Natural capital - importance to the Scottish economy: research

This research identifies sectors reliant on natural capital in Scotland and quantifies the economic value of these nature-dependent sectors at national and regional levels. The methodology values our economy's dependence on nature, estimating £40 billion economic output and 261,000 jobs supported.

Desktop Review

Desktop Review Approach

The desktop review identified and reviewed sources that were relevant to the development of the natural capital framework. The purpose of the review was twofold:

1. To carry out a critical assessment of previous approaches to estimating the reliance on natural capital, including the definition and measurement of the ‘reliance’ of an economy or industry on natural capital; and

2. To collect publicly available data and identify data gaps. The data incorporated into the analysis included the Scottish Input-Output (I-O) Tables, the Scottish Natural Capital Accounts, and the Tourism Satellite Accounts (available at the UK level).

Identified evidence was sourced from academic literature, grey literature, and government datasets. A subset of sources was provided by Scottish Government, and the remaining sources were identified by the Project Team. Relevant sources were identified by the Project Team according to the source citation (i.e., author, year of publication, broad source type); industrial sectors and natural capital reliance (e.g., sectors and sector value, SIC codes, location); and natural capital (e.g., assets, habitat types, ecosystem services and benefits).

In total, the desktop review log contained 15 unique sources. This included Scottish valuation datasets that have been referenced throughout this project, namely the Scottish Natural Capital Accounts (2023) and the Scottish Supply, Use and Input-Output Tables (2023). Table 1 highlights key information from a selection of the sources reviewed which had methodological relevance to this study. It summarises the key findings, discussion of relevant topics (i.e., primary industries, supply chain, ecosystem services, scoring assessment, and non-renewable services), and any additional notes.

Nature Capital Reliance

Natural capital ‘reliance’ (also referred to in the literature as natural capital ‘dependence’) can be understood, as the dependence on natural capital assets and ecosystem services for carrying out economic activities. The Scottish economy relies on natural capital through market-based activities, for example, the supply of raw materials such as timber, fish, or agricultural produce that can be bought or sold. These are referred to as provisioning ecosystem services and include any ecosystem good or service extracted from nature.

Scottish industries may also rely on natural capital through the ecosystem services that are not reflected in market statistics. For example, the agricultural sector relies on regulating services, such as pollination, which provides an estimated £43 million per year in economic value to agricultural and horticultural crops, and honey production in Scotland (valued in 2011 pounds).[9] Moreover, in terms of cultural services, the natural environment makes significant contributions to local and regional economies in Scotland. For instance, the direct economic impact of nature-based tourism in Scotland is £1.4 billion per year, which is associated with 39,000 direct full-time equivalent jobs and visitor spending of more than £4 billion per year (in 2010 pounds). [10] Activities that contribute to Scotland’s nature-based tourism market include wildlife watching (estimated at £117 million in value per year in 2010 pounds) and walking and mountaineering (estimated at £533 million in value per year in 2010 pounds), among others. Both values are estimated in Bryden et al. (2010).

