National guidance for child protection 2021: consultation report

This report shows the results of the public consultation on the revised national guidance for child protection in Scotland, and our response to the results.

Practices and Processes

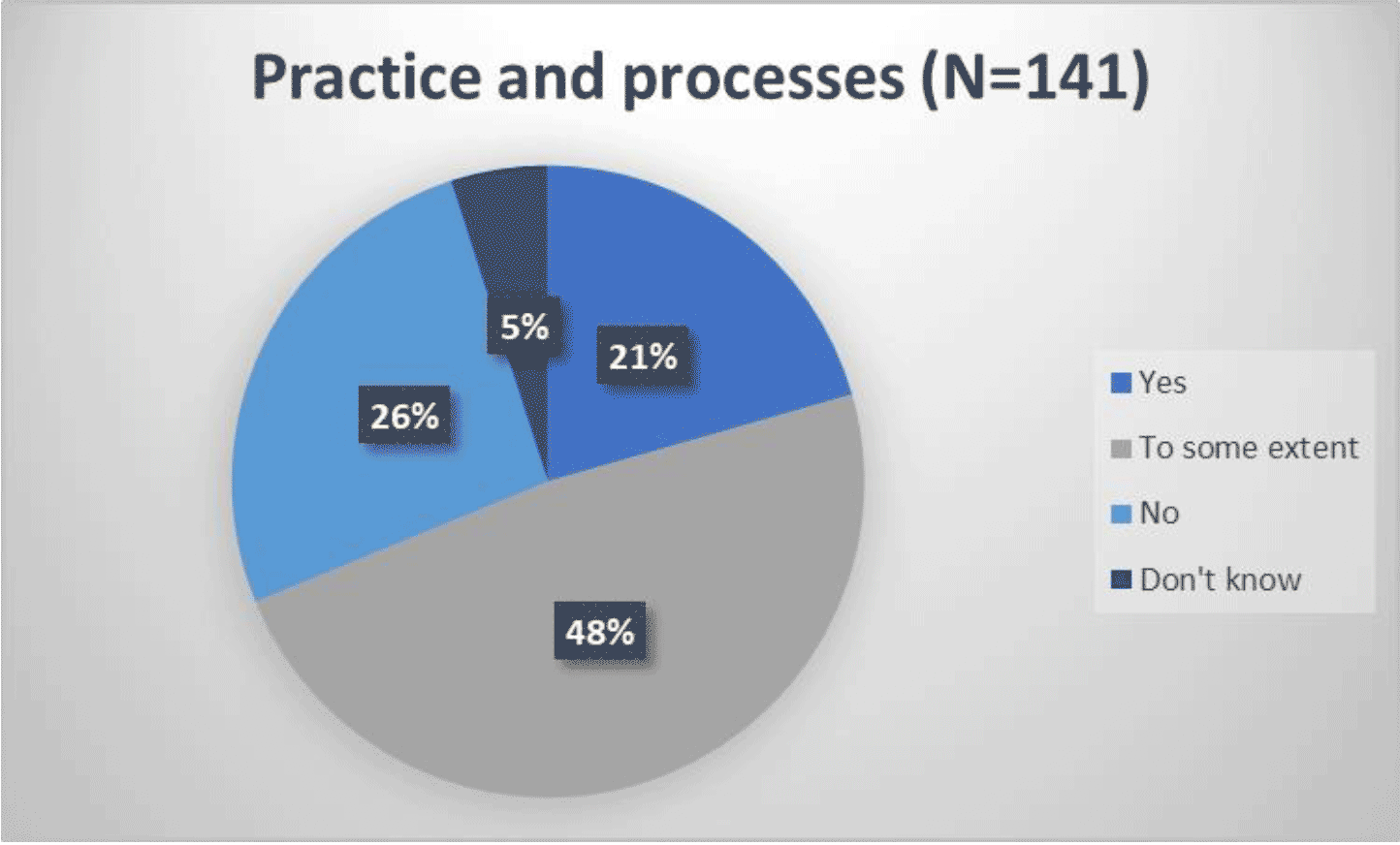

Q4: Practices and Processes - Part 3 seeks to accurately and proportionately describe the practice and processes critical in the protection of children.

