Coronavirus (COVID-19): modelling the epidemic (issue no.115)

Latest findings in modelling the COVID-19 epidemic in Scotland, both in terms of the spread of the disease through the population (epidemiological modelling) and of the demands it will place on the system, for example in terms of health care requirement.

Coronavirus (Covid-19): modelling the epidemic in Scotland (Issue No. 115)

Background

This is a report on the Scottish Government modelling of the spread and level of Covid-19 in Scotland. This updates the previous publication on modelling of Covid-19 in Scotland published on 8th December 2022. The estimates in this document provide an overview of the situation regarding the virus and help the Scottish Government, the health service and the wider public sector plan ahead.

This is the final scheduled issue of this publication series.

Key Points

- The reproduction rate R in Scotland is currently estimated as being between 1.0 and 1.2 as at 6th December. Both the lower limit and the upper limit have increased since the last publication.

- The last time the lower limit for R was estimated to be at or above 1 was in issue 103 of this publication, in reference to 21st June 2022.

- The daily growth rate for Scotland is currently estimated as between 0% and 3% as at 6th December. Both the lower limit and the upper limit have increased since the last publication.

- The last time the lower limit for the growth rate was estimated to be 0% or higher was also in issue 103 of this publication, in reference to 21st June 2022.

- EMRG was unable to reach a consensus on the incidence of new daily infections in Scotland as at 6th December.

- The most recent wave of the Scottish Contact Survey (8th – 14th December) indicate an average of 6.2 contacts. This has increased by 11% compared to the previous wave of the survey (24th - 30th November) where average contacts were 5.6. Prior to the Covid-19 pandemic, the average daily contacts for adults in the UK were reported to be 10.8.

- Mean contacts in the work setting have increased by 58% compared to the previous wave of the survey, whereas mean contacts in the home and other setting (contacts outside home, school and work) have decreased by 7% and 22% respectively.

- Mean contacts in the 40-49 age group have remained at a similar level compared to the previous wave. Mean contacts have increased in all other age groups by at least 7%.

- The largest increase in interactions between age groups compared to the previous wave of the survey was between the 18-29 age group with themselves .

- Pubs and restaurants had the largest increase in percentage of participants visiting compared to the previous wave of the survey, increasing from 54% to 60%. The percentage of participants attending an outside event saw the largest decrease, reducing from 72% to 69%.

- The percentage of people wearing a face covering where they have at least one contact outside of the home has increased from 19% to 20% since the last wave of the survey.

- The percentage of people who had taken at least one lateral flow test in the previous 7 days increased from 18% to 21% since the last wave of the survey.

- The SPI-M-O consensus view is that by 31st January 2023, daily hospitalisations from Covid-19 in Scotland are estimated to be between 9 and 228, and hospital occupancy is estimated to be between 581 and 2055.

- Nationwide, during the period 1st – 14th December, wastewater Covid-19 levels were in the range of 43 to 74 million gene copies per person per day (Mgc/p/d), an increase relative to the previous two weeks of data (33 – 48 Mgc/p/d during 17th – 30th November). This indicates a continued increase in wastewater Covid-19 levels over five consecutive weeks from low levels previously seen in November.

Overview of Scottish Government Modelling

Modelling outputs are provided here on the current epidemic in Scotland as a whole, based on a range of methods. Because it takes a little over three weeks on average for a person who catches SARS-CoV-2 (the causative agent of Covid-19) to show symptoms, become sick and either die or recover, there is a time lag in what our model can tell us about any changes in the epidemic.

The Scottish Government presents its modelling outputs to the Epidemiology Modelling Review Group (EMRG). These outputs are included (shown in green) in Figure 1. Outputs from other modellers are shown in either cyan (for models based only on cases data) or purple (for models based on other data). The consensus range is the rightmost (in red).

The R value, growth rates and daily incidence are also estimated by several independent modelling groups based in universities and the UKHSA. Estimates are considered, discussed and combined at the EMRG, which sits within UKHSA. These are based on data up to 19th December.

The consensus view of the EMRG across these methods was that the value of R in Scotland is between 1.0 and 1.2 as of 6th December 2022 (Figure 1). The lower limit and the upper limit have both increased since the last publication. R is an indicator that lags by two to three weeks.

