Draft Fisheries Assessment – Solan Bank Reef SAC: Fisheries management measures within Scottish Offshore Marine Protected Areas (MPAs)

These assessments look at the fishing activity occurring within each offshore MPA and SAC and assess the potential impacts of this activity on the protected features within each site. This assessment is for Solan Bank Reef SAC.

3 Part B Assessment – Fisheries Assessment

3.1 Fisheries assessment overview

Part B of this assessment meets the requirements for an appropriate assessment under Article 6(3) of Council Directive 92/43/EEC of 21 May 1992 on the conservation of natural habitats and of wild fauna and flora (the Habitats Directive) and Regulation 28 of the Conservation of Offshore Marine Habitats and Species Regulations 2017, and Regulation 48(1) of the Conservation (Natural Habitats, & c.) Regulations 1994 for sites wholly or partially inshore.

The fishing activities and pressures identified in Part A, at the levels identified in the relevant date range, which have been included for assessment in Part B are mobile demersal fishing (trawls, seines, and boat dredges) and static demersal fishing (traps). The only pressures associated with these fishing activities that have been included in Part B are:

- penetration and/or disturbance of the substrate below the surface of the seabed, including abrasion;

- changes in suspended solids (water clarity) (except for creels/traps);

- smothering and siltation rate changes (light) (except for creels/traps);

- removal of target species (for creels/traps and dredges only) and

- removal of non-target species.

3.2 Fishing activity descriptions

3.2.1 Existing management within Solan Bank Reef SAC

No existing fisheries management measures or other fisheries restrictions were identified within the site.

3.2.2 Fishing activity within Solan Bank Reef SAC

The Solan Bank Reef SAC overlaps ICES rectangles 46E4 46E5, 47E4 and 47E5 in the West of Scotland (ICES Division 6a), in the North Scotland Coast region. The aggregated gear methods used in Solan Bank Reef SAC by UK vessels are demersal trawls, demersal seines, boat dredges, traps, and pelagic fishing (Table 2, in Section 2 - Part A). Pelagic fishing (mid-water trawls) was not considered capable of affecting the reef feature of Solan Bank Reef SAC as there is no contact with the seabed, and so is not considered further (see JNCC Fisheries Management Options Paper: Solan Bank Reef Special Area of Conservation). Demersal trawls, demersal seines, boat dredges, and traps are considered in more detail in the following sections.

In addition to UK activity, vessels from France (12 vessels), Ireland (8 vessels), Spain (6 vessels), Norway, Faroes, Germany, Netherlands and Lithuania (number of vessels cannot be disclosed) may also operate in the site, based on VMS data from 2015-2019. However, it is not possible to accurately determine the gear types associated with the VMS data for these non-UK vessels, or whether they were actively fishing at the time.

3.2.3 Demersal trawls

The aggregated gear method of demersal trawls includes multiple gears that operated within the Solan Bank Reef SAC between 2015 and 2019. These include bottom otter trawls, multi-rig trawls, pair trawls, and other not specified bottom trawl types. Similar pressures are exerted by the different gears used for demersal trawling, subsequently the aggregated gear type of ‘demersal trawl’ was used to map activity across the site.

