Covid recovery: learning from person-centred approaches

This report draws on four case studies of person-centred approaches to public service delivery, along with wider evidence, and summarises learning from person-centred approaches

1. How can we better define Person-centred approaches?

The term 'person-centred approaches' was first coined by Carl Rogers in the 1960s. It initially referred to a therapeutic, highly individualised, and non-directive style of counselling.[11] However, over time the term has evolved and moved away from its original, more narrowly defined meaning.

From the case studies, policy documentation and broader literature, it is possible to distil a number of 'core' attributes that characterise current use of the term person-centred approaches within Scotland. These are set out in the table below.

| Attributes of Person-Centred Approaches |

Frequency |

|

|---|---|---|

| Always |

Often |

|

| Holistic: Starts from a holistic understanding of the person and their needs, acknowledging the complexity and individuality of people's lives. |

X |

|

| Ethical: Adheres to a set of strong ethical principles such as dignity, respect, the avoidance of stigma, integrity, compassion, empathy and honesty. |

X |

|

| Relational: Places a strong emphasis on building relationships and trust. Recognises that this can take time and acknowledges the value of strong interpersonal skills within the workforce. |

X |

|

| Strengths/ assets based: Identifies and supports the strengths of the person and their informal networks laying the foundations for co-production and community based working. |

X |

|

| Intensive: Recognises that at times intensive, targeted and co-ordinated support may be required to support people with multiple needs. |

X |

|

| On-going: Accepts that support may require ongoing involvement rather than a one-off intervention. |

X |

|

| Preventative: Understands the importance of early intervention in relation to preventing a situation from deteriorating and new issues from arising. |

X |

|

| Bespoke: Is flexible to the requirements of the person, providing support at times and locations which best meet the person's preferences. |

X |

|

| Local: Understands the value of having a strong presence in communities in order to build familiarity and trust and build on local strengths. |

X |

|

| Provides choice: Recognises the importance of choice, including the person choosing their priorities, the level of service provision, from whom support is received and when to end contact with service providers. |

X |

|

| Addresses power imbalances: Acknowledges implicit power imbalances in the relationships between services and people and seeks to share power through co-production and the promotion of choice. |

X |

|

| Takes risks: May involve taking risks in order to achieve positive outcomes. Person-centred approaches may 'feel' risky as they do not always fit with traditional accountability frameworks. |

X |

|

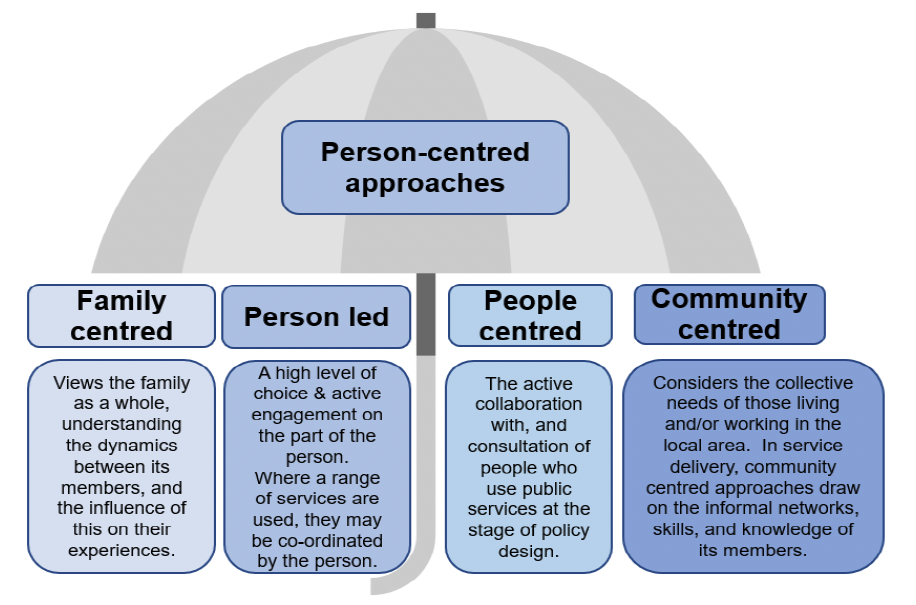

The term 'person-centred' is often used as an umbrella term to describe a range of approaches that share similar attributes to those outlined in the table above. Other related terms that are often used interchangeably with the term can be seen below in Figure 1 and include:

The UN[12], WHO[13] and OECD[14] for example use 'People centred'. Person-centred approaches are also closely related to policy concepts such as "nothing done to me without me," "no wrong door" and "no-one left behind." The key attributes of person-centred approaches are closely aligned with the four pillars of Christie Commission report and the objectives of public service reform.[15]

Contrasting Person-centred Services with 'Task' or 'Service' Centred Approaches

It is useful to contrast person-centred approaches with other more traditional styles of service provision. In task centred approaches, involvement from a service focusses on a single or limited range of issues and the interaction ends once this is addressed through providing information, or the resolution of straightforward problems. The focus is on the task, rather than the person; the solution is more important than the relationship.

Similarly, person-centred approaches can be contrasted with service centred or service centric involvement.[16] Service centred practice is identified as a way of working which prioritises the needs of the service provider. Service centred approaches may fail to fully understand the needs of the person and often set the professional in a position of power, casting people into roles such as "service user", "client" or "patient" [16] [17] [18] [19] [7].

Is Person-centred always the right approach to take?

Taking an intensive / holistic person-centred approach may not always be the 'optimum' approach, especially when service responses are required quickly, when resources are highly constrained or when a simple and standardised intervention is required. While the case studies highlighted in this paper relate to highly complex situations which benefitted from holistic person-centred approaches, in some instances less person-centred approaches may be more appropriate. This may be particularly true in circumstances relating to:

- Standardised Interventions – for example, where interventions relate to a single issue, are low risk, or are focused on straightforward procedure.

- Crisis interventions – when urgency requires professionals to make decisions not in partnership with the person, or where the person cannot manage using their own strengths.

However, even in these instances where a less person-centred approach is taken we should expect to see some elements of the 'core' attributes of a person-centred approach such as dignity, respect and the avoidance of stigma.

Furthermore, services, no matter how transactional, should always be designed around people's needs, rather than being driven by what the system / organisation thinks it should offer as this can often lead to the wrong solution, costly repeat visits, poor experiences for staff, service users and those around them.

Contact

Email: socialresearch@gov.scot

There is a problem

Thanks for your feedback