Economic inactivity in Scotland: supporting those with longer-term health conditions and disabilities to remain economically active

This report examines the evidence on supporting those with longer-term conditions and disabilities to remain in work. Its focus is on the upstream prevention of economic inactivity to ensure the protective factors for health that good work provides.

Introduction

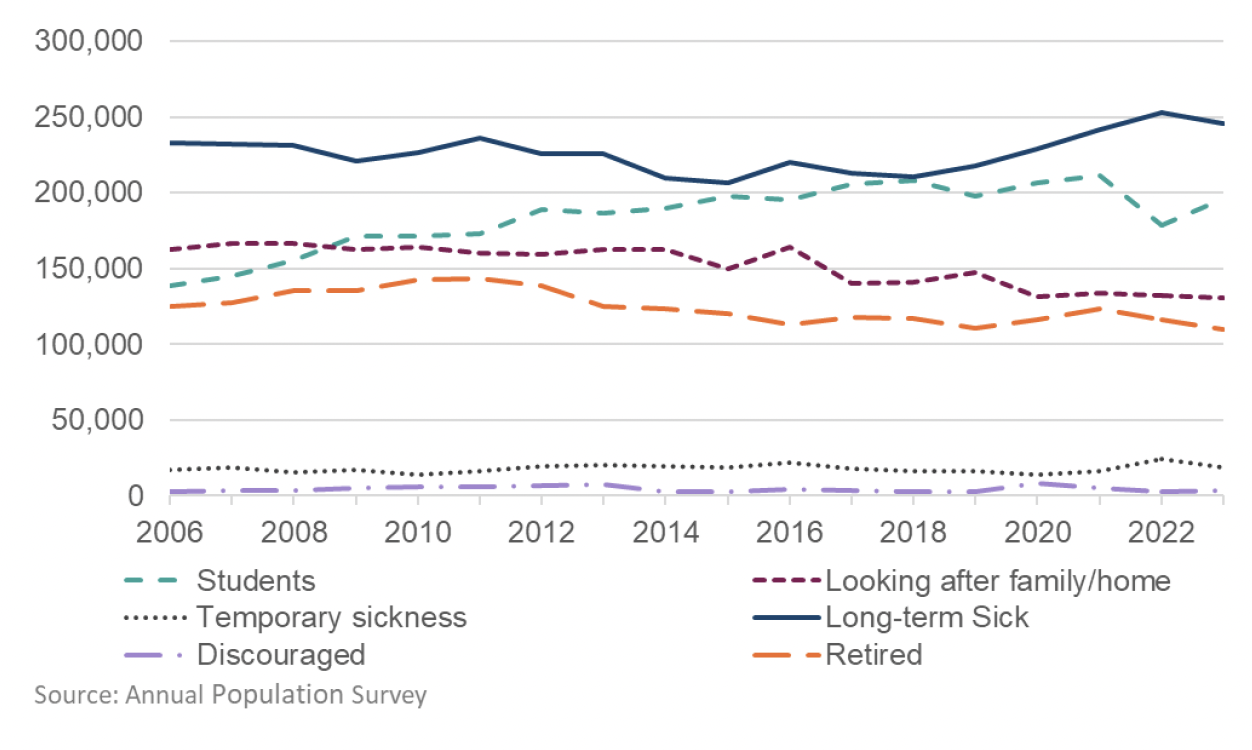

Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, rates of economic inactivity (ages 16-64) across the UK were at an historic low.[16] Since then the rate of economic inactivity has been increasing. Recently published data finds that, ‘between 2019 and 2022 (in Quarter 3, July to September) the number of economically inactive people aged 16-64 in the UK increased by almost half a million, from 8.6 to 9.0 million (seasonally adjusted)’.[17] The increase stemmed from both the youngest and oldest working age people. This trend puts the UK at odds with the majority of other OECD countries – one fifth of OECD economies still have a higher inactivity rate than pre-pandemic.[18] At Scotland-specific level, recent estimates from the ONS Labour Force Survey suggest that the economic inactivity rate (ages 16-64) was 23.1% for the period April to June 2024, 0.1 percentage points down from the same quarter the year before.[19] Long-term sickness is also the leading reason for inactivity (Figure 1).[20]

Analysis by the Institute for Public Policy Research (IPPR)[21] finds that the onset of a long-term health condition increased the likelihood of exit from the labour market by around 50% pre-pandemic and 53% during the pandemic. When that condition was a mental health condition likelihood of exit was increased to 71% pre-pandemic and 112% during the pandemic. This was seen across all income levels and age groups, though the likelihood increased further as age increased. However, there has also been a recent steep increase in younger adults becoming economically inactive, which is also a cause for concern. IPPR found health shocks generally decrease our ability to flourish at work, to remain productive, and to progress.

