Inequalities in access to blue coastal space: research report

Research report exploring factors affecting people’s access to coastal space in Scotland.

2. Review of previous research

The rapid literature review provides an overview of the current knowledge base relating to the research questions. Specifically, it covers:

- Evidence about the benefits of access to coastal blue space;

- Existing knowledge about inequalities in access to coastal blue space;

- What good practice examples exist of policy solutions or initiatives that have been used in other countries to improve access to coastal blue space; and

- Which data sources could be used as an indicator for access to blue space.

The review focuses on inequalities in access to coastal blue space rather than use of blue space in general. However, it also incorporates relevant learnings from research dealing with inequalities of access to green space (under the second question outlined above) and where green and blue space are researched together.

Benefits of access to blue space

Evidence has accumulated rapidly in recent years demonstrating the substantial population health and wellbeing benefits of access to natural environments, often referred to as 'green and blue spaces' (Geneshka et al., 2021; Twohig-Bennett and Jones, 2018). Much of the research has focused quite generically on 'green/blue space' or 'nature', but there is now a substantive body of evidence on blue space, and particularly coastal environments (Gascon et al., 2017; White et al., 2020).

Coastal communities experience a range of challenges to their health and wellbeing, such as poor housing and access to services (CMO, 2021). However, evidence based on England Census data shows that after accounting for levels of socio-economic deprivation and population age, those living closer to the coast typically report better health than those more inland (Wheeler et al., 2012). Importantly, it is also suggested that these benefits may be stronger in more socio-economically deprived communities, indicating that benefits associated with coastal living may to some extent ameliorate health inequalities (Garrett et al., 2019; Wheeler et al., 2012).

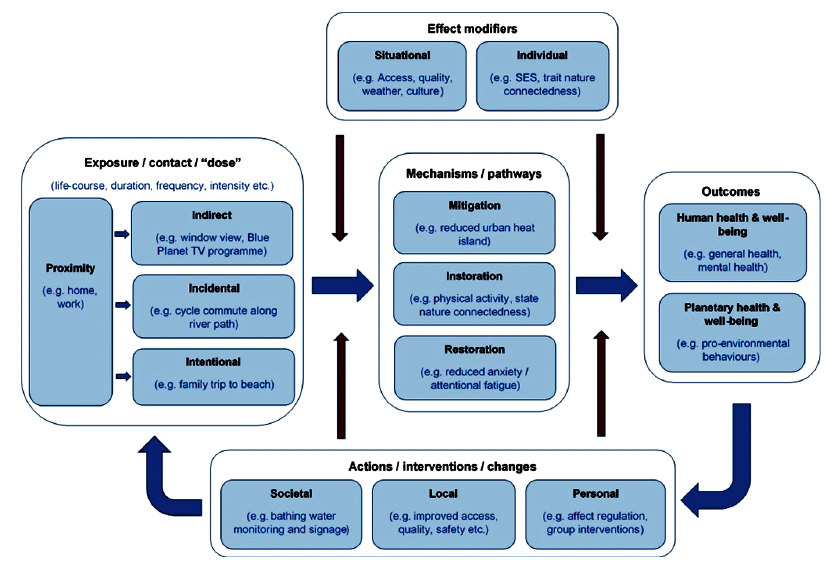

Passive or active exposure to 'nature' is proposed to result in benefits for health and wellbeing through a number of pathways. These pathways have been summarised as (Markevych et al., 2017): building capacities (e.g. support for physical activity and social contact); restoring capacities (e.g. recovery from stress) and reducing harms (e.g. mitigating noise and heat). Again whilst these pathways have been developed generically, they capture the ways in which access to coastal blue space can lead to health and wellbeing benefits (Georgiou et al., 2021; White et al., 2020). Figure 1 summarises the pathways from blue space to health and wellbeing, including indicating how these relationships may be modified (for example by socio-economic status) and how different kinds of actions may influence the pathways.

Reproduced under CC-BY license from White et al., 2020.

