Inequalities in access to blue coastal space: research report

Research report exploring factors affecting people’s access to coastal space in Scotland.

5. Barriers and enablers to accessing the coast

Key Points

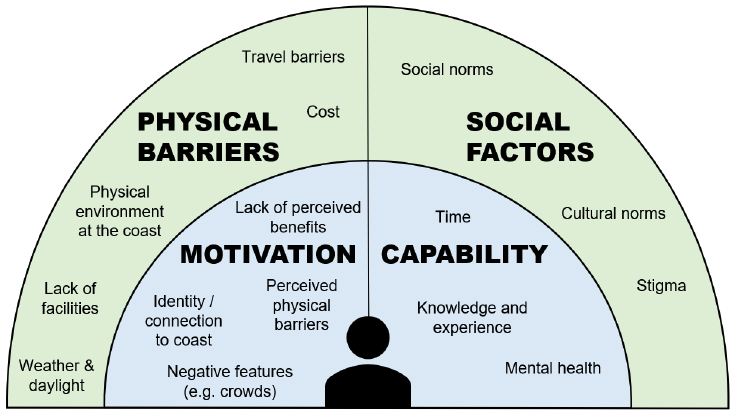

- There were a wide range of reported barriers that stopped participants from visiting the coast more often, or at all. These can be broadly grouped into the following categories: motivation, capability, physical barriers and social factors.

- Motivational barriers had a considerable impact on participants not visiting the coast. These included personal preferences and not seeing the benefits of spending time at the coast. However, there were also features of the coast that actively put participants off visiting such as overcrowded beaches, experiences of anti-social behaviour, or beaches not being clean.

- Other factors which could affect motivation to visit included participants' personal identity and feelings of connection to the coast, as well as perceived barriers (expectations about how easy or difficult it would be to get to the coast).

- Two main factors limited participants' individual capability to visit the coast; namely having the necessary knowledge and experience or a lack of time. There were also those for whom their state of mental health limited their ability to go out in general.

- Physical barriers to spending time at the coast came out strongly. Participants cited travel barriers (primarily relating to public transport), travel costs, challenges interacting with the physical environment at the coast such as sandy beaches or eroded paths, and a lack of good quality facilities. Weather and daylight hours also played a role.

- Social and cultural norms were another important factor that shaped participants' experiences of, knowledge of and attitudes towards visiting the coast. When participants were unaware of friends or family visiting the coast, or others in their community doing so, this made them less likely to consider going themselves. Among ethnic minority participants, there were some reported concerns about stigma and feeling uncomfortable at the coast.

This chapter addresses the second research question, namely what the key factors are that affect use of the coast amongst different people and groups. As the research focuses on the experiences of infrequent visitors to the coast, this section explores the barriers to visiting, but also covers factors that acted as enablers where relevant. It draws primarily on the data from qualitative interviews and group discussions as well as some quantitative survey data (on perceived distance from the coast).

In line with the literature review findings, a range of barriers emerged during qualitative fieldwork with infrequent visitors to the coast. This chapter is structured using the MAPPS behavioural framework which breaks down individual barriers into those relating to 'motivation' (do participants want to visit the coast?) and to 'capability' (do participants have the capacity to visit the coast?). These are outlined in detail, before being followed by a discussion of the physical and social/cultural barriers to spending time at the coast.

Figure 13 below provides an overview of the barriers and enabling factors identified from thematic analysis of the qualitative data. Each of these is then discussed in turn.

Motivational ('do I want to do it?')

Motivational barriers had a considerable impact on participants not visiting the coast. These included personal preferences and a lack of 'pull factors', as well as features of the coast that actively deterred participants from visiting. Personal identity and connection to the coast also played a role, as did perceived barriers (negative expectations about how easy or difficult it would be to get to the coast). Finally, weather and limited daylight hours in the winter months affected participants' motivation to visit.

Personal preference and lack of 'pull factors' to visit

As outlined in the previous chapter, participants generally had positive associations with the coast. When they did visit, they were motivated to do so for various reasons, often depending on personal circumstances and individual preferences. Therefore, when particular parts of the coast did not facilitate the kinds of activities or experience participants were looking for, this could be off-putting. For example, coastal areas which were perceived as more 'industrial' were typically less appealing to visit as they lacked the aesthetic landscape and views that could draw people to the coast. For participants who enjoyed visiting local coastal amenities such as cafés or arcades, a lack of these (particularly during the winter when many are closed) made them less keen to visit.

