National guidance for child protection 2021: consultation report

This report shows the results of the public consultation on the revised national guidance for child protection in Scotland, and our response to the results.

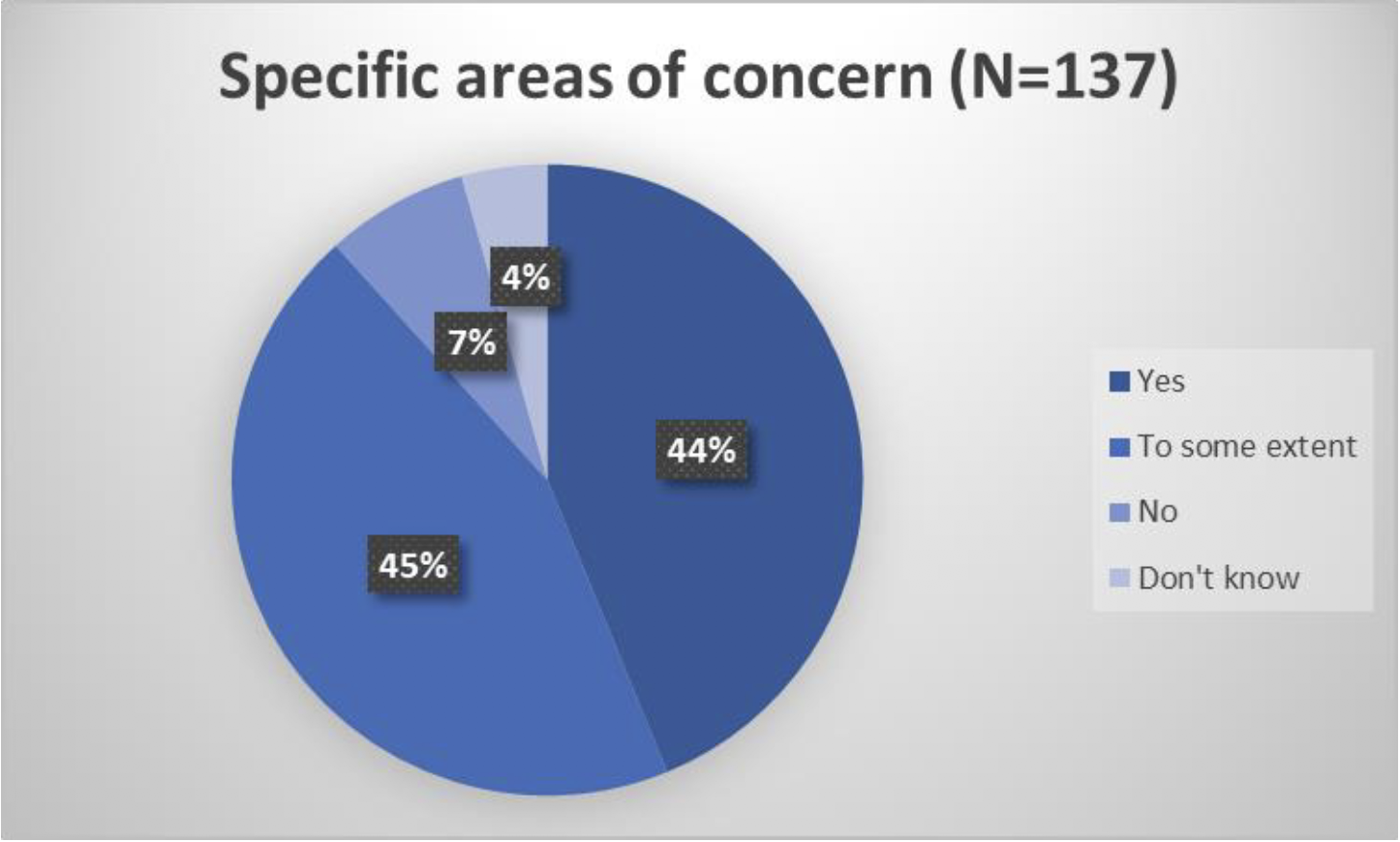

Specific areas of concern

Q11: Specific areas of concern (Part 4)

Do all sections of Part 4 of the National Guidance address the specific areas of concern appropriately?

Stakeholder Event Themes

The main themes raised at the stakeholder events were:

Participants were generally pleased to see the addition of Part 4, including as a good resource for practitioners and professionals working across a range of sectors.

However, there was a concern that if practitioners focus on Part 4 they will miss valuable information in earlier sections (especially Parts 2(B) and 3) on planning and procedures.

The coverage on domestic abuse could be enhanced, either in Part 4 or elsewhere across the guidance

The Children (Equal Protection from Assault) (Scotland) Act. 2019 could be covered.

The largest proportion of respondents (45% of those answering the question) thought that the guidance addresses the specific areas of concern appropriately to some extent.

Part 4: Specific areas of concern – provides guidance on specific forms of abuse and neglect, concerns and circumstances and signposts further resources. It covers pages 129-207 of the draft guidance.

The analysis below begins with some general comments made about Part 4 overall. It then considers points that specifically addressed one of the 38 sections in Part 4. These are ordered according to that of the guidance. Please note that there were no specific comments on some of the sections.

Around 100 respondents made a comment at Question 11.

