Draft Fisheries Assessment – The Barra Fan and Hebrides Terrace Seamount NCMPA: Fisheries management measures within Scottish Offshore Marine Protected Areas (MPAs)

These assessments look at the fishing activity occurring within each offshore MPA and SAC and assess the potential impacts of this activity on the protected features within each site. This assessment is for The Barra Fan and Hebrides Terrace Seamount NCMPA.

3. Part B Assessment – Fisheries Assessment

3.1 Fisheries assessment overview

Part B of this assessment considers if there would be a risk of the fishing activities identified in part A, at the levels identified in the relevant date range, hindering the achievement of the conservation objectives for the MPA. This is done in order to consider whether, and if so which, management measures might be appropriate for the NCMPA, taking into account all relevant statutory obligations incumbent upon the Scottish Ministers.

The fishing activities and pressures identified in Part A which have been included for assessment in Part B, are demersal trawls, pelagic fishing and anchored nets/lines. The only pressures associated with these fishing activities that have been included in Part B are;

- abrasion/disturbance of the substrate on the surface of the seabed;

- penetration and/or disturbance of the substrate below the surface of the seabed, including abrasion;

- removal of non-target species;

- removal of target species;

- changes in suspended solids (water clarity); and

- smothering and siltation rate changes (light).

3.2 Fishing Activity Descriptions

3.2.1 Existing management within The Barra Fan and Hebrides Terrace Seamount NCMPA

In compliance with Part 5, Chapter 7 of The Common Fisheries Policy and Aquaculture (Amendment etc.) (EU Exit) Statutory Instrument (S.I.) 2019 No. 753, there is a ban on the use of all bottom-contacting mobile gear below 800 m depth across all UK waters. This applies across the area of The Barra Fan and Hebrides Terrace Seamount NCMPA where the depth falls below 800 metres. Part 5 Chapter 7 of S.I. 2019, No. 753 also implements restrictions on fishing between 400 metres and 800 metres where Vulnerable Marine Ecosystems (VMEs) are present, or are likely to occur. These rules aim to minimise the impact of fishing activities on VMEs. Under The Common Fisheries Policy and Animals (Amendment etc.) (EU Exit) Regulations 2019 S.I. 2019, No. 1312 (amending S.I 2019, No. 753) there is a prohibition on the use of bottom-set gillnets, entangling nets, and trammel nets at depths greater than 200 metres for the protection of deepwater shark species. These protective measures are also applied in the North-East Atlantic Fisheries Commission (NEAFC) technical measures regulatory area (beyond European Union waters) through the same Statutory Instrument. The restrictions on the use of gillnets extends throughout the site, although in the south-eastern edge these restrictions are only seasonal.

3.2.2 Fishing activity within the NCMPA

The Barra Fan and Hebrides Terrace Seamount NCMPA overlaps ICES rectangles 41D9 41E0, 42D9, 42E0 and 42E1 in the West of Scotland (ICES Division 6a), in the Hebrides and Rockall regions. The main gear types for UK vessels are midwater trawls and demersal trawls, predominantly targeting mackerel and blue whiting.

The VMS-based estimates and ICES rectangle landings statistics indicate that over-12 m midwater trawls are the predominant UK vessels that operated within the site over the period 2015-2019.

For the over-12 m vessels, based on the VMS data from 2015-2019, midwater and demersal trawls operate predominantly in the eastern part of the site, increasing in frequency towards the eastern boundary. A small amount of hook and line activity is recorded in the south-eastern boundary corner.

In addition to UK activity, vessels from Ireland (66 vessels), Norway (49 vessels), France (15 vessels), Denmark (13 vessels), Spain (8 vessels), Faroes (7 vessels), Netherlands (7 vessels), Germany (7 vessels), Lithuania and Poland (number of vessels cannot be disclosed) may also operate in the site, based on VMS data from 2015-2020. However, it is not clear what gear types these vessels operate, nor whether they were actively fishing at the time.

3.2.3 Demersal trawls

Only bottom otter trawls operated within The Barra Fan and Hebrides Terrace Seamount NCMPA between 2015 and 2019 (Table 1). The target species for these gear types are demersal fish, industrial, molluscs or nephrops.

