Modelling impacts of free trade agreements on the Scottish economy

This report explores the modelled impact of several free trade agreements on the Scottish economy, including the UK–EU Trade and Cooperation Agreement. It considers the impact on the economy as a whole, as well as at a sectoral level, utilising Gravity modelling and Computable General Equilibrium.

Annex

A. UK Government analysis for Australia and India FTAs

| Trading partner | Export change | Import change |

|---|---|---|

| Australia | +44.2% | +66.1% |

| All international partners | +0.43% | +0.36% |

Source: Impact assessment of the Free Trade Agreement between the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland and Australia (publishing.service.gov.uk) See page 66, Table 5.

| Trading partner | Export change | Import change |

|---|---|---|

| India (Scenario 1) | +49.5% | +30.7% |

| All international partners (Scenario 1) | +0.5% | +0.38% |

| India (Scenario 2) | +94.6% | +63.7% |

| All international partners (Scenario 2) | +1.1% | +0.77% |

Source: UK–India Free Trade Agreement – The UK's Strategic Approach (publishing.service.gov.uk) See page 55, Table 2. Scenarios 1 and 2 represent moderate and higher degrees of tariff liberalisation respectively, defined on page 54.

Compared to modelling results in Tables 3 and 4 of this report, the impact on exports to Australia is similar, but UK modelling finds larger impact on imports. The modelling results for India presented in this analysis are broadly similar to the UK results under a moderate degree of tariff liberalisation. It would not be reasonable to expect the results to be exactly the same, as a different modelling methodology was deployed in this report and there could be underlying differences between the Scottish and UK economies.

It is also important to note that the “all international” export and import changes are based on just considering one FTA at a time, while SG results presented in Tables 3 and 4 are based on all scenarios cumulatively.

B. Gravity model

Estimation and Simulation

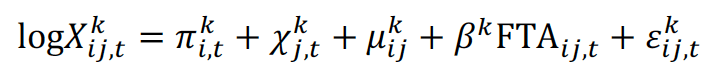

The following equation to specify the gravity model is used.

Where:

is the trade flows from country i to country j in year t for industry sector k

is the trade flows from country i to country j in year t for industry sector k is the exporter–year fixed effect

is the exporter–year fixed effect is the importer–year fixed effect

is the importer–year fixed effect- FTAij,t is a dummy variable recording whether countries i and j have a free trade agreement in year t

is the coefficient that determines the magnitude of the effect of a free trade agreement on trade flows after controlling for the fixed effects

is the coefficient that determines the magnitude of the effect of a free trade agreement on trade flows after controlling for the fixed effects is a stochastic error term

is a stochastic error term

Trade data from the Scottish International Bilateral Trade Dataset (SIBTD) and International Trade and Production Database for Estimation (ITPD-E)[30] to obtain  , data from the Dynamic Gravity Dataset to obtain FTAij,t, and use Poisson Pseudo-Maximum Likelihood (PPML) estimation with fixed effects to estimate

, data from the Dynamic Gravity Dataset to obtain FTAij,t, and use Poisson Pseudo-Maximum Likelihood (PPML) estimation with fixed effects to estimate  [31]. This model is applied to each industry separately in SIBTD and ITPD-E, using data from 2003 to 2018. In addition, partial estimates in instances where the model does not converge or produce economically meaningful results are also supplemented with values from Borchert et al. (2020) which runs a slightly different PPML specification for the 170 industries in the International Trade and Production Database for Estimation (ITPD-E).

[31]. This model is applied to each industry separately in SIBTD and ITPD-E, using data from 2003 to 2018. In addition, partial estimates in instances where the model does not converge or produce economically meaningful results are also supplemented with values from Borchert et al. (2020) which runs a slightly different PPML specification for the 170 industries in the International Trade and Production Database for Estimation (ITPD-E).

For simulation, the ge_gravity function in the GEGravity R package[32] is used with the baseline year of 2018 and using a trade elasticity parameter of 4.

Data

For Scotland-specific analysis a new dataset called the Scottish International Bilateral Trade Dataset (SIBTD) is used. This dataset is based in the International Trade and Production Database for Estimation (ITPD-E), which is a widely used dataset for gravity estimation. ITPD-E contains 170 industries, 265 countries, and covers the years 1986 to 2019 (services industries only from 2000 onwards, and 2019 having substantial gaps).

