Natural capital - importance to the Scottish economy: research

This research identifies sectors reliant on natural capital in Scotland and quantifies the economic value of these nature-dependent sectors at national and regional levels. The methodology values our economy's dependence on nature, estimating £40 billion economic output and 261,000 jobs supported.

Executive Summary

The aim of this study was to determine the industrial sectors in Scotland that rely on high-quality natural capital in Scotland and to quantify the economic value of these nature-dependent sectors at a national and regional geographic level. To achieve this, WSP and Economics for the Environment Consultancy (eftec) developed and applied a methodology for measuring the reliance of the Scottish economy on natural capital.

Measurement of the reliance on natural capital is fundamentally linked to Scotland’s National Strategy for Economic Transformation (NSET), principally in relation to goals around restoring natural capital.

Using the preferred methodology, and recognising this will still undervalue the total contribution of natural capital, the analysis identified that in 2019:

- Industries reliant on natural capital, excluding non-renewable resource sectors such as oil and gas, supported £40.1 billion of total economic output – 14.4% of Scotland’s total output, and around 261,600 jobs, directly and indirectly;

- The industries most dependent on natural capital included: agriculture, fishing and aquaculture (88% reliant), forestry and wood products (59%), water and sewage (40%), spirits / wine and beer / malt sectors (30%), and electricity (30%);

- The Highlands & Islands Regional Economic Partnership (REP), and Glasgow City REP were estimated to have the largest shares of output and employment reliant on natural capital; and

- The Highlands & Islands, Tay Cities, and South of Scotland REPs had a high share of key habitats in Scotland. For these three REPs, these key habitats provided ecosystem services (identified using the preferred method) estimated to be worth £2.1 billion in output in 2019 for all economic sectors in the Scottish economy.

What is reliance on natural capital?

Natural capital is defined in Scotland’s NSET as “the renewable and non-renewable stocks of natural assets, including geology, soil, air, water and plants and animals that combine to yield a flow of benefits to people”.[1] Natural capital reliance is where an economic activity is dependent on an ecosystem service in its value chain, including receiving material inputs, moderation of wastes and operating conditions, and customer motivations.[2]

It should be noted that in this study the main analysis focused on a renewables-based definition of natural capital. This means that sectors such as oil and gas were excluded as they are non-renewable resources (i.e. resources that will not regenerate after exploitation within any useful time period). As part of sensitivity analysis, the non-renewable industries were considered.

Scotland’s economy relies on natural capital through:

(i) the direct extraction of resources from forests, arable landscapes, oceans and other habitats that exist in Scotland;

(ii) the provision of ecosystem services such as healthy soils, clean water, pollination, temperature regulation, a stable climate, recreational activities and tourism; and

(iii) support to workforce and population health.

Existing economic reporting frameworks do not easily capture the value of natural capital, due to four key challenges:

- Traditional economic indicators may provide a limited view of natural capital reliance;

- Many of the natural capital benefits of ecosystem services do not have a market value, therefore the value of natural capital may not accurately reflect the relative importance of natural capital to an industry;

- The purchase patterns in the economy that are available may not be of sufficient quality to be used to estimate the reliance of Scottish industry on natural capital products; and

- Scottish System of National Accounts data are a static representation of the economy in a given year, and therefore cannot show how the economy ‘re-adjusts’ to changes in natural capital.

A three-step methodology to valuing natural capital reliance

As a result of these challenges, this study adopted multiple methods to explore how natural capital reliance could be measured within and beyond the boundaries of the System of National Accounts and Supply and Use Tables. The methods were distinguished by their breadth of measurement and degree of alignment to existing statistics.

