Modelling impacts of free trade agreements on the Scottish economy

This report explores the modelled impact of several free trade agreements on the Scottish economy, including the UK–EU Trade and Cooperation Agreement. It considers the impact on the economy as a whole, as well as at a sectoral level, utilising Gravity modelling and Computable General Equilibrium.

Results

The following section presents estimates of the long-term impact of the modelled trade scenarios on the Scottish economy, including the impact on trade, GDP, employment, and sectoral impacts. Results are presented for the gravity modelling and Computable General Equilibrium (CGE) modelling separately followed by discussion of findings and policy implications.

All results in this section are presented as long-run impacts (over 10–15 years) relative to the baseline of continued EU membership. The modelling tools used incorporate baseline data that pre-dates the UK’s exit from the EU. This is also necessary for Scenario 2 which simulates the impact of the new UK–EU TCA itself in addition to non-EU FTAs.

Gravity

The first set of results is informed by gravity modelling and is estimated using OCEA’s gravity model of international trade.[12] This modelling is undertaken for each industry separately and estimates the direct impact of changing trade barriers on exports, imports, and output. Gravity simulations account for changes in trade with the affected partner countries as well as changes in trade with other partners.

CGE modelling results are presented later in this section and provide a more complete assessment of impacts from the CGE model, reflecting wider changes in the economy (such as reallocation of factors of production) and supply chain effects.

Scenario 1 – Non-EU FTAs

Table 3 shows how Scotland’s trade with FTA partner countries changes in response to trade liberalisation.

| Partner(s) | Export change | Import change |

|---|---|---|

| Australia | +40% (£225 million) | +43% |

| India | +42% (£125 million) | +42% |

| Switzerland | +8% (£55 million) | +15% |

| Türkiye | +8% (£15 million) | +0.5% |

| All four non-EU FTA partners | +27% | +23% |

| All international partners | +1.4% | +1.3% |

Source: SG OCEA gravity modelling and SG Export Performance Monitor.[13] Note that the monetary impact for each partner is only calculated for exports, as equivalent data is not available for imports.

The above results show substantial increases in trade with Australia and India (with both exports and imports with each country increasing by over 40% in the long run relative to the baseline of no change), with smaller increases for Switzerland and Türkiye (due to the more limited scope of those agreements). Overall international exports and imports increase a small amount (over 1%) as a result of the four non-EU FTAs, but as will be shown later, much less than the magnitude of the decrease in international trade as a result of the TCA.

The UK Government’s impact/scoping assessments of the Australia and India agreements are based on a different modelling methodology and look at UK-wide impacts, so they are not directly comparable to the results presented in this report. Nevertheless, the estimated impacts are broadly similar (see Annex A for detail).

