Health - redesign of urgent care: evaluation - main report

The Redesign of Urgent Care pathway aims to improve patients’ access to urgent care. The evaluation captured patient and staff experiences of the pathway and analysed key urgent care delivery metrics, enhancing our understanding of what is working well and areas for improvement.

3. Methodology

The findings set out in this report were derived from four key data collection and analysis processes, namely:

- A survey of people who had tried to access the RUC pathway by calling NHS 24 111, but ended the call before speaking to anyone (Discontinued Caller survey)

- A survey of patients who had accessed the RUC pathway via NHS 24 111 (Patient survey)

- Online focus groups with NHS staff working across the urgent care pathway

- Interrupted Time Series Analysis incorporating available Urgent Care delivery metrics

A high level overview of the methodologies used to deliver each of these stages is set out below. A comprehensive outline of each is provided in the Technical report.

A Research Advisory Group (RAG) was arranged by the Scottish Government to support the evaluation. The role of the RAG was to provide advice and quality assurance on matters such as the methodology and the final outputs. Membership in the RAG included stakeholders, academics and representatives from other Government departments (See Appendix 1).

3.1 Discontinued Caller survey

To gather the views of people who tried to access the RUC pathway by calling NHS 24 111, but who ended the call before speaking to anyone, an online survey was conducted via the panel provider Norstat, between 29th February and 20th March 2024.

Following a sample screening process 418 people were identified as eligible and consented to participate in the survey. A total of 387 responses were obtained. Analysis of response data, including by subgroups, was undertaken. Subsequent results tables, and an explanation of how to interpret them are outlined in the Technical Report, Sections 5 and 6.

Of these 387 responses, 49% called NHS 24 111 for themselves, 28% on behalf of another adult and 23% on behalf of a child aged 2-16 years (See Technical Report, Section 5, Table 2). It was identified upon examination of the self-reported data that for adults who called on behalf of a child, only 17% provided the correct demographic information for age and education level (i.e. for the child who the call to NHS 24 111 was on behalf of). Due to the poor quality self-reported demographic data, the demographics for the sample overall have not been provided.

3.2 Patient survey

The final Patient survey questionnaire included 48 questions, which focused on people’s experiences of calling NHS 24 111 and any other urgent care services they accessed before or after their call.

Following an approved application to the NHS Health and Social Care Public Benefit and Privacy Panel (PBPP), NHS 24 compiled a sample of eligible patients that had contacted NHS 24 111 between 7th to 21st April 2024 and had selected the RUC pathway via the NHS 24 IVR options (i.e. option people select if they thought they needed to go to A&E). Due to the lower volume of calls from people living in the Island Boards, a slightly longer sampling period was taken for this cohort (25th March to 21st April 2024). The sample was stratified by Health Board (with a minimum sample size set per Board), then a systematic sample was taken from an age-gender sorted list to ensure representativeness by age and gender. Before the survey was launched (and before each reminder mailing), NHS Central Register (NHSCR) carried out checks for any deceased patients so that they could be removed from the sample.

The questionnaire was mailed to a sample of 3,497 individuals. The survey was in field between 22nd May and 12th July 2024, during which time recipients were able to take part via the paper survey mailed to them, online or over the phone. Up to two reminders were mailed to non-respondents to maximise response rates. Overall, 662 of 3215 eligible people[9] responded to the survey, representing a response rate of 21%.