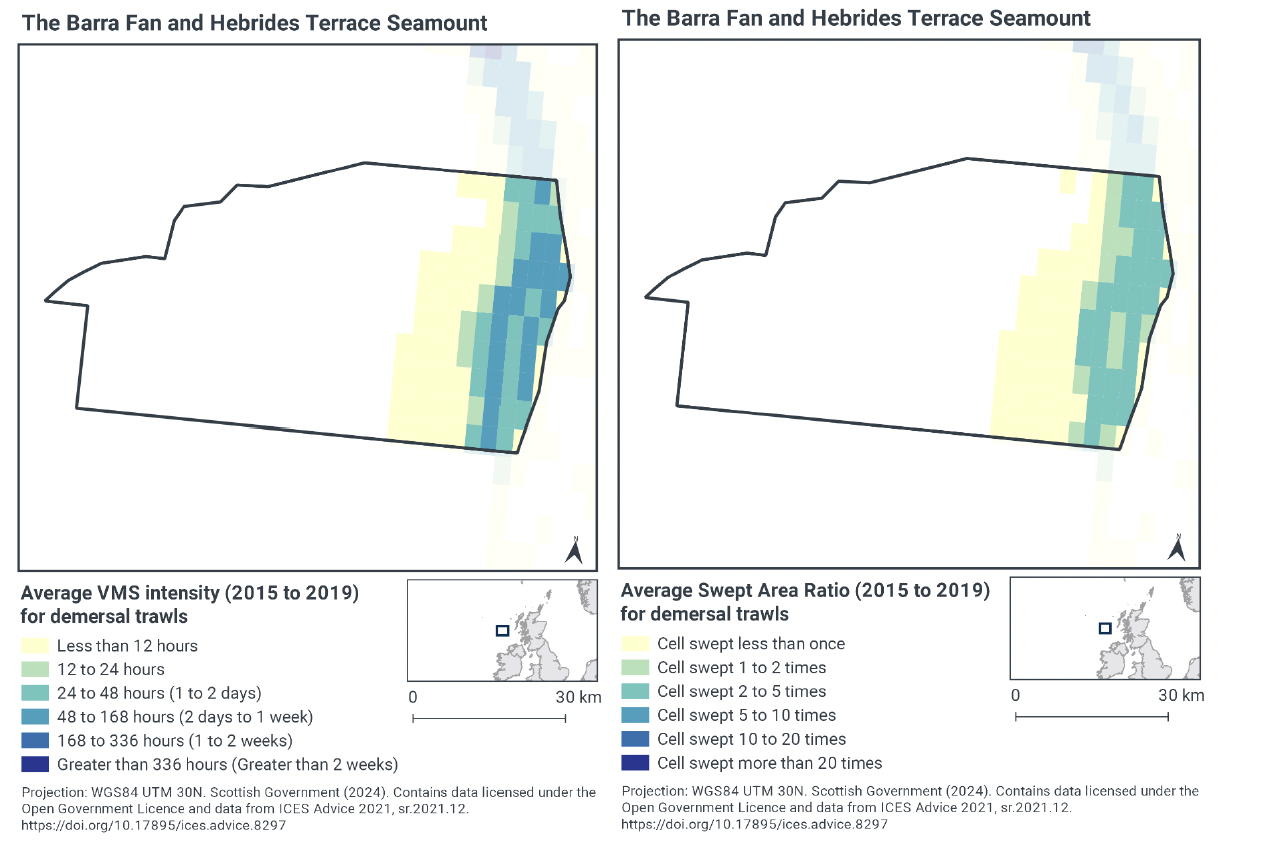

Based on the VMS, the highest intensity of demersal trawl activity within The Barra Fan and Hebrides Terrace Seamount NCMPA occurs at the east side of the site, with activity peaking at 48 - 168 hours per year per grid cell between 2015-2019 (Figure 2). The level of activity reduces away from this area, with the remainder of the site having no demersal fishing activity over this same period.

Swept-Area Ratio (SAR) information averaged over the same time period shows similar patterns of fishing intensity as the VMS data. The east side of the site has the highest SAR values, being swept 2 - 5 times per year between 2015-2019 (Figure 2). The SAR values reduce away from this area, with the majority of the site not being swept.

The area of concentrated demersal trawl activity corresponds to the shallowest area of offshore subtidal sands and gravels within the site (Figure 1).

3.2.4 Anchored nets and lines (longline fishing)

Only set longlines operated within The Barra Fan and Hebrides Terrace Seamount NCMPA between 2015 and 2019 (Table 1). The target species for these gear types are demersal fish.