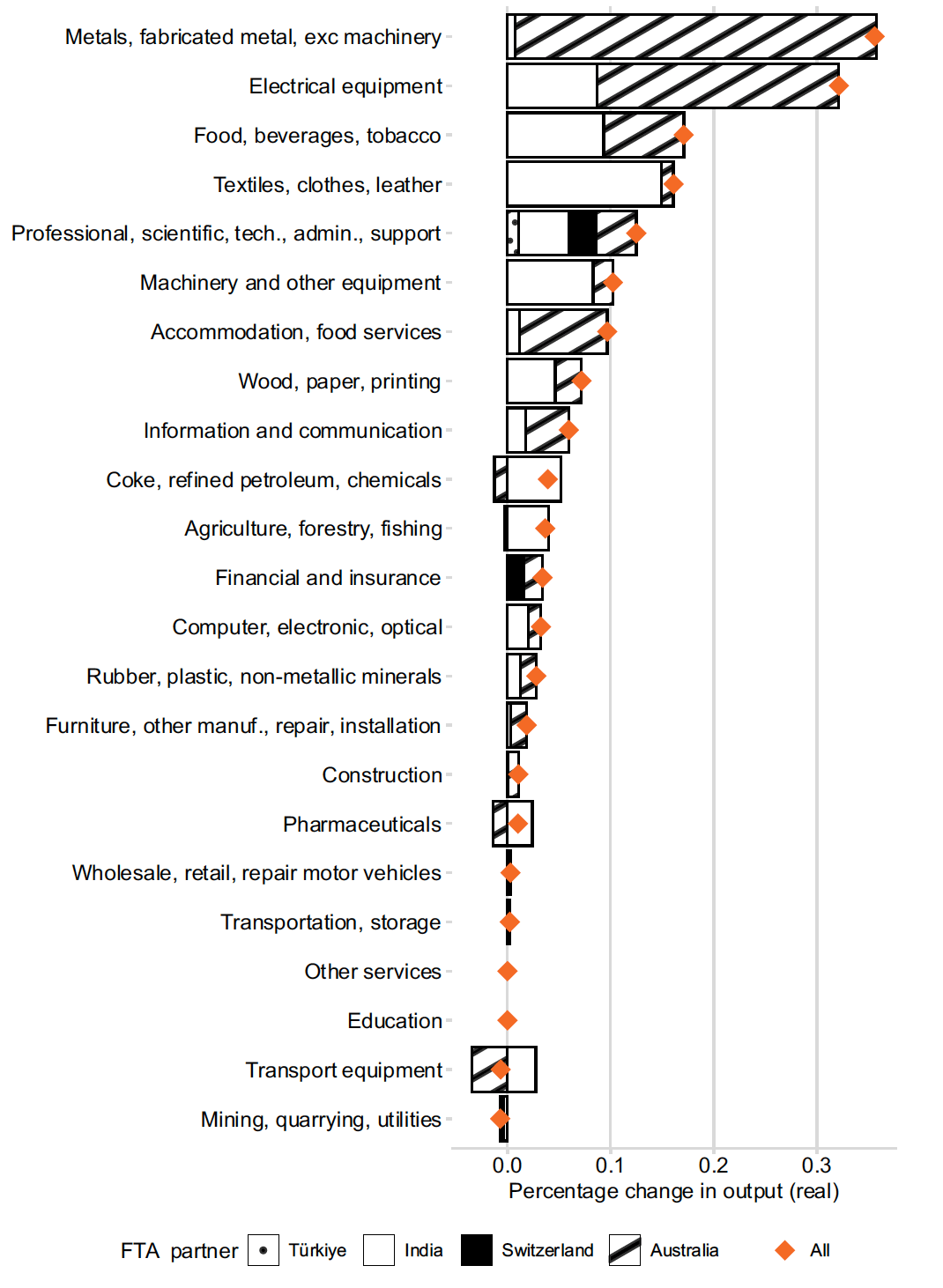

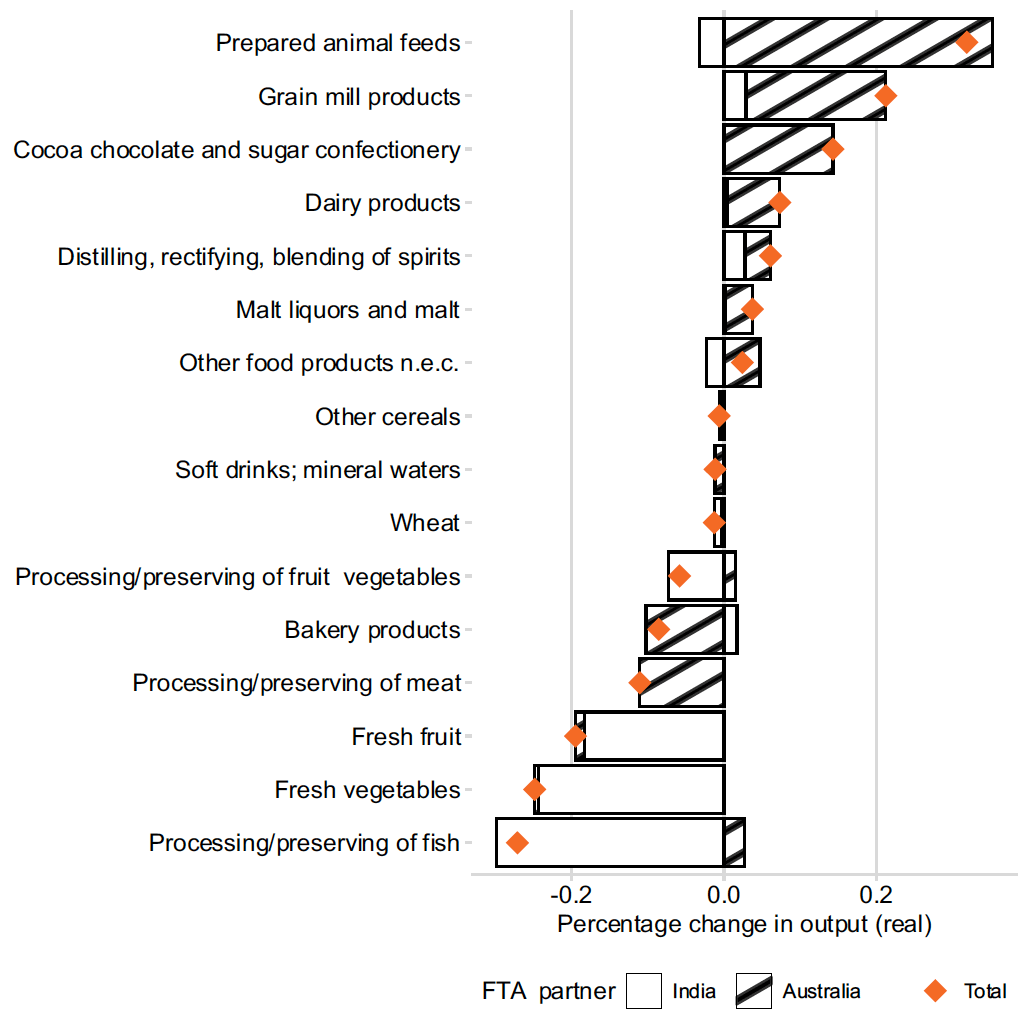

Figure 1 shows the results of our sectoral gravity simulation of Scenario 1. The impact due to each FTA is distinguishable by pattern in the stacked bar chart. All results are in real terms, meaning that they take account of any price changes resulting from the trade agreements.

The impact on Scotland’s total output, exports, and imports by sector is presented, where exports and imports include trade with all trading partners.

Some industries gain more from the FTAs than others. In terms of output, metals (+0.4%), electrical equipment (+0.3%), and food and drink (+0.2%) see the biggest increases, while transport equipment and mining, quarrying, and utilities, see very small (around 0.01%) decreases in output.

These results are informative but are at quite a high level of aggregation due to the data available for Scotland. In particular, the positive impact on Scotland’s Agrifood sector shown by these results hides a more complicated picture. More granular results are presented later in this chapter.

Metals sees a big increase in both exports and imports. For exports, this is mainly because a large share of Scotland’s exports in metals in the underlying dataset is with the non-EU FTA partners. For imports, it’s partly due to a large share of Scotland’s imports in metals being with the non-EU FTA partners, and partly due to Australia’s comparative advantage.

Accommodation and food services sees a big increase in both exports and imports in the gravity model. For exports, this might be explained by Scotland’s comparative advantage. Although not very significant in isolation, it is significantly larger than Australia and India’s comparative advantage. The trade shares in both directions are fairly high and the estimated change in trade barriers in the gravity model is relatively large which may be part of the explanation.

Professional, scientific, technical, administrative, and support services activities see a big increase in both exports and imports. This is largely explained by Scotland’s trade shares with the non-EU FTA partners being large for both imports and exports. Scotland has a big comparative advantage in this sector, which could explain why the increase in exports is larger than the increase in imports.

Electrical equipment sees a large increase in exports. The reason for this could be that, while Scotland’s comparative advantage is small, it is larger than that of Australia. Most of the gains in Electrical equipment exports are due to the UK–Australia FTA.

Source: SG OCEA gravity modelling

Scenario 2 – Non-EU FTAs and EU TCA

Table 4 shows how Scotland’s trade with partner countries and overall trade changes in response to trade liberalisation with non-EU partners and under the UK–EU TCA.

| Partner(s) | Export change | Import change |

|---|---|---|

| Australia | +36% (£200 million) | +51% |

| India | +40% (£120 million) | +49% |

| Switzerland | +7% (£60 million) | +23% |

| Türkiye | +6% (£10 million) | +7% |

| All four non-EU FTA partners | +24% | +30% |

| EU | -29% | -23% |

| All international partners | -15% | -11% |

Source: SG OCEA gravity modelling and SG Export Performance Monitor.[14] Note that the monetary impact for each partner is only calculated for exports, as equivalent data is not available for imports.

The above gravity modelling results show that the increase in trade resulting from the four non-EU FTAs is significantly outweighed by the reduction in trade with the larger EU market, leading to lower international exports and imports. The impact on trade with four non-EU partners is slightly different from the impact presented for Scenario 1 in Table 3. For example, Scenario 2 produces a larger increase in imports with four non-EU partners due to non-EU imports becoming relatively more attractive than imports from the EU which are affected by increased trade barriers.

