Minimum Unit Pricing (MUP) Continuation and future pricing: Business and Regulatory Impact Assessment

Scottish Government developed a Business and Regulatory Impact Assessment to analyse the costs and benefits of the continuation and uprating of Minimum Unit Price (MUP) on businesses.

8. COMPETITION ASSESSMENT

Introduction

This competition assessment analyses the likely economic impact of setting the minimum price per unit of alcohol to 65puu on the competitive ability of producers and retailers and the consequential impact on consumers.

Definition of competition

Competition is a process of rivalry between firms seeking to win customers’ business. Effective competition encourages firms to deliver benefits to customers in terms of prices, quality and choice. Competition also provides strong incentives for firms to innovate and to improve productivity[158]. Where levels of rivalry are reduced (say because a proposal restricts the number of firms active in any market) consumers have less choice because they have fewer firms from which they can buy goods or services.

Firms compete for market share using both price and non-price competition. Competition between firms may focus on offering the lowest price, particularly where the product is standardised (either because of the characteristics of the product in question, or because of regulation). Most suppliers will try and compete in a number of ways in addition to price through product differentiation and market segmentation. For instance, developing new ‘improved’ products, offering products of differing quality or characteristics, branding and advertising the differences in their products relative to their competitors’, or using different sales channels.

However, left wholly unregulated, markets will not necessarily deliver the best outcomes for consumers, companies, or the government. Government has a legitimate role in intervening and shaping them: it also intervenes more widely to achieve other policy goals and correct market failures.

Definition of markets

Markets and sectors which could potentially be affected both directly (downstream) and indirectly (upstream) have been identified and are listed below.

Directly affected markets/sectors (downstream):

- Sales of alcohol on off-licensed premises (off-trade)

- Sales of alcohol in licensed premises (on-trade)

- Market flows between on and off-licensed sales

- Sales of other products by retailers which sell alcohol, including footfall

- Consumers ability to access low-cost products.

Indirectly affected sectors (upstream) include:

- Distributors/wholesalers

- Producers

- Raw material suppliers

Overview of the Scottish drinks industry

The structure of the Scottish alcoholic drinks industry is complex. On the manufacturing side, broadly reflecting the global market, multinational companies producing multiple products for different worldwide markets dominate; and there are then a large number of smaller producers. These firms, in turn, use a large number of smaller firms, from Scotland, the rest of the UK, or abroad, to supply the required inputs for the production process and in some cases may subcontract out part of the production process, such as bottling, to other firms.

The Scottish firms impact test gives a detailed overview of the Scottish drinks industry – see section 7.

Market concentration

The Scottish off-trade alcohol products market is highly concentrated, with a small number of large international producers dominating sales, particularly for beer, cider and spirits.

The Scottish retail market is also highly concentrated. It is estimated that large, multiple retailers (supermarkets) account for approximately 80% of total off-trade alcohol sales in Scotland[159]. In the year before MUP was first implemented (May 2017 to April 2018 inclusive), the top 50 brands in supermarkets accounted for 67.3% of all supermarket alcohol sales (natural volume per adult), while in the convenience sample they accounted for 79.9%.

Together, the top 50 brands are estimated to make up 59.2 per cent of total supermarket and convenience alcohol sales volume of pure alcohol in 2022 in Scotland [160]. Off-trade sales overall make up 85 per cent of the volume of pure alcohol sold in Scotland in 2021, while the average price per unit in the on-trade was £2.04 in 2021 meaning there is unlikely to be any direct impact of MUP on the sector[161]. It should be noted Covid-19 restrictions during this period increased the share of pure alcohol sold in the off-trade relative to the on-trade, with around three quarters of pure alcohol volume sold via the off-trade prior to the pandemic.