ITPD-E contains trade data for the UK as a whole. To carry out Scotland-specific gravity modelling various other sources of data (including Scottish Government and ONS supply–use tables (SUTs) and Export Statistics Scotland (ESS)) were used to split UK flows in ITPD-E into Scottish and the rest of the UK flows.

SIBTD contains 25 industries, 43 countries, and covers the years 2002 to 2019. The loss of industry granularity results from the need to aggregate to a common industry classification in order to combine ITPD-E data and SUT/ESS data. The dataset starts in 2002 because this is when ESS starts. The decision to use a smaller set of 43 countries is partly motivated by availability of ESS data, but it is worth noting that these 43 countries account for over 90% of world trade, and the results of gravity estimations are not usually particularly sensitive to the choice of whether to include the smaller countries.

C. Revealed comparative advantage

Comparative advantage is an important concept in international trade. A country is said to have a comparative advantage in a given sector if it can produce products in that sector at a lower cost than other countries. In theory, one would then expect countries to produce more of products in which they have a comparative advantage and import products where they do not have an advantage.

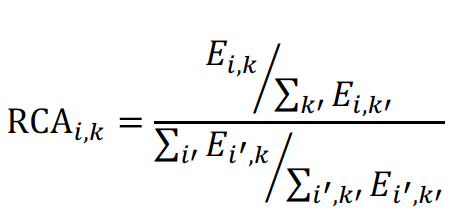

Revealed comparative advantage (RCA) is a way of quantifying comparative advantage using real trade flows by inverting the above logic. A country’s RCA for a sector k is defined by

Where i denotes the country in question and the dummy variables i' and k' are summed over all countries and industry sectors. In other words, a country’s RCA in a sector is the fraction that sector contributes to the country’s total exports divided by the corresponding ratio for all countries summed together.

We have calculated the normalised RCA according to

In order to obtain values between -1 and 1. We have calculated these using the Scottish International Bilateral Trade Dataset in order to inform the discussion of what might be driving the results we have obtained in our main analysis. Results for Scotland, the UK, the EU, and the four FTA partners are shown below. A few particularly large comparative advantages have been highlighted in bold.

| Industry sector | Scotland | UK | AUS | IND | CHE | TUR | EU27 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Agriculture, forestry, fishing | 0.04 | -0.56 | 0.40 | 0.16 | -0.89 | 0.24 | -0.37 |

| Mining & quarrying | 0.66 | -0.17 | 0.85 | -0.48 | -0.95 | -0.24 | -0.77 |

| Food and beverages | 0.56 | -0.10 | 0.22 | 0.04 | -0.22 | -0.07 | 0.07 |

| Textiles, clothes, leather | -0.29 | -0.47 | -0.89 | 0.58 | -0.66 | 0.68 | -0.17 |

| Wood, paper, printing | -0.39 | -0.33 | -0.41 | -0.66 | -0.50 | -0.39 | -0.02 |

| Coke, refined petroleum, chemicals | -0.36 | -0.12 | -0.63 | 0.25 | -0.22 | -0.37 | -0.05 |

| Pharmaceuticals | -0.52 | -0.01 | -0.60 | 0.19 | 0.65 | -0.69 | 0.35 |

| Rubber, plastic, non-metallic minerals | -0.25 | -0.29 | -0.89 | -0.12 | -0.38 | 0.27 | -0.09 |

| Metals, fabricated metal, exc machinery | -0.52 | -0.03 | 0.14 | 0.03 | 0.38 | 0.25 | -0.14 |

| Computer, electronic, optical | -0.48 | -0.46 | -0.81 | -0.74 | -0.07 | -0.73 | -0.28 |

| Electrical equipment | -0.69 | -0.45 | -0.89 | -0.30 | -0.28 | 0.13 | -0.10 |

| Machinery and other equipment | -0.36 | -0.20 | -0.84 | -0.22 | -0.05 | -0.19 | 0.13 |

| Transport equipment | -0.56 | -0.01 | -0.92 | -0.40 | -0.77 | 0.31 | 0.07 |

| Furniture, other manuf., Repair, installation | -0.69 | -0.35 | -0.51 | 0.45 | 0.15 | -0.23 | 0.01 |