General comments

There was an initial query as to why the guidance is now referring to 'concerns' rather than 'Specific Circumstances' or 'Indicators of Risk' as in the previous guidance; an explanation would be helpful. The use of language such as 'specific areas of concern' was described as not reflecting a human rights-based approach and as creating the potential for practitioners to believe that parents who represent protected characteristics or who experience situations of vulnerability should be of immediate 'concern' to Children and Families Social Work Services.

Part 4 was sometimes described as useful, helpful or accessible, and there was support for the comprehensive set of issues covered. Although there was some support for a research-based approach having been taken, others thought that while there is some helpful reference to key themes and research, there is insufficient attention to operationalised practice, and how to support practitioners to develop and sustain the competencies for strengths-based child protection practice.

An associated concern was, given that the broad range of issues covered has added significantly to the length of an already lengthy document, there could be a risk that practitioners may focus on the information in Part 4 in relation to a specific area of concern and inadvertently overlook valuable information in earlier sections.

It was suggested that some cross-referencing to Parts 2 and 3 may be required to highlight processes which can support children and young people affected by different issues. Specifically, there could be further linkage with other parts of the guidance, for example those relating ASP, GIRFEC, or Assessment. It was also suggested that highlighting that many families face multiple adversities would be helpful.

Further concerns raised included that elements of Part 4 are repetitive, or that there appears to be an imbalance in the detail provided between different policy areas with some seeming to be given more 'weight' than others; this could be interpreted by practitioners and managers as an unintended weighting of importance.

Other comments or suggestions on the overall layout or range of content included that:

- Whilst accepting that the guidance is not meant to be read sequentially, moving the current Part 4 to before the current Part 3 would help to conceptualise specific areas of concern before the initiating of child protection procedures.

- Some rationale for the order in which the topics are presented in Part 4, and how they are grouped, would be helpful. One suggestion was that the specific concerns should be presented in alphabetical order, based on a lead word (such as obesity). It was also reported that practitioners are very familiar with the term 'Trio of Risk' or 'Toxic Trio' and it was suggested that the order and structure could reflect these links.

- Greater consistency in layout and structure would be helpful. Where the layout is clear in terms of definition, occurrence, impact and response it is easier to read and access. Consistent use of headings, subheadings, bullet points and bold text would further enhance navigation through each topic. The sections should be consistent in their use of underpinning evidence; at present some sections have statistics, references etc, and others do not.

- The graphics used are different to those in other parts of the guidance.

- Cross referencing each topic to legislation would be very helpful.

- There are several examples of outdated language being used, for example: reference to residential placements; children's units; or to Personal and Social Education as opposed to Personal, Social and Health Education.

- Any statistical information used will be out of date almost immediately.

- A number of direct quotes from the Independent Care Review have been used (with some repeated) but the guidance does not always explain the context or the implications for practice.

- Where there is reference to specific frameworks, there should also be a reference to 'or similar local processes'.

- Significant case reviews could be included within the reference lists.

- There should be reference to the NSPCC Learning Case Review Repository.

- It would benefit from the addition of a FAQs section.

- Some of the topics could be covered in practice briefings instead.

Other general observations or comments about Part 4 of the guidance related to trauma and included that it is important to highlight that issues often do not occur in isolation but are likely to add to the risk of harm for children and young people. It was suggested that the impact of trauma should also be acknowledged in relation to many specific circumstances.

Also in relation to trauma, the inclusion throughout the guidance of the need for trauma-informed practice was welcomed, although it was suggested that it could be moved nearer the beginning to help readers better understand what can lead children to needing protection and offer some useful context before readers become immersed in the processes. It was also suggested that some of the references to trauma-informed practice should be strengthened or that certain sections, such as those relating to mental health or disability, place an emphasis on diagnosis which fails to acknowledge that a lot of children being supported through the child protection process do not have a formal Mental Health diagnosis but demonstrate many behaviours linked to trauma.

As noted above, it was also reported that practitioners are very familiar with the term 'Toxic Trio' so including some discussion on the links between domestic abuse, mental ill health and parental alcohol and drug misuse, would be beneficial.

Other overarching comments or suggestions included that:

- It would be beneficial to have concise definitions of each of the specific areas of concern, and ensure these definitions are replicated in the Annual Statistical Return/Data Guidance to enable more accurate data recording. There should be consideration of whether 'areas of concern' not currently recorded should start to be recorded and how this would be done.

- The specific areas of concern could be further strengthened in a child protection context if there was greater prominence given to evidencing 'significant harm' against each concern. This would help frame and distinguish between wellbeing and child protection, which can be a challenge for universal services.

- There should be further emphasis on early intervention and preventative action for children and young people.

- The approach to the Age of Criminal Responsibility (Scotland) Act 2019 (ACRA) in the guidance appears disjointed and there might be a more coherent way of presenting it. Specifically, ACRA is introduced in general terms as part of the section on Children Who Display Harmful Sexual Behaviour, but it pertains to non-sexual offending so its current placing might be misleading. In addition, the key components of ACRA set out need to be revised.

- Strong emphasis should be placed on the need to ensure the views and experiences of children.

- Gathering gender-based issues into one section under this heading may help signal their importance to Chief Officer Groups and other stakeholders

- and enhance strategic responses at a local level.