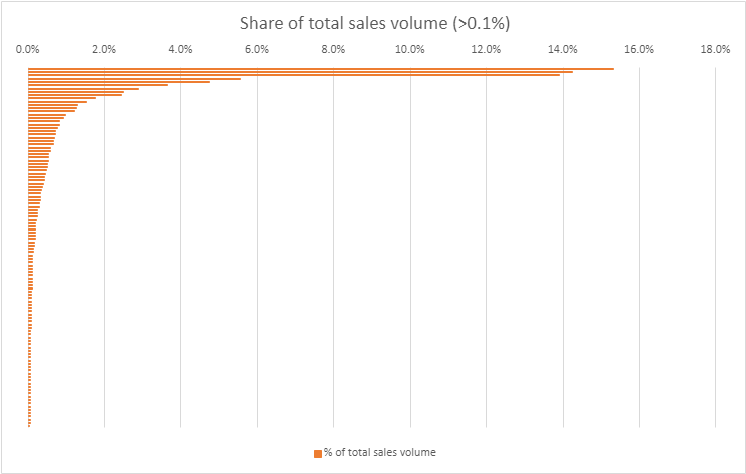

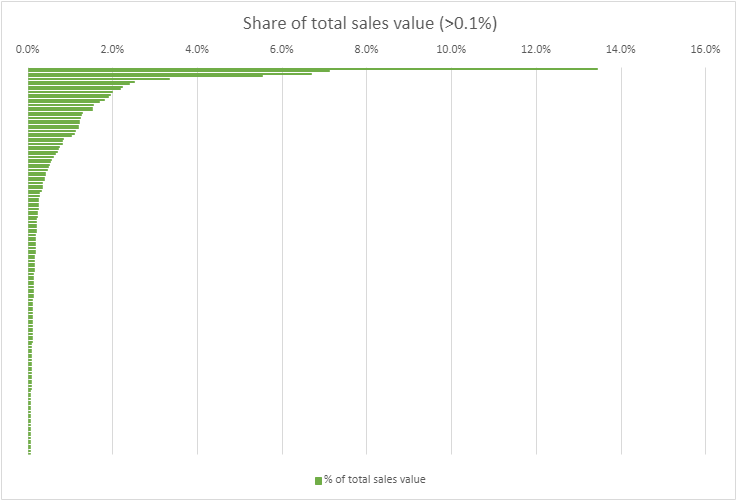

Analysis of 2022 off-trade sales data highlights the concentration of sales in producers. We estimate that 67% of sales by volume of alcohol came from just 10 companies. The market is less concentrated when considering by the value of sales, with 44% of the value of sales coming from 10 companies.

The distribution of off-trade sales by manufacturer in 2022 is shown in Figure 13 below and Figure 14 by volume of alcohol and value of sales.