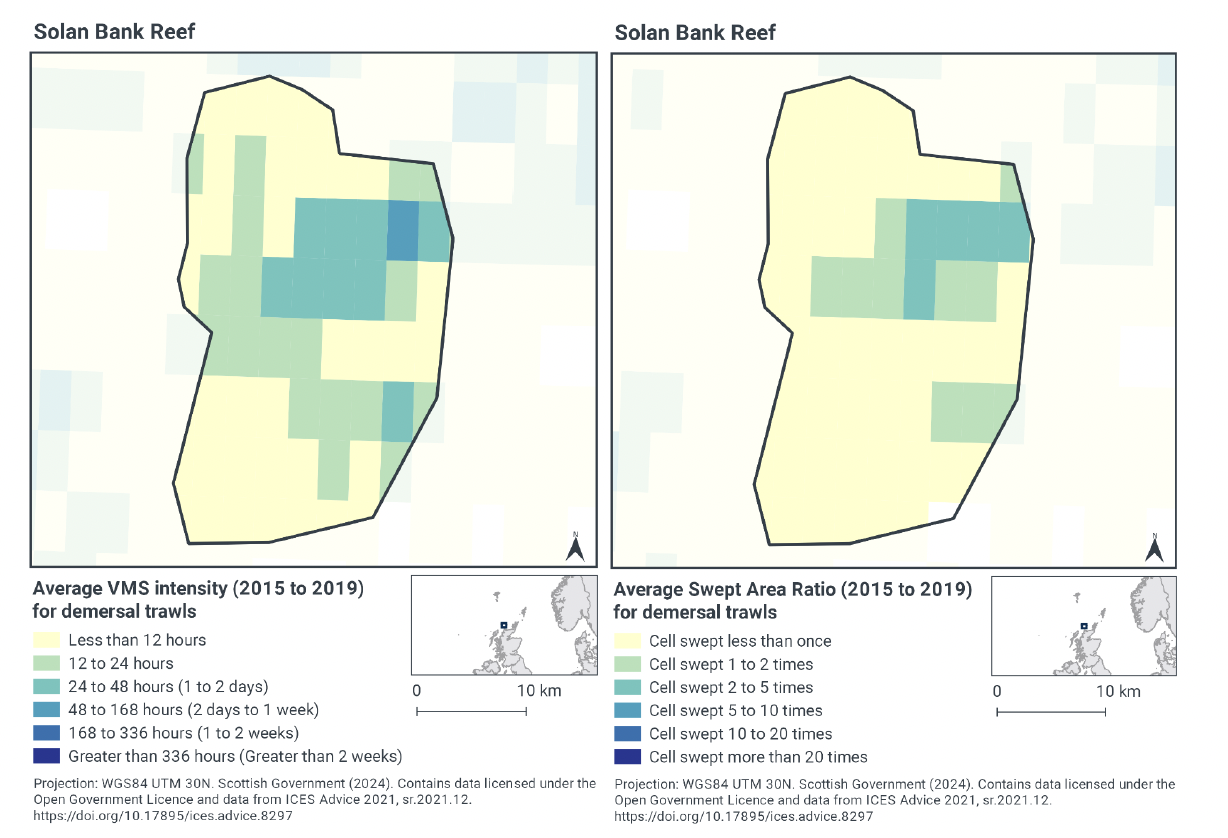

According to the VMS intensity averaged over 2015 to 2019 demersal trawling occurs throughout the site (Figure 2). Demersal trawling is concentrated in the northeast part of the site (48 – 168 fishing hours per year per grid cell), with additional areas of high concentration in the central-eastern part of the site (24 – 48 fishing hours per year per grid cell), and a band from the western part of the site into the southeast (12 – 24 hours per year per grid cell). The remainder of the site, particularly the southwest, has lower fishing intensity (less than 12 fishing hours per year per grid cell). These activity levels are comparable to fishing activity information within the NatureScot and JNCC Conservation Objectives and Advice on Operations for the site, where VMS data indicated that the region was fished at very low levels by UK demersal otter trawls (individual fishing effort grids of up to 50 hrs cumulatively over 2006 – 2009) with the effort distributed unevenly throughout the site.

Swept-Area Ratio (SAR) information averaged over the same time period shows similar patterns of fishing intensity as the VMS data (Figure 2). The highest SAR values are in the northeast (cells swept 2 – 5 or 1 – 2 times per year per grid cell) and in the central east and southeast of the site (cells swept 1 – 2 times per year per grid cell). The rest of the site had low SAR values (cells swept less than once per year per grid cell).

The locations identified as having higher fishing intensity through VMS and SAR; particularly in the northeast, central-east, and southeast; have the potential to overlap with the reef feature.

3.2.4 Demersal seines

The only gear within the aggregated demersal seine gear type operating within the Solan Bank Reef SAC between 2015 and 2019 was Scottish fly/seine gear. Fishing with this gear is referred to as the aggregated gear type of ‘demersal seines’ in the following sections to align with the approach taken for the rest of the assessment.

