Managing deer for climate and nature: consultation analysis

Analysis of responses to the Scottish Government consultation on 'managing deer for climate and nature'.

3 Enhancing the natural environment (Q1–Q8)

3.1 Part 1 of the consultation paper addressed the theme of enhancing the natural environment. It set out proposals for (i) addressing perceived deficiencies in existing deer legislation and (ii) modernising deer management in the context of climate change and biodiversity loss.

3.2 The consultation paper explained that current regulatory powers for deer management are at present limited and focus on damage intervention (i.e. where there is damage being caused and/or a risk of damage). New powers for NatureScot were proposed – in the form of Deer Management Nature Restoration Orders (DMNROs). These would widen the scope for regulatory intervention based on NatureScot’s assessment of whether significant gains could be made in meeting biodiversity and climate objectives through deer management actions. The proposals addressed the process for selecting areas for a DMNRO, the period during which a DMNRO would apply, financial support and advice, and penalties for non-compliance.

3.3 Eight questions invited views on the introduction of DMNROs.

Question 1: Do you agree that NatureScot should be able to intervene, through DMNROs, to ensure that action is taken to manage deer, where deer management has been identified as a key part of nature restoration? [Yes | No | Don’t know]

Question 2: Do you agree with our proposed criteria for a DMNRO? [Yes | No | Don’t know | I don’t agree with DMNROs]

Question 3: If you answered no to the previous question, what criteria, if any, would you recommend? [There should be no criteria/restrictions | There should be more criteria/restrictions | I don’t agree with DMNROs | Don’t know]

Question 3a: Please provide reasons for your answer here.

Question 4: Do you agree that NatureScot should be able to require a person who is subject of a DMNRO to undertake a range of actions to achieve deer management objectives in these circumstances? [Yes | No | Don’t know]

*Question 5: Do you agree that if financial incentives for deer management are created, individuals subject to DMNROs should be automatically eligible for such support? [Yes | No | Don’t know]

Question 6: Do you agree that non-compliance with DMNROs should be treated in the same way as non-compliance with existing control schemes? [Yes | No | Don’t know]

Question 7: Do you agree that NatureScot should be able to recover costs from the landowner where they are required to intervene as a result of non-compliance with DMNROs? [Yes | No | Don’t know]

Question 7a: If you do not support cost recovery, what alternative non-compliance measures, if any, would you recommend?

Question 8: Please provide any further comments on the questions in this section here.

* Note that this question was not included in the online consultation response form.

DMNROs (Q1)

3.4 Question 1 asked respondents if they agreed that NatureScot should be able to intervene, through DMNROs, to ensure that action is taken to manage deer, where deer management has been identified as a key part of nature restoration.

3.5 Table 3.1 shows that, overall, 64% of respondents agreed and 34% disagreed. The remaining 1% of respondents said ‘don’t know’. Individuals were more likely than organisations to agree with the proposal (65% versus 51%).

3.6 Conservation and animal welfare organisations almost universally agreed with the proposal (97%). Around three-quarters of organisations in the ‘other organisation type’ category (77%) also agreed. By contrast, 78% of land management, deer and sporting organisations disagreed.

| Respondent type | Yes | No | Don't know | Total | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | |

| Land management, deer and sporting organisations | 7 | 14% | 39 | 78% | 4 | 8% | 50 | 100% |

| Conservation and animal welfare organisations | 32 | 97% | 1 | 3% | 0 | 0% | 33 | 100% |

| Other organisation types | 10 | 77% | 2 | 15% | 1 | 8% | 13 | 100% |

| Total organisations | 49 | 51% | 42 | 44% | 5 | 5% | 96 | 100% |

| Total individuals | 971 | 65% | 498 | 34% | 17 | 1% | 1,486 | 100% |

| Total, all respondents | 1,020 | 64% | 540 | 34% | 22 | 1% | 1,582 | 100% |

Percentages may not total 100% due to rounding.

A more detailed breakdown of responses by organisation type is shown in Annex 3, Table A3.1.