Whilst some benefits of coastal blue space do arise through passive pathways (e.g. mitigation of excess heat in coastal urban areas), this summary focusses on the benefits of time spent on actual visits to these environments. Much of this access is recreational and associated with intentional visits, although some is also more incidental such as commuting routes that pass through blue spaces. However, there is very limited evidence on the benefits of these more incidental interactions (White et al., 2020) and the evidence here primarily relates to intentional access to blue spaces, primarily coastal, and drawing upon evidence relevant to Scotland's coastal environments and communities.

Firstly, blue spaces provide both opportunity (usually freely accessible space with amenable environments such as paths, beaches, open water) and motivation (e.g. aesthetics, perceived restorativeness) for people to be more physically active, a critical determinant of numerous physical health conditions and mental health and well-being. Living near to, and spending time in, coastal blue spaces has been demonstrated to be associated with higher levels of physical activity (White et al., 2014). Importantly, most active visits to these environments are not for more high impact activities (e.g. swimming, surfing), but for walking (Elliott et al., 2018), one of the most common ways in which 'everyday' physical activity can be gained for a large proportion of the population (NHS Scotland, 2022) (note that access and disabilities are discussed below). Analysis of the Health Survey for England has shown that walking is a key mediator of the health benefits of living in proximity to coastal blue space (Pasanen et al., 2019), and a study using the same data estimated the health economic value of physical activity in marine environments in England at £176m/year (Papathanasopoulou et al., 2016).

Secondly, blue spaces, particularly coastal environments, can promote good mental health through support for subjective wellbeing and stress reduction. These are some of the key mechanisms proposed for the linkage between time spent in natural environments and mental health (Markevych et al., 2017), and there is some evidence that blue spaces may be particularly beneficial in this regard (White et al., 2020). A recent review on behalf of an EU programme found multiple types of evidence to support positive impacts of blue space visits on mental health and wellbeing, with most of the evidence arising from the UK and concerning coastal blue space (Beute et al., 2020). Evidence from Scotland indicates that populations living closer to coastal and other blue spaces typically have lower rates of antidepressant prescribing (McDougall et al., 2021).

The third key pathway to health benefits is how blue spaces may promote social contact. While a recent review of the mechanisms for benefits did not find clear quantitative evidence that social interaction mediates the blue space-health relationship (Georgiou et al., 2021), several qualitative studies in the UK, Ireland and Germany have indicated the importance of these environments for people to spend quality time with friends and family (Ashbullby et al., 2013; Bell et al., 2015; Foley, 2015; Volker and Kistemann, 2015). Additionally, survey data for England indicate that social interaction is a key motivation for visits to beaches and other coastal environments, and to a greater extent than it is for inland blue space, urban open space or woodlands (Elliott et al., 2018).

The Covid-19 pandemic illuminated and emphasised the value of access to green and blue spaces to support health and wellbeing, especially through these key pathways (Pouso et al., 2021; Stewart and Eccleston, 2022). One study, in Belgium, specifically explored the value of coastal environments during Spring 2020, and found coastal residents to report greater happiness and less boredom and worry than inland residents, although there were no associations with actual coastal visit frequency (Severin et al., 2021). Qualitative research in the south west of England on the coast as therapeutic landscape during the pandemic highlighted how people's relationships with the sea changed during this time, and the potential importance of 'homely' coastal encounters as part of everyday life for coastal residents (Jellard and Bell, 2021).

Whilst the focus here is on the benefits of access to coastal blue spaces, it is acknowledged that access also poses some risks to humans. Coastal environments present a range of hazards, including the potential for drowning and other accidents, flooding and dangerous weather conditions, and the potential for exposure to water contaminated by sewage or other pollution. However these hazards can and should be mitigated (e.g. (Scott et al., 2022)), and should not detract from the benefits that may be gained from safe access to good quality coastal environments.