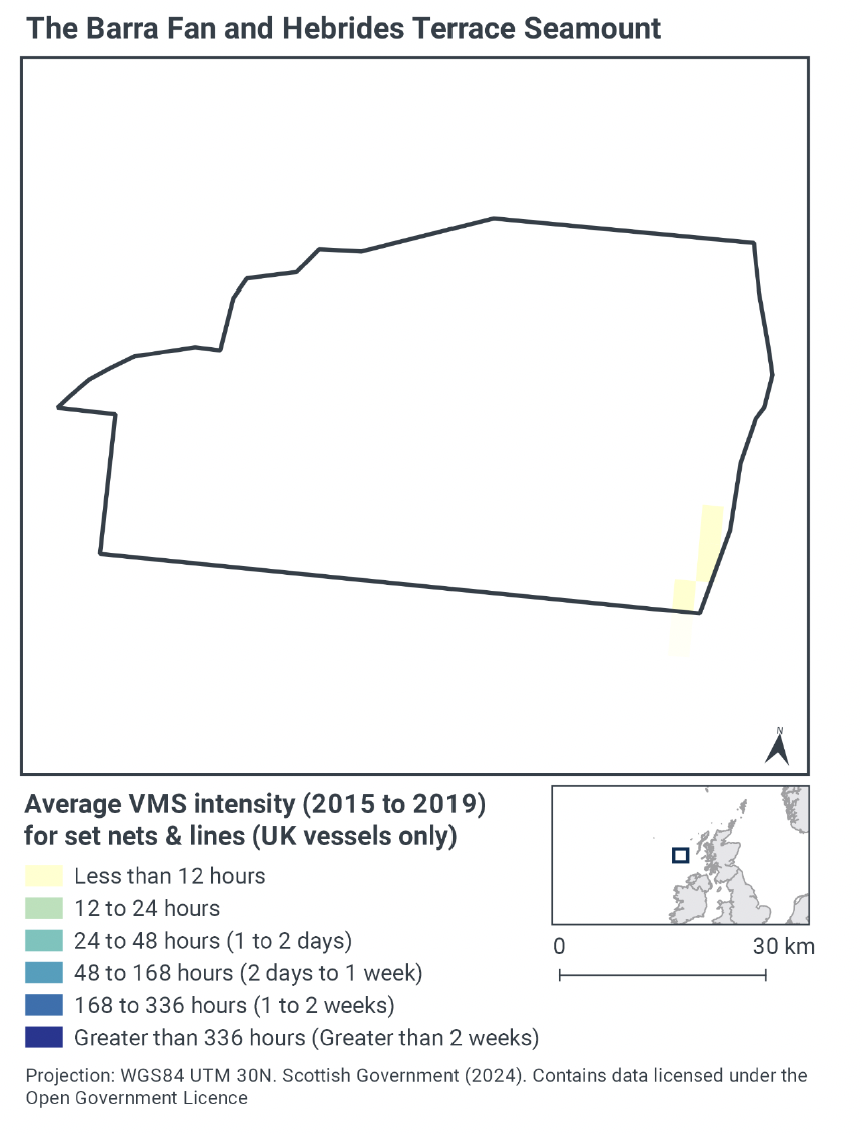

Based on the VMS, only a very limited amount of set longline activity occurs within The Barra Fan and Hebrides Terrace Seamount NCMPA, in the south-east corner of the site, with activity peaking at less than 12 hours per year per grid cell between 2015-2019 (Figure 3).

The area of concentrated line fishing activity corresponds to the area of offshore subtidal sands and gravels within the site (Figure 1).

3.2.5 Pelagic fishing

Only mid-water trawls (single) operated within The Barra Fan and Hebrides Terrace Seamount NCMPA between 2015 and 2019 (Table 1). The target species for these gear types are pelagic fish or industrial.