Source: EMRG

The consensus from EMRG is that the growth rate in Scotland is between 0% and 3% per day as at 6th December. The lower limit and the upper limit have both increased since the last publication.

EMRG was unable to reach a consensus view on the incidence of new daily infections in Scotland as of 6th December.

What we know about how people's contact patterns have changed

Scottish Contact Survey contact matrices are published as open data. The dataset contains mean contacts between age groups for all waves of the survey since its inception in August 2020 up to the final wave on 8th – 14th December.

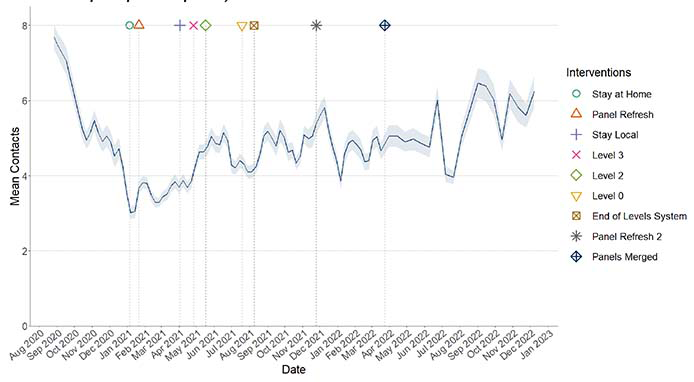

This final wave of the Scottish Contact Survey (8th – 14th December) indicates an average of 6.2 contacts. This has increased by 11% compared to the previous wave of the survey (24th November - 30th November) where average contacts were 5.6, as seen in Figure 2.

Prior to the Covid-19 pandemic, the average daily contacts for adults in the UK were reported to be 10.8 from the UK-wide POLYMOD study[1].

Mean contacts in the work setting have increased by 58% compared to the previous wave of the survey, whereas mean contacts in the home and other setting (contacts outside home, school and work) have decreased by 7% and 22% respectively.

Figure 3 shows how contacts change across age group and setting. Mean contacts in the 40-49 age group have remained at a similar level compared to the previous wave. Mean contacts have increased in all other age groups by at least 7%.

The heatmaps in Figure 4 show the mean overall contacts between age groups for the surveys relating to 24th - 30th November and 8th - 14th December and the difference between these periods. The largest increase in interactions between age groups compared to the previous wave of the survey was between the 18-29 age group with themselves.

Pubs and restaurants had the largest increase in percentage of participants visiting compared to the previous wave of the survey, increasing from 54% to 60%. The percentage of participants attending an outside event saw the largest decrease, reducing from 72% to 69%. See Figure 5.

Figure 6 shows the percentage of people wearing a face covering where they have at least one contact outside of the home. This has increased from 19% to 20% since the last wave of the survey .

Figure 7 shows the percentage of people who have taken at least one lateral flow test in the previous 7 days. This has increased from 18% to 21% since the last wave of the survey.

What the modelling tells us about projections of hospitalisations and hospital occupancy in the medium term

SPI-M-O produces projections of the epidemic (Figure 8 and Figure 9), combining estimates from several independent models. These projections are not forecasts or predictions. They represent a scenario in which the trajectory of the epidemic continues to follow the trends that were seen in recent data and do not include the effects of any future policy or behavioural changes. The delay between infection, developing symptoms and the need for hospital care means they cannot fully reflect the impact of behaviour changes in the two to three weeks prior to 19th December. The projections include the potential impact of vaccinations over the next few weeks. Modelling groups have used their expert judgement and evidence from UKHSA, Scottish Universities & Public Health Scotland, and other published efficacy studies when making assumptions about vaccine effectiveness.

Figure 9 shows the SPI-M-O consensus on hospital occupancy. Hospital occupancy is determined by the combination of admissions and length of stay, the latter of which is difficult to model with confidence.

The SPI-M-O consensus view is that by 31st January 2023, daily hospitalisations from Covid-19 in Scotland are estimated to be between 9 and 228, and hospital occupancy is estimated to be between 581 and 2055.

What can analysis of wastewater samples tell us about local outbreaks of Covid-19 infection?

Levels of Covid-19 RNA in wastewater (WW) collected at a number of sites around Scotland are adjusted for population and local changes in intake flow rate (or ammonia levels where flow is not available). See Technical Annex in Issue 34 of Scottish Government Research Findings for the methodology. These reports are based on the most recent data available.