DMNRO criteria (Q2 and Q3)

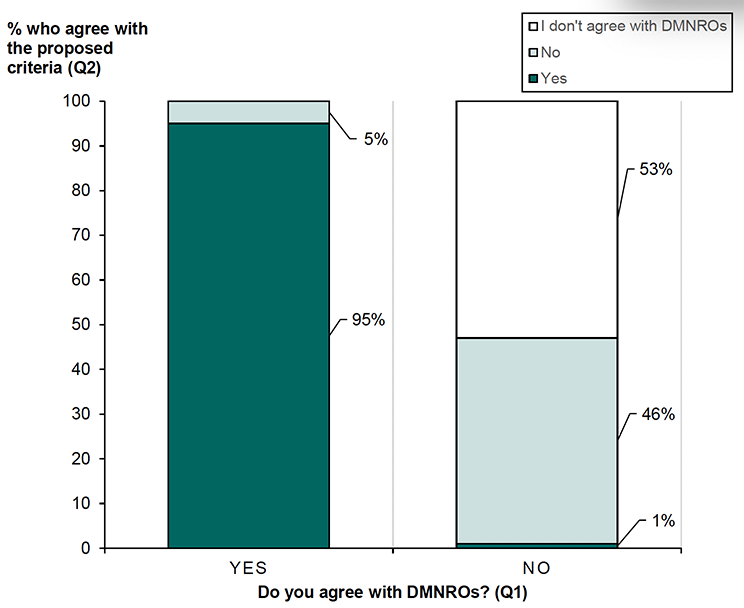

3.7 Question 2 asked respondents whether they agreed with the proposed criteria for the establishment of a DMNRO. These were that (i) they can only be ordered where there are social, economic or environmental benefits to be achieved through nature restoration, and (ii) additional deer management is a key factor, or one of the key factors, in securing that benefit. Respondents’ answers at Question 2 were strongly related to their answers at Question 1. The vast majority of those who agreed with the use of DMNROs also agreed with the proposed criteria for DMNROs. Most respondents who did not agree with DMNROs simply repeated this view at Question 2 or said they did not agree with the proposed criteria. This is illustrated in Figure 3.1 below.

Note: The percentages shown are based on 1,020 respondents who answered ‘yes’ at Question 1 and 538 who answered ‘no’ at Question 1. Respondents who answered ‘don’t know’ at either Question 1 or Question 2 (35 in total) are not included. See Table 3.2 below for details of these responses.

3.8 Table 3.2 shows the association between the responses at Questions 1 and 2 in table format, with the responses for organisations and individuals presented separately.

3.9 The table shows that, for organisations:

- 92% (45 out of 49) of those who agreed with the use of DMNROs (i.e. they answered ‘yes’ at Question 1) went on to say they agreed with the proposed criteria for DMNROs (i.e. answering ‘yes’ at Question 2). Just 4% of those (2 out of 49) who agreed with DMNROs said they did not agree with the proposed criteria, and 4% (2 out of 49) said they did not know.

- 97% (41 out of 42) of those who did not agree with the use of DMNROs at Question 1 went on to say at Question 2 either that they did not agree with the proposed criteria (57%), or they did not agree with DMNROs (40%). One final organisational respondent said they did not agree with DMNROs but did agree with the proposed criteria.

3.10 For individuals:

- 94% (910 out of 971) of those who agreed with the use of DMNROs at Question 1 went on to say at Question 2 that they agreed with the proposed criteria. Just 5% (48 out of 971) of those who agreed with DMNROs said they did not agree with the proposed criteria, and 1% (8 out of 971) said they did not know. Note also that 1% of individuals (5 out of 971) who agreed with the use of DMNROs at Question 1 said that they did not agree with DMNROs at Question 2.

- 98% (487 out of 496) of those who did not agree with the use of DMNROs at Question 1 went on to say at Question 2 either that they did not agree with the proposed criteria (44%) or they did not agree with DMNROs (54%). In addition, 1% (6 out of 496) who said at Question 1 that they did not agree with DMNROs went on to say at Question 2 that they did agree with the proposed criteria. Another 1% (3 out of 496) said they did not know.

