The Disability Assistance (Scottish Adult Disability Living Allowance) Regulations 2025: islands communities impact assessment

This island communities impact assessment (ICIA) considers the potential impact of the Disability Assistance (Scottish Adult Disability Living Allowance) Regulations 2025 on Scottish island communities.

5. Key Findings

This section provides an overview of issues for Scottish rural/remote and island communities that are relevant for these regulations. Island stakeholders have emphasised the importance of understanding the island experience. Each island has its own specific considerations and constraints. Rural Scotland accounts for 98% of the land mass of Scotland and 17% of the population.[11]

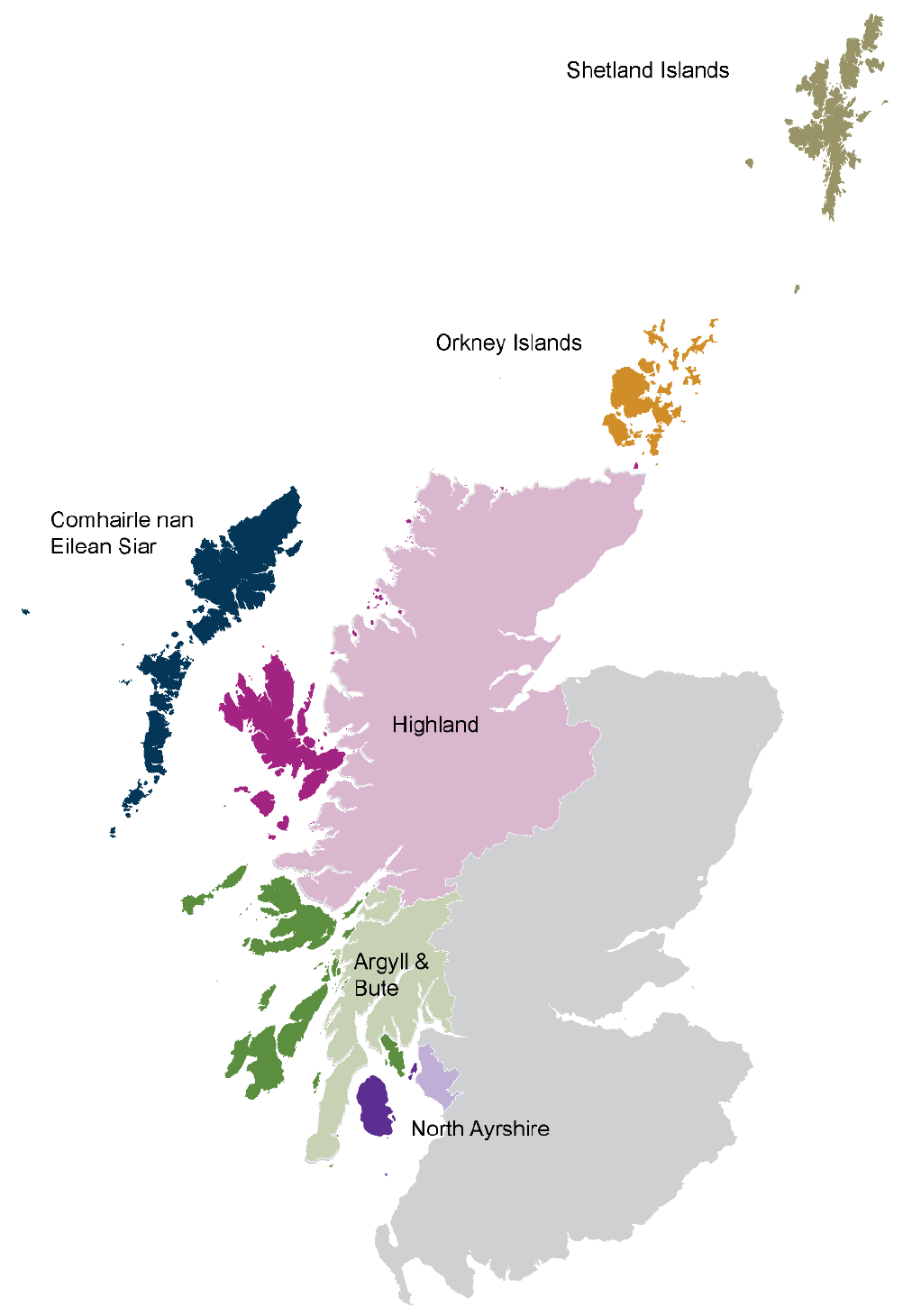

At the time of the 2011 Census, Scotland had 93 inhabited islands with a total population of 103,700 (which was 2% of Scotland’s population).[12] Of these islands, only five are connected to the Scottish mainland by bridge or causeway. The Islands Act identifies six local authorities representing island communities in Part 4 of the Act (Section 20 (2)), which are Argyll and Bute Council; Comhairle nan Eilean Siar/Western Isles; Highland Council; North Ayrshire Council; Orkney Islands Council; and Shetland Islands Council. Amongst them, Orkney, Shetland and Western Isles are entirely island authorities, while Highland, Argyll and Bute and North Ayrshire local authorities cover island regions as well as mainland regions.

