Climate change duties - draft statutory guidance for public bodies: consultation

Public bodies have duties to reduce greenhouse gas emissions, contribute to the delivery of the Scottish National Adaptation Plan, and to act in the most sustainable way. This consultation seeks your views on draft guidance for public bodies in putting these climate change duties into practice.

5. Implementing the first duty: reducing emissions

The first of the climate change duties set out in section 44 of the Climate Change (Scotland) Act 2009 requires public bodies, in exercising their functions, to act in the way best calculated to contribute to the delivery of national emission reduction targets, i.e. to reduce greenhouse gas emissions, also known as climate change mitigation. In the context of the duties, ‘targets’ means both the national five-yearly carbon budgets and the final 2045 target.

To help demonstrate compliance with this duty, public bodies should:

- develop a climate change strategy that includes net zero and other relevant targets and has regard to just transition principles

- develop and implement a carbon management plan or equivalent

- develop action plans to deliver key elements of the carbon management plan, detailing interim steps, costs, timescales and dependencies

- set up a process of monitoring and reporting, to report on performance against their targets and action plans

- ensure that mitigation actions maximise co-benefits, such as improved public health, reduced inequalities and enhanced biodiversity, and minimise unintended consequences such as maladaptation and negative environmental impacts

- undertake the above giving due consideration to their physical assets including buildings, land and fleet; their staff and service users; the services they deliver; the investments they manage; and the functions

5.1 Introduction to the first duty

To support the duty to reduce emissions, this chapter briefly sets out:

- the importance of taking action to mitigate emissions

- the net zero approach to mitigation

- decarbonisation pathways

- reducing emissions in practice – climate strategies, target setting, carbon management plans, monitoring and reporting.

It is likely for most public bodies that the majority of direct scope 1 emissions will come from heating buildings. Public bodies should make decisions about the heating systems in their buildings in line with the Local Heat and Energy Efficiency Strategy (LHEES) for their area. When installing or replacing heating systems, due consideration should be given to individual clean heating systems and the future potential for heat networks, as suggested by an LHEES. These set out zones where heat networks may present a potential decarbonisation option. Public sector buildings should be an early focus to allow exploration of opportunities for coordinated action on decarbonisation of heat, including the identification of public buildings that could act as anchor loads in any future heat network. Harder to treat buildings many benefit from this early exploration.

For some public bodies direct emissions from fleet, process emissions and fugitive emissions may also be significant. Bodies are also likely to have substantial indirect scope 2 emissions associated with acquired electricity, and potentially heat, steam and cooling.

However, the majority of total emissions will likely be indirect scope 3 emissions from the wider value chain, in particular those resulting from purchasing e.g. all of the things a public body buys in order to deliver its functions, from buildings to vehicles, and furniture to IT equipment.

It is therefore likely the key actions for most public bodies will include:

- The decarbonisation of heating systems and fleet e.g. replacing gas boilers or combined heat and power plants with air, water or ground source heat pumps, or connecting to a district heating network powered by the same.

Public bodies should focus investment in reducing emissions in those buildings that are planned to remain part of the estate in the longer term. The 'Built Estate' supplement will, in due course, set out the recommended approach to understanding future estate needs. This should be followed, so as to focus energy efficiency and clean heat investment on those buildings for which there is confidence on future need. Where a public body expects to vacate a building, improvements should be limited to those required as part of planned maintenance requirements and to meet other statutory obligations.

- Public bodies having clear long term strategies for their assets and the sustainable management of those assets. Public bodies should consider the size and location of their estate, whether it matches service requirements and future needs, opportunities for co-location of services – to maximise use and minimise waste (including emissions). This includes adapting the assets to net zero standards and making assets resilient to a changing climate.

- Replacing petrol and diesel vehicles with electric or low carbon fuelled vehicles.

- The reduction of electricity use wherever possible via, for example, improved building fabric to reduce heating demand, installation of renewables, LED lighting, and replacement of inefficient equipment with energy efficient alternatives.

- Achieving net zero will, generally, see public bodies using more electricity for heat in their buildings – particularly if they are moving to electrical heating. At the time of writing, electricity costs more than other heating fuels, notwithstanding the efficiencies of electrically-powered heating systems like heat pumps. Public sector organisations may therefore consider on-site electricity generation technologies. This should always be supported by an investable business case that does not expose the body to excessive risk. Public bodies could consider investing any savings made in energy costs into improvements to the fabric of their buildings and or the additional costs of clean heating systems

- The move to a circular economy approach to procurement by:

- thinking early about whether, what, how much and how to buy

- extending the life of equipment wherever possible

- considering leasing and shared ownership models where practical and economical

- reusing and repurposing equipment wherever possible

- where a purchase is required, procuring products that have been used (including refurbished products) or remanufactured, or are designed to be repaired, reused, refurbished, remanufactured or recycled.

This chapter lays out the high level actions that bodies should take, such as setting targets and developing a carbon management plan or equivalent. Detailed guidance on the individual measures that bodies could take, for example to decarbonise the heating in their buildings or to develop a sustainable travel strategy, will be provided in the topic supplements which will accompany this guidance.

5.2 Reducing emissions: background and context

5.2.1 The importance of taking action to reduce emissions

In order to limit future climate change caused by human activity, we need to rapidly reduce, by significant amounts, levels of greenhouse gases being emitted to the atmosphere. The most recent synthesis (AR6) from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) notes that we need to achieve 43% global emissions reductions from 2018-19 levels by 2030 to give a 50% chance of avoiding exceeding 1.5°C of global warming, the temperature targeted by the Paris Agreement in 2015 as the safe limit of climate change.

A more recent synthesis of the science suggests that five climate tipping points cross a 50% probability threshold, i.e. become more likely than not, at 1.5°C [23]. These include the collapse of the Greenland Ice Sheet, the abrupt thaw of boreal permafrost (which holds vast reserves of methane gas), and the die-off of low latitude coral reefs.

A climate tipping point by its nature is irreversible, representing a shift from one stable state to another. Once the process starts, even if we were to immediately cease all carbon emissions, change will continue until the end of its change process, shifting to a different stable state, e.g. the Greenland ice sheet would continue melting until gone. Whilst some of these tipping points may take hundreds or thousands of years to complete, they could be triggered in the coming decade if we do not achieve 1.5°C aligned decarbonisation pathways.

There is also a risk of cascading tipping points, where the triggering of one may raise temperatures sufficiently to trigger another. For example, the loss of Antarctic sea ice reduces the albedo effect, meaning the dark ocean surface absorbs more heat than the reflective white surface of sea ice, further warming the Earth. The abrupt thaw of the boreal permafrost would release vast reserves of methane gas, a potent greenhouse gas, further accelerating climate change and risking triggering further tipping points.

This highlights that every increment of warming matters, and stabilising the climate with minimal 'overshoot' beyond 1.5°C remains a key objective from a global and national equity viewpoint.

5.2.2 Maximising co-benefits and minimising unintended consequences

Co-benefits

Many of the actions to reduce emissions can deliver benefits for other policy areas such as health and wellbeing, equity and economic development. Bringing these benefits to the fore can help drive more ambitious climate action and provide an additional narrative across stakeholders. The Lancet Pathways to a healthy net-zero future noted:

"a focus on the opportunities for transformative change to an economy that supports health and equity within planetary boundaries can provide hope and a compelling vision of an inclusive and sustainable future, engage more diverse audiences and build support for change"[24]

There is increasing evidence that many actions to reduce emissions can deliver near-term health co-benefits[25]. Several programmes of work are underway in the UK and internationally to understand the scale of these benefits and how we can maximise them. Health co-benefits can be achieved when climate action addresses the building blocks of good health, for example through:

- promotion of active and sustainable transport which can increase physical activity, reduce air and noise pollution, and increase footfall in local areas with positive impacts on the local economy

- replacing fossil fuels with clean renewable energy which reduces air pollution

- consumption of sustainable and healthy diets

- promotion of accessible greenspace with benefits for mental and physical health.

Key to a just and equitable transition will be to ensure that benefits delivered by climate mitigation in relation to emissions, health, equity and social outcomes are fully accessible to all.