- The guidance should consider the issues for rural and island communities, with more of an acknowledgement of the differences between rural and island communities and urban areas. One suggestion was to include rurality as a section within the guidance or as a linked practice note. This would give the opportunity to consider further the particular issues of rural poverty or of equitable service delivery.

- There is little or no reference to the Getting our Priorities Right (GOPR) Guidance, the National Framework for Child Protection Learning and Development in Scotland (2012), The National Risk Assessment Framework Model (2012), and the Common Core of Skills, Knowledge and Understanding and Values for The Children's Workforce in Scotland (2012).

Current specific concerns

This section of the report sets out comments made about the specific concerns set out within the guidance and is ordered according to the guidance. There were some of the specific concerns about which no direct comments were made.

Poverty

An initial comment was that poverty needs to be more clearly defined under an all-encompassing definition, explaining the different kinds of poverty people experience in their day-to-day life. It was reported that there are 73 separate references to poverty throughout the guidance and these might be better grouped and linked together under the poverty section.

Comments often focused on issues that could be explored further and/or connections that could be made. It was suggested that the sometimes complicated relationship between poverty and neglect needs to be discussed and defined more clearly. There was also a concern that the section is very research-based and offers less in the way of guidance to assist practitioners to assess the impact of poverty on neglect.

Although there was support for reference to stigma in this section, it was also seen as important not to detract from the focus on attempts to address poverty at a structural level. In addition to reference to stigma, it was also suggested that reference could be made to:

- Shame associated with poverty which marginalises those affected.

- Literacy, mental health issues or learning difficulties as issues that may exacerbate experiences of poverty.

Other issues which respondents thought could be given greater coverage or explored further included:

- The complexity of the impacts of poverty, including intergenerational poverty, on children and families.

- The development of a Social Needs Screening Tool for use across health, education and social care to identify family stress issues which may be related to poverty and social disadvantage in families where a child protection concern has been raised.

- Referral pathways to ensure families potentially suffering from socio-economic disadvantage and stress are enabled to access mitigation and support.

Finally, while the explicit reference to poverty never being a reason for removal from the family was welcomed, an associated note of caution was whether this suggests there is evidence of this happening in current practice, and how poverty has been defined in this context. It was stressed that guidance should support agencies to focus on the impact on and needs of the child regardless of how harm has occurred, offering family support and addressing systemic causes as part of this approach where relevant.

Where services find it hard to engage

Aspects of this section that respondents particularly liked included the change in tone of the language and the emphasis on engagement as a dynamic process that is as much about what professionals bring to the process as the families themselves. It was suggested that the section could be strengthened further by:

- Giving some rationale for why the title of the section has been changed from non-engaging families. It is covered but could be made more explicit.

- Improving the flow of the section with headings to facilitate navigation and demonstrate a logical order.

- Developing the operationalisation of a strengths-based approach to working with families and engaging them in devising and implementing the child's plan.

- Adding guidance on the need for careful consideration of potential stressors for family members during anxiety provoking meetings.

- Addressing working with families with the resources to challenge, and addressing power imbalances created through families' robust articulation of rights, legislation and involvement of solicitors etc.

Protection of disabled children

One suggestion was that this section should be re-ordered and re-framed, setting the protection of children with disabilities within a children's rights framework, and a social model of disability. The use of the term 'disabled' rather than 'children affected by disability' was noted. 'Children with disabilities' was preferred, including because it better reflects that social model of disability.

Other comments focused on definitions and included that the definition of disability should be specific enough for practitioners to work with but not so broad as to include the variety of other vulnerabilities a child might be experiencing. One view was that the use of 'profound' and 'severe' within the definition is unhelpful, including because it is often hidden or undiagnosed disabilities that need child protection responses. It was argued that that the definition and language used in the 2014 guidance is more appropriate.

A slightly different perspective was that describing the more complex end of the needs spectrum may overlook other children with support needs. An example given was that children with developmental language disorder would not typically present as having complex needs but may still require robust collaboration with specialist services to understand their needs and develop personalised approaches to help them to participate effectively.

Other general comments included that:

- There must be greater emphasis to contextualising a child's impairment and/or disability and understanding its interrelationship with other vulnerabilities and experiences.

- The guidance should include a commitment to upholding the highest standards of wellbeing for disabled children, including not having a lower expectation of what 'thriving' would look like for them.

In terms of other aspects that need to be emphasised or covered further, suggestions included:

- There could be more emphasis on communication. Every child should have a voice, including deaf children or families and children or families with vision impairment or sight loss. For example, there is a need for accessible information to be provided in advance of any meeting and for the meeting location to be easily accessible. Consideration should be given to ensuring that the meeting is conducted in an inclusive way. The workforce should seek assistance where they are not confident in understanding impairments and or communication methods and not rely on parents and carers in the context of assessing risk of harm.

- The Principles of Good Transitions should be referenced; transitions is an area where not enough is being done for care leavers and children with disabilities to support these young people in preparing for or making those transitions.

- The complex issue of child protection investigations involving a deaf child should be covered. Deaf children are a highly heterogeneous group whose language and communications needs are impacted by a range of factors. It is important that those undertaking investigations involving deaf children be given additional training or that they seek specialist advice beforehand in order to determine how best to facilitate the deaf child's involvement.