Inequalities in access to blue space

Access and accessibility

There is relatively limited evidence on inequalities in access to blue space specifically. However, there is evidence that more socio-economically deprived areas typically have lower availability of good quality public green/blue space (based on a systematic review including studies from UK, Germany, France, Finland, Portugal (Schüle et al., 2019)). Further, evidence from England and Scotland indicates that people who make visits to nature infrequently (or never) are more likely to be: female, older, in poor health, of lower socio-economic status, from an ethnic minority group, living in socio-economically deprived areas and lower green space neighbourhoods (Boyd et al., 2018; Stewart and Eccleston, 2020). These same sources indicate that the reasons why infrequent nature visitors say they do not visit more often are primarily to do with personal/social circumstances rather than a lack of physically accessible natural spaces, including lack of time at home/work, poor health and 'old age' (Boyd et al., 2018; Stewart and Eccleston, 2020).

It is therefore important that individual, social and structural barriers are considered alongside availability of/proximity to blue space when aiming to address inequalities in access. Behaviour change frameworks can be used to help structure approaches to access; for example, the MAPPS framework has been used in NatureScot work previously (Scottish Government, 2021). Interestingly there is some evidence from England suggesting that social/structural inequalities in accessibility to coastal blue spaces may be somewhat more equitable compared to those for natural environments more generally. These survey data indicate that, for example, visits to beaches are more likely to be made by women, older age groups (35-64 vs 16-34) and some lower socio-economic groups. This was contrasted with, for example, a strong socio-economic gradient in woodland/forest visits being much more likely amongst people in higher socio-economic groups (Elliott et al., 2018).

Access domains

Despite these complexities of access and accessibility, physical proximity is still an important driver of recreational visits to green/blue spaces. In one study using data from the Scottish Household Survey 2013-19, frequency of visits to the nearest local green/blue space was strongly associated with self-reported walking time to that space. 87% of people reported living within a 10 minute walk of their nearest green/blue space (a significant threshold given policy interest in the '20 minute neighbourhood'), but those within a 5 minute walk were 53% more likely to visit at least once a week compared to people living 6–10 minutes away (Olsen et al., 2022). In terms of blue spaces, an international survey found that individuals living closer to the coast based on map distance were more likely to make frequent visits (at least once a month), with an exponential relationship between distance and probability of frequent visits. For example, those living within 1km were around twice as likely to make frequent visits as those living 1-5km away, and those twice as likely as people living 5-10km away (Elliott et al., 2020).

These studies highlight the relevance of both objectively measured proximity (e.g. distance from home) and perceived distance (e.g. self-reported walking time). This is an important consideration, since map distance is important for understanding potential accessibility, but people's propensity actually to make visits may be more likely to be influenced by their perception (including both perceived distance and perceptions of local transport networks, public transport links etc.). For example, a systematic review of associations between neighbourhood environment measures and physical activity found that perceived environment measures were more strongly associated with activity than objectively measured environment characteristics (Orstad et al., 2016). Further, a study investigating proximity to green spaces in Glasgow found poor agreement between perceived and objectively measured distance, with some suggestion that the level of agreement was lower amongst people from lower socio-economic groups (Macintyre et al., 2008). Perception of water quality may also impact frequency of visits to blue space, as suggested by a pan-European survey (Börger et al., 2021), and environmental qualities more broadly are likely to be important.

As indicated above, a range of individual, social and structural conditions and circumstances affect the accessibility of coastal blue space. Physical infrastructure (or lack of it) has a significant impact on accessibility for many people in several different ways. General evidence on greenspace accessibility highlights for example the importance of toilets, benches and path networks, which may be more important for people with disabilities or older people, for example (PHE, 2020). Qualitative research in the UK specifically on visual impairment and experience of coastal blue space demonstrated the importance of both physical and social accessibility, but also to be wary of assuming that making coastal environments accessible and appealing for individuals with visual impairment requires removal of all risks (Bell et al., 2019). This work has more widely led to the development of guidance on inclusive design and walking groups to promote and support access to nature (Bell, 2018).

