Safeguarding workers on temporary migration programmes: study

This study "An Immigration Option For Scotland? " considers the risks of exploitation to workers on temporary migration programmes. It looks at options for the Scottish Government to respond to these risks including reviewing the Open Work Permit for Vulnerable Workers established in Canada.

Canada’s Open Work Permit for Vulnerable Workers

In 2018, as the BC pilot was coming to an end, the Government of Canada proposed a new federal open work permit for migrant workers and their family members where there are “reasonable grounds” to believe the worker is at risk of or experiencing abuse (Government of Canada 2018). The Government of Canada’s proposal for an OWPVW recognised that the employer and sector-specific work permit creates a “power imbalance” between temporary foreign workers in Canada and the employer named on their work permit which increases risk of abuse (Ibid). The government conducted a wide-ranging consultation with key stakeholders - migrant worker support organisations, employers, trade unions, academics, industry and lawyers – on the design of the OWPVW (Aziz 2022). The proposal was accompanied by a financial commitment of C$194.1 million over five years and C$33.19 million per year ongoing to support a “robust compliance regime”, including unannounced inspections under the TFWP (Government of Canada 2018). An additional C$3.4 million was allocated to a Migrant Worker Support Network (MWSN) of support organisations, employers and frontline agencies, to support migrant workers to understand and exercise their rights in Canada (ESDC 2018). The OWPVW was implemented in June 2019, three and a half years on this Report will consider the effect of the policy on workers and its transferability to Scotland.

The following section will consider key issues identified in implementation of the OWPVW to consider before any policy transfer might be made. This analysis is used to develop an understanding of whether the OWPVW is a potential replicable policy option for Scotland. This section draws on interview data conducted with key stakeholders offering support to workers and engaging with the OWPVW. Firstly, it will consider which factors were key to the OWPVW design including learning from the BC pilot. Next it will look at how the OWPVW has been implemented: its application process and the consideration of applications and determinations. Finally, it will consider the impact of the programme on incidences of abuse, abused workers, and on the migrant support sector more widely.

1. OWPVW Design

The OWPVW is based largely on the BC pilot for temporary foreign workers at risk. Its design draws on learning from that pilot and incorporates the views of a wide range of stakeholders through consultations. The objectives of the OWPVW are like those of the BC pilot, to protect workers from abuse and to facilitate workplace inspections, however the definition of abuse differs as it relates to federal rather than provincial regulations. The following section will explore key elements of the OWPVW design along with some of the critiques raised and remedies presented.

The OWPVW was introduced by amendment to the Immigration and Refugee Protection Regulations [SOR/2019-148], provided for in the Immigration and Refugee Protection Act [S.C. 2001, c. 27 / subsection 5(1)]. The regulations entered into force on 4 June 2019 and provided for a work permit that is exempt from Canada’s LMIA process and which applies to all migrant workers on employer and sector-specific work permits, for whom there are “reasonable grounds to believe” that they are experiencing or at risk of experiencing abuse in their employment (IRCC 2022a). The OWPVW applies where migrants hold a valid employer or sector-specific work permit, or where migrant workers have previously held an employer or sector-specific work permit and have applied to renew that permit, regardless of whether a worker has previously engaged in unauthorised work in Canada (Ibid). An open work permit may also be issued to the family member of a worker who is found to be eligible for an OWPVW. Those applying for the OWPVW are exempt from normal work permit costs - the C$155 work permit processing fee and the C$100 open work permit privilege fee (IRCC 2022a). In addition, IRCC Officers are encouraged to exempt applying workers from a requirement to provide biometric information and pay the related C$85 fee for this service.

1.1 OWPVW influences from the BC pilot

The Government of Canada drew heavily on learning from the BC Pilot, set out above, for the design of the OWPVW, replicating the core principles of the permit, whilst also adjusting aspects that were felt to have caused problems in the pilot. Three design areas which were adjusted in the federal open work permit are the fees, the length of permit and the role of intermediaries in the application process. Whilst the BC pilot permitted IRCC officers to exercise their discretion over whether to charge application fees, all fees were removed for the OWPVW as were found to create a barrier to workers accessing the permit (Government of Canada 2019a). On the length of permit, while the BC open work permit was fixed at 180 days, the OWPVW regulations provide for IRCC officers to use their discretion to issue a work permit for up to 12 months. This draws on findings from the BC pilot where decisions took longer than expected and workers struggled to find alternative employment within the validity period of their open work permit (Government of BC). Finally, whilst the BC pilot required workers to submit a written recommendation from BC settlement service providers and a report of a complaint to enforcement agencies with their application, this element was removed from the OWPVW process. These three important design changes sought to broaden access to the OWPVW.