Linked to this was a view that there can be a lack of things to do at the coast. One stakeholder found that in their experience, the young men they worked with in particular seemed to prefer hill walking as they liked to do something challenging or goal-orientated, which was not something they associated with the coast. To illustrate:

"I would choose a woodland or a hilly area over a beach every time given the choice. […] I've got more something to do, like if I'm walking up a hill or something and if I have got a goal and then I feel like I had a workout or something like that. Whereas walking along the beach is just like walking along the street but a bit nicer."

(Male participant, 16-34)

Perceived negative features of the coast

In addition to the lack of 'pull factors' mentioned above, participants also discussed things they did not like about the coast which actively deterred them from going. These were largely related to the presence or behaviour of other people at the coast, including: overcrowding; safety and anti-social behaviour; littering and cleanliness; and the presence of dogs (which divided opinion).

Participants tended not to enjoy spending time at the coast when it was very busy, as it could be unrelaxing or stressful. This was typically associated with beaches and especially in the summertime. For those who went to the coast to feel calm and relaxed, these wellbeing benefits were directly diminished by crowds and this could also present significant barriers for those with anxiety. Participants had previously left beaches that felt too crowded or avoided going in the first place if they suspected it would be too busy.

"Definitely in the summer or if there is a bank holiday weekend and everybody is at the beach, I find that really off-putting. It is […] an anxiety thing, a claustrophobic feeling, not wanting to deal with so many people. So, yes, I think how popular certain beaches are can make them difficult [to visit]."

(Female participant, 16-34)

"With large groups of kids or just gatherings in general, I think I would probably avoid it, and I think a lot of people who have like social anxiety would feel pretty similarly."

(Male participant, 16-34)

There were some worries discussed around personal safety at the coast, primarily around anti-social behaviour although one participant mentioned being afraid of the sea. Concerns ranged from people drinking and being 'rowdy' at the coast, to more dangerous behaviours such as throwing bottles or even the presence of gangs and related violence. Portobello beach in Edinburgh was an example of a beach that participants felt could be unsafe. Worries around experiencing anti-social behaviour could particularly put people off visiting the coast alone or with children.

"They were just rowdy and they were just throwing bottles everywhere and all that and the little one got a bit frightened, and I'm like, you know what, it's just not worth it."

(Female participant living in deprived area in Edinburgh/Lothians)

Coastal areas not being clean could also deter people from visiting or spending as much time at the coast as they would like. Participants described beaches that had litter on them as well as over-filled bins.

"There is quite a lot of litter as well, particularly at Portobello, which is rotten to go out and spend some nice time amongst nature just seeing like bottles and alcohol bottles, and packets and wrappers everywhere, It almost defeats the point of being in a nice, serene space."

(Female participant living in deprived area in Edinburgh/Lothians)

While poor water quality was not generally seen as a major issue in Scotland, there were participants for whom this had been off-putting. This was usually an issue for particular areas of the coast, for example one participant described avoiding a particular beach due to concerns about pollution from nearby industrial sites. It was typically more of a barrier for those who wanted to swim in the sea, and one stakeholder who took people on organised trips to the coast recalled cancelling plans to go wild swimming when it was felt that the water was not clean enough.

Opinion was split over the presence of dogs at the coast. While there were participants for whom being able to take a dog to the coast was an important factor in encouraging them to go, or who found the presence of dogs appealing, others did not like dogs or were frightened of them. Participants had also experienced issues with dog fouling on the beach. There was a view among those with dogs that more clarity was needed about which parts of the coast it is permissible to take dogs to, to help both themselves and other visitors at the beach feel at ease.

Identity and connection to the coast

Perceptions of identity and how connected participants felt to the coast also played a role in how much they wanted to visit. For example, when participants were asked if they associated the coast with certain 'types' of people, families with children and dog walkers came out strongly. This could make people who did not fit into these categories feel less comfortable about visiting. This was particularly discussed by young people aged under 35, with one participant saying they did not feel like the coast was somewhere where 'single professionals' usually went.