Are there any practices or processes that are not fully or clearly described in the guidance?

Stakeholder Event Themes

The main themes raised at the stakeholder events were:

The change of name from Child Protection Case Conference to Child Protection Planning Meeting was seen as more inclusive for the families and children, but the importance of the meeting must be retained.

The previous 2014 guidance was stronger on transfer, including the timescales and expectations between local authorities.

The guidance on information sharing could be clearer, including what can be shared by health or education staff on 16 – 18 year olds.

Concerns were expressed about the realism of some timescales. For example, producing a written report on the Child Protection Planning Meeting within 5 days could be a struggle for some areas.

It was suggested that there could be reference to MARAC in this section.

The majority of respondents (74% of those answering the question - a combination of those answering 'yes' and 'to some extent' ) thought there are some practices any practices or processes that are not fully or clearly described in the guidance.

Around 95 respondents made a further comment at Question 4. Some of these respondents repeated comments made at earlier questions or gave views on other parts of the guidance. Those reflections are covered in the appropriate section of the analysis and are not repeated here.

Many of the general comments on Part 3 acknowledged the prescriptive nature of this section. The perceived advantages of this were that the guidance offers a level of detail that can support consistency in practice across Scotland. Some respondents felt this would give them confidence in local implementation. However, a more common observation was that, in being directive, the guidance would be challenging to implement as there is a need to maintain local flexibility, reflecting the contextual differences in various areas. The broad consensus was that local variations will have to be applied. It was suggested that the section be prefaced by a statement confirming that provision is made for local implementation.

Other observations included:

- Rural and remote areas should be given greater emphasis.

- The tone of Part 3 appears to be out of step with the rest of the guidance, most of which focuses on relationships and the space for professionals to be curious.

- Part 3 does not reflect the partnership approach with families which should be embedded across the guidance.

- It is not clear that the impact of, or learning from, The Promise has been reflected, for example in relation to risk or empowering families.

- Core processes are outlined, with the exception of the Child Protection Investigation, which is mentioned but requires more detail (perhaps in the IRD section).

- Guidance on Child Protection Case Discussions, which may be needed in complex cases, would be welcome.

- Good practice on transition planning and practice for vulnerable young people would be a useful addition.

The remainder of the comments were mostly focused on IRD, and the move from the Child Protection Case Conference (CPCC) to Child Protection Planning Meetings (CPPMs).

Inter-Agency Referral Discussions (IRD)

The comments about IRDs often reflected some of the general comments made in relation to Part 3, in particular the extent to which prescriptive guidance is a help or a hindrance. Whilst some welcomed the consistency of approach, they also recognised the challenges this creates. On a local level it was anticipated that:

- Identification of the lead professional may be difficult, depending on the processes within Social Work for allocation of cases.

- Where local practice is to allocate specific discussion slots to carry out an IRD, it would be challenging to implement the process set out within the draft guidance.

- Some of the proposals may be less practical in rural settings where frontline staff are more likely to attend IRDs but would not have the authority to make decisions on behalf of their organisations.

- In some areas, an IRD may be treated as a single event or a series of event up until a case conference. Moving to a standardised approach will be resource intensive on local services and timescales for standardisation would be helpful.

Suggestions for change or points about which clarification was sought included:

- Adding a clear statement about the purpose and intended outcome of an IRD.

- Clarifying when child protection referrals do not require an IRD.

- Setting out how Police, Health or Social Work can convene an IRD, including how to deal with any lack of consensus.

- Explaining how a non-lead professional (i.e. not Police, Health or Social Work) can request an IRD, and the procedure for decision making.

- Explaining how an IRD in a pre-birth referral is triggered.

- Giving examples of instances where concerns about a child do not meet the threshold for an IRD, whether on initial assessment or after a referral has been made to IRD.

- Confirming that an IRD can be held for a young person up to the age of 18 years.