Unintended consequences

Implementation of mitigation actions can have both positive and negative, planned and unintended impacts on other policy areas and inequalities. For example, urban planting, both a mitigation and adaptation measure, can have benefits for health and wellbeing thereby supporting just transition outcomes. However, there is some evidence urban trees can increase property values and if unevenly distributed to lead to gentrification, making land inaccessible to low income residents [26], [27]. Similarly, retrofit schemes to increase energy efficiency are associated with improved health and social outcomes. However, increasing the airtightness of buildings without sufficient ventilation can contribute to poor indoor air quality. For some residents the cost of housing retrofit can be passed on in increased rental values, particularly for low income residents in the private rental sector. Where mitigation actions are not considered in relation to adaptation this can contribute to policy fragmentation and increase the risk of unintended consequences.

Whilst trade-offs across policy areas may be necessary, if the unintended impact on different population groups and different policy areas are not explicitly considered, these trade-offs can be unacceptable.

Working with stakeholders across policy areas, staff and the wider community, in particular the most affected population, using systems approaches to co-design and implement mitigation actions, and integrating mitigation and adaptation, can help support the delivery of multiple policy objectives, avoid maladaptation, reduce the risk of unintended consequences and prevent increased inequalities.

5.2.3 The net zero approach to mitigation

Activities that help reduce greenhouse gas emissions are referred to as climate change mitigation.

Climate mitigation is often framed by one of two concepts, net zero carbon or carbon neutral. These terms are sometimes used interchangeably. It is important that public bodies understand that they are not synonymous and actually reflect quite different approaches.

- Net zero carbon (or net zero) is intended to describe an approach which reduces an actor’s emissions as far as possible, with only the remaining unavoidable residual emissions offset through a credible and robust offsetting mechanism.

- Carbon neutrality by comparison can be achieved either in the same way as net zero carbon or by not reducing emissions whatsoever and offsetting 100% of them.

If a body achieves net zero carbon, it is by definition carbon neutral. However, carbon neutrality can be achieved without reaching net zero carbon.

Carbon neutrality is a less robust approach to climate change mitigation, and as such is not supported or aligned to the Scottish Government's approach to climate change mitigation. Public bodies should achieve climate mitigation through a net zero approach in a meaningful way.

In the net zero context, ‘unavoidable residual emissions’ are those emissions which remain after a body has taken all reasonable steps to reduce or remove them. They may include emissions related to specific processes or technologies for which no viable alternative currently exists, for example anaesthetic gases used in healthcare settings or refrigerant gases used in heat pumps.

Some sectors, such as aviation and maritime transport, face greater challenges and technological solutions may not currently be available on the market. In these cases, emissions should be reduced as far as possible, for example by seeking greater efficiencies and using alternatives where feasible. New technologies and solutions are continually being developed, and bodies should ensure that opportunities to further reduce or remove emissions are maximised when they become available.

Cost and complexity should not be used as excuses to delay mitigation action, particularly for situations where existing and robust alternative technologies are available. There may be a point beyond which costs become excessive, e.g. to remove the final residual 5-10% of emissions associated with a particular source. However, bodies should bear in mind the future costs that will be imposed on society should mitigation targets fail to be reached. Whole life analysis, incorporating the financial cost of carbon into business cases and appropriate use of impact assessments, as noted in section 4.5 above, can assist bodies to make robust and equitable decisions.

5.2.4 Decarbonisation pathways

It is important to understand that within the net zero carbon approach it is not simply the date by which an organisation reaches net zero that matters, but the pathway to net zero carbon as the following example demonstrates.

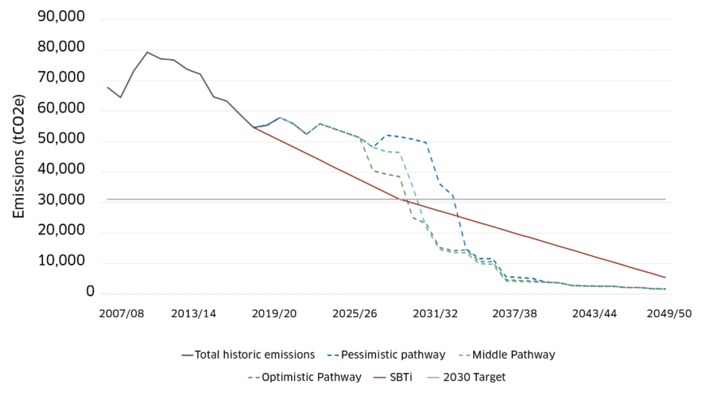

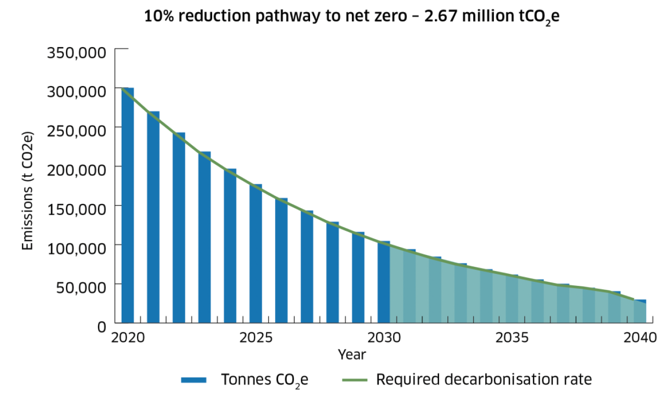

Example

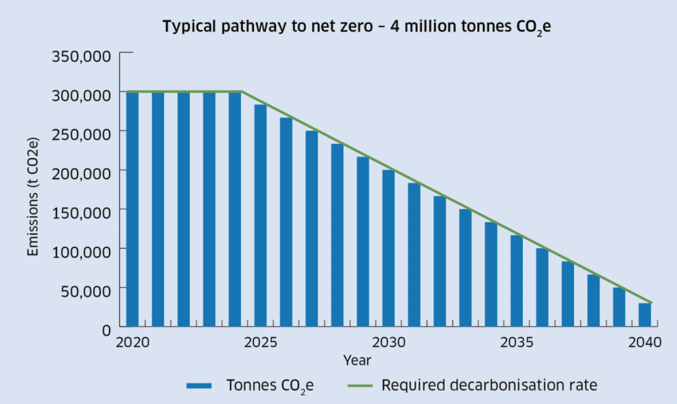

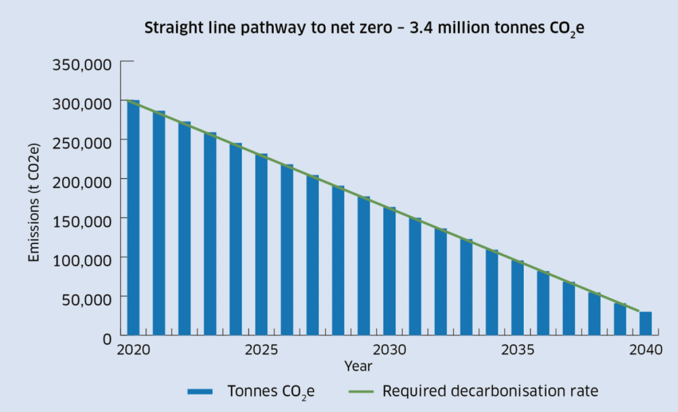

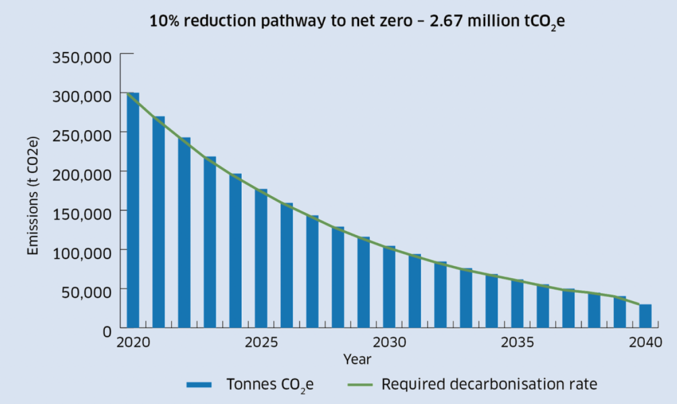

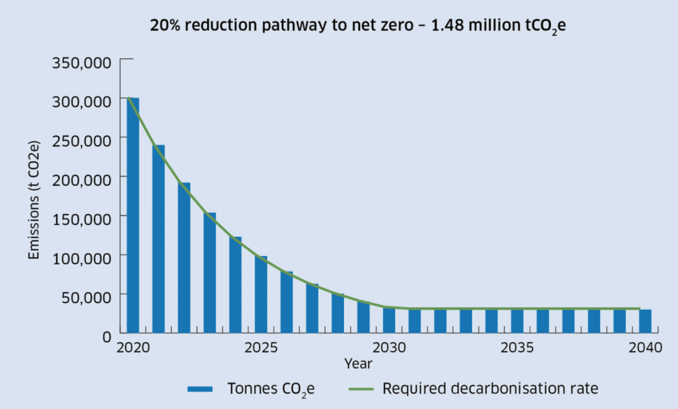

The figures below illustrate four different hypothetical decarbonisation pathways, each with the same starting and finishing points. Whether emissions are cut earlier or later in a decarbonisation pathway en route to a net zero carbon target has a material impact on the cumulative greenhouse gases emitted. As illustrated, an organisation might for example emit 4 million tonnes of CO2e (figure 4), or less than 1.5 million tonnes of CO2e (figure 7) depending on its approach, and still technically achieve net zero carbon by the same target date.