Nationwide, during the period 1st – 14th December, wastewater Covid-19 levels were in the range of 43 to 74 million gene copies per person per day (Mgc/p/d), an increase relative to the previous two weeks of data (33 – 48 Mgc/p/d during 17th – 30th November). This indicates a continued increase in wastewater Covid-19 levels over five consecutive weeks from low levels previously seen in November.

In Figure 10 the wastewater estimates are superimposed on the ONS Coronavirus Infection Survey (CIS) estimates of Covid-19 prevalence. The case rates obtained from this survey continued to be relatively low, with little variation from the start of November up until the most recent results on 5th December.

The increase in WW Covid-19 levels is mostly driven by the Central Belt of Scotland, which encompasses major cities such as Glasgow and Edinburgh. See Table 1 of the Technical Annex.

Looking to the future

What may happen in the future around SARS-CoV-2 is uncertain and therefore there are a number of possible Covid-19 futures that may occur in the future. For example, the current Omicron wave may dissipate leaving low levels of Covid-19, or a new variant may emerge potentially having vaccine escape or increased severity, or people's behaviours may change. One approach to this uncertainty is to model alternative versions of the future through the development of different Covid-19 scenarios.

Given what we know about Covid-19 these possible futures range from a world where immunity reduces Covid-19 hospitalisations and ICU to low levels, through to variant world where a variant with immune escape enters Scotland and Covid-19 hospitalisations and ICU could increase. In between these two extremes there could be possible futures where people's behaviour becomes polarised between those who continue with Covid-19 precautions e.g. hand washing etc. and those who do not.

The scenarios we provide in the next section look at what could happen for planning purposes, not to forecast what will happen. The assumptions are based on our most up to date knowledge, but do not include the effect of future changes in treatment of Covid-19 e.g. widespread use of antivirals or changes in behaviour in response to high levels of infections e.g. in variant world. Therefore, in the most extreme scenarios the peak may be lower than suggested if behaviour or restrictions changed.

There is no linear progression between the worlds and all are plausible. Each world inherently contains a different threat level requiring a different approach to management.

Immune World

In this possible future vaccines and natural immunity are effective at keeping Covid-19 at low levels. New variants may emerge in Scotland but for the foreseeable future infections are based around Omicron.

Infections may decrease from current levels over the coming weeks and months to very low levels. Likewise hospital and ICU occupancy may follow this trend relieving the pressure on healthcare services. Issues with new variants are not considered in this world and therefore levels of infections remain low (see Figure 11).

In Immune world Covid-19 in Scotland reduces below epidemic levels, becoming endemic. Cases of Covid-19 therefore spring up only as rare outbreaks which are controlled through public health measures. People's lives return to something close to normality e.g. physical distancing is not needed but people still choose to self-isolate and hygiene is good. As vaccines are effective, take-up of first/second/third doses are good and boosters become part of an annual cycle like flu. The numbers of people who need medical treatment or hospitalisation for Covid-19 remain low.

The focus moves away from Covid-19 response and into recovery. This includes addressing learning losses, treating Long Covid and working through the hospital backlog. Wellbeing measures improve with reduced anxiety and increased happiness. Those from the highest risk groups feel they can reintegrate without government interventions. The economy continues to recover from the effects of Covid-19. Travellers do not face significant issues with trips overseas.

Polarised world

In this world, vaccines and natural immunity are effective at reducing infections. The approach followed relies on individual risk assessment and behaviours. However, society becomes polarised as some continue to take up vaccines and follow guidance while others are more reluctant. Covid-19 becomes a disease associated with those who do not or cannot get full vaccine benefit and do not or cannot adopt a risk based approach.

Impacts on hospital/ICU occupancy are uncertain but levels may be higher than what may happen in Immune world (see Figure 12).

Cases of Covid-19 spring up and are hard to control in those who are not vaccinated or vulnerable. People's lives return to a "new normal" but, due to polarised groups in society with some following and some not following guidance, infections remain.

Vaccines are effective so older and more vulnerable people come forward for future doses in high numbers.