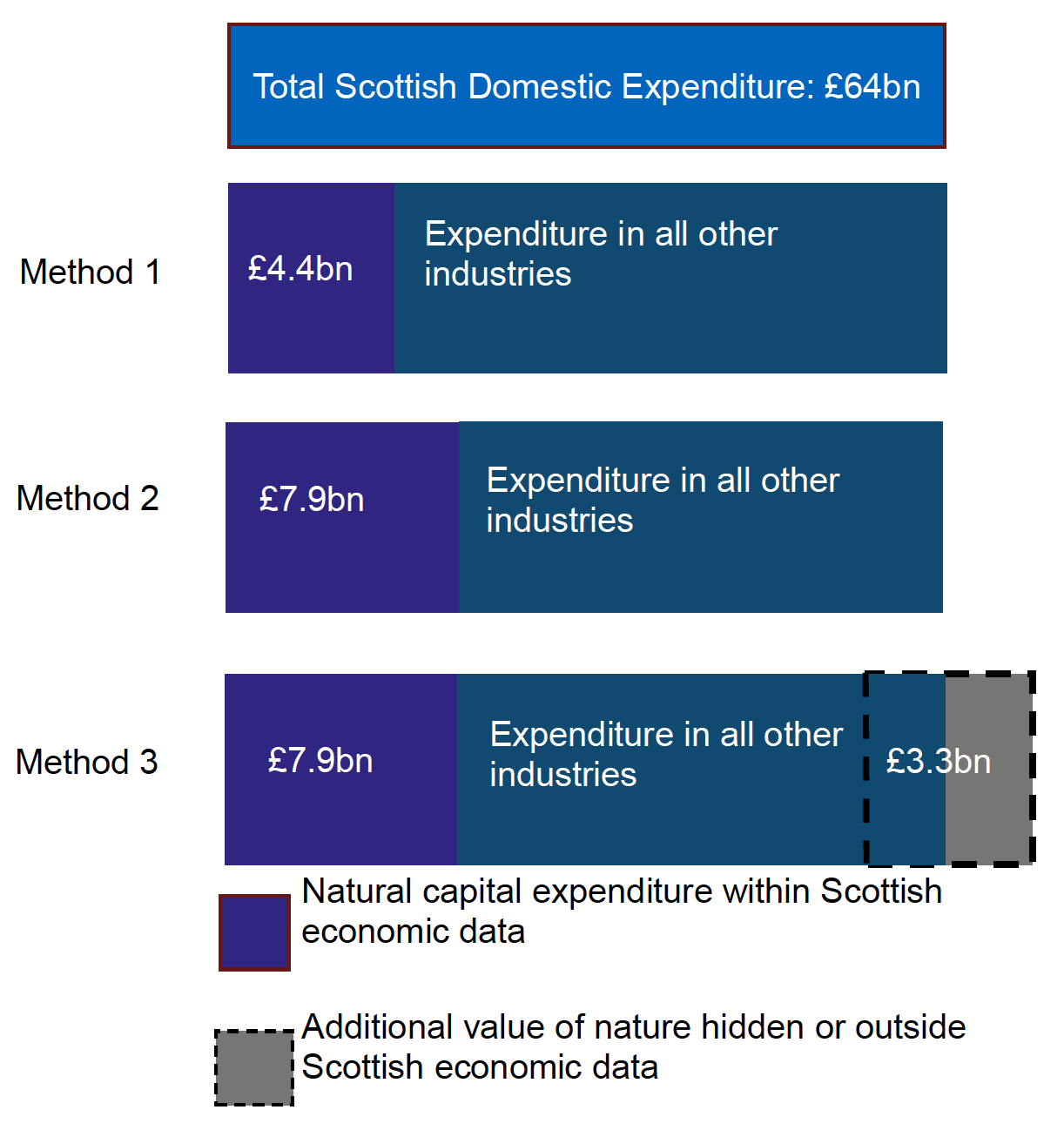

Method 1 provided a definition of natural capital reliance that drew on the existing System of National Accounts (SNA) data used to measure Scotland’s economic activity. While alignment to the SNA data enables replicability and updating of results, and a relatively straightforward calculation of economic impacts, its use in this study provided the narrowest measure of reliance on natural capital. Method 1 calculated the scale of economic activity in ‘core natural capital industries’. These included domestic expenditure[3] by the following sectors: agriculture, forestry planting, timber removals, fishing, aquaculture, renewable energy, and water and sewage supply. These industries were identified as those that directly extract renewable resources from the environment and have a market value. However, how other downstream industries rely on these core sectors was not captured, nor was the economy’s reliance on regulatory and cultural ecosystem services.

Method 2 built on the Method 1 approach by additionally estimating the domestic expenditure of all other sectors in the economy on the core natural capital industries mentioned above. For example, economic activity of Scottish whisky was not captured in Method 1. However, by including the spirits and wine industries’ spend on water and sewage, and agricultural products, a more comprehensive estimate of NC reliance was achieved. Additional calculations to measure economic impacts still drew on the Scottish national economic data.[4]

Method 3 built on the Method 2 approach by developing an index that attempted to capture industry reliance on a broad range of ecosystem services, and applying this index to expenditure values from Method 2. The index used the Exploring Natural Capital Opportunities, Risks and Exposure (ENCORE) database[5], which assessed the dependence of industry processes on natural capital. The uplift in expenditure from this index was used to estimate the non-market value of industry dependence on regulating and cultural ecosystem services. This additional expenditure moved beyond the Scottish economic data (SNA) underpinning the definition of natural capital reliance under Methods 1 and 2.