For the 662 people who needed care, 65% of the calls to NHS 24 111 were made by an individual for themselves, 16% on behalf of a child and 20% on behalf of another adult. The demographic characteristics for the 662 people who needed care are included in Tables 3.1 to 3.5 below. The tables show collapsed groupings for the following demographic characteristics: age, gender, ethnicity, urban/rural classification and Scottish Index of Multiple Deprivation (SIMD)[10]. These were primarily derived based on objective data provided by NHS 24 (i.e. year of birth, gender and postcode). The only exception was ethnicity which was self-reported by respondents. Please note that as ethnicity was self-reported, it is possible that an adult who called on behalf of a child provided their own ethnicity rather than the child who they were calling on behalf of. As there were small numbers for some response categories under ethnic group, two categories were created “White ethnic groups” and “Minority Ethnic Groups”[11]. Similarly, the 2-fold classification was used for geographical location to indicate “urban areas” and “rural areas” rather than the 6-fold or 8-fold classifications[12]. The 6- and 8- fold categories were produced however, as low numbers in some categories led to suppression being required the 2-fold classification was deemed most appropriate for reporting. Please note that the total for ethnicity, urban/rural classification and SIMD does not equate to 662. As ethnicity was self-reported, some respondents did not answer this question. For the urban/rural classifications and SIMD, which were derived from postcode, there were some instances were postcodes could not be mapped.

| Age Group | Number | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Under 16 years | 106 | 16% |

| 16-35 | 117 | 18% |

| 36-50 | 92 | 14% |

| 51-65 | 135 | 20% |

| 66-80 | 153 | 23% |

| 81+ | 59 | 9% |

| Gender | Number | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Male | 286 | 43% |

| Female | 376 | 57% |

| Ethnicity | Number | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| White ethnic groups | 588 | 92% |

| Minority ethnic groups | 52 | 8% |

| Urban/Rural Classification | Number | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Urban Areas | 545 | 82% |

| Rural Areas | 116 | 18% |

| Scottish Index of Multiple Deprivation Quintiles | Number | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| SIMD 1 (most deprived) | 98 | 15% |

| SIMD 2 | 113 | 17% |

| SIMD 3 | 135 | 20% |

| SIMD 4 | 155 | 24% |

| SIMD 5 (less deprived) | 158 | 24% |

At the outset of analysis, the response data was cleaned, and derived variables were created to allow for subgroup analysis (e.g., day/time of call).

Selection weighting was applied to the achieved sample to correct for unequal selection probabilities across Health Boards, so that the achieved sample[13] proportions for each Health Board aligned with the full sample proportions. To balance for nonresponse bias, a nonresponse weight was developed (using age and gender) and applied to the achieved sample. Unless otherwise stated, the counts presented in Section 5 of this report are weighted counts.

Frequency table data was generated for each survey question showing weighted counts and percentages for each response option, with the exception of the number of services contacted in addition to NHS 24 111 and caller type (Technical Report, Section 8). A breakdown of the frequency data by a number of subgroups was produced (e.g., day/time of call). Significance testing was performed to assess whether differences between the groups were statistically significant.

Where the unweighted base size per question, or within any sub-group breakdown, is less than 11, the data are suppressed and replaced with an asterisk (*).

3.3 Focus Groups with NHS staff

Three focus groups were conducted during March and April 2024 with staff working across the urgent care pathway:

- Focus Group 1: staff from NHS 24 and Flow Navigation Centres

- Focus Group 2: staff in managerial roles working across the urgent care pathway

- Focus Group 3: clinical staff working in primary and secondary urgent care settings

Focus groups took place online using video conferencing software (Microsoft Teams) and was facilitated by an experienced qualitative researcher. Participants were given a £40 shopping voucher as a recognition and thanks for their time[14].

A purposive sampling approach was used to recruit staff for the focus group. Picker contacted each Board for their support in disseminating information about the focus groups with staff, including via an information sheet and a social media advert. Any staff working in urgent and unscheduled care that were interested in taking part were asked to contact Picker directly. They were then sent an online form to understand their role, sector of the urgent care pathway, Health Board(s) and demographic information. This form was used to screen respondents for eligibility to participate in a discussion. Further information on the screening and selection process can be found in the Technical Report, Section 3.4.

A thematic analysis was undertaken to analyse the data from the focus groups. This process involved:

- Collation of notes

- Automatically generated Teams transcriptions and audio file transcriptions

- Using NVivo to iteratively identify and categorise themes (or codes) within the responses

- Identifying key concepts and patterns in the data which formed the basis for thematic reporting (with quotes used to exemplify).

