Economic inactivity of young people aged 16-24: Definition, reasons and potential future focus

Report brings together evidence on inactivity and build knowledge on the reasons for inactivity amongst young people aged 16 to 24. In this report, we used published ONS data and have summarised the main results from existing published qualitative research for Scotland and the UK in the last 5 years

Reasons for economic inactivity

Data available on reasons for economic inactivity

Young people 16-24 can report different reasons for being economically inactive. In 2022, the majority of economically inactive young people self-reported being students (74.0%). The proportion of economically inactive people in full-time education aged 16 to 24 has decreased from 80.2% in 2017 to 75.1% in 2022.

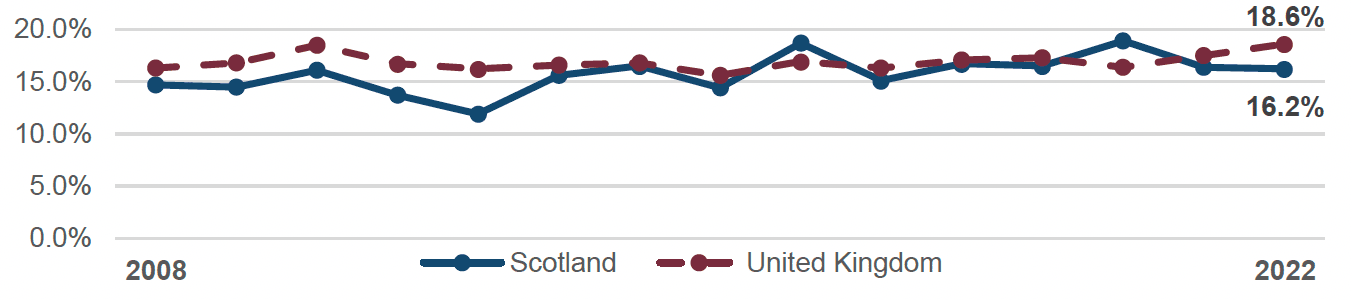

Similar to the data presented for unemployment rates, it is of relevance to explore rates and reasons of inactivity of young people that are not enrolled in full-time education. According to the latest data, the rate of inactivity of young people 16-24 not in full-time education for Scotland was of 16.2%. This was lower than the United Kingdom rate of 18.6% (Figure 8).

Source: Annual Population Survey. Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, data between 2020 and 2021 should be interpreted with caution. Data corresponds to time from January to December in any given year.

