Natural capital - importance to the Scottish economy: research

This research identifies sectors reliant on natural capital in Scotland and quantifies the economic value of these nature-dependent sectors at national and regional levels. The methodology values our economy's dependence on nature, estimating £40 billion economic output and 261,000 jobs supported.

Methodology

This section presents the methodology for developing the natural capital economic framework. It presents the overarching analytical framework and the approach to assessing the importance of natural capital and ecosystem services to industry in Scotland.

To measure natural capital reliance in terms of an economic market value (using the definition presented in Box 1), this study used three methods to identify sectors that are reliant on natural capital. Adopting Method 1 provided the narrowest definition of natural capital reliance, while Method 2 expanded on Method 1, and Method 3 in turn built on Method 2. More specifically:

i) Method 1: Identified industries that extract material and energy generated by provisioning ecosystems and calculated the role of natural capital in the economy using the input-output structure. This method provided the narrowest view of reliance on natural capital, but was also the measure most aligned to conventional statistics.

ii) Method 2: Expanded natural capital reliance to all other industries that purchase goods and services from industries identified in Method 1. An industry’s natural capital reliance was estimated as the proportion of its Scottish expenditure to goods and services from these industries.

iii) Method 3: Built on Method 2 by adjusting reliance on natural capital using expert judgement informed by external data sources. This provided the broadest view of economic reliance on natural capital. The expert judgements used have been referenced to supporting evidence where available, and were reviewed by the Project Team and the Steering Group.

The remainder of this section describes Methods 1-3 and the supplementary analysis in detail.

Method 1: Natural Capital Industries’ Output

This step of the analysis required a definition of ‘natural capital industries’ for analytical purposes. Natural capital industries were defined in this study as industries that supply materials or energy extracted from the environment to the economy, or ‘natural capital goods and services’.

Materials and energy generated by ecosystems (such as agricultural produce, timber and fish) were also referred to as provisioning ecosystem services, defined by the UN System of Environmental Economic Accounting: Ecosystem Accounting (SEEA EA). Mapping these provisioning services to SIC industries to identify natural capital supply-use relationships was a similar approach used to develop the ONS Natural Capital Supply and Use Tables, and the ecosystem service description in the tables was also adopted.

Industries were defined according to SIC industry classification from the 2019 Scottish Input-Output Tables. The analysis drew on the 2019 Tables instead of the latest Tables (2020), as the 2019 Tables more closely reflect the structure of the economy and industry relationships in 2024 (i.e., the 2020 data is likely to be more impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic).

With the exception of renewable energy (which only assumes a proportion of the industry based on renewable energy consumption), it was assumed that 100% of natural capital SIC industry products are reliant on natural capital. These industries reflect the direct extraction of resources from forests, arable landscapes and oceans (as per the definition of natural capital reliance).

A distinction was made in this analysis between renewable and non-renewable natural capital according to the definition from the Natural Capital Protocol:

- Renewable resources: resources that can be exploited indefinitely, provided the rate of exploitation does not exceed the rate of replacement, allowing stocks to rebuild (assuming no other significant disturbances). Renewable resources exploited faster than they can renew themselves may effectively become non-renewable, for example, when over-harvesting drives species extinct.

- Non-renewable resources: resources that will not regenerate after exploitation within any useful time period.

The Cambridge Econometrics 2008 study excluded non-renewable resources (e.g., oil and gas, coal and other minerals) on the basis that “they do not rely on or contribute to high quality environment”. However, recent developments in natural capital thinking acknowledge that the geophysical differences between non-renewable and renewable natural capital are often difficult to distinguish, and that non-renewable resources such as “power, salt and minerals are useful things that nature can provide” (CICES, p.5). For this reason, sensitivity analysis expanded the definition of natural capital products to include non-renewable goods. Table 2 shows the industry and provisioning services that can be directly mapped to SIC codes[20], and whether they are potentially renewable or non-renewable, (if the underlying asset is destroyed, it would no longer be renewable).