As depicted in the figure above, Method 3 expanded the measured size of Scotland’s domestic expenditure in industries that provided natural capital goods and services – from £7.9 billion under Method 2, to £11.2 billion under Method 3. This additional £3.3 billion represented the additional value of ecosystem services (e.g., surface water, flood and storm protection, water flow maintenance, ground water and erosion control) not captured within existing Scottish economic data (SNA). This domestic expenditure on natural capital can be considered as either: hidden within Scotland’s economic data boundary (SNA); or lying outside the envelope of the economy altogether, as shown in the figure above.

The following text provides a summary of the three main methods used to estimate reliance on natural capital, and the advantages and disadvantages associated with each.

Summary of Advantages and Disadvantages to Methods 1-3

Method 1

Advantages: Directly comparable to measures of national statistics, including employment and total output.

Disadvantages: Did not consider broader reliance of natural capital from ecosystem services that do not have a market value.

Only reflected the higher-reliant subset of sectors, omitted lower-reliance and downstream activities.

Method 2

Advantages: Used data from System of National Accounts to determine the sectors that spent the most on natural capital (‘provisioning’) goods and services. This expanded the definition of reliance to downstream sectors in the economy.

Disadvantages: Did not consider broader reliance of natural capital from ecosystem services that do not have a market value.

Caveat: To estimate the indirect and direct output, this method assumed the reliance on Scotland’s natural capital for salaries, wages, imports and net taxes in a given industry was proportional to the natural capital share of domestic expenditure.

Method 3

Advantages: Used data from System of National Accounts to determine the sectors that spent the most on natural capital (‘provisioning’) goods and services. This expanded the definition of reliance to include downstream sectors.

This method attempted to incorporate the reliance on non-provisioning services.

Disadvantages: Incorporating reliance of non-provisioning services was quantified in monetary terms using market values for natural capital expenditure as a basis. Order of magnitude estimates of regulating and cultural services dependent on extent to which a sector used provisioning services. Qualitative data was based on global dependence measures. Further expert judgement is required to adjust materiality to be specific to Scotland.

Economic impacts from the proposed methods to measuring natural capital reliance

Having estimated the amount of domestic expenditure in industries that rely on natural capital under Methods 1-3, the study used these estimates to derive values for the output generated by industries that were reliant on natural capital. The ratio of domestic expenditure to output was used for each industry to estimate the output reliant on natural capital. For example, domestic expenditure of £11.2 billion for natural capital goods and services would generate an output of £25 billion under Method 2. Natural capital output as a percentage of total output in the Scottish economy was also calculated. Importantly, the analysis enabled an approximation of total economic impacts (on output and employment).

The table below shows how the figures were derived for output of industries reliant on natural capital. Multipliers were used to understand how a change in output or expenditure by one company/industry creates further knock-on effects in the economy attributed to supply chain activities and spending from the additional income. The table below also shows that the level of output and employment effects were largest under the more expansive Method 3 compared to Methods 1 and 2.

Output of Industries Reliant on Natural capital (£bn) |

Total Scotland Output (£bn) |

Natural Capital Output as a % of Scottish output |

Output Effect (direct and indirect) (£bn) |

Employment Effect (direct and indirect) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Method 1 |

12.5 |

268 |

5% |

18.8 |

95,800 |

Uplift between Method 1 and 2 |

+12.5 |

+17.7 |

+135,600 |

||

Method 2 |

25.0 |

268 |

9% |

36.5 |

231,400 |

Uplift between Method 2 and 3 |

+£9.6 2.6 (Substitutable) 7 |

+3.6* |

+30,200* |

||

Method 3 |

34.6 |

278 |

12% |

40.1 |

261,600 |

Notes: “substitutability” refers to when it was considered possible to substitute the ecosystem services with physical capital, while “non-substitutability” refers to when production processes could not take place without the ecosystem service.

*Output and employment effect of substitutable share of nature related output only.

Based on the Method 2 definition of reliance on natural capital, approximately £25 billion (5%) of Scotland’s total £268 billion output in 2019 was reliant on natural capital. This nature-related direct output supported a total output effect of £36.5 billion for the Scottish economy by factoring in the indirect effect on the industries’ suppliers. This change in output supported directly and indirectly around 231,400 jobs in the Scottish economy.

