Market research of existing Civic Technologies for participation

Technologies to support citizen deliberation and participation form a growing market. This work has been commissioned to support the development of new technologies aimed at enhancing and scaling the use of the Scottish Government's Participation Framework for data governance.

Results

Our review covered 31 platforms that explicitly support citizen participation. The list below summarises all included platforms. The descriptions were reproduced from People’s Powered “platform highlights” or otherwise produced by the team.

Civic Tech platform and description

- 76 Engage: 76engage is a multilingual platform offering users various features. It has been used in various countries, including the United States, Canada, South Africa, Kenya, and Bangladesh.

- adhocracy+: Adhocracy+ is an open-source participation tool for citizen engagement. It allows organizations to inform and invite people to contribute ideas and provide data through surveys.

- Assembl: Assembl is a collective intelligence platform designed to facilitate large-scale consultation and in-depth debates.

- Bang the Table / Engagement HQ: Bang the Table is one of the oldest platforms on our list. It has a very large number of users and an impressive diversity of users by profile and geography.

- Cap Collectif: Cap Collectif is a debate tool which can be used to highlight different parts of the discussion and facilitate exchange of opinions. It offers users most of the features listed in our methodology, as well as the possibility to use a basic version via Purpoz.

- Go Vocal (formerly Citizen Lab): Citizen Lab is a platform that helps communities lead better online discussions and make decisions more inclusively using language processing and robust data analysis features. It is a younger platform with a rapid growth curve.

- Citizen OS: Citizen OS is a multilingual open-source platform focused on citizen-driven debates, discussions, and co-creation.

- Civocracy: Civocracy is a platform that creates space for productive long-term citizen cooperation with the local government, with a focus on feedback-gathering.

- Cobudget: Cobudget is an open-source platform for ideation, co-creation, and collective budgeting.

- Cocoriko: Cocoriko is a comprehensive consultation platform that allows people to engage in processes ranging from ideation to decision-making.

- Consider.it: Consider.it is a platform that visually summarises the opinions of the public and provides space for argument exchange and presentation of pros and cons.

- CONSUL: CONSUL is a comprehensive consultation platform that allows people to engage in processes ranging from ideation to decision-making.

- ConsultVox: ConsultVox is an accessible and intuitive tool for citizen participation.

- CoUrbanize: CoUrbanize is a platform tailored toward community engagement for development and planning. The Information Unavailable in the cost criterion indicates a lack of information about their cost plans.

- Decidim: Decidim is a comprehensive participation platform that allows people to engage in processes ranging from ideation to decision-making, including pre-tailored processes like participatory budgeting and citizens' assemblies. It is open source and has an extensive documentation and repositories of implementations of the platform.

- Delib: Delib is a comprehensive participation platform that allows people to engage in processes ranging from ideation to decision-making, with a unique simulator feature to engage people in complex decision-making and gathering, as well as sharing opinions and trade-offs associated with each decision. It is the oldest platform on the list.

- Democracy OS (Democracia en Red): Democracy OS (Democracia en Red) is an open-source tool primarily focusing on deliberation. It has been used in at least 10 countries, including Eswatini, El Salvador, Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Ecuador, Mexico and the United States.

- Discuto: Discuto is a platform that focuses on consensus-building through collaboration and discussion.

- Efalia Engage (Fluicity): Fluicity is a multilingual public consultation tech that has a special focus on participatory budgeting and idea gathering. It's been used in Angola, Belgium and France.

- Ethelo: Ethelo is a comprehensive participation platform that offers various features associated with different levels of engagement, from informing to decision-making. The Information Unavailable in the cost criterion indicates a lack of information about their cost plans.

- Konveio: Konveio is a dynamic engagement platform centred around working with complex documentation through informing, feedback gathering, and feedback analysis features.

- LiquidFeedback: LiquidFeedback is an open-source platform for proposal development and decision-making in medium and large groups.

- Loomio.: Loomio is an online decision-making platform that offers discussions, proposals, and feedback. It is open source and has clear data policies.

- Make.org: Make.org is a multilingual platform for large-scale online consultations that ensures balanced representation and

- diversity of participants. It has a high number of contributors and a large portion of large-scale international projects, including those that involve cross-border cooperation.