3.4 Analysis of existing data: Interrupted Time Series Analysis

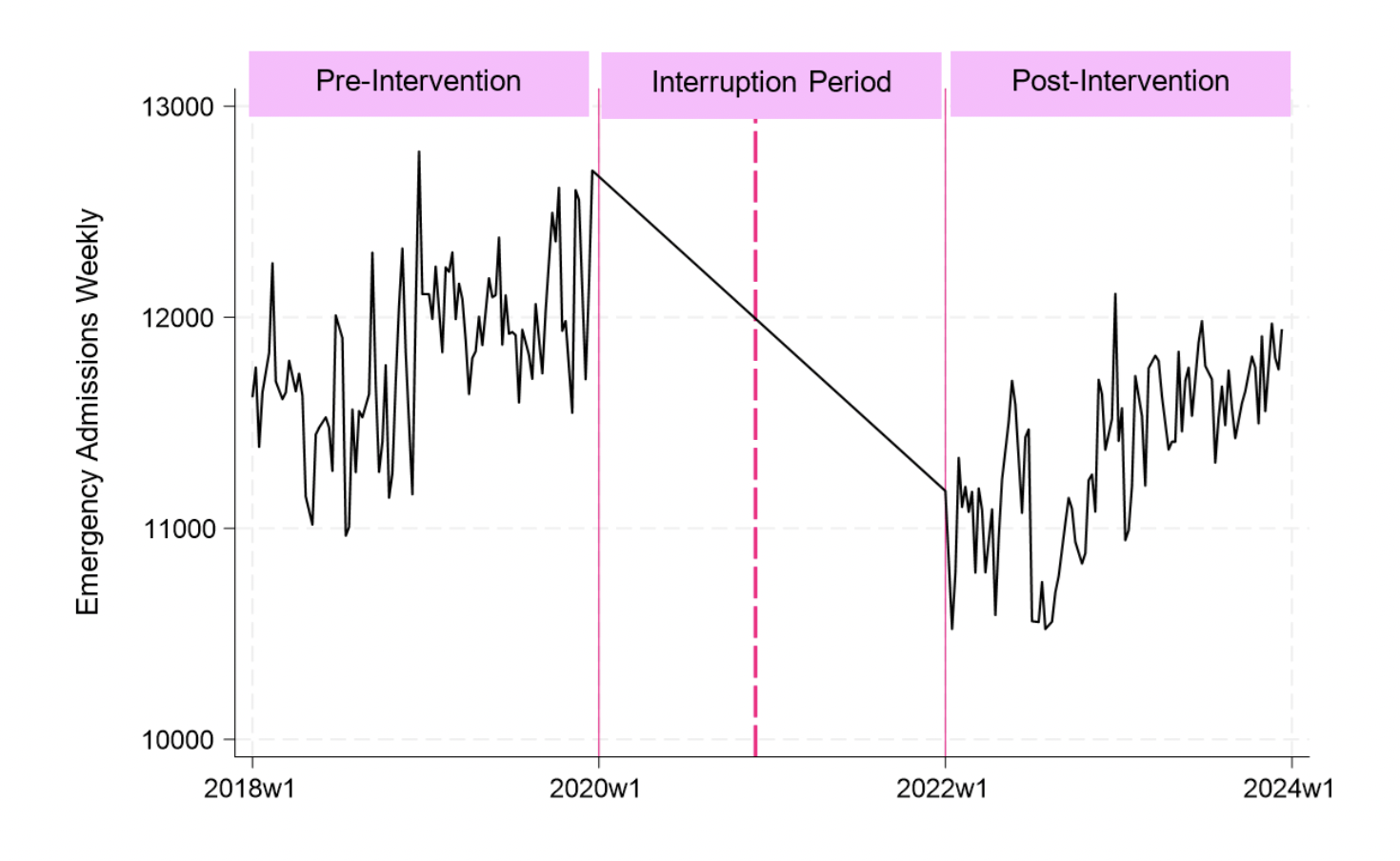

To support the overall evaluation, Interrupted Time Series Analysis was undertaken to assess changes to key Urgent Care delivery metrics, comparing pre and post implementation of the RUC pathway. Specifically the analytical approach at national level compared data from a 2 year period post RUC implementation (January 2022 to December 2023) with a projected position based on trends during 2018 to 2019 (pre RUC implementation). This offers a comparison between actual state of play during January 2022 to mid-December 2023 with a counterfactual state of play at the same time point, based on a scenario where there is continuation of baselines trends from 2018 and 2019. At a Health Board level, the delivery metrics for each Board were compared with one or more ‘control’ Board(s), which were identified for each delivery metric based on similar trends during the pre-implementation period (2018 to 2019). Changes pre to post RUC implementation for each Board are therefore presented as the change relative to their ‘control’ Board(s), which could differ for each delivery metric. A comprehensive outline of the methodology is provided in the Technical Report, Section 3.5.

It should be noted that causation of any change between the comparators cannot be conclusively determined, and is likely to have been driven by several factors, including but not limited to the introduction of RUC. Such factors will notably include impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic, some of which is not yet quantifiable.

3.4.1 One-to-one interviews to inform identification of delivery metrics

One-to-one interviews with representatives from NHS Scotland and the Centre for Sustainable Delivery were undertaken to understand the context for identification of delivery metrics. The decisions context consisted of four key elements[15]:

- What was the RUC, and how should it look in the future?

- Who was/is involved in the development of the RUC?

- How does the decision to fund the RUC interact with other funding decisions?

- What are the anticipated delivery metrics affected by the RUC?

3.4.2 Identifying outcomes

Urgent Care delivery metrics were selected on the basis of assessment of the one-to-one interviews, published literature[16], and the availability of data. All selected outcomes were included as dependent variables in the Interrupted Time Series Analysis.

3.4.3 Interrupted Time Series Analysis