Prices

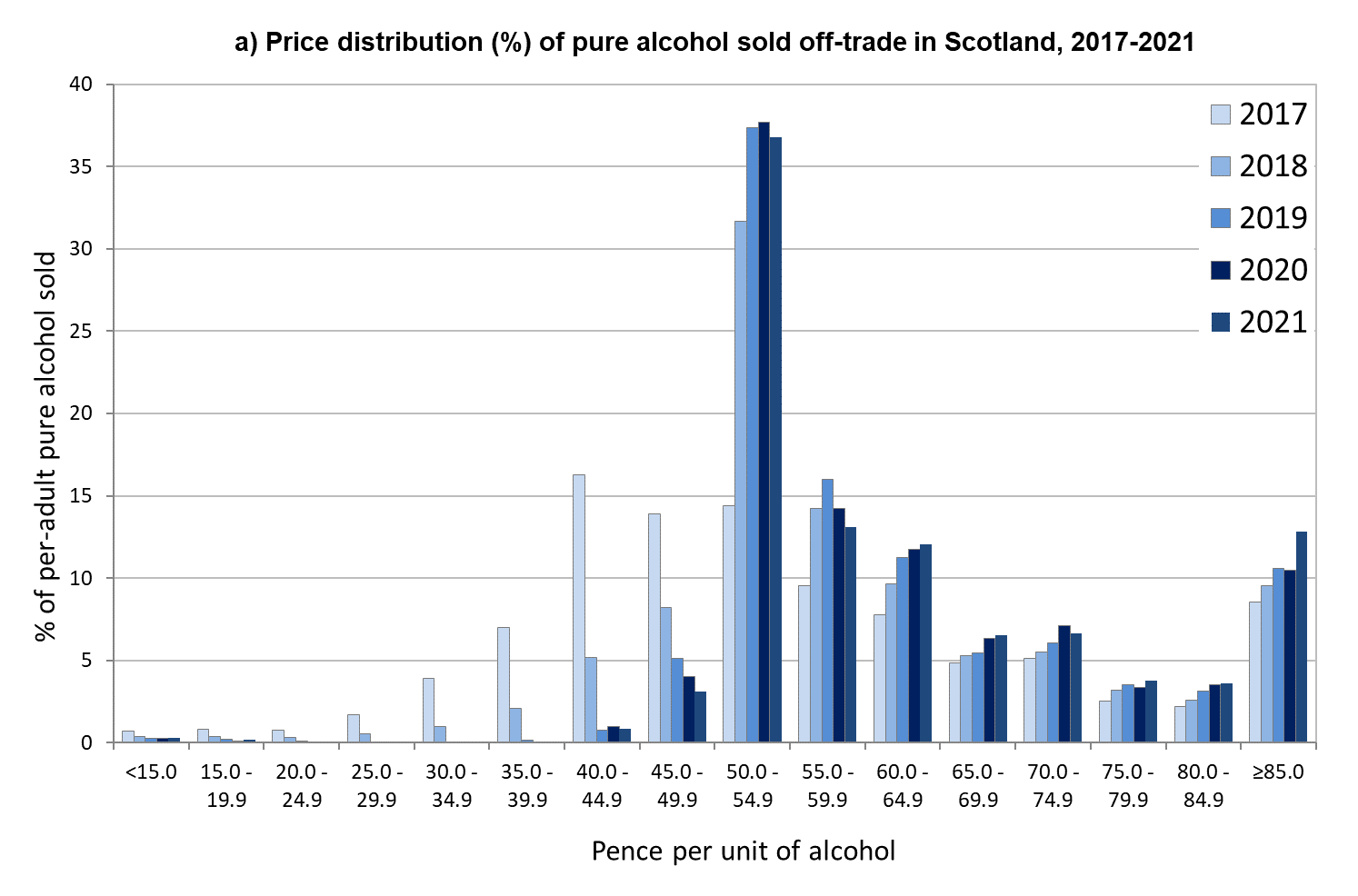

Average prices are one indicator of the price level in the market but are not sufficient to allow an assessment of the likely impact of the move to a 65ppu minimum price. Data on the distribution of prices (expressed as the price of a unit of pure alcohol) is required.

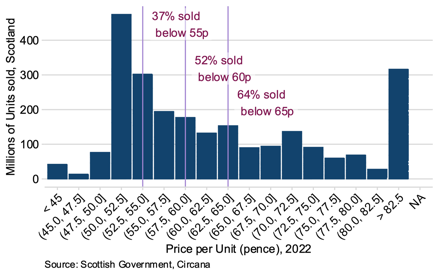

Figure 15 shows the price distribution of the off-trade market in Scotland for 2022 (by volume of pure alcohol). This highlights that in 2022, 64% of off-trade products were sold below 65ppu. For comparison, in 2017, ahead of the introduction of MUP, 45% of products were sold below 50ppu, while in 2012 when the policy was being original considered it was around 60%.

The more concentrated the market gets as a result of a Minimum Unit Price floor, the greater the impact will be on competition and the market. Products which currently compete to attract demand by charging a low price will no longer be able to do so to the same extent. If products of different quality – assumed by the current difference in price – are sold at the same price, due to the increase in MUP it will likely see demand, while lower overall, shift to the previously higher priced products.

For reference, in 2008 when MUP in Scotland was first under development, 81% of all off-trade alcohol was sold at below 50p per unit. Between 2009 and 2013 the percentage declined steadily (e.g. to 73% in 2010). But this decline slowed thereafter with 52% sold under 50p per unit in 2014 and 51% in 2016.

The shift to a bimodal distribution was due to the impact of substantial numbers of products clustering around price points e.g. a bottle of spirits (ABV 37.5%) retailing at £11 was equivalent to 42ppu; a bottle of wine (ABV 12.5%) retailing at £5 was equivalent to 53ppu (Figure 17).

The introduction of minimum unit pricing in 2018 led to a clear rightwards shift in the price distribution as products could no longer be sold below 50ppu. This also removed the bimodal distribution seen prior to minimum unit pricing.

The expected general shift to the right as cash prices of alcohol products increase can be seen at the higher end of the price distributions from 2018 onwards (Figure 18). However, as many products currently at the minimum price level would be able to profitability sell for below 50ppu the share of products at that level has remained relatively stable since 2018, leaving the relatively condensed price distribution.

Cross-border sales

Significant price changes and price differentials across borders can encourage cross-border trade in alcohol[162]. While the Minimum Unit Price of alcohol is in place in Scotland but not England there is potential for Scottish consumers to purchase alcoholic products in off-licences across the border, thereby shifting market demand away from Scottish supply (cross-border effects).

The likelihood of this occurring depends on consumers’ willingness to travel for their alcohol purchases (both in terms of the cost of travel in terms of transportation and time taken) and on the scale of the price differential between products in either country.

At 65ppu, the products most likely to be affected are high-strength, low price products and potential savings from purchasing these products in England would have to be weighed against the travel and transport costs incurred. All else equal, the higher the level of minimum unit price the greater share of products would face a price difference and the magnitude of the price differential would increase.

There is no strong evidence to suggest that there has been a substantial increase in cross-border sales since MUP was introduced in 2018. Qualitative interviews with retailers in towns near the Scottish/English border suggest that some Scottish consumers may have increased alcohol purchases in England after MUP was introduced in Scotland in 2018, but such cross-border sales accounted for a very small proportion of overall purchases.[163] PHS carried out a survey of cross-border purchasing of alcohol in March 2021[164] and the results are consistent with these findings. The survey was repeated in March 2022[165] with similar results.