- The guidance should caution against the medicalisation of issues and any focus on the child's impairments in planning meetings.

- Information and links to professional organisations that can provide specific support to families of disabled children and to parents with disabilities should be included.

Parents with learning disabilities

A general point was that the guidance could be strengthened to better reflect best practice around working with parents with learning disabilities or learning needs. This section could be further improved by emphasising the need to get support right for parents with learning disabilities and learning needs in the first instance, from pre-birth onwards.

Other suggestions included that this section should:

- Emphasise that parents will often need ongoing practical and meaningful support from an early stage.

- Highlight the importance of liaising with Community Learning Disability Teams to ensure parents are properly assessed and supported. This will help ensure assessment and support is pitched at a level that parents with learning disabilities can fully understand and engage with.

- Include a reference to advocacy for parents subject to child protection processes. It was also suggested that information should be accessible for parents and additional time allowed for preparation for meetings.

Impact of mental health or health problems on children

A general observation was that this section appears to lack clarity and impact in comparison with sections on other specific areas of concern.

Suggestions included that this section should:

- Provide more on the involvement / partnership working with Adult Mental Health Services, including by making clear that practitioners and others across the workforce may lack knowledge or understanding about how a mental illness impacts on parenting capacity.

- Cover perinatal mental health and the specific considerations and interventions that might be required when this is a concern.

- Offer further guidance around parental mental health and substance misuse. It was noted that there is no reference to Getting Our Priorities Right.

- There were also suggestions for topics that could helpfully be covered in practice notes, including:

- The issue of disabled children potentially acting harmfully to others. It was noted that this is a difficult and sensitive issue that needs to be elaborated on and be framed within a collaborative approach of supporting families rather than removing siblings, as families may be deterred from seeking support due to worries about the implications of doing so.

- Children and young people with Profound and Multiple Learning Disabilities (PMLD). This is important because there is a need for all stakeholders involved in child protection to have a working understanding of children with PMLD and particularly how a child communicates. There have also been situations where a psychiatrist working with a parent has seen or suspects potential neglect and/or abuse/neglect of a child when working with their parent. They lacked the ability to assess parental capacity. Formalising how such situations are resolved would be a positive step.

Children and young people experiencing mental health problems

It was suggested that 'mental and emotional wellbeing', 'mental health problems', 'mental illness' appear to be used interchangeably and that a clearer definition or agreement of what each term means would be beneficial. It was also suggested that the definition of suicide needs unpicking, but without referring to deliberate self-harm, which while still used does generate some debate.

It was noted that the guidance does discuss some of the risk factors associated with mental health, but it was suggested that it could also refer to groups who may be at risk, such as deaf and disabled children.

From a specialist health professional perspective (psychiatry), it was suggested that by defining the sphere of support for children, better and more rounded care for children who fall under the auspices of the guidance would be deliverable. It would also benefit collective decisions made about pursuing child protection cases, ensuring mental health representation to inform decisions.

Suicide and self-harm affecting children

Comments included that this section could be more clearly linked to the preceding sections on mental health. Other suggestions included adding references to:

- The National Suicide Prevention Leadership Group and the Suicide Prevention Action Plan.

- The workforce accessing local training on Mental Health First Aid and safeTALK.

Responding to neglect and emotional abuse

It was suggested that this section is comprehensive and offers support for the focus on neglect and emotional abuse. In terms of aspects that could be given greater emphasis or focus, suggestions included:

- Multi-agency assessment that ensures older children and young people receive immediate and appropriate support.

- Noting that issues may indicate neglect but may alternatively be indicators of other forms of trauma.

Domestic abuse

A number of sometimes extensive comments focused on the domestic abuse section. Although some thought the guidance was helpful, some were also looking for a number of changes or additions.

This included a re-echoing of comments made at earlier questions that the principles of Safe and Together should be fully embedded across the guidance to ensure that children receive a truly joined up response, and that the lack of coherence between criminal, family and child protection systems should be fully addressed. Further comments relating to Safe and Together included that:

- Perpetrators are invisible in the guidance; it must help practitioners to identify perpetrator behaviours', including manipulation and threat, and help them understand that many perpetrators of abuse will be skilled in falsely presenting as caring fathers, or even attempt to present as victims of domestic abuse.

- There should be links to the Model and a summary of the training involved and how to access it.

There was also a call for the guidance to explore patterns of abusive behaviour, and how these impact on child and family functioning, rather than taking an incident-based approach. Specifically, it was thought that stronger emphasis should be placed on children not needing to be a direct witness to abuse for it to impact on them.

It was noted that abuse that does not reach the legal threshold for criminal behaviour may still cause harm to a child, and a child protection response may be required. It was suggested that there should be further exploration about the harm and impact on the child, even where this does not meet the legal threshold for criminal behaviour.

It was also suggested that the guidance would benefit from stronger integration of domestic abuse with a number of other sections and in particular with:

- The neglect and emotional abuse section, where insufficient attention to the dynamics of domestic abuse and particularly coercive control could pose a real risk to women and their children.

- The sections on 'honour-based violence and forced marriage.