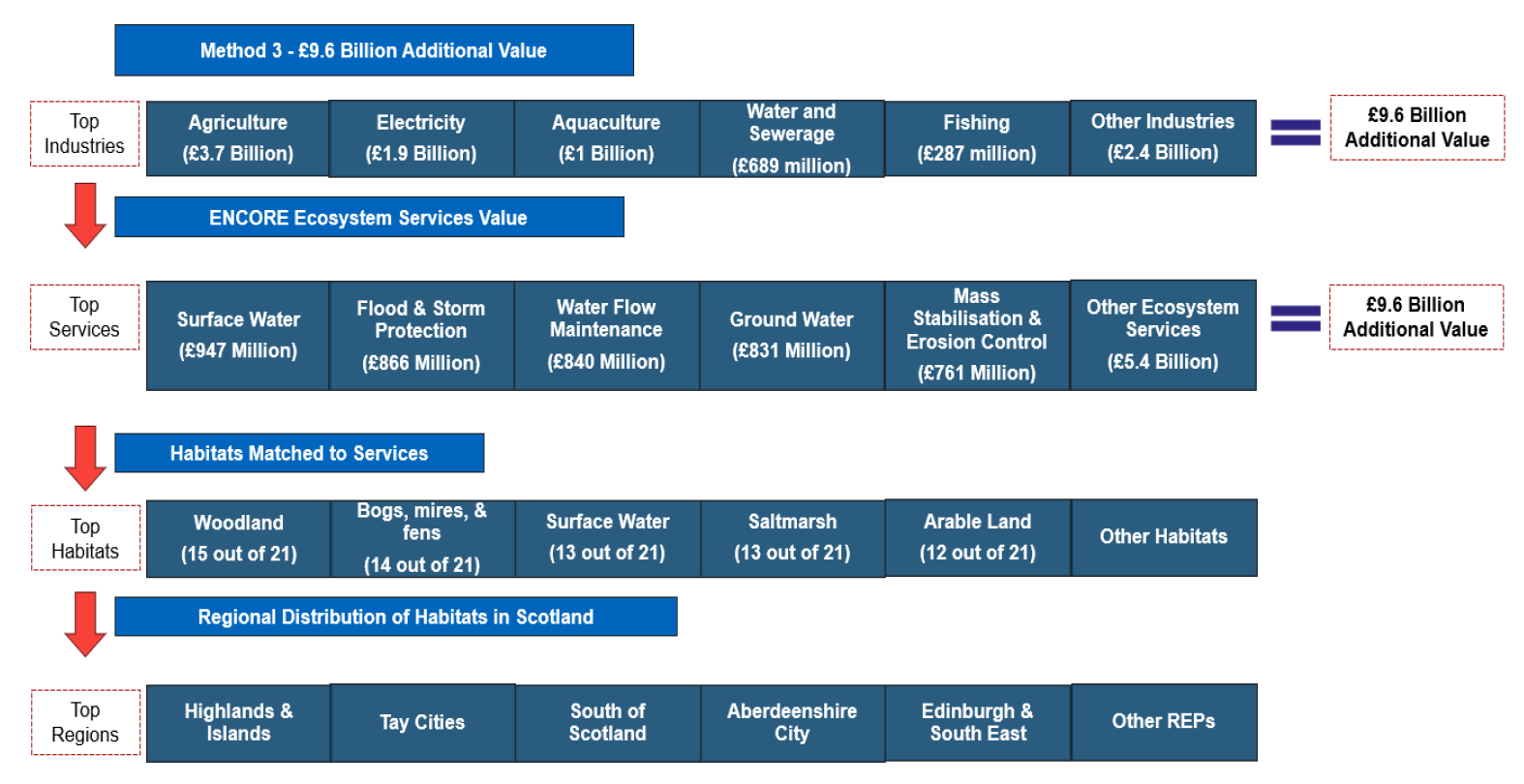

Using the Method 3 definition, around £9.6 billion of output, generated from the £3.3 billion domestic expenditure, can be defined as nature reliant across all the industries (using the renewable resources definition of natural capital reliance). As mentioned above, this additional amount was either hidden in the economic data (SNA) boundary or was outside it. Existing economic/statistical approaches, such as the SNA, are limited and do not reflect or capture the true or total value of natural capital. Recognising this additional value of nature, as defined in Method 3, took the total amount of nature-reliant output to £34.6 billion (£25 + £9.6 billion) for Scotland. However, it was not possible to measure the total output and job effect (direct and indirect effect) of this number, as the £9.6 billion lay outside of the Scottish economic accounts. This £34.6 billion was the potential value of nature provided by provisioning and non-provisioning services by various habitats in Scotland.

However, under Method 3, certain ecosystem services can be substituted by engineering solutions and human capital. It is important to note that this study does not imply a transition away from natural capital and towards engineering solutions and human capital as substitutes. Method 3 used these alternative solutions as a proxy: industries that had substitutable ecosystem services were mapped to human capital and/or nature-based solutions that could be used to provide these ecosystem services if the natural capital was lost and/or degraded.

Based on this approach, £2.6 billion (or 27% of the additional £9.6 billion) was identified as being ‘substitutable’. This £2.6 billion would create an output effect (direct and indirect) of £3.6 billion, as well as an employment effect of an additional 30,200 jobs. This took the total estimated direct and indirect output effect to £40.1 billion (£36.5 billion estimated from Method 2 + £3.6 billion from Method 3), and total direct and indirect employment effect to 261,600 jobs (231,400 estimated from Methods 1 and 2 + 30,200 jobs from Method 3).

