Draft Fisheries Assessment – Wyville-Thomson Ridge SAC: Fisheries management measures within Scottish Offshore Marine Protected Areas (MPAs)

These assessments look at the fishing activity occurring within each offshore MPA and SAC and assess the potential impacts of this activity on the protected features within each site. This assessment is for Wyville-Thomson Ridge SAC.

3. Part B Assessment – Fisheries Assessment

3.1 Fisheries Assessment Overview

Part B of this assessment meets the requirements for an appropriate assessment under Article 6(3) of the Habitats Directive 1992, and Regulation 28 of the Conservation of Offshore Marine Habitats and Species Regulations 2017.

The fishing activities and pressures identified in Part A, at the levels identified in the relevant date range, which have been included for assessment in Part B , are demersal trawls. The only pressures associated with these fishing activities that have been included in Part B are:

- abrasion/disturbance of the substrate on the seabed,

- penetration and/or disturbance of the substrate below the surface of the seabed, including abrasion,

- smothering and siltation rate changes, removal of target species and

- removal of non-target species.

3.2 Fisheries Activity Descriptions

3.2.1 Existing fisheries management within Wyville Thomson Ridge SAC

The Wyville Thomson Ridge SAC ranges from over 1,000 m in depth, up to less than 400 m at the summit.

Under Regulation (EU) 2019/1241, article 9 (as amended by S.I 2019/1312 and S.I. 2020/1542), fishing with bottom-set gillnets, entangling nets, and trammel nets below 200 m is prohibited.

Regulation (EU) 2016/2336, article 8 (as amended by S.I 2019/753) prohibits the use of bottom trawls below 800 m. This applies to the north and southern sides of the ridge which can reach depths of 1,000 m.

3.2.2 Fishing activity with Wyville Thomson Ridge SAC

The Wyville-Thomson Ridge SAC overlaps ICES rectangles 48E2, 48E3, 48E4, 49E2 and 49E3 in both the West of Scotland (ICES Division 6a) and Faroes Grounds (ICES Division 5b), in the North Scotland Coast, Faroe Shetland Channel and Bailey regions.

The gears identified as occurring within the site are demersal trawl, pelagic trawl and longline fishing. As outlined above, pelagic fishing (mid-water trawls) was not considered capable of affecting the reef feature of Wyville Thomson Ridge SAC as there is no contact with the seabed, and so is not considered further.

In addition to UK activity, vessels from Faroes (16 vessels), Netherlands (6 vessels), and Norway (6 vessels), France, Germany and Spain (number of vessels cannot be disclosed) may also operate in the site, based on VMS data from 2015-2019. However, it is not possible to accurately determine the gear types associated with the VMS data for these non-UK vessels, or whether they were actively fishing at the time.

3.2.3 Demersal Trawls

The aggregated gear method of demersal trawls captures the two trawl gears (bottom otter trawl and multi-rig trawl) that were found to have operated within the Wyville Thomson Ridge SAC between 2015 and 2019. The target species for these gear types are demersal fish. As both these gear types exert similar pressures, the aggregated gear type of ‘demersal trawl’ was used to map activity across the site.