5.1 Demography and Health

According to the 2011 Census, 83% of island residents reported their health as being ‘Very good’ or ‘Good’ compared with 82% for Scotland as a whole. The proportion of island residents with a long-term (lasting 12 months or more) health problem or disability that limited their day-to-day activities was just under 20%, including 9% who reported their daily activities were limited a lot. The corresponding proportions for Scotland as a whole were very similar.[14]

62% of island residents are aged between 16-65 with the median age being 45 which is higher than the average across Scotland as a whole.[15] Rural Scotland has higher proportions of people aged 65 and over in the local population (averaging 23.5%) compared to the rest of Scotland (18%).[16]

1 in 8 people aged over 65 in Scotland experience poverty in the last year of their life. The impact of social inequalities on health outcomes in older people is well documented.[17] [18]

Based on information from the Department for Work and Pensions’ Stat-Xplore service, analysts believe around 1.4% of adults with entitlement to Disability Living Allowance in Scotland live in island communities as of May 2023. This accounts for approximately 1,184 people.

In Scotland, as with the rest of the United Kingdom, disabled people experience higher prevalence of poverty, food insecurity, material deprivation and lower mental wellbeing than the general population.[19] In Scotland, the poverty rate after housing costs for people in households with a disabled person was 24% (560,000 people each year). This compares with 18% (550,000 people) in a household without disabled household members.[20] Data related to disability specifically in island communities is not available.

The effects of the COVID-19 pandemic are believed to have worsened pre-existing inequalities between different groups and communities. It has had a significant and disproportionate impact on certain groups, including disabled people, households in poverty, and older people, the latter of which make up a more significant proportion of rural populations.[21] While people in remote rural areas were four times less likely to die from COVID-19 that people in urban areas, the acceleration of digitisation and automation risk worsening the long-term mental health impacts of digital exclusion and social isolation.[22]

5.2 Cost of Living

The cost of many amenities and activities are higher for people living in island communities than those living on the mainland. A lack of choice and accessibility means that shopping, mobile phone services and broadband can be more expensive for people living in island communities compared to those on the mainland. The greater distances between amenities and remoteness means that day to day travel, postage, fuel, day-trips and holidays are also more expensive for people in remote communities.

A 2015 report published by Citizens Advice Scotland identified several issues that particularly impact consumers in rural areas. These include the cost and availability of essential goods and services including transport, utilities, housing and shopping.[23]

Further, a 2016 report published by Highlands and Islands Enterprise states that households in remote rural areas of Scotland experience costs that are 10-40% higher than elsewhere in the United Kingdom. Furthermore, households in the most remote parts of Scotland can experience additional costs that are even greater than 40%, and a food basket of typical essential items was found to cost as much as 50% more on island communities than elsewhere in Scotland.[24]

Research published by the Scottish Government in 2021 built upon previous reports and also concluded that households in remote rural areas of Scotland typically add 15-30% to their household budgets when compared to urban areas of the United Kingdom. Although this study did not include additional costs associated with fuel, it found evidence of additional costs in a variety of spending categories, with the dominant extra cost coming from the cost of travel.[25]

The Joseph Rowntree Foundation reported that levels of poverty among disabled people are generally underestimated. Because disabled people’s needs are often greater than for those without a disability, the cost of living for disabled people is frequently higher. These costs are higher in island and remote communities due to an environment that is less accessible, with higher costs for reasonable adjustments to technology, housing and transport.[26]

The Trussell Trust reported that disabled people are disproportionately affected by food insecurity and are consequently overrepresented in referrals to food banks, which is partly driven by cost of living. They add that disabled people face significant additional financial burdens beyond typical day-to-day living costs due to managing their health conditions through adaptations and therapies not provided by the NHS or local authorities. Some disabled people also have health conditions or use medication that require specialist diets which come with additional associated costs.[27]

While Scottish Adult Disability Living Allowance is not intended to be an income replacement benefit, it is intended to provide support with helping to meet the extra costs associated with having a disability, such as paying for care and mobility needs. For some disabled people, it will bring additional entitlement to other benefits via passported benefits, tax credits and other forms of assistance.

