National guidance for child protection 2021: consultation report

This report shows the results of the public consultation on the revised national guidance for child protection in Scotland, and our response to the results.

Pre-birth assessment and support

Q10: Pre-birth assessment and support - Part 4 of the National Guidance sets out the context in which action is required to keep an unborn baby safe. Part 3 sets out the processes for this.

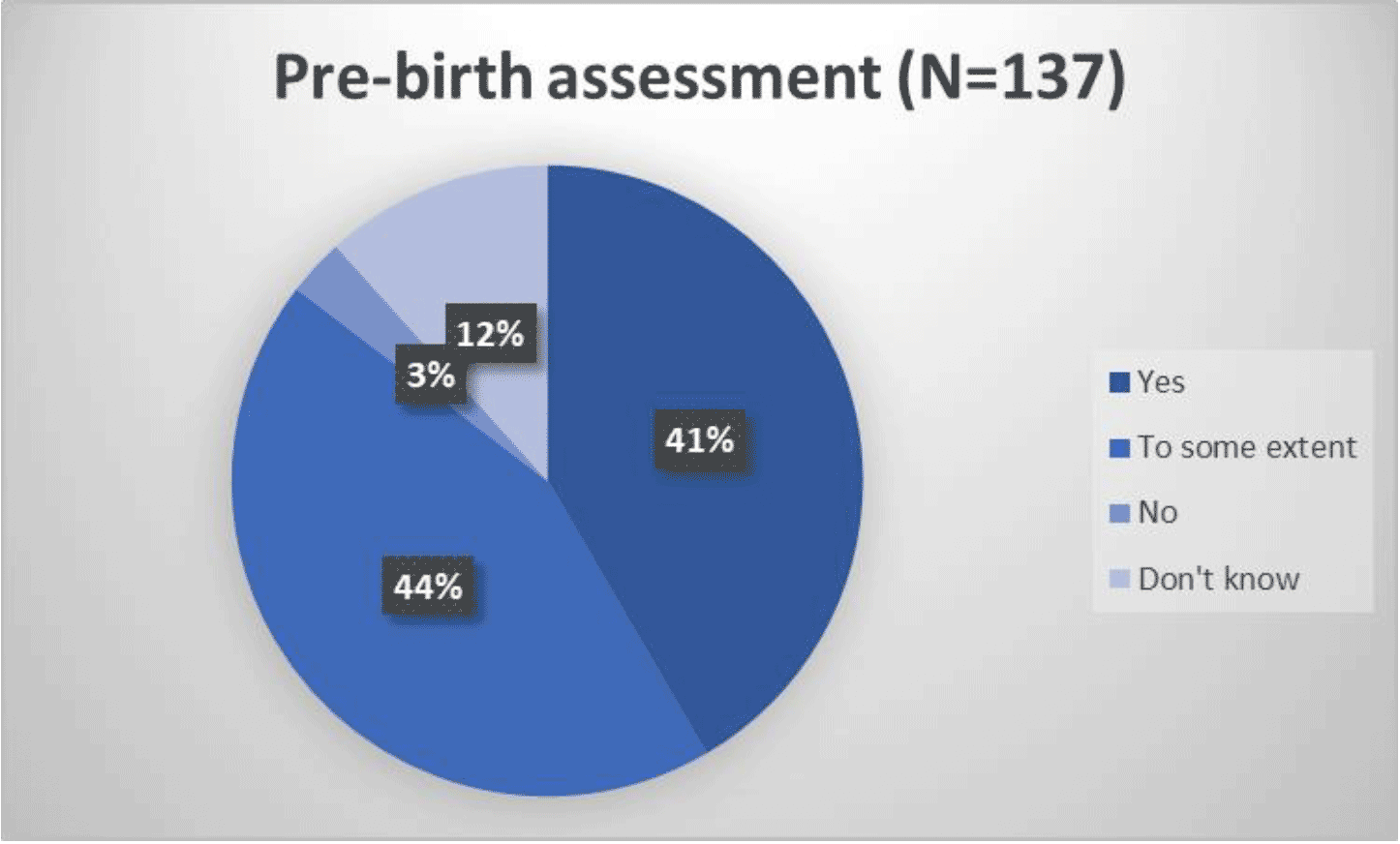

Do these parts of the guidance clearly and fully set out the context and processes?