As set out in the Costs and Benefits section, increasing the MUP to 65ppu is a real terms increase in the level compared to when MUP was first introduced. This would increase the price differentials between the cheapest alcohol either side of the Scotland England border, and therefore will increase the potential incentives for cross-border purchases due to increased savings available.

Internet sales

Another potential consequence of MUP applying in Scotland and not England is an increase in internet sales. If the alcohol is despatched from within Scotland, minimum pricing applies (as it is a condition of the licence) e.g. weekly grocery shop or local home delivery service. If despatched from outwith Scotland e.g. a wine club based in England, it will not apply. Similar to cross-border shopping, the incentive to buy from outwith Scotland via the internet will be greater the bigger the price differential between the price of alcohol in Scotland and elsewhere, combined with the volume of goods being purchased.

PHS conducted an analysis of the price differential between products available online in comparison to in Scottish retail premises[166] [167].

Analysis in July 2020 found eight of the 18 products were available below 50ppu when purchased online and none were available below 50ppu when purchased in the supermarkets was included.

However, at the time of data collection (July 2020) most of the alcoholic beverages that were available below 50 pence per unit when purchasing online required bulk purchase, often at significant cost, in order to take advantage of a price that was lower than the minimum price. As noted above it was possible to do so if the products were dispatched from places in the UK where MUP does not apply.

Distribution centres which are based in Scotland fall within the scope of the Licensing (Scotland) Act 2005[168]. The increase in online retailing has also resulted in an expanded logistics structure, with more distribution centres being built and used in Scotland. For example, Amazon was granted premises licences for distribution centres in Scotland, bringing them in scope of the Licensing (Scotland) Act 2005[169].

Nevertheless, this remains a market segment which will require careful monitoring as the market continues to develop and the potential price differential grows with the increased minimum unit price level to 65ppu. It was noted in the economic impact study that the pandemic has driven significant changes in online shopping, with more people buying alcohol online than previously.

Impact on retailers, suppliers and wholesalers

Guidance produced by the Competition and Markets Authority recommends the consideration of four key questions in order to discuss whether the legislation on alcohol products would have an impact on competition[170]. Each of these questions is discussed in turn for the proposal of a 65ppu minimum price of alcohol.

The four questions are as follows. In any affected market, would the proposals:

1. Directly or indirectly limit the number or range of suppliers?

2. Limit the ability of suppliers to compete?

3. Limit suppliers’ incentives to compete vigorously?

4. Limit the choices and information available to the consumer?

1. Would the proposals directly or indirectly limit the number or range of suppliers?

Minimum unit pricing does not award exclusive rights to supply or restrict procurement processes to a single supplier or restricted group of suppliers. There is also no direct impact or limitation (quota) on the number of suppliers or retailers as a consequence of the policy.

A licensing scheme is already in place for the retail of alcohol in off-sales and on-sales premises. Minimum unit pricing affects all off and on-sales licensed premises as it will continue to be a mandatory condition of a licence, however, it does not affect the existing licensing scheme or require the introduction of a new licensing scheme.

The minimum unit price has established a price floor for alcoholic drinks based on their units of alcohol. The increase in minimum unit price could potentially make it harder for firms to enter or exit the market for producing or retailing alcohol if the price floor is binding, i.e. if the ‘free market’ price for their product lies below the preferred price floor. This could prevent low-cost producers from using their cost advantage to enter the market. New entrants would no longer be able to attract demand by challenging existing firms on price, and products below the minimum price would be left with the ability to compete only on non-price factors such as brand, quality, range, advertising, etc. So it may, indirectly, act as a barrier to entry for new firms.

Although conversely, for low-cost producers, retailers may continue to be attracted to their products. If the low cost of production continues to be reflected in the price charged to the retailer, there will be the potential for increased levels of profit per item.

Products that currently retail below the 65ppu will require to raise their price to comply with the legislation. This could result in a number of brands of a similar product retailing at an identical price such as supermarket own/ private label spirits, brands currently associated with a low retail price and those recognised as more premium brands. If there was no price differential it may be that demand for the own/ private label product or value product diminishes leading ultimately to a reduction in the number of suppliers.

Research following the introduction of MUP at 50ppu found mixed evidence about the impact on own-brand products[171]. Industry interviews with some producers found that contrary to forecasts that own-label would have less relevance due to MUP there was in fact a significant growth in the own-brands in large retailers – although the extent of MUP on this finding was unclear.

Conversely, a large retailer interviewed felt their tertiary own-brand range (brands designed to be similar to leading brands) had been squeezed as there was no point in selling a product if it was unable to be retailed for a more affordable price.

This suggests some different viewpoints among producers and retailers on the longer-term impacts of MUP on the own-brand segment. The impact going forward will also clearly be impacted by the degree to which the minimum unit price increase compresses the price distribution of products.

