, they can also harm other human societies. For example, 'green colonialism' has recently been brought to light, whereby the efforts of wealthy countries to acquire the minerals and metals they 'need' to reduce their harmful impacts is damaging societies which live in older ways, sometimes outside the global capitalist economy [71] .

Ensuring that broad holistic social-ecological thinking is brought to bear on problem solving, rather than basing action only on the comparison of calculated GHG emissions is more likely to help to minimise and avoid causing unintended harms.

7.5 Multiple duties and compliance

Public bodies are likely to have a number of statutory duties. In some cases, these may appear to be conflicting. However, the 2009 Act states that public bodies must carry out their functions in a way that supports mitigation of, and adaptation to, climate change, and act in way that supports sustainable development. Other duties, which confer other functions on public bodies, should be carried out in ways which support mitigation, adaptation and sustainable development.

For example, where there are duties on 'sustainable economic growth' this should be interpreted in a way that supports the mitigation of, and adaptation to, climate change.

7.5.1 Sustainable procurement duty

Public procurement in Scotland aims to use collective spending power to deliver sustainable and inclusive economic growth. The Public Procurement Strategy for Scotland 2023-2028, published on 27 April 2023, sets out that this spending power can be used to make Scotland a better place to live, work and do business. How goods, works and services are procured should promote inclusive economic growth, create fair opportunities for all, and accelerate the just transition to a net zero economy.

Legislation governs how Scottish public bodies buy goods, services and works. The sustainable procurement duty in the Procurement Reform (Scotland) Act 2014 requires that before a contracting authority buys anything, it must think about:

- how it can improve the social, environmental and economic wellbeing of the area in which it operates, with a particular focus on reducing inequality

- how its procurement processes can facilitate the involvement of SMEs, third sector bodies and supported business

- how public procurement can be used to promote innovation.

It requires a contracting authority to be aware of how its procurement activity can contribute to national and local priorities and to act in a way to secure this.

Procurement spend should be considered in this context, before the start of the formal procurement process, by all those involved, including: external stakeholders, budget holders, commissioners and policy leads.

A range of guidance and tools has been developed to assist public bodies in their sustainable procurement activity, including statutory guidance on the sustainable procurement duty, and the sustainable procurement tools.

Further guidance and resources will be provided in the relevant supplement in due course.

7.5.2 Sustainable land use

Scotland's Land Use Strategy sets out the long-term vision for sustainable land use in Scotland:

“A Scotland where we fully recognise, understand and value the importance of our land resources, and where our plans and decisions about land use will deliver improved and enduring benefits, enhancing the wellbeing of our nation.”

How land is owned and managed is fundamental to how we live in Scotland, and is a platform on which many of the national outcomes can be delivered. The climate and nature emergencies cannot be addressed without changes to the way that land is used and managed. Land offers opportunities to help meet net zero targets, to adapt to climate change and restore nature.

Public bodies with landholdings or an interest in land should look to form or join Regional Land Use Partnerships (RLUPs). RLUPs are intended to help local and central government, land owners, communities and other stakeholders to work together, to find ways to optimise land use in a sustainable, fair and inclusive way, with the aim of meeting local and national objectives, and helping achieve national climate change targets through changes to land use and good land management that supports a sustainable future.

The Land Rights and Responsibilities Statement takes a human rights approach and contains six principles that should underpin every decision made about land, including greater transparency, responsible exercise of land rights, and greater engagement and collaboration between those making decisions and those affected by such decisions. It lays out a vision where all land contributes to a sustainable and successful country, supports a just transition to net zero, and where rights and responsibilities in relation to land and natural capital are recognised and fulfilled.

Guidance on engaging communities in decisions relating to land has been published by the Scottish Land Commission.

7.6 Sector specific approaches

NHS Scotland

A policy for NHS Scotland on the climate emergency and sustainable development (DL (2021) 38 was issued by Scottish Government to Health Boards on 10 November 2021. It sets out the aims and associated targets relating to sustainable development and climate change for Health Boards to work towards. It takes account of relevant wider Scottish Government policies and existing statutory duties.