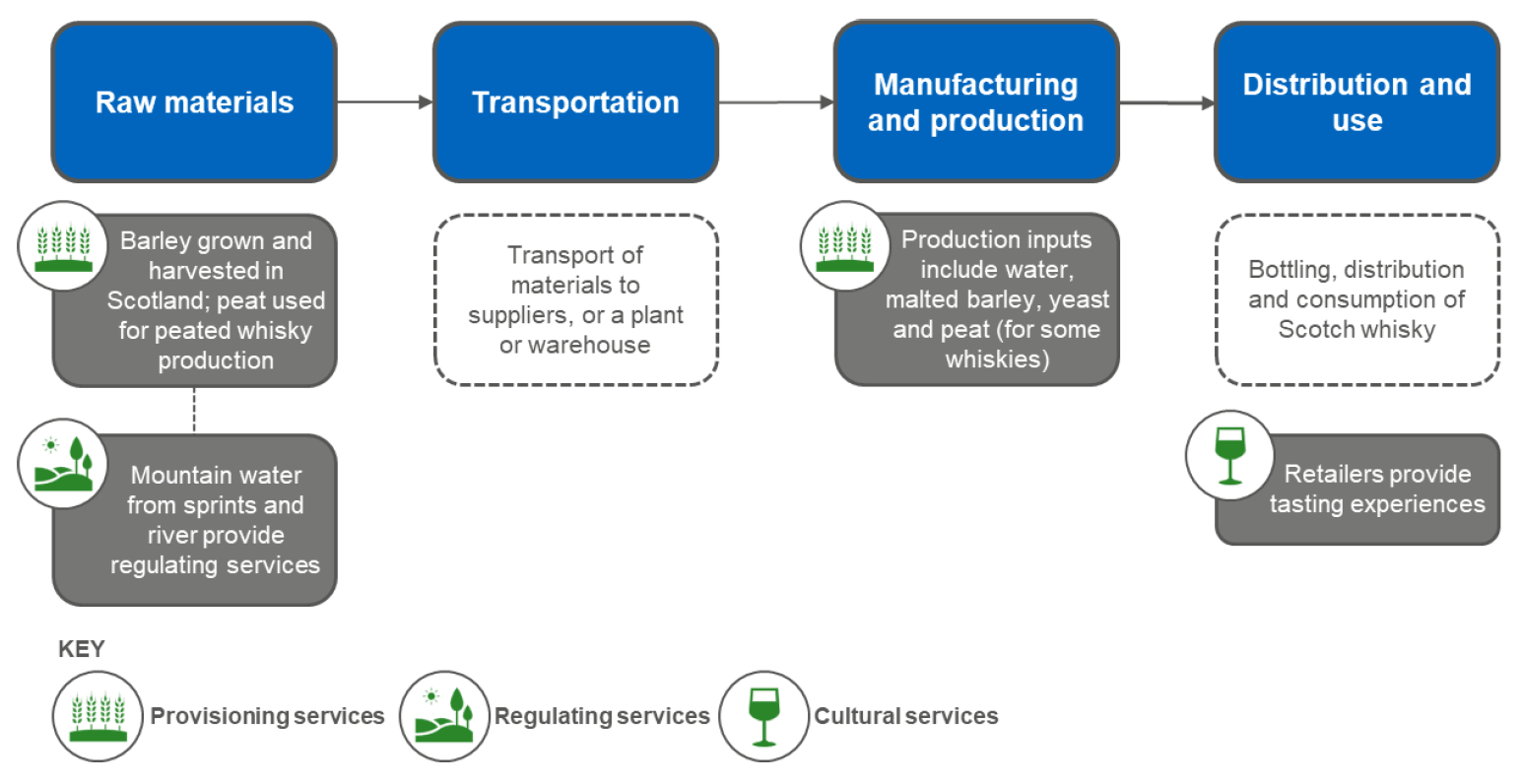

Many sectors in the economy rely on a combination of services from natural capital. Figure 2 aims to illustrate (using the Scotch whisky sector as an example) how a sector relies on natural capital, by reflecting several inputs which are otherwise not fully captured in market economic data.

Source: Adapted from The James Hutton Institute and MOVING (EU Horizon 2020)[11]

Natural capital, in the form of material inputs to support other sectors in the economy, can be reflected in economic reporting using metrics such as employment and gross value added (GVA). However, there are two key challenges to defining natural capital reliance according to an economic market value:

- Non-market values of natural capital ecosystem services are not captured, therefore providing a limited view of the true natural capital reliance of the Scottish economy.

- The market value of natural capital products – or raw materials – is typically lower than other products that require additional manufacturing processes. The market value of natural capital may not reflect the relative importance of natural capital to an industry that purchases those materials.

The 2008 Cambridge Econometrics study commissioned by NatureScot (formerly Scottish Natural Heritage) defined natural capital reliance by applying a percentage link to the natural environment, where ‘natural environment’ is defined as ‘the natural materials, processes, habitats and species, and topography that exist in Scotland’. The link was estimated according to the proportion of each industry with ‘the need for a high-quality environment, rather than exploitation of the environment’.