Figures 4 to 7: Hypothetical pathways to net zero illustrating cumulative carbon emissions based on early versus late carbon emissions reductions

Figure 4: Graph illustrating a ‘typical’ pathway to net zero emissions

Figure 5: Graph illustrating a ‘straight line’ pathway to net zero emissions

Figure 6: Graph illustrating a 10% reduction pathway to net zero emissions

Figure 7: Graph illustrating a 20% reduction pathway to net zero emissions

Due to the impact of cumulative emissions, public bodies should, wherever possible, set a corporate decarbonisation pathway that reflects the national pathway, and are strongly encouraged to set a pathway aligned to the IPCC recommendations for a 1.5°C, Paris Agreement pathway. Scotland's national emissions reduction target is net zero by 2045.

A pathway can be developed based on annual or less frequent targets; or bodies can take a carbon budgeting approach similar to the national approach. In either case, the absolute amount of carbon emitted over the given time or budget period (e.g. 1 or 5 years) decreases over subsequent periods, down to the target date and residual or zero emissions level.

The decarbonisation pathway should be calculated, visualised and planned for against scope 1 and 2 emissions combined, and separately for wider scope 3 (indirect) emissions. This is aligned to the Greenhouse Gas Accounting protocol. Should progress in scope 3 emissions reductions be ahead of target, this cannot be used to justify or "net off" any shortfalls in scope 1 and 2 emissions, they must be treated separately.

Public bodies can use nature based carbon removal insetting projects and offsetting to achieve net zero by counterbalancing residual unavoidable emissions within scopes 1 and 2. Bodies are not expected to use any purchased offsets against residual emissions within scope 3. Instead, they can achieve net zero emissions within scope 3 by ensuring the supply chain uses insetting or offsetting for those residual emissions owned by the supply chain. Any offsetting required by public bodies of the supply chain should meet minimum offset standards as defined in section 5.4.6 below.

Visualising a 1.5°C aligned decarbonisation pathway

In the visualisation below (figure 8), the red line represents the decarbonisation pathway required to give a 50% chance of limiting global warming to 1.5°C for a hypothetical organisation. The other lines represent alternative potential decarbonisation pathways for the organisation. Note that none of the proposed pathways in this figure satisfy a science aligned 1.5°C pathway due to the absolute amount of carbon emissions before 2030 being above the 1.5°C pathway ('overshoot'). For any emissions that overshoot the pathway, a later equivalent 'undershoot' is required to balance the total carbon emitted.

Figure 8: Graph illustrating a 1.5°C aligned decarbonisation pathway

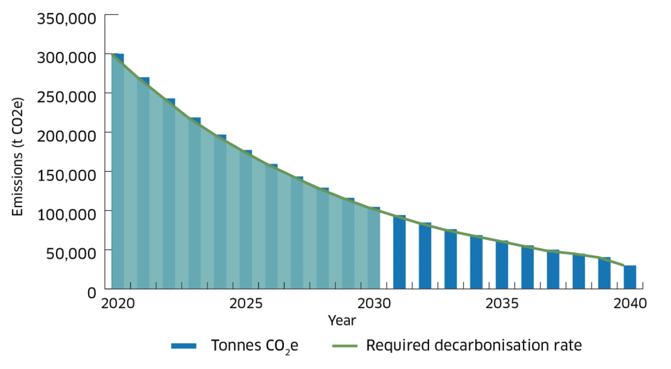

5.2.5 Carbon budgets

One way of monitoring the balance of carbon emissions ahead of target reductions is for public bodies to work to carbon budgets. As best practice, organisations taking this approach should work to at least two carbon budgets: one up to 2030, and one for the period 2031 to 2045. The reason for breaking the approach into two sections is due to the risk of triggering climate tipping points by exceeding 1.5°C, which is likely to happen on current projections without significant change before 2030. Splitting the time into four 5-yearly carbon budgets (2026 to 2030, 2031 to 2035, 2036 to 2040 and 2041 to 2045) would align with the national budget periods.

Figure 9: Visualising your carbon budget 2020 to 2030

Using one of the graphs from the example above to illustrate, the shaded area in the graph represents the carbon budget from 2020 to 2030.

Figure 10: Carbon budget 2031 to 2045

The carbon budget from 2031 to 2045, represented by the shaded area in figure 10 above, is significantly smaller than the carbon budget from 2020 to 2030. This is aligned to the idea that significant decarbonisation will have taken place before 2030. This leaves a much smaller carbon budget to work within, and with likely harder actions required to achieve these smaller reductions, having achieved the easier measures before 2030.

5.3 Reducing emissions in practice: key principles

To achieve the national net zero target of 2045, a step change in ambition and action is required.

Before outlining some principles that will help guide this step change in ambition, it is important to recognise that the approach bodies will take to developing their plans will differ due to their size, nature and purpose. This guidance is organised by duty (mitigation, adaptation and acting in the most sustainable way) for clarity. However, bodies should consider the duties together in an integrated way and may choose to develop plans or strategies that include all aspects.

To help focus action in those areas likely to have the greatest emission reduction impact, following a number of broad principles will be helpful.

Materiality

It will be necessary to focus efforts on those actions which achieve the most material impacts first.

Traditionally totemic actions may have been the focus of much climate action, such as recycling, electric vehicles or on-roof solar PV, which while they bring benefit are rarely the most impactful actions. In the future, there may be a greater focus on procurement policy and purchasing behaviour across the organisation's buying community, exploring major renewables installations with direct wire connections or sleeved power purchase agreements with explicit additionality in the contract.

It is worth noting that a significant proportion of Scotland's GHG emissions come from the land and land management activities. It is important that landholding bodies work to understand and address GHG emissions from their land, such as from degraded peatland, to maximise nature based opportunities to reduce emissions and to capture and store carbon, and to ensure that their lands are resilient in the face of the changing climate.

Wider influence

Closely related to materiality, is ensuring consideration of an organisation's wider impacts. For example, a local authority may achieve far greater emission reductions via adjusting the local plan by introducing a carbon tax per tonne of embodied and operational carbon on all new developments than by installing PV on the roofs of its own buildings (noting that the former will contribute to area wide targets that may in place, and the latter primarily to corporate targets).

Similarly, ensuring the local transport plan drives the reductions in car mileage aligned to Scottish Government targets for reducing car mileage may be more effective than converting its own fleet to electric vehicles. Ultimately both direct and indirect area wide emissions will need tackled, but prioritising those areas of influence with the largest impact will be critical to achieving a science aligned pathway.

Below are some prompts to help public bodies consider where their own potential wider impacts and influences on climate change might be. These can then be used as a starting point to explore action to be taken in response. For example, answering 'yes' to any of the questions should prompt further inquiry into the nature and materiality of the impact and the means by which this is best understood and managed.

Does your public body influence:

- the construction or reconstruction of any infrastructure?

- the construction methods and energy standards of homes, offices or other developments?

- energy generation, energy efficiency or energy consumption?

- planning and or land use strategies including development, farming, forest planting, forest management, nature based solutions or soil management?

- agricultural practices and production?

- travel patterns including number and length of journeys and the mode of travel?

- individual behaviour such as dietary choice, physical activity levels, or time in nature?

- waste arising or the amount of biodegradable waste going to landfill?

Urgency

Due to the risk of triggering climate tipping points, and the fact climate change is driven by absolute and cumulative carbon emissions, the importance of the pathway to the net zero carbon target is equally important to arriving at net zero on the target date.