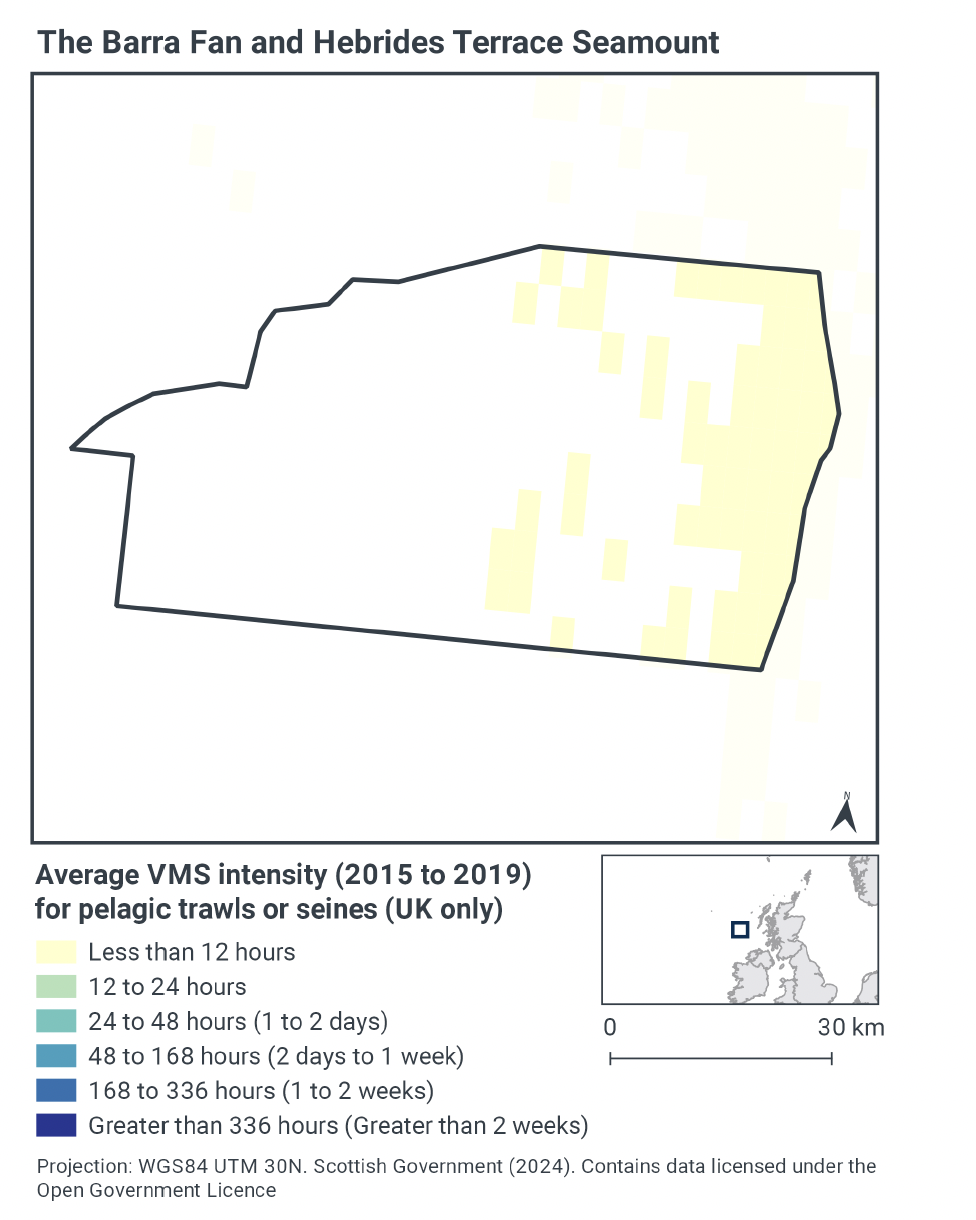

Based on the VMS, the highest intensity of pelagic fishing activity within The Barra Fan and Hebrides Terrace Seamount NCMPA occurs over the central to eastern parts of the site, with activity peaking at 48-168 hours per year per grid cell between 2015-2019 (Figure 4). The level of activity reduces away from this central strip, eastern parts of the site having highest pelagic fishing activity. This pattern of activity reflects the tendency for vessels tend to fish along the Scottish continental shelf, and The Barra Fan and Hebrides Terrace Seamount NCMPA is located on the slope at a perpendicular orientation, so fishing occurs through the site (along the shelf).

The area of concentrated line fishing activity corresponds to the area of offshore subtidal sands and gravels within the site (Figure 1).

3.2.6 Fishing activity summary

Fishing activities using demersal trawls, anchored nets/lines (longlines), and pelagic fishing all occur within The Barra Fan and Hebrides Terrace Seamount NCMPA.

Demersal trawling activity is concentrated in the east of the site, within the area of offshore subtidal sands and gravels. Very limited longline activity occurs within the site south-east corner of the site. Pelagic fishing is concentrated in the eastern and central parts of the site.