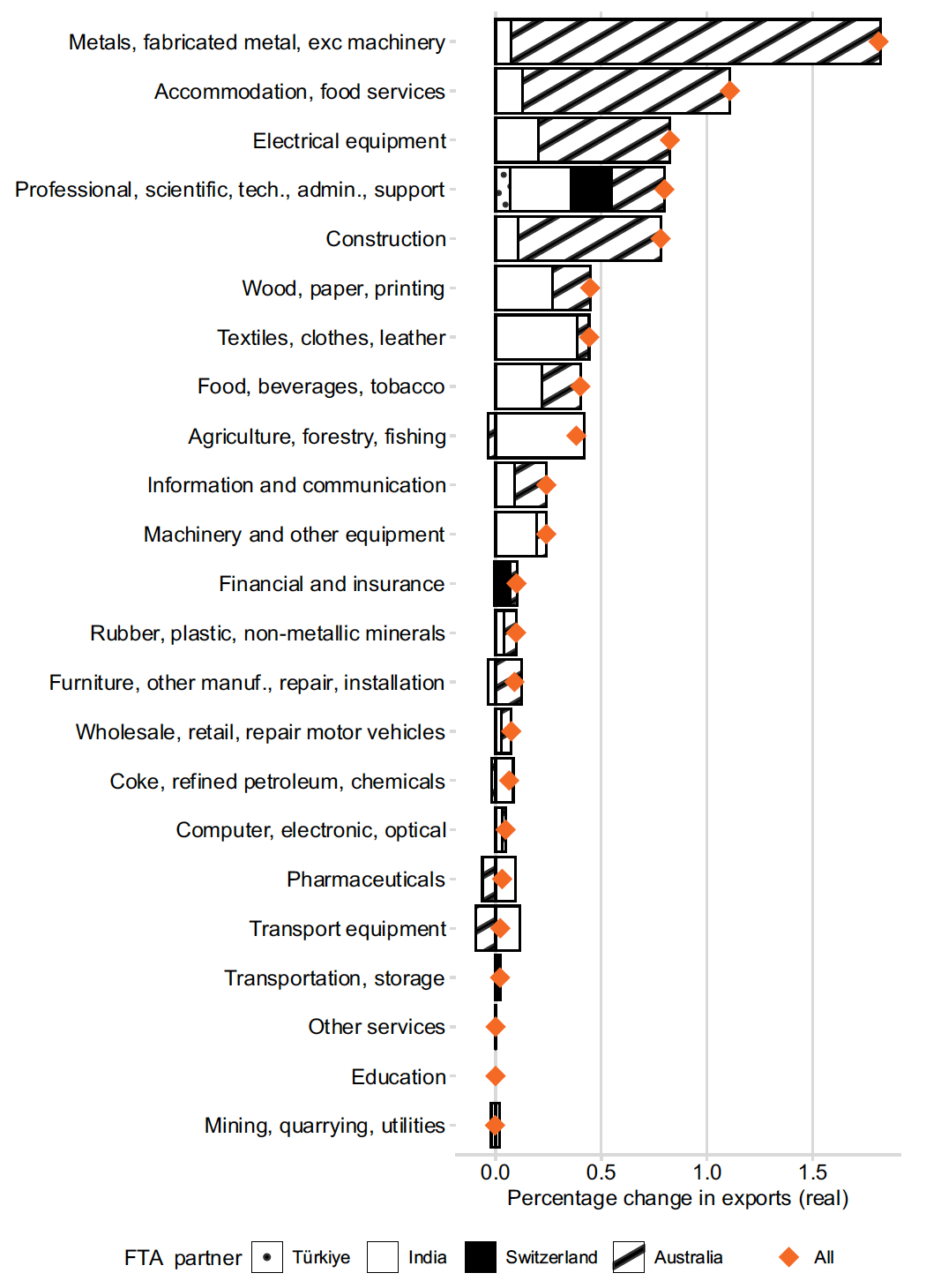

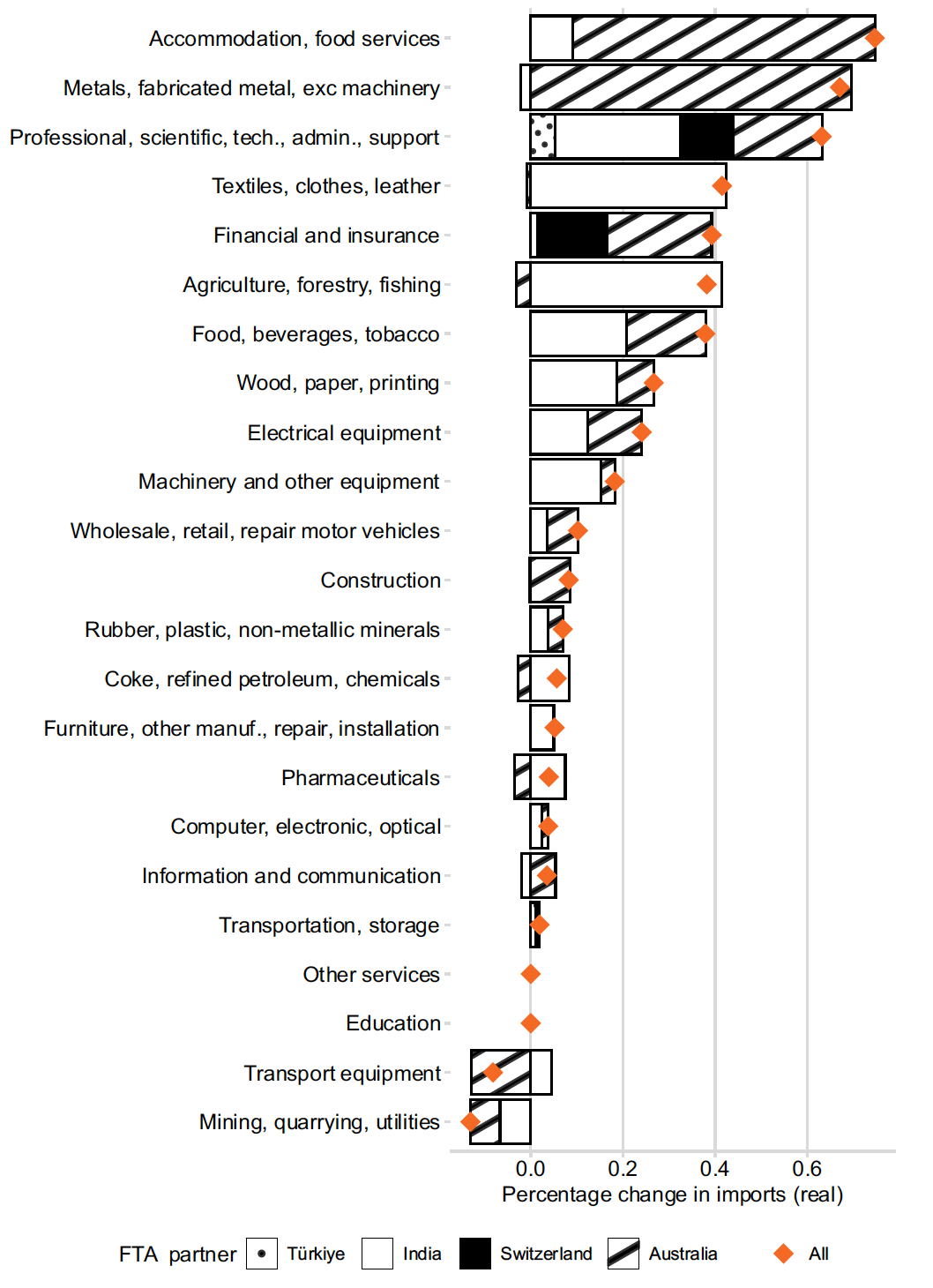

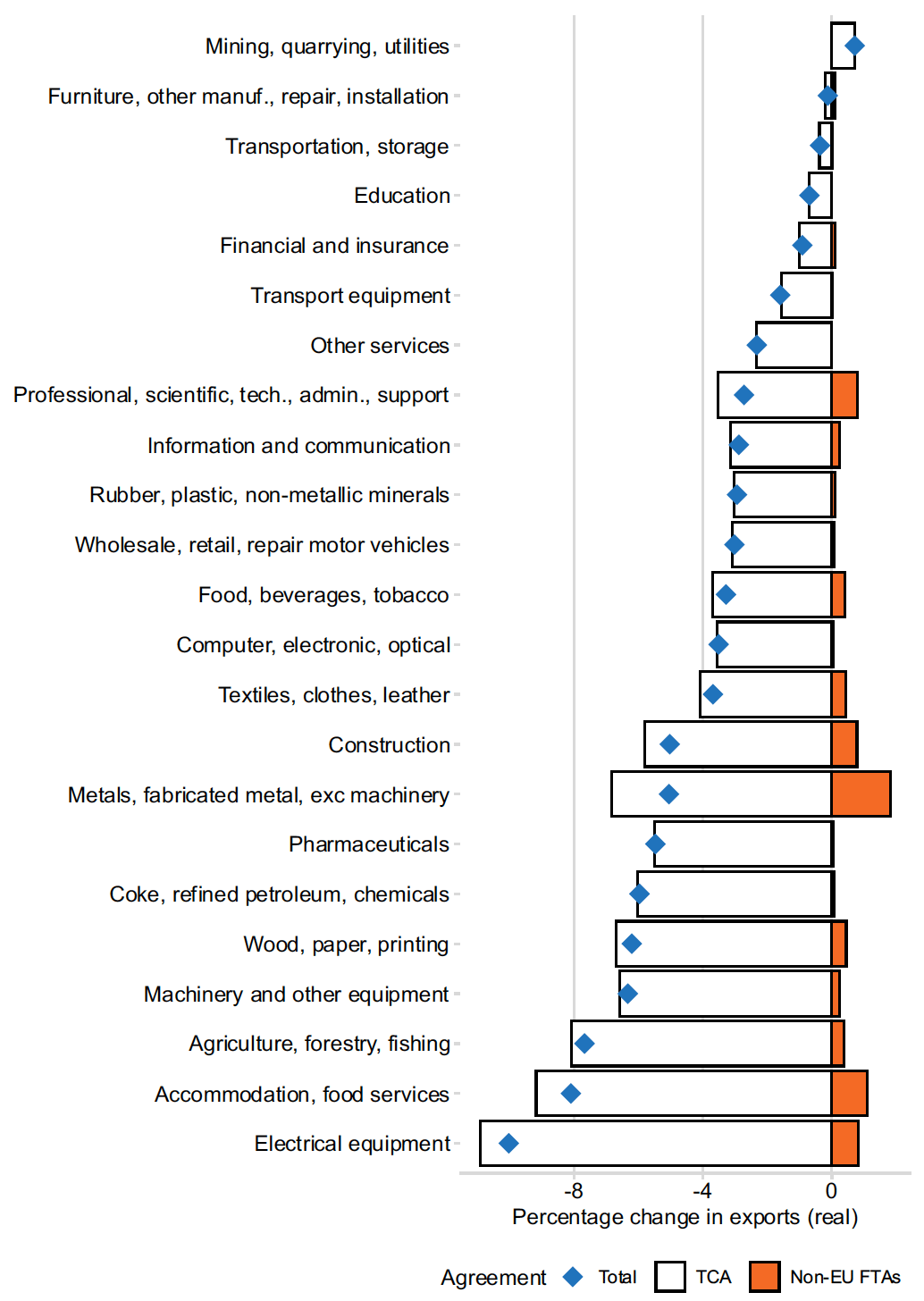

Figure 2 shows the impact on output, exports, and imports in the scenario where the UK signs all four non-EU FTAs and also the EU TCA. For readability, the effects due to the four non-EU FTAs were aggregated into one category. Just as with aggregate trade flows, the results show that reducing trade barriers with non-EU countries is insufficient to outweigh the reduction in output, exports, and imports resulting from the UK–EU TCA across most sectors.

Source: SG OCEA gravity modelling

The impact on the Agrifood sector

The Agrifood sector represents an important part of the Scottish economy. It can also be particularly sensitive to the impacts of international trade. For example, impact assessments produced by the UK Department for Business and Trade on the UK–Australia and UK–New Zealand FTAs estimated a negative impact on the Gross Value Added (GVA) of agricultural and processed food sectors. Australia has a strong comparative advantage in many areas of agriculture and it can be expected that some domestic industries could be losing out because of import competition.

Similarly, analysis produced on behalf of the Scottish Government by the Andersons Centre examining the Impact of Future UK FTA Scenarios on Scotland’s Agricultural Food and Drink Sector[15] also found some negative impacts for some sub-sectors, which are discussed below.