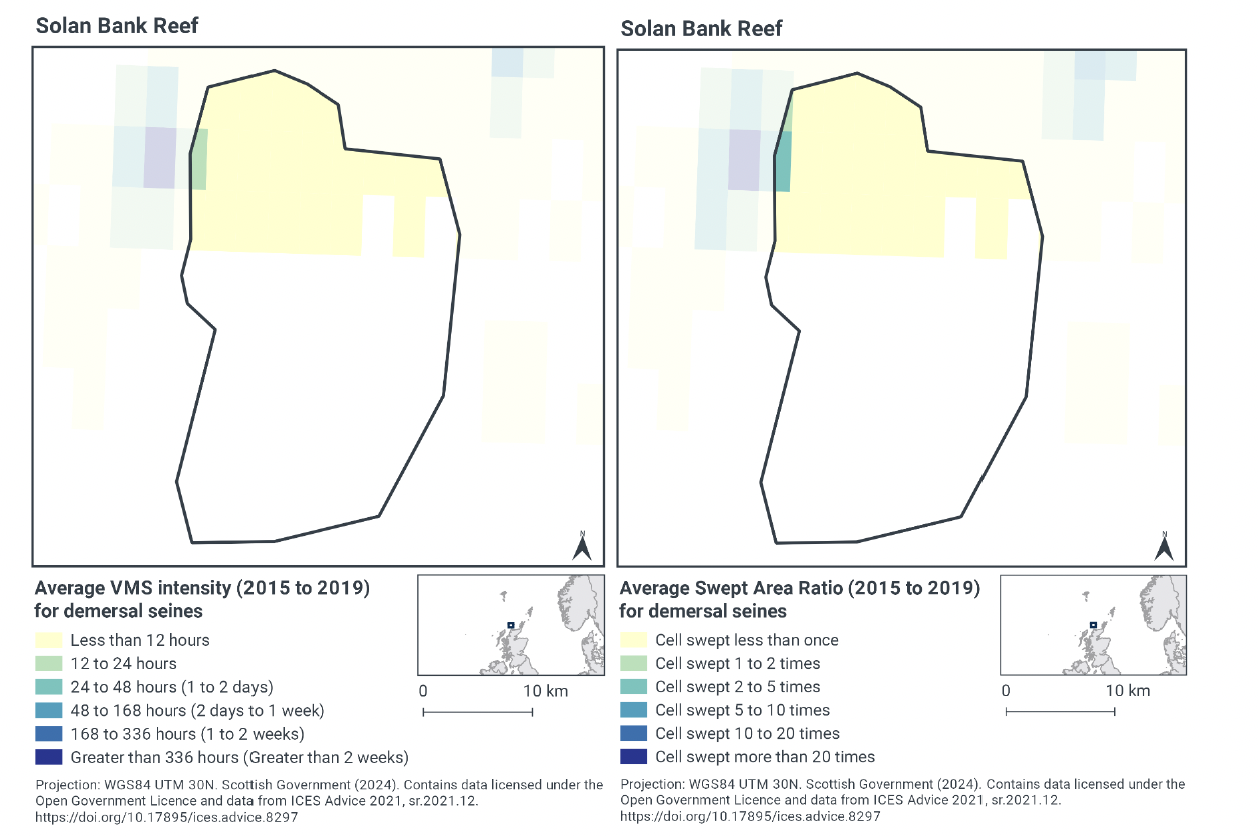

According to the VMS intensity averaged over 2015 to 2019, the distribution of demersal seines is restricted to the northern part of the site (Figure 3). The highest fishing activity is in the northwest (12 – 24 fishing hours per year per grid cell), with lower intensity fishing (less than 12 fishing hours per year per grid cell) across the north and northeast of the site.

Swept-Area Ratio (SAR) information averaged over the same time period shows similar patterns of fishing intensity as the VMS data (Figure 3). The highest SAR values are in the northwest (cells swept 2 – 5 or 1 – 2 times per year per grid cell), with lower fishing intensity across the north and northeast of the site (cells swept less than once per year per grid cell).

Overlap with the reef feature is possible across the parts of the site where fishing activity occurs.