"I feel like I stick out a little bit on a beach because I'm not there with a dog and I'm not there with a child, I'm just me by myself. So I think that is why I more avoid those places now."

(Female participant, 16-34)

There was a view among stakeholders working with ethnic minorities in Scotland that there can be a perception that the coast is a 'White space' which is not as diverse compared to cities, and that it is not typical for ethnic minority groups to visit. While the impacts of social influences are discussed later on, it was suggested that these feelings could contribute to a general sense that people did not see themselves as the type of person that visited the coast.

Furthermore, participants did not tend to describe feeling a sense of personal connection to the coast. While this was not explicitly discussed as a barrier, it was clear that among those who did feel a connection to the sea or the coast this increased their motivation to visit. This was typically built up as a result of positive experiences and familiarity with the coast, especially when participants had previously lived nearby. Once formed, this type of connection tended to be strong and enduring and motivated participants to return to coastal areas.

"I find I have to go and get my sea-fix every now and again. Though I wasn't actually brought up as a child by the sea, I think once you've lived by the sea you've always got that hankering to go back."

(Disabled female participant, 65-74)

A stakeholder highlighted that for ethnic minority communities, there may be less of a familiarity with the coast in cases where people in these communities or their relatives had moved to Scotland more recently. There was a suggestion that first generation immigrants in particular may be more focused on other priorities, for example work or establishing themselves in a new place, and less on leisure time. However, this could then contribute to a lack of connection to the coast for second or third generation immigrants as well if they did not spend time there growing up.

"That kind of gets passed down to us as well […] determined by what was of interest from the people before you […] and I think that's why I don't go [to the coast]."

(Female participant from a Black African background, 16-34)

Perceived barriers to accessing the coast

While participants described potential external barriers that limited their ability to visit the coast, there were cases where the idea of possibly coming across barriers (rather than the barriers themselves) could deter people from attempting to visit in the first place. This typically related to avoiding potential transport issues such as cancelled trains or delayed buses, but participants also described being hesitant to risk a long journey to the coast if it turned out to be unpleasant once they got there (for example being overcrowded). One participant highlighted that this risk aversion was made worse by the fact that it was not easy to travel between beaches and spread out to another part of the coast if your original destination felt too busy.

"I would like to go more, but I think it is about kind of knowing that once you get there you are going to be able to have a nice, relaxed time and not be surrounded by other people."

(Female participant living in a deprived area in Edinburgh/Lothians)

"[To] not have anywhere to stop [to park] and have to find somewhere else to go, that kind of inconvenience would make us think twice about going to the coast."

(Male participant, 16-34)

A stakeholder who worked with disabled people pointed out that, while they felt there was a lot of information available about the accessibility of various areas on the Scottish coastline, this was not always easy to find. In their experience, much of this information was only available online which excluded those who were not comfortable searching for information this way. They also described doing a 'recce' themselves to determine whether certain routes were fully accessible, but imagined that many people would not want to do this themselves.

"[Not knowing if a route is accessible] It will put a lot of people off. A lot of people need to know where they're going and what they're able to achieve and they don't want to come across these barriers and have to turn back."

Stakeholder (Disabled Ramblers)

One participant suggested that although they had a perception of the coast as being difficult to visit, in reality it was probably easier than it seemed:

"I think objectively it is really easy for me to get to the coast, but then sort of subjectively, it feels like more of an effort to go to Portobello than to go to other places."

(Male participant, 16-34)

Ability('am I able to do it?')

Two main factors limited participants' individual capability to visit the coast; namely having the necessary knowledge and experience and a lack of time. Mental health could also limit participants' ability to go out in general.

Knowledge and experience

Among participants who had not had much experience of visiting the coast in Scotland, there was a sense that they did not know exactly how to go about this. For example, participants mentioned not knowing which areas of the coast would be nice to visit or accessible, how to get there and back, what sort of facilities would be available or what to do there. While participants described having been inspired to visit some beaches after coming across images on television or social media, there was a sense that it was challenging to seek out this information. For example, it was not always felt to be clear which coastal areas were nice to visit from looking at a map.