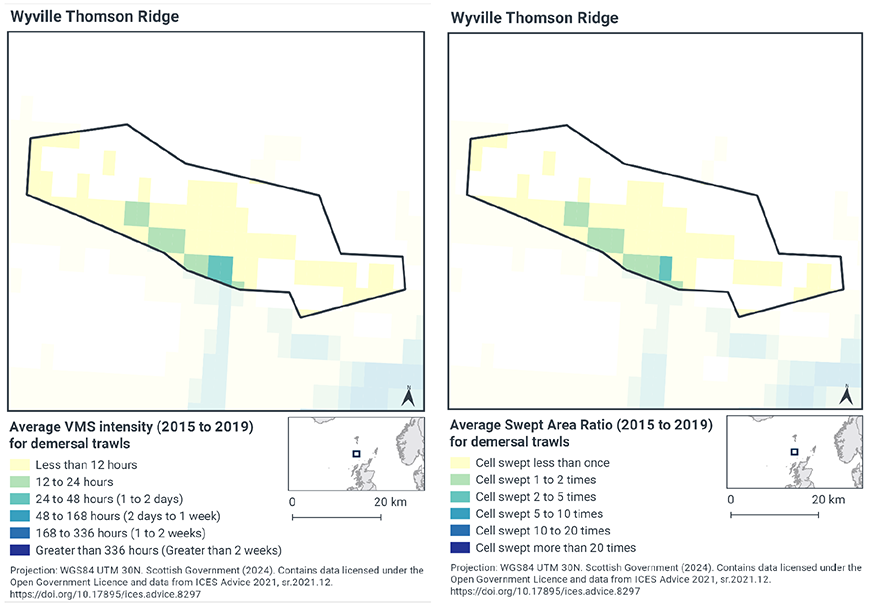

According to VMS intensity averaged over 2015 to 2019 within the site, less than 12 hours of demersal trawling activity per year per cell occurs across the mid-northern section of the site, with 12-48 hours activity per year per cell identified in the southern region (Figure 2).

Swept-Area Ratio (SAR) information averaged over the same time period shows similar patterns of fishing intensity as the VMS data (Figure 2) with cells being swept less than five times per year, with the majority of the site being swept less than once.

3.2.4 Anchored Net/Line Fishing

The aggregated gear method of anchored net/line fishing captures the two demersal static gears (set longlines and longlines unspecified) that were found to have operated within the Wyville Thomson Ridge SAC between 2015 and 2019. The target species for these gear types are demersal fish. The aggregated gear type of anchored net/line fishing was used to map activity across the site.

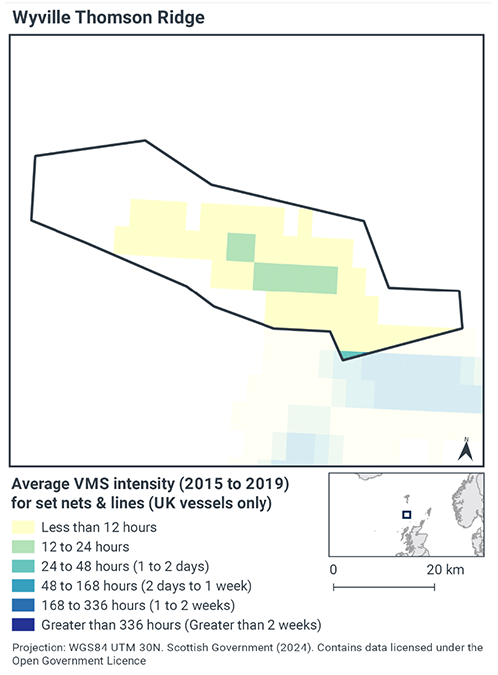

According to VMS intensity averaged over 2015 to 2019 within the site, less than 12 hours per year per cell of anchored net/line fishing activity per year occurs across the mid-south west section of the site, with 12-24 hours per year per cell identified in the southern region (Figure 3).

3.2.5 Summary of fishing activity within Wyville Thomson Ridge SAC

The fishing activity identified as occurring within Wyville Thomson Ridge SAC is demersal trawling through bottom otter trawl and longline fishing. For the majority of the area where demersal trawl occurred in the site the gear was used for less than 12 hours per year per cell on average, with some cells calculated at 12-48 hours per year per cell on average. This was also the case for longline fishing, with the majority of the area where the gear was used fished for less than 12 hours per year per cell on average, with some areas seeing an average 12-24 hours per year per cell.

3.3 Fishing activity effects overview

The following sections explore the pressures associated with fishing activity (demersal trawls and anchored nets/lines) within the Wyville Thomson Ridge SAC that were identified as potentially having likely significant effects (LSE) on the reef feature. The pressures considered in the following sections are:

- Abrasion/disturbance of the substrate on the seabed;

- Penetration and/or disturbance of the substrate below the surface of the seabed, including abrasion;

- Smothering and siltation rate changes (light);

- Removal of target species; and

- Removal of non-target species.

All five pressures, as exerted by mobile demersal fishing (trawls), were considered to have the potential for LSE. For static demersal fishing (anchored nets/lines), only abrasion/disturbance of the substrate on the surface of the seabed, removal of target species, and removal of non-target species were considered to have the potential for LSE.