Regional impacts of industries reliant on natural capital shows Highlands & Islands and Glasgow City as the main beneficiaries

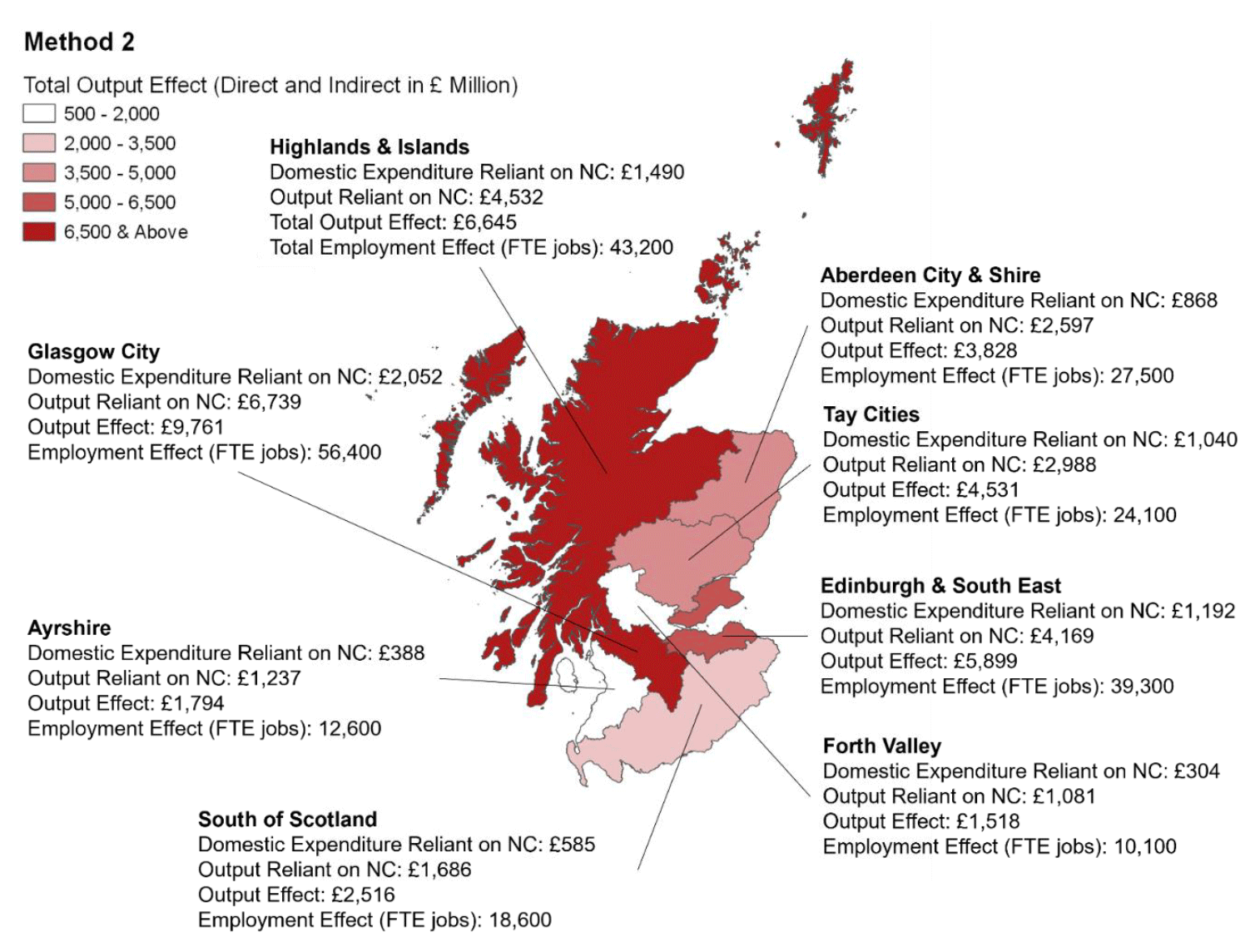

Under Methods 2 and 3, the Highlands & Islands and Glasgow City Regional Economic Partnerships (REP) had the largest shares of estimated output effect and employment effect, due to these areas’ economic reliance on the agriculture and electricity industries. It is worth noting that Glasgow City REP is reliant on natural capital located in rural areas across Scotland. This being said, the data on output and employment in the electricity sector represented economic activity in Glasgow REP itself.