- Munipolis: Munipolis is an engagement and communication tech that allows citizens to continuously receive and provide important information. It's one of the oldest tools in Central and Eastern Europe, with among the largest numbers of users. The Information Unavailable in the cost criterion indicates a lack of information about their cost plans.

- Open Stad: Open Stad is an online engagement platform for a wide range of processes, including participatory budgeting, with a focus on informing and consensus-building through a choice guide feature.

- Participation / Decision21: Participation / Decision21 is one of the youngest online platforms for citizen participation. It covers a wide range of participatory projects, including participatory budgeting, and offers different voting methods.

- Pol.is: Pol.is is a platform for gathering, analyzing and understanding what large groups of people think in their own words, enabled by advanced statistics and machine learning. It is open source and provides good documentation in the "knowledge base."

- Social Pinpoint:S ocial Pinpoint is a comprehensive platform for participation with robust budgeting features. The Information Unavailable in the cost criterion indicates a lack of information about their cost plans.

- Your Priorities: Your Priorities is a consensus-driven platform with features such as the ability to add points in favor of or against each concept, voting for or against argumentative points, gamification of voting, and robust use of AI features. It is open source with a good "getting started" guide. It is one of the oldest and most established platforms, based on the number and diversity of users.

- Fora: Fora.io (previously known as the Local Voices Network) is a platform that focuses on hosting and creating analytics for small group dialogues and engagements. They combine automated translation and AI-powered analysis with human-led content analysis and create project web pages based on the results.

Technical features supporting citizen engagement

As Deseriis (2023) puts it, this sort of decision-making software embeds particular notions of participation into the software architecture by creating specific technical affordances for users and administrators. For example, Moats & Tseng (2024) found that the way that a specific Civic Tech (Pol.is) framed citizens' opinion in the case of Uber legalisation in Taiwan through "for" and "against" Uber positions pushed dichotomic thinking even when actual citizen opinions were much more nuanced.

In order to identify the features typically used by the Civic Techs included in this review, we adopted an abductive approach. This means we created and refined the list of features as new features appeared in the cases, going back and forth between our list and the available documentation. As we mentioned, we also reached out to companies and tested the technologies when we found ourselves in doubt.

Below we find the list of all features commonly identified in the platforms and their prevalence.

| Feature category | Feature | Total instances | % |

|---|---|---|---|

| Idea generation | Forums and Discussion Threads | 24 | 77.4 |

| Feedback and comment sections | 29 | 93.5 | |

| Open proposals / Crowdsourcing | 27 | 87.1 | |

| Idea selection | Open Voting | 16 | 51.6 |

| Polls and closed voting tools | 24 | 77.4 | |

| Prioritisation mechanisms | 21 | 67.7 | |

| Co-budgeting | 14 | 45.2 | |

| Assessment and descriptions | Mapping | 19 | 61.3 |

| Questionnaire/Surveys | 19 | 61.3 | |

| Text Co-review | 7 | 22.6 | |

| Platform Management | Moderation capabilities | 27 | 87.1 |

| Anonymous participation | 16 | 51.6 | |

| Soft verification (Login required) | 30 | 96.8 | |

| Hard verification — ID or e-ID | 8 | 25.8 | |

| User and role management | 26 | 83.9 | |

| Social communications and organising | Initiative tracking | 17 | 54.8 |

| Event organization tools | 12 | 38.7 | |

| Social media integration | 17 | 54.8 | |

| Embeddable Tool | 9 | 29.0 | |

| Newsletter | 17 | 54.8 | |

| Documentation | Engagement guidelines | 17 | 54.8 |

| Tech Documentation or Tutorials | 23 | 74.2 | |

| Data and Analytics | Export data | 15 | 48.4 |

| Demographic Analytics | 25 | 80.6 | |

| Participation Analytics | 15 | 48.4 | |

| APIs Services | 21 | 67.7 | |

| Customisation and inclusion support | Theming (Match brand identity) | 26 | 83.9 |

| Multilingual support | 17 | 54.8 | |

| Webpage builder | 9 | 29.0 | |

| Accessibility features | 14 | 45.2 | |

| AI support | AI - Grouping Data by Topic | 8 | 25.8 |

| AI - Sentiment Analysis | 7 | 22.6 | |

| AI - Automated Moderation | 1 | 3.2 | |

| AI - Chatbot | 2 | 6.5 |

We observe that across platforms, idea-generation features are quite common (present in 86% of total features). This means in practice, creating open text spaces for citizens to write and share opinions. Among idea selection features, polling is the most widely used (77%). Some platform management features are also quite common, particularly the creation of different user roles in general (83%), moderator roles for user-generated content specifically (87%), and login mechanisms (96%).