In a more recent assessment, the Office for National Statistics (ONS) article entitled Developing supply and use tables for UK Natural Capital Accounts: 2023 adopted a narrow definition of natural capital reliance limited to natural capital goods and services supplied by economic units. Consequently, the analysis was limited to market values of provisioning services.

A 2020 World Economic Forum (WEF) report Nature Risk Rising adopted a wider definition, where economic reliance (or dependence) was defined in two ways: (i) the direct extraction of resources from forests and oceans, or (ii) the provision of ecosystem services such as healthy soils, clean water, pollination and a stable climate.

For the purposes of this analysis ‘natural capital reliance’ is defined as in Box 1 below.

Box 1: Definition of ‘natural capital reliance’

'Natural Capital' is defined in The Environment Strategy for Scotland: vision and outcomes (2020) as "the environmental resources (e.g, plants, animals, air, water, soils) that combine to yield a flow of benefits to people".

Natural capital reliance is where an economic activity is dependent on an ecosystem service in its value chain, including receiving material inputs, moderation of wastes and operating conditions, and customer motivations.

Scotland's economy relies on natural capital by:

(i) the direct extraction of resources from forests, arable landscapes, oceans and other habitats that exist in Scotland;

(ii) the provision of ecosystem services such as healthy soils, clean water, polination, temperature regulation, a stable climate, recreational activities and tourism; and

(iii) support to workforce and population health.

The Scottish economy is defined by industrial sectors classified according to the UK Standard Industrial Classification (SIC) of Economic Activities, 2007 version (which is the most recent revision).[12] The Scottish Supply-Use Tables adopt this industrial classification typology for statistical reporting.

Similarly to how the literature and evidence base points to different potential ways of defining natural capital reliance, the degree to which the economy and its constituent industrial sectors rely (depend) on natural capital can also be measured in various ways.

Estimation Approaches

This section presents a review of the different approaches for estimating natural capital reliance in Scotland. These are explored in more detail in this section and summarised in Table 1.

At the Scottish geographical level, the Scottish Supply, Use and Input-Output Tables (2023) form the core secondary datasets for this analysis on the Scottish economy’s reliance on natural capital. The Supply, Use and Input-Output Tables are organised according to UK SIC 2007 codes. The System of National Accounts (SNA) method uses Gross Value Added, employment measures and other productivity-related values (e.g. non-SNA health benefits) which can be used in valuation methods.

Scottish Supply, Use and Input-Output Tables are fundamentally different from the Scottish Natural Capital Accounts (2023), produced by ONS on behalf of the Scottish Government which measure the value of the assets and the annual flow of services that natural assets provide. The NCA dataset incorporates non-market valuation techniques, such as avoided quality adjusted life-years to measure benefits from natural capital such as noise mitigation, air pollution removal and urban cooling.

The Natural Capital Asset Index, produced by NatureScot tracks how well Scotland's habitats can provide ecosystem services that contribute to quality of life. It comprises 38 quality indicators of Scottish habitat characteristics, and is used to measure the environment’s capacity to provide benefits, rather than determining how society relies on these benefits. The Scottish Government report on Recognising the Importance of Scotland’s Natural Capital (2023) highlighted how different habitats in Scotland provide benefits to people over time, and contextualised metrics reported in the Natural Capital Accounts to understand their significance.

The 2008 Cambridge Econometrics study used SIC Codes (2003) to estimate the extent to which each of the 26 natural environment-dependent industry groups[13] in Scotland relied on and utilised the natural environment. Notably, it excluded abiotic services from the scope. While these sectors (e.g., mining and quarrying) rely on the use of the natural environment for primary resources, they represent a depletion of natural capital, rather than a use of ecosystem services.