Stakeholder Event Themes

The main themes raised at the stakeholder events were:

The inclusion of the section on pre-birth assessment and support was welcomed. It was described as covering policy and practice well and as being sensitive to the needs of parents.

The guidance talks about parental behaviours but there is nothing about parental capacity; the focus on a strengths-based approach could be sharpened.

There was support for the focus on earlier intervention, including the suggestion that a pre-birth meeting should be held as soon as possible and not wait for the 28 weeks.

The role of the father could be strengthened.

Recent pathways work undertaken in Forth Valley and Tayside could be featured.

The largest proportion of respondents (44% of those answering the question) thought that the guidance clearly and fully sets out the context and action required to keep an unborn baby safe to some extent.

Around 80 respondents made a further comment at this question.

A number of the comments addressed the interplay between the coverage of pre-birth assessment and support at Parts 3 and 4. While some respondents welcomed the focus on pre-birth assessment and support in Part 4, it was suggested that it also needs to be a clear focus of the child protection processes in Part 3 and throughout the guidance. Some of the comments also referred to Part 2(B) - Approach to Multi-agency assessment in child protection. (Part 2(B) is also the focus of Question 6 above).

Other comments about the structure of the pre-birth coverage within the guidance included that:

- The current coverage in Part 4 should be removed and integrated into Part 3 of the guidance, as part of a widely recognised continuing pathway of intervention, care and protection from pre-birth onwards and as part of a child's journey.

- The adoption of a pre-birth IRD is a significant new development in national guidance which is not currently common practice in many areas. However the first mention is in Part 4 of the document. If the intention is that a pre-birth IRD-process should be universally adopted, it should be referenced in Part 3 where IRD processes are discussed in detail.

Other comments referred to the current Part 3 or Part 4, or to what a combined section (taken from Parts 2(B), 3 and/or 4) should cover. Some respondents also noted that comments raised at Questions 4, 5 or 6 also applied to pre-birth assessment and support.

Specific comments on the current Part 4 included that the reference section is particularly useful.

Current coverage of pre-birth IRDs

While some welcomed the flexibility they saw in the approach to pre-birth IRDs set out, others considered the approach to be overly prescriptive. There was a call for some flexibility to enable well-established, and positively inspected, local practices to continue. It was reported that pre-birth assessment is not a new development and we do not need to start at the beginning. The linked suggested was that the guidance needs to have confidence in current local child protection practice, such as current multi-agency screening of pre-birth cases which is separate from the IRD process. Respondents from local Child Protection Committees were amongst those noting that practice in their own area differs from that outlined in the guidance.

Concerns raised about the current framing of the guidance included that the guidance on the need for an IRD is too prescriptive and could result in women being escalated into services disproportionate to their need. Connected points included that:

- It gives the impression that when a Notification of Concern is received it is a foregone conclusion that a CPPM will be held. However, local experience is that a plan can sometimes be put in place to start to mitigate risks to the unborn baby, even before it is agreed whether or not to initiate a pre-birth assessment.

- There is little reference to support of the type that can divert expectant mothers away from child protection procedures.

- There is a danger that the guidance bureaucratises a process that currently works well and inadvertently may disrupt good practice, resulting in a punitive approach to pre-birth cases.

General approach to covering pre-birth assessment and support

It was acknowledged that the issue around the legal status of child protection work with unborn babies remains highly problematic. It was suggested that the guidance could recognise this complexity and the disadvantage at which this effectively places birth parents - namely that very significant decisions are being reached about the care of the baby at a time when the family have no recourse to legal advice and representation.

