Green Heat Finance Taskforce: report part 1 - November 2023

The independent Green Heat Finance Taskforce, has identified a suite of options which will allow individual property owners to access finance to cover the upfront costs for replacing polluting heating with clean heat solutions in the manner best suited to their own individual circumstances.

3. Strategic Context and Background

3.1 Characteristics of Scotland’s domestic and non-domestic buildings

There are over 2.5 million domestic properties in Scotland, with almost 1.6 million being owner occupied homes, over 360,000 in the private rented sector, and nearly 580,000 which are social housing. Over 1.3 million of these properties have an EPC energy efficiency rating of C or better, while around 325,000 have EPC ratings of E or lower. Social housing as a sector, though, does have a better overall energy efficiency rating than that of other domestic property types, 65% of social housing having an EPC rating of C or better, compared to 52% for all domestic buildings.

Mains gas remains the principal source of heating for the vast majority of domestic properties, with 81% of homes heated by gas, compared to just 11% for the electricity, which is the second most popular source, followed by smaller contributions from sources like oil or communal heating.

The predominance of gas as a primary heating source highlights the scale of challenge involved with converting the existing building stock to ZDEH, the cost of which is estimated as in excess of £22 billion, with a further £5 billion required to support energy efficiency upgrades. The overall costs estimates are aggregated across all property types, and will, therefore, mask the variation that will exist between individual properties, where factors like property age, size and location all have an influence on both the most appropriate technical solutions and the costs.

The number of non-domestic buildings in Scotland is much smaller, being around 230,000. They are, however, of varying sizes, from very small (public toilets for example) to very large (hospitals) and the data available on their current energy efficiency levels and typical costs for retrofitting individual properties is limited. Indications are, though, that energy efficiency is very poor across non-domestic buildings with 85% of those with an EPC rated as D or lower.

We do, however, know though that the majority of non-domestic properties are heated by electricity (59%) suggesting that improvements in energy efficiency are at least as important as converting to ZDEH as a way to maximise non-domestic buildings’ contribution to Scotland’s Net Zero goals. As the total floor space varies across (and within) sectors – while the sectors with the greatest floor space do not necessarily align with the sectors that have the most properties – there are a range of challenges for policy makers to wrestle with when planning how best to encourage action to convert non-domestic properties to ZDEH and to undertake relevant energy efficiency retrofitting work.

Annex 3 provides a more detailed discussion of the characteristics of the current domestic and non-domestic building stock from a heating perspective, based on the data available.

3.2 Policy Context

In 2019 Scotland declared a Climate Emergency and enacted the Climate Change (Emissions Reduction Targets) (Scotland) Act 2019, committing Scotland to Net Zero emissions by 2045, with interim statutory targets of a 75% overall emissions reduction by 2030 and by 90% by 2040. The update to the Climate Change Plan, published in December 2020, committed to a reduction in emissions from both homes and non-domestic buildings of 68% by 2030 compared to 2020 levels[5].

The Scottish Government set out its plan for reducing emissions from homes and non-domestic buildings in its Heat in Buildings (HiB) Strategy including the role of different technologies such as heat pumps and heat networks. This strategy recognises that not all actions in support of emissions reductions in homes and buildings can be delivered by the Scottish Government alone, with some regulatory and policy levers remaining reserved to the UK Government. For example, the reformation of gas and electricity markets is needed, including with respect to current higher costs for electricity relative to gas, to align Net Zero emissions goals with ambitions to end the use of fossil fuels such as gas to heat buildings. Decisions on the future role of hydrogen and the gas network are also required at a UK level[6].

In the HiB Strategy the Scottish Government committed to:

- improve the energy efficiency of buildings, so as to reduce heat demand, and to remove fossil fuels heat generation by supporting renewable heat technologies, such as heat pumps, heat networks and hydro-electric technologies;

- work with local government to put in place Local Heat and Energy Efficiency Strategies (LHEES); and

- continue to provide stimulus to the heat and energy efficiency sector through £1.8 billion of funding and financing in the current Parliamentary session to:

- generate opportunities across Scotland through delivery programmes that will support local jobs and create opportunities for young people;

- expand work with the supply chain, including the co-creation with industry of a Supply Chain Delivery Plan; and

- bring forward Regulations setting standards for property owners across all tenures and building types.

