Early Adopter Communities: evaluability assessment

This report presents the findings of an evaluability assessment for the school age childcare Early Adopter Communities. This includes considerations and recommendations for process, impact, and economic evaluations.

5. Economic Evaluation

This chapter explores the requirements for completing an economic evaluation of the EACs with the principles of the HM Treasury Green and Magenta Books. This includes identifying what questions an economic evaluation should seek to address, as well as assessing different methods of economic evaluation.

Overall economic evaluability assessment

The evaluability assessment has considered the feasibility of undertaking different methods of economic evaluation for the programme. These include the 4Es (Economy, Efficiency, Effectiveness and Equity) approach to assessing value for money (VfM), Cost-Benefit Analysis (CBA), Cost-Effectiveness Analysis (CEA), or Breakeven analysis. The results of the evaluability assessment suggest that the National Audit Office’s 4Es approach to VfM (used interchangeably with “economic evaluation”) is the most appropriate method to use. This approach is also recommended by the Government’s Evaluation Taskforce, where intervention benefits are difficult to quantify. As a minimum, the evaluation would need to use familiar, established methodological approaches for assessing the economy (minimising spending on necessary inputs), efficiency (spending well), effectiveness (spending wisely), and equity (spending fairly) of the EACs.

Economic evaluation aims

A VfM assessment of the EACs would seek to understand how far the additional benefits (those produced as a result of the funding) exceed the costs involved. The assessment would assess the additional benefits created by the programme, i.e. compared to a counterfactual scenario of “no funding”. The outcome of the assessment provides an overall judgement of the extent to which the programme has delivered value for money while minimising risks for the public purse.

