Deaths in Prison Custody in Scotland 2012-2022

This report analyses and presents an overview of data published by the Scottish Prison Service on deaths in prison custody in Scotland.

4. Scottish Prison Population - Overview and Trends

The National Statistics on Scotland’s prison population show that the level and composition of the Scottish prison population has changed over time. Prior to the Covid pandemic, Scotland’s prison population had been rising. While the average daily prison population declined between 2011-12 and 2017-18, by late 2018 it was rising rapidly. The average daily prison population peaked at approximately 8,200 in 2019-20. Over the same period, while the number of people spending time in prison each year had been considerably higher than the population on any given day, the number fell substantially – falling by around 16% from 20,535 in 2011-12 to 17,311 in 2019-20 (Figure 1).

The Covid pandemic had considerable impacts on the prison population. While there has been a longer term downward trend in the numbers of individuals experiencing imprisonment year-on-year, the number of individuals that spent any time in prison in 2020-21 and 2021-22 was considerably below pre-pandemic levels (14,241 and 14,441 respectively).

This decrease likely reflects the impacts of justice system responses to public health measures over the period. Justice system responses to public health measures in 2020-21 led to: a decreased volume of custody cases reported to the Crown Office and Procurator Fiscal Service, and an increased volume of undertakings reports; a reduced likelihood of an accused being remanded; a reduced volume of concluded cases in courts, with subsequent reduction in custodial sentences issued and growth in the trial backlog. In addition, early release was granted for 348 eligible short term sentenced prisoners in the initial stages of the pandemic under provisions in the Coronavirus (Scotland) Act 2020.

Combined, these changes across the justice system impacted both the in-flows to custody and the out-flows from custody throughout 2020-21 and 2021-22. As a result, the average daily prison population in both years was considerably below the immediate pre-pandemic period at approximately 7,300 and 7,500 respectively.

The difference between the number of individuals that experience imprisonment compared to the average daily prison population in any one year, demonstrates that there is considerable churn in the prison population. Whilst some individuals are serving long sentences, many enter and leave custody after a short period of time. Some individuals enter and leave custody multiple times in any given period.