A review on engaging people from ethnic minority backgrounds in nature flagged how racism, unwelcome visibility and being made to feel 'out of place' have fundamental impacts on accessibility. It also raised the importance of acknowledging diversity within groups, relevant for any work aiming to improve accessibility for particular groups of the population (Rishbeth et al., 2022). While in a very different context, research in the USA specifically focused on access to beaches, and found significant contemporary ethno-racial inequalities grounded in historic, structural discrimination and racism (Phoenix et al., 2020). Qualitative research in Scotland explored a range of drivers of participation in outdoor recreation, and also revealed a range of issues particularly pertinent for many people from ethnic minority backgrounds, such as the importance of cultural norms and circumstances (Scottish Government, 2021).

Environmental justice and links with health inequalities

Work on environmental justice has typically focused on environmental hazards, but applies just as well to access to health promoting environments, including coastal blue spaces. It makes clear the importance of considering not only 'distributional injustice' (e.g. inequalities in accessibility of blue spaces), but also 'procedural injustice' (e.g. processes, policies, laws that lead to these inequalities) and 'recognition injustice' (e.g. the exclusion of individuals, communities their knowledge and experience in determining actions and outcomes) (Mitchell, 2019). When considering inequalities in access to coastal blue spaces and their benefits, these complex structural and system considerations are therefore relevant in understanding and tackling those inequalities. In this context it is also important to recognise that some processes of environmental improvement may lead to undesirable social outcomes, particularly potential gentrification (the process of changing the character of a place through the influx of more affluent residents and businesses). This can have adverse impacts, especially upon residential affordability (Anguelovski et al., 2022).

There is evidence suggesting that access to good quality green/blue space may help to mitigate socio-economic health inequalities to some degree ('equigenesis' (Garrett et al., 2019; Mitchell et al., 2015)). Considering this in combination with the evidence above on inequalities in access suggests that there may be a 'win-win' scenario whereby decreasing inequalities in access could potentially lead to disproportionate benefit for those communities and individuals who have most to gain. Interventions that improve access for all, but are suitably targeted, would be consistent with the concept of 'disproportionate universalism' in addressing health inequalities (Marmot et al., 2010), with the proviso that unintended exacerbation of inequalities (e.g. through gentrification), can be avoided.

While significant benefits of access to nature were observed during the Covid-19 pandemic, it also served to emphasise inequalities in access to natural outdoor environments, including blue spaces. Evidence indicates that older people, those in poor health and those in lower socio-economic groups were more likely to actually reduce their time spent on visits to natural environments during periods of restrictions (Burnett et al., 2021; Stewart and Eccleston, 2022).

Policy solutions in other countries

This section outlines a set of policy interventions and solutions from other countries and regions that may help to improve access to coastal blue space. As discussed in the first section of this review, existing evidence has shown that significant health and social benefits can result from exposure to blue spaces (Geneshka et al., 2021; Hanley et al., 2021; Twohig-Bennett and Jones, 2018; Wheeler, White et al., 2012). In this context, public authorities and practitioners in many countries have developed policy solutions and interventions that aim to enhance safe access to blue spaces (White et al., 2020).

We draw on a categorisation model developed by White et al. (2020) as a way of classifying blue space policy solutions and interventions. The framework divides interventions into societal actions, local and regional actions and personal actions:

- Societal actions are defined as structural solutions that enable greater access to blue spaces, such as improving transport links to the coast or improving bathing water quality;

- Local and regional actions seek to augment the blue spaces themselves, by, for example, developing waterfront promenades or coastal cycle lanes;

- Personal actions include projects that incentivise the use of blue spaces (rowing or swimming clubs, for example).

Policy action and associated research agendas on coastal blue spaces typically focus on risks to humans and their mitigation (e.g. EU directives on bathing water quality, shellfish waters and surface waters) (Borja et al., 2020). As described elsewhere, policy and other interventions on recreational access to natural environments for health and wellbeing typically focuses on 'green space' or 'nature' generically. There is therefore an opportunity to bring these arenas together to promote and support the potential health and wellbeing benefits of safe access to healthy coastal blue space (Fleming et al., 2021).