1.2 Objectives of the OWPVW

The objectives of the OWPVW are to ensure workers at risk of abuse can legally leave employers named on their work permit and to remove barriers to worker participation in employer inspections and cooperation with authorities.[4] These objectives seek to address the power imbalance identified for temporary foreign workers in Canada, by providing a route out of employer and sector-specific visas. They also seek to reduce the risk that workers will choose to leave abusive employment outside the terms of their visa. The objectives underline the importance of also addressing wider labour abuses and non-compliance in the labour market by facilitating the engagement of migrant workers in employer inspections and in enquiries by authorities, although the OWPVW is non-conditional on such engagement. Research participants were supportive of these objectives which span both specific and general risks to workers.

1.3 Link between the OWPVW and employer inspections

The link between a finding of worker abuse and compliance inspections serves as an important means of ensuring an open work permit for workers at risk of or experiencing abuse has a wider impact on cases of abuse and exploitation. Compliance oversight is divided in Canada between ESDC,[5] for workers on the TFWP and IRCC[6] in the case of workers on Canada’s IMP. As outlined above, at the point of introduction of the OWPVW, the Government of Canada dedicated greater resources to related compliance activity. When an IRCC officer issues an OWPVW, they share summary details with relevant IRCC or ESDC inspections and compliance branches (ARHW 2021). This referral of allegations does not automatically trigger an inspection, instead the employer in question is prioritised “within the existing envelope of compliance inspections planned each year” (Government of Canada 2019a). In addition, inspections seek to identify whether employers have made “reasonable efforts to provide a workplace that is free from abuse” rather than whether a workplace is abuse free (See IRPR SOR/2002-227). Whilst a finding of worker abuse is directly linked to workplace inspections, this does not guarantee a finding of non-compliance against their employer.

1.4 Definition of abuse

The OWPVW definition of abuse and cases of abuse reported to date by applicants for the work permit relate closely to situations experienced by workers on the UK SWV and therefore the definition provides a useful example for any potential transfer of this policy. The Immigration and Refugee Protection Regulations (IRPR), refer to five core categories of abuse, physical, sexual, psychological, financial abuse and reprisals.[7] The IRCC Programme Delivery Instructions set out guidance for the interpretation of abuse and examples of what workplace abuse could constitute for the purpose of the definition (IRCC 2022a). One analysis of OWPVW applications found the most common forms of abuse experienced were financial abuses, including excessive work hours, unpaid wages, recruitment fees and secondly, psychological abuses, including verbal abuse, threats of termination and deportation, physical abuse and sexual abuse was also reported in fewer cases (Aziz 2022 p.15). Since the implementation of the OWPVW, problems have been identified with the breadth of the definition of abuse, evidence required to meet the threshold of certain forms of abuse and IRCC Officer’s capacity to understand abuse which will be explored below.

One important area of discussion and development to the OWPVW definition of abuse is the issue of reprisals by employers against workers. Support organisations have reported cases where workers have had their employment terminated or where their work permit has deliberately been left to lapse in “retribution for complaining about working conditions” (Aziz 2022 p.19). However, in these cases IRCC officers have demonstrated patchy and poor understanding of the relationship between employer mistreatment and financial abuse (ibid). In addition, support organisations have found employers “allowing the work permit to lapse” (Hannah Deegan, ADDPD-ARHW) as a form of abuse, leaving workers undocumented and therefore ineligible for the OWPVW altogether. IRCC sought to avoid the OWPVW being used by migrants seeking to regularise their status in Canada, yet this lacuna poses a risk to workers who unknowingly become undocumented (Government of Canada 2019). In addition, the risks posed by data sharing means workers can be reluctant to apply where they have a previous failed immigration application or prior irregular status. In the 2022 update to the IRPR, ‘reprisals’ was added to the forms of abuse (196.2 (1) (e)) which goes part way towards bridging this gap in the definition.

One further area of concern by support organisations is the charging of illegal recruitment fees, which are included in the IRCC programme delivery instructions as abusive only if “based on false promises or misleading information” (IRCC 2022a). Some support organisations report IRCC officers are therefore determining recruitment fees not to constitute a form of abuse if they have been willingly paid for by workers (Aziz 2022). This is problematic as recruitment fees are both prohibited in domestic Canadian law and international law. A further amendment to the IRPR in 2022 sought to address this issue by prohibiting employers from charging or recovering fees, including fees relating to the LMIA, compliance or recruitment (IRCC 2022b).