3.3 Fishing activity effects overview

The following sections explore the impacts associated with fishing activity (demersal trawls, anchored nets/lines and pelagic fishing) within The Barra Fan and Hebrides Terrace Seamount NCMPA that were considered capable of impacting the protected features. The pressures considered in the following section are:

- Abrasion/disturbance of the substrate on the surface of the seabed;

- Penetration and/or disturbance of the substrate below the surface of the seabed, including abrasion;

- Removal of non-target species;

- Removal of target species;

- Changes in suspended solids (water clarity); and

- Smothering and siltation rate changes (light).

All six pressures were exerted by demersal trawls and anchored nets/lines and two pressures (removal of non-target species and removal of target species) for pelagic fishing were considered capable of impacting the protected features of the site.

Given the similarity between ‘abrasion/disturbance of the substrate on the surface of the seabed’ and ‘penetration and/or disturbance of the substrate below the surface of the seabed’, these two pressures are considered together in the text below. ‘smothering and siltation rate changes (light)’ and ‘changes in suspended solids (water clarity)’ are also considered together. All pressures considered capable of All pressures considered capable of affecting are discussed under the aggregated fishing gear types of ‘mobile demersal gears’, ‘static demersal gears (longlines)’ and ‘pelagic fishing’.

In the absence of a detailed JNCC Advice on Operations spreadsheet for this site, the detailed pressure information for this section is based on information from the Management Options Paper for The Barra Fan and Hebrides Terrace NCMPA (2014), JNCC PAD and FeAST.

Information on the sensitivity of the protected features to each of these pressures is presented below and is taken from FeAST. At the end of this section, a summary of the overall potential impacts associated with the (demersal trawling, longlines and pelagic gear) fishing activity is presented.

3.4 Impacts associated with mobile demersal gear on The Barra Fan and Hebrides Terrace Seamount NCMPA features

In lower energy deep water locations, such as in The Barra Fan and Hebrides Terrace Seamount NCMPA, sedimentary habitats tend to be more stable and their associated fauna less tolerant of disturbance (Hiddink et al. 2006; Kaiser et al. 2006). Studies have shown that areas of mud habitats (which includes offshore deep-sea mud and burrowed mud including sea-pens) subject to mobile fishing activity, support a modified biological community with lower diversity, reduction or loss of long-lived filter-feeding species and increased abundance of opportunistic scavengers (Ball et al. 2000; Tuck et al. 1998). This effect is often greatest in the more heavily fished offshore areas suggesting that impact is related to the intensity of fishing (Ball et al. 2000). Furthermore, modelling studies suggest that the greatest impact is produced by the first pass of a trawl (Hiddink et al. 2006). Trawling on these deep-sea sedimentary habitats can cause significant decreases in organic matter content, slower organic carbon turnover, reduced meiofauna abundance, biodiversity and nematode species richness (Pusceddu et al. 2014). The use of penetrative gear over soft substrates, can further cause removal or re-stratification of sediment layers and homogenisation of sedimentary habitats (Goode et al. 2020; Martín et al. 2014). Sediment resuspension can also occur, resulting in increases in turbidity and risks of smothering to benthic fauna (Martín et al. 2014). The physical integrity of the seabed can also be altered, becoming flattened in trawled areas with less bioturbation (fewer and smaller burrows, mounds and faunal tracks) compared to non-trawled areas (Ramalho et al. 2017). Other physical impacts include scars created by the trawl doors (Goode et al. 2020). These alterations to the seafloor structure can be long lasting, with scars remaining visible for more than 10 years after trawling ceases (Goode et al. 2020). Based on the evidence above, it is likely that mobile bottom contact gear will affect the extent and distribution, and structure and function of burrowed mud (including sea-pens) and offshore deep-sea mud features, including the sediment composition and finer scale topology.

Deep-sea sea-pens, associated with burrowed mud and offshore deep-sea mud habitats, are likely to have medium sensitivity to bycatch, abrasion and penetration pressures and are highly sensitivity to heavy levels of smothering (up to 30cm) (Last et al. 2020a, 2020b). Although some sea-pen species have behavioural adaptations and can recover from minor damage (Kenchington et al. 2011; Malecha and Stone, 2009; Troffe et al. 2005), high levels of bycatch in trawl nets can occur and incidental mortality is a concern for those remaining on the seafloor (Last et al. 2020a, 2020b). Otter trawls have been found to catch the greatest frequency of sea-pens compared to other gear types, e.g., twin trawl, triple trawl, shrimp trawl, and static gears (Wareham and Edinger, 2007). Dredges can also catch high numbers of sea-pens (Pires et al. 2009). A number of studies indicate that the abundance of sea-pen species are negatively correlated with bottom trawling (Adey, 2007; Buhl-Mortensen et al. 2016; Hixon and Tissot, 2007). In addition to sea-pens, Nephrops may be an important component of the benthic community associated with offshore deep-sea mud and burrowed mud. Any fisheries, such as mobile bottom-contact gears, that greatly alter the abundance or size composition of this species may therefore have a negative impact on the biological structure of the features. This evidence further suggests that mobile bottom contact gear will likely affect the biological assemblages and biological structure of the features, resulting in impacts to the extent and distribution, and the structure and function of the burrowed mud (including sea-pens) and offshore deep-sea mud habitat features.