Spending effort on actions that result in immediate reductions is important, whilst working on actions for the largest carbon reductions that might take longer to put in place. For example, replacing a large combined heat and power (CHP) plant with an air source heat pump might take over four years from concept to finish. Switching off that CHP (assuming there are back-up gas boilers) now would immediately offer significant carbon savings based on the difference between the emissions from the CHP and grid electricity emissions. This may result in increased revenue spend as electricity is more expensive than gas, but may be a rapid way to make significant carbon reductions whilst larger changes are worked on.

Public bodies should focus on urgent action to reduce emissions as far as possible as fast as possible over the next decade to minimise cumulative emissions, whilst still ensuring the goal of achieving net zero by 2045.

Supply chain

Most effort has, historically, gone into addressing scope 1 and 2 emissions, primarily generated by heating and powering buildings and fleet. For most public bodies indirect scope 3 emissions from the wider supply chain will make up the majority of emissions, and can be influenced or controlled by the public body to some degree. Categories of scope 3 emissions likely to be significant hotspots for public bodies include the emissions associated with purchased goods, works and services, capital assets and investments.

For example, whilst the scope 3 emissions from the construction of a new building are the scope 1 and 2 emissions of the construction company procured to undertake the project, ultimately the public body's decision to commission that building creates those emissions. An alternative, particularly in a hybrid working environment, of better utilising existing space via hot desk policies, refurbishment, repurposing buildings, or purchasing and refurbishing existing buildings rather than building new, would significantly reduce scope 3 emissions in this example.

Bodies wield considerable influence over their supply chain through their procurement practices and activities; influence that can cascade down through the tiers of a contract or supply chain. Climate and sustainability action can be built into the procurement process, from the initial identification of need and specification, through to the end of contact or the useful life of the asset.

Mainstreaming

Ultimately, in regards to each of the principles above, it is crucial that climate change action is mainstreamed in all public bodies' business processes and functions, as laid out in section 4.4 above. To do this effectively, public bodies will need to set targets and milestones and integrate climate change into business practice, through their existing processes and procedures. Embedding decarbonisation into core day to day business will be essential to achieve corporate and national net zero and other targets.

Demand management

When considering any source of emissions, whether energy or purchased goods, demand management is key – the lowest carbon option is always not to buy or consume at all. It is therefore important that approaches begin from a demand reduction perspective. This will be of particular importance as buildings and fleet are electrified, placing higher demands on grid infrastructure. Bodies should work to ensure that such demands are minimised, for example by reducing heat demand by insulating buildings and by undertaking behaviour change programmes with staff and building users.

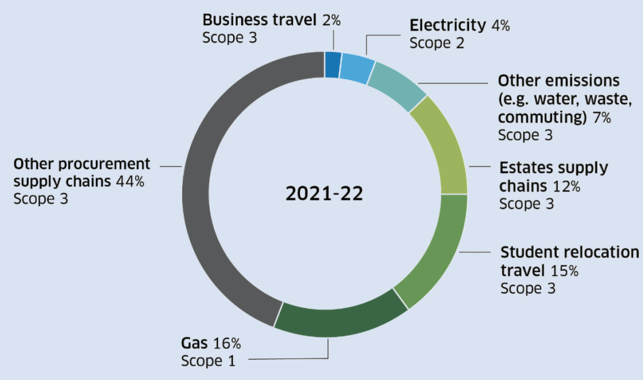

Worked example: Materiality

Taking a large Higher Education institution as an example, there are several areas of materiality in each of the main themes below.

Direct and indirect emissions

Indirect scope 3 emissions will make up a significant proportion of emissions, with most institutions having between 65% and 85% of their emissions within scope 3. Within scope 3, the material sources of emissions are typically, in order of size: the things the organisation buys including, in this example, laboratory equipment, IT equipment, vehicles and furniture; then international student flights; followed by the construction of new buildings, as illustrated in figure 11.

Within scopes 1 and 2, building heating will be the largest source of emissions, with electricity usage typically the next material source of emissions. Fleet emissions will usually be relatively small.

In this example the priority actions would be in engaging with procurement and the buying community to reduce purchasing wherever possible.

Figure 11: Illustrative large Higher Education emissions breakdown

Wider influence

In this Higher Education institution example, arguably the largest impact is through the education of its students, and through research into solutions such as renewable technology and energy storage. Whilst this does not directly impact on the Higher Education institution’s emissions, embedding climate change meaningfully across degree programmes, and incentivising and supporting research into climate solutions, is arguably the largest impact that the institution can have, whilst reducing its own direct and indirect measurable emissions.

5.4 Taking corporate mitigation action

This section outlines the key actions that all public bodies are expected to take, in a proportionate manner, to reduce their corporate (organisational) emissions. Many public bodies will already be at a more mature stage, and have some or all of these elements already in place.

- Climate change statement - a clear statement that outlines the body’s approach to climate change and sustainability. For example, many local authorities will have a high level statement that recognises the climate and nature emergencies, and makes a commitment to reach net zero.

- Climate change strategy – a strategy that outlines the body’s headline mitigation targets, key milestones and actions.

- Route maps – alongside the strategy, the body should develop route maps laying out, at a high level, steps illustrating how targets and milestones will be achieved. It may be appropriate for bodies to develop separate route maps for different areas of activity, e.g. for building and fleet decarbonisation.

- Targets – alongside an overarching net zero target, public bodies should set individual targets, such as a date for achieving clean heating in all of their buildings, and a date for electrifying their fleet. Targets should be ambitious but achievable, evidence-based, and appropriate to the body.

- Carbon management plans – carbon management plans are more detailed than the strategy, and lay out how the strategy will be implemented over a given time period. Smaller bodies may find that the strategy and plan can be combined as a single document, to take a proportionate approach.

- Action plans – action plans sit below the carbon management plan and lay out in detail interim steps that need to be taken. They should include critical milestones, decisions, dependencies, costs, key people and lead times.

- Monitoring and reporting – bodies should monitor progress and report on this through their corporate reporting processes.

5.4.1 Climate change statement

It is essential that public bodies have a statement or policy in place that clearly states their approach to climate change and sustainability. For example, many local authorities have a climate statement which recognises the interlinked climate and nature emergencies and makes a commitment to reaching net zero. Bodies should ensure that their statement and or policies cover all three climate change duties and are signed off at senior level.

Bodies should ensure that other pertinent policies, for example those relating to procurement and business travel, properly reflect the climate change duties. In particular the third duty, to act in the most sustainable way, is highly likely to be relevant to most other corporate policies.

All policies should be easily available to staff and stakeholders. As best practice bodies should make them publicly available, for example through their website.

5.4.2 Climate change strategy

Climate change statements can be a useful starting point when it comes to developing a climate change strategy. While actions on mitigation, adaption and acting sustainably have, for clarity, been laid out in separate chapters in this guidance, bodies may find that developing a strategy which encompasses all three areas is the most effective approach.

When developing or reviewing their climate strategy, public bodies should be cognizant of the wider policy context. For example, local authorities will have developed Local Heat and Energy Efficiency Strategies (LHEES) and Heat Network Zones (HNZs) which are likely to influence their corporate climate strategy and related plans, and certainly their area wide planning.

A climate change mitigation strategy should include:

- scopes 1 and 2, and detail the elements of scope 3 included

- a description of the wider material influences the organisation has on carbon emissions

- what the final decarbonisation targets are for the organisation, including any targets or action regarding its wider influence

- a visual breakdown of the organisation's carbon footprint

- a high level timeline of key actions that will achieve the targets (i.e. a route map, see section 5.4.3 below)

- a narrative of where the material impacts are, including an explanation of why certain actions are being prioritised over others chronologically or by effort

- the approach that will be taken to offsetting, which residual emissions offsetting will cover, and what proportion these residual emissions represent of the baseline carbon footprint

- a high level overview of risks.

As a minimum, and as detailed in Reporting chapter 8, bodies are recommended to include within their boundary scope 3 emissions from water, waste and waste water, business travel, student travel where relevant, and staff commuting and homeworking.

In addition to the above, the strategy should consider, where relevant, the contribution the body can make to wider net zero aims. For example, a body may generate significant waste heat which could be made available to other bodies or to a local district heat network. There will be other strategic opportunities to assist the wider public sector or community, and such opportunities should be maximised.