"I always wonder if there are maybe coastal areas which are conveniently, like quite close to me that I'm maybe not entirely aware of. […] I do wonder sometimes if I am missing out on a hidden gem there."

(Female participant living in a deprived area in Edinburgh/Lothians)

There was a view among ethnic minority participants and stakeholders working with these groups that information was a key barrier for their communities. This related both to being less likely to have spent time at the coast themselves and not knowing others who went (more detail on this is outlined in the social barriers section below). This could mean that, apart from knowing where to go or how to get there, they did not have a sense of basic practical information such as how long is an ideal amount of time to spend at the coast or what people typically do there.

Lack of time

A lack of time to plan and carry out a trip to the coast came out as a key barrier, particularly for those working or studying full-time or those with childcare or other caring responsibilities.

"There's nothing stopping me other than life."

(Disabled male participant, 55-64)

This intersected with travel barriers, as travel time and issues with public transport could make it difficult for participants to fit in visiting the coast with other plans or commitments before or after, and could mean that effectively they felt they needed to block out an entire day to visit the coast.

Mental wellbeing and energy levels

Individual capability to go out could be affected by participants' mental state and energy levels. Those with health conditions or disabilities were particularly likely to face barriers in this regard, both as a result of physical conditions (such as ME) or suffering from poor mental health (such as depression or anxiety).

One Muslim participant highlighted that when fasting during Ramadan, they and the wider Muslim community have less energy and are less able to go out and do things, including visiting the coast. As the dates of Ramadan change each year, they felt this had a particular impact in years when it takes place during the summer, when people would otherwise be more likely to want to go to the beach.

Physical ('does the context encourage the behaviour?')

Participants discussed various physical barriers that made it difficult for them to visit the coast, including: transport infrastructure; transport costs; the availability of facilities; the physical environment at the coast; the behaviour of other visitors; cleanliness and water quality; and the weather and limited daylight hours in winter.

Distance from the coast

Naturally, the distance participants lived from their nearest coastal area played a role in how likely they were to visit.

"To me it is just about proximity, I think, because you can't just pop there because it is just not close enough, even a train or a car can only go so fast. […] If I lived closer to the coast, I would just go a lot more."

(Female participant living in a deprived area in Glasgow)

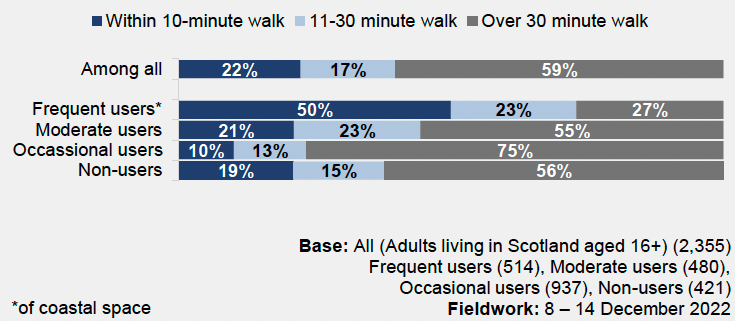

This is supported by the data from the general public survey which asked about how far away their nearest public coastal space was. Notably, there was a positive relationship between perceived distance from the coast and being a 'frequent user' of coastal space (Figure 6). However, for non-users of the coast there was a higher proportion of participants living within a 10-minute walk of the coast compared to occasional users, suggesting other barriers (unrelated to transport) were more relevant among those who did not choose to visit the coast at all.

Q: How far away from your home is the nearest public coastal blue space?

Travel barriers

Travel barriers emerged as a strong theme among participants that did not live within easy walking distance of their local coastal area. While most travel barriers related to the use of public transport, challenges with driving or walking to the coast also came up.

A variety of issues with public transport provision were discussed, centring on convenience, availability, and cost. While these barriers were mainly relevant to those who did not have access to a car, one participant who travelled to the coast by car felt that a better train service would encourage him to visit more often as he would prefer taking the train to driving a long distance.

Public transport was typically viewed as a slow way to access the coast, especially buses in comparison to driving. While off-putting in itself, a longer journey also cut into the time participants were able to spend at the coast, making a visit seem less worthwhile. The time-consuming nature of public transport could also exacerbate other issues, for example making a trip to the coast more of an 'event' which would take up a whole day, with the extra planning and costs associated with a daytrip. One participant explained that taking the bus to the coast would take so long that they felt they would have to stay overnight before returning. This was contrasted with visiting green spaces, and one participant described spending time more 'passively' passing through local green spaces compared to taking a more intentional and pre-planned approach to visiting the coast.

