New Scots Refugee Integration Strategy 2018 to 2022: evaluation

Findings from an independent evaluation of the New Scots Refugee Integration Strategy 2018-2022. The evaluation draws on quantitative and qualitative research with stakeholder organisations, refugees & people seeking asylum in order to understand the impacts of the strategy.

3. Findings

This chapter outlines the findings from all elements of the evaluation thematically. The first section (3.1) focuses on participants’ experiences and views of the development of the 2018-2022 New Scots Refugee Integration Strategy. Participants’ awareness, understanding and perceived relevance of the Strategy to their own work is discussed next (3.2). Participants’ experiences of using the Strategy and their views on factors that helped and hindered implementation of the Strategy follow (3.3) before progress towards meeting the Strategy outcomes is discussed (3.4). The chapter concludes with a look at what learning can be drawn from the implementation of the 2018-2022 New Scots Refugee Integration Strategy to inform the development and implementation of the next iteration of the Strategy.

3.1. Developing the New Scots Refugee Integration Strategy

Drawing data from the stakeholder survey and stakeholder interviews, this section addresses the following research questions:

- Has the intended reach [of the New Scots Refugee Integration Strategy] been achieved?

- How have the outcomes of New Scots [Refugee Integration Strategy] benefited from the partnership approach to policy and implementation?

About half of the stakeholders who were interviewed reported that they had been involved in some way in the development of the first New Scots Refugee Integration Strategy, the second iteration of the Strategy or both. It should also be noted that a few respondents who said that they had not been involved in Strategy development indicated that predecessors in their organisations did play a role.

The stakeholders stated that they had been involved in the development of the Strategy in a range of ways. Those who had been most actively engaged reported involvement in the development and drafting of one or both iterations of the Strategy, chairing groups that fed into the Strategy as well as leading or taking part in conferences, seminars and engagement sessions that also informed its development. Other ways in which stakeholders were involved included offering feedback to a thematic group or at an engagement session, and ascertaining the views of those with lived experience to ensure that refugees and people seeking asylum themselves informed Strategy development. Stakeholders were also involved in other work, such as the development of an ESOL Strategy.

Stakeholders’ views around the extent to which voices of refugees and people seeking asylum had been captured in the development of the Strategy were mixed. Some argued that the voices of refugees and people seeking asylum were missing from the Strategy. Others felt that the Strategy (particularly the engagement process in its early days) had allowed refugees and people seeking asylum to feel listened to and empowered.

One common theme expressed, especially by those with more active involvement in the Strategy, was that the development of both iterations of the New Scots Refugee Integration Strategy relied very much on the goodwill of stakeholder organisations with very little, if any, funding available to support the process of Strategy development. Individuals would have liked to have had their time and expenses paid for, to ensure that Strategy development activities could be acknowledged as integral to their work, rather than something organisations had to self-fund to be part of.

“One of the things about New Scots 1 and New Scots 2 is it has been done on an absolute shoestring and is entirely based on voluntary work. The only people with paid time to work with this are the two civil servants in Scottish Government. Everybody else was doing this, it's in the interests of their organisations to be able to put some of their staff time into it, but right down to paying expenses to get to meetings, you pay it out of your personal pocket, or you ask your employer if you can claim.” (Stakeholder interviewee)

3.2. Awareness and understanding of the New Scots Refugee Integration Strategy

The following section includes data from the stakeholder survey and interviews, and applies to the following research questions:

- Has the intended reach [of the New Scots Refugee Integration Strategy] been achieved?

- How have the outcomes of New Scots benefited from the partnership approach to policy and implementation?

This section covers participants’ awareness and understanding of the New Scots Refugee Integration Strategy. Drawing on data from both the stakeholder survey and interviews with stakeholder organisations, it explores how participants became aware of the Strategy and their views of what the Strategy aimed to achieve.

3.2.1. Awareness of the New Scots Refugee Integration Strategy

The online survey asked stakeholders about their awareness of the Strategy (see Table 3.1). The majority of respondents reported that they were aware of the Strategy or had used it in some way. More than a third (37%) could be said to have high awareness of the Strategy, having either helped develop it (10%) or frequently referred to it (27%). Almost half (47%) had medium awareness and said they had read at least some of the Strategy. In contrast, 15% could be said to have low awareness, stating that they knew the Strategy existed but had not read it (11%) or that they were not aware of it (5%).

| N | % | |

|---|---|---|

| High awareness of the Strategy | ||

| I helped to develop the Strategy | 25 | 10.0 |

| I frequently refer to the Strategy | 67 | 26.8 |

| Medium awareness of the Strategy | ||

| I have read at least some of the Strategy | 118 | 47.2 |

| Low awareness of the Strategy | ||

| I know the Strategy exists but I haven’t read it | 28 | 11.2 |

| I am not aware of the Strategy | 12 | 4.8 |

| Total | 250 | 100 |

Analysis found little correlation between respondents’ type of organisation and their levels of awareness.

The stakeholder interviewees reported varying levels of awareness of the content of the second New Scots Refugee Integration Strategy. This is not surprising in that those interviewed included those who had had a role in developing the second Strategy (and indeed its first iteration), those who were members of the thematic groups, as well as those who had drawn on aspects of the Strategy only, for example, when making a funding application. Similarly, when asked how well known the New Scots Refugee Integration Strategy was more widely, the consensus was that those who worked in the relevant governmental and policy circles were aware of it, whereas organisations with a specific interest (e.g., language) might be aware only of elements relevant to that issue. It was also perceived that those working on smaller-scale initiatives, refugees and people seeking asylum and the general public would have little if any knowledge and awareness of the Strategy, but that arguably this was not important as long as initiatives and work with refugees reflected its broad aims.

“I think the people working in the field are aware of the Strategy and are aware of the term New Scots, I don’t think it’s a commonly understood phrase in the general public.” (Stakeholder interviewee)

3.2.2. Relevance of the New Scots Refugee Integration Strategy

Survey participants were asked about the relevance of each of the four outcomes which the Strategy sets out to achieve to the work of their organisation. The four Strategy outcomes were:

1. Refugees and asylum seekers live in safe, welcoming and cohesive communities and are able to build diverse relationships and connections.

2. Refugees and asylum seekers understand their rights, responsibilities and entitlements and are able to exercise them to pursue full and independent lives.

3. Refugees and asylum seekers are able to access well-coordinated services, which recognise and meet their rights and needs.

4. Policy, strategic planning and legislation, which have an impact on refugees and asylum seekers, are informed by their rights, needs and aspiration

The majority of respondents reported that each of the four outcomes was ‘very relevant’ or ‘quite relevant’, but the proportions varied by outcome (see Table 3.2). More than 90% of respondents said Outcomes 1, 2 and 3 were ‘very’ or ‘quite relevant’. Although 85% said Outcome 4 was at least ‘quite relevant’, 11% of respondents thought that it was not very or not at all relevant to the work of their organisation.

| Very relevant | Quite relevant | Not very relevant | Not at all relevant | Don’t know/ NA | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | |

| Outcome 1: ‘Refugees and asylum seekers live in safe, welcoming and cohesive communities and are able to build diverse relationships and connections’ | 199 | 84.7 | 25 | 10.6 | 3 | 1.3 | 2 | 0.9 | 6 | 2.5 |

| Outcome 2: ‘Refugees and asylum seekers understand their rights, responsibilities and entitlements and are able to exercise them to pursue full and independent lives.’ | 167 | 71.4 | 50 | 21.4 | 9 | 3.8 | 3 | 1.3 | 5 | 2.1 |

| Outcome 3: ‘Refugees and asylum seekers are able to access well-coordinated services, which recognise and meet their rights and needs.’ | 176 | 75.2 | 43 | 18.4 | 6 | 2.6 | 2 | 0.9 | 7 | 3.0 |

| Outcome 4: ‘Policy, strategic planning and legislation, which have an impact on refugees and asylum seekers, are informed by their rights, needs and aspirations.’ | 141 | 60.3 | 59 | 25.2 | 21 | 9.0 | 4 | 1.7 | 9 | 3.9 |

N=235 (outcome 1); N=234 (outcomes 2 to 4)

The extent to which respondents felt that the Strategy’s outcomes were relevant to their organisation varied depending on respondents’ existing level of awareness of the Strategy. In relation to all four outcomes, higher proportions of those with high or medium levels of awareness (that is, they had helped develop the Strategy, had frequently referred to it, or had read at least some of it) perceived the Strategy’s outcomes to be quite or very relevant. This is most evident with regards to Outcome 4: 91% of those with high awareness viewed this as relevant, compared with 71% of those with low awareness.