| Natural capital industry | Industry description | Renewable / Non-renewable | Provisioning service(a) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Agriculture | Production and harvest of plants and animals and support activities to agriculture, hunting and trapping | Renewable | Agricultural biomass |

| Forestry planting | Planting trees for timber production and forestry planting support services | Renewable | Timber removals |

| Forestry harvesting | Harvesting timber and harvesting support services | Renewable | Timber removals |

| Fishing | Marine and freshwater direct capture of seafood | Renewable | Fish capture |

| Aquaculture | Marine and freshwater farming of seafood | Renewable | Fish capture |

| Coal & lignite | Mining of hard coal (underground and surface) and lignite | Non-renewable | Fossil fuels – coal |

| Oil & gas extraction, metal ores & other | Extraction and mining of oil and gas | Non-renewable | Fossil fuels – oil & gas |

| Mining support(b) | Support service activities for the mining sector | Non-renewable | Other mining and quarrying products |

| Electricity | Production, transmission, distribution and trade of electricity | Renewable (53%)(c) | Renewable energy |

| Water and sewerage | Water collection, treatment and supply | Renewable | Water abstraction |

Notes: (a) Provisioning services[21] are used in the UK Natural Capital Account Supply and Use Tables. (b) Mining support is included to align with renewable industry definitions, which also include support services, and (c) Only a proportion of industry expenditure based on renewable energy consumption estimates from the Scottish Energy Statistics Hub is included as renewable.

The analysis reports domestic use expenditure by the natural capital industries, outlined in Table 2. These expenditure estimates represent industry totals. This industry expenditure estimate was converted to an output estimate the ratio total domestic expenditure to total output for each industry, which can directly be used to estimate wider economic effects of ‘natural capital’ and their supply chains.

Output is a broader measure of economic activity as it includes taxes, profits earned by businesses, salaries and wages and imports in addition to spend on other goods and services.

Method 2: Natural Capital Industries’ Expenditure

Building on Method 1, Method 2 included the industries most reliant on provisioning services (defined by the natural capital industries in Method 1), as an input to production. Method 2 determined the extent to which Scottish industries rely on the direct extraction of natural resources. This involved looking at natural capital SIC industry product expenditure as a proportion of total expenditure in other sectors.

Natural capital SIC industry expenditure was used as a proxy for total natural capital expenditure, in order to align with the production boundaries of the SNA. The ONS Natural Capital Supply and Use Tables adopted a similar approach to estimate sectors’ links to natural capital at the UK level and applies this to natural capital accounting data. The PwC 2023 study also used this approach to estimate the downstream supply chain dependence on natural capital.

Similar to the previous Cambridge Econometrics 2008 study, only domestic expenditure on provisioning services was included in the analysis for this study (i.e., it excludes imported forestry, fishing and agriculture products) to reflect the expenditure on Scotland’s natural capital only. The contribution of imports was therefore excluded in the calculation in this study.

A degree of caution should be noted when interpreting these results. The relationships underlying the data utilised purchases between industries from the Supply-Use tables to assign a proportion of an industry’s output as being ‘Natural Capital reliant’. This is the same dependency used to generate economic multipliers.

Additionally, the publicly available Industry by Industry Table used in this analysis, which contains information about domestic purchases, represents the relationship between industries purchasing from other industries – and the monetary flow to the sector – rather than the type of product. For example, an agricultural business supplying accommodation services would be captured as a transaction occurring in the agricultural industry, rather than accommodation and food services.

As in Method 1, the total domestic expenditure for each industry was converted to an estimate of output to estimate the indirect and direct economic impacts. In converting estimates of natural capital reliance from expenditure to output, an assumption was made that the natural capital reliance of salaries and wages, profits, imported goods and services and taxes were proportional to an industries domestic expenditure on natural capital.

Method 3: Measuring Reliance on Natural Capital Ecosystem Services

As previously mentioned, an industry’s expenditure on provisioning services may understate the reliance of natural capital as it does not reflect regulating and cultural services. To account for this, similar studies have used expert judgement to adjust quantitative estimates. For example, the ONS has used some judgement to determine which industries to include as intermediate consumers of ecosystem products.[22] The PwC 2023 study used a scoring system to capture the expert judgement process, rating industries from 1-5 based on the likelihood of a business within the industry failing financially as a result of ecosystem service disruption.