2. Would the proposal limit the ability of suppliers to compete?

Minimum unit pricing restricts the ability of retailers to price alcohol products on the basis of their alcohol content. Since the limitation acts as a price floor, retailers are not able to out-compete through undercutting one another on price across some or all of their product range or through loss-leading (i.e. below cost selling) using a price level below the floor.

While in theory this could present a weakening effect on competition between retailers, there is no strong evidence that the introduction of the 50ppu minimum unit price in 2018 was responsible for any significant detrimental impact to competition.

Identifying which part of the retail market will be most affected by the change to the level of MUP – supermarkets or small shops – is challenging. Large and small retailers are likely to be affected differently. Larger retailers sell large volumes of popular brands (often priced very competitively) but also, a greater range of products. Convenience stores’ representatives have previously said that they need to maintain low prices to compete with supermarkets, particularly as supermarkets continue to develop their “convenience store” format.

The Scottish Government is aware from the introduction of MUP at 50ppu that the gap between the prices in convenience stores and supermarkets narrowed[172]. The average price per unit of alcohol in Scotland increased from £0.60 in the year prior to MUP being implemented to £0.66 in the year following - primarily driven by the supermarket sector where the average price increased from £0.56 per unit in the year prior to MUP implementation, to £0.66 in the year following (+17.9%). On average, alcohol sold through convenience stores was more expensive than that sold in supermarkets prior to MUP being implemented, but saw a smaller change in average price from £0.63 to £0.67 (+6.3%). This resulted in a similar average price per unit in supermarkets and convenience stores in Scotland during the first year following the introduction of MUP.

The economic impact study reported that views were mixed on the extent to which the market share of different retailers had changed as a result of MUP in 2018, and there was little evidence to suggest significant changes had taken place. Most of the respondents could see the potential benefits MUP offered for smaller retailers, by offering parity in terms of price and opportunities for promotions. The large retailers also believed they lost some market share when MUP was initially introduced as Scotland has a large convenience footprint and the level playing field gave convenience stores a marketing opportunity, while a few smaller retailers felt MUP had limited their opportunity to offer promotions just as much as the larger retailers.

It is very unlikely that the continuation of minimum price legislation would force any small retailers out of the market. In any exceptional circumstances where this was the case, there would be a potential competition impact since it could lead to a more consolidated market, and hence less competition between firms even on products where the minimum price floor does not have a direct effect.

The initial change in the market is likely to be in the quantities sold of a specific alcoholic product if the original price lay below 65ppu. The change in revenue to retailers and wholesalers will be determined by consumers’ elasticity of demand for that product – the more inelastic the demand, the greater the increase in revenue. This leads to a transfer of ‘rents’ from consumers to retailers. In effect, retailers can charge higher prices for the same goods than they otherwise could under free and unrestricted competitive markets.

With minimum unit pricing potentially reducing the relative price gap between lower and higher quality products another form of market distortion that has been raised by industry previously is the potential for increased ‘commoditisation[173]’, with a compressed price distribution leading to less ability for consumers to identify the premium products.

An alternative scenario could be a proportionate increase in prices of higher quality products by retailers in order to maintain product differentiation, which would then result in a higher level of prices throughout the alcohol product segment presented to the consumer.

Evidence from British Columbia shows that when the minimum price for alcoholic drinks was raised, prices rose across all of the price distribution, including those well above the minimum price. The scale of price increases reduced the higher the original price of the product[174].

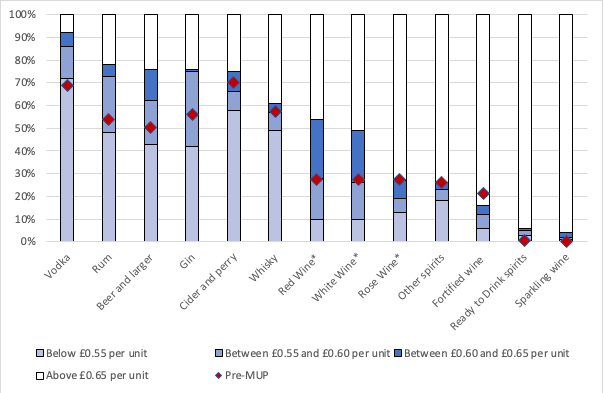

However, following the introduction of MUP in Scotland at 50ppu in May 2018, it was alcoholic drink products with the lowest price per unit of alcohol before MUP that saw the greatest increases. This particularly affected the cider (+25.6%) and perry (+50.0%) categories as well as own-brand spirits in supermarkets, such as own-brand vodka (+18.5%), gin (+16.1%), and blended whisky (+12.8%)[175].