Finally, whilst the OWPVW definition of abuse is based on the IRPR, and therefore provided for in federal law, abuses of provincial employment standards can be overlooked. This includes “contraventions of employment contracts” or “being assigned work that is contrary to the conditions of a worker’s work permit and employment contract” (Aziz 2022 p.16). IRCC officers have been found to apply an inconsistent approach to such cases which one support organisation attributes to gaps in their knowledge of “provincial employment, health and safety and human rights legislation” (ARHW 2021 p.12). IRCC has responded to such concerns by updating its training to improve IRCC officer understanding of working conditions (Véronique Tessier, RATTMAQ). However, this is an important consideration for Scotland, where employment law and industrial relations are reserved, yet agriculture is devolved, with the Scottish Agricultural Wages Board setting minimum wages and terms and conditions for agricultural workers in Scotland.

1.5 Summary

The OWPVW was designed to reduce the risk of abuse for migrant workers on employer and sector-specific work permits to address significant power imbalance identified for workers on the TFWP. Its objectives are clear and its design draws heavily on evidence from implementation of the BC Open Work Permit for Temporary Foreign Workers at Risk pilot. The OWPVW, like the BC Pilot, is linked to employer inspection activity, which is triggered when a work permit is approved which could result in a finding of employer non-compliance. Abuse for the purpose of the OWPVW takes five key forms, physical, sexual, psychological, financial and reprisals. This broad definition of abuse has been welcomed by support organisations, yet some gaps have arisen during implementation, and problems have been identified with the interpretation of abuse in practice. IRCC has acknowledged and sought to address some of these lacunae through amendments to the IRPR, enhanced guidance and training for IRCC officers. Discussions on and revisions of the OWPVW definition of abuse provide particularly useful lessons for any policy transfer, with specific issues related to the interaction between provincial and federal legislation holding relevance for Scotland.

1.6 Relevant considerations for any open work permit for vulnerable workers

Any open work permit for workers at risk of or experiencing abuse should:

- Be available to all workers, including undocumented workers, and their family members.

- Not draw on data related to migrant workers’ previous immigration applications, thereby placing workers who come forward to report abuse at risk of detention and deportation proceedings.

- Be based on a definition of abuse which is informed by international and national laws that safeguard workers and informed by evidence of working conditions for temporary migrant workers, and input from experts in law, worker, and victim support.

- Require a report to be shared with labour market enforcement authorities, triggering an automatic inspection of employers of workers issued an open work permit. Such inspections should seek evidence that proactive steps have been taken by employers to identify and address worker abuse.

- Establish detailed guidance to inform assessing officers, including continuing professional development, including on trauma informed practice and interpretations of abuse.

- Ensure an ongoing training programme is in place for implementing officers, in order to ensure uniformity of interpretation of abuse and application of the definition to individual cases.

2. OWPVW Implementation

The OWPVW implementation over the past three and a half years has been closely followed by support organisations helping workers to apply for the work permit. The below section will consider the means of applying for the OWPVW and consideration of applications by IRCC officers. It will look at the evidentiary burdens and considerations and the basis for decisions. Interviewees shared some concerns regarding this process, which is extremely resource intensive for support organisations and applicants alike. These will be explored in more detail below.