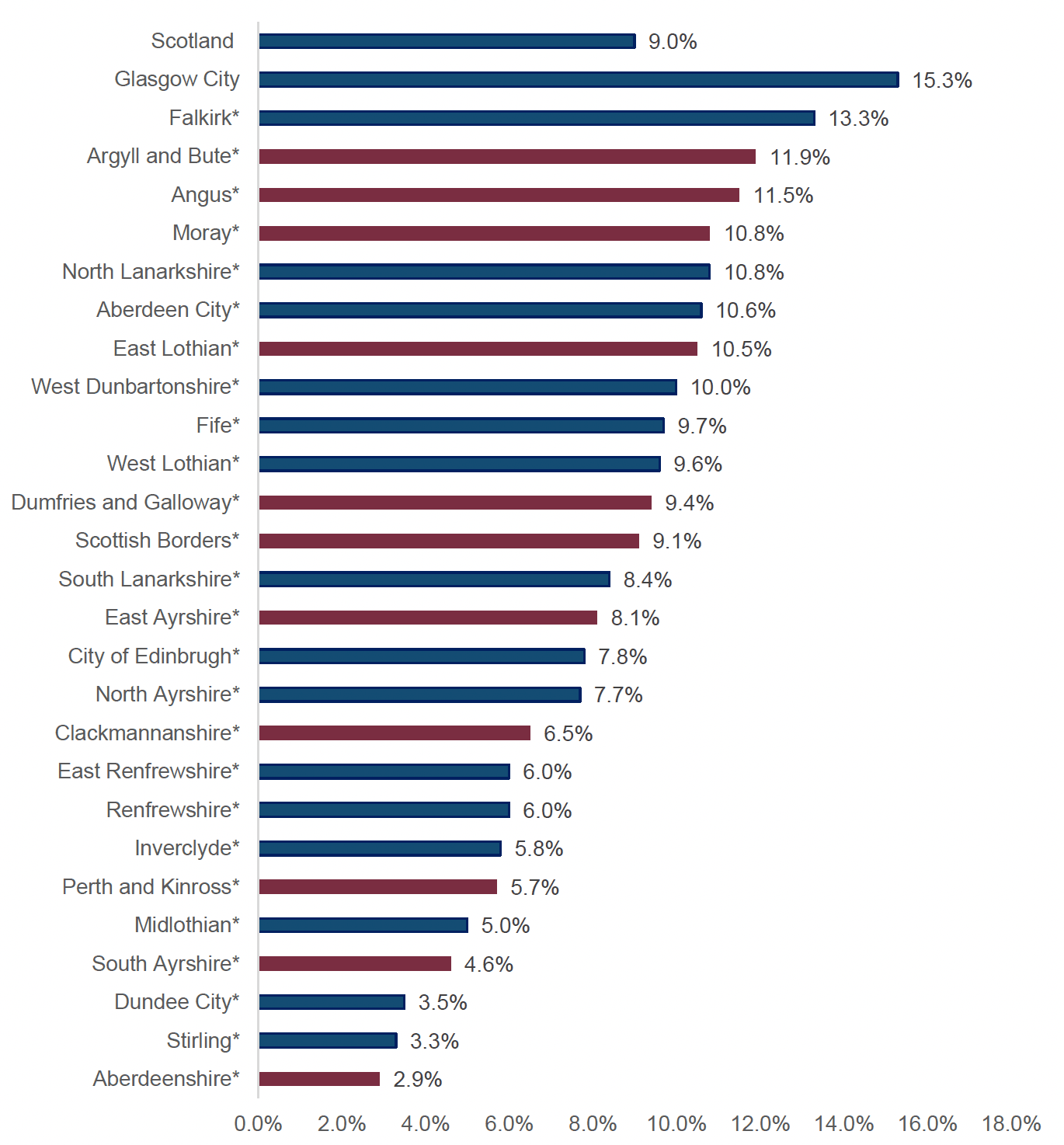

Figure 9 shows a breakdown of young people 16 to 24 who are inactive and not enrolled in education by local authority from 3-year pooled data in January 2018 to December 2020. Most of the estimates provided in the figure below are based on small sample sizes and should be used and interpreted with caution due to small numbers. Overall, the data shows that the proportions range between 2.9% and 15.3%, with 14 local authorities having a lower proportion of young people who are inactive and not enrolled in education when comparing to the overall figure for Scotland (9.0%).

Using the Rural and Environmental Science and Analytical Services (RESAS) categorisation, 11 local authorities are highlighted in burgundy in the figure below representing “mainly rural” or “islands and remote rural” local authorities. RESAS proposes the use of 15 local authorities. However, due to low sample size for 4 local authorities in this group, it is not possible to provide estimates for all 15 local authorities. East Dunbartonshire, Highland, Na h-Eileanan Siar, Orkney Islands, and Shetland Islands estimates are not included in Figure 9.

Five of the rural local authorities had values below the Scottish estimate, and these ranged from 8.1% to 2.9%. The other 6, reported estimates above the Scottish estimate of 9.0%. Argyll and Bute, Angus, Moray and East Lothian reported the higher proportions (11.9%, 11.5%, 10.8%, and 10.5%). The two local authorities with the highest proportion of young people who are inactive and not enrolled in education were Falkirk (13.3%) and Glasgow City (15.3%). The estimates for Argyll and Bute, Angus, Moray, East Lothian, and Falkirk are from small sample sizes and should be used with caution. Later in this paper, through the use of qualitative research, there are references to the role that location and access to job opportunities can have in young people’s experiences within the labour market. This could help explain the levels of inactivity in some of the rural areas depicted here.