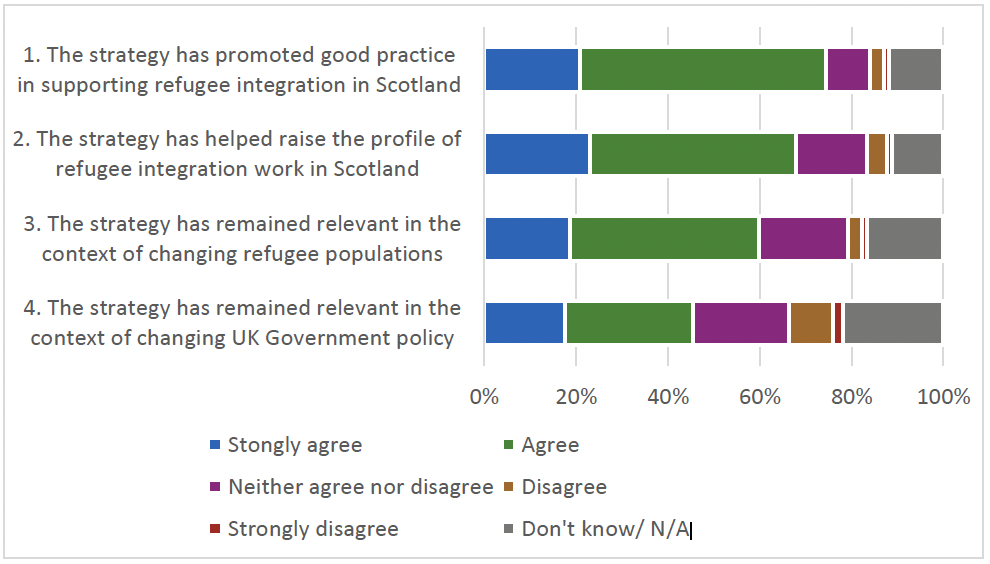

Survey respondents were asked to indicate how much they agreed with a series of statements relating to the profile and relevance of the New Scots Refugee Integration Strategy (see Figure 3.1). Responses to the first three statements were positive, with the majority agreeing that the Strategy has promoted good practice in supporting refugee integration (74%); has helped raise the profile of refugee integration work in Scotland (68%); and that it has remained relevant in the context of changing refugee populations (60%). Responses to the fourth statement (“the Strategy has remained relevant in the context of changing UK Government policy”) were not as positive, though 45% agreed overall. It is notable that a significant percentage of respondents (between 11% and 22%) answered either “don’t know” or “not applicable” to each of the statements.

Survey respondents’ perceptions of the profile and relevance of the New Scots Refugee Integration Strategy varied depending on their awareness of the Strategy. The highest levels of agreement that the Strategy helped raise the profile of refugee integration work in Scotland and remained relevant in the context of changing refugee populations and UK government policy, came from respondents with high awareness of the Strategy. Levels of disagreement and ‘don’t know’/’not applicable’ responses were highest among those with low awareness of the Strategy.

3.2.3. Understanding of the New Scots Refugee Integration Strategy

In the interviews, stakeholders were asked about their understanding and awareness of the New Scots Refugee Integration Strategy and what it set out to achieve. As might be expected, given their varying levels of awareness of the Strategy cited above, the stakeholders reported a range of knowledge and understanding of the Strategy from the highly detailed to a very broad concept of its scope and aims.

Stakeholders from a wide range of organisations described the New Scots Refugee Integration Strategy as being an overarching framework, an aspirational statement and a progressive, holistic document which aimed to address every aspect of refugee and asylum seeker integration in Scotland. It was also stressed that the Strategy embraced the principle of partnership working, and intended to involve and engage with refugees, and those working with refugees, actively, being deliberately collaborative in its nature.

“My understanding is that it is a national Strategy to promote, foster, encourage the integration of refugees and asylum seekers from day one to help people who arrive here to rebuild their lives and it has a holistic approach affecting every area of people’s lives who arrive here and…I guess it’s a tool to be used by organisations to help them think holistically about integration.” (Stakeholder interviewee)

“It’s a policy framework that organisations and institutions and individuals can kind of look to as a guiding framework for how we conduct our work to ensure that it does include refugees and that it does, the kinds of projects that we do support integration and it’s kind of something that we can use to hold other institutions to account…it’s a set of shared values which I think are pretty good actually and I think that most people at least who work in the sector would agree with”. (Stakeholder interviewee)

It was also emphasised that the New Scots Refugee Integration Strategy was a ‘welcoming’ document, and aimed to embrace refugees and people seeking asylum by making it explicit that they were new Scots as soon as they entered the country. This was viewed as differentiating the Strategy from UK governmental policy in the same area, though it was also added that the lack of Scottish governmental control over the policy area undermined this to some extent.

“Now there are arguments around whether we have the resource to provide what it wants, whether in reality you have the resource to provide what a policy states, sometimes it can be disparate but the intention is there and the intention is clear cut from the day you arrive which I think is something that ought to be celebrated.“ (Stakeholder interviewee)

The current New Scots Refugee Integration Strategy was seen to have developed from the first Strategy, though it was broader in nature and crucially was viewed as moving beyond the central belt of Scotland in its scope. As a result of the Syrian resettlement programme, the second Strategy was perceived as addressing the integration of refugees across other areas of Scotland, including rural and island communities. During the development of the second Strategy, stakeholders worked to facilitate and improve community engagement across Scotland. This was accomplished through network building and providing funding to a range of community groups and local authorities, to contribute to the development and implementation of the second New Scots Refugee Integration Strategy.

Other stakeholders expressed a more limited knowledge of the Strategy. This could relate to being part of a thematic group and only having knowledge of the aspects of the Strategy that related to the activities of the group, or a result of representing organisations with a specific interest (e.g., housing, education or language) and being aware of elements of the Strategy that were relevant to these issues. However, awareness and knowledge of the Strategy were said to have increased for organisations when they sought funding for their work with refugees and people seeking asylum. AMIF funding was frequently mentioned in this regard, though other funding applications were also cited. When these applications were made, the Strategy was reviewed and referred to in the application documents.

Finally, stakeholders in more strategic roles, not as directly involved in project delivery, argued that a widespread understanding and knowledge of the Strategy was not necessary, particularly for those working with refugees ‘at the ground level’ in local communities or among refugees and people seeking asylum themselves. Indeed, stakeholders reported that some initiatives had pre-dated both variants of the New Scots Refugee Integration Strategy, and continued to conduct good work even if knowledge of the Strategy was minimal within the implementing organisations. Where these initiatives used principles underpinned or endorsed by the Strategy, with or without a thorough understanding of the Strategy, stakeholders were comfortable with such an approach.

3.3. Implementation of the New Scots Refugee Integration Strategy

Through the analysis of data from the stakeholder survey, stakeholder interviews and the Matter of Focus workshops with AMIF-funded projects, the following research questions were addressed:

- What is working well/not well in how the New Scots Refugee Integration Strategy is being implemented? Does this vary between groups/areas?

- What contextual factors influence implementation?

- What are the factors that block successful implementation, and what factors enhance it?

- Has the intended reach been achieved?

- What elements of the New Scots Refugee Integration Strategy are working well, and what elements are working less well?

- To what extent has the absence of a structured funding arrangement impacted the New Scots Refugee Integration Strategy and implementation, and how would the continuation of this policy impact future practice and implementation?

- How have the outcomes of the New Scots Refugee Integration Strategy benefited from the partnership approach to policy and implementation?