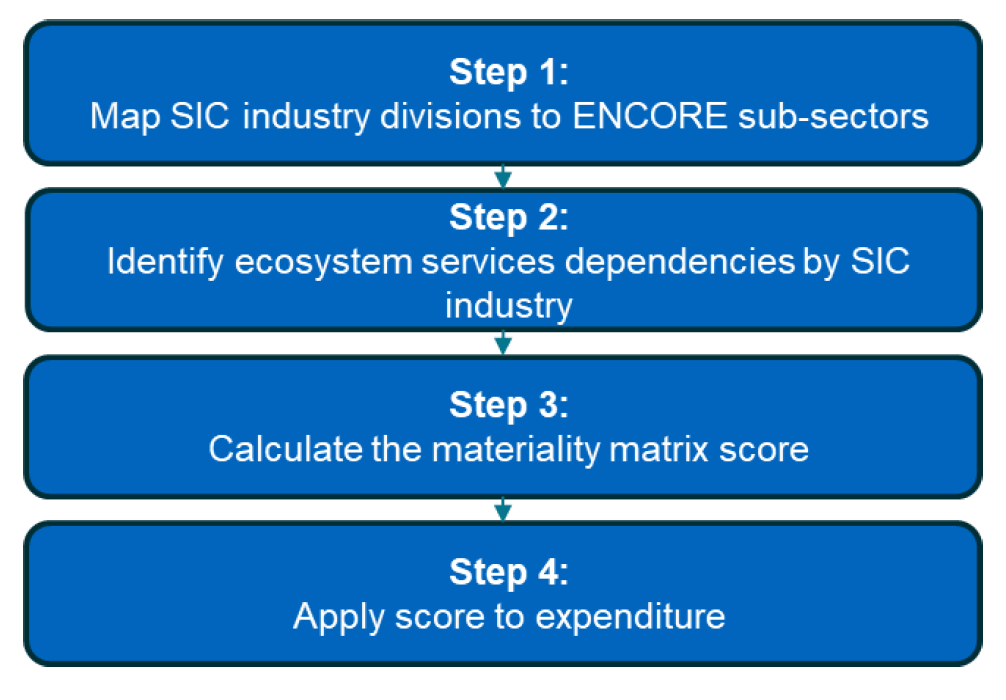

Method 3 built on Methods 1 and 2. It used a qualitative assessment of ecosystem dependence for each industry sector to estimate the industry expenditure that is reliant on Scotland’s natural capital, but is not exchanged as a provisioning service. The steps undertaken for this process are summarised in Figure 3 below and described below in further detail.