Similar to the above, trawling on offshore sands and gravels also can cause significant decreases in organic matter content, slower organic carbon turnover, reduced meiofauna abundance, biodiversity and nematode species richness (Pusceddu et al. 2014). Stable offshore sands and gravels often support a ‘turf’ of fragile species which are easily damaged by trawling and recover slowly (Collie et al. 2005; Foden et al. 2010). Trawling and dredging tends to cause increased mortality of fragile and long lived species and favour opportunistic, disturbance-tolerant species (Bergmann and Van Santbrink, 2000; Eleftheriou and Robertson, 1992). Some particularly sensitive species may disappear entirely (Bergmann and Van Santbrink, 2000). The net result is benthic communities modified to varying degrees relative to the un-impacted state (Bergmann and Van Santbrink, 2000; Kaiser et al. 2006). The use of penetrative gear over soft substrates, can further cause removal or re-stratification of sediment layers and homogenisation of sedimentary habitats (Goode et al. 2020; Martín et al. 2014). Sediment resuspension can also occur, resulting in increases in turbidity and risks of smothering to benthic fauna (Martín et al. 2014). Other physical impacts include scars created by the trawl doors and dislodgment or removal of boulders, rocks and biogenic substrates (Goode et al. 2020). These alterations to the seafloor structure can be long lasting, with scars remaining visible for more than 10 years after trawling ceases (Goode et al. 2020). Based on this evidence, it is likely that mobile bottom contact gear will affect the extent and distribution, and structure and function of offshore sands and gravels, including the sediment composition, finer scale topology, biological assemblages, and biological structure.

The species associated with seamount communities tend to be composed of erect and fragile species that are sensitive to physical disturbance, particularly deep-sea stony corals, gorgonians and black corals, sea anemones, hydroids and sponges (Clark et al. 2010; Clark and Tittensor, 2010). Significant reductions in stony coral cover and associated species abundance and diversity have been observed on trawled seamounts in New Zealand and Australia (Goode et al. 2020). Clark and Tittensor (2010) found that roughly 100 trawl tows can reduce coral to very low mean levels (<1%) on New Zealand seamounts. Between approximately 100 and 800 tows would remove coral cover entirely. However, mean coral cover on some seamounts can be reduced to less than 1% with far fewer tows. Single passes of trawls can themselves cause more than half of sponges and corals present to be visibly damaged (Freese et al. 1999). Mortality of species can occur both by disturbance at the seabed from trawls or through being brought to the surface, resulting in a reduction in abundance (ICES, 2010; Jennings and Kaiser, 1998; Kaiser and Spencer, 1996).

Despite some seamount taxa being more resistance to the direct effects of bottom-trawling, Goode et al. (2020) concluded that seamount benthic communities overall appear to have low resistance. Recovery from damage is estimated to be measured in decades, depending on the environmental conditions and biological variables, although the species present on seamounts can exhibit varying recovery rates (ICES, 2010; Clark et al. 2010; Goode et al. 2020). Species with higher longevity, such as habitat-forming corals and sponges, take much longer to recover. As these can form a key part of seamount communities, any impacts to those species can significantly alter the structure and function of the seamount communities feature (Goode et al. 2020). These features (deep-sea sponge aggregations, cold-water coral reefs and coral gardens), which are also designated in their own right within the West of Scotland NCMPA, are discussed below.

There is no evidence of impacted seamount communities regaining their pre-disturbance condition in terms of community composition, megafaunal abundance or species diversity (Goode et al. 2020), indicating the importance of management prior to impacts occurring where possible. Based on the evidence above, there is a high risk that mobile bottom contact gear will affect the extent and distribution of Seamount community features, as well as their structure and function.

