Third Sector Resilience Fund: evaluation

Findings of an evaluation of the Third Sector Resilience Fund, announced by the Scottish Government in March 2020 and designed to provide emergency funding to third sector organisations which were struggling financially following the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic.

3. Use and impact of the funding

All organisations that received TSRF funding were asked to complete a monitoring form at the end of the funding period. The purpose of this form was to gauge how the funds were used and what difference the funding made to the recipient organisations.

Seven hundred and eighty-eight monitoring forms were completed by organisations in receipt of TSRF funding. A total of 785 organisations returned a monitoring form – this amounts to 57.2% of the 1,371 organisations in receipt of funding.[16] Most of the monitoring returns (79%) were returned between June and September 2020.

3.1 How the awarded organisations used the funding

Of all 788 returned monitoring forms, 571 included data that was deemed to be complete and robust enough to enable an analysis of how the organisations in receipt of funding used that funding.[17]

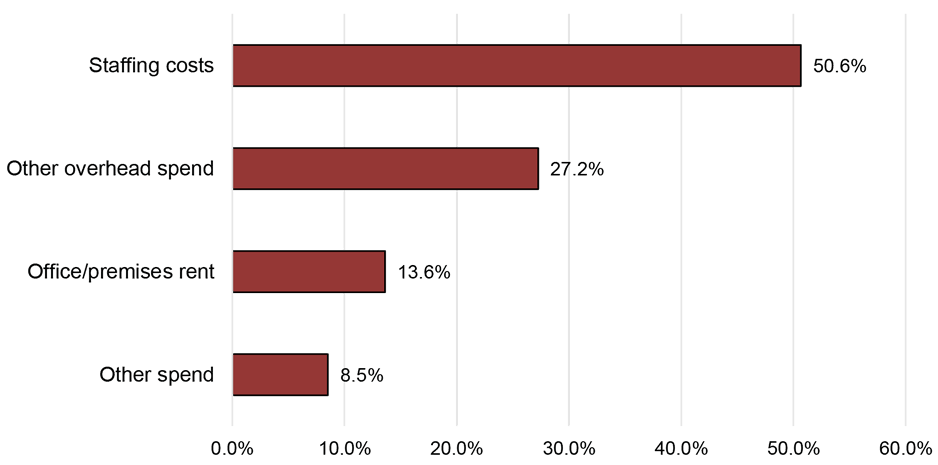

These 571 forms accounted for fund expenditure of £6,890,423. As Figure 15 shows, the majority of this funding was reported as being used for the three main purposes intended by the Fund. These were: to support the costs of staff who had not been furloughed; to make rent payments; and to pay other overhead costs.

Slightly more than half of funding (50.6%) was spent on staff costs, while 27.2% was spent on other overheads. Although the monitoring forms did not gather detailed information on the nature of spend on other overheads, when asked if they had any further comments, some organisations mentioned overheads such as insurance, membership affiliation fees, utilities and accounting. An additional 13.6% of funds were spent on rent payments.

As also shown in Figure 15, ‘other’ expenditure accounted for 8.5% of the spending. For organisations funded by Firstport, the data provide an insight into the types of spending that were classed as "other” spend on the monitoring forms. Based on the monitoring data collected by Firstport, 56 organisations recorded expenditure classed as ‘other’. Table 5 shows a breakdown of how this ‘other’ expenditure was used. The most common types of expenditure here were general running costs (as reported in 27.3% of monitoring forms), remote working and/or IT costs (17.9%), costs associated with buildings, sites, and construction (12.5%), costs associated with COVID-19 (8.9%) and supplier payments (8.9%).