5.4.2.1 Sectoral approaches

Sector wide approaches to mitigation, including sectoral targets and aligned approaches, are being taken by key parts of the public sector. Due to the varied nature of public bodies, appropriate approaches and actions will differ.

NHS Scotland

A policy for NHS Scotland on the climate emergency and sustainable development (DL (2021) 38) was issued by Scottish Government to Health Boards on 10 November 2021. It sets out the aims and associated targets relating to sustainable development and climate change for Health Boards to work towards. It takes account of relevant wider Scottish Government policies and existing statutory duties. Further details will be provided in the Health and Wellbeing supplement in due course.

The NHS Scotland Climate Emergency Strategy 2022-2026 sets out actions directed at achieving the aims and targets in policy DL (2021) 38 noted above. It sets out actions which will either begin between 2022 and 2026, be completed during that period, or are already underway and will continue during that time.

Integration Joint Boards (IJBs)

While developing a climate change strategy is likely to be appropriate for most bodies, a different approach may suit others. For example, Integration Joint Boards (IJBs) are a unique type of public body and own no assets – their emissions and influence lie entirely in scope 3 indirect emissions. For IJBs, a more suitable approach would be to embed climate and sustainability action within their Strategic Plan.

Local authorities

Local authorities (LAs) have worked in partnership with central government to establish the Scottish Climate Intelligence Service (SCIS). This jointly funded service aims to build capacity within councils to develop and deliver area wide programmes of emission reductions. The SCIS supports a national digital platform to collate area wide emissions data, enabling LAs to build a baseline of emissions and calculate, visualise and report on their area wide emission reduction strategies. The service will, through a network of regional officers, support LAs in building the knowledge and skills to use the data effectively to enable planning, monitoring, reporting and delivery of area wide climate action.

A consistent approach by local authorities to developing climate change plans, covering both corporate and area wide emissions, will be facilitated by the use of a standard template (see Annex B).

Further and Higher Education

The Scottish Funding Council's (SFC) Net Zero and Sustainability Framework for Action establishes a clear, long-term plan to support Scotland's colleges and universities through the transition to net zero, reflecting improved corporate accountability and collective responsibility across the Further and Higher Education sectors.

The SFC expects institutions to have or to put in place organisation-wide net zero plans by the end of 2024, and to be able to highlight key priorities and dates for delivery of these.

5.4.3 Route maps

Net zero carbon targets are typically longer term targets ranging from 5 to 25 years into the future. Science aligned decarbonisation pathways require significant carbon emission reductions well before typical net zero target dates. In addition, where woodland creation is a key part of achieving a net zero target, the time lag between planting and active sequestration (typically 15 to 25 years) means that such activities also require urgent action if aligning to net zero 2045 targets.

A route map is therefore helpful in breaking down the journey to net zero, helping to ensure that sufficient action is taken to deliver the chosen pathway.

Route maps can take a variety of visual forms. A high level visual giving key dates and top line actions can be useful for overview presentations.

A more detailed quantification of carbon emissions reductions delivered by each intervention can be useful in delivering a granular analysis of how the decarbonisation pathway is going to be achieved, and to clearly identify any gaps between planned action and the pathway.

High level route maps can include actions on both scopes 1, 2 and 3, as well as insetting and offsetting, as a helpful overview of the full mitigation programme, and if not over-crowded could also include adaptation.

A public body route map will typically include the following specific actions on decarbonisation as a minimum:

- heat in buildings

- fleet

- business travel

- waste

- reduction in electricity consumption (excluding increases caused by the electrification of heating and the transition to electric vehicles).

As best practice, bodies should also include:

- supply chain action

- insetting and offsetting action, where relevant

- land and land use, where relevant

- investments.

Table 2 below is an example of the kind of high level actions that might be used to populate a decarbonisation route map for a public body.

Year |

Decarbonising heat |

Decarbonising fleet |

Electricity |

Supply chain |

Investments |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

2025 |

All end-of-lease vehicles to be replaced by EV |

Achieve 50% LED lighting across the estate |

Circular economy policy; buy less, share, lease etc. Publish supply chain route map |

||

2026 |

Deep retrofit of most carbon intensive buildings |

Introduce cargo bikes for appropriate journeys |

Upgrade most carbon intensive equipment |

Analyse supply chain impacts |

|

2027 |

Deep retrofit of less carbon intensive buildings |

Complete upgrades of onsite charging infrastructure |

Achieve 75% LED lighting across the estate |

Begin supplier engagement to reduce largest emissions |

|

2028 |

First major CHP replaced |

100% of car and LCV fleet replaced by EV |

33% supply chain emissions 1.5°C aligned |

Divest from all fossil fuels |

|

2029 |

Retrofit of least carbon intensive buildings |

Achieve 100% LED lighting across the estate |

Establish 1.5°C pathway for investments |

||

2030 |

Second major CHP replaced |

25% of HGV fleet to be low emissions vehicles |

25% of electricity consumed to be self-generated using renewable technologies |

66% supply chain emissions 1.5°C aligned |

Start adjustment of investments to ensure 1.5°C alignment |

2031 |

|||||

2032 |

District Heating Network for social housing completed |

50% of HGV fleet to be low emissions vehicles |

33% of electricity consumed to be self-generated using renewable technologies |

80% supply chain emissions 1.5°C aligned |

Complete adjustment of investments to ensure 1.5°C alignment |

*Note: the examples provided in the table above are illustrative only. It is for each public body themselves to determine the most appropriate range of actions and measures in their journey to net zero.

Route maps should typically cover at least a five year period (e.g. to align with the body's carbon management plan), and could cover the full journey to net zero carbon if appropriate, and where actions and timelines are understood (i.e. to illustrate the full strategy). It is likely that most public bodies will have a clearer picture of the next five years, with decreasing certainty with time. For that reason public bodies in most cases should develop route maps 5 to 10 years in duration, noting any material action that will be required beyond the end of the route map horizon, and noting that this will be updated at least one year in advance of the end of the current route map timeline.

It is likely, especially for larger public bodies, that achieving net zero will be reliant to some extent on the activities of others, such as for the development of heat networks. Bodies intending to electrify the heat in their buildings and fleet may be dependent on upgrades to grid infrastructure taking place in advance of work commencing on their sites. A vital part of developing the route map will therefore be identifying the key partners and stakeholders associated with each element or project, establishing contact and building relationships. This process can be lengthy, and bodies are encouraged to establish these relationships early, especially with their Distribution Network Operator (DNO) in relation to grid upgrades, as these can take many months or even years to come to fruition.

5.4.4 Emissions reduction targets

The approach to setting targets

Targets often form the most visible and public part of an organisation's strategy for taking climate action. It is therefore important that these are well considered, evidence-based and appropriate to the body. When setting targets, bodies should consider the nature and functions of their organisation, their resources and the actions that will be needed to deliver on the targets, as outlined in the following sections.

It can be helpful to approach target setting using the SMART criteria:

- Specific – be clear on what is included and excluded in your target or targets, and avoid general 'catch-all' targets. For example, if setting a target related to car kilometres travelled per year, be clear as to whether that applies to pool cars, hire cars, grey fleet, etc. Aim to develop specific targets relating to the body's significant sources of emissions, such as heat in buildings or road fleet.

- Measurable – to enable realistic targets to be set, and for performance to be monitored and reported on, the target must be measurable. Consider the data sources available, data quality, where improvements can be made to enhance accuracy and reliability of data, and to streamline or automate data collection and verification processes.

- Ambitious (but achievable) – it is important that targets are stretching and drive action, but it is also important that they are evidence-based and are felt, with due effort, to be achievable. Unachievable targets may, in effect, set a body up to fail and may work against delivery by facilitating delays and the prioritisation of other work or spend, and by demotivating staff. There are also significant reputational risks associated with missing targets, or with having to alter them in the future.

- Relevant – targets should be relevant to the organisation and to the body's overall footprint. Efforts should be focused where they will have the most impact, or where targets support other priority outcomes or policies.

- Timebound – effective targets should be timebound. They should include a target date plus, where relevant, a baseline year which progress is measured against. Where a target lies in the more distant future, such as 2045, consider milestones and how to maintain focus and help ensure that progress stays on track.