The focus remains on Covid-19 and the shift onto recovery is slower. Existing learning losses are harder to rectify and continue to accrue due to infections within education settings. The hospital backlog is difficult to address as hospitals are still dealing with Covid-19 cases. The population becomes polarised in to those whose wellbeing improves e.g. lower risk people and those whose wellbeing deteriorates e.g. higher risk or poorer people whose levels of anxiety increase as Covid-19 circulates. They continue to experience greater illness, greater poverty or disruption to their income. The economy continues to be impacted from the effects of Covid-19.

Variant world – vaccine escape with same severity as Delta

In this possible future a variant with vaccine escape emerges in Scotland presenting a challenge even for fully vaccinated people. This new variant leads to increased transmission, but not to increased severity compared to previous variants. In this scenario other NPIs may need to be put in place for a short time. This world is similar to what has happened in Scotland with the emergence of Omicron.

Omicron may be reduced to low levels within Scotland as a new variant takes over. This causes a new wave of Covid-19 infections as well as increases in hospital and ICU occupancy. People's lives are disrupted due to the increasingly high levels of infections leading to time off work ill or isolating.

To show the potential impact assume a new variant appears in Scotland following the return to work/school after mixing across the festive period. The timing is uncertain and a potential new variant may appear sooner than this or significantly later but has currently been lined up following the festive period to show illustratively what could happen. The new variant may cause Omicron infections to decrease significantly or disappear entirely (and is not shown). The new variant is modelled with similar transmissibility and vaccine escape as Omicron with severity characteristics similar to Delta. It could lead to high levels of infections leading to hospital occupancy rising above capacity restrictions. With sustained high levels of infection we could again see increased staff absences in a number of sectors that were affected by this in the recent Omicron wave (see Figure 13).

The focus remains on Covid-19 and it is hard to shift on to recovery. Continued infections within education settings and staff shortages may impact schools. The Covid-19 strain on hospitals is high due to the very high numbers of infections and workforce pressures grow making it difficult to address the hospital backlog. Wellbeing measures deteriorate with people reporting low happiness and general 'tiredness with it all'. The economy continues to be impacted from the effects of Covid-19 with many people off work. Travellers may not want to come to the UK as the new variant sweeps through.

Variant world – vaccine escape with increased severity compared to Delta

As with the other example of Variant world, a new variant appears in Scotland following the return to work/school after mixing across the festive period. The timing is uncertain and a potential new variant may appear sooner than this or significantly later but has currently been lined up following the festive period to show illustratively what could happen.

The new variant may cause Omicron infections to decrease significantly or disappear entirely (and this is not shown on the graph). It is modelled with similar transmissibility and vaccine escape as Omicron with severity characteristics 50% higher than Delta, purely for illustrative purposes.

It could lead to high levels of infections leading to hospital occupancy rising significantly. With sustained high levels of infection we could again see increased staff absences in a number of sectors that were affected by this in the recent Omicron wave (see Figure 14).

The focus remains on Covid-19 and it is hard to shift on to recovery. Continued infections within education settings and staff shortages may impact schools. The Covid-19 strain on hospitals is high due to the very high numbers of infections and workforce pressures grow making it difficult to address the hospital backlog. Wellbeing measures deteriorate with people reporting low happiness and general 'tiredness with it all'. The economy continues to be impacted from the effects of Covid-19 with many people off work. Travellers may not want to come to the UK as the new variant sweeps through.

What next?

This issue will be the last scheduled publication of Coronavirus (Covid-19): Modelling The Epidemic In Scotland.

It was announced on 9th December that this week's UKHSA publication of the R value and growth rates will be the final one. As a consequence of this decision, the Scottish Government will also stop publishing these values after this week.

Additionally, the Scottish Contact Survey has now closed. The research panel started in August 2020 in order to inform epidemiological modelling to estimate metrics such as the R number and growth rates. As a result of the decision to stop publishing these metrics from this week, the intended purpose no longer remains and the Scottish Government will no longer collect this data. Consequently the 8th – 14th wave reported on in this issue will be the final wave of the survey.

Covid-19 incidence data will continue to be accessible from the Office of National Statistics' Covid-19 Infection Survey bulletins and both UKHSA and Scottish Government will continue to monitor the state of the pandemic.

The archive of models can be accessed through the Data Science Scotland GitHub organisation. See the Technical Annex of issue 96 for further details.

Contact

There is a problem

Thanks for your feedback