Given the similarity between ‘abrasion/disturbance of the substrate on the surface of the seabed’ and ‘penetration and/or disturbance of the substrate below the surface of the seabed’, these two pressures are considered together in the text below. All pressures with the potential for LSE are discussed under the aggregated fishing gear types of ‘mobile demersal gears’ and ‘static demersal gear’.

The detailed pressure information for this section is based on the JNCC Advice on Operations for Wyville Thomson Ridge SAC, and the JNCC Fisheries Management Options Paper for Wyville Thomson Ridge SAC.

3.3.1 Impacts of mobile demersal gears (trawls) on Annex I Reef

As detailed in the JNCC Advice on Operations for Wyville Thomson Ridge SAC, abrasion/disturbance of the surface of the substrate and penetration and/or disturbance of the substrate below the surface of the seabed, including abrasion, occur where the gear makes contact with the seafloor. The area affected is determined by the footprint of the gear and the amount of movement across the seabed. The different gear components will make variable contributions to the total physical disturbance of the seabed and its associated biota, and hence the pressure will vary according to factors such as gear type, design/modifications, size and weight, method of operation (including towing speed) and habitat characteristics (e.g. topography) (Lart, 2012, Polet & Depestele 2010, Suuronen, et al. 2012). Towed bottom fishing gears are used to catch species that live in, on or in association with the seabed and therefore are designed to remain in close contact with the seabed. That interaction with the seabed can lead to disturbance of the upper layers of the seabed, damage, displacement or death of the benthic flora and fauna; short-term attraction of scavengers; and the alteration of habitat structure (Kaiser M. J., Collie, Hall, Jenning, & Poiner, 2003) (Gubbay & Knapman, 1999) (Sewell & Hiscock, Effects of fishing within UK European Marine Sites: Guidance for nature conservation agencies, 2005); (Collie, Hall, Kaiser, & Poiner , 2000); (Kaiser M. J., Collie, Hall, Jennings, & Poiner, 2002).

As a relative comparison of gear types, otter trawls tend to have less physical impact on the seafloor than beam trawls (and dredges) with the heavy tickler chains of beam trawls able to penetrate up to 8 cm into the seabed, although the doors of an otter trawl do create recognisable scour of the seabed (Hinz, Murray, Malcom, & Kaiser, 2012); (Polet & Depestele, 2010);(Lart, 2012); (Paschen, Richter, & Köpnick, 2000). The magnitude of the immediate response to fishing disturbance, cumulative effects and recovery times varies significantly according to factors such as the type of fishing gear and fishing intensity, the habitat and sediment type, levels of natural disturbance and among different taxa (Collie, Hall, Kaiser, & Poiner , 2000); (Boulcott, Millar , & Fryer, 2014)(Kaiser, et al., 2006); (Hinz, Prieto, & Kaiser, 2009); (Kaiser M. J., Collie, Hall, Jenning, & Poiner, 2003).

Smothering and siltation rate changes (light) may result from physical disturbance of the sediment, along with hydrodynamic action caused by the passage of towed gear, leading to entrainment and suspension of the substrate behind and around the gear components and subsequent siltation (Gubbay & Knapman, 1999); (Lart, 2012); (Sewell, Harris, Hinz, Votier, & Hiscock, 2007); (Kaiser M. J., Collie, Hall, Jennings, & Poiner, 2002); (Riemann & Hoffmann, 1991); (O'Neill, Summerbell, & Breen, 2008); (Dale, Boulcott, & Sherwin, 2011); (O'Neil & Summerbell, 2011). The quantity of suspended material, its spatial and temporal persistence and subsequent patterns of deposition will depend on factors associated with the gear (such as type/design, weight, towing speed), sediment (particle size, composition, compactness), the intensity of the activity and the background hydrographic conditions, (Sewell, Harris, Hinz, Votier, & Hiscock, 2007)(Kaiser M. J., Collie, Hall, Jennings, & Poiner, 2002); (Dale, Boulcott, & Sherwin, 2011); (O'Neil & Summerbell, 2011). Sediment remobilisation and deposition can affect the settlement, feeding, and survival of biota through smothering of feeding and respiratory organs. Prolonged exposure of an area to the pressure may result in changes in sediment composition, (Gubbay & Knapman, 1999); (Kaiser M. J., Collie, Hall, Jennings, & Poiner, 2002); (O'Neil & Summerbell, 2011); (Kaiser M. J., Collie, Hall, Jenning, & Poiner, 2003); (Sewell, Harris, Hinz, Votier, & Hiscock, 2007).