Source: Labour Market team dashboard, Annual Population Survey. Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, 2020 data should be interpreted with caution. All proportions based on total 16 to 24 cohort.

*Indicates estimates should be used with some caution and are based on a smaller sample sizes.

Bars in burgundy refers to local authorities with data available and that are categorised by the Rural and Environmental Science and Analytical Services (RESAS) as “mainly rural” or “islands and remote rural”.

It is not possible to provide estimates due to very small groups for 4 local authorities: East Dunbartonshire, Highland, Na h-Eileanan Siar, Orkney Islands, and Shetland Islands.

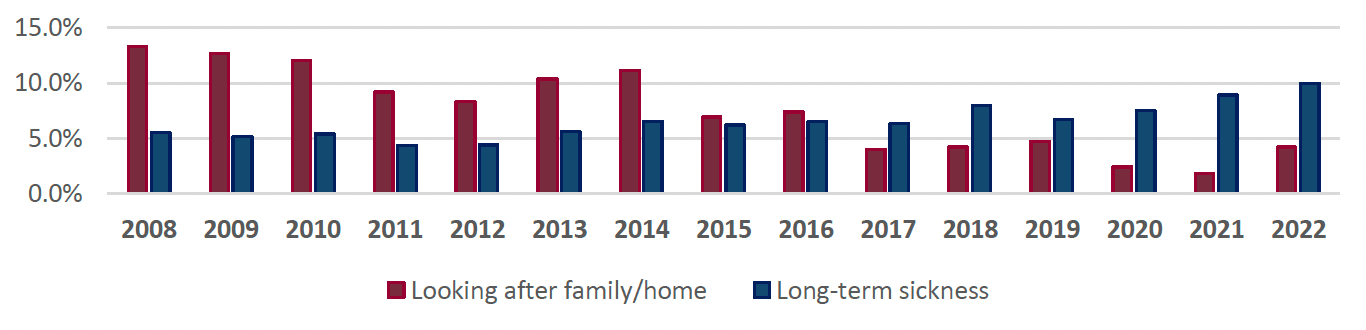

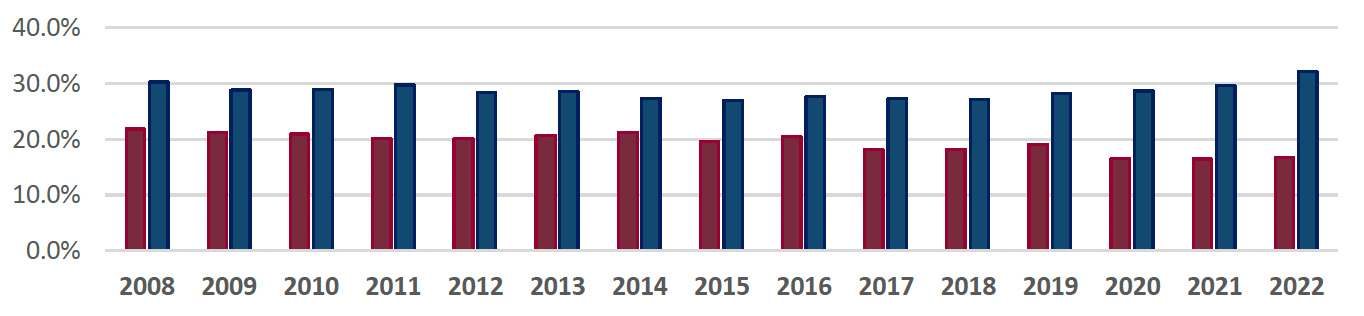

In the Annual Population Survey (APS), the inactive sample reports reasons such as caring responsibilities, sickness (temporary or long-term), feeling discouraged (i.e. believing there are no jobs available), and other (i.e. no reason, waiting for results of a job application). Figure 10 shows a change over time in the main reason for inactivity in the 16-24 cohort (Figure 10a) - from caring responsibilities to, more recently, long-term sickness. When looking at the 16-64 cohort, the reasons for inactivity remained relatively stable throughout the years (Figure 10b).