Orange roughy (Hoplostethus atlanticus) occurs in a narrow depth band between 180-1800m (Priede, 2019), corresponding with an area about 20 nautical miles wide in the West of Scotland MPA. The species has historically been targeted in a directed demersal otter trawl fishery in deep water west of Scotland, which resulted in a strong decline in the stock (ICES, 2019a, 2020a). This fishery targeted the spawning aggregations that occur around steep slope and seamount environments, allowing very large catches to be taken over a short period of time, leading to local depletions (FeAST, 2013). However, since 2003 no direct fishery has been permitted for orange roughy, with limited bycatch allowed in mixed fisheries until 2010 when a zero total allowable catch (TAC) was implemented across all ICES subareas. In addition to the spawning aggregations around seamounts and steep slopes, Scottish deep-water trawl surveys found several juvenile cohorts were present on the gentle slopes of the continental slope (Dransfeld et al. 2013; ICES, 2019a). The species’ long life-span, slow growth rate, late maturity (27.5 years; Minto and Nolan, 2006), low fecundity and episodic recruitment characteristics contribute to its vulnerability, making the species particularly susceptible to population declines if mature adults are removed (Dransfeld et al. 2013). Fishing pressure can also disrupt the schooling behaviour of orange roughy (Clark and Tracey 1991, cited in Branch, 2001). In areas where fishing is prohibited, smaller and denser aggregations have been observed (Clark et al. 2000). Based on the evidence above, mobile bottom contact gear may affect the presence and distribution of the orange roughy feature, due to the risk associated with accidental bycatch.

Activity from demersal trawling within The Barra Fan and Hebrides Terrace Seamount NCMPA occurs moderate-high levels and the protected habitat features of the site, as described above, are highly sensitive to demersal mobile gear activity.

Given the evidence above, the impacts from demersal trawling alone within Barra Fan and the Hebrides Terrace Seamount NCMPA at the current rate of activity carry a risk of hindering the conservation objectives for burrowed mud, offshore deep-sea muds, offshore subtidal sands and gravels, orange roughy and seamount communities features, such that the extent and distribution, structure and function and supporting processes are restored. Accordingly, Scottish Ministers conclude that demersal trawls alone at current activity levels would or might hinder the achievement of the conservation objectives for The Barra Fan and Hebrides Terrace Seamount NCMPA.

3.5 Impacts associated with static demersal gear (longlines) on The Barra Fan and Hebrides Terrace Seamount NCMPA features

Only the seamount communities feature within The Barra Fan and Hebrides Terrace Seamount NCMPA is considered to be sensitive to static gear. No studies providing evidence of the effects of static gears on Scottish seamount communities were found, however impacts occurring on analogous vulnerable habitats and species, such as sponges and corals in Scottish waters are applicable (Durán Muñoz et al. 2011). Impacts can arise from hooks, lines, nets and ropes becoming entangled with corals and other fragile species, including ‘plucking’ them from the seabed during hauling (Durán Muñoz et al. 2011; Mortensen et al. 2005; OSPAR, 2010b). While the degree of damage from individual fishing operations is likely to be lower than for trawling, cumulative damage may be significant. Based on the evidence above, there is a high risk that static bottom contact gear will affect the extent and distribution of Seamount community features, as well as their structure and function.

Offshore sands and gravels within subtidal areas are not considered to be sensitive to the level of abrasion caused by static demersal gears, with minimal impact on the faunal communities and seabed structure (Tillin et al. 2010; Tyler‐Walters et al. 2009). However, in lower energy deep water locations, such as in the West of Scotland NCMPA, sediments tend to be more stable and their associated fauna less tolerant of disturbance (Hiddink et al. 2006; Kaiser et al. 2006). Bycatch of associated communities, such as invertebrates also poses a risk. Overall, the risk from low levels of static bottom contact gear on the abundance and distribution, and the structure and function of offshore sands and gravels is likely to be limited, however higher levels of fishing activity will pose a greater risk to the features and their attributes.

Bycatch of deep-sea sea-pen species (associated with offshore deep-sea mud and burrowed mud) has been recorded in gillnets and longlines, although at a lower frequency than otter trawls (Wareham and Edinger, 2007). Longline hooks of varied sizes can catch specimens of all size ranges, including larger specimens (de Moura Neves et al. 2018). If static fishing activity is low, direct impact on the habitat is likely to be minimal and seabed structure is likely to be maintained in a slightly modified state (Adey, 2007). In addition to sea-pens, nephrops may be an important component of the benthic community associated with offshore deep-sea mud and burrowed mud. Any fisheries, such as static gears, that greatly alter the abundance or size composition of this species may therefore have a negative impact on the biological structure of the features. Based on the evidence above, the risk from low levels of static bottom contact gear on the abundance and distribution, and the structure and function of burrowed mud (including sea-pens) and offshore deep-sea mud is likely to be limited, however higher levels of fishing activity will pose a greater risk to the features and their attributes.