2.1 Application process

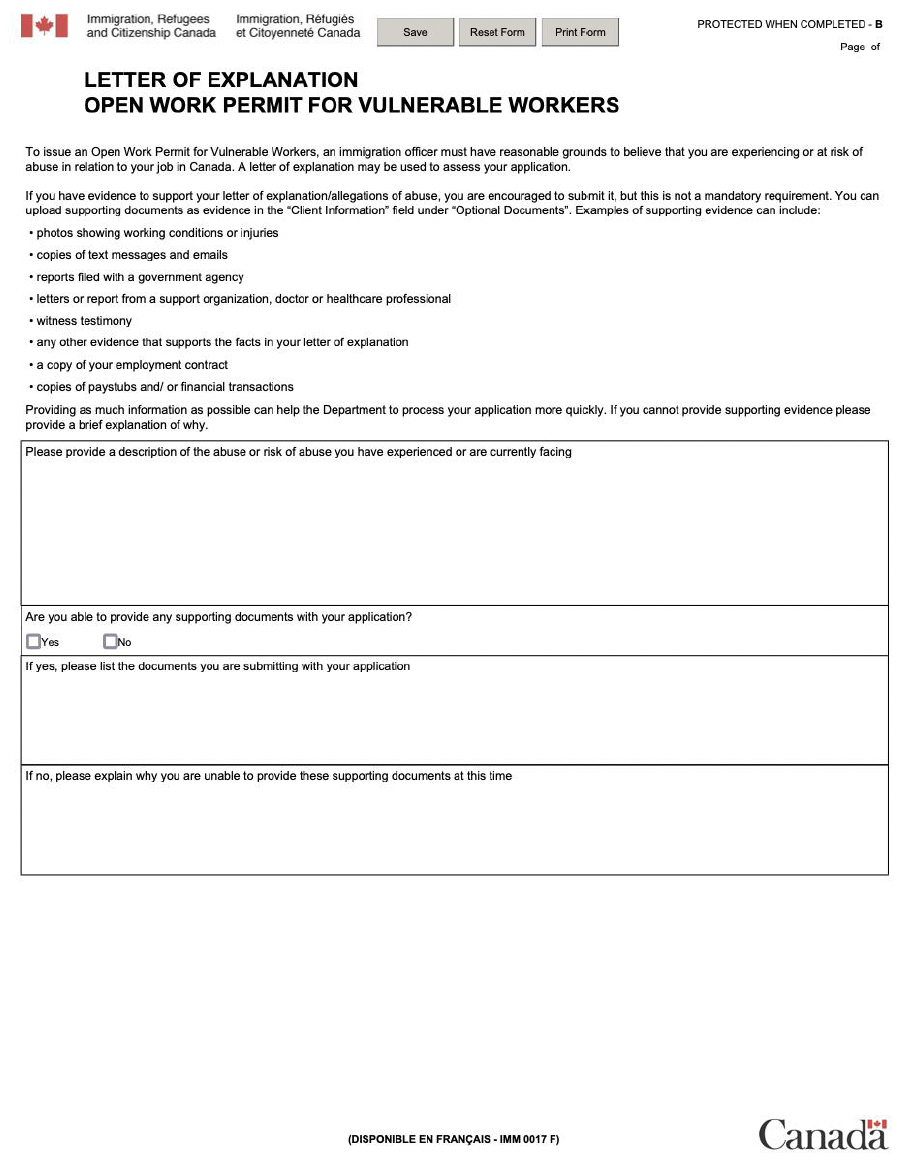

In a move to speed up the process, applications for the OWPVW are exclusively online, whereas during the BC Pilot, open work permit applications were paper based. Applications must be accompanied by a ‘letter of explanation’ describing the abuse or risk of abuse experienced by workers. This may be supported with evidence including photographs, digital communications, complaints to law enforcement, letters of support from frontline services, employment contract or payslips (see figure 2 IRCC 2022c). Once this information has been submitted then an IRCC Officer may use their discretion to decide whether to conduct an interview, in person or by telephone, with the worker to obtain further information.

Support organisations have found the OWPVW online application requires extensive additional information to achieve a successful outcome for workers. Two main concerns have been identified by support organisations with the OWPVW application process, the complexity of the online application and the evidentiary requirements of applicants. Many support organisations interviewed concluded that a successful OWPVW application is not possible without support.

2.2 Online application process

Support organisations find temporary migrant workers often lack the “technology or the literacy” (Delphine Nakache, University of Ottawa) to complete the online form and have limited understanding of “how the system functions” (Véronique Tessier, RATTMAQ). However, whilst some find the uniquely online form presents a technological barrier for workers, other support organisations find it speeds up the application process. Whilst information about the OWPVW is published in a range of languages, including Spanish, Cantonese, Hindi and Korean, the application form and supporting evidence can only be completed in English and French. One interviewee estimated that each application takes a support worker up to 30 hours (Véronique Tessier, RATTMAQ) and even more for the applicants. One interviewee reflected that the time requirement for an application “is not realistic for people working 60 hours per week” (Hannah Deegan, ADDPD-ARHW). The online application form has been found by support organisations to present a barrier to workers applying for the OWPVW without assistance. This creates a significant draw on the resources of support organisations which it is important to recognise and address.

2.3 Evidentiary requirements

As noted, applications should be accompanied by a range of evidence in order to be successful. As shown in figure 3, each application follows a two-step decision making process. In step one the evidence is assessed on a higher standard of proof, the “balance of probabilities”, or likelihood of it being true, then in step two the case as a whole is assessed and determined according to a lower bar of “reasonable grounds”, or more than a possibility (IRCC 2022a). A similar two-step process applies to the UK National Referral Mechanism (NRM) for potential victims of modern slavery/human trafficking in reverse order, first an initial reasonable grounds, “I suspect but cannot prove” assessment of the case is made to enable potential victims to access support services, then the case outcome, or ‘conclusive grounds’ decision, is determined on the balance of probabilities, which requires significant evidence gathering and review (CPS 2022). The review and pilot changes to the NRM provides useful evidence for establishing any similar system (Home Office 2017).

| Standards of proof (higher to lower) | Description | Officer's assessment |

|---|---|---|

| Beyond reasonable doubt | No doubt; convinced | Not applicable |

| Balance of probabilities | Likelihood of something being true | Step 1: Officers must be satisfied on a balance of probabilities (50 + 1%) that the facts and evidence provided by the migrant worker occurred and are credible.