3.2.5 Boat dredges

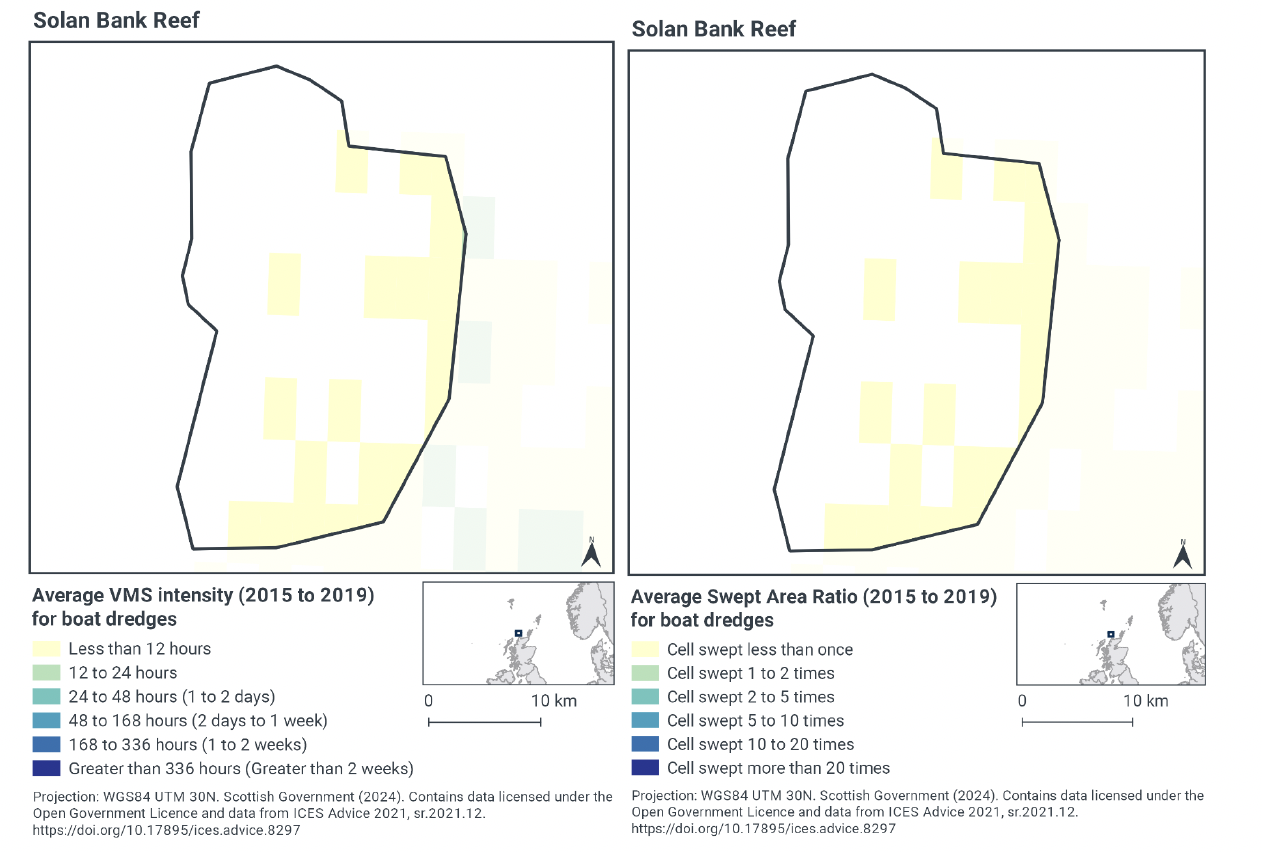

According to the VMS intensity averaged over 2015 to 2019, boat dredging happens at low levels (less than 12 fishing hours per year per grid cell) and is generally located along the eastern side of the site, spanning from the northeast to the southeast and across the southern part of the site, with some activity scattered in the central parts of the site (Figure 4).

Swept-Area Ratio (SAR) information averaged over the same time period shows similar patterns of fishing intensity as the VMS data (Figure 4), with the same spatial distribution of fished areas, all with low levels of fishing intensity (cells swept less than once).

There appears to be minimal overlap with the reef feature in areas of fishing activity, with boat dredges seeming to occur between the patches of reef feature.

3.2.6 Traps

The only gear within the aggregated traps gear type operating within the Solan Bank Reef SAC between 2015 and 2019 was pots/creels. Fishing with this gear is referred to as the aggregated gear type of ‘traps’ in the following sections to align with approach taken for the rest of the assessment.