| Type of "other" spending | No. of monitoring forms reporting each type of spend | % of monitoring forms reporting each type of spend |

|---|---|---|

| General running costs | 15 | 27.3 |

| Remote working costs/IT equipment | 10 | 17.9 |

| Building/site/construction costs | 7 | 12.5 |

| COVID-19-related spending (e.g. PPE, cleaning) | 5 | 8.9 |

| Supplier payments | 5 | 8.9 |

| Debt repayment | 2 | 3.4 |

| Subscriptions | 1 | 1.8 |

| Future-proofing | 1 | 1.8 |

| Refunds | 1 | 1.8 |

| Re-opening costs | 1 | 1.8 |

| Supporting volunteers | 1 | 1.8 |

| Unclear/unknown/other | 7 | 12.5 |

| Total | 56 | 100.0 |

3.2 Types of service provided and groups supported

All of the organisations that completed monitoring forms were asked about the types of services that they provide and about the groups that they support. Using data provided on 778 returns, Figure 16 summarises the types of services the monitoring forms said that funded organisations provided.[18]

The largest proportion of responding organisations (479, or 61.6%) said that they provided mental health and wellbeing services, while 304 (39.1%) said they provided physical health services. Two hundred and thirty (29.6%) organisations said they provided employment services and 213 (27.4%) provided food-related services. Smaller numbers of organisations said they provided home life or housing situation services (93 organisations, 12.0%) and money services (58 organisations, 7.5%).

Three hundred and fifty-seven organisations (45.9%) said that they provided ‘other’ services, with 134 (16.9%) choosing this category exclusively. Examples of the types of ‘other’ services provided by these organisations included services focused on children’s activities, education, religion and faith, community groups, social clubs, training, and animal welfare.

Organisations were also asked about the service users or communities that their organisation supported. Based on the responses from 596 monitoring forms, Figure 17 summarises the responses received.[19]

The largest share of organisations (413, or 69.3%) said that they supported people who were marginalised; 345 organisations (57.9%) supported people who were financially at risk; 275 organisations (46.1%) supported people who were not shielding but who were nevertheless at risk from COVID-19; while 238 organisations (39.9%) supported people who were shielding. A smaller number of organisations (105 organisations, 17.6%) supported people who had COVID-19 symptoms or lived with someone who had symptoms.

Less than a third of organisations (155 organisations, 26.0%) also indicated they offered support to other groups. Such groups included, but were not limited to, people with ADHD, young people, older people, disabled people and carers.

3.3 Impact of the TSRF funding

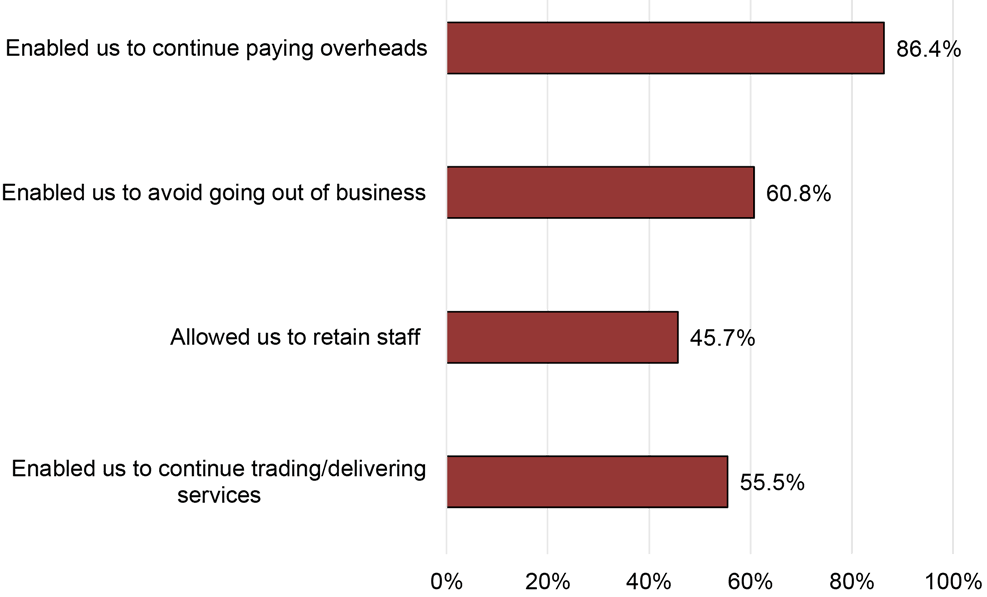

As part of the monitoring forms, organisations were asked about the impact of the TSRF funding on their organisation. Based on 785 returns, this impact is summarised in Figure 18.[20]