|

| Reasonable grounds to believe | More than a mere possibility; would satisfy an ordinarily cautious and prudent person | Step 2: Officers must determine if they have reasonable grounds to believe that abuse occured or that there is a risk of abuse.

|

| Mere suspicion | Simply an emotional reaction that it might be possible | Not applicable |

Some support organisations find the evidentiary requirements to meet the balance of probabilities standard requires significant resources for data gathering and preparation (Aziz 2022 pp.20-21). In addition, whilst the OWPVW drew on learning from the BC pilot to eliminate the requirement for complaints to be submitted to enforcement agencies, some interviewees reported that applications are “more likely to be accepted if there has been a file of a complaint and a police report” (Hannah Deegan, ARHW). One interviewee said the evidentiary burden was high to account for IRCC officers being unable to contact a workers’ employer to get their view (Delphine Nakache, University of Ottawa). In some cases, support organisations have sourced application evidence by submitting freedom of information requests to government departments. This is viewed as an unnecessary step if this information can be obtained by the assessing officer instead. Some support organisations propose oral evidence gathering using “trauma informed human interface and interaction” (Amanda Aziz, MWC) as a simpler way to assess applications. Data sharing protocols, clarity around evidentiary requirements and standards and innovative means of gathering evidence could help limit the resource burden on applicants and support organisations.

2.4 Application processing times

A target has been set for IRCC Officers to make decisions on OWPVW applications urgently, within 5 business days from the time the application is received (IRCC 2022a). IRCC officers may use their discretion to decide on the duration an open permit, up to a period of 12 months. To ensure consistency in implementation, training is provided to IRCC officers on application assessment, including guidance on supporting evidence and eligibility. In addition, IRCC monitors decisions and cases to identify any changes that are needed to the guidance and delivery of the OWPVW (Ibid).

Whilst there is a requirement on IRCC officers to consider OWPVW applications urgently, in 2021 the average processing time was 40 days (ARHW 2021 p.16). For some workers, this means remaining with an abusive employer whilst their application is processed, therefore the longer an application takes to process the greater the risk to worker. Resourcing for IRCC capacity to process OWPVW applications relates to the estimation of applications that would be received, which was initially set at 500 annually (Government of Canada 2019b). However, data shows applications have in fact reached double this level requiring a re-think of resources allocated to the scheme (Aziz 2022 p.41). In its 2021 Budget the Government of Canada acknowledged the OWPVW processing problems and allocated C$6.3 million to IRCC over three years for “faster processing and improved service delivery of open work permits for vulnerable workers” (Government of Canada 2021 p.219). Interviewees supporting workers in different parts of Canada reported an improvement in decision making timeframes in 2022:

We’ve noticed in BC all of a sudden, literally in the last six weeks, we’ve seen five-day processing (Amanda Aziz, MWC).

However, some support organisations indicated that cases with greater complexity continue to take much longer than five days. Capacity to meet application processing time targets has been recognised by the Government of Canada as under resourced, it has allocated increased funding to meet a higher rate of applications than initially expected.

2.5 Worker interviews

Worker interviews can provide an opportunity to probe evidence and engage workers in a meaningful way yet can also serve as an obstacle to access if interviewers are not trauma informed. IRCC’s programme delivery instructions state that interviews should address “contradictions or gaps in the applicant’s submission” to add to the evidence provided (IRCC 2022a). However, some interviewees have found that IRCC officers can be reluctant to speak to workers, seeing a general drop in interviews since COVID-19:

If they have doubts about the admissibility of the worker they won’t search deeper, they won’t investigate, they will just refuse as that is problematic (Véronique Tessier, RATTMAQ).

Support organisations have raised concerns about the nature of interviews finding IRCC officers “insensitive to the workers and the trauma they experienced” (Aziz 2022 p.23). In response to such critiques, IRCC has developed further training for its officers which has resulted in more trauma-informed interviews (Amanda Aziz, MWC). Support organisations underline the importance of interviews being accessible to workers, including by ensuring interpretation is provided, workers are permitted to be accompanied by an advocate or support organisation, and the scheduled time and place is convenient (Aziz 2022 p.30, ARHW 2021 p.17). Worker interviews can serve as a positive way of gathering evidence if interviewing officers are trained in trauma informed practice and guided by an understanding of the complex needs of potential victims of abuse.

2.6 Length of permits issued

The length of work permits issued was increased based on findings from the BC pilot with IRCC officers exercising discretion to issue permits for 6-12 months. Whilst immigration officer discretion is a feature of the Canadian system, this does present a challenge to uniformity. In addition, many interviewees consider the 12-month validity of the OWPVW to be too short both logistically and emotionally for abused workers. Interviewees warned that the shorter the permit the more likely workers will re-enter dangerous tied employment situations, with one interviewee suggesting that to safeguard workers a “24-month period would be preferable” (Daniel Lee, Fasken). It is important that the length of work permits is based on the time it could take for workers to find secure employment and reviewed based on practice.