Recent evidence from the Resolution Foundation finds that the trend of becoming older and being more likely to be out of work due to ill health is no longer the case. Compared with 1998, younger workers in the UK (in their twenties) are now more likely to be economically inactive due to ill-health than workers in their forties – older workers are now actually less likely to be economically inactive due to ill health than they were in 1998.[22] Between 2012 and 2019, two-thirds of those young people were economically inactive due to a mental health condition.[23] This suggests there may be a need to tackle this issue from a range of angles, given there may be different policy responses required to tackle the experiences of different groups.

‘Economic inactivity’ is a complex category, made up of individuals who have retired, who are in full-time education, who have caring responsibilities, or who are experiencing long-term ill-health or disability. Much of the recent upturn in economic inactivity in the UK appears to be driven by long-term ill health and disability and it is this category of economic inactivity this paper will focus on. Scotland has a higher percentage of the population describing themselves as long-term unwell or disabled than the UK as a whole[24] and therefore may have specific health and policy challenges to tackle to encourage and support individuals to remain in the workplace.

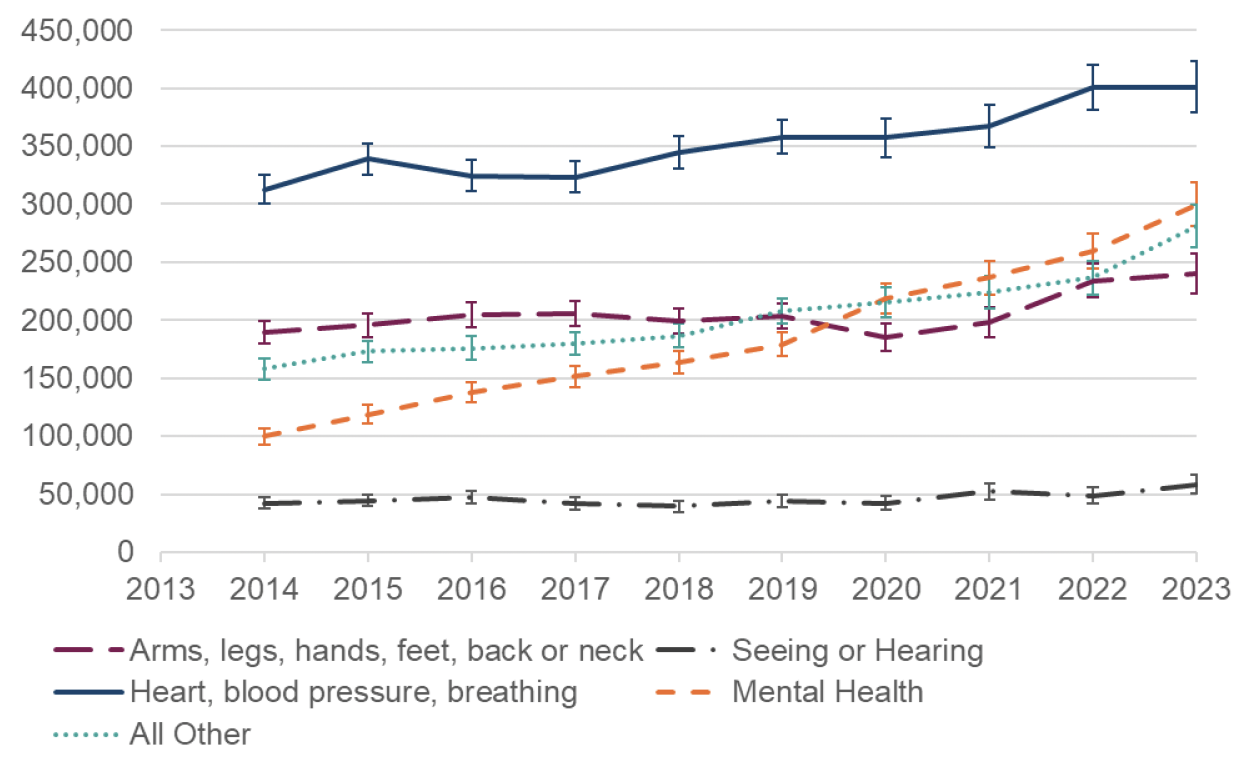

This may in part be due to an aging population. The rise in people reporting heart, blood pressure or breathing difficulties means it remains the most prevalent category of condition for those in employment. There has been a rapid rise in people reporting mental health conditions, rising from 100,000 in 2014 to 300,000 in 2023.