Corporate emission reduction targets

Corporate emission reduction targets should include, as best practice and where relevant:

- an overall net zero target for scopes 1 and 2 of no later than 2045, earlier where possible

- individual targets for zero direct emissions from heating of buildings, zero direct emissions from road fleet vehicles (some public bodies may find it appropriate to have separate targets for cars, LCVs and HGVs) and zero direct emissions from the ferry fleet

- targets related to land use and land use change, in particular where land based emissions, such as those from degraded peatland, are a source of direct scope 1 emissions

- targets covering other direct emissions, e.g. from use of machinery

- targets covering waste, e.g. waste to landfill, recycling rates, circular economy

- targets related to procurement

- targets related to other sources of indirect emissions, such as business travel, car kilometres travelled, etc.

The organisational net zero strategy should map out any intended use of nature-based carbon removals on the body's landholdings (insetting) or carbon offsetting required to achieve net zero targets. The residual unavoidable emissions that will be sequestered should be estimated as part of net zero planning. Residual emissions should be as small as possible, and any assumptions and uncertainties clearly explained. Further information is provided in section 5.4.6 below.

In addition to net zero targets and those related to decarbonisation of buildings and fleet, bodies are strongly encouraged to set wider additional targets that reflect, or go further than, national policy, such as a 20% reduction in car kilometres by 2030.

In all cases, targets should include:

- specific information around what is, or is not, covered by the target

- a target date

- where relevant, baseline information.

For example, a target focused on reducing car kilometres travelled could be:

- 20% reduction in car km taken for business travel by 2030, including pool cars and grey fleet, in relation to the baseline year 2019.

Targets may relate to carbon (e.g. absolute or relative reductions in emissions) or may take alternative forms, as in the car kilometres example above. For example, a body may decide that the most effective way for them to tackle the emissions associated with procurement would be to carry out an emissions reduction programme based on prioritisation of procurement of goods, works and services with a high climate impact. Public bodies may use early market engagement and the contract management process to identify key performance indicators (KPIs) that can be used to seek and measure improvements against a baseline during the lifetime of the contract. KPIs should be relevant and proportionate to the contract in question. This may start with qualitative data, moving to quantitative date over time as data available improves.

Other measures of progress on procurement and climate maturity may include, for example, indicators from the Procurement and Commercial Improvement Programme (PCIP) such as numbers of staff having completed climate literacy training or evidence that climate has been consistently addressed in relevant procurements.

Illustrative baseline targets can be found in the template Carbon Management Plan (Annex A). This is aimed at smaller and less complex bodies and should be adapted to suit the circumstances of the individual body.

5.4.5 Carbon management plan

A carbon management plan (CMP) is a more detailed document than a climate change strategy, and lays out how the strategy will be implemented over a given time period. While the term CMP is used in this document, bodies may use different terms such as, for example, carbon reduction plan or climate action plan.

The CMP should include the boundary and governance arrangements, the baseline and targets set by the organisation and a visualisation of the decarbonisation pathway. It should reflect the principles outlined at the beginning of this section, i.e. an approach created through the lens of materiality, wider influence, supply chains, urgency and demand reduction, and which embeds approaches reflecting all of the above in the core business governance systems and processes.

Illustrative targets are included in the template baseline carbon management plan in Annex A.

An important element of developing the CMP will be the identification of key stakeholders and partner organisations, who will be critical to successful implementation of the plan. Such stakeholders may be internal or external and are likely to include the Distribution Network Operator (DNO), other public bodies, local Planners and district heat network developers or providers. Internal stakeholders are likely to include Finance, Estates, Fleet, Facilities Management and Procurement colleagues.

It is important that an organisation's CMP and other key strategies and plans are aligned with, where relevant, the estate strategy, planned maintenance and plant replacement schedules, fleet strategies and fleet replacement plans, and the procurement strategy. There are likely to be many dependencies between these strategies and plans, particularly in relation to budgets and implementation.

Public bodies may often achieve value-for-money by installing clean heating systems when existing plant has reached (or is nearing) the end of its useful or economic life and where works can be combined with wider building improvements. Public bodies should understand and refer to their planned maintenance schedules for heating system replacement and building refurbishment projects. When making a decision on the technology to install in place of the current heating system, public bodies should undertake feasibility studies and decisions should follow the process set out in the supplementary guidance on the Built Estate (to follow in due course).

Interim solutions

Expensive or technically complex interventions can take longer to develop or gain approval for, so that emissions reductions are not realised in the short or medium term. In such cases, public bodies could explore interim solutions that can mitigate emissions in the meantime whilst long term interventions are developed. It may be possible to utilise hybrid technology that helps reduce emissions until a full transition to a zero emissions system can be realised.

Leasing assets whilst awaiting capital budget, maturation of technology or approval for long term purchases is another bridging mechanism that allows for short term emissions reductions whilst working on long term solutions. For example, a body may have an asset at end of useful life. While a zero emissions alternative may not currently be available, the body may be confident that an option will be brought to the market within a few years. In this case, leasing a replacement asset as an interim stage could be an appropriate approach and avoid the lock-in that a purchase now would result in.

Flexible approaches

Approaching budgets flexibly may be necessary in reflecting short, medium and long term decarbonisation opportunities, and bodies are encouraged to consider their investment budgets holistically. It may be helpful to temporarily move budget from, for example, estates to fleet whilst estates plans are further developed but immediate spend is not required; and then move fleet budget to estates later when major capital works are required. Similar policy-related budget flexibility may be wise in maximising area wide impacts.

5.4.5.1 Template plans

Annex A contains a baseline carbon management plan template and associated guidance. It is intended to assist smaller public bodies that may have limited capacity. It has been designed to align with the mandatory public bodies climate change duties reporting. In all cases, public bodies should use the template as a starting point and develop it to reflect their own needs and circumstances.

Annex B contains a template climate change plan for local authorities. This is a more extensive document and covers mitigation, adaptation and acting sustainably from both an organisational and an area-based perspective. It is intended to act as a guide to what local authorities' plans are expected to include.

5.4.6 Dealing with residual emissions: carbon insetting and offsetting

Definitions of carbon offsets, carbon insets and carbon credits, including types of credits (emission reductions, removals and avoidance), as used in this guidance, are provided in the glossary.

The main focus of climate change mitigation action for Scottish public bodies should be action within Scotland to reduce greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions and increase nature-based carbon sinks. Public bodies should have plans and demonstrable actions in place to reduce GHG emissions to as close to zero as possible, including land-based GHG emissions. Offsetting and carbon removal insetting projects must not be a replacement for emission reductions.

Offsetting should only be used as a last resort and, in most cases, as an interim measure while solutions to emissions that bodies are currently unable to eliminate are developed. Offsetting and insetting should form part of organisational targets and transition plans aligned with Scotland's statutory national emission reduction targets and the global goals of the Paris Agreement.

The use of insetting and offsetting should be clearly laid out in the carbon management plan or equivalent, that is transparent as to:

- why and how insetting and offsetting are to be used as a tool on the route to net zero

- what proportion (%) and amount (tCO2e) of emissions are to be inset or offset

- what type of insets and offsets are to be used and where they are sourced from

- which emissions sources or categories these are to cover

- how the insets and offsets will be appropriately accounted for to avoid double-counting (e.g. in the case of peatland credits which may also be part of the body's land-based scope 1 emissions).

Where insetting and or offsetting have been deemed appropriate, public bodies with landholdings should maximise opportunities for nature-based insetting projects on their own land. On the route to organisational net zero carbon, investment in insetting projects should be prioritised ahead of the purchase of carbon offsets from elsewhere. Landowning public bodies should consider carefully the emissions saving claims they make in relation to nature-based projects on their land, in line with good-practice carbon accounting and reporting principles (further guidance will be provided in the Land and Nature supplement in due course). For example, peatland carbon credits produced on a public body's own landholding cannot be used to counterbalance other emissions within their inventory as this would constitute double counting (as land-based emissions from degraded peatland, where relevant, should be reported as part of the public body's land-based scope 1 emissions).

For some public bodies with larger landholdings, nature-based projects on their land may enable the removal and storage of more carbon than they emit through their operations, or that is required for insetting residual emissions as part of a Paris Agreement aligned transition plan. Public bodies with a nature-based carbon surplus beyond their own requirements to reach net zero should give careful consideration as to the most appropriate use for this surplus. Central government bodies could consider allocating (which could include selling or gifting) the surplus to other public bodies who are unable to reach net zero within their own boundary. Other bodies, including local authorities, should ensure that decisions made in relation to the end-use of such carbon savings or credits are transparent and equitable, and consistent with wider climate change duties.