The Scotland-specific modelling presented above is insightful but limited by the level of industry aggregation in the data available for Scotland. The impact on the Agrifood sector as a whole can be positive as shown earlier but the impact can vary greatly across different subsectors or businesses. The positive aggregate result is in part driven by the inclusion of Drink in the total in the data available. The Scotch whisky sector is generally expected to gain from non-EU FTAs, with the current Indian tariff on whisky set at 150%.

Given the greater significance of the Agrifood sector in the Scottish economy than in the UK as a whole, and particularly in remote and island communities, it is important to understand these impacts in greater detail.

To provide a more comprehensive assessment for the sector, the next results draw from UK level data and modelling. UK data in the International Trade and Production Database for Estimation (ITPD-E)[16] provides a much more granular breakdown of these sectors but has the limitation of only allowing to model trade at the UK level. This may not be a problematic limitation – it is expected that findings at this sub-sectoral level could be very similar for Scotland.

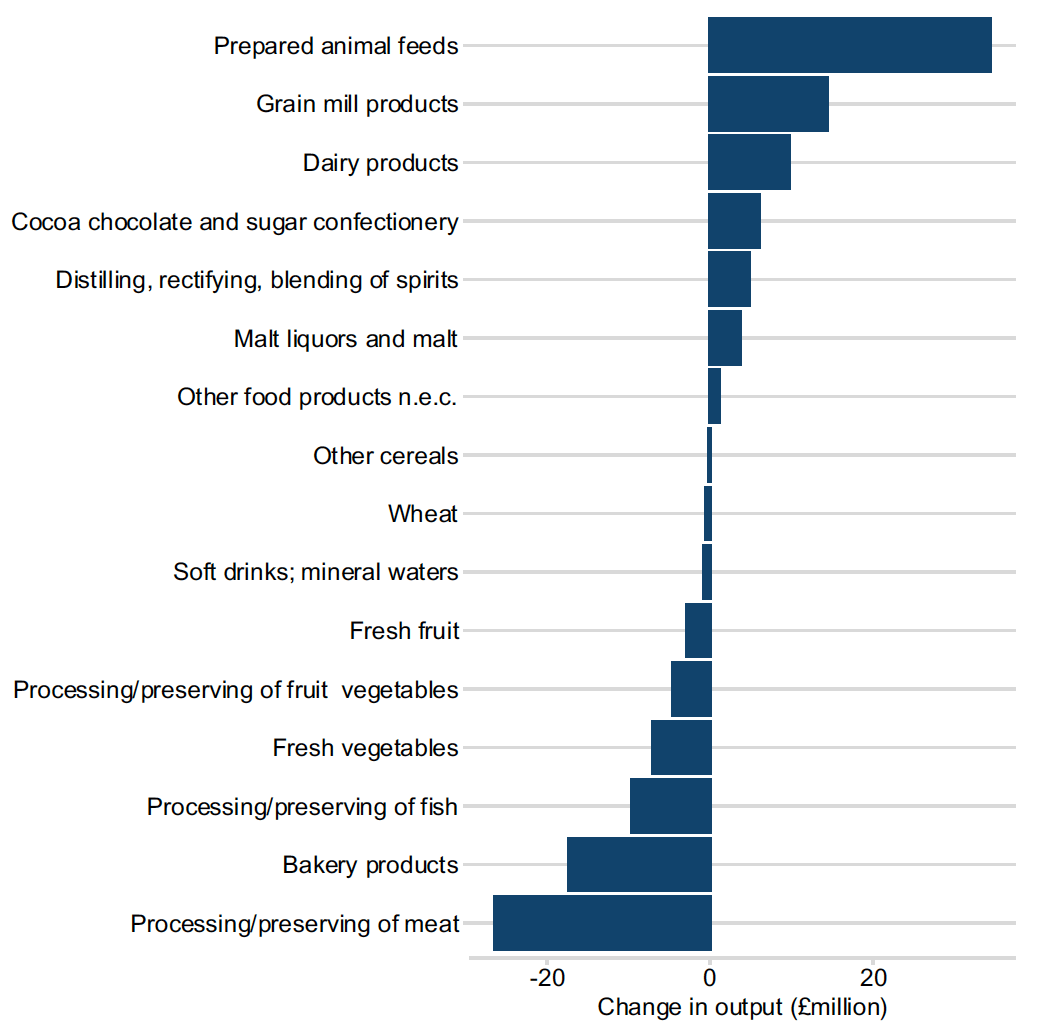

Figure 3 shows the results of our gravity simulation for agriculture and food sectors using granular ITPD-E data. The more granular breakdown shows that the impact of the FTAs are more complicated than simply expanding or harming the agri-food sector, with some industries experiencing an increase in real output and others seeing a decrease.

We present only a subset of all agri-food sub-sectors in the ITPD-E dataset. The ones we omit are those with very small UK production, as these are less important to the wider picture.

Cash terms impacts in millions GBP[17]

Source: SG OCEA gravity modelling

The industries experiencing the largest increase in real output are Prepared animal feeds (+0.3%, +£34m), Grain mill products (+0.2%, +£14m), and Dairy products (+0.07%, +£10m). The industries experiencing the largest decrease in real output are Processing/preserving of meat (-0.1%, -£26m), Bakery products (‑0.09%, ‑£17m), and Processing/preserving of fish (-0.3%, -£10m). In addition, it should be noted that above charts are likely to underestimate the impact on the Scottish whisky sector as the modelling approach does not directly account for reductions in tariffs on whisky (currently at 150% in India) due to the lack of disaggregated data.

It is possible to compare the agrifood results presented above with previous work. A 2023 study by The Andersons Centre on behalf of the Scottish Government[18] analysed a high liberalisation and a low liberalisation scenario, and found that an FTA with Australia could result in UK GVA decreasing by 2.8% and 2.4% for Beef and Sheepmeat respectively in the low liberalisation scenario, and 6.7% and 3.6% in the high liberalisation scenario. Direct comparison may be misleading because above results are for total output, and the results of the Andersons study are GVA and informed by a different model, but the Andersons study does appear to show larger impacts than this analysis.

A 2022 impact assessment by the Department for International Trade in the UK Government[19] also analysed the impact of the FTA with Australia. It estimated reduction in gross output of around 3% and 5% for Beef and Sheepmeat respectively. Although these different analyses used different approaches, and the fundamentally uncertain nature of modelling means different models could produce different results, there may be an indication that this analysis underestimates the impact on meat production.

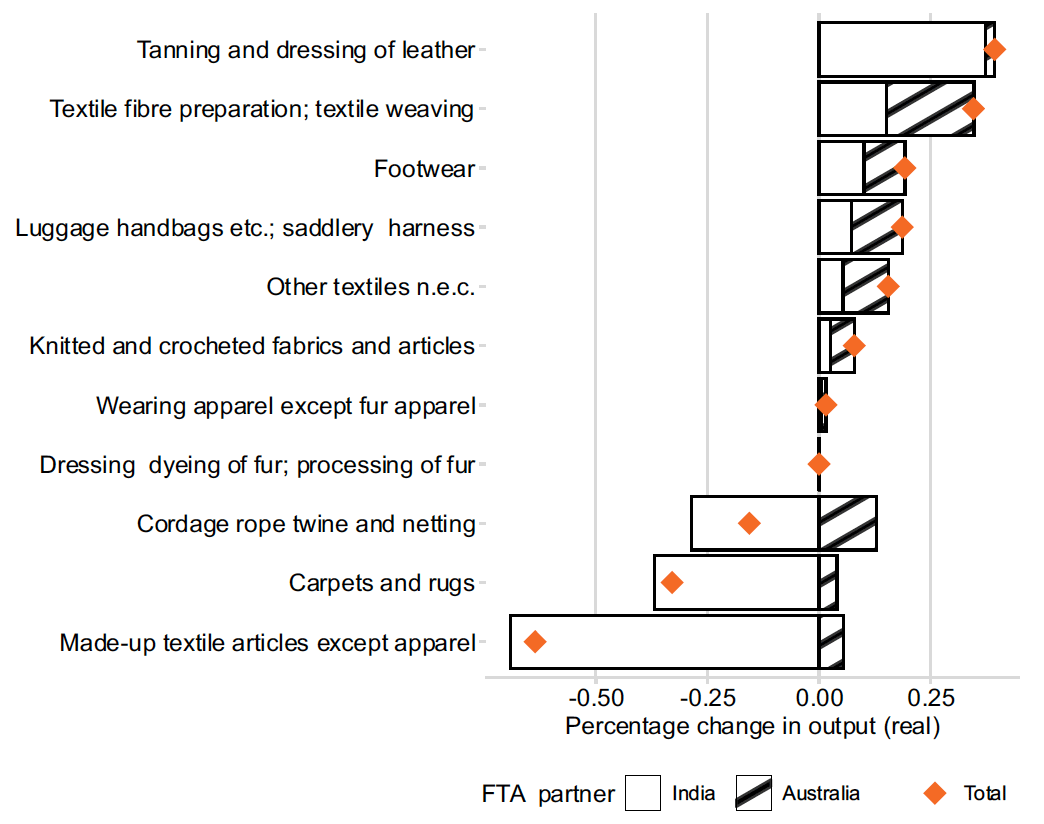

The impact on the Textiles sector

Another area of interest, due to India’s strong comparative advantage, is Textiles, Clothes, and Leather. Textiles and Apparel were estimated to see a reduction in GVA in the UK Government analysis of UK–India FTA, with the reduction estimated to be larger with a deeper agreement. In the gravity model for Scotland these industries are aggregated to a single sector due to data limitations, but in the UK gravity model they are represented by 11 industries.