The latest data for 16-24 year olds shows that the highest level of inactivity is attributed to long-term sickness (10.0%). Comparing this data with the 16-64 inactive adults, long-term sickness has been consistently reported as one of the main reasons for inactivity. There was an increase in economically inactive 16-24 year olds reporting long-term sickness between 2020 and 2022 (2.5 pp) and between 2021 and 2022 (1.1 pp).

Caring responsibilities as a reason for inactivity for the 16-24 cohort increased 1.7* pp between 2020 and 2022. Latest data shows that, 16.7% of inactive adults 16-64 reported caring responsibilities as the reason for their inactivity. This is an increase of 0.4 pp and 0.3 pp in when comparing to 2021 and 2020 respectively.

* Estimates come from a small sample size and may be less precise. They should be used with caution.

Figure 10:

a) Percentage young people 16-24 economically inactive by reason: looking after family/home and long-term sickness.

b) Percentage of adults 16-64 economically inactive by reason: looking after family/home and long-term sickness.

Source: Annual Population Survey. Data corresponds to time from January to December. Data in the figures excludes student, discouraged, retired, and other as reasons for inactivity. Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, data between 2020 and 2021 should be interpreted with caution. Estimates for inactive 16 to 24 year olds in 2020, 2021, and 2022 who gave their reason as looking after family/home come from a small sample size may be less precise. These estimates should be used with caution.

It is of interest to explore the level of young people that despite being economically inactive want to secure employment in the future. Table 8 shows that although between 2018 and 2022 figures stayed relatively stable, between 2020 and 2021 there was an increase in 16-24 years old reporting not wanting to work and a decrease of young people wanting to work. One possible explanation could be the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic. The experiences of young people during the pandemic could have influenced their perceptions of their ability to secure a job reducing aspirations about their future.

| 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Want a job | 20.7% | 19.1% | 26.1% | 15.7% | 21.3% |

| Do not want a job | 79.3% | 80.9% | 73.9% | 84.3% | 78.7% |

Source: Annual Population Survey. Data corresponds to time from January to December. Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, data between 2020 and 2021 should be interpreted with caution.

For young people that want a job and report experiencing long-term sickness there was a decrease of 0.1* pp between 2018 and 2021 (2.8%* versus 2.7%*) (Table 9a). For young people that did not want a job (Table 9b), there was an increase of reporting long-term sickness as a reason for being economically inactive between 2018 and 2022 (5.3% versus 7.8%). Caring responsibilities increased from 3.0% to 3.3%* between 2018 and 2022.

* Estimates come from a small sample size and may be less precise. They should be used with caution.

| a) Percentage of young people 16-24 economically inactive by reason and by wanting a job, Scotland. | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 | |

| Looking after family/ home | 1.3%* | 1.4%* | - | - | - |

| Long-term sick | 2.8%* | 1.8%* | - | 2.7%* | - |

| Other | 2.9% | 4.0% | 7.6% | 3.0%* | 4.1%* |

| b) Percentage of young people 16-24 economically inactive by reason and by not wanting a job, Scotland. | |||||

| 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 | |

| Looking after family/ home | 3.0% | 3.4% | - | - | 3.3%* |

| Long-term sick | 5.3% | 4.9% | 6.2% | 6.2% | 7.8% |

| Other | 3.4% | 4.9% | 3.5%* | 7.1% | 5.2% |

Source: Annual Population Survey. Data corresponds to time from January to December. Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, data between 2020 and 2021 should be interpreted with caution. Some estimates were redacted due to not meeting the publication standards following robustness tests.

* Estimates come from a small sample size and may be less precise. They should be used with caution.

Reasons based on other evidence

The following section explores the details of a high-level desk-based review of the most recently published literature on inactivity amongst young people aged 16-24 in Scotland and the UK. This included searches for grey literature, published academic papers in journals and other sources of published evidence available in the last five years. This section provides insights into the evidence for both UK-wide and Scotland specific publications.