Underpinning this national strategy is the development of LHEES, which will help to guide the rollout of measures, as well as inform the designation of heat network zones. All local authorities are legally required to produce a strategy for heat transition in their local catchment area by the end of 2023. These strategies will include how each segment of the building stock needs to be upgraded to meet national and local targets on ZDEH, as well as measures relating to the removal of poor energy efficiency as a driver of fuel poverty. Additionally, they will identify heat decarbonisation zones, highlighting the primary opportunities for emission reduction in each zone.

This Taskforce’s work has been focused on achieving a better understanding of the finance mechanisms that could support the retrofit of homes and buildings by helping individuals, businesses and organisations spread the upfront cost of installing energy efficiency measures and ZDEH systems. The Taskforce has also made recommendations that identify options that could help address some of the existing barriers to installing ZDEH. These barriers must be addressed alongside challenges within the financial sector itself to help ensure the continued growth in the range and scale of finance mechanisms necessary (picked up in more detail in Chapter 4).

However, while acknowledging that the Scottish Government has ambitious targets in place to reduce emissions from buildings, the Climate Change Committee is concerned that policies are not yet in place to support the rapid deployment of energy efficiency and low carbon heating necessary to be able to achieve these targets[7]. This situation could act as a break in the development of the market place as it may impact on demand generation. The Taskforce understands that the Scottish Government plans to introduce a Heat in Buildings Bill during the current Parliamentary session to help underpin and drive delivery of ZDEH. Alongside this, the Scottish Government is reviewing and developing proposals to reform Energy Performance Certificates[8]. The Taskforce considers these steps important aspects of creating a long-term and certain environment, helping to de-risk investment in the finance sector and allowing for new products to be brought to market.

The Taskforce will work with and feed into a range of existing collaborative fora that exist between the finance sector and the Scottish Government, including the Financial Services Growth and Development Board (FISGAD) and its sub-groups, as well as the Scottish Government’s Net Zero Investor Panel, which is co-chaired by the First Minister. The latter was established in December 2022 to advise on how Scotland can create the right conditions to attract global capital to develop the physical infrastructure required for a just transition to Net Zero[9]. There are common areas of interest for this Taskforce and the Panel, for example, considering how to attract capital at scale to support a just transition of Scotland’s buildings.

3.3 Green Heat Finance Taskforce

The Green Heat Finance Taskforce (GHFT) was established in February 2022, following a commitment in the HiB Strategy, with a remit to explore and report on:

- Alternative financing – setting out sources of funding and finance for heat decarbonisation, including for existing and new technologies to meet medium and longer term requirements.

- Market demonstrators – opportunities to pilot value-for-money and innovative financial mechanisms to unlock individual and community level investment.

- Ongoing engagement on financial products – catalysing constructive longer term relationships and partnerships between the public sector, the heat sector, industry, wider supply chains, building owners and financial institutions.

- Strategic alignment – support balancing the needs of heat decarbonisation with the requirements for private investment activity across the wider energy system to deliver broad socio-economic benefits.

This is in response to the significant funding and financing gaps that exist, and the challenge of attracting private investment into the heat in buildings transition. The estimated gross cost of achieving ZDEH, including energy efficiency improvements to reduce heat demand, are significant. The Scottish Government has estimated this as being in the region of £33 billion, based on prices in 2021[10]. Capital funding from the Scottish Government for heat and energy efficiency improvements over the current Parliamentary session to 2026, is £1.8 billion, including specific support for those least able to pay, as well as funding to support infrastructure development[11].

Bridging the financing gap between committed Scottish Government funding and the total financing required will be challenging. The right mix of measures, including market signals and delivery mechanisms, will need to be in place to help create customer demand for (and straightforward access to) ZDEH and energy efficiency measures, as well as help de-risk private investment and reduce the cost of finance. There will be a need to scale up and flex existing products, as well as innovate to develop new financial products to help spread the upfront costs of retrofitting homes and buildings.

The Scottish Government will need to strike the right balance between providing direct funding support and fostering increased private finance, and will, therefore, need to determine which segments of society and which building types need higher subsidy levels to make retrofit cost-effective and ensure the overall transition of heat in buildings is fair and just. In making these determinations the Scottish Government should look in particular at where and how the public funding available could be used to leverage additional private investment, and, therefore, increase the overall reach of the funding. How to effectively incentivise groups less able to draw on direct Scottish Government funding will also be vital to a successful transition to ZDEH.

The GHFT has been co-chaired by the Minister for Zero Carbon Buildings, Active Travel and Tenants Rights, alongside Sara Thiam, Chief Executive of SCDI[12]. This Part 1 Report primarily covers the Taskforce’s conclusions around options to grow private sector financial support for individual building owners. It identifies the key barriers which currently constrain the provision and/or uptake of products to finance private investment in ZDEH solutions, and enhancing the energy efficiency of buildings. It considers both domestic and non-domestic buildings, with Annex 2 outlining the range of existing financing being provided by the Scottish Government.