Economic Reliance on Natural Capital – Method 2 Results

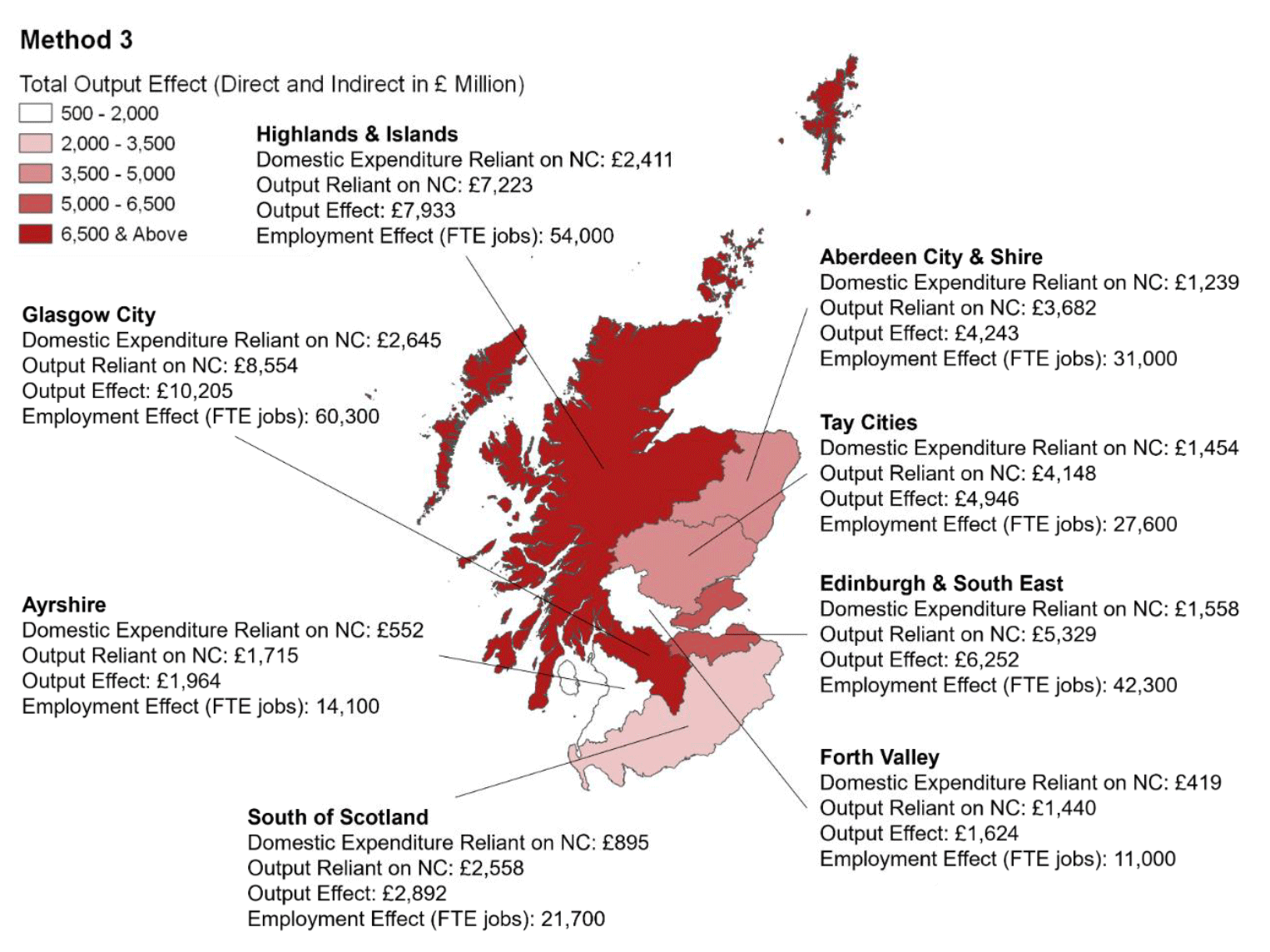

Under the Method 3 uplift, the largest increase in output and employment effect was in the Highlands & Islands REP. This is due to the area’s economy being more reliant on the agriculture, forestry planting, forestry harvesting, fishing, and aquaculture industries. These industries were all found under Method 3 to be highly reliant on ecosystem services.

Economic Reliance on Natural Capital – Method 3 Results

Ecosystem services are provided by key habitats in Scotland concentrated in the Highlands & Islands that support jobs and economic growth

As identified using Method 3, and as shown in the figure below, economic industries in Scotland are reliant on different ecosystem services, beyond that of provisioning services captured in the System of National Accounts. The ecosystem services that support and enable industries to function are provided by habitats across Scotland. Habitats in Scotland were mapped using Scottish Government’s published habitat GIS mapping tool. Ecosystem services from ENCORE were mapped to the habitats which provide them. The habitats were depicted across the eight REPs in Scotland. The share of output reliant on nature for key ecosystem services (e.g., surface water, flood and storm protection and water flow maintenance) across the eight REPs for the top 5 industries as per Method 3 and ENCORE had a large presence in the Highlands & Islands, Tay Cities and South of Scotland.