Four hundred and seventy-seven (60.8%) organisations indicated that the funding had enabled them to avoid going out of business. Four hundred and thirty-six responses (55.5%) said the funding enabled them to continue trading and/or delivering services, while 359 (45.7%) said that the funding allowed them to retain staff who would otherwise have been laid off. The majority of responding organisations (678, or 86.4%) said that the funding had allowed them to continue paying overheads. It was clear from the responses to this question that the fund had a real impact in supporting organisations to remain open, to continue to employ staff and to deliver essential services.

3.3.1 Helping to cover essential costs

The TSRF grant enabled many organisations to survive during the first period of full lockdown in March 2020. Many organisations were entirely dependent on regular trading and other income streams which had to be halted as the delivery of face-to-face services or fundraising activities became impossible. Despite the reductions in their usual income streams, many organisations – especially as needs became more acute as a result of the pandemic – sought to retain or even to increase their service delivery – or simply to retain their premises and future operating capacity – requiring the ongoing payment of overheads and staff costs.

In the monitoring form, organisations were given the opportunity to provide open comments in relation to the fund, and many used this space to explain these difficulties in detail. These responses particularly showed how the TSRF awards had helped organisations in need:

“The monies which we received from the Third Sector Resilience Fund, without a shadow of a doubt, allowed the charity to continue during the COVID-19 restrictions. Without this money we would have had to make all staff redundant at a minimum and perhaps even close the charity.”

“[The] Third Sector Resilience Fund was a real help for us to pay off our office rent for [four] months and telephone & broadband bills for three months.”

The TSRF largely helped to cover necessary costs for organisations that were left unable to earn an income during lockdown. However, organisations also expressed worries that, as TSRF funding came to an end, they might struggle to cover essential costs in the future, especially if further COVID-19 restrictions were introduced. (As noted previously, the majority of monitoring forms (79%) were submitted by organisations between June and September 2020, before further COVID-19 restrictions were re-introduced towards the end of the year.)