Figure 4 below shows the results of our gravity simulation at the UK level for the industries covered by Textiles, Clothes, and Leather. As with Agri-food, it can be seen that some industries’ output increases, while that of others decreases.

The industries experiencing the largest increase in real output are Tanning and dressing of leather (+0.4%), Textile preparation and weaving (+0.3%), and Footwear (+0.2%). The industries experiencing the largest decrease in real output are Made up textile articles except apparel (-0.6%), Carpets and rugs (-0.3%), and Cordage, rope, twine, and netting (-0.2%).

Source: SG OCEA gravity modelling

Computable General Equilibrium

This section presents the results from CGE modelling and provides a more complete assessment of the combined impact of FTAs with four countries and the UK–EU TCA on the Scottish economy, accounting for wider feedback effects such as reallocation of factors of production and supply chain effects.

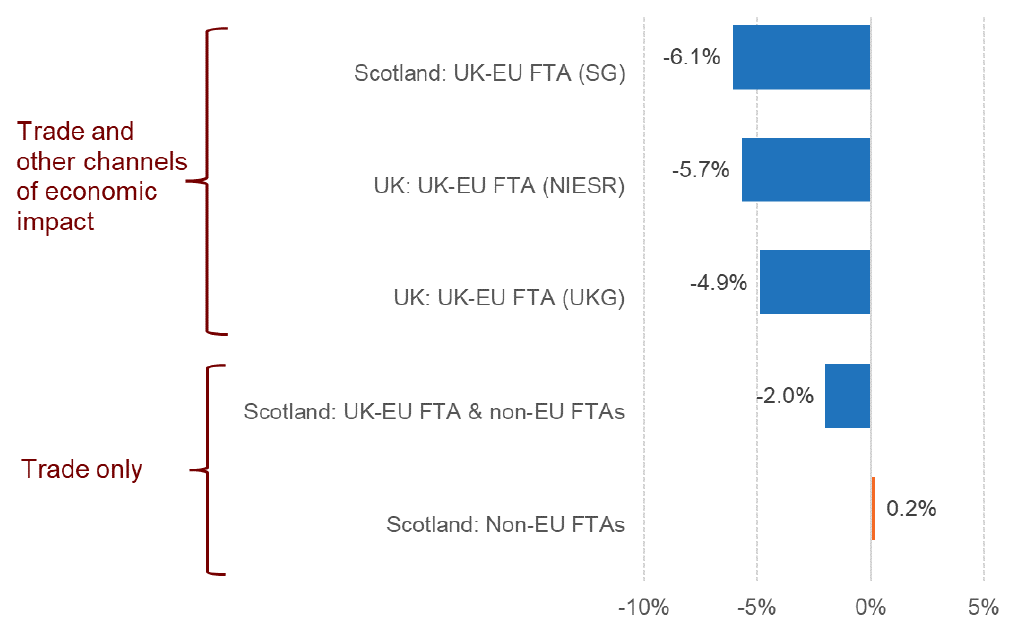

As before, all results in this section are presented as long-run impacts (over 10–15 years) relative to the baseline of continued EU membership. Figure 5 shows the estimated impact of two scenarios on Scotland’s GDP and trade in the long run in this analysis alongside other estimates of the TCA impact. The four non-EU FTAs alone (Scenario 1) are estimated to increase Scotland’s GDP by 0.2% in the long run whereas under the UK–EU TCA and with four non-EU FTAs implemented (Scenario 2) GDP is estimated to be at least 2% lower compared to the baseline of continued EU membership. A sensitivity analysis (presented in Annex E) shows that for Scenario 2 the impact on GDP ranges from -1.4% to -2.7%, when changing some of the parameters underpinning central estimates presented in this report.

Sources: Trade only impacts – this report / SG OCEA CGE modelling (2025); Trade and other channels of economic impact – UK Government (2018);[20] NIESR (2023)[21]; SG OCEA SGGEM modelling (2018)[22]

Scenario 1 and Scenario 2 in this report only reflect changes in trade due to increased barriers whereas other estimates of TCA impacts by the UK Government (2018), the National Institute of Social and Economic Research (NIESR, 2023), and earlier Scottish Government’s macroeconomic modelling (2018) accounted for other channels of impacts such as any changes in productivity or investment as a result of the UK’s exit from the EU. These other channels of impact can have significant economic effects as shown in Figure 5. For example, recent modelling by NIESR estimates that the UK’s GDP could be 5.7% lower in the long run than if the UK had remained in the EU.

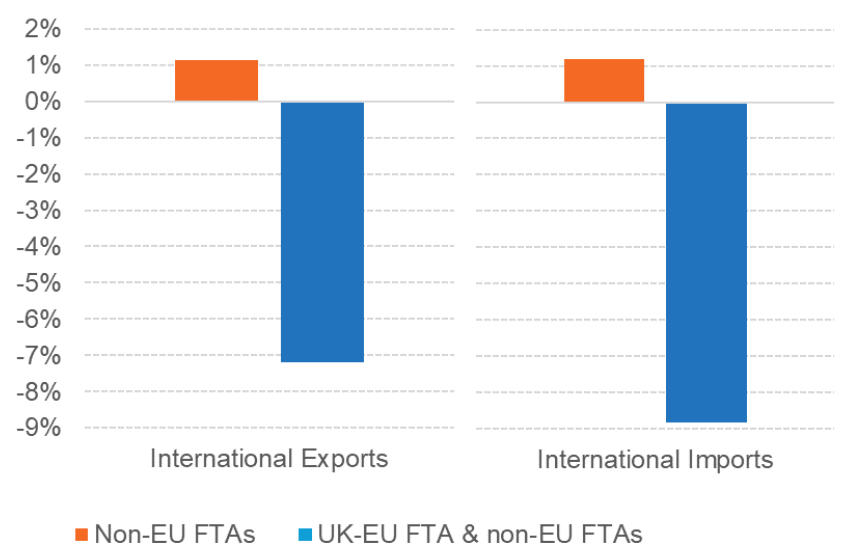

Figure 6 shows that under Scenario 1, international exports and imports could increase by 1.1% and 1.2% whereas under Scenario 2, international exports are estimated to be 7.2% lower and international imports 8.8% lower. The following sections explore sectoral impacts of both scenarios.