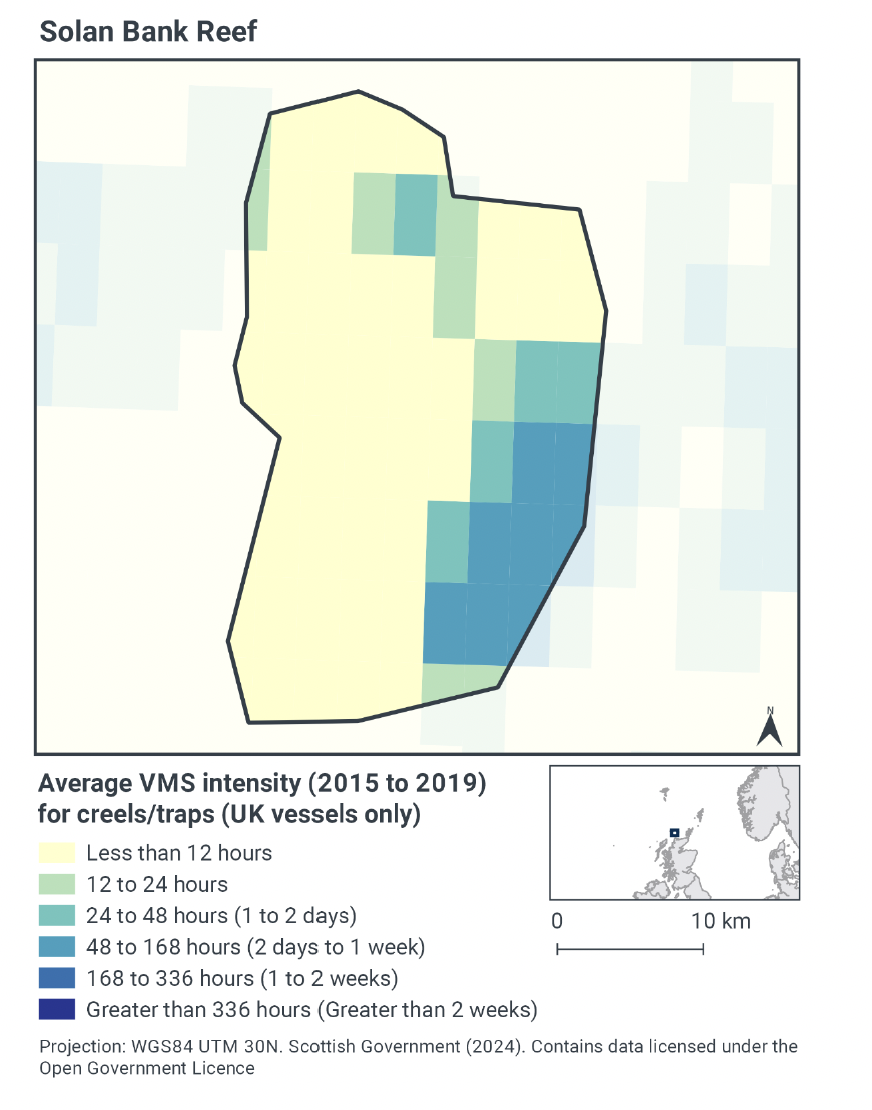

According to the VMS intensity averaged over 2015 to 2019, traps occurred throughout the site (Figure 5). The highest concentration of traps were in a band along the eastern side of the site from the east to the southeast (ranging from 48 – 168 fishing hours per year per grid cell through to 12 – 24 fishing hours per year per grid cell). Additional areas of higher fishing intensity are in the northeast (ranging from 24 – 48 fishing hours to 12 – 24 fishing hours per year per grid cell) and the northwest of the site (12 – 24 fishing hours per year per grid cell). The remainder of the site is fished at lower levels (less than 12 fishing hours per year per grid cell).

Swept-Area Ratio information is not available for static fishing, such as traps. Based on VMS data, traps have the potential to overlap with the reef feature, including in the areas of higher fishing activity.

3.2.7 Fishing activity summary

Fishing activities using demersal trawls, demersal seines, boat dredges, and traps/creels all occur within the Solan Bank Reef SAC. Demersal trawling activity occurs at higher intensity in the northeast, central-east, and in a band from the west into the southeast of the site. Demersal seines and boat dredges are more restricted in their distributions; demersal seines have the potential to overlap with the reef feature, whilst boat dredges appear to occur between patches of the feature. Traps are used throughout the site, with higher intensity along the eastern side of the site, broadly following the distribution of the reef feature.

3.3 Fishing activity effects overview

The following sections explore the pressures associated with fishing activity (demersal trawls, demersal seines, boat dredges, traps) within the Solan Bank Reef SAC that were identified as potentially having likely significant effects on the reef feature. The pressures considered in the following sections are:

- Abrasion/disturbance of the substrate on the surface of the seabed;

- Penetration and/or disturbance of the substrate below the surface of the seabed, including abrasion;

- Changes in suspended solids (water clarity) (except for traps/creels)

- Smothering and siltation rate changes (light) (except for traps/creels);

- Removal of target species (for traps/creels and dredges only) and

- Removal of non-target species.

These six pressures were associated with both or either mobile demersal fishing activity (trawls, seines, boat dredges) and static demersal fishing (traps) and are discussed under the aggregated fishing gear types of ‘mobile demersal gears’ and ‘static demersal gear’.

Given the absence of a detailed JNCC Advice on Operations spreadsheet for this site, the detailed pressure information for this section is based on information from JNCC PAD and the Advice on Operations spreadsheet for Stanton Banks which is also protected for Annex I Reefs.