| Q1: Do you agree with DMNROs? | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Q2: Do you agree with the proposed criteria? | Yes (Q1) | No (Q1) | Don’t know (Q1) | |||

| Organisations | n | % | n | % | n | % |

| Yes (Q2) | 45 | 92% | 1 | 2% | 1 | 20% |

| No (Q2) | 2 | 4% | 24 | 57% | 1 | 20% |

| Don't agree with DMNROs (Q2) | 0 | 0% | 17 | 40% | 0 | 0% |

| Don’t know (Q2) | 2 | 4% | 0 | 0% | 3 | 60% |

| Total, organisations | 49 | 100% | 42 | 100% | 5 | 100% |

| Individuals | n | % | n | % | n | % |

| Yes (Q2) | 910 | 94% | 6 | 1% | 5 | 29% |

| No (Q2) | 48 | 5% | 220 | 44% | 3 | 18% |

| Don't agree with DMNROs (Q2) | 5 | 1% | 267 | 54% | 4 | 24% |

| Don’t know (Q2) | 8 | 1% | 3 | 1% | 5 | 29% |

| Total, individuals | 971 | 100% | 496 | 100% | 17 | 100% |

Percentages may not total 100% due to rounding.

Findings from Question 2 broken down by organisation type are shown in Annex 3, Table A3.2.

Alternative criteria for DMNROs (Q3)

3.11 Question 3 was directed at respondents who did not agree with the proposed criteria for DMNROs at Question 2 (set out above). It asked them to choose from a range of options to explain why they did not agree with the proposed criteria.

3.12 Table 3.2 above shows that a small number of respondents – 50 in total (2 organisations and 48 individuals) – agreed with DMNROs but did not agree with the proposed criteria. Of these 50:

- 20 wanted to see more criteria/restrictions attached to the use of DMNROs

- 25 wanted no criteria/restrictions.

- 2 said they did not know.

- 3 did not answer the question.

3.13 Full results for Question 3 are shown at Annex 3 (see Tables A3.3 to A3.5.) Note, however, that respondents often made similar points in their comments (see paragraphs 3.23 to 3.32) regardless of how they answered the closed part of Question 3. This suggests there may have been some confusion about how to answer Question 3, and that the figures in paragraph 3.12 above should therefore be treated with caution.

3.14 Respondents who answered Question 3 were asked to give the reasons for their views. However, those who responded to this question (436 respondents – 52 organisations and 384 individuals) included respondents who had not answered the closed part of Question 3, and the comments made covered a range of issues relating to respondents’ views of DMNROs and the proposed criteria for DMNROs. Thus, not all of the comments made at Question 3 were directly related to that question.

3.15 The discussion below provides a summary of the main themes from all the comments made at Question 3. However, it should be noted that around three-quarters of those who commented at Question 3 were respondents who said (at Question 1) that they did not support DMNROs. This means that the views expressed at Question 3 were largely dominated by those who opposed DMNROs.

3.16 The sections below discuss (i) views in favour of DMNROs, (ii) views opposed to DMNROs, (iii) views on the criteria for DMNROs, and (iv) suggestions for alternative/ additional criteria. Respondents also raised a range of questions about the practical implementation of DMNROs. These comments are discussed at the end of this chapter together with similar comments made at Questions 7 and 8.

Views in favour or DMNROs

3.17 As Table 3.1 showed, those in favour of DMNROs comprised nearly all the conservation and animal welfare organisations, three-quarters of organisations in the ‘other organisation type’ category, and around two-thirds of individuals.

3.18 These respondents often said that deer overpopulation was the main obstacle to ecosystem recovery in certain areas of Scotland. They highlighted the benefits of improved deer management, including the regeneration of natural woodlands, reduced flooding, and greater carbon sequestration. In addition, this group pointed to the problems of deer causing damage to small farms and gardens in some parts of Scotland, the growing incidence of Lyme Disease, and the large numbers of road accidents involving collisions with deer. Some also suggested that better management of wild deer populations would have benefits in terms of animal welfare – particularly in areas where deer mortality is high due to insufficient food in the winter months. A recurring view among this group was that deer numbers need to be controlled as a matter of urgency.