Interrupted Time Series Analysis was identified as the most appropriate method of analysis for the RUC because it compares trends during two non-sequential periods (pre- and post-intervention) and it may include a control group or not. In this analysis, trends in delivery metrics in a two year period prior to RUC implementation (i.e. from 01 January 2018 to 01 January 2020, pre period) were compared with the trends in delivery metrics between 01 January 2022 and 11 December 2023 (i.e. post period). It was decided to exclude the two-years worth of data between 01 January 2020 and 01 January 2022 in order to a) avoid disruption in service use caused by the COVID-19 pandemic that would introduce bias in the results, and b) to account for the gradual implementation of RUC across the nation. However, it is important to note that this analysis assesses variations between these two periods. Causation of any variation between these comparators cannot be conclusively determined, and is likely to have been driven by several factors, including but not limited to the introduction of RUC. Such factors will notably include impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic, some of which is not yet quantifiable.

Figure 3.1 illustrates the interruption period for the delivery metric ‘emergency admissions weekly’. The vertical solid pink lines represent the beginning and end of the interruption period. The vertical dashed pink line represents the implementation of the RUC.

Routinely (weekly) collected data was accessed through Public Health Scotland (PHS) to assess changes pre and post RUC implementation in terms of each delivery metric, at national and Health Board level. Analysis was conducted firstly at national level followed by an analysis at Health Board level. The national-level analysis did not include a control country, as only data for Scotland was available. Thus, the interrupted time series analysis performed at national level estimated the difference in the trends in the delivery metrics between the trends in the pre and post RUC implementation periods.

However, in the interrupted time series analysis at Health Board level, it was possible to assess the “performance” of each Health Board by comparing it to one or more Health Boards with similar pre-trends (i.e. control). Performance in this context therefore refers to variations in the delivery metrics relative to one or more Health Boards which exemplified similar (i.e. non-significantly different) trends for that delivery metric during the pre-implementation period (01 January 2018 to 01 January 2020). Again though, causation behind a relative divergence of a delivery metric within a Health Board away from another or others with similar trends during the pre-period cannot be conclusively determined, and may have been driven by several factors, including but not limited to the introduction of RUC.