5.3 Connectivity and Accessibility

Citizens Advice Scotland have identified issues of grid, utilities, digital and travel as key barriers for people in accessible rural, remote rural and remote small towns.[28]

Alongside the areas identified by Citizens Advice Scotland, research briefings from 2017 for the Islands (Scotland) Bill [29] indicates that residents of islands rely on ferry crossings and air travel to reach the mainland and larger islands to access key services such as secondary and higher education, care, and medical services.

In 2011, the proportion of island households with at least one car or van available was 79%, compared with just over two-thirds (69%) nationally.[30] Remote rural households are far more dependent on cars compared to households in urban areas due to limited availability of alternatives, and often need to make further journeys to access amenities.[31]

In rural remote areas and island communities, disabled people face a lack of access to opportunities that are more readily and frequently available to those on the mainland or in urban areas. Furthermore, a lack of accessibility to employment, education and leisure opportunities can be made more difficult for someone with a physical condition, especially when transport options are limited.

Bus services in remote and island communities can be unreliable and are often community run. Even where buses are available, they often run rarely and timetables do not always meet the needs of people living in the community. Not all islands are served by buses and there are not always taxis available. It is known that disabled people on islands rely heavily on neighbours, friends and families driving them as a primary means of transport. Furthermore, if there is already someone with a wheelchair or pram on the bus it is not always possible for a wheelchair user to board.

The needs of wheelchair users or others with mobility issues, can be different in island and rural communities than the needs of wheelchair users in an urban environment due to more challenging terrain and weather. An absence of good quality internet connection can significantly impact on an individual’s ability to socialise, partake in cultural activities and access support services, particularly where people already have difficulty taking part in activities as a result of a disability or health condition.

Rural and island communities often experience poor connectivity, and the accelerated trend towards automation and digitisation during the COVID-19 pandemic has further exacerbated risks associated with digital exclusion.[32] Social Security Scotland will offer a multi-channel approach, including telephone, webchat, paper-based and face-to-face support (including home visits to clients where necessary) to ensure that people are not isolated through a lack of access to technology.

Social Security Scotland local delivery officers will share locations with other services so that they are based where clients currently go to ensure that clients can access advice and support in existing island locations. Social Security Scotland will also support individuals to gather supporting information. This includes, if authorised by the individual, gathering supporting information on their behalf if they do not have this to hand. For individuals living in rural or island communities, this may be of particular benefit as it may be difficult for residents to gather supporting information from a professional given the remoteness and lack of connectivity.

5.4 Culture

Stakeholders have previously identified cultural barriers to applying for other disability benefits delivered by the Scottish Government, and while Scottish Adult Disability Living Allowance is a closed benefit with no new applications it is reasonable to believe similar barriers may exist for individuals in receipt of Scottish Adult Disability Living Allowance too. These barriers were attributed to the nature of island communities; and while some research indicates that there are also positive benefits of close-knit communities, like providing support to vulnerable neighbours,[33] the need for individual privacy remains important.

Dignity, fairness and respect underpins how Social Security Scotland will deliver Scottish Adult Disability Living Allowance, including protecting the privacy of individuals. For instance, Social Security Scotland’s Local Delivery team will share locations with other services so that they are based where individuals currently go to ensure that they can access advice and support in existing island locations.

Because Scottish Adult Disability Living Allowance is a closed benefit with no new applications there will be a very targeted distribution of stakeholder resources within local communities. Social Security Scotland proactively translates information resources about the benefits it delivers into Gaelic, as well as many other languages, which may be culturally relevant and beneficial to some island communities.

5.5 Choice and Representation

We know that many island and remote communities have limited options with regard to leisure activities, support services and support groups.. In previous social security and disability assistance consultations, the importance of choice has stood out as being a key theme, however, such choices are often diminished or non-existent in rural areas.

As previously mentioned, the local delivery team within Social Security Scotland will share locations with other services so that they are based where people currently go to ensure that they can access advice and support in existing island locations.

The Scottish Government launched the Social Security Independent Advocacy Service in January 2022 and has committed to investing £20.4 million in the service over the four years following the launch of the service.[34] The service is free and supports people who self-identify as a disabled person to access and apply for Social Security Scotland assistance. The service is independent of the Scottish Government and is delivered by VoiceAbility, a charity with 40 years’ experience of delivering independent advocacy services. Advocates from VoiceAbility can support people to have their voices heard, understand and secure their rights under the Scottish social security system, express their wishes and be fully involved in order to make informed decisions.

It is expected that the Scottish Government’s approach to delivering Scottish Adult Disability Living Allowance will help to ensure that individuals can interact with Social Security Scotland in a way that best meets their needs, while having support from friends or relatives as well as independent advice organisations, no matter where they reside in Scotland.

Contact

Email: beth.stanners@gov.scot

There is a problem

Thanks for your feedback