The tourism and recreation sectors are traditionally highly dependent on nature, including in Scotland where the natural environment presents multiple areas of economic opportunities (as noted in the 2008 study). While tourism and outdoor leisure are not captured in national accounting, there are supplementary references and data sources for estimating relevant sectors’ reliance on nature as well as their contribution to the economy. The 2019 eftec-led study on tourism and outdoor leisure (T&OL) in the UK (disaggregated at the country-level, i.e. Scotland) provided estimates on the ecosystem contributions to T&OL activities as part of the development of UK Natural Capital Accounts. Furthermore, it disaggregated T&OL expenditure across different habitat and land cover types. As part of the 2021 UK Natural Capital Accounts update, the ONS published a set of T&OL accounts[14] that estimated that nature contributed £12 billion (in 2019) to T&OL across the UK, and £748 million (in 2019) to Scotland specifically.

More recently, and at the global level, the 2020 WEF report considered 163 economic sectors (and their supply chains) and assigned each sector an overall dependency rating across multiple ecosystem service and production process dependencies. The study approach was based on a methodology derived from PwC and the Exploring Natural Capital Opportunities, Risks and Exposure (ENCORE) tool for impacts and dependencies.[15] [16] The PwC methodology was subsequently updated in 2023 and accompanied by revised data points relating to natural capital reliance to derive new sector and global GDP reliance estimates.[17] The ratings process considered several factors, including:

- the degree of dependency of each ecosystem service on the relevant production process;

- the sensitivity of the production process to changes in the provision of the ecosystem service; and

- the sensitivity of financial performance to changes at production process level.

Box 2 : Detailed findings from the WEF 2020 Study

Using data from ENCORE and EXIOBASE, the report yielded several insights. Globally, the five most highly-dependent sectors on nature and its services (strictly measured through direct operations) were: agriculture; forestry; fishery and aquaculture; food, beverages, and tobacco; and construction.

Each of these sectors is determined to derive 100% of economic value by direct operations from nature, and collectively generate over US$13 trillion in economic value (approximately 12% of global GDP), with the construction sector alone accounting for US$6.5 trillion.

The PwC report identified eleven industries (i.e., water utilities; energy; chemicals and materials industry; supply chain and transport; automotive; digital communications; real estate; retail, consumer goods and lifestyle; aviation, travel, and tourism; mining and metals; and electronics) that have moderate or high dependence on nature (where at least 35% of its economic value is from direct operations and supply chains); as well as those industries with low levels of nature dependence in direct operations and supply chains, but higher levels of nature dependence downstream.

There are, however, limitations to the approach adopted in the WEF 2020 Study, as noted in the report itself as well as by other sources:

1. A Government of the Netherlands (2021) report noted that the analysis only considered first-order dependencies of economic sectors on ecosystem services, excluding those dependencies further up the supply chain.

2. The ENCORE tool risks missing potentially material ecosystem services as it omits those with lower materiality ratings.[18]

3. While primary industries’ reliance on natural capital is obvious, it may be less so for secondary and tertiary sectors which can also demonstrate significant reliance.

4. Certain industries (i.e., chemicals and materials; aviation, travel and tourism; real estate; mining and metals; supply chain and transport; and retail, consumer goods and lifestyle) have “hidden dependencies” on nature (as a proportion of their GVA) through their supply chains.

National Ecosystem Accounts Information from UN System of Environmental-Economic Accounting Ecosystem Accounting (SEEA EA) is another approach that can help to determine natural capital reliance at the national level in terms of material impacts and dependencies. SEEA EA is a multipurpose statistical framework for organising biophysical information regarding ecosystems. It tracks changes in ecosystem extent and condition over time, values ecosystem services and assets, and subsequently links this information to measures of economic and human activity.[19]

| Source title, author and year of publication | Key findings | Primary industries | Supply chain | Ecosystem services | Scoring assessment | Non-renewable services |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nature Risk Rising, World Economic Forum (2020) | US$44 trillion of global GDP (more than half) was moderately or highly dependent on nature and its services | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ |

| Managing nature risks: From understanding to action, PwC (2023) | US$58 trillion of global GDP (approximately 55%) was moderately or highly reliant on natural capital | √ | √ | √ | ||