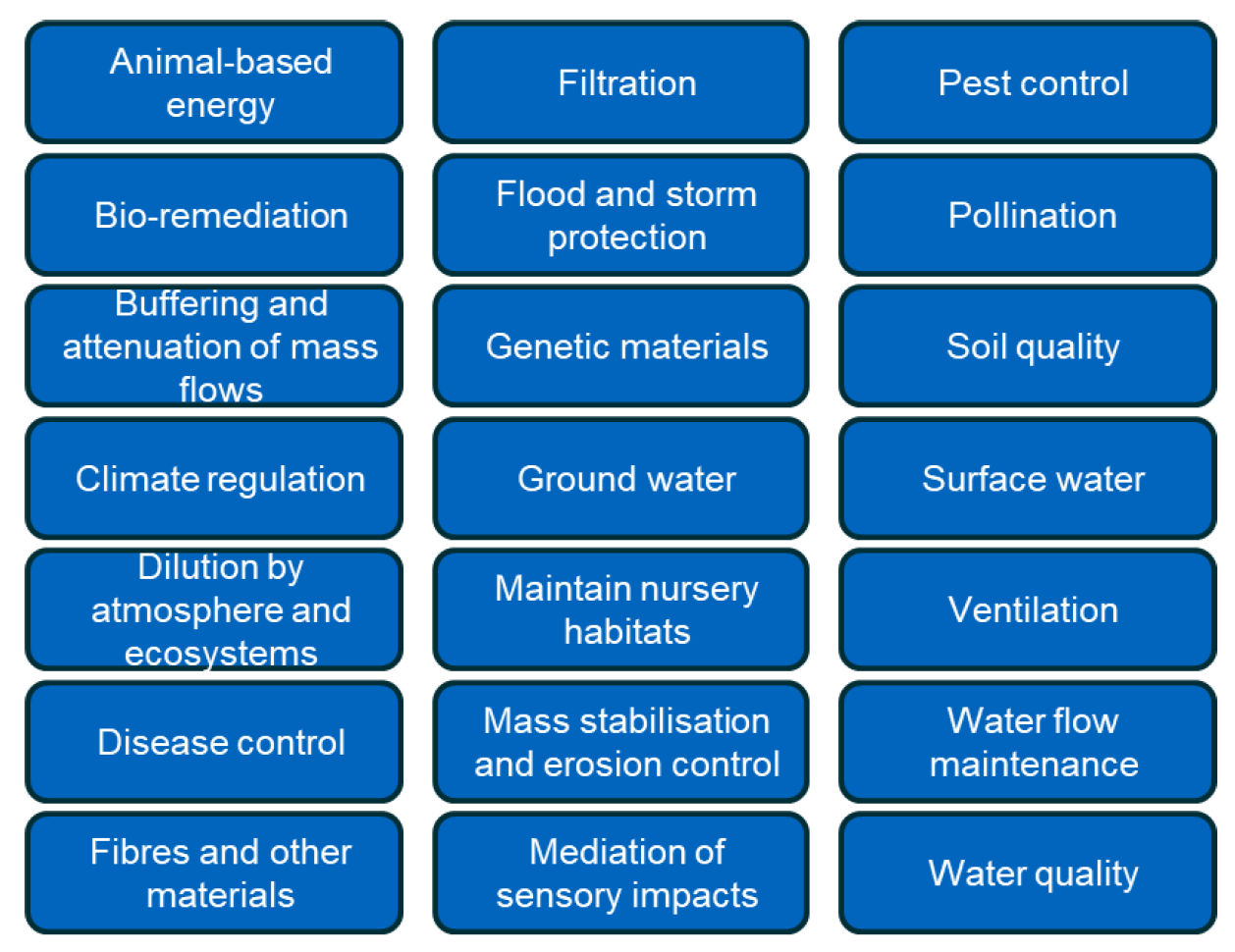

The first step to this method was to use the ENCORE[23] database to identify industry processes that rely on ecosystem services. This database identified 21 unique ecosystem services, outlined in Figure 4, and a full description of each ecosystem is provided in the Appendices (see Chapter ‘A1: Ecosystem Service Descriptions’).

The ENCORE database also identified 92 unique industry processes that are important for industry production in the economy, which in turn encompassed 152 sub-sectors in the ENCORE database. For example, the process of “alcoholic fermentation and distilling” was required for the “brewers” sub-sector and the “distillers and vintners” sub-sector. A total of 65 processes were unique to an individual sub-sector, such that “aquaculture” was the only industry process of the “aquacultural products” sub-sector.

For each industrial process, a list of ecosystem services dependencies was identified, representing the number of ecosystem services that are important for production. These ratings were determined through literature reviews and expert interviews with sector specialists, conducted by ENCORE.[24] For each relationship between an ecosystem service and an industrial process, a materiality rating of “very low”, “low”, “moderate”, “high”, “very high” indicated the extent that the ecosystem service was critical to the production process.[25] The ratings were converted to a score out of five, whereby “very high” represented a score of five.

Using this data, the Project Team then undertook a mapping exercise to align SIC industries to ENCORE sub-sectors on a “most-similar” basis, where some ENCORE sub-sectors could apply to multiple SIC industries. A total of 60 unique sub-sectors identified in ENCORE were mapped to the 98 industry SIC codes in the Scottish Supply-Use Tables, see Chapter ‘A2: Industry Mapping’ in the Appendices.

