National Flood Resilience Strategy: consultation analysis

Analysis of the responses to the National Flood Resilience Strategy consultation exercise.

Changing the narrative

The current approach to managing flooding has tried to fix flooding problems to allow us to continue to do the same things in the same places with a reduced exposure to flooding. Going forward, it will be necessary to create flood resilient places, reducing flood exposure and taking actions to lessen the impacts when flooding does occur. Influenced by engagement to date, the Scottish Government proposes that the key principles underpinning the new Flood Resilience Strategy should be that:

1. We will change the focus from ‘fixing flooding problems’ to creating flood resilient places.

2. Flood resilience is part of community resilience and part of adapting to climate change.

3. At the heart of our flood resilience activities will lie the principles of a Just Transition (to secure a fairer, greener future for all by working in partnership to deliver fairness and tackle inequality and injustice).

4. Everyone benefits from flood resilient places, and we all have a contribution to make.

Question 1: Do you support the change from fixing flooding problems to creating flood resilient places? Why/why not?

Responses to Question 1 by respondent type are set out in Table 2 below.

| Type of respondent | Yes | No | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| Environmental or planning body or group | 12 | 0 | 12 |

| Flooding or land management group or business | 3 | 1 | 4 |

| Local authority or regional planning group | 14 | 2 | 16 |

| Professional or representative body | 10 | 1 | 11 |

| Public body or agency | 12 | 0 | 12 |

| Third sector or political group | 5 | 0 | 5 |

| Total organisations answered | 68 | 6 | 74 |

| % organisations answered | 92% | 8% | n/a |

| Individuals answered | 83 | 27 | 110 |

| % individuals answered | 75% | 25% | n/a |

| Total all respondents answered | 151 | 33 | 184 |

| % all respondents answered | 82% | 18% | n/a |

A considerable majority of respondents – 82% of those answering the question –supported the change from fixing flooding problems to creating flood resilient places. The proportion of organisations supporting the approach was greater for organisations (92% of those answering) than for individuals (75% of those answering).

Around 170 respondents went on to make a further comment. Key themes from these further comments are summarised below.

Reasons for supporting the change

Many of those who supported the change made general observations that it appears to be the sensible and common-sense way forward, particularly in the light of climate change happening faster than has been predicted.

There was a view that Scotland needs to take more impactful action at significant pace, and that there is a strong and clear case for change. This was sometimes associated with a view that ‘prevention is better than cure’ and that the focus needs to shift away from being reactive. This was seen as especially important given that the full implications of the transition to a different climate remains uncertain, but also that many climate impacts, including sea level rise and flooding, are already locked in and unavoidable.

Moving away from ineffective and costly solutions

One of the reasons some respondents gave for supporting the change to creating flood resilient places was that they did not think more traditional, hard engineering solutions are sufficiently effective or flexible. There was a view that current hard engineering solutions cannot cope, with infrastructure not able to meet the needs of the places to be protected from flooding.

Further comments included that:

- It does not seem possible to build flood defences that will protect against all risk and all scenarios; resilience measures can be more flexible and responsive to impending events.

- Hard flood defences do little to challenge the underlying causes of flooding. It was also noted that engineering-based solutions are becoming more expensive, both in financial terms and in relation to carbon cost. In terms of carbon, it was noted that this applies to both the carbon cost of construction and the embodied carbon in materials, and it was argued that creation of hard flood defences may contribute to climate change.

In terms of financial costs, some respondents suggested that prevention is more cost-effective than fixing problems, and that improving flood resilience is likely to be a more economically viable and sustainable way of managing flood risk in many cases.

Working with nature

For some respondents, the change from fixing flooding problems to creating flood resilient places, reflects the inevitability of needing to work with nature rather than trying to fight it.

It was suggested that taking a more holistic, nature-based approach is the most logical way forward, especially since by creating flood resilient places we can reduce the impacts from flooding in the first place. It was also argued that the use of nature-based solutions will benefit people and nature, for example by reducing costs of flood repairs and delivering benefits such as improved water quality, increased biodiversity and urban cooling.

Promoting agency and achieving buy-in

Whilst it was noted that flood resilient places will mean different things to different people, it was also hoped that shift in focus onto flood resilient places could lead to more people becoming involved and increased awareness about flooding across communities. This was connected to a suggestion that a positive, proactive framing is more likely to gain support for discussions and action, and should give people agency.