This section covers participants’ views on the implemention of the second New Scots Refugee Integration Strategy. This includes survey respondents’ and stakeholder interviewees’ views on what worked well and helped to progress the aims of the Strategy, as well as a discussion of those aspects which were perceived to be more challenging and hindered progress. First, it considers how the Strategy was used by stakeholders.

3.3.1 Use of the New Scots Refugee Integration Strategy by stakeholders

A series of questions in the survey related to how the New Scots Refugee Integration Strategy had been used by stakeholders and the extent to which the Strategy had impacted on the work of organisations.

The majority of respondents (72%) said that the overall impact of the Strategy on the work of their organisation had been either ‘very’ or ‘quite positive’ (only 2% said that it had a negative impact) (see Table 3.3). In addition, 86% of those with high awareness of the Strategy reported that its impact on the work of their organisation had been favourable.

| What has been the overall impact of the New Scots Refugee Integration Strategy on the work of your organisation? | ||

|---|---|---|

| N | % | |

| Very positive impact | 32 | 18.2 |

| Quite positive impact | 95 | 54.0 |

| Neither positive nor negative impact | 32 | 18.2 |

| Quite negative impact | 1 | 0.6 |

| Very negative impact | 2 | 1.1 |

| Don’t know | 9 | 5.1 |

| N/A | 5 | 2.8 |

| Total | 176 | 100 |

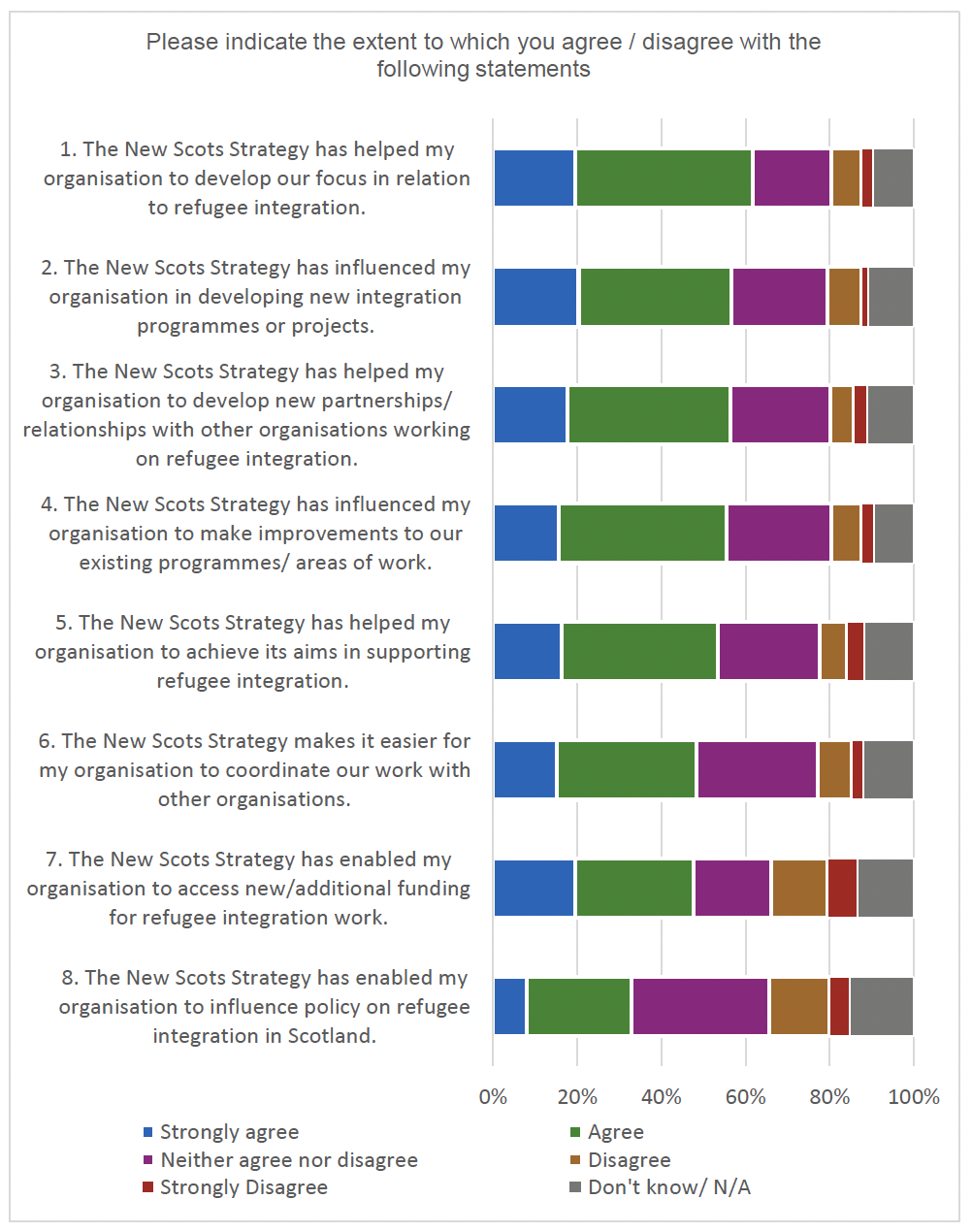

Survey respondents were asked to indicate their level of agreement (from ‘strongly agree’ to ‘strongly disagree’) with a series of statements which related to how the Strategy had influenced the work of their organisation. The extent to which the Strategy was perceived to have influenced the work of organisations varied (see Figure 3.2).

The highest levels of agreement from respondents were in relation to statement 1, “The New Scots Strategy has helped my organisation to develop our focus in relation to refugee integration”, with which 62% agreed. More than half of respondents agreed the Strategy had influenced their organisation in developing integration programmes or projects (57%); that it helped their organisation to develop new partnerships/relationships with other organisations working on refugee integration (56%); that it had influenced their organisation to make improvements to their existing programmes/areas of work (56%); and that it had helped their organisation to achieve its aims in supporting refugee integration (53%).

Agreement was lower in relation to the last three statements illustrated in Figure 3.2. Fewer than half (48%) agreed that the Strategy made it easier for their organisation to coordinate their work with other organisations, while 48% agreed that the Strategy had helped their organisation to access new/additional funding for refugee integration work. A third (33%) agreed that the New Scots Refugee Integration Strategy had enabled their organisation to influence policy on refugee integration in Scotland. Almost a fifth disagreed with these last two statements.

Agreement with all eight statements was highest for those with high levels of awareness of the Strategy. Between 9% and 15% selected ‘don’t know’ or ‘not applicable’ in response to these statements. This was linked with low levels of awareness of the Strategy.

Survey and interview data provided further examples as to how stakeholders and their organisations used the Strategy in their work.

Partnerships and messaging

Stakeholders identified the ways in which they had used the New Scots Refugee Integration Strategy to better understand the partnerships surrounding refugee integration and the work of other organisations. Stakeholders noted the Strategy had helped to build or strengthen these partnerships as it facilitated better coordination. For example, they thought this came about as a result of understanding the roles and responsibilities of different organisations involved in the theme groups, as well as giving stakeholders the opportunity to share their learning and concerns within their local areas. Stakeholders and survey respondents also mentioned that the Strategy inspired them to network with others more comprehensively, by providing opportunties to build new links with organisations and individuals and further develop existing ones.

“We have been encouraged to make better links with other organisations working to the same objectives.” (Survey respondent)

“It has created a network within Scotland who are looking at different ways to support asylum seekers through each part of their journey.” (Survey respondent)

“Well I think it’s definitely facilitated more joined up support because before having [an] effective Strategy, different groups doing their own thing, Local Authorities doing their own thing and if you’re a refugee or a local community where something good happens to be happening then you benefit from it but you could be in a complete blackhole where nothing is happening and you’re still dealing with the situation. So I think it’s definitely moved us in a positive direction from that point of view and I think it has also raised awareness at government level” (Stakeholder interviewee)

Relationships developed through the themed groups were viewed very positively. A group member talked of how important it was to be able to “see the value and strength” of the different organisations they worked with in their group, while another noted their theme group had resulted in a sharing of ideas and better relationships and connections between organisations.