This concentration of features creates a picture that resonates with our experience with the tools. Most Civic Tech, especially those that are for general purpose, are technically set up as online forums with some credentialed access. These forums are expected to help citizens identify ideas by letting them write them down and commenting on each other's proposals. Against that background, it is safe to say that most Civic Tech tools are not technically complex from the informatics point of view, but rather, the complexity derives from the methodology used to prompt and sustain participation (the way in which the tools are used).

Social communications and organizing features were on average the least prevalent features in the review –excluding AI-specific tools, appearing in less than half the total features (46%). Documentation features also tend to be included in almost two-thirds the instances (64%). However, it is much more frequent that tools provide technical documentation (74%) than content documentation on participation (54%). This finding also resonates with our conclusion that many Civic Techs see themselves as neutral and agnostic spaces, for which the client will provide all necessary content and relational functionalities outside the platform.

Analytics are also somewhat common across platforms. Participation analytics are less common (48%), which in practice means visualised data on citizen interactions, compared to demographic analytics (80%), which visualises and describes the data on the volume of users and the information they provided about themselves. Some tools allow administrators to download both types of data in the export functions, which are also less common (48%). API integration is less common as well (48%) which speaks to data safety concerns, but most importantly, the lack of interoperability between technologies. However, the depth of analysis is quite varied across platforms. Specialist platforms like Consider.it and Polis are specialised in providing metrics and visualisations of consensus and disagreements among citizens. Projects like Talk to the City (which were not included due to their novelty) are advancing analytical funnels for substantive analysis of opinions through Topic Modelling, Sentiment Analysis, and Argument Mining among other text-mining techniques. However, in most cases, analytics tend to be thinner than what would be required for organisers to reconstruct public opinion. This is usually done through more advanced text-mining techniques such as argument-mining.

Customisation and inclusion support vary across features. Multilingual support is provided by some (83%), which in principle should be technically easy to provide because the underlying web design technology they use tends to already have that function. Webpage building for projects is less common (29%), but theming is much more prevalent (83%). Web building likely denotes companies that work closer with clients in developing tailor-made projects instead of selling off-the-shelf services. Of course, by tailor-made we refer to the organisational dimension because it does not imply substantial changes to the underlying technology.

Our review shows that AI features are scarcer still (14%). Out of the limited cases found in our review, we can observe that using AI for analytics, such as sentiment analysis (22%) or topic clustering (25%) is more frequent than citizen-facing AI through automated moderation (3%) or chatbots (6%). However, given the recent literature, it is likely that this area will grow in the near future.

Technical features throughout the citizen engagement cycle

In the previous section, we described the concentration of features according to the kind of support they provide (i.e. feature category). However, it is equally important to ask what part of the engagement process are these features supporting. In other words, where in the engagement cycle is support being provided by Civic Techs?

There are different ways to conceptualise the engagement cycle, but most of them converge in temporal division, organising in terms of things that happen before the engagement events, during the engagement events, and after the engagement events. For this review, we adapted Goñi et al. (2023) model consisting of four dialogical activities:

- Designing: Covers all early stages of the process, from inception to setting up the teams and preparing the materials for participation.

- Enacting: Covers all interactions and processes that occur once citizens have been invited until they come to conclusions or meet the objectives of the process.

- Analysis: Covers all processes and techniques used by organisers and other stakeholders to account for what happened, who took part and how they took part in order to inform others, typically ending in a report.

- Translating: Covers the use of the reports and outputs of the process to inform change, policy and political decisions. This can mean translation into the policy cycle or political impact in the public sphere, or other means of impact.