Economic evaluation methods

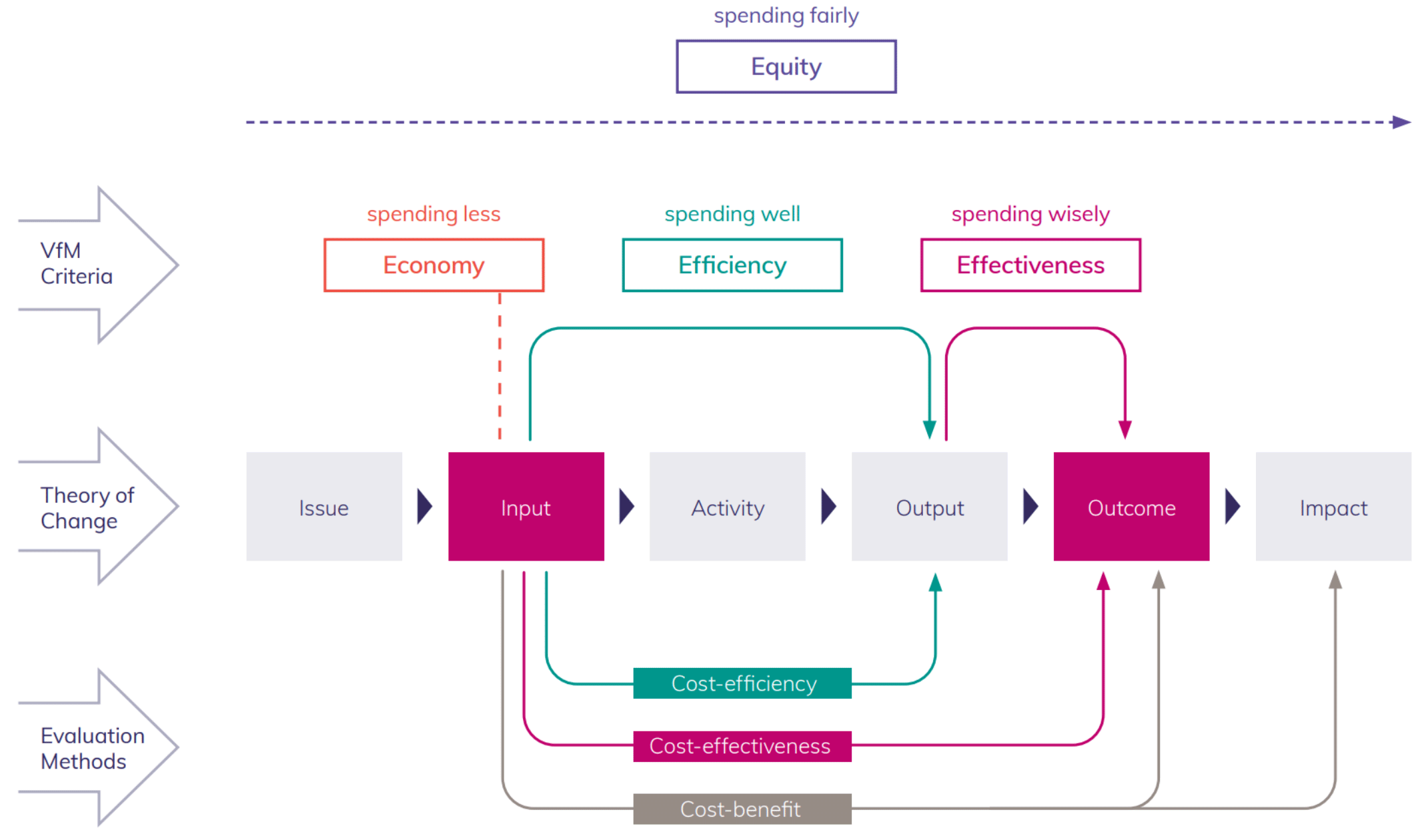

The evaluability assessment has considered the feasibility of undertaking the 4Es (Economy, Efficiency, Effectiveness and Equity). The 4Es approach is complemented by supplementary methods, including: Breakeven analysis, Cost-Benefit Analysis (CBA) and Cost-Effectiveness Analysis (CEA). Figure 5.1 below is a diagram which demonstrates how these different methods of economic evaluation interlink and can be mapped to each stage of the theory of change.

Source: Charted Institute of Public Finance and Accountancy (CIPFA), VfM Theory of Change, July 2021

The selection of an economic evaluation method largely depends on the information available (both qualitative and quantitative) to support an assessment and whether a counterfactual scenario can be established. This section provides an overview of the methods and summarises the benefits and challenges of each.

The 4Es framework

The National Audit Office (NAO) uses three criteria to assess VfM of government spending:

- Economy – the degree to which public spending on the EACs was the minimum required to achieve its objectives.

- Efficiency – the extent to which the outputs arising from the EACs were delivered efficiently (i.e. at minimum cost, using minimum resources, on the right things and at the right time).

- Effectiveness – how far the outputs arising from the EACs led to their intended outcomes and impacts, and the costs involved in producing these.

The NAO also suggests that, in some cases, a fourth “E” is applied:

- Equity – how fairly the benefits of the EACs are distributed.

The 4Es framework is viewed as a guiding framework to assess VfM, which can be complemented by supplementary methods.

Proposed economic evaluation questions

Under the 4Es framework, the key questions an economic evaluation should seek to answer are aligned to each “E” dimension. An indicative set of questions is listed below. These reflect both the local-level theory of change and those proposed within the impact evaluation to ensure coherence across the evaluation. Questions that are considered key are in bold. The questions would be informed by data collected through the process and impact evaluation and, where applicable, secondary data sources. It is important to determine the robustness of evidence collated by the underlying process and impact evaluation to determine the level of confidence in VfM assessments made.

| Dimension | Proposed questions | Supporting evidence |

|---|---|---|

| Economy – was the intervention delivered at the lowest cost possible to achieve its objectives? |

|

These questions would largely be answered using monitoring data (proposed cost breakdown data and childcare places) and through qualitative evidence gathered in interviews with professionals – staff involved in the delivery of EACs and wider stakeholders, including Scottish Government representatives. |

| Efficiency – how well are inputs converted into outputs? |

|

This would be answered using monitoring data and evidence gathered in interviews with professionals (staff involved in the delivery of EACs and wider stakeholders, including Scottish Government representatives). These questions should also be answered using the findings from the process evaluation. |

| Effectiveness – How well do those outputs convert into outcomes? |

|

Effectiveness questions would rely heavily on the evidence gathered from the impact evaluation. |

| Equity – how well do the activities, outputs and outcomes reach all people that they are intended to? |

|

These questions would be answered through the proposed longitudinal case studies with families providing insight into how they are using childcare support and how this has supported changes in employment and financial pressures. In addition, data from qualitative interviews with professionals would provide insight on this, particularly outcomes for family groups who may be challenging to recruit for longitudinal case studies. For example, some priority groups (such as families with a baby) have been less well represented among parents using EAC services and may be harder to reach. |

The assessment should also consider these issues in relation to how far there were alternative approaches that could have delivered better value for money. This will require:

- Internal comparisons – interventions using different mechanisms to deliver the same types of outcomes. The different types of childcare provision in the EACs include breakfast clubs, activity-based after school care, and holiday clubs. Some services are delivered by registered childcare providers or in schools, where other services are run by third sector organisations.

- External comparisons – between other initiatives known to have similar objectives, such as the ACF projects, the Child Poverty Pathfinders in Glasgow and Dundee, and other funded projects to provide after-school and holiday football clubs and summer programmes. It may also include divergent approaches, for example changes to the Scottish Child Payment or local employability schemes, which would have an impact on the beneficiaries of the programme in EAC areas.