Stakeholders emphasised that the Strategy was helpful in promoting a welcoming atmosphere for refugees and people seeking asylum, setting a precedent to help them settle in Scotland and build their lives from day one in the country.

“The Strategy also provides reassurance to refugees and asylum seekers in Scotland about their position in this country. This reassurance is vital for people who are building new lives after experiencing very difficult and often traumatic circumstances. As part of our work to support people, we can refer to the Strategy when we are exploring their rights and responsibilities in Scotland to better inform them.” (Survey respondent)

Funding opportunities

Stakeholders from third sector organisations and local authorities stated that it was helpful to refer to the New Scots Refugee Integration Strategy when making funding applications for service provision (e.g., training, ESOL, staffing) to ensure their work reflected policy objectives. Funding was sought from the Scottish Government and other funding sources. Some stakeholders had received funding for work directly related to the themes outlined by the Strategy. Some interviewees had prepared joint funding bids with other organisations involved in the New Scots Refugee Integration Strategy theme groups, while other stakeholders had referenced the Strategy as support in their applications for other types of funding.

“So we used it [the Strategy] to frame a lot of what we did. It's helpful in terms of funding, because you had something tangible that you could point towards and say, 'Look, this is, we're working within this larger framework, a strategic framework with clear priorities. This is one that we can help to meet, and here's how.' So, it was helpful in that way but also, helpful as a guide, I suppose.” (Stakeholder interviewee)

A framework for integration

It was common for stakeholders to refer to the benefits of the New Scots Refugee Integration Strategy in providing a common framework, or ‘starting point’, to inform the development of their organisation’s work. This allowed staff within organisations to consider the use of their services by refugees and people seeking asylum and possible reasons behind the lack of uptake. The Strategy was said to have raised cultural and social awareness and enabled stakeholders to take action within their organisations to make their services more accessible to refugees and people seeking asylum. For example, provision of child care, interpreters and prayer rooms can help with the uptake of services. Stakeholders said they also used the Strategy to determine how their organisations would best align with the Strategy’s themes to identify where the work of their organisation could add value, and potential avenues for work that contributes to multiple themes outlined in the Strategy.

“I think the Strategy gave our work a framework, an idea and thoughts around where and how we could fit in as an organisation within that umbrella, so I think that the direction, the processes, the areas of work that we chose to work on was motivated I suppose by the Strategy.” (Stakeholder interviewee)

Interviewees also reported that they had used the New Scots Refugee Integration Strategy to inform their signposting to organisations that worked in other areas, for example, in terms of mapping their engagement work with stakeholders. This helped organisations develop a better understanding both of the population they serve and of other organisations working in the area.

Stakeholders from local authorities and AMIF-funded projects said they had used the Strategy to guide and frame their work with refugees and people seeking asylum. For example, using the Strategy as a resource for those newly in post in an organisation so they could better understand what they were hoping to achieve. It was added that their organisations had developed their work around the key concepts provided by the Strategy to help them connect the work they were doing to national policy.

“New Scots 2 gave me that [framework]; without that, I would've really struggled to know where to start. I had the notions, I had the concepts; I didn't have the structure and the framework. So for me, New Scots 2 has been really, really important to be able to connect what we do in [organisation/location] into what's happening at Scottish Government level as well.” (Stakeholder interviewee)

Reasons for not using the New Scots Refugee Integration Strategy

In both the survey and the interviews, there were respondents who said they made little to no use of the New Scots Refugee Integration Strategy. Written responses to an open-ended question[28] from survey respondents who had not used the Strategy showed that this was often due to not having been aware of it. This included organisations with a direct remit to support refugees and people seeking asylum and organisations with a wider remit. Other common responses to the open-ended question included not having the capacity to utilise the Strategy due to being a small/newly-formed group or lacking the resources to do so, and believing the Strategy to be irrelevant to their particular work or current focus. Some respondents thought that the Strategy was unnecessary for them as it was similar to work they were already carrying out while others said they had not used the Strategy because they thought there was no support in implementing the Strategy.

“With a wide remit, our work to support refugee integration is a very, very small part of our work. I don't believe the New Scots Refugee Integration Strategy is well known across my organisation and this has had an impact on how well it can inform organisational work. Greater national focus and publicising of the Strategy may improve that.” (Survey respondent)

“We were aware of the broad principles but as far as I am aware there was no help available to third sector organisation[s] on how they could implement and what support would be available. The document seemed to set out aspirations but was lacking in any detail of how these would be achieved practically.” (Survey respondent)

In the survey, respondents were also asked to “briefly summarise how the New Scots Refugee Integration Strategy has been helpful to your organisation in its work to support the integration of refugees and people seeking asylum in Scotland between 2018 and 2022?” They were given an open-text box to write in. In response to this question, a number of survey respondents from local authorities, third sector organisations and statutory bodies explicitly said that the Strategy had not been helpful to their organisation or work. Several noted simply, “it hasn’t”, without providing an explanation. Others were more expansive in their responses for example stating that they thought the Strategy was too vague and lacked strategic coordination to help inform their work. While the Strategy provided a vision for integration, stakeholders said it did not provide details on how this vision could be achieved and what organisations could do to achieve this vision.

“It has helped shape the direction of some of my personal work programme but not the wider organisation work programme. I don't believe the work within the New Scots action plans are well co-ordinated, organised or monitored enough to have the impact they were intended to. The work has often felt a little unclear and this has limited how and where I (and my organisation) am able to contribute and support it best.” (Survey respondent)

Stakeholder interviewees noted that the New Scots Refugee Integration Strategy had not influenced the focus of their organisations’ work, largely because they had already been working along those lines due to the Strategy’s intended outcomes being aligned with their organisation’s own aims and objectives. While the Strategy did not influence the focus of their work, some noted that the Strategy had helped to validate their work and helped stakeholders to see how their work was contributing to national policy.

“The Strategy, I mean it’s helpful to look at that diagram from time to time but I think we think along the same lines as that Strategy in a way. The Strategy has been more of a confirming thing and actually yeah it does help to make us realise again that we don’t have that lead role in ESOL and employment but maybe there are things we can do just to support it in some way.” (Stakeholder interviewee)

There were also stakeholder interviewees with more conflicting views on how the work of their organisations aligned with the Strategy’s aims. In these cases, the Strategy was considered as more of a resource rather than a prescriptive guide.

“Well the thing is it does align with our organisation’s aims and objectives but I guess there is a bit of a question of would we have the same aims and objectives even without the Strategy and actually I think we would probably work in a very similar way even without the Strategy… the specific outcomes are relatively vague so actually there’s a lot of work that can fit under these outcomes and the targets aren’t necessarily… there’s no plan attached to them.” (Stakeholder interviewee)

The activities of the New Scots groups

In the interviews, stakeholders who were members of the New Scots core or themed groups reflected on the types of activities their groups had undertaken between 2018 and 2022. Broad activities mentioned by group members included:

- Administering and distributing AMIF funding;

- Engaging with stakeholders;

- Lobbying policy makers and other groups to promote the rights of refugees and people seeking asylum (e.g. right to vote, hotel accommodation);

- Supporting refugees and people seeking asylum during the pandemic (e.g. addressing basic needs, providing digital devices);

- Developing action plans linked to the Strategy, including incorporating additional theme of digital support and inclusion;

- Exploring the provision of information and pathways (e.g. regarding the asylum process);

- Providing training and raising awareness amongst stakeholders on the needs of refugees and people seeking asylum;

- Coordinating joint funding bids between organisations represented in the groups.

Examples of specific activities undertaken by key groups, and cited in interviews with stakeholders, included:

- The Employability and Welfare group worked with employers and looked at the recognition of people’s prior learning. They also sought to ensure refugees and people seeking asylum were accessing their rights and entitlements (e.g. benefits);

- The Health and Wellbeing group sought to ensure complaint procedures in relation to health services are understood by refugees, and produced an interpreters’ policy;

- The Housing group developed welcome packs for refugees;

- The Education and Language group explored access to ESOL and responded to the ESOL consultation.