| Utilities | -0.69 | -0.54 | -0.99 | -1.00 | 0.07 | -0.46 | -0.06 |

| Construction | 0.51 | 0.18 | -0.61 | -0.17 | -0.25 | 0.52 | 0.20 |

| Wholesale and retail, | -0.44 | 0.37 | -0.72 | -0.13 | 0.22 | -0.08 | -0.01 |

| Transportation, storage | -0.07 | 0.06 | -0.53 | -0.48 | -0.06 | 0.11 | 0.19 |

| Accommodation, food services | 0.01 | -0.04 | -0.32 | -0.34 | -0.13 | 0.16 | 0.01 |

| Information and communication | 0.24 | 0.30 | -0.42 | 0.58 | 0.18 | -0.77 | 0.23 |

| Financial and insurance | 0.56 | 0.67 | -0.45 | -0.65 | 0.33 | -0.77 | 0.09 |

| Professional, scientific, tech., admin., support | 0.30 | 0.50 | -0.41 | 0.27 | 0.03 | -0.62 | 0.19 |

| Education | 0.68 | 0.24 | -0.31 | -0.67 | -0.65 | -0.82 | -0.35 |

| Other services | 0.75 | 0.30 | -0.81 | -0.22 | 0.08 | 0.30 | 0.03 |

Source: SG OCEA calculations using Scottish Government supply-use tables and International Trade and Production Database for Estimation

D. Computable General Equilibrium model

A Computable General Equilibrium (CGE) model consists of a series of equations based on economic theory which describe the behaviour of agents in an economy (firms, households, and government). It is also a standard tool for trade policy analysis.

In this analysis, a two-region version of the Scottish Government’s CGE model is used, incorporating both the Scottish and the rest of the UK economies. Some of the key assumptions underpinning the model are covered below but for further detail please refer to Computable General Equilibrium modelling: introduction – gov.scot (www.gov.scot)

- Changes in trade costs are sourced from the gravity model estimations and are introduced in the model for both exports and imports broadly in line with the approach outlined in The long‐term economic implications of Brexit for Scotland: An interregional analysis – ScienceDirect

- The model assumes regional bargaining in the labour market (a negative relationship between real wages and unemployment); fixed government spending so that any changes in government revenues are absorbed by changes in the fiscal balance; that investors and consumers are forward looking; and that Scotland is a small open economy, too small to affect significantly any global prices.

E. Sensitivity Analysis

To explore how sensitive the results are to the choice of key parameter values, gravity and CGE simulations are also run with higher or lower values of trade elasticity and trade cost changes. This aims to account for uncertainty around the central estimates presented in the main body of the report.

In addition, there are many choices one can make in specifying the gravity estimation, with some ongoing discussion in the literature as to best practice. To investigate whether the partial estimates from the gravity model are sensitive to the particular choices made, various alternative specifications were explored, covering different choice of years used in the estimation sample, using symmetric and asymmetric pair fixed effects, border–year fixed effect, and different clustering approaches. As expected, some of these alternative specifications produced different estimates but did not fundamentally alter the key findings of this analysis.

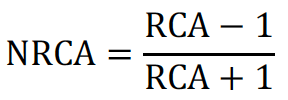

Gravity

For the main analysis, a trade elasticity of 4 is used following the default specification in GE Gravity R package. In practice elasticities can vary significantly by sector. For example, a recent paper by Fontagne et al. (2022)[33] showed considerable heterogeneity in trade elasticity across products and with an average elasticity of around 5. To investigate how sensitive the results are to the choice of trade elasticity, simulations are also undertaken with trade elasticities of 3 and 5. The results are shown in Figure E1 and E2.