However, although it was seen as important to empower communities to help themselves become resilient to flooding and other effects of climate change, there was also a view that it is not advisable to place the responsibility for flood resilience mainly upon communities. The associated point was that flooding issues that affect communities further down a catchment are unlikely to be resolved without addressing land use and water management issues further upstream.

Caveats or conditions

Perhaps reflecting some of the challenges around creating flood resilient communities set out above, some respondents did note that their support for the approach was conditional upon certain circumstances applying or conditions being met. These included there being:

- A wholescale consideration of legislation, remits and processes, with the creation of a clear and shared vision for organisations to follow and work towards.

- Clarity for communities with respect to how improving resilience is measured, how the Scottish Government can support their efforts, and what a resilient community looks like.

- Increased support and resources for communities in preparing for and responding to flooding events; it was suggested that such support could make it easier for communities at risk of flooding to leverage resource, helping to ensure that they have the necessary knowledge and infrastructure to prepare and respond.

- Greater consideration of flood resilience in the planning system.

There was also reference to the need to improve performance data and put appropriate national standards in place.

Both approaches bring value

A frequently made point, including amongst those who had answered either ‘Yes’ or ‘No’, or who had not answered the closed question, was the need to continue fixing flooding problems as well as seeking to create flood resilient places.

These respondents tended to the view that, while flood resilience should be the goal, some fixing of flooding problems will still be needed, including as part of creating those flood resilient places. It was suggested that resilience is a long-term approach, but that:

- There are places where retrofitting will not be an option, even in the medium term. Considerable hard engineering will still be required to protect people and property.

- The focus should be on designing new developments to be flood resilient.

In summary, this group of respondents saw a need to transition to a better balance with more emphasis on flood resilient places, whilst acknowledging that there will be circumstances where a specific local intervention may be the most effective approach.

Reasons for not supporting the change

Those who did not support the change were most likely to be concerned about a shift away from protecting communities, homes and businesses that are at greatest risk from flooding. Some Individuals respondents were amongst those suggesting that communities affected by flooding deserve better than their government trying to shift responsibility for flood resilience onto them, and that it is not fair to leave those at risk feeling abandoned and left to fend for themselves.

There was also a concern that the change in emphasis or focus could lead to funds being redirected away from pure protection actions, meaning they will be undeliverable. There was a call for a balance to be struck between investing in fixing flooding problems and the potential loss of investment, businesses and homes within areas that may be at risk of flooding by the year 2100. It was suggested that the financial cost of such losses needs to be understood and, where appropriate, the ‘fixing flooding problems’ approach maintained.

Finally, there was a suggestion that the proposed approach does not really represent a significant change, since ‘fixing’ flood problems has never been the position and the focus has long been on making communities more resilient.

Question 2: How can decision makers ensure that actions taken to improve flood resilience align with the aims of a Just Transition to achieve a fairer, greener future?

Around 175 respondents answered Question 2. Points included some broad statements in support of a focus on a Just Transition and specifically on tackling climate change and biodiversity loss. However, a small number of others either questioned why the issues of flood resilience and a Just Transition are being so closely linked, or suggested that a Just Transition is an unhelpful distraction from the focus on protecting communities and businesses from the impact of flooding.

Vision, leadership and joint working

It was suggested that aligning actions to improve flood resilience with the aims of the Just Transition will require a clear and shared vision for flood management that provides a hierarchy of priorities and ensures that the aims of Just Transition are embedded through the entire process.

Some respondents also made the connection to other strategic and policy priorities across Scotland, and it was suggested that key to maximising the benefits for a Just Transition will be combining a strategy and actions for flood resilience with other related strategies, legislation and policy. There was reference to:

- The Climate Change Act 2019, which itself embeds the principles of a Just Transition.

- The National Planning Framework 4 (NPF4).

- The Scottish National Adaptation Plan 3 (SNAP3); there was reference to the inclusion of emission implications in optioneering as well as looking for development to offset emissions.

- The Scottish Biodiversity Strategy and Wild Salmon Strategy.

In terms of how the wider planning system, and the type/range of flood management approaches adopted, can be best aligned with the aims of a Just Transition, it was suggested that Scotland will need:

- Leadership that is collaborative and works in a coordinated way to create a cohesive framework.