There was a particular concern about embedding the principle of partnering with the non-abusive parent, with the guidance described as dangerously weak. An associated point was that some of the language used (for example at paragraph 97) is victim blaming and problematic. There were particular concerns about some of the references to 'choice' made across the section.

There was a call for the guidance to recognise the reasons that make it difficult for women to trust professionals and guide practitioners in creating an environment in which women feel safe to disclose. Another perspective was that the guidance should highlight the importance of partnering with the non-abusive parent to identify why they do not recognise the risk posed by the perpetrator, which will involve an understanding of the pattern or abuse and the impact on the family.

Other suggestions included that:

- There should be further information in relation to coercive control and behaviour laws, and what practitioners can do to support victims and families with regards to this law.

- It is crucial that guidance address the safety risk that child contact poses in domestic abuse cases. This is highlighted in the Children (Scotland) Act 2020, which should be referenced in this section.

- Scottish Government figures show that more women make a homeless application under the category of 'dispute within the household: violent or abusive' than for any other reason. It is important that the guidance recognises this reality and the urgent need for appropriate housing support in order to ensure that women made homeless by domestic abuse are not then subjected to scrutiny for neglect.

- More information is required around harm, cause and impact; the current wording does not adequately reflect or address the reality of the complex, significant impact of domestic abuse on all areas of life for non-abusing parents and children.

- Some discussion of the prevalence of domestic abuse might be useful. Also in relation to data, it was suggested that the incidence data presented must be contextualised in relation to a pattern of ongoing abusive behaviours.

- In relation to references to violence against women and girls, consideration should be given to whether boys should be included.

- The guidance should refer to a gender based perpetrator to reflect same sex abuse and female abuse of male partners.

- There is a missed opportunity to address the unreported issue of male victims of domestic abuse; it is important to contextualise barriers to males and individuals in same sexual relationships reporting domestic abuse.

- The guidance should be more explicit in guiding practitioners to identify and access local gender based violence, and drug and alcohol services. The identification of a single national organisation in the guidance reduces the opportunity for a coordinated approach at the local level. There should also be explicit direction to use locally developed interagency guidelines where relevant.

- There should be reference to the use of Operation Encompass to support children experiencing domestic abuse.

In addition to the section on domestic abuse, it was suggested that the guidance should also include a section on gender equality. Further comments included that:

- To identity potential harms that a child may face - be that by a Social Worker or Practitioner - gender and its role in causing violence must be understood and addressed.

- Primary prevention of violence against women and girls begins with addressing gender equality at all points of interaction with the child, be it at the foundation point of education in the form of gender equal play or in interaction with Child Protection Services.

It was suggested that there must be an acknowledgement that the needs of children of different genders, and the risks they face, are often different due to their gender identity, and other intersecting identities such as class, ethnicity, disability and sexuality. Both GIRFEC and the guidance should strive for a more intersectional approach.

Children and families affected by alcohol and drug use

It was noted that this section refers to substance abuse and suggested that this is stigmatising language that should be avoided.

There was a concern that the approach set out is not fully consistent with national alcohol and drug policy and strategy and that, while appreciating that alcohol and drug use within a family does not inevitably lead to child protection concerns, the overall tone is not consistent with a 'potential for recovery' message. This could lead to significant misalignments of risk assessment from Children's Services and specialist Drug and Alcohol Services, with consequent negative impact on family's engagement with protective interventions.

A whole child approach that does not see a child's vulnerability in isolation was advocated. Specifically, it was noted that we must understand trauma, disability, poverty and family background to understand the child, and substance use is just one part of a child's context.

It was suggested that this section should include coverage on:

- A number of current challenges for drug and alcohol users, particularly in relation to episodes of parental or child Non-Fatal Overdoses (NFODs) and/or Drug Related Deaths (DRDs), providing guidance to practitioners around the risks and the actions that could be taken across partners. Also, the need for robust information sharing around episodes of parental or child NFODs and DRDs.

- The impact of addiction on parents' ability to work with services (i.e. the impact on the brain).

- Issues of risk, such as asking services to hold on to a child even where their behaviour is challenging.

- As above regarding domestic abuse, guiding practitioners to identify local gender based violence, and drug and alcohol services, and explicit direction to use locally developed interagency guidelines.

There was also a call for signposting to better training and development resources, with the online Scottish Drugs Forum training cited as an example. It was suggested that a workforce development approach that looks beyond training to supervision, coaching and sharing of knowledge and awareness between disciplines should be encouraged.

Physical abuse, Equal Protection, and restraint

In addition to welcoming coverage on physical abuse and use of restraint, other comments included that it is important to reflect that this section could also apply to paid caregivers.

With reference to the coverage of the Children (Equal Protection from Assault) (Scotland) Act 2019, it was suggested that more narrative on this legislation would be welcome.

Also in the light of the Children (Equal Protection from Assault) (Scotland) Act 2019, it was suggested that the guidance needs to be revised in terms of the disposal options available to Police Scotland. Specifically, it states that that Police can use informal warnings but this is not a disposal that will be used by Police Officers.

The coverage of restraint was described as useful and as covering the main areas of concern, including by providing a clear view of the negative impact of restraint on children. Further comments and suggestions included:

- It would be clearer if this section were termed 'Trauma responsive approaches in the use of restrictive practices'.