Societal actions

Policymakers in a range of countries have implemented structural solutions that help to enable greater access to blue spaces. These include:

- In England, the landmark Marine and Coastal Access Act 2009 (UK Government, 2009), which mandated the creation and maintenance of accessible walking routes along the majority of England's coast. The policy targeted a 2,800-mile-long coastal path with the explicit objective of increasing public exposure to the coast (White et al., 2020). This increased recreational access would be expected to lead to increases in opportunity for physical activity, and mental health and wellbeing improvement in the context of the evidence summarised above.

- In Scotland, reforms that enable greater personal actions in respect of blue space use. Since the introduction of The Land Reform (Scotland) Act 2003, citizens in Scotland have a statutory right to responsible use of blue spaces. It established the right to non-motorised access to most inland water throughout Scotland and set out the extensive duties of local authorities to uphold access rights, including for people with disabilities.

- In several national and multilateral contexts, including the EU, the USA, the UK and New Zealand, management of water quality is one critical component of enabling public use of blue spaces. A prominent water management policy was the EU Bathing Water Directive (EU, 1976). The measured quality of bathing water across EU member states rose significantly in the decades following the legislation's introduction; meanwhile, public use of these bathing waters increased substantially (White et al., 2020 ). Through the development of comprehensive water management systems, societal actions in the USA (the American Best Management Practices), New Zealand (the Low Impact Development system), and the UK (the Sustainable Urban Drainage System) have indirectly enabled blue space access for decades (Scholz, 2006). In Scotland, the Scottish Environment Protection Agency (SEPA) routinely monitors and publishes the chemical conditions of Scotland's freshwater bodies in order to support the River Basin Management Plan process and ensure the sustainable public use of the water environment.

Local and regional actions

A comprehensive review of local blue space interventions found 172 successful policy examples that improved access to coastal waters (Bell, 2019). Several of the interventions were intended to enhance the aesthetic quality of the space (making it more appealing to tourists and locals) and/or to facilitate physical exercise (for example, by building walkways or cycle lanes in and around blue spaces). Other examples included the conversion of former docks into recreational areas, building waterfront promenades, and improving the quality of and access to local bathing waters.

Local and regional actions within a group of countries (USA, Denmark, Poland, Sweden, Colombia, UK, France) shared broad themes:

- Lighting up promenades, docks or other coastal infrastructure at night

- In England, the promenade at Whitley Bay has been lit up to encourage dog walking, cycling and walking at night.

- Renovating waterfronts

- In Poland, a smooth wooden deck was constructed along the Paprocany Waterfront, where blue hammock nets were installed for users to relax with lake views.

- Elevated viewpoints and blue-facing seating

- Sweden's Sjovikstorget project involved the building of a belt of wooden stepped seating along the water's edge overlooking the open plaza.

- In Denmark, the augmentation of the Amager beach area included building elevated viewpoints along sections of the promenade.

- Facilities (e.g. gyms, kayak centres) in surrounding area

- The 'Berges de Rhone' development (2007) was a project undertaken by the city of Lyon, which transformed a riverside car park into a multi-functional public space. Facilities constructed along the river include a swimming pool, sports centre, refreshment kiosks, cycle hiring and fishing facilities.

- Integrating walking and cycling paths with blue space

- England's Marine and Coastal Access Act (2009), referred to earlier in this section, requires public bodies to create paths for walkers all around the English coast.

England's Environment Agency, alongside Natural England, has recently initiated a raft of local and regional blue space policies. These include collaborations with Tideway, who are developing additional public spaces to bring London's inhabitants and tourists closer to the River Thames than is currently possible.

Pan-European research initiative BlueHealth ran from January 2016 to December 2020 and aimed to "provide evidence-based information to policymakers on how to maximise health benefits associated with interventions in and around aquatic environments" (Grellier et al., 2017). The initiative's researchers drew attention to the statistically significant positive effects on wellbeing and life satisfaction (which held when controlling for relevant variables) that resulted from the recent regeneration of an inner-city beach in Plymouth. Infrastructure improvements in the proximity of Plymouth's blue space included an open-air theatre and a children's playground, while coastal wildflowers were planted to improve the aesthetics quality of the area. Before and after surveys, along with before and after behavioural observations, were used to track the public's response to the new site (BlueHealth, 2020, p.26).