A range of mechanisms will be required to allow people to access the option which is most appropriate to their individual circumstances, and we expect individual and communal approaches to work in tandem. The Taskforce’s Part 2 Report will therefore cover financing of communal approaches to both ZDEH generation and energy efficiency, taking into account options for social housing, area-based approaches and heat networks. These mechanisms are largely focussed on larger scale financing, such as regional and neighbourhood financing of Net Zero improvements across multiple buildings, and should provide alternative mechanisms that complement financing which may be secured by individual building owners.

3.4 Key Themes

To foster an effective and efficient green finance market capable of funding the transition to ZDEH with associated energy efficiency improvements, we have identified three key themes impacting on financing and which are aligned with and support the needs articulated by the HiB Strategy. These themes are –

- Market pillars – recognise the flow of finance needs to be considered holistically and is dependent upon sufficient demand, as finance is one of many inter-linking factors that give providers confidence to offer finance and customers assurance they are making the best decision for their circumstances.

- Regulations – which, alongside incentives to encourage actions, can have a positive impact by providing clarity around future building requirements and give confidence for providers to invest in products and skills.

- Co-investment – acknowledges the potential benefits from being able to pool funding, share expertise and de-risk potential private investment, thus delivering more in partnership than any one party can do individually.

Figure 3‑ 1 Key underpinning themes to support effective market in green financial products

Regulations

1. Expand regulatory coverage

Regulations for decarbonisation are present in certain sectors, needs to be expanded to owner occupier market to signal change to market.

Co-investment

3. Leverage public sector subsidy

Use Scottish Government financial resource to de-risk early market development for private sector, and, thereby, promote growth.

3.5 Market Pillars

Encouraging development of robust market pillars will create an overarching framework to both structure the market and grow the number of participants. While many of the features that could be considered market pillars are not explicitly financial, and are therefore not directly within the scope for this Taskforce, we argue that failure to consider these factors has implications for the ability of finance to flow effectively. Without aligning action to support key market pillars, there will be less demand for financing and a lower supply of private finance.

Figure 3‑2 Summary of key market pillars

Finance

Advice & Information

Good quality, independent support and information.Assessment

Create action plan of suitable measures to meet improvement targets.Quality Assurance

High standards of quality, customer care, competence, skills and training, and health and safety.Consumer Protection

Safeguarding customers against unfair practices in the marketplace.Monitoring & Evaluation

Evaluate progress against aims and objectives to support ongoing policy development.Branding, Marketing & Comms

Raise awareness and motivate occupiers to undertake improvements.Delivery Mechanisms

Different routes to market for decarbonisation measures, e.g. LHEES, Heat Networks.Skills & Supply Chain

High training standards and installers are suitably qualified.

The above diagram summarises important wider factors to consider. These are –

- Advice and information – good quality, independent advice and support can help people navigate a complex landscape.

- Assessment support – helping people develop and follow an action plan that is appropriate to their circumstances and helps meet wider heating targets.

- Quality assurance – consistently high and standardised levels of products, customer service, skills and reporting to provide certainty on quality of goods and services (for both customers and finance providers).

- Consumer protection – safeguarding customers against unfair practices in the market place and ensuring effective right to redress where unsatisfactory advice or services have been provided.

- Monitoring and evaluation – tracking progress and impact of initiatives with timely data and evidence to create effective feedback loops.

- Marketing and communications – to raise the profile of available products and services, including the features and benefits for different parties.

- Delivery mechanisms – routes to market and to delivery of measures, recognising a range of options exist across different types of buildings and/or ownership structures, for example, Heat Networks or LHEES.

- Skills and supply chain – having an appropriately trained workforce and sufficient capacity within supply chains to deliver the physical improvement works.

Annex 5 provides more information of market pillars and what the Scottish Government is doing to develop them.

3.6 Regulations

Effective regulation can support stimulating the market for energy efficiency and ZDEH by influencing the demand for retrofitting measures and their accompanying need for finance. Regulations can also support supply side confidence to develop financing products, as well as encourage investment in the necessary skills and training for employees to meet an increased demand for retrofitting work.