The NHS Scotland Climate Emergency Strategy 2022-2026 sets out actions directed at achieving the aims and targets in DL (2021) 38. It sets out actions which will either begin between 2022 and 2026, be completed during that period, or are already underway and will continue during that time.

The national NHS Scotland Sustainability Action Programme was established in 2022-23 to introduce a defined, structured and timebound approach to the delivery of Once for Scotland actions with the intention of supporting NHS Boards to implement the strategy locally. The programme is delivered by NHS Scotland bodies and the Scottish Government in collaboration with other organisations including NatureScot, Zero Waste Scotland and Scottish Water.

Education: Sustainable Learning Settings

Scotland's learning for sustainability action plan 2023 to 2030, Target 2030: A movement for people, planet and prosperity, aims to build an inspiring movement for change so every place of education for learners aged 3 to 18 years becomes a Sustainable Learning Setting by 2030. Local authorities and other public bodies involved in places of education should integrate the 2030 commitment into their improvement plans, strategic plans, curriculum frameworks, corporate plans and activities.

The concept of sustainable learning settings includes the curriculum, culture, community and campus and is about every aspect of the learning context. It is about what and how students learn, how the setting manages its physical environment and resources, how staff and learners relate to each other, how they work with their local community and how they reach out to the wider world. In a Sustainable Learning Setting staff will be supported to build their confidence, develop their practice and access training and support. Learning, teaching and assessment will provide rich learning opportunities for children and young people; opportunities that are rooted in real life, with access to interdisciplinary and work-based learning which prepares learners for the future. Improvements to buildings and grounds and links to the wider community will also flow from this whole-setting approach.

Further and Higher Education

The SFC's Outcomes Framework and Assurance Model sets out the expectations of colleges and universities in return for the funding they receive, and the mechanism by which SFC will engage with colleges and universities to monitor delivery against outcomes. Net zero and sustainability is a cross-cutting outcome across nine themes (seven for colleges), setting the expectation that institutions mainstream and embed net zero and sustainability into all aspects of their operations: Outcomes Framework and Assurance Model - Scottish Funding Council

EAUC Scotland's mission is to inspire, empower and support leadership and collaborative action for sustainability across the Scottish further and higher education (FHE) sector. Its 2024-25 programme (EAUC Scotland Programme 2024-2025 | EAUC) builds upon previous outcome agreement work with the SFC, and on behalf of Scottish further and higher education institutions.

The Quality Assurance Agency for Higher Education (QAA) has published guidance intended to help UK higher education institutions embed Education for Sustainable Development (ESD) within their curricula. ESD aims to support all learners to envision and work towards a world that recognises the interdependencies between the environment, social justice and economic wealth, acknowledging that resources are limited and that they provide the foundation for our societies and the economy.

Guidance and information on opportunities for collaborative working can be found on the QAA website (some information is restricted to QAA members).

Internationalisation and sustainability

Scotland welcomes international students, staff, and researchers, recognising the important and valuable contribution they make to the Scottish economy, our educational environment, our society, and our communities.

Our universities and colleges are globally respected. The National Strategy for Economic Transformation (NSET) highlights that Scotland has more top universities per head of population than any other country in the world and is in the top quartile of OECD countries for Higher Education Research & Development. As highlighted by the College Development Network's International Ambitions Report, Scottish colleges successfully export, engage, and excel overseas. They welcome students from over 130 countries, hold partnerships from Azerbaijan to Vietnam and attracted more Erasmus+ funding per capita for their staff and students than the rest of the UK. Colleges act as 'enablers' of internationalisation given their responsibility to reflect the needs of industry, government, and internationally competitive skills.

Our universities and colleges provide world class education, skills training, and overseas collaborations that bring education to developing countries. This allows Scotland to work towards the UN Sustainable Development Goals by providing education, research, and innovation in other countries. Such initiatives are an important part of our overall inclusive, welcoming, and diverse educational environment, which actively promotes knowledge transfer and shared experience between nations.

However, internationalisation strategies and operations can run outside of, and in tension with, institutional sustainability policies and commitments.

Universities and colleges should therefore review internationalisation strategies and operations and explore opportunities for improving the environmental sustainability of institutional practices.

Contact

Email: climate.change@gov.scot

There is a problem

Thanks for your feedback