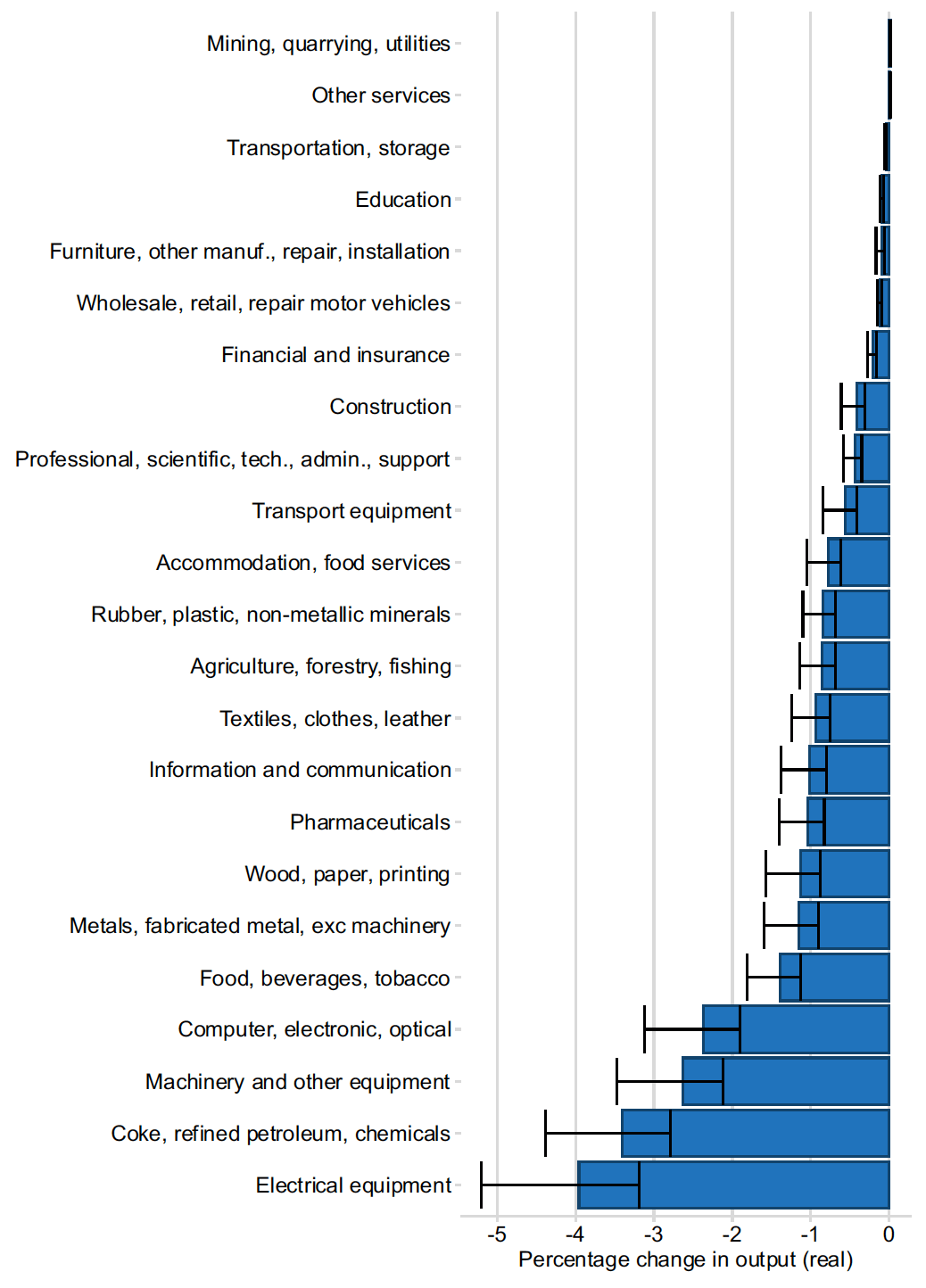

Figure E1: Sensitivity Analysis, Trade Elasticity, all four non-EU FTAs

Source: SG OCEA gravity modelling

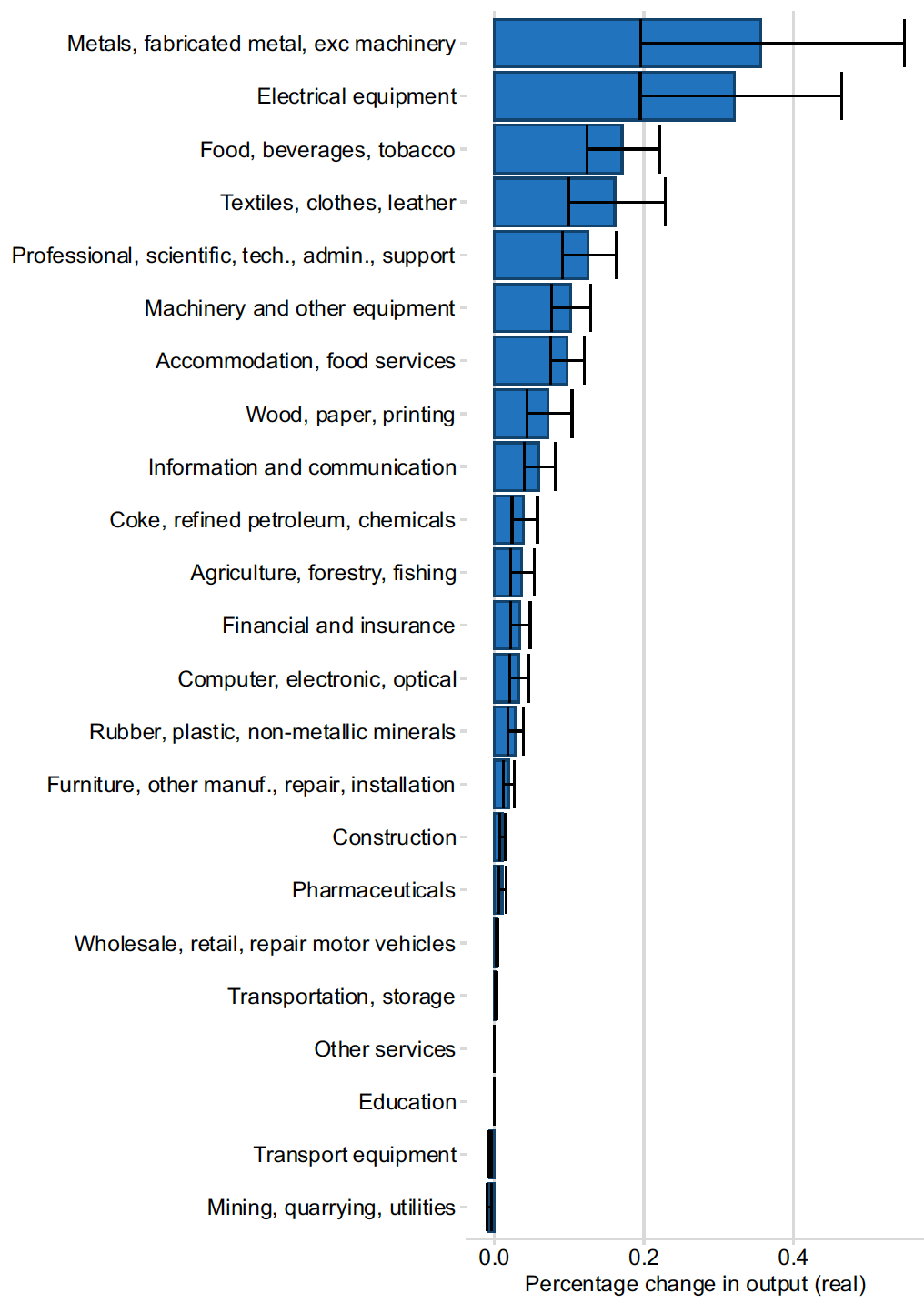

Source: SG OCEA gravity modelling

We have also analysed how sensitive the results are to the trade cost estimates. The first stage in our analysis is to estimate trade cost changes as a result of an FTA, before using these estimates as inputs to the General Equilibrium simulations. Because the estimates are found by an econometric procedure using real trade data, they carry some degree of uncertainty, which is quantified by the estimator in the form of a standard error. We use this standard error to define upper and lower values for the sensitivity analysis, one standard error above and below the central estimate.

However, some of our estimations fail to reach statistical significance with our input data. For these sectors, we have used estimates from Borchert et al. (2020). Because these are at a more granular industry classification and we have no robust way to aggregate standard errors, we have chosen to simply use an illustrative fractional error of plus or minus 35%, informed by the fractional errors we find in our own estimates.