3.19 Some respondents who supported DMNROs acknowledged that deer management groups have had success in reducing deer populations in parts of Scotland, but thought that, overall, deer numbers were still far too high. These respondents emphasised the need for ‘radical and new’ approaches. They supported a ‘landscape scale’ approach to sustainable deer management that was capable of achieving a long-term reduction in deer numbers without having to cull repeatedly. They also thought it was important that such efforts are not impeded by deer moving across land ownership boundaries, and there was a suggestion that the whole of Scotland should be the subject of a DMNRO, with locations being excluded only if there was a good justification for doing so. These respondents wanted the use of DMNROs to be linked to natural regeneration and improvements in ecological connectively, and to aim for full recovery and restoration of natural processes.

3.20 Some in this group suggested that NatureScot has had (for many years) the necessary powers to achieve more sustainable deer populations in Scotland but has not used them. These respondents wanted to know that action will be taken under any new legislation and that NatureScot will have the capacity, resources and legal support to do so.

Views opposed to DMNROs

3.21 Among those who opposed DMNROs, four main reasons were given:

- There is no requirement for DMNROs: Respondents who expressed this view suggested that most deer managers have been supportive of the Scottish Government’s aim of reducing deer numbers over the past decade, and existing legislation already allows action to be taken where management practices are poor. They noted that existing legislative measures for managing deer have been seldom used, arguing that this demonstrated that there is no need for additional measures. In their view, introducing DMNROs would merely add another layer of ‘bureaucracy’ and alienate those who are managing their local deer population well. These respondents thought it would be preferable to revise the existing provisions in the Deer (Scotland) Act 1996 to address any perceived limitations of existing powers, rather than introduce new legislative powers. It was also suggested that better use could be made of existing legislation by including an intermediate step or agreement, where Section 7 Agreements progress to Section 8 Control Orders and Land Management Agreements. Occasionally, respondents in this group agreed that the current legislation required modernisation. However, they argued that any significant proposed changes should be based on evidence and provide an indication of the likely impacts and costs of intervention. In their view, no evidence had been provided to support the proposals.

- Deer are only part of the problem: Respondents thought that a focus solely on deer management, to the exclusion of other issues, would not be effective in achieving nature restoration. These respondents argued that ecological restoration and enhancement is complex and requires an understanding of all the factors that have led ecological change in Scotland over many years. Such factors have included poor drainage, afforestation, and developments by power companies, as well as over-grazing by herbivores more generally – not only deer but sheep, wild goats, rabbits and mountain hares.

- DMNROs would penalise landowners: Some respondents thought the introduction of DMNROs would lead to an increased management burden for landowners. Others noted that landowners can have little control over the number of deer on their property since deer herds move seasonally over large distances. Therefore, landowners should not be penalised when large populations of deer pass through their land.

- There could be legal challenges to DMNROs: Respondents who raised this point suggested that the use of DMNROs would mark a significant departure from the current voluntary approach to deer management. There were concerns that the proposed approach would, essentially, make nature restoration (as defined by the Scottish Government) ‘compulsory’. This, they suggested, was likely to have significant legal and practical consequences and the process of DMNRO designation was therefore likely to be slow and ‘argumentative’. Others saw DMNROs as representing an infringement on property rights. These respondents argued that under the European Convention on Human Rights, Protocol 1, Article 1, landowners are entitled to the peaceful enjoyment of their property.

3.22 In general, respondents who opposed DMNROs thought it would be better to continue to work with landowners and deer managers in a consultative and voluntary way.

Views on the proposed criteria for DMNROs

3.23 As mentioned above, the proposed criteria for DMNROs were that (i) they can only be made where there are social, economic or environmental benefits to be achieved through nature restoration, and (ii) additional deer management is a key factor or one of the key factors in securing that benefit.

3.24 There was little comment on the criteria from those who agreed with them. Occasionally, respondents in this group suggested that (i) deer management should be based on evidence, (ii) there should be mandatory targets for landowners to reduce the numbers of deer on their land, and (iii) there may need to be different criteria for different parts of Scotland since each area has its own ecosystem. There was also some concern from this group that the criteria could be disputed by landowners/lawyers, and therefore that it might be better to have no set criteria, and for DMNRO use to be based on NatureScot’s considered opinion. There was also concern about language/terminology. For example, it was suggested that ‘natural capital enhancement’ is a vague and problematic term as deer are currently treated as capital by landowners. There was also a suggestion that ‘ecosystem restoration’ would be a more appropriate term than ‘nature restoration’ which may have multiple different interpretations.