3.3.2 Staffing levels

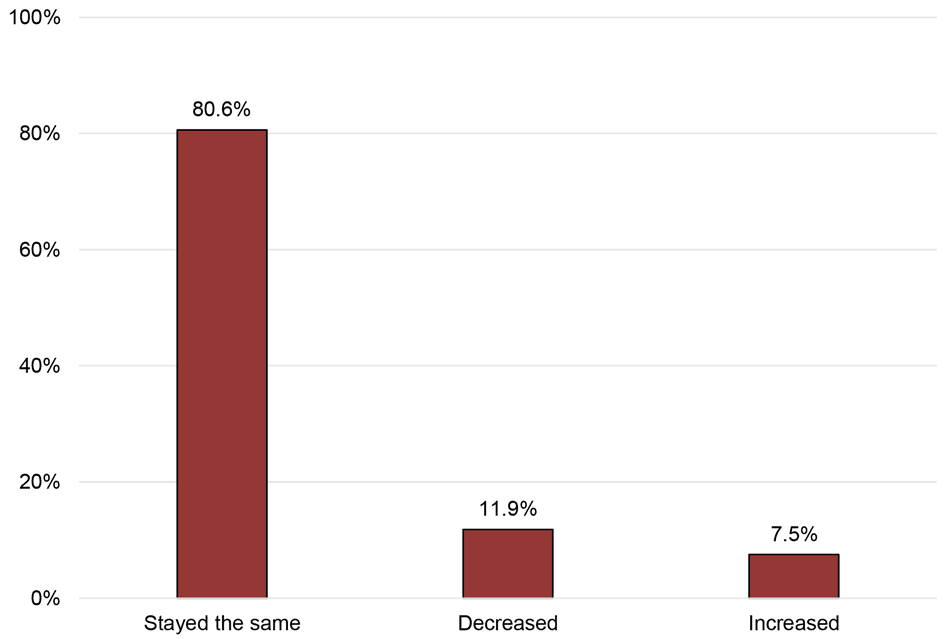

Organisations were asked whether their staffing levels had changed since receiving TSRF funding. As shown in Figure 19, of the 774 returns providing an answer to this question, the vast majority (624 organisations, 80.6%) were from organisations which said that their staffing level had stayed the same. Ninety-two forms (11.9%) were from organisations which said their staffing levels had decreased, while 58 (7.5%) were from organisations which said their staffing levels had increased. As such, the data indicate that most organisations receiving the funding had been able to protect staff positions.

A number of organisations said that without the TSRF funding, their only alternative to closure would have been a reduction of services and, quite likely, redundancies. Some respondents said that they would have already closed completely if it was not for the TSRF funding, but some also added that once the grant ended, closure was still a likely outcome.

Several respondents mentioned other sources of funding they had received which also played a large role; this suggests that the TSRF was perhaps most effective when used alongside other funding schemes. In particular, the furlough scheme and the TSRF together seemed an effective combination, allowing organisations to maintain their staff and to retain them after the end of furlough.

“Because of this grant helping with overhead and operating costs, our organisation has been able to divert its funds to maintain staff and continue to operate and deliver important services despite COVID-19.”

“This funding probably saved the organisation. We were very close to having to make everyone redundant by mid-May [2020] before receiving emergency COVID-19 support.”

Unfortunately, a small number of organisations reported having to let staff go due to not having the funds to continue to employ them. Some organisations expressed that without the TSRF they would have had to make staff redundant sooner. Others said that once the furlough scheme ended, they would have to make furloughed staff redundant due to financial constraints.

3.3.3 Service users

Beyond the organisations, staff and volunteers that benefited from the TSRF, the Fund also had a significant impact for the service users engaging with organisations in receipt of funding. A number of organisations stressed the importance of their work in local communities – in particular, those organisations providing essential services to the isolated and vulnerable, and those providing mental health related services.

“This, and other Scottish Government and independent emergency funding has enabled us to continue supporting our already vulnerable service users at this time.”

“We provide a lot of help either physically to local people in our area, who are not able to clean and shop for themselves as well as being at the end of the phone for many lonely and vulnerable people <…> Financially the [TSRF] grant was very instrumental in getting us through the last five months.”

Organisations also noted that the process of becoming compliant with COVID-19 regulations and providing extra safety measures had created additional costs. Despite the measures taken, several organisations also stated that some of their service users were reluctant to return as they were still shielding, or were simply not confident that it was safe to return to face-to-face interactions.

3.3.4 Adapting and diversifying services

For many organisations, the pandemic created an increased demand for their services at a time when their capacity was drastically reduced. The costs involved in adapting services to be delivered remotely, or resumed in a safe and compliant manner, were considerable. That being said, several respondents noted how the TSRF helped them to adapt and diversify their service delivery quickly and to continue operating even during the height of restrictions.

“The funding we received enabled us to respond rapidly and redesign our service delivery model in lockdown. It helped us increase our capacity to offer crisis support to both existing and new clients.”

The TSRF also helped organisations to address the increased demand for their services. The services that were reported as being the most in demand included food provision and mental health services. At the same time that this demand increased, capacity decreased, and this created a backlog of need for services which may have been difficult for many organisations to handle even once the restrictions were lifted.