Source: SG OCEA CGE modelling

Scenario 1 – Non-EU FTAs

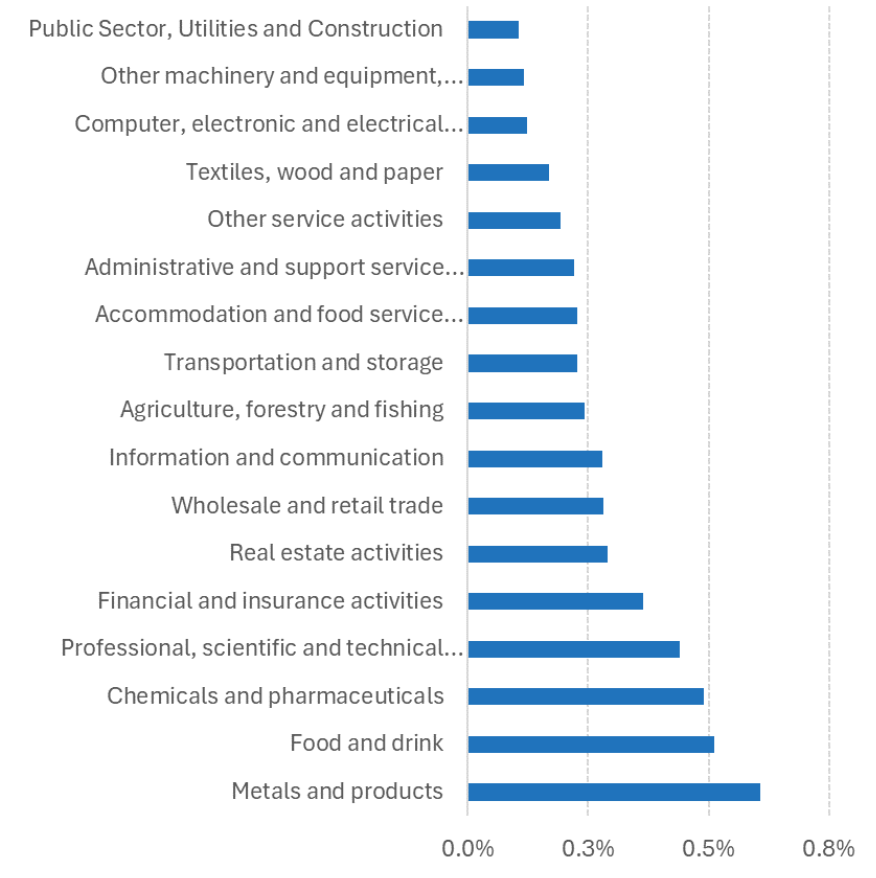

Figure 7 shows the impact of the four non-EU FTAs on sectoral employment in the Scottish economy. As a result of trade liberalisation, the level of employment increases across all industries, with the largest increase observed in Metals and products, where employment increases by 0.6% relative to the baseline, followed by Food and Drink sector with 0.5% increase.

Source: SG OCEA CGE modelling

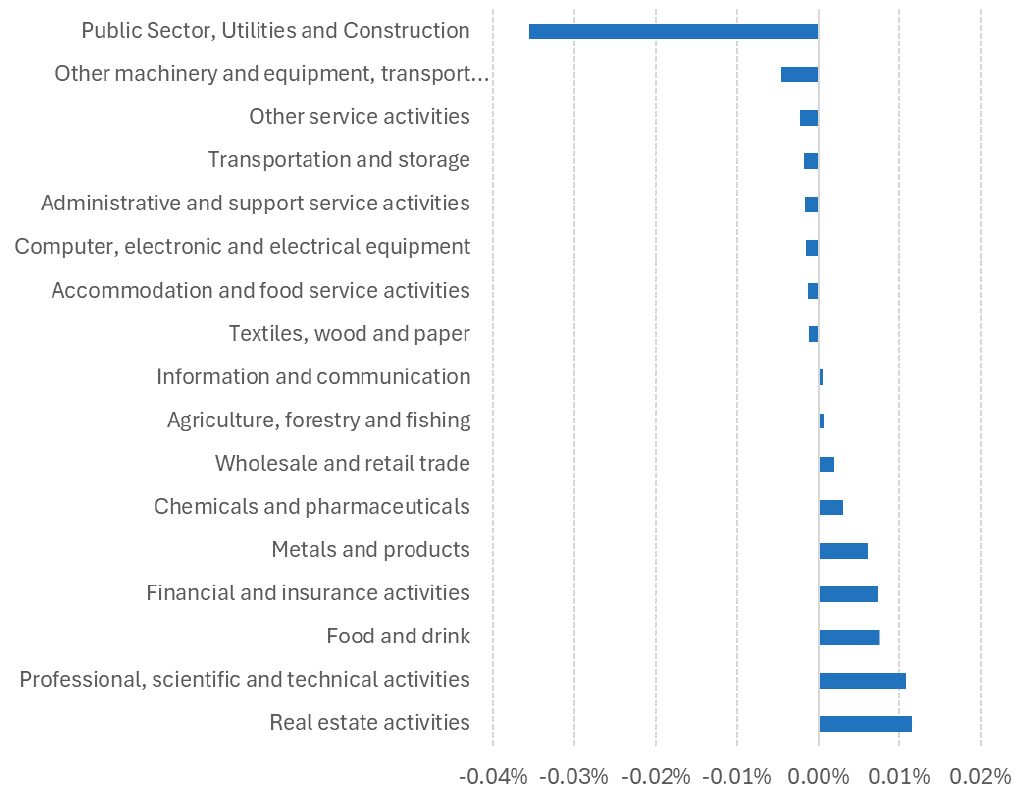

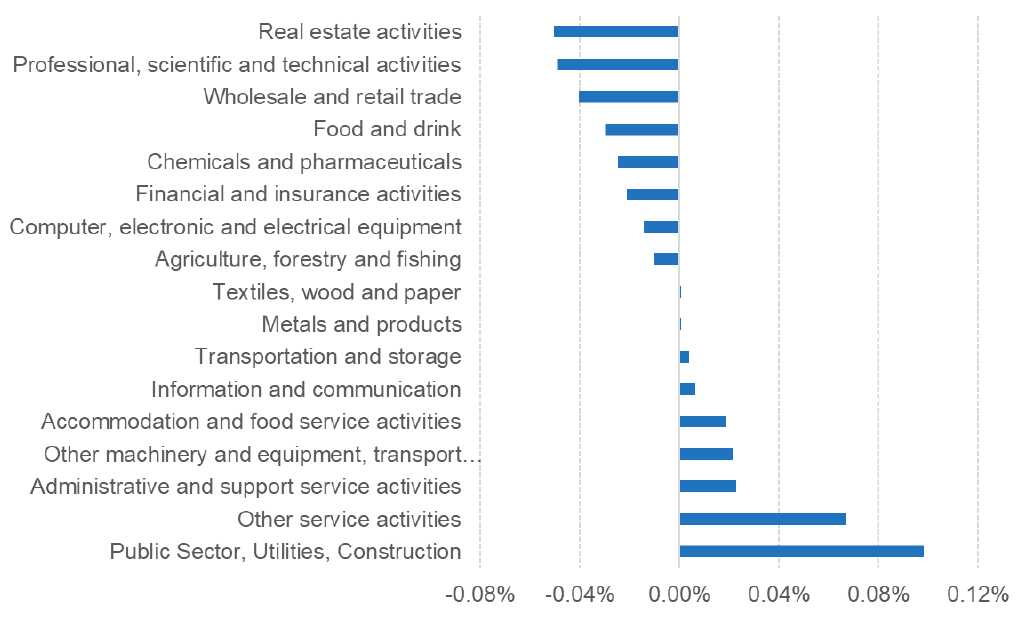

Whilst the level of employment is slightly higher across all sectors of the economy, Figure 8 shows a small decrease in the contribution of non-tradeable sectors as a share of total GVA. The share of total GVA for Public Sector, Utilities and Construction falls by 0.036 percentage points.

In contrast, some tradeable sectors – such as Professional Services, Food and Drink, Financial Services, and Metals – experience a very small increase (just over 0.01 percentage points) in their share of total GVA. This is not surprising: tradeable sectors become relatively more important in the economy due to the removal of trade barriers, which drives reallocation of resources towards those sectors and changes slightly the structure of the economy. For illustration, this means that whilst in the baseline Public Sector, Utilities and Construction accounted for around 35.13% of total GVA in the modelled economy, under this scenario the share drops to 35.10%. These changes are relatively small.