- Clarifying who has responsibility for closing an IRD.

It was also suggested that it is not clear who writes the initial safety plan and agrees it and communicates with families. It is not included in the process flow chart, resulting in a lack of clarity about whether it is produced as part of the IRD.

Joint Investigative Interviews (JII)

Much of the commentary on JIIs was very specific and detailed. Points included:

- The guidance should state that trauma-informed principles are central to the Scottish Child Interview Model and are woven through this new model.

- While the IRD and JII are intrinsically linked in practice, there are very different training requirements linked to each. Any practitioner involved in conducting JIIs must have undertaken specific training.

- Guidance on the approach taken in JIIs should explicitly refer to supporting the child during interview, not just before and after.

- Where a JII and a medical examination are indicated, the order of these should be agreed in accordance with what is in the best interests of the child. The JII does not always need to take place first.

- It should be clearer that the IRD determines the overarching strategy for the child protection investigation, within which the JII sits.

Involving children and families in the child protection process

There was acknowledgment that child protection work can leave children and families feeling disempowered; ensuring they are at the centre is a challenge for all partners. The inclusion of a distinct section on the principles of involving children and families in child protection processes was therefore welcomed.

There were specific suggestions about how the guidance in Part 3 could be further improved. It was observed that the IRD section is formal, is weighted towards professionals, and does not reflect the partnership approach with families described in the guidance principles. Some respondents commented that the language and tone conveyed a 'doing to' families message, rather than being focused on working alongside and learning from parents. It was felt that the guidance could do more to ensure that the experiences, needs and 'voice' of children and families are integrated into the IRD process, even if it may not always be appropriate to gather the views and experiences of children and families at the commencement of an IRD.

Other points included:

- The language of 'child protection' can be a barrier to a family's participation. The use of 'safeguarding' to promote collective responsibility was suggested, with meetings titled 'Safeguarding Planning Meetings'.

- The impact of neurodiversity for example autism, or learning disability, should be considered in practice and processes, including how to provide information in accessible formats.

- Communication with children who do not have English as a first language should be considered.

- Guidance should take account of the overlap in processes where children and young people are looked after and also considered at risk of significant harm. It was noted that when children and young people are on the Child Protection Register, and subsequently accommodated, there can be a period of time where both processes are running in parallel, and the number of meetings can be overwhelming for families.

Guidance on working with families who do not engage during child protection processes would be helpful; the assumption appears to be that they will engage.

Child Protection Planning Meetings (CPPM)

Many of the comments on the section of the guidance covering CPPMs focused on the change in terminology from the previous Child Protection Case Conference. Whilst there was some acknowledgment that the name would be clearer for parents and children, and is positive in relation to GIRFEC and child centred assessment, some reservations were expressed. Comments included that:

- The rationale for changing the name should be made clear to avoid confusion amongst staff.

- The change of name may undermine the priority and seriousness of child protection interventions and the purpose of the Child Protection Case Conference. The wording 'Case Conference' is clearer and conveys more gravitas when other (less involved) professionals, such as mental health colleagues/GPs are being asked to attend.

- The abbreviation (CPPM) can mean different things to individuals or services, which could potentially lead to confusion.

- The implications for a Child Protection Case Discussion should be clarified.

- The Promise calls for a single Child's Plan, but this is not emphasised in the guidance. A Child's Plans arising from a CPPM was suggested as more appropriate.

Evidence in criminal proceedings

In relation to evidence in criminal proceedings it was suggested that:

- Further guidance on supporting child witnesses and the role of child protection services where families are involved in civil proceedings would be welcome. A connected comment was that there appears to be an assumption that a child's testimony would be verbal, and guidance on the use of, for example, the child's drawings or writing to communicate their views to the Court would be helpful.

- The guidance could be clearer on the interface between child protection planning and the Children's Hearing system, in particular the role of compulsory measures of supervision in making sure that a child protection plan is effective, and the need for early discussion with the Children's Reporter when concerns arise.

- The coverage of referral to the Principal Reporter could be strengthened with specific reference to Scottish Children's Reporter Administration (SCRA) materials.