3.3.1 Impacts of mobile demersal gears (trawls, seines, boat dredges) on Annex I Reef

As detailed in the JNCC Marine Pressures-Activities Database (PAD) v1.5 2022, abrasion/disturbance of the substrate on the surface of the seabed occurs where gear makes contact with the seafloor. The area affected is determined by the footprint of the gear and the amount of movement across the seabed. The different gear components will make variable contributions to the total physical disturbance of the seabed and its associated biota, and hence the pressure will vary according to factors such as gear type, design/modifications, size and weight, method of operation (including towing speed) and habitat characteristics (e.g. topography) (Lart, 2012; Polet & Depestele, 2010; Suuronen et al., 2012). Towed bottom fishing gears are used to catch species that live in, on or in association with the seabed and therefore are designed to remain in close contact with the seabed. That interaction with the seabed can lead to disturbance of the upper layers of the seabed, direct removal, damage, displacement or death of the benthic flora and fauna; short-term attraction of scavengers; and the alteration of habitat structure (Kaiser et al., 2003; Gubbay & Knapman, 1999; Sewell & Hiscock, 2005; Collie et al., 2000; Kaiser et al., 2002).

Benthic seines are generally of lighter construction as there are no trawl doors or warps, resulting in less disturbance of the seabed than trawling (Polet & Depestele, 2010; Donaldson et al., 2010; Suuronen et al., 2012). As a relative comparison of gear types, otter trawls tend to have less physical impact on the seafloor than beam trawls (and dredges) with their heavy tickler chains, although the doors of an otter trawl do create recognisable scour of the seabed (Hinz et al., 2012; Polet & Depestele, 2010; Lart, 2012; Paschen et al. 2000). Due to their penetrative nature and close contact with the seabed, scallop dredges cause substantial physical disruption to the seafloor by ploughing sediments and damaging organisms. The Newhaven dredges used by the UK king scallop fishery are likely to be one of the most damaging types of scallop dredge due to the effect of their long teeth, which can penetrate 3 – 10 cm into the seabed (Howarth & Stewart, 2014; Hinz et al., 2012).

The magnitude of the immediate response to fishing disturbance, cumulative effects and recovery times varies significantly according to factors such as the type of fishing gear and fishing intensity, the habitat and sediment type, and levels of natural disturbance and among different taxa (Collie et al., 2000; Boulcott et al., 2014; Kaiser et al., 2006; Hinz et al., 2009; Kaiser et al., 2001).

Changes in suspended solids and siltation rates may result from physical disturbance to the seabed, along with hydrodynamic action caused by the passage of towed gear, leading to entrainment and suspension of the substrate behind and around the gear components and subsequent siltation (Sewell et al., 2007; Gubbay & Knapman, 1999; Lart, 2012; Kaiser et al. 2002; Riemann & Hoffmann, 1991; O’Neill et al., 2008; Dale et al., 2011; O’Neil & Summerbell, 2011. The quantity of suspended material and its spatial and temporal persistence will depend on factors associated with the gear (e.g. weight, towing speed), sediment (e.g. particle size composition), the intensity of the activity and the background hydrographic conditions (Sewell et al., 2007; Kaiser et al., 2002).

Turbid plumes can reduce light levels while sediment remobilisation and deposition can affect the settlement, feeding and survival of biota through smothering of feeding and respiratory organs. Prolonged exposure of an area to these pressures may result in changes in sediment composition (Sewell et al., 2007; Gubbay & Knapman, 1999; Kaiser et al., 2002; O’Neil & Summerbell, 2011).

Bycatch (i.e. discarded catch) is associated with almost all fishing activities and is related to factors such as gear type and its design (i.e. its selectivity), the target species and effort. There are significant concerns over the impacts of discards on marine ecosystems including changes in population abundance and demographics of affected species and altered species assemblages and food web structures (Alverson et al., 1994; Kaiser et al., 2001). As with other benthic towed gears, discarding of fish species from demersal seine net fisheries can be significant (Polet & Depestele, 2010; ICES, 2011). These are relatively few studies of the non-fish bycatch composition for demersal seines, however, it is probably similar to that of demersal trawls e.g. crustaceans and other invertebrates, etc., although quantities of such bycatch are likely to be lower than that of other gear types such as beam trawls (Suuronen et al., 2012; ICES, 2011; Donaldson et al., 2010; Walsh & Winger, 2011). Mixed-species and shrimp/prawn demersal trawl fisheries are associated with the highest rates of discarding and pose the most complex problems to resolve (Alverson et al., 1994; Feekings et al., 2012; Catchpole et al., 2005). Benthic trawls most frequently result in bycatch of fish crustaceans and other invertebrates and less frequently turtles and birds (Gubbay & Knapman, 1999; Sewell & Hiscock, 2005; ICES, 2013; Pierpoint, 2000; Bergmann & Moore, 2001; Catchpole et al., 2005; Tulp et al., 2005). Dredging can result in bycatch of fish, crustaceans and other invertebrates, turtles and even marine mammals (Gubbay & Knapman, 1999; Sewell & Hiscock 2005; NOAA Fisheries, 2012; Hinz et al., 2012; Craven et al., 2013). Of all the fishing gears, scallop dredges are considered to the most damaging to non-target benthic communities (MESL & NE, 2013).