The economic impact study also found that the trend of increased premiumisation continued following MUP, with most industry respondents highlighting there was a shift towards a new equilibrium of lower volume and higher value sales in the alcoholic drinks sector.[176] The price compression MUP created was seen as one of the many contributing factors to this trend, and both retailers and producers were positive about the impact of this as it was consistent with their marketing and growth strategies.

The likely behavioural response to the increase in price is discussed in detail in the section on elasticities. Overall demand for alcohol tends to be inelastic. This mean that an increased price leads to a proportionately smaller decrease in demand and an increase in revenue.

The most recent estimates from the Sheffield Model are that, after accounting for duty and VAT, a minimum unit price of 65ppu would lead to an increase in overall industry revenues compared to when MUP was introduced in 2018, all else being equal. The modelling also estimates that there would be a decrease in exchequer receipts compared to when MUP was introduced in 2018, all else being equal.

The likely distribution of industry revenues across the supply chain is not known. If the majority of profits are retained by retailers – as was seen with the introduction of MUP at 50ppu - margins would return to broadly similar levels to when MUP was introduced in 2018 and could be used to become more competitive in other areas, (e.g. fruit and vegetables). It might lead to loss-leading activities on staple items such as bread and milk.

This might put smaller retailers, who would not have the same flexibility of margins, at a competitive disadvantage. If producers raise their prices accordingly following the imposition of a minimum price, this could negate any profit margin increase for retailers.

However, the PHS economic impact evaluation found there was little evidence that retailers had shared any MUP surplus with consumers by discounting non-alcoholic products[177].

The evaluation found that producer-retailer relationships have remained consistent since the introduction of MUP[178]. While initially some retailers would ask producers specific questions about products in relation to implementing MUP, over time they have made their own decisions about price points. Producers continue to find that large retailers are still unwilling to pass on any potential profits from MUP increases, while smaller retailers noted no change in their relationships with wholesalers, who they typically found would not negotiate on price. In addition, the use of price-marked products further limited opportunities to negotiate.

In some cases, there is a risk that Government-imposed restrictions on pricing could encourage rent-seeking activity e.g. lobbying by firms to maintain or increase restrictions. This could lead retailers to divert resources away from developing and improving their products and services. In the long-run this can result in higher costs. Raising the minimum unit price level above the rate of alcohol inflation would bring more products into scope of the regulations and therefore has the potential to increase this behaviour.

Production methods and innovation

The producers that will be most affected by a minimum price change are those whose production consists of a significant volume of products which currently sell below theupdated minimum price threshold of 65ppu. These producers are likely to be the ones whose main production focuses on own/private label products, as these generally sell at lower prices.

There should be minimal negative impact on innovation or the introduction of new products. New, high-strength products would have to comply with the new minimum price, but would not be prevented from being introduced. There may even be an incentive to innovate. One possible effect of the updated minimum price could be the introduction of alcohol products containing lower strength alcohol which could be sold at a relatively lower price in larger quantities due to them containing fewer units of alcohol per litre. This would constitute an introduction of a new product in line with proposed legislation and would not change the characteristics of existing products. However, reducing the alcohol content will not be an option for some products such as Scotch Whisky, where legal definitions dictate that the product has to be of strength of at least 40% or higher[179].

In the year following the introduction of MUP, there were more products (at the brand level) discontinued compared to the corresponding period prior to MUP (27 compared to 32, with 506 unique products at baseline). Similarly, there were more products introduced in the year prior to MUP compared to the year after (52 compared to 33). It was also found that only a small proportion of products in Scotland, approximately 4.4%, had a change in ABV in February 2019 compared to February 2018.[180]

Case studies and interviews with the sector highlighted that the changes were most likely in the form of new format sizes and pack sizes to meet attractive price points rather than product reformulation. Changes in products and strategies were limited due to Scotland representing only a small share of many of the firms’ businesses.[181]

It is not anticipated that the proposals will limit suppliers' freedoms to organise their own production processes or their choice of organisational form.

International competition

In the consultation prior to the initial introduction of minimum unit pricing in 2018 there was some concern raised by the industry[182] that the introduction of the MUP legislation in Scotland set a precedent which could lead to similar legislation being introduced in other countries, on the basis of a public health rationale.

Since its introduction in Scotland in 2018, minimum unit pricing legislation has been introduced in Wales, Republic of Ireland, and the Northern Territory, Australia. The extent to which this would have happened anyway is unclear.