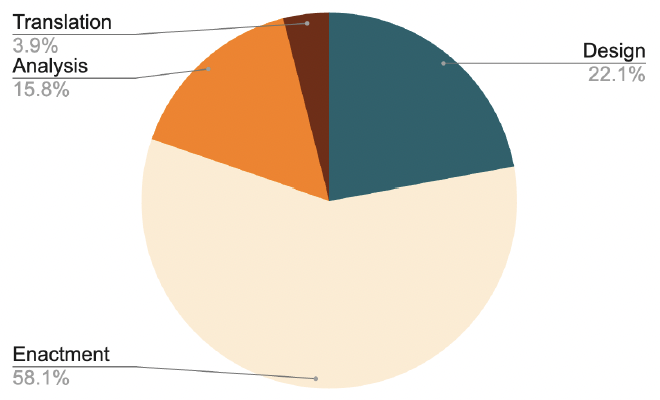

Using that guideline, we were able to code the features according to when they are meant to be used according to the public documentation of the tools. Some features are meant to be used consistently at the same stage of the process. For instance, moderation capabilities are consistently used for the enactment of engagement. In others, we observed dual use. For instance, mapping features can help organisers contextualise their process plan at the design stage, but it can also help participants enact their discussion. Equally, social media integration can help organisers tell the public about upcoming processes and generate momentum at the design stage, or it can be used to help the public sphere take up results in the translation stage. We guided our coding through how the tools represent the use while acknowledging that use will reshape the design in practice. With this in mind, our findings are shown in Figure 1.

Organised through the lens of the engagement process we can observe the degree of concentration of the features. More than half the instances of features we observed are meant to help the enactment of engagement (58%). In contrast, only 22% support design, 15% analysis and about 3% the translations of outputs into actual impact.

Enactment is covered quite extensively by idea generation and idea selection features, which are also quite common among platforms. Analysis features are concentrated on both participation and demographic analytics, as well as data export functions. Features to support and reflect on recruitment decisions were notably missing for the enactment of participation. Translation is mostly rare instances in which social media and newsletters are put in place to report on the political impact of participation. Nonetheless, given the complexities of political impact, it is safe to say that these functions are not sufficient to meet the complex needs of successful docking in political systems.

When we take a closer look, we can see that features supporting design are mostly related to project customisation, such as theming, web building and multilingual support accounting for roughly half the instances of design features (49%). This percentage increases to 64% when we add user and role management functions. In that sense, design support is mostly operationalised through the managerial dimension of participation. The most substantive way in which features support design is through engagement guidelines which account for 13% of instances of design features. However, as the name guidelines suggest, this is materialised mostly through reading materials over more interactive means of learning. It is also worth noting that any part of a platform which allows the user to configure an element of the enaction process is intrinsically permitting some amount of design.

Civic Tech business models

Civic Tech companies find themselves in a complex position in terms of market approach. On the one hand, many Civic Tech projects started from NGO, advocacy or even political activism and protest movements (Justice et al., 2018; Peixoto & Sifry, 2017; Russon Gilman & Carneiro Peixoto, 2019). Indeed, the “Civic Tech movement” finds inspiration in broader movements like Tech4Good, Data4Good, Open Government, and Participatory Governance (Turkel, 2020). Because of these, many projects have sought to open their inventions to the world through open-sourcing their codes, or through releasing them for free under a Creative Commons licencing.

On the other hand, as with any other business, they require a stable income to become sustainable over time. In practice, this means finding ways to sell their technology under a Software-as-a-Service (SaaS) scheme or receiving public funding to pay for their operations. This apparent tension does not mean that the market size for Civic Techs is negligible. According to the recent International IDEA report, in Europe alone, the market size was estimated at more than EUR 100 million in 2022, with a five-year growth expectation of EUR 300 million (García, 2023).