- Clear objectives and markers against which decisions and actions can be tested, with decision makers ensuring that actions taken reflect the policy and guidance that is in place.

- Clear governance arrangements.

- A willingness to shift quickly and adapt, including to changing predictions of both climate and ocean-level rises.

Local authority and regional planning group respondents also referred to the need to break down siloed working, including through the identification of overlaps in work across projects and stakeholders. In terms of stakeholders, there was reference to the importance of working together with those not typically within the flooding specialism.

Local authority and regional planning group respondents were also amongst those who went on to address decision-making approach and processes that could ensure that actions taken to improve flood resilience align with the aims of a Just Transition, with suggestions including that:

- There could be benefit in looking at the approach used for Local Heat and Energy Efficiency Strategies (LHEES). These strategies require prioritising action in areas of fuel poverty and focus on place-based solutions.

- Feasibility and optioneering phases should consider a wide range of benefits and impacts, including the aims of a Just Transition. Guidance on how this should be done would be beneficial to ensure a consistent approach is applied across Scotland by both local authorities, Scottish Water and others.

- All stakeholders need to be engaged in strategic discussions at settlement, or catchment level. Stakeholders within an affected area may then shape adaptation and benefit from measures to be taken to reduce flood risk in future.

Partnership working with local communities

The vital role of genuine partnership working with local communities was a frequently raised issue, particularly among Individuals and Community Council or group respondents, but also by a number of Local authority or Public body respondents. There was a call for local and national governmental agencies to work with Community Councils, Development Trusts and other community groups to understand what a local response to flood resilience should look like.

In terms of how best to involve communities in developing flood resilience plans, comments included that the decision-making systems and processes used throughout must be collaborative and inclusive and that public bodies have to truly listen to local people and communities impacted by flooding. Involving and supporting people and communities in flood resilience strategies is the focus of the ’People’ section but, in summary, points raised at this question included that:

- Partnership working needs to use modern principles of community engagement, with local residents supported to build-up knowledge and skills and develop networks. Those tasked with responsibility for developing strategies should be offered training in truly inclusive collaboration and engagement processes.

- Not all members of communities will be equally confident to actively engage in decision making; attempts by local people to communicate in ways that they are comfortable with need to be respected.

- It will be important to take time to get everyone on board, not just stakeholders but also those that often prefer to take a back seat.

- It is critical that disabled people are involved. Decision makers should involve and resource Deaf and Disabled People’s Organisations to ensure they are not further excluded from society or placed at greater risk from flooding.

Respondents also highlighted the importance of local communities being involved in the earliest stages of project formulation and design. To support that involvement, there were calls for:

- Better education and awareness of how flood resilient measures can be integrated into projects.

- Complete transparency in the decision-making process, including by publishing non-technical summaries well in advance of decision making.

Very much connected to both the best use of resources (discussed further below) and partnership working with local communities was an emphasis on decision makers really considering the local context. In addition to their views, suggestions for community-related factors to be taken into account included:

- The economic, social and health vulnerabilities of the communities likely to be affected.

- Local Place Plans.

Recognising particular vulnerabilities

In addition to general references to socio-economically disadvantaged communities, the particular vulnerabilities that some communities, or members of communities, can experience were highlighted.

A Public body respondent highlighted the negative impact of flooding, or threat of flooding on children and young people and suggested that flood adaptation should be seen as a children’s rights issue. They set out how children’s physical and mental health can be impacted, and reported that children are known to be acutely affected during and after floods, losing their homes, friendship networks and familiar surroundings.

Remote rural communities were also identified as suffering disproportionate damage compared to their urban counterparts. It was reported that road infrastructure, bridges and transport can all be more severely impacted and that it is also likely to take longer to reinstate and repair than in urban settings.

Investment and resources

In addition to general observations that the delivery of the Strategy will need to be funded, a Public body respondent called for an inclusive funding mechanism that recognises scope for non-traditional flood actions and broadens the prioritisation criteria beyond financial cost and benefits.

Prioritising use of resources

A frequent theme was the need to focus on fairness, including a view that the wider costs of water management need to be spread more equitably. The associated position was that the costs of flood mitigation should not be borne just by those individuals who suffer the highest impacts and/or who are most vulnerable. However, there was some divergence of views around who should be seen as in greatest need.