Regulations can help boost the demand for financing products to fund energy efficiency and ZDEH improvements by clearly setting out the requirements which have to be met for different building tenures and the timeframes which they need to be achieved by. Evidence indicates that purely voluntary approaches to encouraging energy efficiency and ZDEH retrofit will not deliver the scale of transformation required, even with generous grants available. For example only 1% of forecast demand for UK Green Deal financing was actually provided to consumers. Even allowing for design flaws with the products offered, the level of take-up for such a voluntary scheme was extremely low[13].

As well as boosting the demand for ZDEH and energy efficiency, regulations can boost the supply of finance by providing a clear and strong signal to the market about policy intentions. This can provide confidence to the market, stimulating the development of new products, as there is greater certainty of future demand. It will also support growth and investment in market pillars such as skills development and the building of supply chain capacity, as the wider market responds to the clarity about future conditions and demand.

The Scottish Government is taking forward work on regulation and is committed to consulting on a proposed Heat in Buildings Bill in the coming year. While this Taskforce has not considered the issue of regulation in detail, we do believe that appropriate regulation will be an important part of the overall structure required to deliver against the Scottish Government ambitions to decarbonise homes. Regulations will need to be carefully developed and be cognisant of a Just Transition, to avoid being regressive and placing an undue burden on those least able to pay.

3.7 Co-Investment

Co-investment, also known as blended finance, is a financial structuring approach which combines finance and other resources from a range of sources with different risk tolerances for use on agreed shared priorities. Many forms of blended finance structures are currently either in use or under discussion. In general, these financial structures combine capital from public (or philanthropic) sources to help overcome the for private investors or lenders[14].

There is a strong case for government intervention and support to spur innovation and lead by example, particularly in the short term. This will help to support market creation and maturation as government can foster an attractive investment environment. As private investors, even patient investors such as pensions funds, are investing clients’ money and they have to comply with the legal and fiduciary responsibilities established by regulators. This requires longer term confidence in systems and risk profiles to enable finance to flow.

In some instances, this may require blending approaches that have comparatively high portions of public to private finance, at least initially. As noted by Professor Mazzucato in her proposition for a mission-orientated frame for the Scottish National Investment Bank:

“Missions by nature are designed to spur innovation towards addressing societal challenges. But because innovation is highly uncertain, has long lead times, is collective and cumulative, it requires a specific type of finance […] Early stage public investment helps to create and shape new markets, nurturing new landscapes which the private sector can develop further.”[15]

In blended structures, public sector funds can reduce risk exposure for co-financing partners by absorbing part or all the partners’ exposure to risks of missed repayments, default by borrowers or other forms of losses. In some instances, grants to support project development may be paired with pre-arranged private debt or equity. In other cases, public or philanthropic and private capital may be pooled together in a fund with different tranches of capital, accepting different levels of risk weight returns or different repayment priorities in case of default. Public commercial capital can also be deployed with a different risk appetite, or on a more patient basis than typical private lending or investment. Finally, public guarantees or insurance products may be issued to ‘credit enhance’ transactions or reduce the exposure of private investors to default and other risks.

An advantage of these approaches is that it can ‘crowd-in’ additional private sector funding, as the different tolerances for loss and return requirements between private capital and public grants or sub-commercial loans enables the blended approach to work. This can also mean lower repayment costs for individuals than if the funding was provided through solely private channels, or the ability to borrow more and still ensure repayments were affordable. It therefore has the potential to create significant scale by bringing a number of finance providers together, including longer term investors such as pension funds and insurers, to create a larger pool of finance, allowing the sharing of expertise and splitting of risk.

There is a range of co-investment mechanisms that could work in the ZDEH market, targeted at either an individual property level or at communal solutions. Similarly there is a range of options for investment vehicles that could manage Scottish Government interests. A number of forms of blended finance are already in use internationally to support energy efficiency and ZDEH investment.

The Scottish Government is already providing both grant and subsidised lending, combined with advice for households and SMEs (detailed in Annex 2). As illustrated in examples on pages 11-13, households are able to blend these individually with sources of private finance to fund the full costs of installations. However, examples from other governments show that this type of public funding can also support co-investment and blending at an overall level to reduce the overall costs to the public sector, while offering similar levels of public support to individuals.