Source: SG OCEA CGE modelling

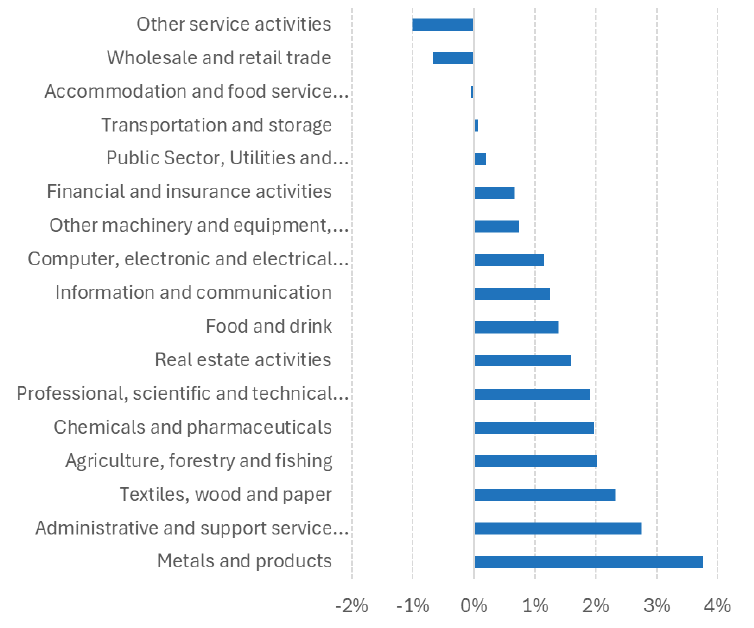

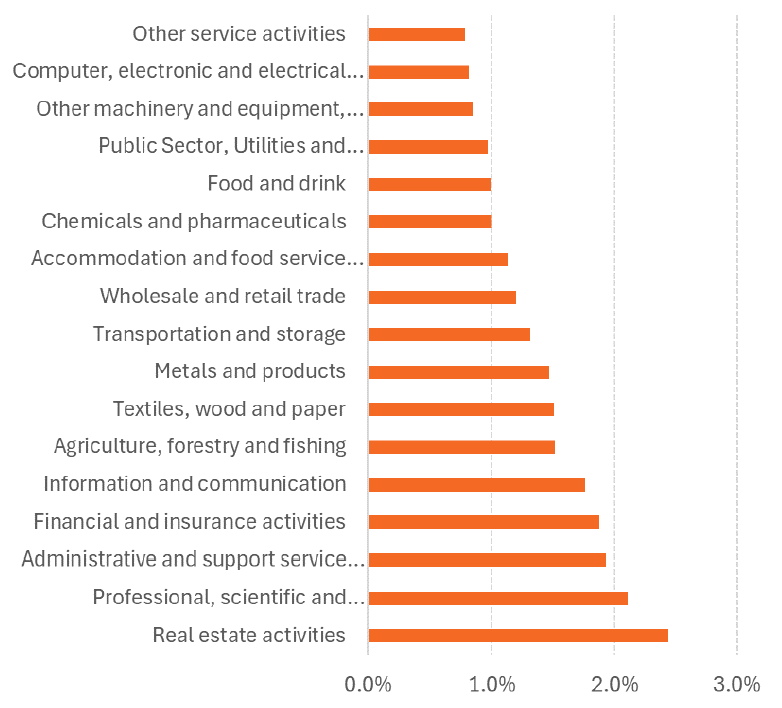

Figure 9 below shows estimated changes in international exports from the four non-EU FTAs. The largest increase in exports is estimated for Metals (+3.8%), followed by Administrative and Support Services (2.8%), and Textiles (+2.3%).

Figure 10 shows the estimated effect on international imports from the four non-EU FTAs. The largest increases are estimated across a number of services sectors, such as Real estate (+2.4%), followed by Professional, scientific and technical (+2.1%), and Administrative and support services (+1.9%).

Source: SG OCEA CGE modelling

Scenario 2 – Non-EU FTAs and TCA

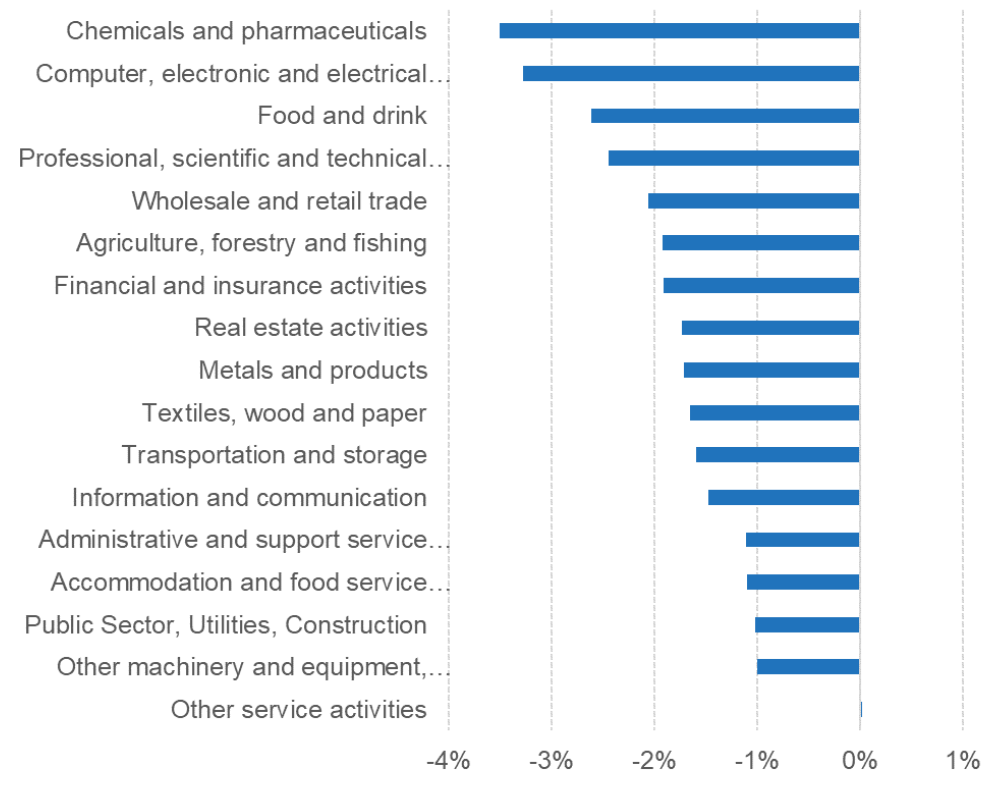

Figure 11 shows the combined impact of UK–EU TCA and four non-EU FTAs on sectoral employment in the Scottish economy. The level of employment decreases across all industries, with the largest decrease observed in Chemicals and Pharmaceuticals where employment is 3.5% lower than in the baseline, followed by Computer & electronics (-3.3%) Food and Drink (-2.6%), and Professional Services (-2.4%). The estimated impact on employment is only very marginally positive, if not negligible, in Other service activities.

Source: SG OCEA CGE modelling

Figure 12 shows the extent of the restructuring in the Scottish economy – measured by a share of GVA – in response to a much bigger change such as the UK–EU TCA and liberalisation with non-EU countries. As the economy is less open to trade, there is a small increase in the GVA of non-tradeable sectors as a share of total GVA. The GVA share of Public Sector, Utilities and Construction increases by 0.10 percentage points relative to the baseline. In contrast, some tradeable sectors – such as Professional Services, Wholesale and Retail, Food and Drink, Chemicals, and Financial Services – experience a very small decrease in their share of total GVA. Overall, Figure 12 suggests some compositional changes in the economy as tradeable sectors become relatively less important in the economy with the increased trade frictions under TCA outweighing any reduced barriers with non-EU partners.

Source: SG OCEA CGE modelling

Table 5 shows estimated changes in output of each sector, with the largest percentage reductions estimated for Chemicals and pharmaceuticals (-9.1% or £424 million), Computer, electronic and electrical equipment (-7.7% or £296 million), Textiles, wood and paper (-5.9% or £289 million), Metals (-5.9% or £240 million), and Agrifood (-4.9% or £827 million). The sectors impacted are somewhat similar to the results from the gravity simulations covered earlier in this report but unlike the earlier results, these estimates account for any supply chain impacts and wider economic effects, often amplifying the impact of the initial trade shock.