A qualitative diagnostic assessment evaluated the similarities of the match between SIC industries and the corresponding ENCORE code. This yielded the following results:

1. Two thirds of the SIC industries codes (66 SIC industries codes) were scored as being “highly similar”, and were considered a close match.

2. One third (32 SIC industries codes) were scored as “moderately similar”, where ENCORE defined the industry at a broader industry level compared to the SIC industry, but similar ecosystem dependency conclusions could be made.

This assessment concluded that ENCORE ecosystem service dependencies could reasonably be applied to SIC industries codes.

The second step used the SIC-to-ENCORE industry mapping to identify ecosystem services that were important to each SIC industry, and the extent to which they were important using the materiality rating. Mass stabilisation and erosion control was the most widely-used ecosystem service, where 86 industries depend on this ecosystem service to some extent. Ground and surface water (64 and 63 industries, respectively) and flood and storm protection (55 industries) were also considered widely-used ecosystem services across the economy.

The third step estimated a materiality score for each industry out of a maximum possible score of 105 (21 ecosystem services highly dependent on natural capital, i.e., 21 multiplied by five), converted into an index out of 100. Where there were multiple industry processes for one SIC industry (and hence, more than one ecosystem service dependency score), the highest ecosystem dependency score of the processes listed was assumed to be the ecosystem dependence score for that industry.

For some industry processes, a “high”, “moderate” or “low” rating was assigned to an ecosystem service, in part, because it was considered possible to substitute the ecosystem services for physical capital. For example, the ENCORE rationale for allocating a “moderate” ecosystem materiality score for flood and storm protection in the production of forest and wood-based products was “although less practical, production processes can take place without the ecosystem service due to the availability of substitutes”.[26] An experimental approach used this rationale as a basis to apportion the materiality index into a “substitutable” proportion of ecosystem dependence and a “non-substitutable” proportion of ecosystem dependence for each industry (for further explanation of substitutability approach, see Appendix 3). Only the substitutable proportion of this index was used in the economic impact analysis.

The fourth and final step applied these indices to industry expenditure estimates from Method 2, which represents an experimental order-of-magnitude estimate of ecosystem service dependence that is additional to what is captured in the System of National Accounts. This industry expenditure estimate was converted to an output estimate for each industry using the same expenditure to output ratios applied in Methods 1 and 2.

Tourism and Outdoor Leisure Activities

Tourism and outdoor leisure activities (T&OL) is also a key economic sector that relies on the natural capital. However, it is recognised as a combination of industries in the national accounting framework. A detailed approach developed by eftec estimated the economic contribution of nature tourism and outdoor leisure activities to the UK economy by region, including to Scotland. This approach is described in the eftec report, and can be summarised according to four steps:

1. Collecting tourism and outdoor leisure activity data from a range of sources including the GB Day Visitor Survey (GBDVS) (for trips of more than 3 hours) and the GB Tourism Survey (GBTS) (for domestic, overnight visitors);

2. Dividing this expenditure across T&OL activities;

3. Attributing these activities to specific ecosystems, including the proportion of expenditure that is dependent on natural capital and physical capital; and

4. Apportioning the total ecosystem service expenditure value to SIC expenditure categories, identified using the tourism satellite account.

Further details on the methodological steps can be found in Appendix A4.

Overall, the result of this process was an estimation of the proportion of attributable tourism expenditure that was dependent on ecosystem services by type of activity. The expenditure was aggregated across all activities and distributed to the eight UK-TSA tourism industries, which include: accommodation for visitors; transport; food and beverage industry; cultural industry; sports and recreational industry; transport equipment rental; travel agencies and other services industry; and meetings and conference industry.