Offshore subtidal sands and gravels are not considered to be sensitive to the level of abrasion caused by static demersal gears. The extent of direct impact on the faunal community is expected to be minimal and seabed structure will be maintained.

Orange roughy were only targeted using specialised bottom trawling techniques and the species is not commercially catchable by other gear types such as longlines (FeAST, 2013). For example, there were no catches of orange roughy in 4,998 longlines sets monitored by fisheries observers between 1991 and 2000 in the Northwest Atlantic (Kulka et al. 2001). Therefore, this species is not considered further in this section.

Activity from longlines within The Barra Fan and the Hebrides Terrace Seamount NCMPA occurs at relatively low levels and over a very limited spatial scale. However, the protected habitat features of the site, in particular seamount communities, as described above, are highly sensitive to longline activity.

Given the evidence above, the impacts from demersal static gear (longlines) alone within The Barra Fan and the Hebrides Terrace Seamount NCMPA at current activity levels, have the potential to hinder the conservation objectives of the seamount communities feature. For the protected features of burrowed mud, offshore subtidal sands and gravels, offshore deep-sea muds feature, or orange roughy, however, demersal static (longlines) gear, at current activity levels, would not hinder the achievement of the conservation objectives within The Barra Fan and the Hebrides Terrace Seamount MPA. Accordingly, Scottish Ministers conclude that demersal static gear (longlines) alone at current activity levels would or might hinder the achievement of the conservation objectives for The Barra Fan and the Hebrides Terrace Seamount MPA.

3.6 Impacts associated with pelagic gear on The Barra Fan and Hebrides Terrace Seamount features

Orange roughy have previously solely been targeted in the west of Scotland are using specialised bottom trawling techniques (FeAST, 2013), however, the species is known to feed on bentho-pelagic prey (Gordon and Duncan, 1987). Furthermore, the species can be caught by pelagic gear, for example the Faroese fleet’s fishery for orange roughy uses semi-pelagic trawls (ICES, 2020c) and in other parts of the world mid-water trawls are also used (Bensch et al. 2009). Post-larval growth in orange roughy is thought to occur in the mesopelagic, with active foraging at 700-800 m depth (Shephard et al. 2007). Spawning aggregations can also form into dynamic plumes, extending 200 m off the seabed (Branch, 2001). Although there is a zero TAC in place for orange roughy, based on the evidence above, pelagic fishing gear may affect the presence and distribution of the species due to the associated bycatch risk at all life-stages.

Based on the VMS, the highest intensity of pelagic fishing activity within The Barra Fan and Hebrides Terrace Seamount NCMPA occurs over the central to eastern parts of the site, with activity peaking at 48-168 hours per year per grid cell between 2015-2019 (Figure 4). The level of activity reduces away from this central strip, eastern parts of the site having highest pelagic fishing activity.

Given the evidence above, pelagic fishing alone within The Barra Fan and Hebrides Terrace Seamount NCMPA at current activity levels would not hinder the conservation objectives for orange roughy feature. Accordingly, Scottish Ministers conclude that pelagic fishing alone at current activity levels would not hinder the achievement of the conservation objectives for The Barra Fan and Hebrides Terrace Seamount NCMPA.

3.7 Part B Conclusion

The assessment of fishing pressures on the protected features on burrowed mud, offshore subtidal sands and gravels, offshore deep sea mud, orange roughy and seamount communities features of The Barra Fan and Hebrides Terrace Seamount NCMPA has indicated that mobile demersal (trawling) and demersal static (longline) activities could hinder the achievement of the conservation objectives for the site. As such, Scottish Ministers conclude that management measures to restrict demersal mobile (trawling) and demersal static (longlining) gears are required within The Barra Fan and Hebrides Terrace Seamount NCMPA. Section 5 contains further details on potential measures.

Scottish Ministers conclude that the remaining pelagic fishing activities, when considered in isolation and at current activity levels, will not hinder the achievement of the conservation objectives for The Barra Fan and Hebrides Terrace Seamount NCMPA.

Contact

Email: marine_biodiversity@gov.scot

There is a problem

Thanks for your feedback