The selection of control Health Board(s) was done for each Health Board and delivery metric (i.e. a Health Board could have different control Health Board(s) between two different delivery metrics). Choosing control Health Boards based on their similar starting point and pre-trends in a delivery metric seeks to somewhat overcome the limitations of having data for all potential confounders that may influence these pre-trends (e.g. demographics of the population in the catchment area, size of the Health Board, capacity of the services in a Health Board). So, regardless of the underlying reason, if two Health Boards had similar starting levels and trends for a particular delivery metric (e.g. unscheduled hospital admissions) during the two years prior to RUC implementation, they were regarded as a control to each other for this delivery metric. The identification of a suitable control for each Health Board is described extensively in the Technical Report (see Section 3.5.3).

It must be noted however that for many of the delivery metrics (specifically those based on absolute numbers, e.g. unscheduled hospital admissions) it was not possible to identify a suitable ‘control’ Health Board for NHS Greater Glasgow and Clyde, given the far greater populus serviced by this Board. As such, the Health Board level Interrupted-Time Series Analysis does not provide findings for NHS Greater Glasgow and Clyde for these delivery metrics (see Technical report, Section 9 Tables 1 to 5).

To support interpretation of changes in delivery metrics at national level, the results of the analysis were used to estimate annualised outcomes (i.e. volume of each delivery metric in a “standardised” year) in the pre and post periods. The concept of “standardised” year in the pre and post periods was used in order to facilitate interpretation of the results as it could be interpreted as a typical year of trends immediately before and after RUC implementation. In the analysis, a “standardised” year uses the estimates of the two years in the pre-period and the two years in the post-period. Standardised years were calculated by adding the start value of the delivery metric in a given time period (either pre- or post- period), to the trend of the given time period (either pre- or post- time trend) multiplied by 52 (representing the 52 weeks in a year period). This allows for comparison of the RUC on all selected delivery metrics based on changes in trends during the pre- and post- implementation periods.

3.5 Limitations of the evaluation

There were some limitations to the evaluation, which are structured around the main approaches and sources of data used.

3.5.1 Surveys

Both the Patient survey and Discontinued Caller survey focused on a cohort of people that contacted, or tried to contact, NHS 24 111 to access urgent care by selecting the A&E pathway. This group may differ in socioeconomic characteristics and/or in health need to those who access urgent care services, such as A&E services, directly. For a more complete evaluation of the RUC programme, insight from patients who access urgent care, other than via NHS 24 111, would be beneficial.

The response rate to the Patient survey (which included an online completion option) was lower than expected (21% rather than 30%), so the maximum margin of error[17] is slightly larger than anticipated (+/-4% rather than +/-3%) meaning the reliability of the estimates are lower than expected. There were some significant differences in response rates by demographic groups (age and SIMD) and some groups are likely to be underrepresented in the findings.

The lower than expected number of responses may partly be due to the large number of surveys that were undelivered due to poor quality patient home address information (i.e. n=271; 8% of the total sample were undelivered). In 65% of these cases, the reason logged for the mail being undelivered was due to the address being incomplete or unknown, with 34% due to the recipient having moved from the address. The proportion of undelivered questionnaires ranged between 2% and 12% across Health Boards. Future surveys should check patient addresses with NHS Central Register to minimise the number of questionnaires returned undelivered.

The questionnaire used in the Patient survey was designed before NHS 24 introduced their virtual queue in December 2023, so the content does not take into account this new service. The service was introduced at the busier times for the service to provide callers with an option for their call to be placed in a ‘virtual queue’. The recorded NHS 24 endpoint in the survey sample showed 40% had an FNC endpoint where they would receive a call back from a health professional. However, at Q14 in the survey (i.e. ‘After your call to NHS 24 111, did a healthcare professional call you back to discuss your health concern?’), 59% said they received a call back. This inconsistency may reflect that some respondents may have reported they received a ‘call back’ when it was the virtual queue contact from NHS 24.