Although there are many reasons beyond natural capital reliance for a business to locate in a certain area, it suggests that the proximity to the habitat for which the industry relies on for its ecosystem services may play a hidden but important role. For example, food and beverage industries, whisky distilleries, and the fisheries industry would choose to locate close to the habitats providing important provisioning and non-provisioning services for these industries.

Contextualisation of results with previous studies

This study built on previous studies that have sought to understand the economic importance of investing in natural capital in Scotland: Understanding the local economic impacts of natural capital investment (2022), and Assessing the cumulative and cross-sector economic benefits of investment in natural capital in Scotland (2023).

The contribution of natural capital to the economy has been explored globally, and in Scotland and European jurisdictions (see ‘Summary of findings from related studies’). In 2008, the contribution of natural capital to the economy was estimated at 11% of total output (Cambridge Econometrics, 2008) and 242,000 jobs, based on a subset of natural capital industries.[6] A more recent study estimated the reliance of the economy on natural capital at 55% of Gross Domestic Product (PwC, 2023).[7] [8] Estimates from the PwC study included the proportion of the economy that was ‘moderately’ and ‘highly’ reliant on natural capital based on the materiality assessment used in ENCORE. Method 1 represented the most conservative estimate of natural capital, where £18.8 billion of total output relied on natural capital. This represented 7.0% of Scotland’s total output in 2019, and 95,800 jobs. Method 3’s use of qualitative data to uplift expenditure (a different use of the materiality assessment compared to the PwC study), increased this figure to £40 billion in 2019 (or 14.4% of total output) and 261,600 jobs.

This study also complements existing work from Scottish Government on Recognising the Importance of Scotland’s Natural Capital (2023), which highlighted key insights from the Natural Capital Asset Index (NCAI) and the Natural Capital Accounts (NCA). The NCAI tracks in non-monetary terms how well Scotland’s habitats can provide ecosystem services that contribute to people’s wellbeing. The NCA estimate – in line with international guidelines – monetary values for a number of the ecosystem services that our environment brings to society.

Summary of findings from related studies

Source title, author and year of publication:

Nature Risk Rising, World Economic Forum (2020)

Key findings:

US$44 trillion of global GDP (more than half) was moderately or highly dependent on nature and its services.

Source title, author and year of publication:

Managing nature risks: From understanding to action, PwC (2023)

Key findings:

US$58 trillion of global GDP (approximately 55%) was moderately or highly reliant on natural capital.

Source title, author and year of publication:

The Economic Impact of Scotland’s Natural Environment, Cambridge Econometrics (2008)

Key findings:

The estimated value of the natural environment to the Scottish economy was as high as £17.2 billion in 2003 (based on type II effect – aggregation of direct, indirect and induced effects), which represented 11% of total output and 242,000 jobs (direct, indirect and induced).

Source title, author and year of publication:

Biodiversity impact and ecosystem service dependencies, Government of the Netherlands (2021)

Key findings:

Assessment of direct dependencies provided valuable information on potential impacts. The combined result of an impact and dependency profile could show the extent to which a company can influence ecosystem services it depends on.

Source title, author and year of publication:

The ecosystem contribution to tourism and outdoor leisure, eftec (2019)

Key findings:

Habitats with the largest contribution to T&OL activities were "coastal margin" and "marine"; T&OL expenditures for Scotland broken down by activity expenditure (£4,014 million), ecosystem attribution (£2,534 million) and ecosystem GVA (£1,169 million) annually.

Source title, author and year of publication:

Scotland’s Natural Capital Accounts, Scottish Government (2023)

Key findings:

The total annual value of ecosystem services excluding oil and gas was £3 billion in 2019 (in 2021 prices). The total annual value increased to £15 billion when provisioning services from oil and gas were included. This estimate included both market and non-market value approaches to estimate provisioning, regulating and cultural ecosystem services.

Source title, author and year of publication:

Assessing the Materiality of Nature-Related Financial Risks for the UK, Green Finance Institute (2024)

Key findings:

Scenario analysis by Green Finance Institute estimated that nature degradation could lead to 12% GDP loss to the UK compared to the business-as-usual baseline.

Summary of main findings and recommendations

Natural capital is important to the Scottish economy, as it supports many industries, jobs, and regions.