"For me it involves like buses, trains, it would be an entire day. You would have to take money for food and everything like that."

(Female participant, 16-34)

Participants had experienced infrequent, inconveniently timed or unreliable public transport which made it more difficult to plan a trip to the coast or making certain areas inaccessible at particular times of day. When transport wasn't running in the evening, this also cut into the amount of time people could spend at the coast and prevented them staying for a whole day. This, combined with the perceived unreliability of transport links, prompted concerns about getting 'stranded' at the coast and being unable to get back home. Wanting to visit the coast with people who did not live in the same place could create additional logistical challenges with matching up timetables and routes.

"You've got to plan it a bit more. If you can't just jump in the car you've got to work out timetables and so on and if it doesn't match up, that's a bit of a barrier."

(Female participant living in a deprived area in Glasgow)

"If I want to go to a quieter place, it would require changing buses a bunch. […] It means that I'm kind of locked into going to Portobello and I can't really explore."

(Female participant, 16-34)

There was an acknowledgement that some coastal areas do not have any public transport links, limiting which parts of the coast people can visit and 'funnelling' people into the same areas. For example, one participant thought it would be challenging to access more secluded parts of the coast which were more "off the beaten path". Another participant highlighted that the lack of transport connections between coastal areas made it difficult for them to access the coast in an enjoyable way due to not being able to visit a different part of the coast easily if their original destination turned out to be too crowded.

There was also a view that spending time on a bus can be unpleasant, particularly in warmer weather (which is when participants tended to be more likely to want to visit the coast). For participants who had to change buses or trains, this meant extra hassle, time and often cost due to needing multiple tickets.

By contrast, having a car was typically seen as an enabler to visiting the coast, since it gave participants the freedom to choose exactly when and where they wanted to go. However, those that drove reported experiencing different kinds of barriers, such as difficulties finding suitable parking. A lack of parking space could make popular beaches less accessible for those driving to the coast generally, although a stakeholder believed this was particularly relevant to those with mobility issues who typically need to drive to the coast and may require a larger car park if they use a ramp to get in and out of their vehicle. One participant with a disability also highlighted the importance of disabled parking areas near to the beach, as walking was difficult for them.

"There were no car parking spaces when we went there., they were all full, there was a small pay car park and people were parking away up the road as well. So, I think the busier beaches, the most popular places, can be hard to get to by car."

(Male participant, 16-34)

Among participants who cycled, this was often a way they would like to access the coast, but there were concerns around a lack of cycle lanes or secure bike storage.

"With Edinburgh in particular, the lack of secure bike storage at the beach [is a barrier]. Like I would go on my bike, but I would never leave my bike. Which means that I could never then go into businesses, so I wouldn't want to take my bike down".

(Male participant, 16-34)

There were participants who felt their beach was within a reasonable walking distance for them, however external factors that could make walking difficult or less appealing included unpleasant routes (for example busy roads) or unsafe routes.

Transport costs

There were participants for whom the cost of public transport, especially trains, was prohibitive. There was a belief that this was getting worse, due to increasing prices and the cost of living crisis. Notably, this barrier came out strongly in discussions among participants living in more deprived areas. Participants also suggested that cost barriers would be especially relevant for families paying for multiple tickets.

"It would be a very costly experience, especially like when you're talking probably about £20 just in transport for myself, never mind the rest of my family."

(Female participant, 16-34)

Pen portrait 2 – Alistair

Alistair lives in Glasgow and runs his own business. Lately he's been having some financial difficulties. He enjoys walking his dog in local parks, although he would like to go for dog walks at the coast if it was more affordable for him.

"I think if money was no object, I would go most days, because it would just be nice to go on big long walks with the dog and go somewhere different, you know? As it is I just go to all the parks in Glasgow."

ScotRail being unreliable is another barrier, as Alistair is concerned about the possibility of trains being cancelled or delayed, which could leave him and his dog stranded at night. Since he is unable to drive, he relies on public transport to get around.