Opportunities for insetting projects on a public body's landholdings should be balanced with other local, regional and national priorities including food security, housing and energy. Care should be taken to promote, and not to harm, other objectives especially climate adaptation and nature recovery. Where possible, nature-based projects on the public estate should be designed to achieve multiple objectives in line with other relevant SG policy, including the Land Use Strategy, the Natural Capital Market Framework and the Scottish National Adaptation Plan.

Consideration should be given to wider linked issues and policies. Partnership working, collaboration and area-based approaches will be important to achieve the highest quality outcomes, for example via landscape scale clusters of public and Scottish Crown Estate land. Projects should benefit local communities and contribute to a just transition. Guidance on delivering community benefits from land is published by the Scottish Land Commission.

Public bodies with coastal holdings should also consider the protection and restoration of blue carbon habitats such as saltmarsh and seagrass: blue carbon is the organic carbon captured and stored in marine and coastal habitats. With their ability to sequester and store carbon, to provide natural coastal protection, and to support complex biodiverse ecosystems, such habitats offer a small but important role in climate change mitigation, adaptation and resilience.

Adaptation and mitigation agendas should, where possible, be integrated, ensuring that climate risk assessments are included in carbon and GHG emissions assessments. Emissions from degraded or vulnerable nature-based carbon stores may affect the ability of public bodies, particularly those with larger landholdings, to reach net zero. Therefore targeted actions to restore any such degraded carbon stores, especially peatlands, may be required. Where these activities are also to be used for insetting purposes, care needs to be taken with the type of claims made linked to high-integrity carbon accounting and reporting practices as noted above.

When considering changes to land use on public land as part of insetting or offsetting activities, carbon leakage should be avoided, i.e. where actions taken on a public body's landholdings displace carbon-generating activities elsewhere which then take place outside the reporting boundary.

If offsetting activity is to be undertaken as part of an organisation's net zero transition plan, there is a strong preference for public money to benefit communities and high-integrity projects within Scotland, as opposed to investing in international offsets. Supporting high-integrity nature-based carbon reduction projects within Scotland can bring benefits to local economies and communities, enhance biodiversity and provide wider environmental benefits, in addition to contributing to progress towards Scotland's statutory national emissions reduction targets.

As laid out in the GHG Protocol Land Sector and Removals Guidance, public bodies should ensure that any carbon credits obtained for offsetting purposes meet quality criteria including additionality, credible baselines, permanence and avoid leakage. Credits should be high-integrity and verified under Scottish Government supported carbon codes such as the Peatland Code and the Woodland Carbon Code. Use of credits verified under the Codes can provide confidence that the GHG Protocol's quality criteria will be met: for example, both the current SG supported Carbon Codes include tests of legal and financial additionality.

Offsetting by public bodies should only be used as a last resort. Scotland's climate change legislation sets a default position that statutory national emissions reduction targets will be met solely through domestic effort, without any reliance on purchase of international offsetting credits by the Scottish Government. Any international offsets purchased by other bodies would not contribute to progress towards Scotland's national emissions reduction targets. However, there may be other motivations for bodies to engage in international offsetting. Scottish Government has adopted the principle of climate justice internationally and recognises that mitigation activity and carbon offsetting projects must not cause loss and damage to communities or habitats overseas.

5.4.6.1 Offsetting business travel emissions

Bodies may be asked, for example as part of funding conditions, to offset any business travel emissions associated with research or other programmes. As noted, the preference is for emissions generated in Scotland to be offset within Scotland. Where it is not possible to source high integrity, verified credits directly attributable to Scottish projects, a reasonable approach would be to purchase UK-based credits. Any purchased credits should be from a government supported code such as the Woodland Carbon and Peatland Codes. Bodies should refer to section 8.3.6 in relation to how purchased credits should be included in the annual public bodies climate change duties report.

Offsetting international flights

As noted above, bodies may find that a requirement to offset business travel, including international flights, is a condition of grant or research funding, in particular in the higher education sector. If a body chooses to offset international flights, whether business travel or other flights such as student travel, the country of departure should be taken as having national ownership of those emissions. For example, for a return flight from Scotland to the USA, the emissions from the outbound leg to the USA would be classed as Scottish emissions, and those from the return leg as USA emissions. Such Scottish emissions should be offset or inset within Scotland. The body may choose where to offset the non-domestic share, i.e. within Scotland or internationally.

Bodies who wish to offset the domestic share of international aviation emissions may do so using Peatland Code credits. Offsetting of such emissions is not, at the time of writing, permitted using Woodland Carbon Code credits due to differences in the way that the codes have been established. Bodies could also, where feasible, consider nature-based carbon removals projects on their own lands, externally verified to an MRV standard equivalent to one of the SG supported carbon codes.

They could also consider, for the non-domestic share, the purchase of high integrity, verified international credits from an accredited scheme such as the Gold Standard.

5.4.6.2 Selling carbon credits from projects on publicly owned land

Landowning public bodies may be in a position to generate investment in nature-based projects through the sale of carbon credits. Any such projects should be included in the body's carbon management, climate change or equivalent plans, and contribute to key outcomes that the public body has identified. Such outcomes are likely to go beyond carbon and could include adaptation, flood risk management and biodiversity. Any credits intended for sale should be high-integrity and verified through one of the government supported codes.

Bodies should consider carefully:

- whether the sale of credits is appropriate to their function, objectives and legal basis or constitution

- whether the nature-based project supported by carbon finance would be considered additional, corporately in terms of any potential legal drivers that influence the body's objectives or functions and therefore how it is required to manage its land (e.g. legal obligations to reduce land-based emissions) and also at the project level in relation to whether the project passes the additionality tests of the code in question

- their own organisational carbon footprint and how the sale of any carbon credits may impact on their ability to achieve their own net zero targets

- wider benefits and outcomes the investment can be used to help deliver

- what additional considerations may be required, for example, who the carbon credits are being sold to and for what purpose (e.g. that the credits are to be used for offsetting residual emissions only or as part of a transitional plan). Bodies should be careful to ensure that the intended use of the credits avoids any accusations of 'greenwashing' and potential reputational damage.

It is for individual bodies to make such decisions, taking their own legal advice where necessary.

Carbon credits verified through the Woodland Carbon and Peatland Codes can be used to offset emissions generated in the UK. However, there is a strong preference for credits arising from publicly-owned and Scottish Crown Estate land in Scotland to be used only to offset emissions generated within Scotland. Bodies should assure themselves that the buyer intends to use the credits against emissions generated by their operations within Scotland only.

The design of the arrangements for checking and auditing that only emissions from activity in Scotland are being offset by carbon credits issued from public land is for individual public bodies to determine. Bodies could, for example, take a risk-based approach such as requiring information and a statement of assurance from each buyer. This could be backed up by an audit process drawing on a sample-based approach as an alternative to the need to audit every purchaser. However, it would be a matter for individual bodies to ensure they comply with legal and financial duties and Scottish Public Finance Manual guidance. Further guidance on demand-side issues and engagement with buyers of nature-based credits, including carbon, is included in the Natural Capital Market Framework.

Responsible private investment for natural capital projects on the public estate has the potential to play an important role contributing to land use policy delivery and value for money in public expenditure. Public bodies considering private investment for natural capital projects should ensure that their projects and financing arrangements are aligned with relevant Scottish Government policy, notably the vision for high-integrity markets for natural capital as set out in the Principles for Responsible Investment in Natural Capital and the Natural Capital Market Framework. This includes ensuring that projects deliver integrated land use and community benefits, contributing to a just transition. The overall goal should be to ensure that any engagement by public bodies with private finance for natural capital is responsible and of high integrity.

5.4.7 Action plans

Below the CMP will sit an action plan, or series of action plans. These will take the headline actions outlined in the CMP, and clearly lay out the interim steps that need to be taken in order to achieve the end results. The action plans should include critical milestones, decisions, dependencies, costs, key people and lead times. They can form the basis of a project plan to deliver that element of the work.

For example, the CMP may include a target to replace any remaining fossil fuelled fleet vehicles with electric vehicles by 2030. The action plan would break this down into a series of steps, likely arranged by financial year, required to meet this target. Typical steps might include: getting senior management sign off for the target; confirming vehicle costs and lead times with suppliers; developing a 5-year budget; getting sign off on the budget; updating the fleet replacement plan; and developing a plan to schedule in the placing of orders, delivery of new vehicles, disposal of old vehicles, etc.