2.7 Decision making

Transparency over decision making and criteria is important, to facilitate uniformity and provide grounds for learning and review. Currently the OWPVW decision making process is not routinely published and support organisations access information about decisions through freedom of information requests (Véronique Tessier, RATTMAQ). Support organisations can draw on an officer’s rationale for a decision, to improve future applications and to re-apply for workers or contest refusal (ARHW 2021 p.35). There is no dedicated review process for the OWPVW, applicants instead pursue judicial review, request reconsideration or re-application (Ibid p.18). An integrated review process has not yet been considered by the Government of Canada, but could simplify reconsiderations and provide data for monitoring, evaluation, and learning.

2.8 Summary

In implementing the OWPVW, the accessibility of the application process, processing speed and uniformity of decisions are central to its success. The online nature of applications, whilst intended to speed up the process, can be complex to access for workers with limited computer access or access to translation services. The speed of decision making is classified urgent with a five-day application processing target for IRCC officers, which has required a significant investment in IRCC capacity to meet it. Whilst current OWPVW evidentiary requirements are considered resource intensive, this pressure could be eased through data sharing protocols, greater clarity on evidence required to meet standards of proof and by drawing on oral evidence. It is important that interviews are conducted by officials trained in trauma informed practice so that this process is positive for vulnerable workers. The length of open work permits should reflect evidence of the time it takes for workers to recover and find alternative safe and sustainable employment. In order to assist the design and development of open work permits, information on decisions and a review facility can help with monitoring, evaluation and learning systems.

2.9 Relevant considerations for any open work permit for vulnerable workers

Any open work permit for workers at risk of or experiencing abuse should:

- Be accessible for all, without requiring evidence of complaints to enforcement agencies or a report from an intermediary organisation which can present a barrier to access.

- Ensure all relevant materials are translated into the native languages of temporary migrant workers.

- Be accompanied by funding for proactive engagement by support organisations to address specific application support needs experienced by vulnerable workers.

- Be assessed and delivered urgently, the Government of Canada’s five-day target for OWPVW application processing is positive in this regard, sufficient funding should be provided for this.

- Consider a trauma informed oral evidence gathering process instead of written requirements for applications or evidence, interviews should be accessible and include facility for workers to be accompanied and provision for interpretation.

- Establish a two-step assessment process, applying an achievable standard of proof to evidence, recognising that the open permit is designed for highly vulnerable individuals and that labour abuses can be hard to evidence.

- Publish decisions made and include a formal review facility within the open work permit.

3. OWPVW outcomes for workers

The OWPVW’s objectives are to provide migrant workers on employer and sector-specific work permits experiencing or at risk of abuse with a means of leaving their employer without becoming undocumented and to increase engagement of such workers in labour inspections and enforcement action. The Government of Canada measures applications and approval rates, and compliance activity and outcomes to assess whether these objectives have been met. In addition, two Canada based NGOs have recently conducted reviews of the OWPVW for its impact on workers, which has provided useful evidence and recommendations for improvement. The following section will consider the impact and outcomes of the OWPVW on reducing the risk of worker abuse for workers on employer and sector-specific work permits in Canada.

3.1 Government assessment of outcomes

The Government of Canada has not conducted any review of the OWPVW for its impact on vulnerable workers and incidences of abuse, nor was this considered in the assessment of the BC Pilot. However, two metrics are cited as linked to programme assessment: recorded data on employer compliance activity and outcomes; and the uptake and numbers of successful applications (Government of BC). In terms of compliance activity, one analysis found approximately one third of inspection referrals result in inspections, yet OWPVW triggered inspection outcome data is not routinely tracked (ARHW 2021 pp.21-22). In the case of the BC Permit, delivered from 2016-18, there were 75 applications with a 90 per cent approval rate (Government of BC). Data for the federal OWPVW shows 1,080 applications in 2020 with a 55 per cent approval rate and 813 applications in January-July 2021 with a 63 per cent approval rate (Aziz 2022 p.41). Anecdotal evidence from support organisations suggests that workers are much more likely to be successful if they receive assistance with their application, and/or reconsideration, from expert organisations. Applications and approval rates are useful tools for assessing the need for any open work permit, however data is influenced by the level of support available for workers.