3.25 Among those who did not support DMNROs (or the criteria proposed for them), there was a repeated view that the proposed criteria were ‘subjective’ and that a lack of clarity about the criteria would make it difficult for land managers to anticipate and respond to them.

3.26 Some respondents in this group questioned every aspect of the proposed criteria – the definition of ‘nature restoration’, how socio-economic impacts would be assessed, and how ‘success’ would be measured. These respondents argued that there would need to be explicit and definitive criteria for imposing DMNROs, rather than a ‘discretionary and subjective’ assessment of possible future benefits by NatureScot.

3.27 Some thought that the perceived subjectiveness of the proposed criteria would lead to legal challenges. By contrast, others were concerned that it could be difficult for a landowner or land manager to appeal against a subjective assessment of the potential benefits of nature restoration that might happen, and the role of deer management in securing this.

Alternative/additional criteria proposed for DMNROs

3.28 Among respondents who said they were in favour of DMNROs (they answered ‘yes’ at Question 1) but not in favour of the proposed criteria (they answered ‘no’ at Question 2), there were several different views on the criteria.

3.29 Some proposed specific criteria to be added – or additional factors that should be taken into account in issuing a DMNRO, including:

- Deer welfare and health

- Economic impacts of deer overpopulation on forestry

- Damage to agricultural crops

- Impacts on crofting communities

- Increased incidence of road accidents.

3.30 Others proposed alternative criteria. Some made specific suggestions, for example, that DMNROs should seek to achieve a particular density of deer per square kilometre. These suggestions ranged from 2 per square kilometre to 20 per square kilometre.[4] Others in this group offered more general suggestions, for example:

- The criteria should not seek to achieve economic benefits, only social and environmental benefits.

- The criteria should not seek to achieve social benefits.

- Environmental benefits should be the only criterion.

3.31 Finally, as noted above, others in favour of DMNROs wanted to make it easier for NatureScot (or NatureScot at the direction of Scottish Ministers) to be able to act quickly to reduce deer numbers. These respondents favoured lowering the threshold for intervention or having no criteria at all for intervention, as they thought the requirement to meet a set of criteria would merely provide loopholes and be used to challenge, delay or prevent the process of reducing deer numbers. Occasionally, respondents in this group made rather different points. For example, there was a view that, while the principle of DMNROs was good, they should always be implemented in consultation with the landowner unless there were exceptional circumstances.

3.32 Respondents opposed to DMNROs also occasionally made suggestions for alternative criteria, including, for example, (i) evidence of damage to the environment caused by deer, and (ii) whether the number of deer exceeds the carrying capacity in a particular ecosystem or area. In relation to the latter approach, it was thought that the impact of other herbivores on carrying capacity would also need to be considered.

Deer management requirement for those subject to a DMNRO (Q4)

3.33 Question 4 asked respondents if they agreed that NatureScot should be able to require a person who is subject to a DMNRO to undertake a range of actions to achieve deer management objectives. Examples of such actions given in the consultation paper included (i) reducing deer numbers by setting targets for density or culling over a period of time, (ii) putting fencing in place to prevent deer damaging restoration projects within a DMNRO area, and (iii) other work to support deer management including habitat assessments, detailed cull plans, and cull reporting.

3.34 Table 3.4 shows that, overall, 65% of respondents agreed that NatureScot should be able to require a person who is subject to a DMNRO to undertake a range of deer management actions and 33% disagreed. The remaining 2% said ‘don’t know’. Individuals were more likely than organisations to agree with the proposal (66% versus 49%).

3.35 Conservation and animal welfare organisations almost universally agreed with the proposal (97%). A majority of respondents in the ‘other organisation types’ category also supported the proposal (62%). By contrast, a large majority of land management, deer and sporting organisations (80%) disagreed.

| Yes | No | Don't know | Total | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Respondent type | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % |

| Land management, deer and sporting organisations | 7 | 14% | 39 | 80% | 3 | 6% | 49 | 100% |

| Conservation and animal welfare organisations | 32 | 97% | 1 | 3% | 0 | 0% | 33 | 100% |

| Other organisation types | 8 | 62% | 1 | 8% | 4 | 31% | 13 | 100% |

| Total organisations | 47 | 49% | 41 | 43% | 7 | 7% | 95 | 100% |

| Total individuals | 974 | 66% | 481 | 32% | 30 | 2% | 1,485 | 100% |

| Total, all respondents | 1,021 | 65% | 522 | 33% | 37 | 2% | 1,580 | 100% |

Percentages may not total 100% due to rounding.