United Kingdom context

In addition to the reasons for being economically inactive provided by the Annual Participation Survey, other sources of published evidence give detailed information on a wider range of reasons. At a UK-level, evidence from the Understanding Society study offers further information on the reasons and risk factors relevant to economic inactivity. This study covers working age men and women in the UK, not including individuals in full-time education.

A recent Resolution Foundation report (2022) used the Understanding Society data and concluded that between 2012 and 2019:

- Two-thirds of 18-29 year olds who are economically inactive due to illness or disability, also reported poorer mental health. 65% reported being inactive and sick or disabled.

- Among young people 18-29 who are economically inactive those who experience a mental health disorder remain out of work for longer when compared with young people without a mental health disorder.

- 32% reported being inactive due to caring responsibilities (family or home care).

The Resolution Foundation report also showed a decline in economic inactivity due to family caring reasons in young people between the ages of 18 to 24. The authors offer some possible explanations for this decrease and note the increase in participation in the labour market by young mothers, as well as the drop in birth rates among young women. Additionally, the report also highlights that health-related problems as a reason for inactivity have been rising for both men and women within the UK. Finally, between 2017 and 2019, over three quarters of 18-29 year olds who were inactive due to long term sickness or disability had been workless for at least 2 years.

Similar to what was presented previously in this report, the Resolution Foundation (2023) used ONS data to explore the prevalence of youth (18 to 24 years old) worklessness due to ill health in different parts of the UK. They concluded that there are significant location differences – mostly in England. Youth worklessness variation between most and least deprived areas was small. In addition, this report highlights the significant role that mental ill health plays in youth worklessness, suggesting that there should be investment in interventions to support young people’s mental health.

A report by the Learning and Work Institute (2022) highlighted the challenges that NEET young people face when finding a job. In this study, mental illness was the most common barrier to employment for young people. Reasons such as long-term health problems or disabilities were also reported by participants. In addition to health reasons, participants also reported other factors such as a lack of confidence in their skills, not enough opportunities for work experience and difficulties with the application or interview processes. Young people in this report also mentioned childcare responsibilities as a barrier to employment.

Holmes et al. (2021) explored the changes in NEET in young people 16-29 in the UK between 1975 and 2015. The authors explored some of the possible risk factors and reasons for young people in this age group falling within NEET. They proposed 5 key risk factors:

- Low qualification level. This was mainly reported for females where there is a higher propensity to start a family before the age of 30, meaning that they are more likely to drop out of school or not continue education into Higher Education once they had children.

- Older aged young people. The authors concluded that there was a higher likelihood of older young people (19-22 years old) becoming NEET.

- Having children and age. Young people under 22 years old and those who have children were more likely to become NEET by 58 percentage points.

- Mental illness. The authors reported that existence of mental illness was associated with a high risk of being NEET for both females and males (with these effects being higher for mental illness when compared with other physical health concerns).

One interesting finding from Holmes et al. (2021) was that completing a trade apprenticeship was linked with a higher probability of being NEET, with this risk factor being higher for females. It is interesting to explore these findings in light of young people possibly being enrolled in trade apprenticeships and not able to find work after completion. However the information about this relationship is scarce.

In addition, a NFER (2023) report explored providers views on the barriers young people face when accessing intermediate and advanced apprenticeships. Following roundtable discussions with providers, the authors concluded that there was a lack of understanding from young people on the possible progression opportunities, there were issues in demonstrating the necessary skills and qualifications, as well as young people struggling with the application process and young people not demonstrating the necessary skills to enter the job market.