3.2 NGO reviews of outcomes

The impact of the OWPVW on workers has been documented by NGOs supporting workers in two reports on the scheme published in 2021 by the Migrant Workers Centre BC (MWC) and the Association for the Rights of Household and Farm Workers (ARHW). Through interviews with support organisations and review of applications, these reports evidence the impact of engagement with the OWPVW process on workers. Both reports identified important evidence of workers feeling re-victimized by re-living their trauma during the OWPVW application (ARHW 2021 p.16, Aziz 2022 p.22). The range of recommendations made in these reports have informed the recent OWPVW amendments and developments to implementation. Implementation evidence is therefore very important to programme development and external review of the OWPVW by support organisations provides useful learning to embed in any transfer of policy.

3.3 Outcomes for workers

Research participants raised the importance of the OWPVW providing a rapid route out of abusive employment for workers. Departure from work with tied accommodation can be challenging for workers without an income to pay for alternative housing, with some NGOs funding emergency accommodation. However, some interviewees highlighted how rapidly workers find new employment, including in new labour sectors:

Other employment is found really fast, the worker I accompanied chose to change industry and to exit agriculture, but lots of them find a job on other farms quickly. When they want to stay in agriculture, we are better placed to help them find another job, we can make a few phone calls and it’s really easy (Véronique Tessier, RATTMAQ).

Workers that are supported to find alternative employment are viewed by support organisations as less likely to fall into further risky working situations. Some interviewees highlighted a potential barrier the OWPVW could pose to recruitment, as the visa code is printed on the work permit making a worker identifiable as someone who has previously reported abuse (Daniel Lee, Fasken). However, support organisations have not found evidence of this posing a barrier to employment, this is attributed to limited understanding of what the visa codes represent and the buoyant labour market.

Whilst finding work is reported to be easy for individuals on the OWPVW, its 12-month validity can limit their recovery. Some workers are reportedly becoming undocumented, whilst others are re-entering tied temporary employment (Amanda Aziz, MWC, Véronique Tessier, RATTMAQ). Interviewees noted how little choice people had at the end of the 12 months and highlighted the risk of re-victimisation the tied-visa poses. Therefore, some interviewees recommended offering specific employment finding services alongside the OWPVW, to help workers find safe and sustainable alternative employment. Additionally, some interviewees had observed a need to enable workers to renew the OWPVW. Whilst outcomes are generally felt to be positive for workers during the validity of the OWPVW, the visa creates a cliff edge by setting a maximum of 12-months validity, at which point some workers are re-entering high-risk tied employment.

3.4 Impact of OWPVW on support organisations

As set out above, support organisations assisting OWPVW applicants are experiencing a significant drain on their resources. Many interviewees offering direct support to workers raised concerns about the huge diversion of their resources towards supporting workers to access the OWPVW from other frontline support work. NGOs with limited means are offering emergency accommodation and food to workers applying for the open work permit, as there is currently no State provision for such needs. One interviewee said their organisation now allocates a large percentage of resources to the OWPVW:

half of our budget is now going to support workers during the time they are waiting on the outcome of applications (Amy Cohen, RAMA).

For workers in tied accommodation, support for alternative housing whilst they pursue an OWPVW application is even more urgent, as without this they face the high risk of remaining in employer accommodation whilst their application is processed. The resource intensity of supporting workers applying for the OWPVW is leaving frontline organisations very stretched, significant thought is required at design stage to understand worker support needs and resource requirements for support.

3.5 Summary

To date there has been no formal evaluation of the wider impact of the OWPVW. However, due to the link between the OWPVW and workplace inspections, data on related compliance activity and outcomes is recorded and tracked by way of measuring wider impact. In addition, two frontline organisations have conducted their own reviews identifying areas for improvement to improve access to the OWPVW, worker engagement and outcomes. Workers accessing the OWPVW are largely found to be able to leave employers and enter alternative work, which offers short-term protection. However, the inability to extend the OWPVW and lack of transition permit means many workers re-enter tied temporary employment once the permit expires. The high uptake of the OWPVW is demonstrates the need for the work permit, yet frontline organisations note that applications and approval rates are influenced by the level of support available to workers. This support is limited without dedicated funding allocated to support organisations. The diversion of resources by support organisations to OWPVW applications and emergency assistance to applicants is having a knock-on impact on existing services and capacity.

3.6 Relevant considerations for any open work permit for vulnerable workers

Any open work permit for workers at risk of or experiencing abuse should:

- Include funding to support providers to assist applicants with housing and food once they have left their employer.

- Be extendable at the end of its validity period upon consideration of the workers’ circumstances

- Be associated with a migrant worker employment programme, to assist workers on open work permits to find safe and sustainable future work.

- Include monitoring, evaluation and learning to ensure that its impact on vulnerable workers and incidences of abuse can be understood and programme alterations made if required.