Below we showcase our findings regarding how Civic Tech companies structure their business models. For this, we separate business models in three dimensions: Hosting model (whether people can use the technology on their own or if they require credentials from the company), Business strategy (how the company looks for income), and Property and licensing model (how the company manages its intellectual property). Table 2 shows the results.

| Model dimension | Type | Description | Total (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hosting model | Account-based SaaS | Account based-service where the user gains access to usage of the software | 28 (93%) |

| Self-deployable | The platform can be fully hosted and deployed by any external actor | 12 (40%) | |

| Business strategy | Traditional SaaS | The core features of the platform are offered at a single price point | 11 (36%) |

| Feature-based tiers | Different tiers containing different features are offered at different prices | 11 (36%) | |

| Paid support | Technical support is offered to help run the platform | 18 (60%) | |

| Consultancy fees | Technical support around participation is offered to design the overall project | 15 (50%) | |

| Institutionally funded | Public institutions provide direct economic support to the platform | 7 (23%) | |

| Donation-based | The platform is funded by individuals, charities and/or foundations | 8 (26%) | |

| Zero Maintenance | The platform only makes the tool available providing no support or services for use | 3 (10%) | |

| Property and licencing model | Proprietary | The code is closed and owned by the software company | 14 (46%) |

| Open Core | The main features of the platform are open source but not all | 1 (3.3%) | |

| Fully open source | All relevant features and components are open-source | 16 (53%) |

Generally, we can see that a diversity of business models coexists in the Civic Tech space. In terms of hosting, most Civic Tech organisations offer hosting services themselves (93%), and only a slight minority (40%) of tools can be self-deployed. In that sense, despite the split between technologies that are made available to all users and technologies that operate with greater gatekeeping by the organisation, the Software-as-a-Service (SaaS) model is pervasive across all of them.

This split can also be observed in the property and licencing models of technologies. While a slight majority of tools included in this review provide a repository (mainly in Github) of all their relevant code (53%) or at least their main features (one instance), a significant number of tools are structured as proprietary and closed.

A greater diversity of paths can be observed in the business strategies of the tools, meaning, how the organisations pursue and create revenue streams. Here, we see an organisation of thirds. One third of the organisations "rent" the whole software and its features in a single package (36%). Another third uses a tier-based approach to offer different features at different price points (36%) – in some instances, but not all, the lowest tier is offered for free. Finally, another third of organisations are set up to offer the technology for free to end users and seek funding primarily through donations (26%).

In that sense, we observe a clear division of how Civic Techs are structured. On the one hand, half the cases we review fall under the logic of the digital commons, meaning they strive to create open data infrastructures and free-to-use technology. Another half of the cases are set up as traditional Software-as-a-Service companies, with some IP protection and making revenue either selling the technology as a whole or with the tier-based approach, complementing with consultancy on top as well.

Technological and ethical maturity

Given the sensitivity of working with external organisations to run policy-informing public engagement, it becomes a necessity to not just match technical features to organiser necessities, but also to trust the technical and ethical reliability of the technology to deliver on its promises.

As a complementary analysis, in the below table, we reproduce People Powered’s analysis to explore the technical and ethical reliability of the Civic Tech tools. This excludes the tools which we added on top of the original People Powered rankings.

| Platform name | Track Record & Reliability Score: 0-100 | Ethics & Transparency Score: 0-100 |

|---|---|---|

| 76 Engage | 49 | 44 |

| adhocracy+ | 69 | 97 |

| Assembl | 68 | N/A |

| Bang the Table / Engagement HQ | 89 | N/A |

| Cap Collectif | 70 | 83 |

| Go Vocal (formerly Citizen Lab) | 76 | 73 |

| Citizen OS | 64 | 83 |

| Civocracy | 76 | 60 |

| Cobudget | 53 | 57 |

| Cocoriko | 42 | 53 |

| Consider.it | 60 | 100 |

| CONSUL | 87 | 97 |

| ConsultVox | 76 | 53 |

| CoUrbanize | 76 | 40 |

| Decidim | 87 | 100 |

| Delib | 89 | 70 |

| Democracia OS | 64 | 73 |

| Discuto | 53 | 53 |

| Efalia Engage (Fluicity) | 76 | 70 |

| Ethelo | 82 | 60 |

| Konveio. | 69 | 67 |

| LiquidFeedback | 60 | 73 |

| Loomio. | 93 | 100 |

| Make.org | 87 | 90 |

| Munipolis | 82 | 50 |

| Open Stad | 53 | 77 |

| Participation / Decision21 | 76 | 33 |

| Pol.is | 64 | 80 |

| Social Pinpoint | 76 | 70 |

| Your Priorities | 100 | 97 |

*N/A responses if the 2024 People Powered rankings does not provide a score for that platform

In terms of technological maturity, it can broadly be stated that all systems evaluated are operational (TRL 9), with a credible track record and not at the prototype stage. To have a more specific assessment, we relied on People Powered’s 2024 ranking dimension of "Track record and reliability" as a proxy for the degree of maturity in the market.