| Sector | % change | Change in £m, based on 2019 output data |

|---|---|---|

| Chemicals and pharmaceuticals | -9.1 | -£424m |

| Computer, electronic and electrical equipment | -7.7 | -£296m |

| Textiles, wood and paper | -5.9 | -£289m |

| Metals and products | -5.9 | -£240m |

| Food and drink | -4.9 | -£540m |

| Agriculture, forestry and fishing | -4.8 | -£287m |

| Other machinery and equipment, transport equipment | -2.8 | -£246m |

| Professional, scientific and technical activities | -2.1 | -£325m |

| Other service activities | -1.9 | -£589m |

| Real estate activities | -1.9 | -£397m |

| Administrative and support service activities | -1.6 | -£176m |

| Information and communication | -1.4 | -£339m |

| Financial and insurance activities | -1.4 | -£122m |

| Transportation and storage | -1.3 | -£156m |

| Public Sector, Utilities, Construction | -0.7 | -£490m |

| Wholesale and retail trade | -0.6 | -£140m |

| Accommodation and food service activities | -0.5 | -£42m |

Source: SG OCEA CGE modelling; Scottish Government Supply and Use Tables 2019

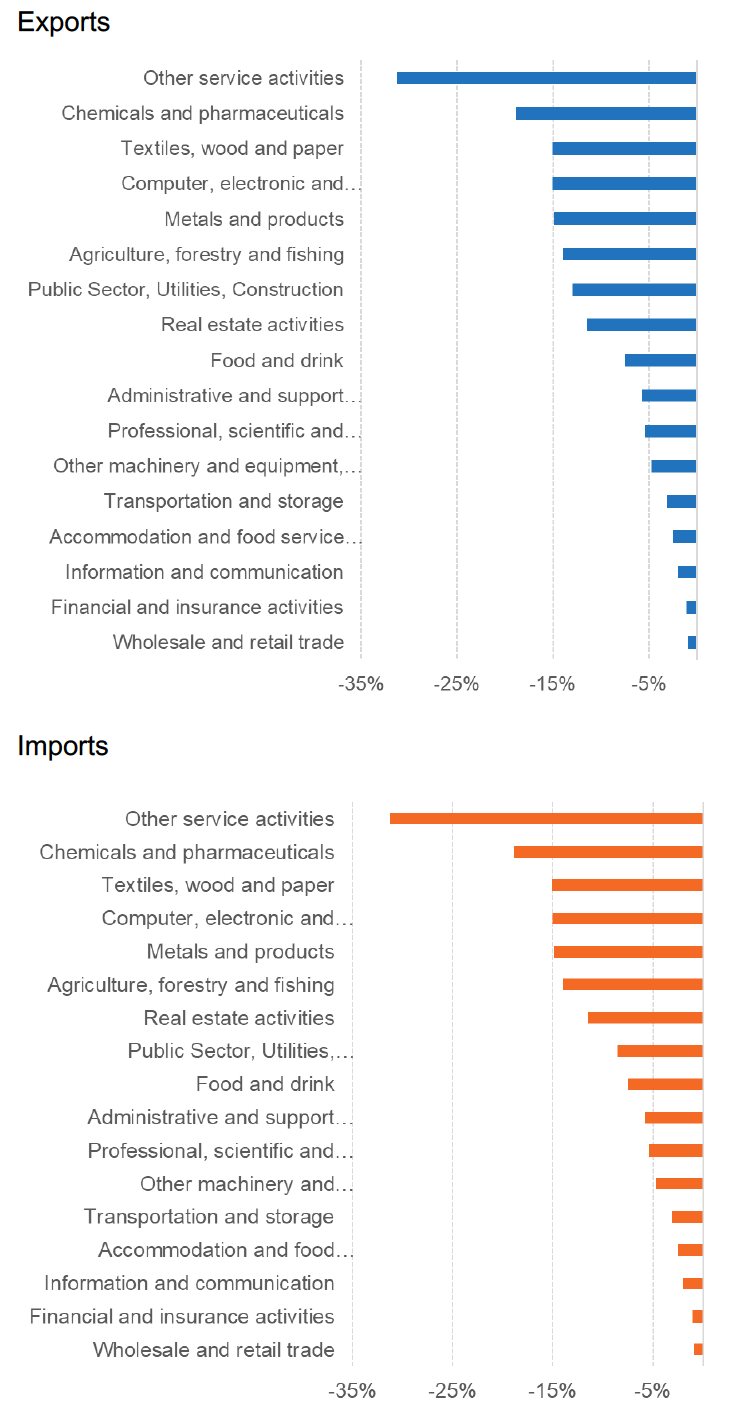

Figure 13 shows the combined impact of UK–EU TCA and four non-EU FTAs on international exports, with all sectors experiencing a decrease relative to the baseline. The largest decrease is estimated for Other services activities (-31.2%), followed by Chemicals and Pharmaceuticals (-18.8%), and Textiles (-15.1%). Similarly, international imports across all sectors are also estimated to decrease in the long run, with the largest decreases observed in the same sectors as for exports.

Source: SG OCEA CGE modelling

Limitations

This analysis aims to estimate the long-term impact of trade policy changes using a range of established modelling frameworks. Any economic modelling is inherently uncertain and driven by assumptions. Assumptions underpinning the gravity model and CGE model are covered in Annex B and D.

There are underlying data limitations which affect the modelling. The main international trade dataset that is widely used for gravity modelling, ITPD-E, has some problems with missing data. Our Scottish version, based on ITPD-E, mitigates this to some extent by using more aggregated sectoral data (due to lack of availability of granular trade data for Scotland).

However, this lack of granularity in Scottish data, both for the gravity model and the CGE model, limits the detail available in the modelling outputs. It also makes it difficult to undertake any detailed analysis of any changes in tariffs and non-tariffs barriers for the scenarios which is typically done with product-level data.

The other key data limitation is that the baseline year for the data used in the models is 2018 for the gravity model and 2013 for the two-region CGE model, reflecting the latest available Social Accounting Matrix that incorporates both Scotland and the rest of the UK. Whilst it is typical for economic models to use lagged data for the baseline year there have been changes in the economy over the period that may have a bearing on the results of simulations. That said, the structure of the economy – in terms of sectoral composition and importance of tradeable sectors – has not necessarily changed substantially which provides a level of confidence in the simulation results. The lagged nature of the model inputs is also the reason why all monetary figures are informed by the latest statistics on international exports, imports, and employment.

One of the key assumptions driving the results of this analysis are assumed changes in trade costs due to changes in trading relationships. This analysis assumes that changes in trade costs with each partner country would reflect an impact of an average trade deal as estimated in a sectoral gravity model. The estimated impact of an average trade deal reflects the impact of both reductions in tariffs and other trade costs, and non-tariff barriers. This means that trade costs estimates are highly uncertain and may not reflect the actual changes in trade costs. On the other hand, the approach taken has a benefit of being simple and transparent and is also widely used in the literature.[23]

In addition, the estimated impact of an average trade deal relies on a sample of data and changes in trading relationships between countries covering 2003–2018 in line with the approach taken by a study that estimates sectoral gravity model using similar data.[24] This estimate may not be reflective of changes in trade that may take place under future trading agreements. It also possible that the main specification omits important factors such as any changes in relative trends between international and domestic trade, the pace of globalisation and other factors. The literature in this space is still evolving and there is no established best practice approach to estimating the impact of trade agreements.

Moreover, it is also assumed that the impact of the UK–EU TCA relative to the continued EU membership can be also captured by changes in trade costs for an average trade deal. It is likely that the negative impact of replacing the full EU membership with the UK–EU TCA could be larger in magnitude than the impact of an average trade deal due to the depth of the economic relationship between the UK and the EU compared to the average trade agreement and wider channels of economic impact.

It is possible to account for larger changes in trade barriers in a gravity model specification and that could mean that the UK–EU TCA could represent an even larger negative shock for the economy. At the same time, it would not alter substantially one of the key findings of this analysis – the cumulative impact of trade liberalisation with a number of non-EU partners represents a much smaller economic shock than changes in the economic relationship with the EU.

Taken together, the uncertainty around changes in trade costs is explored through further sensitivity analysis and robustness checks. As part of these checks, additional simulations are undertaken using lower and upper estimates of changes in trade costs or varying value of key parameters such as trade elasticity to develop ranges for the estimated impacts in addition to the reported central estimates. These are covered in more detail in Annex E.

In this report we present estimated impacts from both the gravity model and the CGE model. The methodological differences between the two approaches, and their individual limitations, can lead to differences in results. Using both approaches in conjunction allows us to mitigate their individual limitations. The fact that the models often yield broadly similar findings despite their methodological differences gives confidence in the robustness of the results.

A limitation of the sectoral gravity modelling is that the relationship between different sectors is not taken into account. In the real economy, a change in prices in one sector can affect prices in another sector, due to changes in the cost of inputs or substitution effects. The gravity model treats each sector separately, ignoring any such effects. This is one reason for combining the gravity analysis with the CGE model, which has input–output linkages between sectors built in.

The CGE model used in this report, while it does include trade, is not primarily designed as a trade model, and it treats the rest of the world as completely exogenous. This means that third country effects are not included. This is not likely to be a significant issue, due to the small scale of the Scottish economy and the scenarios considered. This is also an aspect that the gravity model is designed to include.

It should be noted that the differential impacts analysis presented in this report uses aggregated data and relies on sectoral averages to show how different types of workers or different geographies in Scotland could be impacted by the scenarios. Data limitations mean that any impacts are highly illustrative and may not reflect the true experiences of workers and communities across Scotland.

Furthermore, this analysis only provides an indication of magnitude and direction of the potential impact on the economy under scenarios analysed. It does not provide a forecast of the future path of the economy but shows what the impact may be relative to the baseline under a specific set of scenario assumptions. It also does not account for any other changes and economic policy changes that may take place and transform the economy, nor does it consider any potential future changes in the global economy, including any potential changes in demand, trade, and technological progress.

Contact

Email: EUEA-SG@gov.scot

There is a problem

Thanks for your feedback