| The Economic Impact of Scotland’s Natural Environment, Cambridge Econometrics (2008) | The estimated value of the natural environment to the Scottish economy was as high as £17.2 billion per year (based on type II effect – aggregation of direct, indirect and induced effects) | √ | √ | |||

| System of Environmental-Economic Accounting Ecosystem Accounting (SEEA EA), White cover (pre-edited version), United Nations et al. (2021) | √ | √ | √ | |||

| Exploring Natural Capital Opportunities, Risks and Exposure (ENCORE), UN Environment Programme World Conservation Monitoring Centre (n.d.) | √ | √ | √ | |||

| Biodiversity impact and ecosystem service dependencies, Government of the Netherlands (2021) | Assessment of direct dependencies provided valuable information on potential impacts, and the combined result of an impact and dependency profile can show the extent to which a company can influence ecosystem services it depends on | √ | √ | √ | ||

| The ecosystem contribution to tourism and outdoor leisure, eftec (2019) | Habitats with the largest contribution to T&OL activities are "coastal margin" and "marine"; T&OL expenditures for Scotland broken down by activity expenditure (£4,014 million), ecosystem attribution (£2,534 million) and ecosystem GVA (£1,169 million) | √ | ||||

| Assessing the Materiality of Nature-Related Financial Risks for the UK, Green Finance Institute (2024) | Scenario analysis by Green Finance Institute estimated that nature degradation 12% GDP loss to the UK compared to the business-as-usual baseline. | √ | √ |

Addressing the Challenges of Market Value Approaches

The desktop review highlighted a number of key challenges to measuring natural capital reliance in terms of an economic market value. The key challenges are:

- Traditional economic indicators may provide a limited view of natural capital reliance. Traditional economic indicators (e.g., gross domestic product (GDP), gross value added (GVA), and employment) do not capture non-market values of natural capital and ecosystem services. For example, the Scottish Natural Capital Accounts (2023) identified that health benefits from recreation were the third largest contributor to natural capital value in 2019 (at £725 million in 2021 prices). However, these estimates reflect the value of wellbeing and are not reflected in the system of national accounts.

- The market value of natural capital may not accurately reflect the relative importance of natural capital to an industry. The value of natural capital to production may be relatively lower than other products as inputs may not be priced or underpriced. For example, water is an important resource for food and beverage industries. However, an industry’s expenditure on water is a relatively small proportion of its total intermediate expenditure (less than 10%, according to 2019 Scottish Supply and Use Tables).

- The purchase patterns available may not be of sufficient quality to be used to estimate the reliance of Scottish industry on natural capital products, as some of these patterns are based on data that does not cover all industries. However, the Supply and Use Tables present the best estimate of these relationships.

- Scottish System of National Accounts data are a static representation of the economy in a given year and therefore cannot show how the economy 're-adjusts' to changes in natural capital.

This study sought to address these challenges by adopting an incremental approach to demonstrate the value of natural capital reliance within the boundaries of the SNA Supply and Use Tables. Using data from these tables as a basis, the study then applied a judgement-based approach and evidence-supported assumptions to capture the reliance of industry sectors.

The proposed approach drew on a selection of the quantitative and qualitative approaches to inform the methodology of this study, including the fundamental concepts of natural capital reliance both at the Scotland and non-Scotland (i.e., UK and global) levels.

Notably, the study methodology adopted a similar approach to that of the 2008 Cambridge Econometrics study with respect to (i) identifying the relevant SIC codes for natural capital reliant economic activities, (ii) apportioning the GVA of each of these SIC code-level sector to natural capital reliance, and (iii) determining the economic contribution of natural capital for each economic sector in terms of output and employment. Moreover, particularly for (ii), the WEF study from the New Nature Economy project took a similar approach to measuring the proportion of GVA that is highly or moderately dependent on nature as that which was used in this analysis.

Contact

Email: matylda.graczyk@gov.scot

There is a problem

Thanks for your feedback