When asked to reflect on the types of activities undertaken within their group, it was notable that members often found it difficult to describe exactly what activities had been conducted, and the activities outlined by respondents did not always tally with those outlined in their group’s published action plan. This finding suggests a need for adaptable action plans and improvement to communication between key groups.

The activities of the AMIF-funded projects

In order to make a contribution to the New Scots Refugee Integration Strategy outcomes, AMIF-funded projects delivered a diverse range of interventions based on their own specialisms and local needs. There were projects that planned to focus on implementing innovative work to support integration, while other projects planned to use the funding to extend existing work, in some instances to new geographical areas, through outreach and accessibility adaptations. All funded projects were required to focus on at least one of the themes underpinned in the Strategy: housing; health and wellbeing; employment and welfare rights; education and language; needs of people seeking asylum; and communities, culture and social connections. Projects implemented a range of approaches in working with refugees and people seeking asylum to improve integration including: providing ESOL classes; using creative/arts-based techniques to enhance inclusion or provide information; mentoring; teaching digital literacy, and workshops for children and parents. In the group of 12 AMIF-funded projects that Matter of Focus engaged with, many were using creative and arts-based interventions which included a range of types of media such as film, photography and creative writing. Projects highlighted that a wide range of artistic and creative activities were both positive for engaging communities, especially when language is a barrier, and in enabling individuals to create channels for telling their stories as a therapeutic tool. Given that these projects were ongoing during the time of this evaluation, it was not possible fully evaluate the outcomes of their work. However, all funded projects will be providing evaluation reports to the funders, and key findings from these will be developed into case studies and an overarching evaluation report for the AMIF-funded projects during 2023.

3.3.2. Factors enabling implementation of the New Scots Refugee Integration Strategy

Stakeholders were asked in both the survey and the interviews to consider what had worked well in the implementation of the New Scots Refugee Integration Strategy, and what factors had enabled its implementation. AMIF-funded projects which worked with Matter of Focus were also asked to consider this. The key enablers identified included the role of partnership working, positive messaging and staff goodwill, funding, and adaptability and relevance of the Strategy.

Partnership working

The role of partnership working between organisations engaging with refugees and people seeking asylum was viewed as a key facilitating factor in implementing the New Scots Refugee Integration Strategy by stakeholders in the survey and interviews. This included partnerships between government, local authorities, and the third sector as well as between different third sector organisations, community or faith groups.

“It has a broad representation of organisations with differing interests in the field of asylum support. There are pockets of specialism around government frameworks which enable a greater understanding of legislation which benefits asylum seekers and refugees. There is a commitment to work collaboratively, regardless of politics.” (Survey respondent)

Interviewees praised the involvement of lots of organisations all working to help refugees and people seeking asylum settle in Scotland. Working with a range of organisations was viewed as being helpful in spreading the word about the New Scots Refugee Integration Strategy and aiding communication with partners. Partnerships developed in the course of implementing the New Scots Refugee Integration Strategy were also said to have enabled organisations to respond flexibly and quickly to challenges. This was deemed particularly useful during the lockdowns put in place during the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020 and 2021, and in response to critical incidents such as the case of the Glasgow hotel attack on the 26th June 2020[29]. Core and theme group members noted this allowed the groups to respond and mobilise to help people.

“Every crisis brings new challenges but if you've got a framework within which you could set those challenges… [then] you've got some established ways of working that the Strategy has helped put in place. It makes the uniqueness of each individual crisis a bit easier to deal with.” (Stakeholder interviewee)

Collaborative working was also viewed as integral to the successful work of the New Scots core and theme groups. Most participants focused on the longstanding relationships built up over many years of working together with the same organisations and individuals, highlighting the benefits of building connections and networking between organisations. Some of these relationships existed before involvement in the Strategy, while others developed as a result of participating in a theme group. Stakeholders who were part of New Scots core and theme groups highlighted the importance of their relationships with other organisations in implementing the Strategy.

“It’s people’s lives and it’s all aspects of people’s lives. So no one body, or no one organisation or government can actually support, address, work with all people’s aspects, life aspects, so you need that partnership and you need that collaboration because if that doesn’t happen whatever actions, it doesn’t matter how much funding you put towards actions it will not work. So for me that is the most positive thing.” (Stakeholder interviewee)

Clear communication and promotion were considered central to partnership working to deliver the New Scots Refugee Integration Strategy’s outcomes. Stakeholder interviewees spoke of the benefits for refugees and people seeking asylum in terms of information sharing between different types of organisations. These benefits included developing clear lines of support for refugees and people seeking asylum, and improvements in signposting to other organisations.The core and themed groups were perceived as an important means of hearing about local and national developments and of communicating with the Scottish Government through what was a described as a “two-way flow of intelligence” gathering and sharing.

A related factor mentioned by survey respondents was the fact that the Strategy was viewed as relevant and widely applicable to any refugee group.

"Being national in scope - helped to provide consistent messaging and a framework as a base for local authorities, organisations and communities developing integration support and services for the first time. Local authorities in particular have stepped up to support people through a variety of resettlement and displacement routes since the Strategy was developed and third sector support organisations have expanded their work into new areas or developed from grass roots. A clear vision and principles have helped to bring together organisations, services and communities to contribute to shared outcomes." (Survey respondent)

Linked to partnership working was the importance of working with people who had lived experience of being a refugee or of seeking asylum to develop AMIF-funded projects. For example, a survey respondent noted how working with refugees and people seeking asylum helped to shape the delivery of projects to ensure that the projects met the needs of refugees and people seeking asylum, both in terms of addressing issues relevant to them and making the projects accessible to them (e.g., providing child care, interpreters etc). The ability of those involved with implementing the Strategy to lobby relevant bodies and to ensure the needs of refugees and people seeking asylum are heard was also highlighted. Interviewees referred to the successful campaign to lobby UK and Scottish Governments to allow for the funding of laptops and wi-fi during lockdown.

Stakeholders referenced the importance of collaborative working with partner organisations, particularly the Scottish Refugee Council. It was felt they were vital to the New Scots Refugee Integration Strategy, allowing other organisations, including those which received AMIF funding, to connect more to the Strategy, especially those who were not aware of it. Interviewees valued the involvement of academics in helping to generate a research base which enabled evidence-based strategic decision-making. The input of Scottish Government was also perceived positively, given the potential to link to other policy areas, supporting links to these, and the provision of a framework to look at the needs of refugees in relation to individual policy areas, such as health and housing.

Positive messaging of the New Scots Refugee Integration Strategy

Stakeholder interviewees, survey respondents, and AMIF-funded projects highlighted the benefits of the positive messaging of the New Scots Refugee Integration Strategy of being welcoming and inclusive of refugees and people seeking asylum, often contrasting this with the perceived negative messaging of the UK Government in relation to refugees and people seeking asylum. They felt that framing refugee integration in a positive and welcoming way aided buy-in from stakeholders and their organisations as it reflected the values and commitment from their own organisations.

“It’s good to have principles based on being welcoming and inclusive, rather than the UK’s ‘hostile environment’.’’ (Stakeholder interviewee)

The uniqueness of the Strategy within the UK context motivated those commited to the rights of refugees and people seeking asylum to get involved in implementing the Strategy, for example by being a member of one the New Scots themed groups. It was also felt that the infrastructure around the Strategy (e.g., the core and theme groups) helped to give refugee and asylum issues greater prominence than if it had been a single organisation working on their own to progress this agenda.

While the vision of the Strategy motivated organisations to be involved in implementing the Strategy, overall stakeholders said that progress towards achieving the Strategy aims was a result of the goodwill and determination of core and themed group members and other organisations. Individuals and organisations were commited to progressing integration and improving the lives of refugees and people seeking asylum in Scotland, as a result of which they continued to work without dedicated funding, leaving some feeling burnt out.

More widely, the enthusiasm, resilience and commitment of the people engaged in the Strategy were viewed as key enablers of implementation. A stakeholder interviewee praised other stakeholders’ resilience which, for example, enabled creative responses to challenges around digital inclusion and connectivity during the COVID-19 pandemic. A collegiate way of working was perceived to be particularly important in light of the fact there was no funding attached to the New Scots Refugee Integration Strategy. This meant people had to work together and use available resources, with the ‘goodwill’ of those working in roles supporting refugees and people seeking asylum frequently mentioned. An interviewee commented on the considerable achievements of the Strategy and those involvement in implementing it.