In terms of the principles and approach that should underpin the coverage, comments included that it should:

- Highlight the importance of pre-planning and the promotion of relational practice with families. Amplify the importance of being alongside parents, sharing concerns and plans to minimise risk in advance of the baby's birth. Refer to commitments to support to pre-birth families so that children can be cared for by their parents where it is safe to do so, in line with the UNCRC and The Promise.

- Highlight the need to balance strengths-based approaches with the management of risk. Also, remind practitioners to operate from a trauma-informed and trauma-responsive approach when working with families.

- Make a clear link to the GIRFEC process. It was suggested that linking to the pending national GIRFEC practice guidance for unborn planning would be helpful.

- Give greater recognition to the midwifery role and make closer links to Health Guidance.

- Reference domestic abuse, including that during pregnancy risks around domestic abuse and coercive control can increase.

Particular issues or topics that respondents wanted to see covered included:

- A description of all the circumstances which would make an unborn baby and pregnant mother vulnerable.

- Keeping an unborn baby safe in the event the mother is a child – ensuring that the rights of the unborn child and the rights of a mother as a child are both considered.

- The potential of FGDM. It was reported that there is an abundance of practice evidence to support the effectiveness of FGDM during pre-birth assessment and support, and the guidance should reference where family plans, strengths, rights and resources can be applied to safe, appropriate plans and outcomes.

- The 3 point test for Adult Support and Protection.[8]

- The importance of perinatal mental health and the best way to respond to any needs quickly.

- The expectations that practitioners themselves can have by way of supervision and training.

It was also suggested that there could be wider exploration of current good practice.

Parents among those likely to need additional and sustained support

Paragraph 230 of Part 4 identifies types of parents among those likely to need additional and sustained support. Related comments included that:

- Any parent who finds themselves subject to procedures would require space for exploration and support; it was suggested that the guidance should be clear that this offer should be available to all parents and that this could reduce the potential for an adversarial relationship between parents and practitioners.

- The guidance could recommend that intensive, therapeutic preventative family support, which is goal orientated and tailored to the specific needs of the family, should be provided.

Particular groups identified as possibly needing a tailored or specific approach included:

- Parents from island communities. It was reported that in island communities where it is anticipated that a birth will be complicated, or the newborn vulnerable, it is not uncommon for the expectant mother to be flown to Glasgow. This can further challenge planning and in particular timescales.

- Where an expectant mother is in custody.

It was also suggested that the consideration and assessment of parents with learning difficulties needs to be strengthened. It was suggested that this could be achieved by including the potential for utilising specialist disability parenting assessments.

Fathers and extended family

A number of respondents commented on the importance of referencing the role of fathers and/or partners. It was suggested that they should be mentioned earlier, or given more prominence. Specifically, it was suggested that:

- There should be more explicit guidance in relation to the role of fathers in pre-birth assessments, with the protective and/or risk factors clearly and explicitly explored in the assessment.

- This would be best placed directly in the guidance rather than a practice briefing which may be lost if not always read alongside the relevant section in the guidance.

In addition to fathers, it was also suggested that guidance needs to cover the inclusion of extended family members and significant others in a vulnerable pregnant mother's life. It was suggested that recognising extended family members within any support plan developed, to mitigate the need for a newborn child to become looked after, is aligned to the Children and Young People (Scotland) Act 2014 Guidance.

Timescales, including for IRDs

A number of respondents addressed the timing and timescales of different aspects of practice, including in relation to IRDs. A general observation was that the timescales set out within this section require further consultation and clarification. An example given was that the guidance could be interpreted as suggesting that a pre-birth conference could be convened prior to an assessment being completed, but that this may undermine the relational practice approach that should be paramount.

There was a concern about the timescales (as specified in Appendix D of the guidance) for holding an Unborn Child CPPM being as soon as possible, or within 28 days of concern being raised and always within 28 weeks of gestation.