A more detailed breakdown of responses by organisation type is shown in Annex 3, Table A3.6.

Eligibility for financial incentives (Q5)

3.36 Question 5 asked respondents if they agreed that, if financial incentives for deer management are created, individuals subject to DMNROs should be automatically eligible for such support. Only respondents who completed a Word version of the consultation questionnaire had access to this question; the question was not available to online respondents. (See paragraph 1.11.)

3.37 Responses were received from 19 respondents. Of these, 16 said ‘yes’, 2 said ‘no’ and 1 said ‘don’t know’. Of the 16 respondents who said yes, 7 were land management, deer and sporting organisations, 5 were conservation and animal welfare organisations, 1 was an organisation in the food sector, and 3 were individuals. Because of the small number of responses to this question, no table is provided here. However, a full breakdown of the responses, by respondent and organisation type is shown in Annex 3, Table A3.7.

3.38 Note that respondents often discussed the issue of financial incentives in their responses to Question 7 (which concerned cost recovery), and these views are discussed below with other comments made at Question 7.

Non-compliance (Q6)

3.39 Question 6 asked respondents if they agreed that non-compliance with DMNROs should be treated in the same way as non-compliance with existing deer control schemes.

3.40 Table 3.6 shows that, overall, 61% of respondents agreed, 34% disagreed, and 5% said ‘don’t know’. Individuals were more likely than organisations to agree (62% versus 46%). The vast majority of conservation and animal welfare organisations (88%) agreed. In addition, 62% of organisations in the ‘other organisation types’ group also agreed. By contrast, a large majority of land management, deer and sporting organisations (76%) disagreed.

| Yes | No | Don't know | Total | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Respondent type | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % |

| Land management, deer and sporting organisations | 7 | 14% | 37 | 76% | 5 | 10% | 49 | 100% |

| Conservation and animal welfare organisations | 29 | 88% | 0 | 0% | 4 | 12% | 33 | 100% |

| Other organisation types | 8 | 62% | 3 | 23% | 2 | 15% | 13 | 100% |

| Total organisations | 44 | 46% | 40 | 42% | 11 | 12% | 95 | 100% |

| Total individuals | 925 | 62% | 497 | 33% | 62 | 4% | 1,484 | 100% |

| Total, all respondents | 969 | 61% | 537 | 34% | 73 | 5% | 1,579 | 100% |

Percentages may not total 100% due to rounding.

A more detailed breakdown of responses by organisation type is shown in Annex 3, Table A3.8.

Recovery of costs (Q7)

3.41 Question 7 asked respondents if they agreed that NatureScot should be able to recover costs from a landowner where an intervention is required due to non-compliance with DMNROs.

3.42 Table 3.7 shows that, overall, 60% of all respondents agreed and 36% disagreed. The remaining 3% of respondents said ‘don’t know’. Individuals were more likely than organisations to agree with the proposal (61% versus 50%). Conservation organisations almost universally agreed (97%). In addition, 69% of organisations in the ‘other organisation types’ category also agreed. By contrast, a large majority of land management, deer and sporting organisations (82%) disagreed.

| Yes | No | Don't know | Total | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Respondent type | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % |

| Land management, deer and sporting organisations | 7 | 14% | 41 | 82% | 2 | 4% | 50 | 100% |

| Conservation and animal welfare organisations | 32 | 97% | 0 | 0% | 1 | 3% | 33 | 100% |

| Other organisation types | 9 | 69% | 2 | 15% | 2 | 15% | 13 | 100% |

| Total organisations | 48 | 50% | 43 | 45% | 5 | 5% | 96 | 100% |

| Total individuals | 905 | 61% | 531 | 36% | 48 | 3% | 1,484 | 100% |

| Total, all respondents | 953 | 60% | 574 | 36% | 53 | 3% | 1,580 | 100% |

Percentages may not total 100% due to rounding.

A more detailed breakdown of responses by organisation type is shown in Annex 3, Table A3.9.