“The Scottish government can find small amounts of money to publish a report or to host a conference, but it's not really funded, and the people who go along to it, the policy people from the corporate headquarters of national Scottish organisations come along in their own time. So that sounds like a criticism of New Scots, which it isn't really. It's done what it's done on almost no budget and out of a spirit of multi-agency professional collegiality, and it's produced Strategy documents about what the key levers of integration are, and thematically across some of these key themes, like health, education, housing, work, welfare. That's been picked up on internationally and been commented on approvingly internationally. So to be realistic on what can you get for a three monthly meeting of people who are finding space in their own diaries to do it and it's something that's otherwise unfunded, actually, they probably punch way above their weight really, given the international recognition of New Scots. Certainly, those sentiments, I can clearly recall being uttered by the Scottish Refugee Council, by the Mental Health Foundation. Perhaps also the British Red Cross.” (Stakeholder interviewee)

AMIF funding

In light of the lack of wider funding attached to the Strategy, the provision of the AMIF funding to local authorities, third sector organisations and community groups was seen as key to the successful implementation of the New Scots Refugee Integration Strategy. The AMIF-funded projects were said to have aided implementation through delivering work which captured learning in relation to refugee and asylum seeker integration. It was argued by stakeholders that through these projects, implementation of the Strategy was able to take place on the ground. The launch of the AMIF funding was perceived to have contributed to greater awareness of the issues facing refugees and people seeking asylum amongst organisations and groups that could play a role in integration. Similar points were made by survey respondents.

"The widespread use of funding for smaller organisations across Scotland is very important. The variety of the projects supported is also very important including, for example, support into employment which is crucial for refugees." (Survey respondent)

There were, however, mixed views among stakeholders as to how well the AMIF projects had been promoted to organisations working with refugees and people seeking asylum. Some interviewees felt that greater recognition of the contribution of the AMIF projects would help improve the morale of those working in the sector. Some felt that the New Scots Refugee Integration Strategy is better known because of the existence of the AMIF fund. Others expressed disappointment that the work of the AMIF projects had not received greater exposure, stating that this would have helped to expand the reach of the wider Strategy.

“But there was also something that was kind of disappointing about this process which was that it didn’t really feel like the projects that got funded were really celebrated that much and it wasn’t like there was a lot of noise made about it and I kind of gathered that that was because a lot of people had got turned down, a lot of the kind of key refugee support organisations, so we felt a bit like well that is sad for them but like we’ve been funded by this for the first time and like that doesn’t…it just felt like the politics of the kind of sector kind of got in the way of enough noise being made about it which in terms of people being aware of the Strategy and saying that its making an impact in their communities is really important.” (Stakeholder interviewee)

Adaptability and relevance

The ability to adapt the New Scots Refugee Integration Strategy to make it relevant to the changing contexts in which it might be implemented was another theme raised by stakeholders. Interviewees pointed to the ways in which individuals and organisations had adapted to the intake of new refugee groups (e.g. people from Ukraine), while others felt that these different resettlement schemes had themselves helped to raise awareness of the Strategy. The ability of the Strategy to respond to the changing environment was praised by some interviewees, for example, the decision to add digital inclusion into the Strategy in response to the impact of COVID-19. This was accomplished through lobbying for Scottish and UK Government grants by partners within the News Scots Refugee Intergration Strategy core group. Others noted that the flexibility of the Strategy helped ensure organisations were in a better place to respond when needed, for example in terms of adapting support needed for new groups of refugees, such as those who arrived from Ukraine.

“I think the strength of New Scots 2 is, it feels like a live document, it feels like a live Strategy, it feels like something that isn't frightened to evolve or isn't frightened to say, 'It's maybe not right.' It's also not frightened to say it doesn't get it right all the time either. It doesn't feel like a tablet of stone, which is really helpful I think for those - like myself - who have only joined the refugee community [more recently]. But that framework was really important and me being able to watch the development of that and be able to reflect that in how we deliver here, just for that feeling of connectivity is really, really important, and not feel that we are adrift, that we're anchorless! Or that we can then be pulled in different directions. It's really important that we can still stay connected into what the rest of Scotland is doing.” (Stakeholder interviewee)

3.3.3. Factors hindering implementation of the New Scots Refugee Integration Strategy

Survey respondents and stakeholder interviewees highlighted a range of barriers to the successful implementation of the the New Scots Refugee Integration Strategy. It should be noted that a wide range of barriers were identified, and their impact on the successful implementation of the Strategy was viewed as being considerable. These included: the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic; lack of funding to support the implementation of the Strategy; reserved policy making; governance of the Strategy; local government challenges; lack of access to services; lack of public awareness of the Strategy; limited engagement with those with lived experience; and the Ukraine war.

COVID-19

The impact of COVID-19 was frequently raised by AMIF-funded projects and stakeholders responding to the survey and in interviews. There was a perception that the pandemic and its associated lockdowns had reduced individuals’ and organisations’ abilities to achieve the Strategy’s actions. This was because staff and resources were diverted elsewhere, integration services were disrupted or suspended, or time was needed to adapt to remote and digital delivery. Lockdowns also meant that services could not deliver in-person support and not all refugees and people seeking asylum felt comfortable engaging digitally, either because of language barriers or confidence using digital technology. The pandemic caused distruption to services that support integration such as ESOL and employabilty support.

“Half of the intended duration for implementation of the Strategy occurred during the COVID-pandemic, when services and resources at all levels were redirected and adjusted to respond to the crisis and recovery. There is a likelihood this alone will have posed a significant obstacle to fulfilling the outcomes of the Strategy.” (Survey respondent)

Despite disruptions to integration services, there were stakeholders who highlighted how COVID-19 helped to address challenges for people seeking to access support in rural areas. For example, by switching services from face-to-face to online, some refugees and people seeking asylum were more likely to attend ESOL classes and access other support services.

“We use language sometimes about hard-to-reach groups outwith [the] Central Belt, but it's not. It's hard-to-reach services, not hard-to-reach groups! So obviously the moving things online actually helped to some extent for a lot of rural communities, so for instance a lot of our clients were able to access things like, [support organisation] run some training which [rural area] clients were able to take part in, which we have never been able to do before because these women would never have been able to travel to Glasgow. […] They wouldn't have taken part. Because of being able to do it online, so actually COVID gave us quite a lot of opportunities in terms of being able to connect in, to be able to attend things - because they were online.” (Stakeholder interviewee)

Among New Scots group members, it was felt that redeployment of Scottish Government staff to deal with the effect of the pandemic negatively impacted on the groups and the wider implementation of the second New Scots Refugee Integration Strategy. Government staff were not available to help support the implementation of the Strategy which put more pressure on other organisations to take the Strategy forward with limited government support.

“COVID has kind of done for the Strategy in some respects because we’ve not really been meeting, people have been too busy and the Scottish Government, like every government, has put everything aside to deal with COVID and the Strategy has suffered as a result. People have been moved out of the departments they’ve been working in to concentrate on COVID and they’ve not necessarily been replaced, or they’ve been replaced by people who don’t really know very much about the Strategy.” (Stakeholder interviewee)

This, combined with the changing of group members brought on by factors such as staff “burnout” across the sector and redeployment of staff, was said to have led to some stakeholders becoming disengaged from the theme groups.

Stakeholders noted a rise in the number of people struggling in terms of poverty and mental health as a result of the pandemic, and the movement of people seeking asylum into hotels. This meant that some organisations were more stretched, with COVID-19 impacting their organisational capacity and ability to respond. A stakeholder commented that “refugee integration stopped for 18 months”, while stakeholders tried to lobby UK Government to put provisions for people seeking asylum and refugees in place. Interviewees spoke of how the humanitarian response took precedence over the implementation of the New Scots Refugee Integration Strategy.