For some, the focus should be on investing in flood protection infrastructure that benefits those most vulnerable to flooding. For these respondents, the focus needs to be on the assessment of the risk presented by severity and likelihood of flood impact. Associated comments included that it would not be a Just Transition if individuals and their businesses suffer while flood resilience measures are focused on benefitting the majority. However, an alternative view was that it is not fair to sink major resources into schemes that benefit single or only a few communities.

Some other respondents were very much focused on socio-economic circumstances, and on the importance of prioritising people and communities that have limited access to financial and other resources. For example, a Local authority respondent commented that decision makers will need to accept that some degree of ‘engineering’ of the system will be needed to achieve equitable outcomes. They went on to report that decisions on flood resilience are generally being made on flood hazard maps that highlight areas at risk, failing to take into consideration the extent to which communities in these areas are actually able to become resilient.

Further observations included that people living in lower value properties may be much less vocal than those who are more affluent, and also that opportunities to transition homes to lower carbon footprints have favoured higher income households and homeowners with financial incentives. There was a call to ensure that flood resilience measures avoid deepening this inequity, and for financial assistance focused on helping poorer people and communities improve resilience.

Further suggestions included:

- Introducing metrics into the prioritisation process that include social vulnerability scores.

- Applying a weighting to benefit cost calculations for flood resilience measures in socially deprived areas.

There were also comments about the types of places or communities that should be prioritised for flood resilience-related funding and support. They included that, to date, resources tend to have been directed towards protecting urban areas from flooding, and many rural dwellings have received no help at all.

Approaches to agricultural and land-based subsidies

Other comments focused on the use of subsidies to improve flood resilience, with a suggestion that we need to look again at subsidies for agriculture and land ownership. Going forward, it was suggested that Scotland should:

- Offer funding for wetlands, set aside land and beaver habitat.

- Create river corridors and pay for their management.

- Provide funding for community tree planting schemes.

Planning system, policies and consents

Some Individual respondents were amongst those of the view that the planning process needs to place more emphasis on flooding, including in relation to planning application assessments. Specific points or policy suggestions included that:

- Fit-for-purpose infrastructure needs to be prioritised. For example, towns and cities have been expanding much faster than the sewer network infrastructure which is no longer fit for purpose in many places.

- Building/development on flood plains needs to be stopped.

- The amount of housing development on greenfield sites needs to be reduced.

- The focus needs to be shifted from new build to retrofitting and town centre regeneration.

- Social housing should not be built in areas of flood risk; if required, this could be supported by the compulsory purchase of land that is not at risk.

- Building standards should be amended to ensure any new build is flood resilient, for example having flood doors and automatic vents, irrespective of perceived risk.

Reflecting more general points raised earlier, a Community Council or group respondent suggested that local authorities should be required to take the views of local residents – including their local knowledge about flood risk and flooding areas – into account when considering planning applications.

Land and flood management approaches

Other comments addressed the type of approaches to land and water management that can help create and maintain flood resilient places, including some general statements in support of using nature-based solutions.

Rural land management

As in relation to funding and subsidies, some respondents addressed rural land management and agricultural practices, with suggestions including that we need a shift away from damaging land use practices, including the overgrazing of uplands and the management of land for sheep, grouse and deer. Such practices were described as a primary contributor to flood risk to downstream communities, and there was a call for landowners to be held accountable when their actions cause or contribute to flooding of downstream communities. A specific suggestion was the creation of a ‘responsible land use index’ that rewards good land management and penalises actions that cause flooding or impact local communities.

A different perspective, including from a small number of Professional or representative body respondents, was that while farmers and land managers have a key role to play in managing water and mitigating flood risk, they need to be supported and incentivised to mitigate flood risk, with a specific suggestion that financial support for farmers to manage waterways and take other water management measures will be key to the Strategy’s success.

Suggested land and flood management approaches

A number of approaches that could or should be adopted as part of the overall approach to building flood resilience were suggested. In terms of land management suggestions included:

- Reducing the use of hard concrete structures where possible. However, it was also noted that it may be necessary to use non green solutions to deliver flood resilience, and that PAS 2080 can provide guidance on managing the impact.

- Encouraging the creation of reed beds.