Scottish Government identified sustainable tourism as a key growth sector in Scotland’s Economic Strategy (2015). The sustainable tourism growth sector defined in the strategy represents a subset of tourism industries used in this study. The industries used in this analysis broadly align with the industries used to define Scottish sustainable tourism, shown in Table 3.

| Tourism industry used in this study | Sustainable tourism growth sector |

|---|---|

| Accommodation for visitors | SIC 55.1: Hotels and similar accommodation |

| Accommodation for visitors | SIC 55.2: Holiday and other short-stay accommodation |

| Accommodation for visitors | SIC 55.3: Camping grounds, recreational vehicle parks and trailer parks |

| Food and beverage serving industry | SIC 56.1: Restaurants and mobile food service activities |

| Food and beverage serving industry | SIC 56.3: Beverage serving activities |

| Travel agencies and other reservation services industry | SIC 79.12: Tour operator activities |

| Travel agencies and other reservation services industry | SIC 79.9: Other reservation service and related activities |

| Cultural Industry | SIC 91.02: Museum activities |

| Cultural Industry | SIC 91.03: Operation of historical sites and buildings and similar visitor attractions |

| Cultural Industry | SIC 91.04: Botanical and zoological gardens and nature reserve activities |

| Cultural Industry | SIC 93.11: Operation of sports facilities |

| Cultural Industry | SIC 93.199: Other sports activities (not including activities of racehorse owners) |

| Cultural Industry | SIC 93.21 Activities of amusement parks and theme parks |

| Cultural Industry | SIC 93.29: Other amusement and recreation activities |

It is important to note that the estimates derived from this approach to the tourism sector used a different source of data and a different ecosystem dependency approach to Method 3 applied for the rest of the analysis. Therefore, updated tourism expenditure estimates for Scotland were included in this analysis but were not aggregated with Method 3 results. Using this approach, it was estimated that £2.1 billion in domestic T&OL expenditure can be attributed to natural capital in 2019 (see Table 4).

This expenditure was apportioned to UK Tourism Satellite Account (UK-TSA) industries, which align with UK industry. To align this approach with the approach used in the eftec study, this only accounts for domestic tourists’ expenditure and does not account for overseas expenditure.

| UK-TSA Tourism Industry | Expenditure (millions) |

|---|---|

| Accommodation for visitors | £125 |

| Transport | £566 |

| Food and beverage serving industry | £820 |

| Cultural industry | £225 |

| Sports and recreational industry | £42 |

| Transport equipment rental | £28 |

| Travel agencies and other reservation services industry | £44 |

| Meetings and conference industry | £0 |

| Other* | £225 |

| Total | £2,075 |

Note: *Other industries included expenditure items from the GBDVS and GBTS surveys that are classed as "Other Consumption Products", or items also overlap with tourism industries that have been missed in the UK-TSA (2016).

Workforce Health

Workforce health in the context of natural capital reliance was also considered in this analysis, although it was not explicitly measured or captured in the approach as a natural capital benefit. The interaction of multiple ecosystem services, particularly between regulating services (e.g., temperature regulation and air pollution removal ecosystem services), can potentially explain changes in workforce productivity given that health benefits arise from a combination of factors relating to the natural environment. Where there was sufficient evidence for Scotland (as in the case of air pollution), the analysis identified a number of relevant components relating to air pollutant concentration, sick days, and employment that can be linked to estimate the value of air pollution changes on workforce productivity in monetary terms.

Reliance on natural capital to support workforce health was not captured in Methods 1-3 above. The method development effort in this study was focused on Methods 1-3, and therefore did not address the methodological issues in measuring and calculating industry-level reliance on natural capital health benefits. However, workforce health (and population health, more broadly) can have significant effects on the economy, namely through GVA and GDP (i.e., a healthier population reduces healthcare expenditure, thereby freeing up public and private budgets while encouraging more active participation in society and the economy). The key variable of interest is workforce productivity, and therefore it is recommended as an area of further study. Further details on the methods and analysis can be found in the ‘Workforce Health’ sub-section of the following ‘Economic Impacts of the Various Methods to Measure Natural Capital Reliance’ chapter.

Contact

Email: matylda.graczyk@gov.scot

There is a problem

Thanks for your feedback