“We have literally had to stop people starving to death within the asylum system. We've had to try and mitigate the epidemic that, and the misinformation, disinformation and fear, and we've had to try and do that by engaging with many of the local refugee groups, so that they will do translation, they will help mitigate some of the disinformation. We've also had to try and deal with the big issue that came up, which was digital inclusion, when everything went into lockdown, that wasn't an element of the Strategy. It wasn't a big element of anything other than the education strand. Now it's critical.” (Stakeholder interviewee)

Stakeholder interviewees praised the response of organisations working with refugees and people seeking asylum, which quickly mobilised to provide more support. However, this impacted in multiple ways on the New Scots groups’ focus and on their membership. Several themed groups had not met since before the COVID-19 pandemic, while some meetings had moved online. Some organisations and individuals were not able to engage with the groups as much as they would have liked due to these changing priorities.

“That’s the impression I got from the meetings that everything was kind of falling apart because of COVID and people just being totally overwhelmed with having to switch to online learning and I don’t think this was anything…nothing to do with incompetence or lack of will, just logistics and everything being thrown into chaos.” (Stakeholder interviewee)

Lack of funding

A perceived lack of funding or specific budget for staffing and other resources associated with the New Scots Refugee Integration Strategy was considered by many stakeholders as one of the most significant factors hindering its successful implementation. Stakeholders noted this meant that the Strategy’s implementation was reliant on the goodwill of people working with refugees and people seeking asylum, their willingness to support the actions of the Strategy and their ability to make time for the work. This became increasingly challenging given the demands of COVID, the changing nature of the policy environment and different refugee crises. As a stakeholder commented, “It's all well and good to have a policy and Strategy without any cash behind it” but “goodwill only gets you so far”. Another cautioned that the lack of resources attached to the Strategy limited the commitment of those working in the sector to deliver it.

“I think for us I think there is a real challenge around there is no funding attached to the Strategy so what you’re setting out are all nice to haves, there’s nothing in the Strategy that is about…that links to a statutory service in the way that it’s a requirement that isn’t already kind of underway. It’s about trying to speed that work up I think is where the Strategy…the rest of it is based on goodwill and I think that has always been a massive problem with this Strategy.” (Stakeholder interviewee)

Stakeholders also pointed to the impact of wider funding issues in terms of having insufficient infrastructure to support refugees and people seeking asylum (e.g., interpreters, ESOL provision, employment support etc.), particularly in those areas of Scotland which were new to receiving these groups. Some felt longer-term, consistent funding for integration support services was missing, resulting in projects being started but not having the potential to become embedded and thus sustainable. Rising costs in general were also a concern.

“Due to funding restrictions and lack of resources we have been unable to concentrate activities in the area.” (Survey respondent)

“Lack of longer term funding for projects - short term funding enables work to start but not get embedded - funding is needed for longer periods of time, to really build the work and embed better practice and to build lasting partnerships and ways of working.” (Survey respondent)

Reserved policy making

A common theme in the stakeholder interviews and survey, and the work with AMIF-funded projects, was the detrimental impact of refugee policy being reserved to the UK Government. Stakeholders highlighted the difficulties of working within the UK Government’s policy agenda which was viewed as being at odds with the more supportive approach of the Scottish Government. It was felt that the UK Government’s stance was a barrier, ‘thwarting local attempts at establishing an environment of welcome’. Participants raised concerns relating to the fact that immigration is not a devolved matter and that therefore wider legislation and the Strategy do not relate to each other. Stakeholders expressed frustration that decision-making around asylum is a reserved matter, commenting that it limited the extent to which the New Scots Refugee Integration Strategy has been able to make a difference.

“Policy and current government at Westminster will always be the biggest obstacle to Scotland's policies on most things, especially asylum and human rights.” (Survey respondent)

Theme group members noted that while they had been able to make some progress around welfare in terms of making people aware of their rights and entitlements, the fact that people seeking asylum are unable to work meant they had not been able to make as much progress in terms of employability as they would have liked. An interviewee questioned whether it was possible within the current legislative context to support all elements of integration for people seeking asylum that would be expected from day one as set out in the Strategy (e.g. given that people seeking asylum do not have the right to work, to welfare benefits, or to mainstream housing).

“I think those are probably the key challenges around asylum. It’s the reserved nature of it and, as a by-product of that, the other structures and workstreams which are going on and taking up people’s time.” (Stakeholder interviewee)

Additionally, it was felt that the changing policy environment and the different resettlement schemes developed through the Home Office also limited implementation as a result of people’s rights and entitlements varying depending on their entry routes.

“I think the Strategy is really really challenged as well by…its not just asylum and what was at the time resettlement, we now have Afghan resettlement, Afghans in bridging hotels in Scotland, asylum seekers in bridging hotels in Scotland. The Hong Kong Nationals Scheme so all of these things are being developed at the Home Office, these bespoke different things with different rights and entitlements and different entry routes and the Strategy and the actors in Scotland are trying to make sense of all of this to say well everyone should be treated…every person coming to Scotland should be welcomed when you have a Home Office that are doing this thing of creating these bespoke programs and undermining the asylum system. So that is…that’s what I think is really challenging for the Strategy.” (Stakeholder interviewee)

Governance of the New Scots Refugee Integration Strategy

A third key theme raised was barriers related to governance of the Strategy, its status and whether legislation would increase its impact.

The fact that the New Scots Refugee Integration Strategy is not accompanied by a legislative framework was viewed as a hindrance by some stakeholders and AMIF-funded projects, as without a legislative framework they were unsure about its status and authority to command change. Without legislation, the Strategy was described as “toothless”, as there was no legal requirement for the Scottish Government to take action to implement the Strategy. This was said to further impact on the ability to engage and motivate people in the theme groups as they questioned their authority to action change. While some stakeholders suggested that Scotland’s policy framework is limited because of reserved policy making, others argued that there was more the Scottish Government could do to improve integration within devolved powers. Within the remit of devolved Scottish powers, stakeholders said Scottish Government bodies could do more in relation to improving ESOL provision, housing and promoting the rights of refugees and people seeking asylum. There were stakeholders who thought devolved powers were not being exercised fully, in part because, politically the government wanted to highlight the restrictions of UK Government policy. However, it is important to note that the Scottish Government is constrained in relation to making legislation on reserved matters.

“Performatively, the fact that the First Minister says, 'We welcome refugees', performatively that there is a refugees' minister now, that all matters a lot. But there are things within the legislative framework that could be undertaken that are not being undertaken because these kinds of things get used as a lever, as I understand it, for saying we can't do this until we've got independence. That is a frustration in Scottish Government.” (Stakeholder interviewee)

Despite the Strategy being a collaborative effort between partner agencies, some stakeholders perceived it as a Scottish Government initiative, particularly in terms of its management. A stakeholder expressed a view that the ‘balance of power has changed’ between the first and second Strategy. While they welcomed the increased role of COSLA and the Scottish Government in the second Strategy, they were concerned that this had been at the expense of third sector organisations.

“I suppose my fear is that it’s become more top down actually because it’s now the Scottish Government that obviously is really backing it which is great because they’re really supporting bringing in refugees, building the population and COSLA because they’re supporting refugees around the country they’ve got contracts to do that and so existing services there’s probably more of a balance of existing local authority services being more…a bigger part of the picture and third sector organisations being less of the picture.” (Stakeholder interviewee)

The centralised model of governance was highlighted by some themed group members. There was a perception that any changes to the groups’ action plans had to be agreed by the Minister. When action plans became outdated, this was felt to limit the progress of the groups[30].

“And so I think one of the dangers with having an Action Plan that feels quite so tied, so we weren’t allowed to change the actions because they would have to be approved by a Minister. But what that meant was you were then either tied to outdated actions or you were tied to an action that we wouldn’t be able to do anything about and then there was all these people doing all this amazing work that never got reflected.” (Stakeholder interviewee)

Stakeholders made reference to what they viewed as siloed departments at the Scottish Government, noting that the New Scots Refugee Integration Strategy is not fully understood by or linked to Scottish Government departments other than those directly responsible for policy relating to refugees and people seeking asylum. Interviewees also pointed to a perceived lack of joined up thinking between government departments and different strategies. A frequently referenced example was the ESOL Strategy which had been subsumed into the Adult Learning Strategy.