The TSRF helped some organisations to prepare for this backlog and to develop new and expanded forms of service delivery. In some cases, businesses were able to use the funds to help respond to the crisis by adapting their services and enabling them to be provided virtually. Some organisations even said that the move towards virtual service provision helped to improve their services overall, as it removed certain barriers to accessibility and created the potential to reach more people going forward. Organisations wholly dependent on face-to-face services struggled to adapt their services to a new remote environment.

“This new service delivery model was essential to us being able to continue to support our client group. As well as fulfilling this purpose it has also brought additional benefits like removing geographic boundaries to our service and broadening our reach.”

3.3.5 Preserving cash reserves and supporting financial resilience

Another common concern for many organisations was that of restricted funds. Many said that although their current cash balance may have looked relatively healthy, in practice they were not able to use reserved funds. Typically, these were funds that were designated for use on contracted projects which were unable to proceed due to the pandemic.

Other organisations had considerable reserves in place but were unwilling to spend these due to concerns about the level of uncertainty ahead and because they wanted to ensure that essential work would be able to continue. Therefore, in several cases, the TSRF grant helped organisations to preserve their essential cash reserves by covering unexpected costs, allowing some organisations to maintain a degree of preparedness for the future.

Unfortunately, other organisations did not fare as well. Some stated that not only had they lost all of their income, but that they had also exhausted most of their reserves. A number stated that they were still unsure if their organisation would survive. Some stressed that they would have already closed completely were it not for the TSRF, although some also added that closure was still a likely outcome once the grant ended.

“We have no reserves. We will be able to use some of the restricted money in August for a commissioned piece of work towards staff pay, but we need more funding by September [2020].”

The open text questions from the monitoring form also show that organisations tried hard to avoid exhausting their cash reserves and going into debt. Being able to use the TSRF grant to cover essential costs, such as rent and utilities and, in some cases, continuing with loan repayments, allowed organisations to maintain essential cash reserves to support programme delivery or other important projects. This reflects the intended purpose of the Fund, which was to enable organisations to emerge from COVID-19 in as strong a position as possible, reducing the extent to which they were forced to take actions that would risk undermining their financial viability or long-term survival.

A number of stakeholder interviewees also had concerns about organisations that had large reserves potentially missing out on TSRF funding because of these large reserves. Organisations with large, restricted reserves may have been unable to access their reserves, but would not have necessarily qualified for TSRF.

Interviewees also mentioned that some organisations that were ineligible for TSRF due to large reserves ended up using the reserves to stay afloat; these organisations became weaker financially in comparison with organisations which had smaller reserves but which received TSRF funding. It was acknowledged that TSRF criteria around reserves was introduced to make sure that only those organisations which were most in need would receive funding, but some interviewees questioned whether this was the best way to determine need.