BlueHealth has developed an environmental assessment tool to assess the quality of coastal environments. This is intended for use by local governments to help them maximise these spaces and determine the most impactful interventions in terms of promoting the health of local communities (BlueHealth, 2020).

In England, Manchester City Council and the Irwell Rivers Trust recently embarked on a large-scale development to restore public footpath access to sections of the River Medlock: a project hailed as exemplary by the European Union. Indeed, revitalising run-down natural assets can be an effective means of unlocking the potential health benefits offered by blue space environments (Smith et al., 2021).

However, Kabisch et al (2016) caveats this approach, arguing that if revitalisation of existing blue space occurs within a wider context of gentrification, then this could be distributionally counterproductive since it would further exclude the most disadvantaged groups. Haase et al (2021) and Raymond et al (2017) found that upgrading blue space displaces low-income residents by enticing richer households to the area. Indeed, a study analysing house prices in the Netherlands found a strong positive correlation between the value of a house and the extent to which that house was exposed to blue space (Luttik, 2000).

Personal actions

Personal actions involve projects that facilitate the use of blue spaces by specific individuals (for example, water sports clubs). Kabisch et al. (2016) found that such community-led programmes, which encourage use of urban blue spaces for physical exercise, enjoyment, or socialisation, may enhance urban public health more effectively than top-down (societal) interventions.

Individual-focused interventions have been branded variously as 'blue care' or 'the Blue Gym' (Depledge and Bird, 2009), and are being deployed with increasing regularity (Britton, 2018). 'Blue care' refers to structured programmes or activities taking place within a natural water setting, targeting individuals with defined needs, to alleviate illness or promote mental and physical wellbeing for that group (Britton et al., 2018).

In a systematic review, Britton et al (2018) examined 33 of these individually-focused programmes in countries including the USA, Canada, Portugal, Israel, the UK, New Zealand, and Italy. The authors studied only programmes that were structured for therapeutic purposes. They found that programmes were generally targeted at those with defined needs, including: post-traumatic stress disorder (e.g. among army veterans), breast cancer, cognitive impairments, and complex mental health issues. Surfing was the most popular intervention activity, followed by dragon boat racing, sailing, kayaking, and fishing. Approximately half of the interventions occurred in coastal waterways, with the other half occurring in inland water areas.

The systematic review by Britton (2018) found little evidence that the interventions improved physical health. However, there was some evidence for increased social connectedness during the programs. The review concluded that a wide range of blue care personal action initiatives delivered substantial benefits for both mental health and social well-being. One notable example was the delivery of a kayaking program for 129 inner-city economically disadvantaged children in Jacksonville, Florida. Tardona (2011) evaluated the impact of the programme by collecting qualitative evidence from the programme instructors (who also happened to be trained psychologists). He found that child well-being – as observed by the psychologists – near-ubiquitously improved between the start and end of the program.

Similarly, Vert et al (2020) found that an intervention to promote walking in and around Barcelona's seafront yielded positive effects for walkers' mood and overall wellbeing.

Further policy suggestions

Beyond existing policy solutions and initiatives, a host of practical policy recommendations have been forthcoming from researchers. Many of these relate to the urban environment, where space can be at a shortage. Langie et al (2022) suggest incorporating 'micro-blue spaces' (such as wading fountains) or repurposing vacant and derelict land as blue space. Smith et al (2021) highlight the merits of granting public access to private spaces, as has been implemented to some degree in Scotland.

Recommendations from Mishra et al (2020) involve the use of blue space environmental assessment tools to inform policymaking (such as those designed by BlueHealth). These could combine self-reported user assessments of blue spaces with objective surveys undertaken by trained environmental auditors. Such assessment tools could measure the cleanliness, aesthetics, safety and accessibility of blue spaces; and could therefore be used to inform the decisions of local authorities and planners when evaluating existing blue spaces. They might also be turned into citizen science initiatives to educate local communities (Jansson & Randrup, 2020).