- The Restraint Reduction Standards should be referred to as a minimum, including the need for agencies to be following restraint reduction plans. Also, links and references to the Scottish Network for the Reduction of Restrictive Practices and Scottish Physical Restrain Action Group would be of benefit for practitioners.

- This section could be expanded further, particularly in relation children with a disability. The guidance acknowledges that children with additional support needs are more likely to experience the inappropriate use of restraint. It could be strengthened further by including direct references to the necessity for clear and consistent written agency policies and procedures in relation to restraint, the use of risk assessments and the recording of incidents. These actions are recommended in the No Safe Place: Restraint and Seclusion in Scotland's Schools investigative report published by the Children and Young People's Commissioner for Scotland in 2018.

- The guidance should stipulate the need for debrief and learning as part of the process of recording an event.

When obesity is a cause for escalating concerns about risk of harm

Although welcomed, it was suggested that this section is too vague to be helpful in practice. Queries raised included whether in the case of severe obesity, the expectation and intention is that paediatricians will initiate child protection processes in all cases where a parent refuses to engage with services to tackle a child's obesity? If not, what would the criteria be for taking further action?

It was suggested that more clarity would help to promote consistency of practice across the country.

Child Sexual Abuse

It was reported that the identification of sexually abused children by child protection systems in Scotland and the UK remains very low, and even appears to be decreasing. It was suggested that the guidance needs to acknowledge this; it is not enough to explain the dynamics of child sexual abuse, the feelings of children or the effects, welcome as these sympathetic explanations are. There was a call for the guidance to offer practitioners actual pathways to improvement.

Both in this section and that below (child sexual exploitation), it was suggested that use of language should be explored. Specifically, it was suggested that the language used: attributes concept of vulnerability and power; describes the relationship between 'abusers' and 'abused'; and influences perceptions of victims.

In terms of other suggested additions or changes comments included that the guidance should:

- Make clear that all children who have experienced sexual offences have experienced significant harm.

- Name any false assumptions which have prevented professionals acting or talking to children about possible sexual abuse. The guidance should clarify which assumptions are mistaken or inappropriate.

- Explain that most children do not disclose needs and what professionals and others may, therefore, actually do to protect children when they suspect child sexual abuse.

- Cover undertaking emotional needs assessments and accessing therapeutic support following the discovery or disclosure of child sexual abuse.

- Offer models for productive longer-term assessment, which is vital given everything we know about the silencing of children, and the long time they often take to disclose.

- Reference the development of the Barnahus standards in Scotland, which would support future development of practice.

- Give sufficient attention to contextual safeguarding and the protective, observant roles of communities, especially given evolving initiatives on contextual safeguarding.

- Highlight the link between domestic abuse between young people and sexual violence in these relationships.

Child sexual exploitation

As with reference to child sexual abuse, there was a call for practitioners to be offered guidance on actual pathways to improvement in identifying child sexual exploitation, with many of the suggested changes to the section on child sexual abuse also considered appropriate to this section.

While specific mention of child sexual exploitation and child criminal exploitation (covered in its own section at Page 183 of the guidance) was welcomed, it was suggested that widening the definition to child exploitation would capture all instances where a child is exploited, whether it be for sexual purposes, people trafficking, county lines or any other form of exploitation.

References to contextual safeguarding were also welcomed, but here and elsewhere it was suggested there should be a greater focus on promoting the approach. There was a call for greater collaborative working between agencies and communities to target the places where children are harmed and the people that harm them; there should also be further information within the guidance to support practitioners – and children, young people, carers and parents – where there is a concern about the risk of a child experiencing sexual exploitation.

Other comments included that there is no mention of the Fraser Guidelines or Gillick Competencies used by sexual health services as part of their assessments.

Indecent images and internet-enabled sexual offending by adults

The complexity relating to assessing risk of harm in the context of indecent images of children was recognised, but it was suggested that this section is quite basic given that complexity. In particular, there was a concern that the section on inappropriate images appears to be minimising the issue, particularly as it references literature which suggests that some offenders are at low risk of future offending or progressing to more serious offences. Further points included that:

- The statement 'Some parents who have no criminal history who are arrested for downloading IIOC may have provided their children with positive parenting', may be partly true, but it should not be implied that this type of offence can or should be separated from parenting.

- It is important not to minimise the harm and distress caused by those viewing indecent images of children. The section could be enhanced by adding the need to recognise the impact this can have on individuals and families.

- The focus on assisting practitioners and managers to assess risk of contact offences means risking failing to recognise the seriousness of these offences in and of themselves.

Suggestions included that the section should:

- Be more explicit about evidence around contact/non-contact offences.

- Note that non-contact sexual offending can have equivalent impact to contact offending or may be the beginning of the journey into contact offending.

It was also suggested that practitioners – especially teachers and youth workers – would welcome guidance on how to deal with incidents of youth produced sexual imagery.

Children and young people who display harmful sexual behaviour

It was noted that there is a clear distinction made with children over and under 12 years of age in the Serious harmful behaviour shown by children above and below age 12 section (13 sections below within the guidance) but not in this section; the rationale for this difference was considered to be unclear.

Also with reference to these two sections, it suggested that there is some overlap and duplication which could be reduced if they were combined or located sequentially within the guidance and cross referenced.