Danner et al. (2022) conducted 57 in-depth interviews to explore the reasons for economic inactivity amongst young women (16-25 years old) in the UK. Maguire (2018) has also explored reasons for economic inactivity and drew from research conducted in England with young women. The data from both these studies revealed that barriers such as motherhood and other caring responsibilities can have a significant impact on young women’s transitions between education and the labour market. Reporting experiences of mental illness (e.g., depression and anxiety) were also shown to have a significant impact on economic inactivity. Living in a disadvantaged location (e.g., rural areas), being from a lower socioeconomic background, as well as their living situation (e.g., the need to live close to family on who they depend economically and emotionally) have also been reported by young women as a key barrier for their involvement within the labour market. Finally, the authors also highlight that participants report a low level of opportunities within their geographical area, which hinders their capability to become economically active.

Related to more social and emotional components, participants in these studies also reported struggling with their self-esteem and self-confidence in returning to the labour market following motherhood, the challenges of securing financial support for childcare, and isolation from social networks.

Scottish context

In 2015, the Scottish Government published a report “Consequences, risk factors and geography of young people not in education, employment or training (NEET)”. This report uses census data and shows that there were different risk factors influencing young people’s levels of inactivity, though most of these were similar for both males and females.

- Level of qualification was shown to influence levels of inactivity amongst young people. Young people with no qualifications had an increased risk of being NEET - ten times higher for males and seven times higher for females in 2011.

- School experiences and behaviours: absenteeism, exclusions, and registration for free school meals have been reported to also increase the likelihood of economic inactivity.

- Teenage pregnancy (though in a small proportion). This has been shown to be associated with a risk of being ten times more likely of being economically inactive.

- Unpaid carer. This factor was mostly associated with females.

- Household elements: housing (i.e. renting instead of owning a residence) and location (e.g. living in deprived and urban areas) have also been reported to play a role in inactivity.

- Family structure - like the number of siblings, unemployed adults living in the home - have significant impact in increasing levels of inactivity in young people.

A more recent report from the Glasgow Centre for Population Health (2022) proposed factors that can act as barriers or supporters of young people’s transitions into adulthood. Interviews and focus groups with 31 young people aged 16-20 in Glasgow showed that some of the challenges experienced by the participants in this study were:

- Mental illness: affected participant’s ability to transition into adulthood by blocking the achievement of qualifications.

- Poverty: the financial pressures of attending job interviews due to the lack of funds to travel to the place of the interview or to buy adequate clothes for the interview.

- Knowledge of schemes: participants in this study reported not being aware of existing government and local schemes to help young people.

- Support and availability of resources/support: the report highlights participant’s experiences of having an existing support system in place (such as family, friends or school-staff) to aid in decisions related to their future.

Peer-reviewed papers using a qualitative methodology have been published exploring the reasons and risk factors associated with young people’s economic inactivity in Scotland. McPherson (2021) used discourse analysis to explore and evaluate policy rhetoric in the UK and Scotland regarding economic inactivity of young people. Additionally, the author also analysed qualitative data collected with 42 economically marginalised young people (14 to 29 years old) from two contrasting areas of Scotland, an urban city and a small semi-rural town.

McPherson (2021) concluded that young people reported a lack of support and information when it comes to transitions into the job market. Participants in this research also reported that often the focus is on improving what they called “work ethic and attitude”. Further to this, young people from disadvantaged backgrounds felt that the way the rhetoric around policy is presented places the emphasis on the young person being responsible for their experiences with the labour market, with some participants reporting feeling “blamed” for the position they are in.

This research focused on two deprived areas in Scotland and the participants highlighted the impact that their background and social class has on the ability to engage with the labour market. For example, some participants reported feelings of shame and stigmatising attitudes from the educational staff around them, as well as from potential employers. Young people in this research mentioned feeling discrimination when transitioning between education and the job market. Additionally, participants discussed the role that lack of financial means, troubled home life and low social capital have in identifying opportunities and accessing the job market.

Finally, McPherson (2021) highlighted barriers such as age and perceptions of not being experienced enough to apply for a particular job. Participants reported discrimination when it comes to older candidates being preferred to younger candidates due to the risk associated with investing in a younger and less experienced candidate.

Contact

Email: socialresearch@gov.scot

There is a problem

Thanks for your feedback