Demersal trawls target a range of demersal fish species and also remove species which may themselves be of conservation importance or may form part of the biotope (e.g. Norway lobster - Nephrops norvegicus) or wider community composition associated with protected features/sub-features. As part of targeted fisheries, incidental non target catch may also be retained and landed due to its commercial value (e.g. spiny lobster (Palinurus elephas), lobsters (Homarus gammarus), crabs, scallops (Pecten spp.), etc). These species may be considered part of the wider community composition associated with features or sub-features of designated sites or may themselves be of conservation importance (e.g. crawfish) (Sewell & Hiscock, Effects of fishing within UK European Marine Sites: Guidance for nature conservation agencies, 2005); (Joint Nature Conservation Council, Natural England, 2011).

Bycatch (i.e. discarded catch) is associated with almost all fishing activities and is related to factors such as the gear type and its design (i.e. its selectivity), the targeted species and effort. There are significant concerns over the impacts of discards on marine ecosystems, including changes in population abundance and demographics of affected species and altered species assemblages and food web structures (Alverson, Freeberg, Murawski, & Pope, 1994); (Kaiser M. J., Collie, Hall, Jenning, & Poiner, 2003). Mixed-species and shrimp/prawn demersal trawl fisheries are associated with the highest rates of discarding and pose the most complex problems to resolve (Alverson et al., 1994; Feekings et al., 2012; Catchpole et al., 2005). Benthic trawls most frequently result in bycatch of fish, crustaceans and other invertebrates and less frequently turtles and birds (Gubbay & Knapman, 1999); (Sewell & Hiscock, Effects of fishing within UK European Marine Sites: Guidance for nature conservation agencies, 2005); (ICES, 2013); (Pierpoint, 2000); (Bergmann & Moore, 2001); (Catchpole, Frid, & Gray, 2005)(Tulp, Piet, Quirijns, Rijnsdorp, & Lindeboom, 2005).

Whilst it is unlikely that mobile bottom contact gear can affect the long-term natural distribution of the reef features, there is evidence to indicate that the use of bottom contacting mobile gears can impact the structure and function of the habitat and the long term survival of its associated species.

The use of towed fishing gears is likely to cause damage or death of fragile, erect species, such as sponges and corals (Løkkeborg, 2005; Freese et al. 1999). Other species such as hydroids, anemones, bryozoans, tunicates, and echinoderms may also be vulnerable (McConnaughey et al. 2000; Sewell and Hiscock, 2005). Where fragile, slow growing species occur, even low levels of fishing have the potential to change the structure and function of the habitats and may result in the loss of some characteristic species.

Through physical impacts from gear interacting with the seabed, mobile demersal trawl activity has the potential to affect restoration of the reef to favourable condition, such that the extent and distribution of the qualifying habitat in the site; the structure and function of the qualifying habitat in the site; and the supporting processes on which the qualifying habitat relies are restored.

This evidence highlights the risk of demersal mobile gear to the stony and bedrock reef features even at a low level of activity. Accordingly, Scottish Ministers conclude that demersal trawls are not compatible with the conservation objectives of the site and may result in an adverse effect on site integrity.

3.3.2 Impacts of static demersal gear (anchored nets/lines) on Annex I Reef

As detailed in the JNCC Advice on Operations for Wyville Thomson Ridge SAC, abrasion/disturbance of the surface of the substrate and penetration and/or disturbance of the substrate below the surface of the seabed, including abrasion can both be associated with anchored nets/lines fishing. Surface abrasion can result from surface disturbance caused by contact between the lines themselves and any footropes and anchors. This is most likely to happen during retrieval of the gear if it is dragged along the seabed before ascent, although disturbance of the seabed can occur while the gear is fishing if movement (particularly of any anchors) occurs during rough weather, for example, or otherwise. Such physical disturbance can result in epifauna, especially emergent species such as erect sponges and coral, being dislodged (including snagged in the nets or lines) or damaged, although there are limited studies of such effects(Lart, 2012); (Polet & Depestele, 2010) (Sewell & Hiscock, Effects of fishing within UK European Marine Sites: Guidance for nature conservation agencies, 2005); (Suuronen, et al., 2012)(Auster & Langton, 1998)).