There were also suggestions relating to drainage or watercourse management, which included:

- Legislation and dedicated funding for rainwater management as part of active travel and placemaking projects.

- Allowing tree and shrub planting along water courses and better maintenance of watercourses allowing for unimpeded flow.

Information sharing, monitoring and evaluation

Better information was described as key to ensuring that people fully understand the issues, the drivers, and the potential range of alleviation measures. A number of respondents pointed to the need to improve the evidence base, including to ensure that decision makers are not influenced to exclude natural flood management (NFM) approaches because of uncertainty of the exact effects in reducing flood risk levels. Specific suggestions included that:

- NFM Benefits Valuation would show more fully the ‘financially valued’ benefits of NFM to human well-being, wider society and biodiversity.

- The effects on delivering emissions reductions should be estimated.

In terms of how the local evidence base could be improved and/or kept as up to date as possible, suggestions included:

- Reviewing Sustainable Drainage Systems (SuDS) in developments where these result in greater likelihood of overbank flooding of properties downstream.

- Supporting local groups who can monitor and record specific local flooding when it happens.

In terms of the Strategy overall, and the contribution to being made to delivering a Just Transition, comments included that a national monitoring and evaluation programme will be required; this would both track and report progress of actions against the aims of a Just Transition and increase consistency in the reporting of actions.

Wider impact from a Just Transition

While many of the comments addressed the direct impact of flooding and/or increasing resilience against flooding, others considered the how the delivery of the Strategy could impact on a Just Transition more widely. The focus was generally on job creation and the potential to help catalyse a boom in highly skilled and valued green jobs. Associated suggestions included that, in line with the principles of the Just Transition and inclusive economic development, there should be additional support to local populations and those facing disadvantage to ensure that these new jobs are accessible to them.

Other benefits identified included health benefits associated with sustainable transport networks and ensuring equitable greenspace access.

However, it was also noted that some issues or potential challenges may need to be addressed if the delivery of the Strategy is to make a positive contribution to a Just Transition. These included:

- The availability and affordability across the country of the appropriate skills to understand risk and to plan and implement flood resilience measures.

- The cumulative financial effects of net zero and flood resilience requirements on building and landowners and operators.

- The availability and cost of insurance for a flood resilient approach.

Question 3: Who do you think has a role in Scotland to help us become more flood resilient and to help us adapt to the impacts of climate change? (Please rank from most to least important)

Eleven options were presented at this question:

- Individuals

- Homeowners

- Businesses

- Scottish Government

- Scottish Water

- Local authorities

- Scottish Environment Protection Agency (SEPA)

- Landowners/land managers

- Farmers and crofters

- Housebuilders/developers

- Community groups

Around 180 respondents responded to this question. This included by ranking some or all of the options given, and/or by making a further comment in relation to the ‘Other’ option.

Most and least preferred options

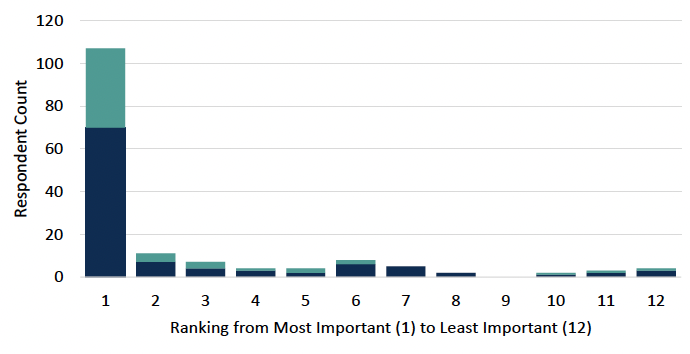

Respondents were most likely to think that the Scottish Government has the most important role to play in helping Scotland to become more flood resilient and to adapt to the impacts of climate change. A majority of those answering the question (107 respondents) ranked the Scottish Government as most important. Figure 1 shows the distribution of the rankings allocated to the Scottish Government, with individuals in blue and organisations in teal.