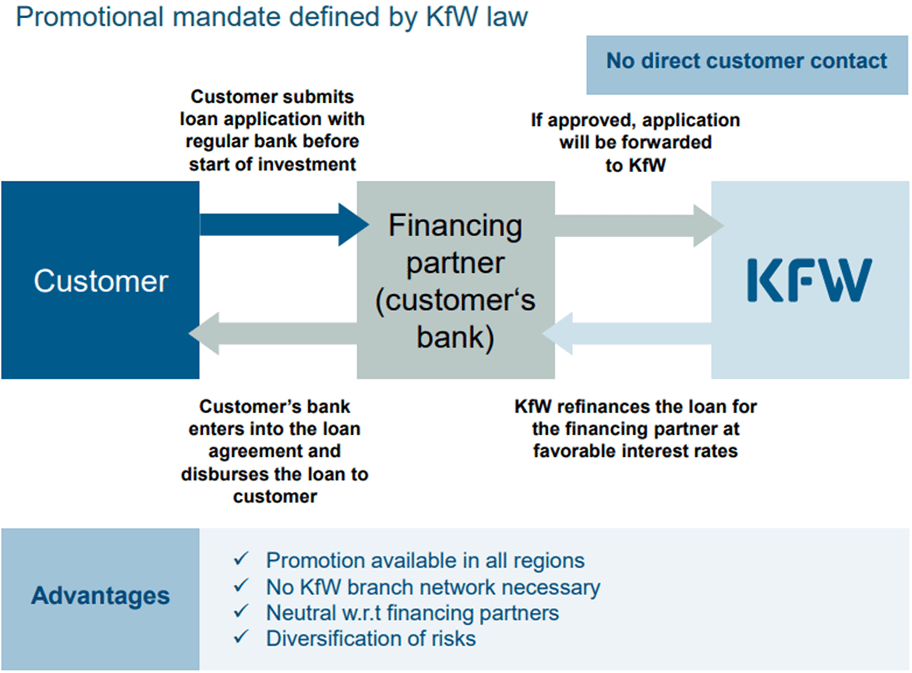

For example, Box 1 presents details of the German Government’s energy efficiency loan programme running since 2006 by KfW Development Bank.

Box 1: Example of Germany’s Energy Efficient Construction and Rehabilitation Programme.

Launched in 2006, Germany’s Energy Efficient Construction and Rehabilitation Programme combines limited grants from the German national budget with repayable concessional loans to households. Structured in a manner that incentivises ambitious renovations that meet the highest levels of national performance standards, the German Government provides performance-based grants of up to a maximum percentage of total project cost. The loans application and contracting process is managed by partner retail banks, which are then refinanced for the amount of the loan at concessional rates by KfW, Germany’s state owned development bank, which is committed to improving economic, social and environmental conditions across the world.

KfW raises most of its finance through international capital markets, issuing bonds which are guaranteed by the German state. While it is not allowed to compete with retail banks, as its state guarantees enable it to offer lower levels of interest, it can facilitate business in areas that fall within its defined mandate, for example, improving the environmental sustainability of homes.

As seen in figure below, customers apply for a loan through a participating retail bank, which manages the approval process. If approved, the partner bank notifies the KfW, which refinances the loan for the bank. KfW refinances these loans at a favourable interest rate which is passed on in part to the final customer. KfW is able to provide a concessional rate using limited public subsidies due to its ability to raise debt on the capital markets at comparatively low rates. KfW is, in turn, able to repay the debt raised on international capital markets by means of the repayment of loans by customers.

As the on-lending banks take on the credit risk of the final customers, they need to understand the programme conditions, including the technical aspects, so as to adjust their systems and information materials to reflect any changes. KfW also appoints special liaison officers for the partner banks and offer regular training on relevant issues for staff of the on-lending banks.

As a result, the programme is able to blend private investment from the international capital markets as well as the resources and existing networks of participating commercial banks, using limited direct resources from the German national budget. This has been estimated to deliver up to a 1:10 leverage ratio of public subsidy to loans and private investment (Hohne et al., 2009)[16].

Co-investment is a well-developed concept in Scotland and has been applied in areas such as funding City Region Deals or for funding of the UK Catapult Network of innovation and research centres. The development of co-investment vehicles will almost certainly need to play a part in financing the scale of heat transformation necessary. Co-investment mechanisms offer the potential to be combined with private sector products such as green mortgages or Property Linked Finance, which are discussed later in this report (see section 5.1). They could also be used to unlock investment in area-based schemes and potentially social housing, topics which will be the focus of our Part 2 Report next year.

Scotland has organisations with expertise in investment, such as the Scottish National Investment Bank and Scottish Futures Trust, which understand the nuances around co-investment, including the characteristics to be considered in structuring appropriate vehicles for investment. Taskforce members, including Scottish Financial Enterprise, are also well placed to facilitate connections with experienced private sector investors which will have direct knowledge of structuring blended investment mechanisms in other contexts, including managing the risk profile for different parties.

Contact

There is a problem

Thanks for your feedback