Finally, it was noted that while there is a child-focused ethos to this section, it would be appropriate for the guidance to acknowledge that there remains a requirement for Police to investigate a crime, both before and post-ACRA implementation.

Child protection in the digital environment/online safety

It was suggested that this section could be enhanced, with specific suggestions including:

- Expanding the definition of forms of online abuse, as it currently focuses on abuse directed towards a child and perpetrated by someone else, but does not include, for example, criminal exploitation, online privacy, cybersecurity or data violation, such as oversharing.

- Considering harms that may result from neglect, or for which there is no clear perpetrator, such as accessing inappropriate content online, gaming disorder or where children abuse others online.

- Referencing prevention and education for children.

Under age sexual activity

It was suggested that the guidance should:

- Make clear that sexual activity under age 13 is always illegal and should always be a matter for a child protection investigation.

- Include an explicit reminder that a pattern of sexual activity, sexually transmitted infections and pregnancy in under-16s is very frequently linked with a background of Child Sexual Abuse and Child Sexual Exploitation and should always bring concerned curiosity and gentle questioning of the young person. Sexual abuse and exploitation bring sexual signs.

Children who are looked after away from home

General comments about this section included that it should:

- Make distinctions about parental rights for the child. Kinship carers and adopters who legally have parental rights should be treated the same as birth parents. Those who do not have parental rights should be risk assessed and appropriate action taken.

- Stress the importance of appropriate preparation, checks, assessment and review as well as training and carer support plans, all of which help protect children from harm.

- Acknowledge the need for safe caring within other care settings such as kinship and residential care, and how this can be achieved through discussion and supervision.

- Cover allegations within residential establishments and adoptive placements, including giving clarity and detail for practitioners on the protocols for allegations against kinship carers and adopters.

- Address where there are ongoing child protection concerns about children in family placement settings and provide guidance on this issue.

- Recognise and include the increase in formal kinship care placements and the development of specialist Kinship Teams. The Service Manager for Kinship Care should also be referenced as being notified of any child protection concerns.

It was also suggested that further guidance on cross border issues, in terms of protection and placements in different parts of the UK, would be useful, in particular on the topic of linking to previous reviews in different local authorities.

Preventing repeat removal of children

A general observation was that this section requires further detail. It was also suggested that it appears to be drawn from the parent's perspective rather than the child's, and that a child's experience should be presented. It was also suggested that this section could helpfully make reference to fathers and their shared responsibilities.

Other suggestions included:

- Using the word 'parent' rather than mother or father here and throughout the guidance.

- The section pertaining to permanence needs to include long-term fostering and informal kinship arrangements.

Protecting unaccompanied asylum-seeking and trafficked children

The section was welcomed, and it was seen as important that the guidance reflects a rights-based approach to protecting unaccompanied and separated children to guide practitioners through a complex legal landscape of devolved and reserved legislation.

Suggestions included that there should be reference to the Scottish Government's own Age Assessment Practice Guidance for Scotland.

Children and young people who are missing

General comments included that there is an inference that professionals should withdraw from families who are difficult to work with, but no suggestions of next steps. Other comments or suggestions included that:

- More specific guidance about home schooling, and how to address the loophole when agencies have concerns about neglect they cannot monitor, would be welcome.

- The guidance should address the child missing in education loophole for independent school students.

- Reference to children 'educated at home' should be clarified to highlight that this section relates to children who are 'formally home educated and withdrawn from authority provision' as many children are being educated at home currently due to the pandemic.

- Child Missing From Known Address is an NHS process for tracing missing children where there are child protection concerns. The process was included in the 'Pink Book' and should also be included in the guidance.

Child trafficking and criminal exploitation

This section was described as informative and as helpfully highlighting links between Serious and Organised Crime and child protection.

As above, it was suggested that widening the definition to child exploitation would capture all instances where a child is exploited, whether it be for sexual purposes, people trafficking, county lines or any other form of exploitation.

In terms of this section, it was suggested that child trafficking and criminal exploitation should form different sections.

Other comments included that:

- More information and guidance on cuckooing and age assessments would be welcome.

- With regards to the presumption of age, where a potential victim of trafficking claims to be under 18 years old and it is clearly obvious that they are not, it would be useful to include advice on how to proceed in these circumstances.

- There should perhaps be reference to the new Police system of Child Protection Registrations on the Police database.

Protection in transitional phases

It was suggested that the guidance articulates well that transition planning should be a robust and facilitative process which develops joint planning arrangements, and if necessary, dispute negotiations between Child and Adult Services to ensure the correct support plan, well in advance of the young person reaching the age of transition.

Suggestions for making this section stronger included:

- Capturing national best practice. It was noted that there is reference to the Public Bodies (Joint Working) (Scotland) Act 2014, but there is limited commentary about the impact and opportunity inherent within integrated arrangements across Scotland, and consequently the section does not highlight and promote where best practice is occurring.

- Having a sharper focus on corporate parenting responsibilities, and the protection of 16- and 17-year olds with strengthened links to adult support and protection legislation and policy.

- Clarifying GIRFEC responsibilities in relation to young people 'in transition' i.e. 16- and 17-year olds who are not in education.