Education Services

There were a number of comments reiterating the need for universal services, and in particular Education Services, to be given greater prominence in Part 3. It was felt that giving Education Services prominence would affirm the importance of a multi-agency approach. It would be particularly helpful in relation to IRD, where there currently appears to be a lack of formal involvement from education professionals.

The legal loophole that allows abusive parents to move children between independent schools and home schooling without any checks or visits was highlighted as an issue that needs to be addressed.

Domestic Abuse

Very much reflecting themes raised at other questions, there were detailed comments about the coverage of domestic abuse. Key points included that:

- The section on domestic abuse is overly focused on the non-abusing parent, with insufficient attention on how perpetrators should be managed, as promoted by the Safe and Together model.

- Guidance is needed about whether children discussed at Multi-Agency Risk Assessment Conferences (MARAC) and offenders discussed under Multi-Agency Tasking and Coordination (MATAC) protocols, and in particular those not already known to statutory services, should automatically be discussed at an IRD.

- A clear definition of coercive control, and an expansion of the risk posed to children and young people, should be included. A recognition that perpetrators can seek to use child protection systems as a way to continue abuse should be acknowledged.

- Clear guidance is required regarding the need for separate meetings for parents where domestic abuse or sexual violence is a factor, including the resource implications on professionals' time.

- A description of the national structure of the Domestic Abuse Investigation Unit, rape investigation units and public protection units across Scotland would be helpful.

Strengths-based practice

Strengths-based approaches was another theme highlighted, including that it would be helpful to have the concept explained within the guidance document, as the terminology is not widely understood across all agencies. Other comments and suggestions included:

- The strengths-based approach should be reflected across the guidance as a way of working alongside families.

- Family Group Decision Making (FGDM) has been highlighted as a strengths-based approach. The guidance could be enhanced by clarifying the advantages of the approach and its application at various stages of the child protection process.

- The section on involving children and families is aligned to the principles of Signs of Safety. This could be further expanded to consider the principles of good practice and strengths-based approaches.

- Whilst the term 'Child Protection Case Conference' should be amended to reflect a strengths-based approach, the function of the conference is important, and it would be inappropriate to move straight into Child Protection planning without an initial discussion.

Information sharing

In relation to information sharing, comments included that:

- The agency responsible for sharing information after an IRD should be set out.

- Information sharing approaches, especially as applying to 16-17 year olds, are not clear. Specifically, clarification is needed on seeking consent from 16-17 year olds when sharing information.

- Further information on how information can best be shared with families would be welcome. This should include instances when information should not be shared, for example if this may jeopardise a Police investigation.

Timelines

The change to the timescale for holding an initial CPPM from within 21 calendar days to within 28 days following the start of a child protection investigation was welcomed as a more realistic timeframe for undertaking an investigation. However, it was suggested that the rationale for this change should be made explicit, including through reference to the importance of an interim safety plan. The inclusion of a section on interim safety planning was also seen as a positive addition, helping agencies be clear about their specific responsibilities and enabling a relation-based assessment of the family circumstances.

The suggestion that there should be a full report of the CPPM within 5 days was considered challenging. It was reported that this is more detailed than action notes or a minute, would require additional resources and may not be achievable in the prescribed timescale.

Other timescale-related observations were:

- The guidance states that there should be a Review CPPM within 6 months of the initial CPPM. It was suggested that this does not reflect the ethos of a strengths-based approach and that, whilst 6 months could be a minimum standard, the needs of the family should be taken into account.

- More clarity in the section on the transfer of cases between authorities would be helpful. The previous guidance stated a maximum of 21 days of notification, but there is no specific timeframe mentioned in the revised guidance. It was also suggested that references to transferring child protection cases within Scotland should also refer to all UK authorities.

Finally, the status of the timescales set out in the guidance was described as unclear; there was a query as to whether they are advisory or mandatory, and whether subject to external scrutiny and/or inspection?

Contact

Email: Child_Protection@gov.scot

There is a problem

Thanks for your feedback