In Alistair's experience, the time commitment required to plan and execute a trip to the coast is off-putting.

"You have to pretty much block out like a whole day for it, most of the day, based on where we are."

Alistair indicated that a cheap monthly train pass could make him more likely to visit, and that if he had a car he would visit much more often.

There was also a belief that getting to the coast was more expensive than visiting other outdoor spaces.

"There is not much difference saying you want to go to the coast to saying you want to go up to the Highlands and just walk about on the hills, […] but it is the cost of getting there, or the friction of getting there".

(Male participant living in a deprived area in Glasgow)

Costs associated with driving, including parking charges and the rising price of fuel, could also stop people from visiting particular coastal areas.

"Last year, the cost of petrol was high so that was a barrier to doing things. […] I wouldn't take long trips because it was costing too much to fill the tank."

(Disabled female participant from an Asian background, 45-54)

The physical environment at the coast

Something that was unique to the coast were features of its physical environment such as sand, rocks and the sea. In some cases, the topography of the coast could pose difficulties for participants, particularly when they had a health condition or disability.

Firstly, while there were participants who specifically sought out sandy beaches, sand could pose significant barriers to those with mobility issues. For example, sand could be tiring for people to traverse and make it difficult or impossible to use a wheelchair. Even when wheelchair users are able to use a beach wheelchair (adapted for use on sand), a stakeholder highlighted that these can't be motorised and people are then reliant on having somebody else with them and cannot visit the coast independently.

More generally, sand was perceived as inconvenient as it stuck to clothes, could be blown into people's faces or food, and there were participants for whom the feeling of sand could make them feel uncomfortable, especially when there are no walkways or promenades to walk on. One participant highlighted that this was a problem for them specifically due to having a health condition which made them particularly sensitive to tactile stimuli. Sand was also seen as a difficulty for families with children, due to being unable to easily use a pushchair and concerns around children getting sand in their mouths and eating sand.

A stakeholder who supported disabled people to spend time in nature explained that coastal erosion could make paths along the coast more challenging to use on a motorised mobility scooter, and when sand blew over paths this could be dangerous. The windy weather at the coast could also pose a threat: one stakeholder recalled a time where the wind at the coast had caused somebody's mobility scooter to overturn. Narrow paths, paths with a camber or inaccessible gates had also been known to cause difficulties.

Other concerns about the physical environment included the timing of the tides; the build up and smell of seaweed; and issues with coastal wildlife, specifically seagulls harassing people and trying to take their food.

Lack of good quality facilities

Participants described how a lack of good quality facilities at the coast could sometimes be a barrier to spending extended time at the coast, specifically: access to toilets, indoor spaces, food or drink, or, for Muslim participants, an appropriate space to pray.

Lack of toilets was mentioned as a difficulty, particularly for people with a health condition or disability. A stakeholder highlighted that people with mobility issues may also require larger toilets or ones with rails and other adaptions to make them accessible to use, limiting them further. One participant whose mother had dementia explained that they would be unable to go to a beach without a toilet. A stakeholder that works with people with disabilities pointed out that this can be a particular issue at the coast compared to green spaces, due to being unable to set up temporary natural toilets which need to be far from bodies of water. Putting up a tent could also be more challenging on the open, often windy, coastline.

"If you need the toilet and you are there visiting in November, you've got a choice of walking back up to the main road at Portobello or the sea."

(Female participant, 16-34)

There was also a desire among certain participants for nearby indoor spaces such as cafes in order to take shelter if the weather became cold or particularly windy or wet. Again, it was felt that this was particularly important for those with disabilities or additional needs. The availability of facilities could therefore mediate the impact of concerns about accessing the coast in periods of colder weather, however participants pointed out that availability of coastal facilities can be seasonal, meaning access to facilities is typically more of an issue in the winter months.

There were participants for whom the ability to purchase affordable food or drink as important in making a visit enjoyable (food was often a positive association with the beach, particularly on holiday, for example ice-cream or hot dogs).

Availability of food could be a particular barrier for Muslim participants, who said it is difficult to find halal food options outside of Scottish cities. However, there was a view that the community may be more likely to bring their own food to deal with this.