“As a result, ESOL is becoming much less important, is much less of a focus, just at the time actually when there needs to be massive[ly] more investment in it and that happened without even the courtesy of a notification to New Scots that that was happening. So that’s what I mean it’s not just that’s there’s not lip service, it’s just to a lot of civil servants we just don’t exist, and that’s disappointing.” (Stakeholder interviewee)

Some stakeholders perceived that there was too much bureaucracy associated with the New Scots Refugee Integration Strategy. Interviewees commented on the number of civil servants working to implement the Strategy themes, suggesting the many layers of accountability is detrimental to those engaging with refugees directly. Similar comments were made in respect of the various groups tasked with the implementation of the Strategy.

“There are too many structures, there is too much hierarchy that doesn’t, to my view, deliver anything except extra bureaucracy.” (Stakeholder interviewee)

Variation in local delivery approaches and geographic inequalities

Governance at a local level was another theme raised by AMIF-funded projects and stakeholders in the survey, interviews and Matter of Focus workshops. There were signs of a perceived misalignment between the New Scots Refugee Integration Strategy’s high level policy setting and its actual delivery and implementation on the ground.

However, it was also noted that there is a degree of variation between local authorities in terms of how the New Scots Refugee Integration Strategy has been implemented and the support provided to refugees and people seeking asylum. Some suggested that greater levels of coordination could have been provided through COSLA but that resources did not allow for this.

Tensions between national and local implementation and impact were also raised by stakeholders. The perception was that there was a lack of coordination between the Scottish Government and local government, and between government bodies and third sector organisations and community groups. Interviewees decribed the shift between the first iteration of the Strategy – which was perceived to be focused on the Central Belt – and the second Strategy – which was viewed as seeking to be more national in its outlook. However there were some interviewees who felt the current Strategy was still too Glasgow-centric, and to a lesser extent centred on the Central Belt, in both its development and delivery. On the other hand there were others who felt that the Strategy did not draw enough on Glasgow’s expertise of supporting New Scots.

“Considering that Glasgow City has received more New Scots than anywhere else in Scotland over the entire piece, you would think that there would be more concerted effort to engage with the areas that had the most experience around working with New Scots and trying to support them […] Yeah I think maybe the New Scots Strategy doesn’t pay enough attention to places and those experiences.” (Stakeholder interviewee)

Similar concerns were expressed in relation to membership of the themed groups, which some felt were overly focused on organisations based in the Central Belt. In the survey, the limitations of geographical inequalities (with refugees and people seeking asylum primarily placed in deprived urban areas) was also highlighted, as was the need for additional support for more deprived areas, which may face additional challenges in integration. It was felt that the experiences of organisations supporting refugees in rural areas was missing.

“It is still urban focused, and perhaps misses out the challenges and benefits for refugees resettled in rural areas. It also misses the strengths of rural programme and focuses on access to services.” (Survey respondent)

Access to ESOL provision and other services

AMIF-funded projects, stakeholder interviewees and survey respondents also outlined the ways that lack of access to services, especially ESOL provision, hindered the implementation of the New Scots Refugee Integration Strategy. For example, access to ESOL in some areas was limited partly by a lack of college-based provision and partly in terms of its accessibility to refugees and people seeking asylum (e.g., not being able to afford travel to access services or finding online-only provision inaccessible).

“I think language support is very necessary. Communication is a fundamental part of integration. There needs to be investment in ESOL, including tutor training, especially to develop skills in working with ESOL learners with no learning strategies and no literacy. Training of tutors to include a knowledge of CLD is necessary and ESOL tutors need better terms and conditions. I work with so many refugees who want to integrate and who want to work, but they are overlooked as their English is seen as 'not good enough'.” (Survey respondent)

A perceived lack of ESOL provision was also frequently mentioned by interviewees from across the themed groups. The provision of and access to language support were seen as a key barrier by members of all the theme groups and a crosscutting issue that was relevant to each. However, some noted that the structure of the theme groups meant that language issues could be considered the responsibility of the English and Language thematic group only rather than something which should be addressed by all the theme groups.

“I think there are some areas that were important but were then hived off to other themes. So as an example, one of the key areas for us is English speaking because all Health Services are provided in English right. So unless we deal with the English language issue we are not going to be able to bring parity across patient access and outcomes. But it was clear early on that the interpreting and language issues were being dealt with in a different group so we didn’t go near that.” (Stakeholder interviewee)

Stakeholders, AMIF-funded projects and refugees and people seeking asylum themselves, mentioned other services they faced challenges accessing. This included access to further and higher education, mental health services, employment and enterprise opportunities, accommodation, childcare support, internet connectivity, and faith-based services. Reasons services were challenging to access included: a lack of local provision; long waiting lists; travel and cost of access were prohibitive. Additionally, rules around eligibility meant some were excluded on the basis of their immigration status. Staff shortages and a lack of robust training within services were also thought to contribute to these difficulties.

Awareness of the New Scots Refugee Integration Strategy and refugees and people seeking asylum

A lack of public awareness regarding refugees, people seeking asylum and the New Scots Refugee Integration Strategy was identified as a further barrier to implementation. Stakeholders felt this lack of awareness extended to organisations and staff, particularly at the management, policy and funding levels, as opposed to the frontline staff working directly with refugees.

“I don't believe the New Scots Refugee Integration Strategy is well known across my organisation and this has had an impact on how well it can inform organisational work. Greater national focus and publicising of the Strategy may improve that.” (Survey respondent)

This lack of understanding included issues such as the length of time it may take for refugees to become integrated, the barriers to language learning, the extent of the impacts of the pandemic, and other challenges faced by refugees. Stakeholders also noted that refugees themselves were not fully informed of their rights, and the benefits and services available to them.

Further to this, participants said that the negative portrayal of refugees in the media contributed to an unwelcoming environment which hindered the Strategy, as this made it hard to ‘maintain positive integration work in communities’. These media portrayals were seen by stakeholders to perpetuate myths about refugees and people seeking asylum and negative attitudes within host communities.

“There’s a lot of negative views about refugee and asylum seeker communities, there’s a lot of myths about people faking it in a sense to come over and I think the reality is very very different and I think that the host communities there needs to be something to raise awareness around that so that host communities actually understand if you even compare it globally how many refugees the UK is taking for example and where are the refugees coming from and the way they’re treated and that it’s not a positive experience, the kind of houses they’re living in.” (Stakeholder interviewee)

Engaging refugees and people seeking asylum

Some participants said there was a lack of meaningful input into the the New Scots Refugee Integration Strategy from both grassroots organisations and those with lived experience of being a refugee or of seeking asylum. This was said to hinder the Strategy’s implementation in terms of its design, delivery and evaluation. Some described the adoption of a ‘top-down approach’ that was ‘not fully engaging the voice of New Scots’. Engagement that did take place with refugees and people seeking asylum (e.g., engagement events during the development of the Strategy) was perceived to be limited. Participants said they would have liked to have seen greater involvement of refugees and people seeking asylum throughout the design and implementation of the Strategy, including (but not limited to), involvement in the core and themed groups.

“Limited meaningful engagement of refugee representatives: e.g. no existing forums/structure within New Scots decision-making that provides meaningful advocacy and representation by and accountability to refugees. A New Scots advocacy group with representatives that sits alongside New Scots Core/theme groups perhaps.” (Survey respondent)

The Ukraine war

Another major event, the Ukraine war, was highlighted as having had an impact on capacity and resources to implement the New Scots Refugee Integration Strategy due to the need for involved organisations to divert their resources to support the sudden large-scale Ukrainian resettlement programme. AMIF-funded projects engaged in the Matter of Focus workshops said this led to increase demand and waiting lists for support. This was said to have contributed to staff burnout with organisations and individuals reportedly “overwhelmed” with workload.

“The war in Ukraine which again was unforeseen at Strategy development, but has increased refugees and created tension with divided Westminster policies of welcome for some refugees but deportation for others.” (Survey respondent)