People Powered assigns points on this dimension from 0 to 100 based on three variables:

- Length of time on the market.

- Profile and breakdown of institutional users

- Diversity of contributors.

Using these threefold criteria, we can observe that technologies such as Your Priorities (100), Loomio (93), Engagement HQ (89), and Delib (89) come on top. From our research, the reasons are varied. Technologies such as Your Priorities have become widely used globally, for a long time now. Companies such as Delib rank higher than others due to it being one of the oldest operations. And then, there are Civic Tech companies, such as Loomio or Engagement HQ, that have been structured as large organisations. This means that they cover more clients (thus rank higher in the profile of users), and hire more personnel (thus rank higher in diversity of contributors).

However, these results may be misleading. In our research, we got to test the technologies and speak to organisations that rank much lower in this ranking (even lower than 50). What we found is that it is not necessarily a matter of less maturity or reliability that is captured by this ranking. Some companies are simply structured in a qualitatively different manner. For instance, 76 Engage was founded in 2015 and is conceived as a small and more “boutique” service that depends on highly customised projects. Because of this, it may rank lower in diversity of actors and contributors. It is not clear this captures their organizational or technological track record, if we consider, for instance, how much this organisation has spent in integrating professional standards via their collaboration with one of the largest participation associations (IA2P).

On the other hand, bigger technologies such as Engagement HQ operate in the same area. They likely score higher, among other reasons, for being longer in the business –since 2008. However, this platform has experienced a lot of transformations throughout the years. In fact, in 2021 they were acquired by one of the largest GovTech vendors worldwide (Granicus). As any other big public sector vendor, Granicus works with a wider array of services, in which participation is just one of the many options. This is not to say that they offer a lesser quality service. Our finding suggests that track records and technological maturity must be understood in the context of qualitative differences in how companies structure their business.

In terms of ethical maturity, we centred our analysis on the People Powered dimension of “Ethics and transparency”. This dimension is scored from 0-100 based on five variables:

- Open source and open licencing of core code.

- Data policy around informing users of data use and selling data to third parties

- Data protection from leaks and attacks

- Transparency of moderation against harmful or hate speech

- Raw data export function

These dimensions cover a wide variety of issues concerning explanations and regulations of citizen behaviour, as well as relations between technology and other societal actors. Technologies such as Decidim succeed in this ranking because not only do they provide detailed documentation of their code and data usage, but they are also quite concerned with their governance structure. For instance, each official partner of Decidim (service or technology providers working on their tool) will be required to sign a social contract as well as a legal one in which they explain and ask signees to adhere to their core values of openness and transparency. Moreover, people and organisations that use their technology can join the Metadecidim assembly that democratically runs the governance of the platform.

The case of Decidim is interesting in that it speaks to how ethical considerations can go far beyond the requirement to have a clear and public data policy facing the users. The sort of measures used by Decidim are exceptional to the Civic Tech space. Other highly ranked platforms such as Loomio, which is run as a work cooperative, use open code and have very clear data compliance policies. However, no platform comes close to the degree of inter-organisational collaboration exhibited by Decidim and its user-governance community.

Overall, we observe that new technologies in this space face ethical challenges that exceed legal compliance. For instance, this is the case if we consider the ethical value of collaboration. There has been a growing interest in the interoperability of democratic engagement tools, such that the system can learn and build upon existing work. Another key element that is underrepresented in the tools is the co-production of ethical norms. Given that they operate in the participatory space, it seems fundamental that tools explore ways in which users and communities can embed some of their ethical norms into the product design. This is even more the case when we consider that the tools are used worldwide by different cultures on different continents.

Contact

Email: tom.wilkinson@gov.scot

There is a problem

Thanks for your feedback