Finally, one Muslim participant described the difficulties she had experienced on a previous trip to the coast when trying to find an appropriate space to pray (which she did five times every day). Difficulties included having a clean space that was large, clean and private enough to pray. The last time she was at the coast she had prayed in her car, but this was not ideal and she had felt uncomfortable doing so.

Weather and daylight

There was widespread acknowledgement that the weather and limited daylight hours in winter have a significant impact on the experience of visiting the coast.

While there were participants who would prefer not to be outside at all during cold or wet weather, there was some evidence to suggest that bad weather could be particularly impactful for people's decision to visit the coast compared to other outdoor spaces. Firstly, there were widespread associations of the coast with the sun and warm weather, and of visiting during the summer holidays. One participant who grew up in Holland and did not experience childhood holidays at the beach reflected that they may be more likely to visit the coast throughout the year in part because they had not built up this association.

"I'd rather take a walk around the field, far away from water, in the winter. The coast for me is sunshine, relaxation."

(Male participant from a Black African background, 45-54)

"The connotations of the coast always have to do with summer so it's kind of like you limit your access. […] The way it's advertised is 'be there in the summer, don't go when it's not sunny' kind of thing."

(Female participant from a Black African background, 16-34)

However, there was also a view that the coast still has something to offer in cold or windy weather, with participants mentioning that the landscape was still "beautiful" and that the sea could be interesting to watch. In fact, one participant felt that bad weather is less off-putting for them when it comes to visiting the coast compared to green spaces, since it feels more of an 'event' in itself.

"I think when it is rainy and cold, I'm probably less likely to go to a park because then the park seems not enough of an event, I guess, so I won't got there necessarily. Whereas going to the beach, even when it is quite grey and blowy, like it feels a bit bracing. It is quite nice sometimes."

(Female participant, 16-34)

There was a sense among ethnic minority participants and stakeholders working with these groups that the weather could be an important factor for these communities in particular, especially when participants or family members had links with countries with warmer climates, making Scotland's climate seem particularly cold in comparison. One participant from a South Asian background mentioned a belief in their culture that visiting the coast can cause people to get ill easily due to the cold.

"[My wife and I] like it more with the warmth, the water is cold. […] I can't get used to it, I wish I could."

(Male participant, grew up in Niger Delta, 45-54)

Finally, there was reference to limitations imposed by daylight hours, mostly during the winter. This could limit the amount of time participants felt comfortable spending at the coast or even make it difficult to go in the first place for those who were working or had other commitments during the day.

"In the warmer months, maybe once every two to three weeks, I tended to try and make an effort on a Sunday to get out and [walk to the coast]. But, yes, as soon as it is dark outside it's like 'nah'."

(Male participant, 16-34)

Social ('what do other people do and value?')

Social and cultural norms were an important factor that shaped participants' experiences of, knowledge of and attitudes towards visiting the coast.

Social norms

There was evidence to suggest that social norms played a role in participants' likelihood to visit the coast. Participants who visited the coast more often (albeit still infrequently) tended to know others in their social circle or wider community who enjoyed visiting the coast, while those who visited less were more likely to say they didn't. Knowing others who enjoyed visiting the coast was particularly important given the fact that participants tended to prefer visiting the coast with company.

While there were young people (aged under 35) who knew people that went to the coast regularly, there was a view among this group that people their age might prefer to do other types of activities. Social norms and not seeing or hearing about other people visiting the coast was also seen as a particular barrier for ethnic minority groups among ethnic minority participants and stakeholders.

"I would say that I can't off the top of my head think of anyone my age that goes to the beach regularly […] at least they don't mention it."

(Male participant, 16-34)

"I think most our age would probably think of going […] for a holiday somewhere else together instead of, like, going to the beach here in Scotland."

(Male participant, 16-34)

"As someone that comes from a Pakistani background, it just wouldn't pop into the discussion 'ok, why don't we go to the coast?' […] and I feel like that is mainly to do with your ethnicity and the culture that you've been brought up in."

(Participant from an Asian background, 16-34)

Cultural factors

Ethnic minority participants highlighted various cultural factors which affected how easy it was to incorporate visiting the coast into their lifestyle and routines. These were echoed by stakeholders that worked with these groups.