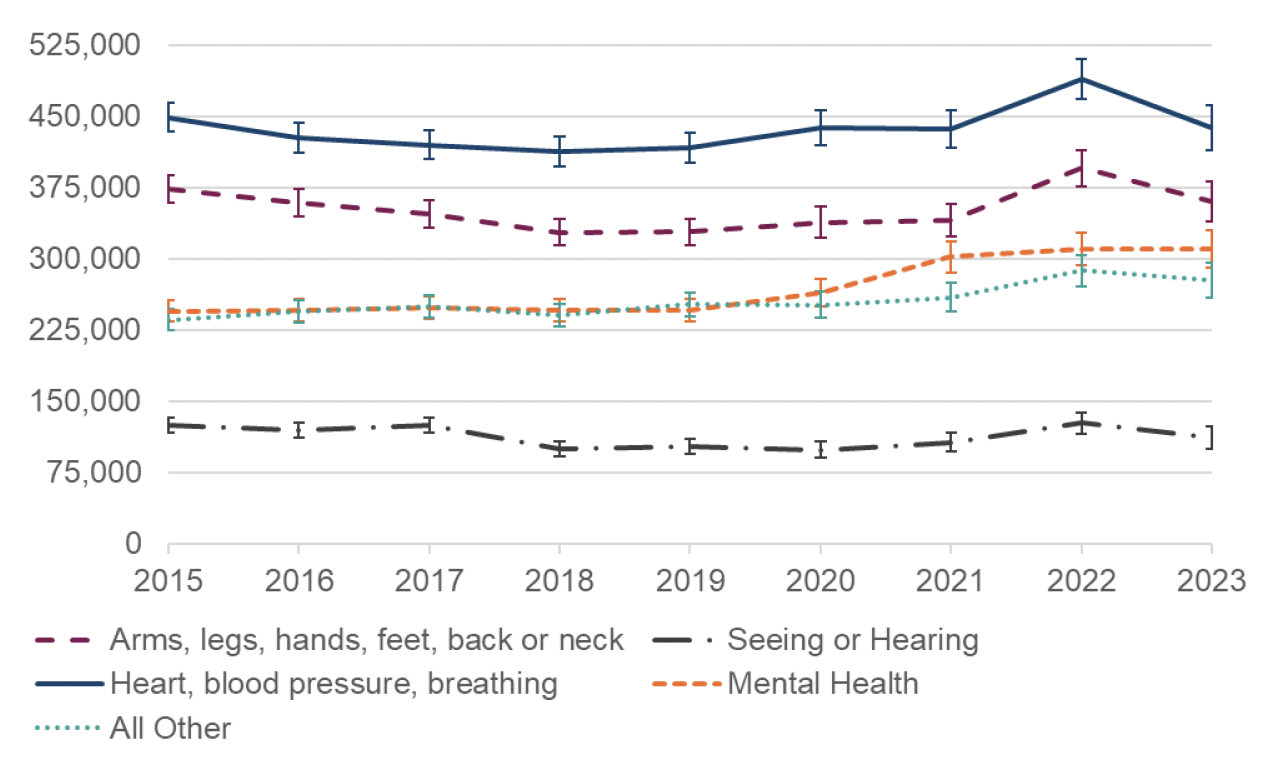

For those economically inactive, the Annual Population Survey gives insights on all people over 16, which includes those who are retired (Figure 3). Heart, blood pressure and breathing conditions remain the most prevalent in 2023. Conditions connected to problems with limbs, back or neck are next most prevalent and likely includes musculoskeletal conditions. The rise of mental health conditions among the economically inactive is also notable since 2020.

This evidence review is focused on upstream prevention, where those who are disabled or experiencing ill health could be supported to remain at work and stay economically active. There is good evidence that work offers protective health benefits.[25] These protective elements of work are what make it significant to supporting the health and wellbeing of those who experience chronic illness and disability, while also continuing to promote and sustain a healthy economy. The research questions that guide this work (see below) recognise that much of these protective elements of work require ‘good’ employment and that there is a potential for work to be detrimental to health if good quality work is not possible or sustainable. This work to reduce economic inactivity and to create good, supportive work environments is for government, the wider public sector, the third sector, and employers to engage in.

One important point is that the impact of Long Covid on economic inactivity rates is unclear – the complexity of categorising a condition as Long Covid and the fact it often comes under ‘Other’ in health and employment surveys mean clear data is limited.[26] However, given the UK saw similarly high infection rates during the Covid-19 pandemic as other countries that are now not experiencing the same rates of economic inactivity, the evidence base overall assumes that Long Covid is not a key driver here.[27] Long Covid is therefore not explored as part of this review. However, please note the Scottish Government has recently published a report Investigating the prevalence of Long Covid in Scotland.

The next sections of this paper go through the research questions underpinning the review, the research design and a high level description of the resulting evidence base, before turning to the key findings, and conclusions.

Contact

Email: socialresearch@gov.scot

There is a problem

Thanks for your feedback