Demersal seines, trawling and dredging may also affect the reef feature through removal of target species. Dredges are used to collect a variety of shellfish (e.g. scallops) which may themselves be part of the feature or may be species forming part of the biotope or associated with the wider community and ecosystem function (Gubbay & Knapman, 1999; Sewell & K. Hiscock, 2005; JNCC & Natural England, 2011).

As detailed in the JNCC Fisheries Management Options Paper: Solan Bank Reef Special Area of Conservation, whilst it is unlikely that mobile bottom contact gear can affect the long-term natural distribution of bedrock and stony reef features, there is evidence to indicate that the use of bottom contacting mobile gears can impact the structure and function of the habitat and the long term survival of its associated species. The use of towed fishing gears is likely to cause damage or death of fragile, erect species, such as sponges and corals (Løkkeborg 2005; Freese et al., 1999). Other species such as hydroids, anemones, bryozoans, tunicates, and echinoderms may also be vulnerable (McConnaughey et al., 2000; Sewell & Hiscock, 2005). Where fragile, slow growing species occur, even low levels of fishing have the potential to change the structure and function of the habitats and may result in the loss of some characteristic species.

According to the NatureScot and JNCC Conservation Objectives and Advice on Operations for the site, the reef at Solan Bank is exposed to physical disturbance and abrasion at low levels due to otter trawling and creeling. Although it is likely that bottom trawlers avoid the hard substrate to prevent damage to their gear, according to the NatureScot and JNCC Conservation Objectives and Advice on Operations, the best available evidence (as at 2012) was not of sufficient spatial resolution to confirm this.

The most recent NatureScot and JNCC Conservation Objectives and Advice on Operations indicated that mobile demersal fishing (including demersal trawling, demersal seining and boat dredges) poses a moderate risk of damage to Solan Bank Reef habitat. The Solan Bank reefs and associated biological communities were assessed as moderately vulnerable to 1) physical damage through physical disturbance or abrasion; and 2) biological disturbance through selective extraction of species, resulting from demersal fishing.

Considering the current levels of mobile demersal trawl and seine fishing activity within the site, and information on the impacts of abrasion/disturbance of the substrate on the surface of the seabed and removal of non-target species, demersal trawling and demersal seining are causes for concern for the reef feature of Solan Bank Reef SAC. This aligns with the 2023 JNCC Fisheries Management Options Paper: Solan Bank Reef Special Area of Conservation, which advises that the option of ‘no additional management’ for mobile demersal fishing would pose significant risk of not achieving the conservation objectives for the reef feature.

There is a risk that abrasion/disturbance of the substrate on the surface of the seabed caused by mobile demersal gear (trawls, seines, and boat dredges) may not help the achievement of favourable condition. Even if the impacts across gear types vary, mobile demersal fishing gears are likely to have negative impacts on biological communities across the Solan Bank Reef SAC and these gears are not considered compatible with maintaining the Annex I reef feature in, or restoring it to, favourable condition.

Through physical impacts from gear interacting with the seabed, mobile demersal gear has the potential to affect maintaining or restoring reef in/to favourable condition, such that the natural environmental quality and processes supporting the habitat, the extent of the habitat on site, and the physical structure, community structure, function, diversity and distribution of the habitat and typical species representative of the reef in the Northern North Sea regional sea are maintained or restored. Accordingly, Scottish Ministers conclude that demersal trawls, seines, and dredges alone are not compatible with the conservation objectives of the site and may result in an adverse effect on site integrity.

3.3.2 Impacts of static demersal gears (traps) on Annex I Reef

As detailed in the JNCC Marine Pressures-Activities Database (PAD) v1.5 2022, abrasion/disturbance of the substrate on the surface of the seabed can result from surface disturbance caused by contact between the pots/traps and any associated ground ropes and anchors. This occurs during setting of the pots/traps and/or by movement of the gear over the seabed, for example during rough weather or during retrieval. Such physical disturbance can result in epifauna, especially emergent species such as erect sponges and coral, being dislodged (including snagged on the pot) or damaged, although there are limited studies of such effects (Lart, 2012; Polet & Depestele, 2010; Walmsley et al., 2015; Gubbay & Knapman, 1999; Sewell & Hiscock, 2005; Coleman et al., 2013). The individual impact of a single fishing operation may be slight but cumulative damage may be significant (Eno et al., 2001; Foden et al., 2010). It was recently suggested that pot fishing at lower pot densities did not have negative impacts on seafloor communities, although negative effects did occur at higher pot densities (e.g. where pot densities exceeded 15 – 25 pots per 0.25 km2: Rees et al. (2021).