In the absence of a quantitative impact evaluation, which would provide an estimate of the size and value of the impacts against a counterfactual scenario, the 4Es approach is appropriate. This is a guiding framework to assess VfM and may be complemented by supplementary methods (discussed further below).

Supplementary methods

Breakeven analysis

Breakeven analysis provides information on what change in outcomes would be necessary for the EAC’s benefits to meet costs. This analysis aligns with CEA in Green Book terms, i.e. it explores the unit cost of achieving a desired outcome. This enables arguments to be made for the EACs without the need for extensive assumptions and caveats that relate to CBA. Findings from the theory-based impact evaluation could be used to explore how the EACs have progressed towards identified breakeven points.

The level of investment allocated to the EACs can be compared to the monetary value of the benefits they can be expected to produce. An illustrative example of this is set out below:

| Desired outcome | Proposed Breakeven analysis | Data required |

|---|---|---|

| Parents/carers prepare for/ start/increase hours of work | How many people would need to enter the workforce or increase hours worked until the economic benefits reached the cost of implementing the EACs i.e. at what level they would be net positive in terms of value produced. |

|

| Improved parental wellbeing | How many parents/carers would need to report increased life satisfaction until the social benefits reached the cost of implementing the EACs at what level they would be net positive in terms of societal value produced. |

|

The application of Breakeven analysis would only be able to look at outcomes in the theory of change where there is secondary data to support the calculation. For example, a literature review would be required to determine whether there is an average estimate of social wellbeing gained through greater provision of childcare. This proxy measure could be applied to the number of parents accessing EACs support.

Cost-benefit analysis

Cost-benefit analysis (CBA) would place a monetary value on the impacts delivered by the EACs and would link these to the costs involved with their delivery. This would consider the value of the social and economic costs and benefits of the EACs and would primarily draw from the results of a quantitative impact evaluation. The value for money associated with the EACs would be judged through the benefit to cost ratio (i.e. the £s of benefits per £1 of economic cost). This metric could then be compared with other schemes to benchmark against other initiatives to help explore how far alternative courses of action could have delivered similar results more efficiently.

In line with HMT Green Book guidance, it would be necessary to focus on the net resource associated with the delivery of the EACs. The net resource costs would be derived from the following:

- Administrative costs – The resources consumed in the delivery of the EACs, including costs incurred by Scottish Government and local authorities, as well as other parties involved e.g. childcare providers. These costs would ideally be sourced by Scottish Government, Local Authorities or EACs. In the absence of recorded administrative cost data, estimates could be made based on the number of full-time employees.

- Costs of additional childcare consumed – The economic resources expended by childcare providers where they were stimulated to provide additional or new services. A quantitative impact evaluation would need to provide estimates of the additional levels of childcare provision (capacity and cost), which can be cross checked against monitoring data.

This approach necessarily assumes that the resources consumed by providers would have been deployed productively in the absence of the EACs.

The benefits of the EACs can be broadly broken down in terms of economic impacts and social benefits:

- Economic impacts: on the assumption that the EACs are effective in increasing or stimulating school-age childcare provision, enabling parents and carers to secure or increase employment, it would be expected to lead to an expansion of Gross Value Added and employment. These effects are likely to be:

- Direct effects – This is income and employment generated that occurs in the local areas where funding has been provided.

- Indirect effects – Income and employment generated in the chain of companies that supply products to those involved in the direct stage.

- Induced effects – This occurs as employees from the direct stage spend their wages and salaries in the economy (e.g., spending in the local economy, or spending in the wider economy).

The effects described above are largely on the demand side of the economy. Existing childcare services or provision of services that would have happened without the funding in the EAC areas would have been contributing to the direct, indirect, and induced impacts under a no intervention scenario. Therefore, what would have happened in the absence of the EACs must therefore be considered (“deadweight”). This is particularly true for Glasgow, where all services were existing prior to the funding, and Clackmannanshire, which had two existing registered services providing childcare.

The net economic benefit of the EACs is likely to be determined by the degree to which it improved overall economic efficiency. This would result from productivity gains by increasing the use of resources that would have otherwise been idle or under-utilised (e.g. parents worked fewer hours or were not in the labour market). This would require employment data such as labour supply (number of individuals entering employment) and hours worked to be collected by the EACs. This would allow an indicative assessment of the Gross Value Added.