For removal of target species, anchored nets and lines are used to target pelagic, demersal and benthic fish and crustacean species. Anchored nets and lines can result in the targeted removal of features of conservation importance (e.g. spiny lobster (Palinurus elephas), salmon (Salmo salar)) and also species which form part of the community composition of features or sub-features e.g. species such as crab and lobster (Homarus gammarus) which may be associated with reef features and other species such as whelks ((Gubbay & Knapman, 1999); (Sewell & Hiscock, Effects of fishing within UK European Marine Sites: Guidance for nature conservation agencies, 2005); (Joint Nature Conservation Council, Natural England, 2011).

In terms of the removal of non-target species, although highly selective for the larger pelagic fish, longlines can cause by-catch of large and frequently long-lived species including invertebrates ((Hall, Alverson, & Metuzals, 2000); (Gubbay & Knapman, 1999);(Sewell & Hiscock, Effects of fishing within UK European Marine Sites: Guidance for nature conservation agencies, 2005); (Dayton, Thrush, Agardy, & Hofman, 1995)). In the UK, long line fishing is operated on a small scale by only a few inshore vessels in different parts of the country. Anchored nets, including gill and trammel nets, can result in the entanglement and bycatch of a range of fauna including mammals, turtles, fish, elasmobranchs, crustaceans and other invertebrates and birds (Gubbay & Knapman, 1999; ICES, 2013; WWT, 2012; Žydelis et al., 2009; Pierpoint, 2000; Oliver et al., 2015), the consequences of which can be significant to species and populations (Reeves et al., 2013; Furness, 2003; Tasker et al., 2000). Further, ghost fishing has been associated with lost lines and anchored nets gear (Matsuoka, Nakashima, & Nagasawa, 2005).

The mechanical impacts of static gear (e.g., weights and anchors hitting the seabed, hauling gear over seabed, rubbing/entangling effects of ropes) can damage some species (Eno, MacDonald, & Amos, A study on the effects of fish (Crustacea/Molluscs) traps on benthic habitats and species., 1996). Other species appear to be resilient to individual fishing operations, but the effects of high fishing intensity are unknown (Eno, et al., 2001). Recovery will be slow (Foden, Rogers, & Jones, 2010) resulting in significant reduction or even loss of characteristic species. The individual impact of a single fishing operation may be slight but cumulative damage may be significant (Eno, et al., 2001)(Foden, Rogers, & Jones, 2010).

Through physical impacts from gear interacting with the seabed, line fishing activity has the potential to affect restoration of the reef to favourable condition, such that the extent and distribution of the qualifying habitat in the site; the structure and function of the qualifying habitat in the site; and the supporting processes on which the qualifying habitat relies are restored.

This evidence suggests impacts from interaction may occur from line fishing activity over the species associated with the reef habitat. When considering the low intensity of line fishing activity occurring within Wyville Thomson Ridge (Figure 3), it is not considered that this level of activity would have an adverse impact on site integrity.

Accordingly, Scottish Ministers conclude that demersal line fishing at current levels is compatible with the conservation objectives of the site, and will not result in an adverse effect on site integrity.

3.4 Part B Conclusion

The assessment of fishing pressures at current activity levels on the Annex I Reef Feature in Wyville Thomson Ridge SAC has indicated that an adverse effect on site integrity cannot be ruled out where mobile demersal trawling activities occur, and that there is no adverse effect to site integrity as a result of demersal line fishing. As such Scottish Ministers conclude that management measures to restrict mobile demersal gear would be required within Wyville Thomson Ridge SAC to ensure the integrity of the site. Scottish Ministers also conclude that it may be necessary to restrict static gear activity in areas where Vulnerable Marine Ecosystems are present due to the features sensitivity of this gear type. Section 5 contains further details on potential measures.

Contact

Email: marine_biodiversity@gov.scot

There is a problem

Thanks for your feedback