Bycatch (i.e. discarded catch) is associated with almost all fishing activities and is related to factors such as the gear type and its design (i.e. its selectivity), the targeted species and effort. There are significant concerns over the impacts of discards on marine ecosystems, including changes in population abundance and demographics of affected species and altered species assemblages and food web structures (Alverson et al., 1994; Kaiser et al., 2001). Whilst generally considered one of the most selective gear types, pots/traps are associated with bycatch, including of non-target crustaceans (berried females of target species are also considered bycatch in some fisheries, for example), fish, mammals (e.g. seals in cod pots) and potentially some bird species (ICES, 2013; Sewell & Hiscock, 2005; Königson et al., 2015). Bycatch survival rates are generally higher for pots than other fishing gear types (Suuronen et al., 2012; Seafish, 2014). However, the associated ropes can also result in entanglement of turtles and mammals (Sewell and Hiscock, 2005; Pierpoint, 2000). Salmon nets and fyke nets have been associated with bycatch of birds and mammals (Murray et al., 1994; Cullen & McCarthy, 2002; ICES, 2013; Lunneryd et al., 2005), as well as non-target fish species.

As detailed in the JNCC Fisheries Management Options Paper: Solan Bank Reef Special Area of Conservation, mechanical impacts of static gear (e.g., weights and anchors hitting the seabed, hauling gear over seabed, rubbing/entangling effects of ropes) can damage some species (Eno et al., 1996). Other species appear to be resilient to individual fishing operations, but the effects of high fishing intensity are unknown (Eno et al. 2001). Recovery will be slow (Foden et al., 2010) resulting in significant reduction or even loss of characteristic species. The individual impact of a single fishing operation may be slight but cumulative damage may be significant (Eno et al., 2001; Foden et al., 2010). It was recently suggested that pot fishing at lower pot densities did not have negative impacts on seafloor communities, although negative effects did occur at higher pot densities (e.g. where pot densities exceeded 15 – 25 pots per 0.25 km2: Rees et al. (2021).

Considering the current levels of static demersal trap fishing within the site, and information on the impacts of abrasion/disturbance of the substrate on the surface of the seabed and removal on non-target species, trap fishing is not currently a cause of concern for the reef feature of Solan Bank Reef SAC. This aligns with the 2023 JNCC Fisheries Management Options Paper: Solan Bank Reef Special Area of Conservation, which advises that the option of ‘no additional management’ is considered sufficient for bottom contacting static gear (including the aggregated trap gear type) to achieve the conservation objectives for the reef feature. However, if monitoring showed evidence of detrimental effects as a result of static gear activity in the future, additional management may be required.

Given the evidence above, the impacts of abrasion/disturbance of the substrate on the surface of the seabed and removal of non-target species from demersal static gear (traps) alone within Solan Bank Reef SAC at current activity levels would not affect maintaining or restoring the reef feature in/to favourable condition, such that the natural environmental quality and processes supporting the habitat, the extent of the habitat on site, and the physical structure, community structure, function, diversity and distribution of the habitat and typical species representative of the reef in the Northern North Sea regional sea are maintained or restored. Accordingly, Scottish Ministers conclude that demersal static gear (traps) alone are compatible with the conservation objectives of the site at current activity levels and will not result in an adverse effect on site integrity.

3.4 Part B Conclusion

The assessment of fishing pressures at current activity levels on reef features of the Solan Bank Reef SAC has indicated that an adverse effect on site integrity cannot be ruled out where mobile demersal fishing (demersal trawl, demersal seine, and boat dredge) activities occur. As such Scottish Ministers conclude that management measures to restrict mobile demersal gears would be required within Solan Bank Reef SAC to ensure the integrity of the site. Section 5 contains further details on potential measures.

Scottish Ministers conclude that the remaining static demersal fishing activities (traps), when considered in isolation and at current levels, are compatible with the conservation objectives of the site and will not result in an adverse effect on site integrity for Solan Bank Reef SAC.

Contact

Email: marine_biodiversity@gov.scot

There is a problem

Thanks for your feedback