- Social benefits: the theory of change also notes several positive social benefits of the EACs. For the purposes of the economic evaluation, the assessment should consider:

- Improvements in parental wellbeing – additional capacity and funded provision of childcare services is expected to increase families’ engagement with support services and improve parental respite, leading to improved parental mental health and wellbeing. The EACs also have embedded family support services and/or signpost parents as needed to other services.

- Improvements in children’s wellbeing – access to childcare services is expected to provide several benefits to children, including increased social connections, increased learning and new experiences, increased opportunities to be physically active, access to nutritious foods and improved social, emotional and behavioural development.

Several data sources have been explored to support an estimation of social benefits per service user including:

- Annual Population Survey – UK household survey providing information on important social and socio-economic variables at local levels.

- Manchester CBA Unit Cost data – a unit cost database covering thematic areas such as education and skills, employment and economy, housing, health and social services.

- Sport England Social Return on Investment model – youth sport participation research determining a ratio of 4:1 for every £1 spent on sport and physical activity.

- Child WELLBY – HM Treasury Green Book supplementary guidance on wellbeing was published in 2021 to provide practical advice on wellbeing appraisal. The “Wellbeing-adjusted Life Year” (WELLBY) is a one-point change in life satisfaction on a Likert scale between 0 to 10, for an individual for one year.

A CBA would usually also incorporate estimations of externalities of the intervention, i.e. the costs and benefits which have spilled over to third parties not directly affected by the EACs. This may include money saved through reduced pressures on healthcare systems because of improved wellbeing, increased physical health amongst children, and increased community value. It would be challenging to derive estimates of these without access to data on the consumption of social services and healthcare data.

Cost-effectiveness analysis

Cost Effectiveness Analysis (CEA) explores the unit cost of achieving the impacts or results in terms that can be compared to other similar initiatives. CEA requires fewer assumptions and is easier to implement than CBA as it does not require monetisation of benefits. Furthermore, CEA has been used successfully for programmes designed to improve children’s outcomes, where evaluations have used established, standardised measures that could be quantified. For example, the evaluation of the Sure Start programme applied CEA and estimated the cost of a unit of improvement in child behaviour resulting from a parenting programme (both compute an Incremental Cost Effectiveness Ratio (ICER)).

CEA measures costs in a common monetary value and effectiveness in terms of physical units. For EACs, this could take form of a partial CEA which would consider:

- The cost per additional childcare place. In this case the physical unit to measure effectiveness of place-based childcare (accessible to families who need it) is the number of additional children using the childcare service. Referring to the data sources set out in Chapter 3, this approach would use monitoring data to determine the number of childcare places taken up, and service cost data to determine the unit cost of providing an additional childcare place.

- The cost per additional person accessing employment. The unit of effectiveness here would be the number of parents securing employment, additional employment, or training. This would rely on the longitudinal case studies to provide estimates of the number of parents progressing into/along employment and accessing training opportunities.

It is important to note that one of the key limitations of CEA is that the results cannot always be directly compared with other interventions as they typically use different target groups, outcome measures and interventions, compared to the monetised benefits and costs within a CBA.

The results of the evaluability assessment highlighted two key challenges to implementing a CBA or CEA:

- A lack of information available to support a cost calculation. Service costs have been provided via a spreadsheet which sets out the funding allocations to each EAC and childcare provider. An economic evaluation would need clarity on the amounts spent by each provider and, preferably, a breakdown of implementation costs (administrative/programme costs).

- Inability to implement a quantitative impact evaluation. Economic evaluations should be informed by the evidence collected about additional benefits generated by the intervention as part of the impact evaluation, and by evidence about the extent to which the EACs have achieved their objectives as part of the process evaluation. As highlighted in Chapter 3, a comprehensive quantitative impact evaluation could only plausibly be implemented if the scale of the EACs increased to achieve sufficiently large sample sizes, if data sharing arrangements can be secured for accessing individual-level secondary data (e.g. on employment), and if an appropriate counterfactual group can be identified. Furthermore, establishing the true opportunity cost of the funding is challenging when it is unclear what the alternative use of the funding would have been.

Summary of economic evaluation methods

A summary of the economic evaluation approaches explored for this evaluability assessment has been included below.

| Approach | Description | Challenges and limitations | Assessment |

|---|---|---|---|

| 4Es approach |

|

|

Recommended. Suitable for both short-term and long-term evaluation. |

| Breakeven analysis |

|

|

Recommended as supplementary analysis to the 4Es approach. |

| Cost-benefit analysis |

|

|

Discounted due to lack of information available and discounted Quasi-experimental (QED impact design. |

| Cost-effectiveness analysis |

|

|

Discounted due to lack of detailed cost information available and comparator initiatives to contextualise findings. |

Contact

Email: socialresearch@gov.scot

There is a problem

Thanks for your feedback