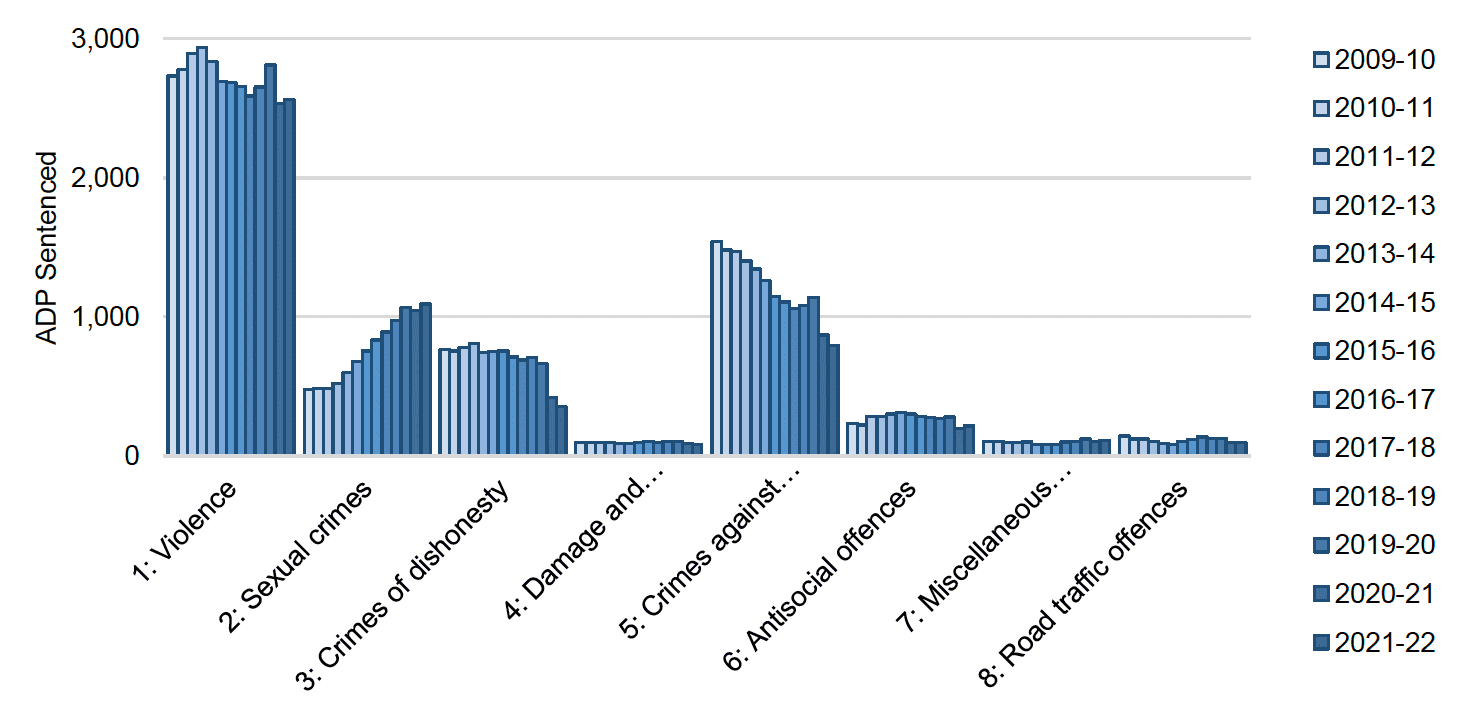

The composition of the prison population has also changed over time. Over the decade to 2019-20, the sentenced prison population became increasingly comprised of individuals convicted of violent and sexual offences, and those serving longer sentences. As shown in Figure 2, those with an index offence of serious violence were the single largest group in the sentenced average daily population in 2019-20, accounting for just over a third of the total. The average daily population serving sentences for rape and attempted rape (offences that attract long custodial sentences) trebled between 2009-10 and 2019-20, and the overall long term prison population grew substantially.

As illustrated in Figure 3 below, there has been continued growth in the average daily population serving indeterminate sentences (life sentences and Orders of Lifelong Restriction) and rapid rises in those serving longer determinate sentences (4+ years) from 2017-18 to 2019-20. These patterns became more pronounced over the pandemic period as the short term sentenced prison population fell considerably. Since 2020 the remand population has grown substantially, shifting the balance between the sentenced and remand populations. In 2021-22, around 25% of the average daily population was held on remand – compared to around 19% in 2019-20.

The age profile of the prison population has also changed. The longer term reduction in individuals spending time in custody each year has been driven almost entirely by a reduction in young people and younger adults (those under 30 years), with the average daily population of those aged under 21 years falling considerably from just over 800 in 2011-12 to just under 190 in 2021-22. At the same time, the average daily population aged 35+ years has increased steadily.

In line with these patterns, the average age of individuals experiencing imprisonment is increasing. The average age of prisoners has increased from 31.8 years in 2010-11 to 36.9 years in 2021-22, and the proportion of prisoners aged 55 or over has more than doubled in the last decade rising from 3.5% to 8.1%.

The prison population remains overwhelmingly comprised of men. In 2011-12, women comprised just 5.8% of the total prison population. The impacts of the pandemic described above were proportionately greater in the women’s prison population. As such, by 2021-22 the proportion of women in the prison population had fallen to 3.8%.

A further consistency over time is that the prison population is disproportionately comprised of individuals from areas of multiple deprivation. The Scottish Index of Multiple Deprivation (SIMD) is the Scottish Government's standard approach to identifying areas of multiple deprivation in Scotland[3]. It is a relative measure of deprivation across 6,976 small areas (data zones). The SIMD ranks areas in Scotland in terms of their relative deprivation. Deprivation is considered in relation to seven domains: income, employment, education, health, access to services, crime and housing. The most deprived 20% of areas are found in quintile 1 or deciles 1 and 2. The least deprived 20% of areas are found in quintile 5 or deciles 9 and 10.

In 2012-13, almost 53% of arrivals to custody were from areas in quintile 1 (deciles 1 and 2), the most deprived 20% of areas in Scotland. In 2021-22, this figure was almost 48%. Living in an area of deprivation is linked to poorer health outcomes, higher drug use and increased mortality rates[4][5].

It should be noted however that SIMD is an area-based measure of relative deprivation therefore not every person from areas ranked as ‘most deprived’ by the SIMD will themselves be experiencing high levels of deprivation or the outcomes associated with living in those areas. Nevertheless, a recent (2022) assessment of Scotland’s prison population[6] found high levels of health and social care needs and of co-morbidity (i.e. individuals having more than one mental health, physical, social care or substance use related need). The final assessment synthesis report also identified a series of challenges to addressing the needs of the prison population through existing health and social care arrangements.

Contact

Email: DiPCAG@gov.scot

There is a problem

Thanks for your feedback