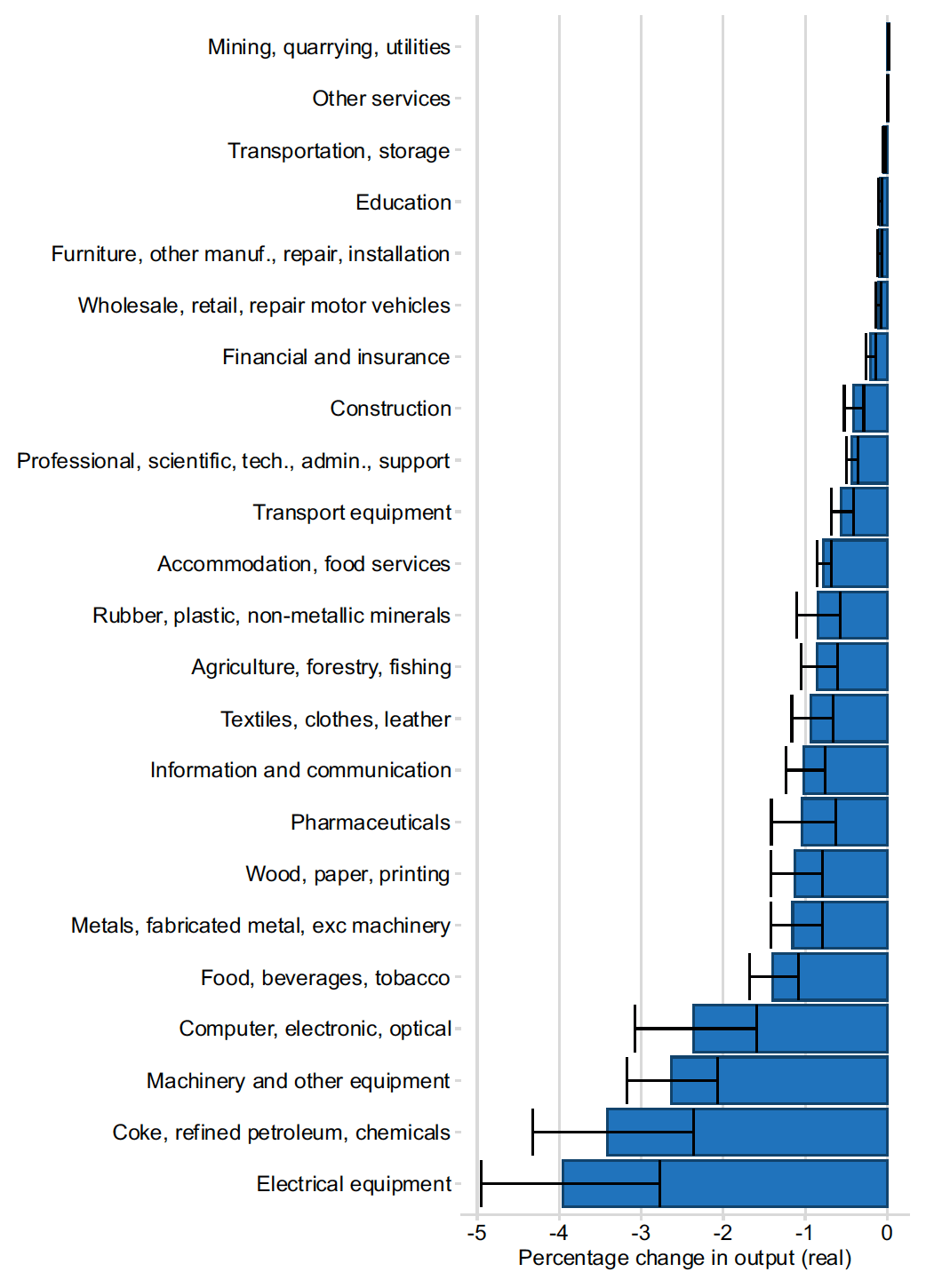

The results are shown in Figure E3 and E4. Note that we use the standard trade elasticity of 4 for these simulations.

Source: SG OCEA gravity modelling

Source: SG OCEA gravity modelling

Computable General Equilibrium analysis

A sensitivity analysis was also undertaken in the CGE model using upper (a higher increase in trade costs relative to the central scenario) and lower (a lower increase in trade costs relative to the central scenario) estimates of the trade cost shock and varying trade elasticities in the model. The trade cost shocks used in the CGE sensitivity run are similar to the inputs used for an equivalent exercise in the gravity model. The default values of trade-related elasticities (Armington, CET) in the CGE model were either increased (from 2 to 4) or decreased (from 2 to 1.5) for sensitivity analysis. Table E1 provides a summary of the sensitivity analysis for Scenario 2. Furthermore, the results of the model are also sensitive to the choice of model closure (e.g. labour market or fiscal closure).

| Scenario | % change relative to the baseline |

|---|---|

| Central estimate | -2.0% |

| Lower increase in trade costs | -1.4% |

| Higher increase in trade costs | -2.7% |

| Lower elasticities | -2.1% |

| Higher elasticities | -1.7% |

Source: CGE modelling

Contact

Email: EUEA-SG@gov.scot

There is a problem

Thanks for your feedback