- Ensure data on outcomes of employer inspections linked to open work permits issued is documented and tracked to monitor wider impact of the permit.

Discussion and conclusions

The Scottish Government has recognised risks of abuse and exploitation for workers on the UK SWV and has commissioned research to identify options for safeguarding workers on temporary migration programmes. This Report has detailed the risks of exploitation on temporary migration programmes, acknowledging the growing number of workers on short-term visas in the UK since Brexit. It underlines the UK Government’s resistance to altering the two key drivers of risk on such visas, the tie with an employer or single labour provider and the temporary status of workers. It has documented similar resistance on the part of governments in comparative countries. Therefore, an interim policy option has been developed to safeguard workers in both New Zealand and Canada through an open visa for workers at risk of and in situations of abuse. Whilst such open work permits offer interim safeguarding options, there is a large body of evidence pointing to the need to end employer or single labour provider visa ties in temporary migration programmes and ensure such visas are convertible with pathways to settlement.

Whilst steps to rethink visa ties and short-term visas are essential first steps to safeguarding workers on temporary migration programmes, interim measures can offer temporary protection for workers. This Report considers the open work permit for workers at risk of and experiencing abuse as a possible safeguarding mechanism to reduce the risk of abuse and exploitation for workers on temporary migration programmes. It examines in detail the case study of Canada’s OWPVW, analysing lessons from an early Province of BC open work permit pilot which contributed to the design of the OWPVW, and from three and a half years of implementing the OWPVW nationally. The Report sets out the OWPVW’s objectives, to provide a safeguarding route to workers at risk of or in abusive situations and to facilitate workplace inspections, and key design features, from application, to consideration and decision making to wider impact. Interview data and secondary research is used to analyse each of these stages looking at issues such as their accessibility to vulnerable workers, the uniformity of application, transparency of decisions and utility of the OWPVW once issued. Considerations are provided for governments seeking to establish an open work permit for workers at risk of or experiencing of abuse.

Examination of the OWPVW case study shows open work permits for workers at risk of and in situations of abuse can serve to safeguard workers on temporary migration programmes, yet there are a range of important considerations to be made. The evidence from Canada shows that workers at risk of or experiencing abuse who transfer to an open work permit can leave abusive employers and find alternative work quickly, thereby creating an emergency pathway to an alternative and less risky visa. This pathway should therefore be available to all workers, regardless of status, and should be made as accessible as possible. Importantly, the definition of abuse should be broad enough to capture the range of possible circumstances faced by workers, with strong guidance and training for implementing officers. Decisions should be transparent and continuously monitored to ensure uniformity and to permit review, which should be integrated into any open work permit for workers at risk of or experiencing abuse.

The need for workers at risk of or experiencing abuse to leave their workplace immediately should be considered, and an urgent application processing target set. Significant resources may be required for such a target is to be met and a pilot open work permit programme can offer evidence of potential demand to ensure resourcing requirements are identified early. Additional resources should be provided to support organisations to facilitate support and emergency assistance, including legal advice, housing, food, and employment advice. This emergency approach recognises that once a worker raises a case of abuse, they put themselves in danger, particularly where they live in tied employer accommodation.

In order that an open work permit can have a wider impact beyond individual cases and serve as a deterrent to unscrupulous employers, it is important that when a permit is issued information detailing worker allegations is shared with labour market enforcement authorities. Targeted inspections should be immediately triggered by such information sharing, including unannounced workplace visits. Considering the vulnerability of workers on temporary migration programmes, evidence of pro-active steps taken by employers to identify and address abuses should be a minimum requirement of any associated inspection function. Data from such inspections if collated and monitored contributes to evaluation and learning about the wider impact of an open work permit.

The length of an open work permit is important and should be based on evidence of how long it could take workers to find alternative employment and recover from abuse. Given how variable each worker’s experience will be any open work permit should be extendable based on an assessment of circumstances. An overall objective for an open work permit should be to ensure workers accessing an open work permit find safe and sustainable employment enabling them time for recovery and restitution and to prevent repetition of abuses. Monitoring data should seek to assess the contribution of open work permits to helping workers to access stable employment pathways free from abuse and to reducing further incidences of abuse for temporary migrant workers.

This case study review provides lessons for the Scottish Government should it consider proposing the interim measure of an open work permit for temporary migrant workers at risk of or experiencing abuse. Through detailed analysis of the design, implementation and outcomes of the OWPVW the Report has assessed the potential for transferring the model to Scotland and the policy considerations needed. This Report concludes that whilst the priority remains reforming the UK’s temporary migration schemes, open work permits can help safeguard workers and could be considered as an interim measure for Scotland.

Contact

Email: Migration@gov.scot

There is a problem

Thanks for your feedback