Findings from Jansson & Randrup (2020) suggest that in terms of maximising benefits for existing populations, policies which facilitate community governance of blue spaces may be more useful than policies which simply seek to improve the quality of blue spaces.

While the focus was on urban green space, a key finding from a systematic review of the environmental, health, wellbeing, social and equity impacts of interventions was that the best results across these multiple domains are likely to arise from integrated actions. These aim to make changes to physical environments to improve and promote access and appeal, alongside social interventions such as educational and promotional programming (Hunter et al., 2019). These findings have influenced an action brief from WHO on urban green space, and are likely to also have relevance to the coastal blue space setting when considering actions.

Data sources that could be used as an indicator for access to blue space

As part of Marine Scotland's monitoring of the Blue Economy vision[1], an indicator to measure access to coastal blue space (separately from green space) is required. This section considers which data sources could be used for this indicator/s.

There is currently a data gap on access to both coastal blue space and blue space more generally in Scotland:

- The Scottish Household Survey (SHS) has been used since 2016 as the data source to monitor progress on the Scottish Government's National Indicator on access to green and blue space, which forms part of the indicator set for Scotland's National Performance Framework. This indicator of access to green and blue space is based on measuring the proportion of adults who live within a 5-minute walk of their local green or blue space, and does not split out green space from blue space.

- Scotland's People and Nature Survey (SPANS), conducted on behalf of NatureScot in 2013/14 and 2017/18, includes questions about coastal visits (% who have gone to 'the seaside (a resort or the coast)' in the last four weeks for leisure and recreation, what type of location/destination they visited (e.g. loch, sea/ sea loch, river, canal, beach, cliff, etc).

- The Covid-19 Recreation Survey, three waves of which were conducted in 2020 and 2021, also included questions about outdoor visit behaviour during the past four weeks, including coastal blue spaces such as the sea/ sea lochs, beaches or cliffs.

Also relevant is The People and Nature Survey for England, which has questions about free time spent outside in green and natural spaces, including any visits to the coast and activities in the open sea. The survey asks about visit frequency to green and natural spaces, types of green and natural spaces visited in the last month (including 'beach/ other coastline/ sea'), whether the quality of the green and natural spaces close to where the respondent lives has improved, reduced or not changed in the last 5 years, and about what they think green and natural spaces should be like as well as what the green and natural spaces close to where they live actually are like.

Three important considerations when developing an indicator for access to blue space include:

1. How access should be defined. We recommend that the focus should be on actual access (i.e. those who have visited the coast in the last 12 months) rather than potential access (i.e. those who would be able to access the coast but may or may not have done so in the last 12 months).

2. How proximity to coastal blue spaces should be defined and captured. Existing research often defines coastal proximity as living less than 5 kilometres from the coast. Proximity can be measured based on postcode data, as long as postcode is collected as part of the survey. Another option is to measure perceived distance to coastal blue space; for example, the Scottish Household Survey indicator of access to green and blue space is based on self-reported walking distance. For the question set fielded for this research, both options were used to enable the research team to look both at perceived and actual proximity to the coast.

3. How usage/non-usage are defined and captured. For example, SPANS uses the following categories of visit frequency to the outdoors: frequent visitors (those who visit once a week or more often), occasional visitors (those who visit once or twice a month), those who visit seldom (once every 2-3 months, or once or twice a year), and those who never visit the outdoors for leisure or recreation.

Data sources that could potentially be used in future for an indicator of access to coastal blue space are:

- Placing question/s on an existing survey, such as Scotland's People and Nature Survey or the Scottish Household Survey

- Placing question/s on an omnibus survey. Options include random probability panel surveys and standard opt-in online panel surveys.

The decision on which data source should be used will depend on a range of factors, including methodological quality, frequency, timeliness of results and available budget.

Contact

There is a problem

Thanks for your feedback