3.43 Question 7 included a follow-up question asking respondents who did not support cost recovery what alternative non-compliance measures, if any, they would recommend. It should be noted that most of the comments on this topic came from respondents who were not in favour of DMNROs, since most respondents who supported DMNROs were also in favour of cost recovery.

Views on cost recovery from respondents opposed to DMNROs

3.44 There were several recurring views expressed by respondents who opposed DMNROs. These respondents generally rejected the proposal that NatureScot should be able to recover the costs of intervening where a DMNRO has been issued and a landowner had not complied. Instead, they argued, incentives should be offered to landowners to encourage compliance. These respondents made the following points:

- Enhancement of the natural environment should be treated as a public benefit and achieved through appropriately implemented management incentives funded by the public purse. Financial incentives and adequate support are vital for delivering conservation activities in the public interest.

- NatureScot should continue to work with landowners on a voluntary basis.

- Current legislation already provides for deer control orders, and therefore no further control or legislation is required.

- Non-compliance measures could only be used if the assessment of poor deer management is fair and accurate. These respondents were generally sceptical of NatureScot’s ability to provide such an assessment.

- If reforestation or peatland restoration schemes require to be protected from deer, they should be fenced off and the cost covered by the relevant authorities responsible for those schemes.

3.45 It was also common for respondents in this group (and particularly individuals) to simply say that they did not support DMNROs and so did not support (or would not comment on) cost recovery or other non-compliance measures.

Views opposed to (or unsure about) cost recovery measures from respondents supporting DMNROs

3.46 A relatively small group of respondents who were in favour of DMNROs were not in favour of cost recovery, or they answered ‘don’t know’ at Question 7. These respondents made the following points:

- Not all landowners (particularly those with smaller landholdings) have the financial means or other resources to manage deer effectively.

- Any form of cost recovery should be proportionate to the means of the landowner.

- The problem of deer overpopulation – and also unfenced sheep – is a collective environmental and biodiversity problem for Scotland as a whole, not just for landowners and crofters. Passing the entire cost of addressing the problem onto landowners is unfair.

- As the proposed policy is government-driven and intended to benefit the wider community, the cost to implement it should be covered by the government from the public purse.

3.47 This group made a number of suggestions about alternatives to recovering costs from landowners who did not comply with a DMNRO. These included:

- Offering landowners grant funding or low-interest loans to enable them to comply

- Offsetting the cost of a deer stalker, hired by NatureScot, through the sale of venison

- Including deer management as part of SRDP (Scottish Rural Development Programme) compliance

- Having the costs of compliance shared between NatureScot and the landowner

- Selling permits for culling

- Using the services of local deer management groups

- Prohibiting estates from offering commercial deer stalking until there is compliance with the DMNRO.

Views on cost recovery measures from respondents supporting DMNROs

3.48 The follow-up question at Question 7 was not directed at respondents who were in favour of NatureScot being able to recover costs. Nonetheless, such respondents often made comments relevant to Question 7.

3.49 In general, the organisations in this group (mainly conservation organisations) did not discuss the question of cost recovery or alternative non-compliance measures. Instead, they argued that individuals subject to DMNROs should be eligible for financial support and advice to enable them to comply. However, they also suggested that this financial support should come with conditions. In particular, they thought incentives should:

- Be clearly linked to the delivery of public outcomes for sustainable deer management

- Go beyond reduction culls and support longer-term maintenance culls

- Not be used to pay for fencing (see the discussion of fencing below).

3.50 There was also a view that any funding should be directed to pay local stalkers, rather than being given to landowners to make their own arrangements.

3.51 Individual respondents in this group had a range of views on the subject of cost recovery and alternatives to cost recovery. In general, individuals advocated heavy fines/ financial penalties for non-compliance. However, some made the point that there would need to be a different approach for owners of large estates, compared to those with small holdings, and that financial penalties should be proportionate to the wealth/resources of the non-compliant landowner. Some individuals were opposed entirely to public money being used to support wealthy landowners to reduce deer numbers and so were not in favour of the use of incentives to encourage compliance.