While there could potentially be a detrimental effect on the export segment of Scottish drinks producers if the price floor outside of Scotland fell below the ‘free market’ price, the current minimum unit prices in Wales (50ppu) and the Republic of Ireland (10 cents (euro) per gram which is equivalent to around 70ppu[183]) would be unlikely to have a significant impact on Scotland’s primary alcohol export of Scotch Whisky. Also, Scotch Whisky is already subject to a number of imposed duties and restrictions in other countries, so it is difficult to see how minimum pricing introduces a precedent.

3. Would the proposals reduce suppliers’ incentives to compete vigorously?

The primary effect of a price floor is to reduce the ability of retailers to compete on price grounds in a certain section of the market. Changing the minimum unit level would change the section of the market where retailers are no longer able to compete on price. Instead, retailers might switch to competing on other factors, such as customer service, quality, heritage, taste or origin. Some of this could be positive for consumers. However, other forms of competition can be less positive (e.g. competition on advertising). There has been no strong evidence that the introduction of MUP at 50p per unit in 2018 has led to any significant increase in non-price competition. All else equal, an increase in the level of price will lower the number of products which can be used to compete for custom via price, with the potential unintended consequence of increase in this type of non-price competition facilitated by the increase in revenue and any resultant impact on sales.

The Scottish Government has established that at 65ppu the impact on retailer revenues would likely be broadly positive (i.e. an overall increase) compared to when MUP was introduced in 2018 at 50ppu. However, the ability to compete on price diminishes as a greater share of products are brought under the minimum unit level, and at 65ppu this share is likely to be slightly larger than when MUP was first introduced (64% in 2022, 45% in 2017).

At the introduction of the minimum price it was noted that it was important to not inadvertently allow or encourage competitors to share information on their commercial matters (e.g. future price or demand projections) during the process of setting their price according to the regulations. There has been no evidence of any such practices since the introduction of the minimum unit price at 50ppu. Again, as there will likely be a greater share of products falling under the minimum unit price, the more these potential impacts need to be considered.

4. Limit the choices and information available to the consumer?

A change in the minimum price for a unit of alcohol can be expected to have direct and indirect impacts on consumers. The updated price floor will lead to price changes for affected products. This means that relative prices of different alcoholic products would change as the minimum price floor would affect some products (whose price would increase), but not others (whose original price was already set above 65ppu).

It may limit consumer choice in a particular market segment as the ability to retail alcohol at prices which are cheap relative to the strength of the product will be curtailed. Those who drink most heavily will be most impacted as they are highly likely to buy these products. The volume of alcohol affected will vary with the type of alcohol.

Consumer choice may be reduced as, depending on the market response to the imposition of the updated price floor, products which previously retailed below that may disappear from the market; or they may displace those previously retailing at the 65ppu mark. Alternatively, all products may remain in the market with adjustment occurring across a wide range of price points.

In terms of pricing information, it will be possible for consumers to calculate the minimum price below which a product cannot be sold. It is estimated that the change will result in increased income to the industry via the off-trade. If firms choose to spend this on additional marketing and advertising then consumers could, potentially, have more information about the products that are available.

The evaluation of the introduction of MUP at 50ppu[184] found some qualitative evidence that MUP had constrained the promotions that could be offered by large retailers in Scotland. They had responded to this with more creative marketing of products in Scotland, including considering the use of location and space to create excitement about different products.

In the same study, smaller retailers had noted they were somewhat limited in their marketing already due to licensing regulations, so had not changed their approach particularly. In addition, the increased presence of price-marked products combined with MUP meant they were more limited on what they could offer.

For some producers, more recent changes and decisions have been made in response to Covid-19 lockdowns (e.g. selling more products in supermarkets while the on-trade was closed).

Consumers can be expected to respond to the change in price in either of two ways, either by reducing their consumption of an alcoholic product if the price increases, or by switching to alternative products (substitutes) whose relative price has decreased. The extent to which this happens will depend on consumers’ price responsiveness, i.e. the own-price elasticity (PED) and cross-price elasticities (XED) of demand, which will determine change in consumption and switching behaviour. It is not expected that minimum unit pricing will affect the ease with which customers can switch between competing products.

Own-price and cross-price elasticities:

- Own-price elasticity of demand is defined as the measure of responsiveness in the quantity demanded for a commodity as a result of a change in its own price. It is a measure of how consumers react to a change in price.

- If demand for a good is inelastic, a change in the good’s price will invoke a proportionately smaller change in demand for that good (0

- Elasticities will vary with the level of drinking, and individual’s level of income. Aggregate analysis tends to suggest that heavier drinkers have relatively more inelastic elasticities of demand for alcohol than moderate drinkers, meaning that an overall change in the price of alcohol will cause heavier drinkers to change their consumption behaviour by relatively less than moderate drinkers. However, since heavier drinkers, by definition, consume more in absolute terms, the total quantities of alcohol consumed could change more than for moderate drinkers.