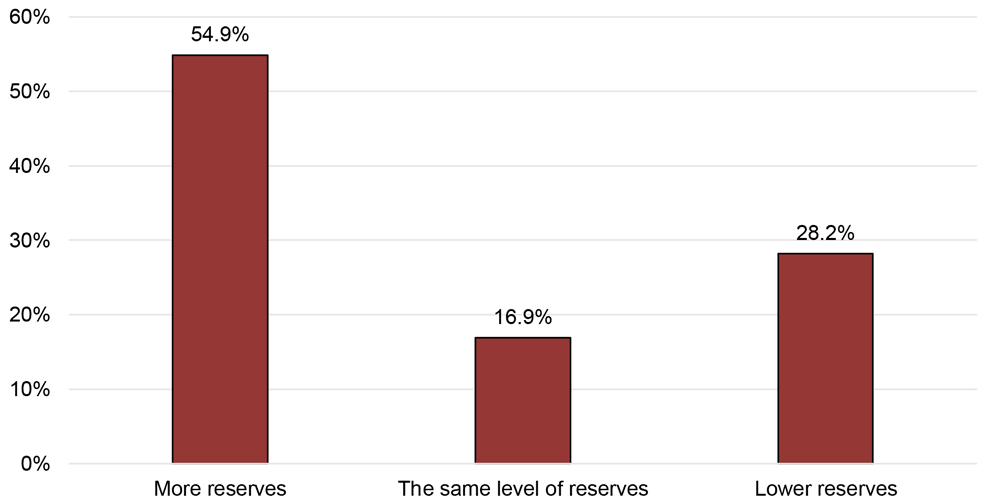

All organisations that applied for the TSRF were asked about their current unrestricted reserves (asked during first round of applications) or their reserves (asked during second and third round of applications). Organisations were again asked about their current reserves when filling out the monitoring forms. Figure 20 summarises the responses among the 727 monitoring forms providing information about current reserves.

As the graph shows, 399 organisations (54.9%) had more reserves at the end point of the funding period than they did when they applied for a TSRF grant. One hundred and twenty-three organisations (16.9%) had the same amount of reserves and 205 organisations (28.2%) had lower reserves.

That 54.9% of organisations reported having more reserves at the end of the TSRF than when they did at the point of applying to the Fund cannot be solely attributed to the TSRF. It is likely that many of the organisations supported through the TSRF were also in receipt of support from other sources, including the UK Government furlough scheme. In addition, the required slowdown in operational activity for some organisations may have improved their reserves position in the short term. However, the data do suggest that the package of support measures in place did support a degree of financial resilience and enabled many organisations to maintain their readiness to restart their work as soon as restrictions would allow.

3.3.6 Future uncertainty

Despite the various positive impacts of the TSRF, at the end of the funding period, many organisations still struggled and their futures remained uncertain. There were obvious limitations to the TSRF – in particular, the fact that the Fund was only intended as a short-term solution while businesses were unable to generate their own income, and at the point when the Fund was put in place, it was impossible to predict the length of the pandemic and the impact that it would have.

There was a sense that the pandemic lasted much longer than anticipated and, at the time of filling out the monitoring forms, the prospect of a second lockdown weighed heavily on many organisations. Though grateful for the funding, most conceded that unless they were able to resume their regular activities and income generation, they would not be able to survive in the longer term.

“We are still in an unknown phase at the moment as the majority of our normal passenger transport services are suspended due to the [fact that the] majority of passengers we provide transport for are in the vulnerable category. Therefore, long-term financial sustainability is an on-going concern.”

As one organisation pointed out, while the TSRF helped to keep the organisation afloat, they were ultimately saved by the fact that they were able to reopen in September 2020. A lot of organisations could not be confident about surviving until they could reopen and resume trading/generating income. This is even clearer in the accounts written from the perspective of organisations that were still unable to reopen at the time of completing the monitoring forms. For them, the future was often bleak and uncertain. As essential as the TSRF had proven to be, crucially, the funding could not replace their regular income.

“Since the easing of lockdown restrictions some of our social enterprise ventures (our source of generating unrestricted funds) have been able to recommence, however the income generated so far is well below pre-COVID amounts and this will pose major issues for funding our core costs going forward.”

“We have no income until next April [2021] and we are currently living on our bank loan <…> We are having to increase our product and service costs to take into account the additional costs of COVID-friendly working.”

3.3.7 Organisations’ likelihood of remaining operational

When completing the monitoring forms, organisations were asked if their organisation was still operational at that point in time. Of the 786 organisations providing an answer to this question, 773 (98.5%) said that they were still in operation, while the remaining 12 (1.5%) said that they were not.