Comments included that the viability of pregnancy should be considered where a concern is raised very early in pregnancy. Where a pregnancy is viable, it was reported that assessments could start earlier, and the option to initiate pre-birth child protection processes at an earlier stage to allow for a longer assessment period should be made clearer. This was seen as particularly important in relation to assessing parenting capacity and capacity to change (a theme at Question 6 and returned to briefly below). Recently published local guidance across Forth Valley and Tayside was highlighted, and it was reported that the Forth Valley Vulnerable Pregnancy Pathway Guidance 2020 notes the need for pre-birth case conferences prior to the 28-week timescale.

It was reported that there may be occasions when the timescales set out in the guidance may not be realistic. Circumstances which were identified as having an impact on timescales included when the pregnancy is made known or disclosed.

There was also a concern that the 28-day timescale could have a negative impact on pre-birth assessments; informed assessments take time and operating under shorter timescales would give little scope for information gathering, meaningful engagement from family and the opportunity to explore areas of concern/risk or to adequately explore family and community supports. It could lead to inaccurate assessments and have a negative impact on the relationship with families that has been established by services.

Other comments included that:

- It would be helpful to cover what happens when the timescales for CPPM within 28 days of concern are not met, including in relation to escalation.

- Clarity on possible exceptions to the 28-day timescale would be helpful. However, another perspective was that no exceptions should be set out and the guidance should instead state that professionals must seek to intervene at the earliest point. It was suggested that where concerns are raised pre-birth, a discharge meeting or any formal child protection meeting taking place post-birth is a reflection of failure on the part of protective services.

Convening an IRD

It was reported that an IRD may not be the appropriate response to concerns for an unborn child – a case discussion or pre-birth meeting is likely to be required. This would generally take place first and a possible outcome of this is an IRD. It was suggested that the guidance should take account of local health board arrangements for pre-birth Assessment.

Other comments focused on both who should trigger an IRD and the circumstances under which an IRD should be triggered. On the latter point, comments included that:

- Greater clarity about the types of concern that would trigger a pre-birth IRD would be helpful. It was acknowledged that the intention might be to cover this in an accompanying practice note.

- There is some inconsistency regarding the threshold at which child protection procedures should be followed with regard to an unborn baby. It suggests when there is risk of harm, whereas in relation to a child it is where there is a risk of significant harm. It is not clear whether this deliberately marks a lower threshold of concern for an unborn baby than for children and young people.

- The guidance could suggest considering co-location of professionals within a "hub" approach, which would greatly improve the service offered to vulnerable parents and children (related issues have been covered further at Question 3 in relation to GIRFEC).

In terms of who could or should convene an IRD, it was noted that the wider coverage of IRDs states that 'the decision to convene an IRD can be made by Police, Health or Social Work, but an IRD may be requested by any agency'. It was noted that an equivalent statement is missing from, but should be included in, the coverage of pre-birth IRDs in Part 4. In this context, the potential role of the Third Sector or Adult Services in early identification of pre-birth child protection concerns was highlighted.

There was a call for more specific guidance on responsibilities within Health to raise an IRD and who can make that decision, for example whether a midwife, family nurse or member of an NHS Child Protection Team?

However, it was also thought that as currently structured the guidance may imply the sole responsibility sits with maternity services. It was suggested that the guidance should describe exactly who can raise a concern about an unborn baby, which should be any practitioner or manager, with an opening message that any agency/practitioner can raise a concern for unborn baby, including any agency/practitioner working with a pregnant woman's partner.

A number of comments specifically addressed pre-discharge meetings, with issues highlighted including that:

- The sections outlining the process for discharge meetings at hospital do not sufficiently emphasise the importance of working with families, and that the suggested approach may lead to stigmatisation of the parent and the baby, which with good relational practice should not be required.

- Where there is a need to have a post-birth hospital meeting involving members of the Core Group, consideration should be given to how best to do this to minimise the stigmatisation of the parents/family. The use of video based group discussions with professionals/family joining remotely should be considered, and the guidance should be amended to highlight this as practice to be considered where necessary.

- Unpaid carers, including young carers, should be included in a pre-discharge meeting if discharge will result in the unpaid carer taking on additional caring responsibilities once the cared for person is home.

Contact

Email: Child_Protection@gov.scot

There is a problem

Thanks for your feedback