Developing action plans will be vital to ensure the CMP is delivered. Many projects will have dependencies, for example gaining Planning permission or being contingent upon electrical grid upgrades, and it is important that these are identified early and allowed for. They can assist in the identification and management of risks, and facilitate resource planning. Progress should be monitored and reported on through existing project management processes and KPIs.

5.4.8 Monitoring and reporting

Public bodies with statutory reporting duties under the Climate Change (Duties of Public Bodies: Reporting Requirements) (Scotland) Order 2015, as amended, must report all scope 1 and 2 emissions, along with relevant scope 3 emissions, as outlined in chapter 8 Reporting below.

Bodies out-with the mandatory reporting duty are encouraged to follow the guidance provided in the Reporting chapter, as best practice, and to include the information within their annual corporate reports. Climate action and sustainability should be integrated into existing monitoring and reporting processes and documents, such as the annual corporate report and organisational KPIs.

Public bodies should monitor and report emissions annually, tracking progress against their decarbonisation pathways and or carbon budgets. Detailing any emissions over or under budget, and tracking a cumulative figure, is key to staying within the organisation's carbon budget.

As well as reporting on overall progress toward targets, bodies should ensure that progress on action plans is monitored and reported on, to ensure that barriers and potential delays to delivery are identified early, and solutions can be developed.

5.5 Area wide emissions and wider influence

Section 44 of the 2009 Act provides that public bodies have duties, in exercising their functions, to address mitigation, adaptation and sustainability. Many public body functions are key to supporting wider society's transition to net zero, building climate resilience and achieving sustainable development outcomes. This section addresses the area wide emissions that public bodies have a critical role in tackling as part of Scotland's just transition net zero.

Public bodies, especially local authorities, can have significant influence on area wide emissions. This is recognised in a range of policy documents and reports emphasising the importance of local area action on climate change, notably:

- The Scottish Parliament's Net Zero, Energy and Transport Committee Report on the Role of Local Government and its Cross-Sector Partners in Financing and Delivering a Net Zero Scotland (January 2023)

- Environmental Standards Scotland's Climate Change Delivery Investigation Improvement Report (December 2023)

- The Climate Change Committee's Local Government and the Sixth Carbon Budget Report (2020)

- The Carbon Scenario Tool report by Edinburgh Climate Change Institute (May 2022)

5.5.1 Local area wide emissions and place based climate action

‘Area wide’ and ‘place based’ are terms often used interchangeably. Broadly speaking, for the purposes of this guidance, they are used as follows:

- Area wide refers to the totality of activities either planned or currently occurring within a defined geographic area. This aggregates and then breaks down measures, activities, and actions at an area wide scale, in this context those specifically related to sources of emissions and actions for emissions mitigation.

- Place based refers to the design of future solutions and approaches by considering the specific needs and attributes of a place (however that place is defined). This recognises the complex and interconnected nature of a place, and in this case the impact that has on both emissions from a place and the effectiveness of measures to target them. The Place Standard with a Climate Lens is a useful resource for addressing climate change at a place based level.

Places, and place based solutions, should be designed and optimised at different scales for different challenges and solutions. In this guidance, area wide is used primarily to describe plans for emissions reduction which target emissions sources at a local authority level.

5.5.2 What makes up area wide emissions

'Area wide emissions' refers to all emissions allocated to local authority areas. There are various methodologies that can be used for this, but protocols and data sets are being established that are improving consistency and clarity. Key for work in Scotland are:

- The Global Protocol on Community-Scale Emission Inventories, produced by the GHG Protocol initiative of the World Resources Institute (WRI) and the World Business Council for Sustainable Development (WBCSD).

- The Local Authority GHG Emissions datasets produced annually as Official Statistics by the UK Government, under the National Atmospheric Emissions Inventory (NAEI).

- The PAS 2080 Standard (and associated Guidance from the Institute of Civil Engineers) on the carbon assessment of infrastructure, buildings, and wider public sector investment decisions.

Estimates of greenhouse gas emissions are produced for each local authority and National Park area in the UK from the following broad source categories:

- industry (including electricity-related emissions)

- commercial (including electricity-related emissions)

- public sector (including electricity-related emissions)

- domestic (including electricity-related emissions)

- transport

- land use, land use change and forestry (LULUCF) (including removals of carbon dioxide from the atmosphere, so that net emissions from this sector can sometimes be negative)

- agriculture (including electricity-related emissions)

- waste management (distributed based on the waste arising in each local authority.

Figure 12: Territorial emission sources of a typical local authority area wide inventory

Emission sources typically included in the inventory:

- industrial – electricity, natural gas, large industrial installations and other

- domestic – electricity, natural gas and other

- transport – road (motorways, A roads and minor roads), diesel railways and other

- LULUCF net emissions – forest land, cropland, grassland, wetlands, settlements, harvested wood products and indirect nitrous oxide

- agriculture – electricity, natural gas, livestock, soils and other

- commercial - electricity, natural gas and other

- public sector - electricity, natural gas and other

- waste management – landfill and other.

Emission sources excluded from the inventory:

- supply chain emissions from goods and services that occur out-with Scotland

- aviation and international shipping.

Breaking down emissions by source enables the alignment of local area plans, actions and measures for emissions reduction and can be used to develop cost estimates for area-wide emissions reduction pathways. An example of this is the Net-Zero Carbon Roadmap for Edinburgh published in 2020.

Local area wide emissions reduction plans should also be designed to secure co-benefits relevant to the National Performance Framework and policy commitments on adaptation, wellbeing, health, economic development, justice and inclusion and biodiversity improvement.

The Scottish Climate Intelligence Service, established in 2023, supports a consistent approach to area wide emissions accounting and local area wide emission reduction planning and action across all local authority areas.

5.5.3 Public bodies duties and action on area wide emissions

5.5.3.1 Public bodies' influence and collaboration

Public bodies need to use their various functions to influence the reduction of area wide emissions. Central to this is the role of local authorities and their Community Planning Partners. Other public bodies can support plans, projects and policies at local authority level to support efforts to reduce emissions locally.

Key to working on area wide emissions is recognising that public bodies have significant influence on these emissions, while they mostly do not have direct control. Much like local economic development and public health improvement, for example, public bodies should work to use their various functions and to collaborate across the public sector and with communities, businesses and third sector organisations, to influence local area emissions from various sources.

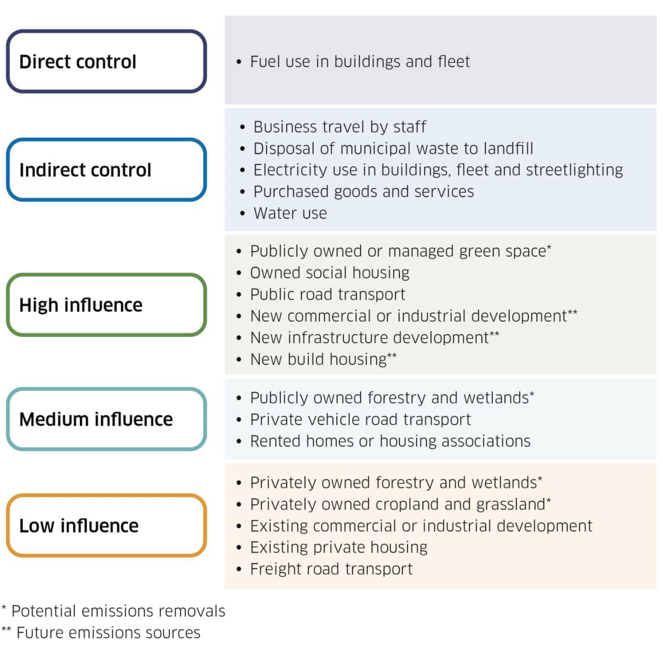

Figure 13: Control and influence on area wide emissions (developed from Figure 1 in the Carbon Scenario Pathfinder Project report (2022), ECCI [28])

5.5.3.2 Developing plans, projects and policies to reduce area wide emissions

Having clarified the area wide emissions inventory, public bodies (especially local authorities) should develop a plan for area wide emissions reduction. These plans need clarity on targets, emission reduction pathways, projects and policies. Local authorities and public bodies can draw on Scotland's Climate Change Plan for relevant policies and projects, and also supplement these with local initiatives.