There were examples of cultural activities that were not seen as fitting well with visiting the coast. A participant from a Pakistani background felt that in their culture, food was an important part of going out and socialising but the coast offered fewer opportunities to do this or access the kind of food or drink they wanted.

"You tend to go for food in our culture, being able to share nice meals is a special thing. But I feel like in the coast there are fewer people like us so there would not be restaurants that offer the food we like, also because we don't eat pork or drink. So the options are more limited, we cannot participate.""

(Male participant from a Pakistani background, 16-35)

Intersectionality between groups was highlighted, including barriers specifically for women in minority ethnic communities. For example, a stakeholder from an Asian background felt that within their community, people typically valued having single-sex spaces or activities. Women in his family would not feel comfortable swimming in an open, public space, while a Muslim participant highlighted that due to dressing modestly in line with her cultural and religious beliefs, she was not interested in activities typically associated with going to the beach such as sunbathing.

One participant though people who had recently moved to Scotland may be more likely to visit areas that they felt more interesting and 'unique' to Scotland.

"People from my ethnic background will choose Loch Lomond over the actual coast […] because Loch Lomond is more unique to Scotland."

(Female participant from an Asian background, 16-34)

A participant from a Black African background said that in her experience, people in the Black community were less likely to swim, which could reduce motivation to go to the coast. She also pointed out that it could be especially inconvenient for her and other Black women to get their hair wet.

"You won't find a lot of black girls going to the beach, a lot of it has to do with our hair. […] You don't really wanna go to the beach 'cos like, you know, you've got your braids and you don't want to ruin them because you've paid a lot of money."

(Female participant from a Black African background, 16-34)

Social stigma

Both stakeholders and minority ethnic participants explained that for people in their communities, there could be additional social barriers due to a perceived lack of diversity at the coast, causing concerns around feeling uncomfortable, being stared at or experiencing racism. One stakeholder stressed the importance of being able to see people 'like you' and from your community at the coast to feel comfortable.

"The moment people see other people in the community smiling having a good day out, they want to be part of it."

Stakeholder working with ethnic minority communities

They also highlighted that there may be cultural differences in how people from different communities want to interact with outdoor spaces. For example, they recalled a group of young Asian men out in the countryside playing loud Punjabi music and having a BBQ, and that this may not be socially acceptable to others.

Pen portrait 3 – Yasmin

Yasmin is a Pakistani woman in her forties, living in Glasgow. She has lived with long-term health conditions for a number of years as well as being a single parent to her daughter. Although she has some positive associations with visiting the coast in Scotland, there are lots of different kinds of barriers that get in the way and she hasn't been for the past five years.

For Yasmin, key benefits of being at the coast are the calming atmosphere and spending time in nature. However, being at the coast can also cause her anxiety. Since she is afraid of dogs, Yasmin worries about coming across them at the beach. In bad weather the coast itself can be also be scary, and Yasmin recently cancelled a trip to the Isle of Skye in November as she felt the weather would be too unpredictable and the daylight hours too short to make it enjoyable.

As a Muslim, Yasmin has experienced additional challenges including a lack of halal food options or suitable places to pray at the coast. She is also concerned about stigma at the beach and experiencing racist or Islamophobic remarks, particularly around praying in pubic.

"If the worst comes to the worst and I'm out, I'll have to pray in my car or in a car park. The weather can be unpredictable, so you don't want the prayer mat to blow away in the wind [and] I don't know if the space is clean."

When she was younger she went on day trips to the coast organised by Islamic groups and enjoyed the community feel. When she thinks of organising a trip herself though, she is unsure that she has the knowledge or experience to know which parts of the coast to visit. She would like to have information on the characteristics of different beaches, particularly whether they are scenic and how busy they tend to be, as well as whether dogs are allowed and what amenities and facilities are available.

Although she used to visit the coast once a year or so as a child, Yasmin feels that her personal circumstances have changed and made it more difficult to visit as often. This included childcare responsibilities as well as health issues which mean she has less energy to go out.

"When I was younger it was once per year, but then university takes over and life gets in the way. […] Then I moved down south to get married and had no access to blue or even green space, […] then I had a child and was trying to survive; work and looking after my daughter was the priority."

Contact

There is a problem

Thanks for your feedback