3.52 In terms of alternatives to cost recovery, individual respondents made many of the same suggestions set out in paragraph 3.47 above. Additional suggestions included: (i) a carbon emissions land tax to be levied on estates with poor deer management practices, (ii) the ability by neighbours whose interests have been damaged to recover costs from a non-compliant landowner, (iii) removal of land-based emissions trading and/or grant scheme payments from non-compliant landowners, and (iv) compulsory purchase or ‘nationalisation’ of the land of a non-compliant landowner. There was also a suggestion that all deer management in Scotland on private land should be undertaken by NatureScot as standard practice and paid for by a tax on landowners.

Other comments (Q8)

3.53 Question 8 asked respondents for any further comments they had relating to enhancement of the natural environment through the use of DMNROs. Altogether, 514 respondents – 68 organisations and 446 individuals offered comments.[5]

3.54 There were three main themes in the responses. These related to (i) a need for clarity on the details and practical implementation of DMNROs, (ii) areas of priority for DMNROs, and (iii) fencing as a method of deer management. Each of these is discussed briefly below.

Need for clarity on DMNROs

3.55 Respondents of all types often said they wanted more clarity about how DMNROs would be applied in practice. Further details were requested in relation to:

- How areas for DMNROs would be identified (i.e. what circumstances/evidence would trigger them)

- How any new powers would interact with existing legislation (including existing Section 7 Agreements)[6] and wider land management policy (e.g. Regional Land Use Partnerships, Nature Networks, and other types of landscape scale focused policies and programmes)

- How DMNROs would be applied to single versus multiple landholdings to achieve the necessary benefits across a large area

- How data on deer populations and cull numbers would be managed under the proposed new system; it was thought that open access to this data would be useful to those responsible for land management

- The rights of crofters and common grazings committees and how these would be protected if a DMNRO were to be issued to a landlord

- Sanctions, penalty powers and the basis for appeals.

Areas of priority for DMNROs

3.56 While some respondents (i.e. a subset of those in favour of DMNROs) suggested the whole of Scotland should be subject to a DMNRO, others (mainly respondents from conservation organisations) made specific suggestions about areas that should be prioritised. These included:

- Riparian zones (areas around rivers, lakes and streams)

- Scotland’s temperate rainforest zone

- Peatlands.

3.57 In each of these cases, respondents said that ongoing initiatives to restore ecosystems were being hampered by the current (limited) level of voluntary deer control being undertaken by landowners.

Fencing as a method of deer management

3.58 A recurring theme in the comments – mainly from conservation organisations and some individuals – was the use of fencing as a method of deer management. This topic was seldom raised by land management organisations, deer groups, or sporting organisations.

3.59 Respondents noted that the consultation paper (and Question 4) proposed fencing as a deer management activity which may be required by a person subject to a DMNRO. This group expressed a range of concerns about this, including that:

- Deer fencing harms ecological systems by preventing wildlife from moving through the landscape. It traps larger wild animals in areas from which they cannot escape. For deer, this can cause distress and lead to starvation.

- Fencing has been implicated in the deaths of rare birds including capercaillie and black grouse.

- Fencing can break down as it ages and become a trip hazard for walkers and a danger for wildlife.

- Long stretches of deer fencing without gates or stiles can be a barrier to access and cause safety issues for hillwalkers and others using land for recreational purposes.

- The total exclusion of herbivores from existing rainforest sites can cause damage to mosses, lichens and invertebrates that require an open, lightly grazed, field layer.

- Deer fencing is expensive to install and maintain – one respondent noted that the cost of erecting deer fencing was more than double the grant funding available to pay for it.

3.60 A common theme in the comments from this group was that the requirement for deer fencing represented a failure in deer management and should only be used as a last resort, and on a temporary basis, to allow an area to recover naturally. The point was made that a fence is unlikely to work as a method of deer management without a cull on both sides of the fence – in which case, there is a question about whether it is really necessary. It was suggested that deer densities across Scotland should be brought down to a level whereby new planting schemes do not have to rely on protective fencing, and there was also a suggestion that any government grants for deer fencing should be redirected to support an enhanced deer stalking effort. Finally, there was a recurring view that the public purse should not pay for deer fencing in circumstances where a landowner wishes to maintain high deer numbers for sporting purposes.

Contact

Email: robyn.chapman@gov.scot

There is a problem

Thanks for your feedback