The Discontinued Caller survey was limited to those who were registered to the panel who may be more engaged in research and/or driven by any incentives received for completing the survey. Participants needed to have online access and be technologically able so this will exclude some people. Responses from the Island Boards were low, so the experiences of those who discontinued a call to NHS 24 111 and living in the Island Boards are not represented in these findings (see Technical Report, Section 5, Table 3). However, the views and experiences of people living in more rural geographical areas of Scotland were captured as there were respondents from NHS Highland, NHS Borders, NHS Dumfries and Galloway and NHS Ayrshire and Arran.

The target number of responses from the Discontinued Caller survey was 350 to achieve a maximum margin of error of +/-5% at the 95% confidence level. Whilst this target was achieved with 387 responses, the number of respondents in some of the subgroup analyses were small. It also appeared that many of the respondents who called NHS 24 111 to get help for a child incorrectly completed the demographic questions about themselves rather than the child requiring help, despite the survey wording asking for them to answer on behalf of the person they were calling for. This risk could be mitigated in the future by investing time and resource to cognitively test the questions with patients to check understanding and amend the wording/structure of the questions to ensure improved completion.

3.5.2 Focus groups

Some care should be taken when interpreting the findings from the focus groups with staff as not all NHS Boards were represented. Also, there was mostly just one person per board and so the nature of their role may impact on their level of knowledge or insight into the implementation of the RUC pathway within their board.

3.5.3 Analysis of existing data

The analysis of existing data at national level compared data from a 2 year period post RUC implementation (January 2022 to mid December 2023) with a projected position based on trends during 2018 to 2019 (pre RUC implementation). For each delivery metric, this offers a comparison between actual state of play during the 2 year period post RUC implementation with a counterfactual state of play at the same time point, based on a scenario where there is continuation of baselines trends from 2018 and 2019. The year 2019 was an exceptionally busy year for urgent care services and therefore, the pre-trends in the interrupted time series analysis may be biasing the results. The analysis at a Health Board level compared delivery metrics for each Board with one or more ‘control’ Board(s), which were identified for each delivery metric based on similar trends during the pre-implementation period (2018 to 2019). Changes for each Board are therefore presented as relative to their ‘control’ Board(s), which could differ for each delivery metric. Despite the advanced methodological approach, this analytical technique has several limitations and its results should be interpreted with caution.

The first major limitation is related to the observational nature of this analysis. Despite the employment of Interrupted Time Series Analysis and thorough methodological approach, the results may still be subjected to bias. It is important to note that causation of any change between these comparators at national and Health Board level cannot be conclusively determined, and is likely to have been driven by several factors, including but not limited to the introduction of RUC. Such factors will notably include impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic, some of which is not yet quantifiable.

Another limitation is related to the data available for these analyses. There were several gaps in the data regarding:

- Flow navigation centre, hospital-at-home or virtual activity

- Planned/scheduled A&E attendances are not consistently coded by NHS Boards meaning scheduled attendances (following a referral from an FNC) may be coded as ‘unplanned’ or not at all. An updated approach to coding urgent care attendances will be introduced in February 2025[18] which will include a new ‘planned’ attendance code. An assessment of the impact of this change estimates a c.4% increase nationally in the total number of attendances, although the impact will vary across different Health Boards (Annex 1 - Percentage of attendances coded as 'new planned' by health board).

- Health Board level infrastructure (over time)

- Other relevant criteria such as mortality or quality of life

- The cost of the RUC.

In addition, coding issues in the data mean that in many boards, notable proportions of scheduled A&E attendances coming through the FNC pathway were being submitted as unplanned A&E attendances through 2021 to 2023 and therefore, included in performance monitoring and official statistics.

Future evaluations should seek to retrieve data capturing measures of health, including quality of life. Further, to assess the continued viability of RUC, the complete cost of the service should be included in the analysis.

Contact

Email: dlhscbwsiawsiaa@gov.scot

There is a problem

Thanks for your feedback