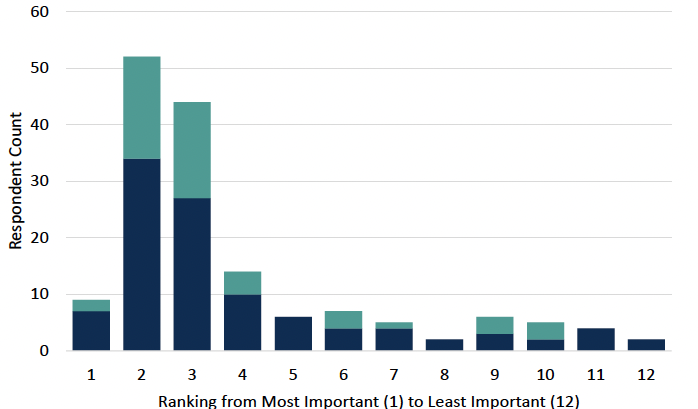

After the Scottish Government, respondents tended to see other public sector organisations as having an important role to play. These included local authorities, followed by SEPA and Scottish Water. Figure 2 shows rankings allocated to local authorities, often chosen as having the second or third most important role.

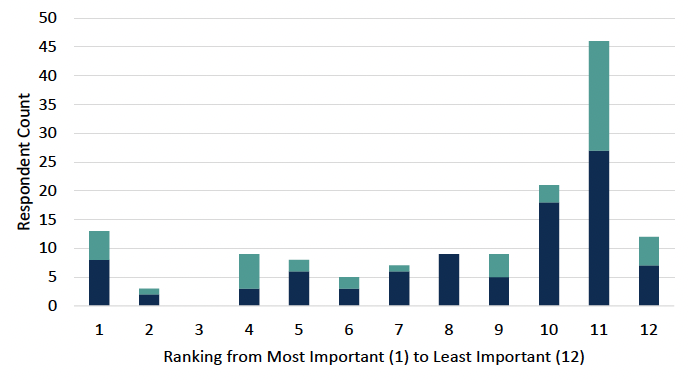

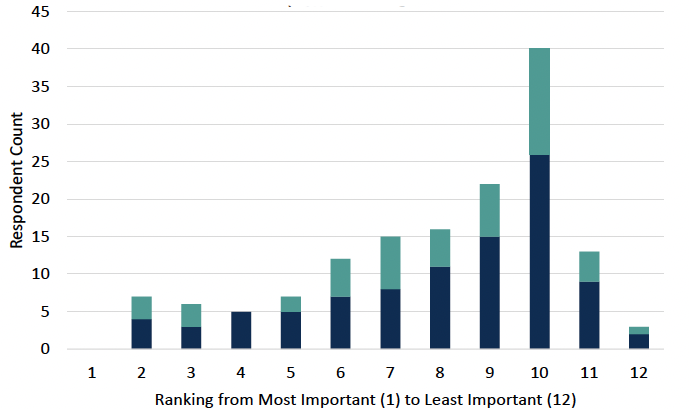

A number of (generally) private sector groups tended to be ranked as of middling importance: farmers; landowners; housebuilders and businesses. Both organisations and individual respondents were most likely to see community groups, homeowners and individual members of the public as having the least important role to play.

(Please see Annex 2 for a full numerical analysis and all charts for Question 3.)

Some respondents argued that all the options listed are all important, or are of equal priority and should not be ranked. There was also a view that the context will be different for each catchment area. The same basic objection was also cited at other questions where respondents were asked to rank a number of options and, although some respondents expressing these views did offer a ranking, others did not.

‘Other’ suggestions

Around 80 respondents made a further comment in relation to the ‘other’ option.

Among suggestions for others who could have a role in helping Scotland to become more flood resilient, the most frequent were:

- NGOs and/or charities (such as Adaptation Scotland, Sniffer, Scottish Flood Forum and River Trusts).

- Named public bodies (NatureScot, Forestry and Land Scotland, Scottish Canals, Historic Environment Scotland and the Cairngorms National Park Authority).

- Infrastructure owners and operators (such as Transport Scotland, Sustrans and Network Rail).

- Schools and universities.

- The insurance industry.

- Mortgage providers/brokers.

Less frequent suggestions included:

- Emergency Services.

- Health/mental health organisations.

- Disabled people’s organisations.

- Housing Associations and private rented sector landlords.

- Planners.

- Specialist consultants.

- Professional bodies.

- Hydroelectricity companies.

- Fishing clubs.

Contact

Email: flooding_mailbox@gov.scot

There is a problem

Thanks for your feedback