- This study estimated a £40.1 billion reliance of the Scottish economy on natural capital, with around 261,600 jobs estimated to be supported by natural capital. In other words, at least 14.4% of Scotland’s total economic output was estimated to be reliant on natural capital.

- The sectors found to be most reliant on natural capital were agriculture, fishing and aquaculture, forestry, water and sewage, spirits and drinks, and the electricity sectors (Method 3 results).

- The regions found to be most reliant on natural capital were in the Highlands & Islands, and Glasgow Regional Economic Partnerships (Method 3 results).

- The Highlands & Islands, Tay Cities, and South of Scotland REPs had a high share of key habitats providing ecosystem services, worth £2.1 billion in output in 2019 for all sectors in the Scottish economy (Method 3 results).

- It is worth nothing that, while these were the most robust estimates available using the approach adopted in this study, the range of estimates should be treated as a lower limit for Scotland’s reliance on natural capital. These values are conservative as formal recognition of the non-provisioning value of nature, especially the non-substitutable share, would further increase the share of total output reliant on nature.

Definition of natural capital as based on renewable resources.

- This study adopted a renewables-based definition of natural capital. The estimates of the analysis excluded sectors reliant on non-renewable resources (i.e. resources that will not regenerate after exploitation within any useful time period). The non-renewable industries were considered as part of a sensitivity analysis.

- Industries supported by non-renewable sectors included mining and mining support, coal and lignite, oil and gas extraction, and metal ores. A proportion of output from electricity generated from non-renewable resources (47% of total energy consumption in 2019) was included as well.

- Including non-renewable industries in the definition of natural capital increased the contribution of natural capital to the Scottish economy in Method 1 estimates significantly. This increase was largely driven by the inclusion of the remaining non-renewable electricity generation.

Method 3 findings showed that provisioning ecosystem services are highly valuable for certain industries but not captured in conventional statistical systems measuring economic activity.

- The market value of natural capital may not accurately reflect the relative importance of natural capital to an industry. Metrics such as gross domestic product and gross value added do not capture the value of natural capital except where it provides revenue on the market.

- Only 27% of provisioning ecosystem services could be substituted by engineering solutions or human interventions. This shows the limited ability of our economic system to replace essential ecosystem services.

- Additional surveys and monitoring systems would be required to reflect the value of ecosystem services in our economic system.

Regional analysis also showed the weakness of conventional statistical systems in demonstrating the economic importance of natural capital industries.

- Some regions may have higher output or job values for industries highly reliant on nature if the head office is located there rather than the location of the nature-based economic activity.

- The Highlands & Islands, Tay Cities and South of Scotland had a high share of key habitats providing eco-system services worth £369 million domestic expenditure and £1.1 billion in output in 2019 for the top 5 industries.

Given the different approaches to measuring the economic value of industries’ reliance on nature, several methods were presented in this study to provide a range of estimates.

- While an objective of the study was to improve on the measurement of the economic value of industries’ reliance on nature in economic statistics, a starting point was to measure that reliance within current statistics, which identified £12.5 billion of Scottish output reliant on natural capital, representing 5% of Scottish total output (in 2019).

- When downstream sectors in the economy were considered, this increased to £25 billion (9% of Scottish output).

- If non-market but vital ecosystem services were also considered, then economic reliance on nature came up to £34.6 billion (around 12% of Scottish output), and when substitution and multiplier effects were factored in, this increased to £40 billion (14% of Scottish output).

- A range of job estimates were associated with these different scopes of methods: an estimate of 261,600 jobs reliant on nature (based on the £25bn figure) aligned to similar estimations in a Cambridge Econometrics study from 2008 of 242,000 jobs.

The link between habitats, ecosystem services and economic impacts shown in this study emphasises the importance of maintaining natural capital.

- Traditional statistical accounting systems do not reflect the value placed on maintaining natural capital, but reflect social and political preferences of valuing resources and their uses.

- Industries that are highly reliant on natural capital should directly support their supply chain to better manage the key habitats that provide nature-based services and inputs. Companies can also protect or enhance habitats as part of their Environmental, Social & Governance (ESG) and Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) compliance as recognition of the vital ecosystem services for their production activities.

- Policy makers should recognise this non-market and social value of nature and communicate the benefits along with traditional economic data. Habitats that provide ecosystem services that are not substitutable should be protected or given more importance in environmental management and developmental policies.

- Degraded or lost habitats can have important repercussions for the economy, including:

- Higher cost of replacing nature-based inputs or services

- Potential for direct jobs in nature protection or management being replaced by jobs in the manufacture of synthetic substitutes, leading to regional labour market imbalances

- Higher cost of damage and repair, and possible higher insurance costs

- General decline in productivity of the economy.

Contact

Email: matylda.graczyk@gov.scot

There is a problem

Thanks for your feedback