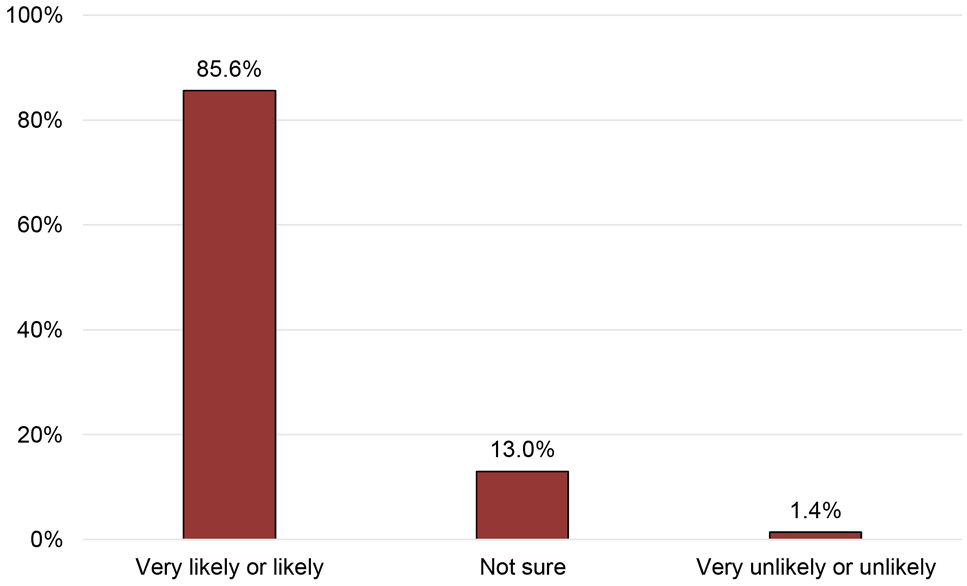

Organisations were also asked how likely it was that they would still be operational in six months’ time. Figure 21 shows that, of the 769 responses received, the majority of organisations (658, 85.6%) said that it was very likely or likely that their organisation would be operational in six months’ time, with only 11 organisations (1.4%) saying they were unlikely or very unlikely to be operational. The remaining 100 organisations (13.0%) were not sure.

3.3.8 Longer-term impact of COVID-19

Organisations working in certain sectors some faced particular challenges at the point when the monitoring data were collected. For example, businesses dependent on tourism were particularly worried about the future. Respondents from these businesses stressed that, while the TSRF had helped to sustain them during lockdown, they still lost several months of essential income during the spring/summer season which would usually have sustained them for the rest of the year. Being able to re-open would not immediately result in generating income if the work was largely seasonal. For many it would not be until regulations were relaxed that they could have any hope of recovering.

“Our main source of income is generated during the summer months when our [organisation] is open. This income has been severely restricted and without grant aid the club would not have been able to continue. We have opened our [organisation], subject to Government restrictions, to allow our member to gain access and exercise. This however led to increase costs in respect of the additional hygiene facilities needed.”

Organisations reflected on other potential long-term impacts of the pandemic. Though many organisations had adapted their service delivery approaches to ensure safety and to remain in line with COVID restrictions, they understood that any return to normality would likely be very slow. Organisations felt that many service users, particularly older and vulnerable people, would be hesitant to return to face-to-face activities even after regulations allowed it.

“We are hopeful but also very aware this virus has not gone away and given that our membership is made up of the most vulnerable people in the community it is very difficult to forecast when we may return to normal operation.”

3.3.9 Conclusions

Overall, a majority of respondents expressed appreciation for the funds received through the TSRF. It provided a crucial lifeline for many organisations, though some respondents said they did not receive as large a grant as they had hoped for. The longevity of the scheme was the biggest concern for some respondents, who felt that their organisation would be in a precarious position once the temporary funding ran out. In particular, the prospect of a second lockdown left many feeling that, unless another round of funding was offered, they would still struggle going forward.

“This small fund was essential for us as it allowed us the time to apply for other funding and therefore kept us in business. Thank you!”

“Thanks to this funding we have remained a viable organisation, thank you for your support. It has made all the difference.”

Contact

Email: socialresearch@gov.scot

There is a problem

Thanks for your feedback