- The Sheffield Model found that heavier drinkers were more responsive to price change. The model takes into account cross-price impacts which vary in a very complex way between moderate and hazardous/harmful drinkers and across the different drink and price groups of goods.

- Cross-price elasticities of demand (XED) measure the responsiveness of the demand for one good, to a change in the price of another good. If the XED between two alcohol products is high, this means that consumers would switch easily to an alternative if the price of one product increased.

As alcohol is both mind altering and addictive it might be reasonable to suggest alcohol has relatively few substitutes[185]. The PED for alcoholic beverages is therefore likely to be inelastic. Estimates of the PED will vary, however, depending on how the beverage is defined, e.g. it could reasonably be argued the most important substitute products for beer are wine and spirits. As there are relatively few substitute products, it is likely the absolute value of the own-price elasticity of beer is quite low. The same is obviously also true for wine and spirits.

The more narrowly defined the market of a product (e.g. alcohol), the greater the flexibility to switch to alternative products, i.e. the greater the elasticity. For any given brand of beer, or beer sub-market category, e.g. imported beer, there are therefore many substitute beer products. As such, it is reasonable to expect the absolute value of the PED for a specific beer brand or beer sub-market category to be relatively high.

Estimates of own price elasticities calculated and used in the most recent version of the Sheffield Model for the Scottish Government are shown in Table 72. The Sheffield Model now uses a two-step approach to price responses, in that the price affects both whether people drink or not and then if they do drink it then affects consumption level. This means there are separate participation and consumption (conditional on consumption) elasticities as shown below.

| Participation | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Beer | Cider | Wine | Spirits | RTDs | |

| Off-trade | -0.247 | -0.116 | -0.314 | -0.195 | -0.031 |

| On-trade | -0.288 | -0.086 | -0.235 | -0.176 | -0.012 |

| Conditional consumption | |||||

| Beer | Cider | Wine | Spirits | RTDs | |

| Off-trade | -1.197 | -1.136 | -0.342 | -0.221 | -0.486 |

| On-trade | -0.803 | -0.342 | -0.387 | -0.777 | -0.144 |

The interpretation of this is that a 1% increase in the price of off-trade beer would lead to 0.247% reduction in the number of people drinking off-trade beer at all, and a 1.197% reduction in the beer consumption of those who carried on drinking off-trade beer.

For comparison, examples of price-elasticities from other studies are given in Table 73.

| Study | Region | Period/type | Mean own-price elasticities | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alcohol (aggregate) | Beer | Wine | Spirits | |||

| Huang [403] ( HMRC)(2003) | UK | 1970-2002, on-trade | -0.48 | -0.75 | -1.31 | |

| 1970-2002, off-trade (beer only) | -1.03 | |||||

| Fogarty [404] (2004) | UK | Meta analysis | -0.47 | -0.72 | -0.76 | |

| Gallet [405] (2007) | International | Meta analysis | -0.54 | |||

| Wagenaar [406] (2009) | International | Meta analysis | -0.51 | -0.46 | -0.69 | -0.8 |

| Harmful drinkers only | -0.28 | |||||

| Collis, Grayson & Johal [407] ( HMRC) (2010) | UK | 2001-2006, on-trade | -0.77 | -0.46 | -1.15 | |

| 2001-2006, off-trade | -1.11 | -0.54 | -0.89 | |||

| Sousa J [408] ( HMRC) (2014) | UK | 2007-2012 on-trade | -0.34 | -0.24 | -1.25 | |

| 2007-2012 off-trade | -0.74 | -0.08 | -0.4 | |||

| Griffith, O’Connell and Kate Smith. Institute for Fiscal Studies (2017)[186] | UK | 2010-11 | -0.71 (over 35 units per week) to -2.09 (under 7 units per week) | |||

| Meng et al (2014)[187] | UK | 2001-2009 | -0.98 (off-trade) | -0.38 (off-trade) | -0.082 (off-trade) | |

| Guindon et al (2022)[188] | International | Meta analysis | -0.3 | -0.6 | -0.65 | |

Although there is little consistency in estimates, these tables show that demand for wine and beer is generally inelastic in the UK.

A change in the price of alcoholic products following a change in the level of the minimum unit price will therefore have different effects on consumption depending on these elasticities. For the more inelastic products, it can be expected that consumers will spend more if the price increases. For the relatively more elastic products, like off-trade cider, consumers would be expected to reduce their consumption in response to price increases.

The own price elasticities in Table 72 do not take into account switching behaviour. This issue is addressed by the XEDs between different alcoholic products as defined above. The values show both whether products are substitutes or complements and the strength of the relationship. The extent of switching is likely to be limited.

Contact

Email: MUP@gov.scot

There is a problem

Thanks for your feedback