- Providing guidance around transitions between care placements, especially where there are different systems between local authorities, or cross-border authorities to ensure consistency.

Bullying

It was reported that online bullying can involve a much wider range of behaviours than those described, for example involving fake accounts, doxxing and baiting.

Vulnerability to being drawn into terrorism

Although it was recognised that the PREVENT section is reserved text, it was also suggested that more detail would be welcome if that were possible.

Fabricated or Induced Illness

There was a concern that the wording seems to suggest that there are clear signs relating to Fabricated or Induced Illness (FII) being suspected, and that identification is straightforward. However, it was suggested that this is not likely to be the case and that when the child has disabilities that may inhibit communication, identification may be even more challenging.

It was suggested that a link needs to be made to new Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health guidance (awaited) and it should be emphasised that, although rare, certain FII has high risk of death.

A further issue raised was that the purpose of this section, and how it would relate to practice, is not clear. Specifically, it is not clear what practitioners are expected to do with the information set out in respect of a child protection concern.

Other content suggested included a caution that women who believe partners, especially ex-partners, have sexually abused their children, and have raised questions about signs and symptoms have often been accused by practitioners and in the courts of fabricating these, and of Munchausen's syndrome by proxy. Research has shown a pattern of then losing their children to partners subsequently shown to be abusive.

It was suggested that the guidance should remind practitioners that it is important to approach such allegations with as open a mind as they would allegations from any other person. A gender-informed approach should be taken, as it should be taken in all social work. Any reported signs and symptoms in the child should be investigated by specialists in the physical, psychological and verbal signs of sexual abuse in children.

Sudden unexpected death in infants and children

It was suggested that coverage of the crucial role of health within this process could be enhanced, including by recognising the NHS teams with SUDI responsibilities.

Cultural and faith communities

It was suggested that this section could refer to the importance of appropriate levels of supervision for those working with children/vulnerable adults and/or those who have a specific safeguarding function.

Historical (non-recent) reports of abuse

There was a suggestion that this section should highlight that individual institutions may offer support to victims and survivors reporting non-recent abuse.

Other sections required

There were also suggestions about other specific concerns that should be included within Part 4 (or possibly elsewhere or across the guidance).

Transitions was a frequently raised issue, and it was suggested that Part 4 may be a suitable place to include a section with a specific focus on this issue. Coverage could include strengthened links to adult services and support, linked with corporate parenting responsibilities, legislation and policy. Specifically, there could be coverage on transitions, consent and learning disabilities. Also, further expansion on how links can be made into adult protection policies, legislation and services.

Other suggestions included:

- Risk, or specifically Care and Risk Management (CARM). The National Risk Assessment Framework could be referenced, once refreshed, and this would support a universal approach. Also, a greater focus and steer on both the varying assessment tools for children presenting a significant risk of harm to themselves and others and a more consistent a child-led approach to CARM.

- Gender equality (see section on domestic abuse above).

- Equal standards of parenting. There is an issue generally around gender neutral language in relation to parenting which fails to acknowledge the differential expectations that we have for mothers and fathers in relation to child welfare. The guidance would benefit from a section which specifically calls on practitioners to ensure that there are equal standards of parenting for both mothers and fathers, with a recognition that childcare is often seen to be the remit of mothers in our society.

- Drug and alcohol use by children and young people.

- Practitioner resources to support The Children (Equal Protection from Assault) Scotland) Act 2019.

- Sibling abuse, and specifically sibling sexual abuse. Referencing back to CARM (as above), it was noted that there is no reference to sibling, child to child abuse and the assessment of risk and interfamilial factors multi-agency professionals should consider when assessing this.

- Peer-on-peer abuse.

- Child to Parent Abuse and the interface with child protection.

- Neglect in affluent families.

- Religious and/or spiritual abuse.

- Concealed pregnancy and the risk this poses to the unborn baby.

- Aspects of childrens', young peoples' and adults' speech, language and communication, and actions all services should take to implement communication inclusive approaches.

- Dental neglect, and the roles and responsibilities of dentists.

- Sports, sports organisation and organised activities. Further suggestions included information for community groups and sports organisations, including on child protection in sport.

- Allegations against professionals who work or volunteer with children.

- The impact of the COVID-19 crisis, including the need for equitable access to high quality support services to help children recover from the trauma of lockdown and the pandemic.

- The impact of leaving the European Union (EU). Legislative developments due to the UK leaving the EU may have an impact in a child protection context in Scotland. These changes and any challenges should be outlined.

Groups that respondents suggested should be covered included:

- Young carers. It was considered surprising that there are only a few references to young carers, and a short section, which could include information about young carers' right to a Young Carer Statement and support under the Carers (Scotland) Act 2016 and how this differs from the Child's Plan, would be welcome. A further suggestion was that it is important to reference the needs of young carers who may be caring for siblings.

- Travelling families. Specifically, travellers' rights and leaving school early.

- Children (in families) with no recourse to public funds.

- The particular needs of trans children or those who identify as LGBTQIA+. It was suggested that the guidance could make connections to being more likely to experience domestic abuse, substance use, experience mental health issues, stigma or homelessness.

- Children affected by parental imprisonment.

- Children detained in secure accommodation or prison, including use of restraint.

- Children experiencing homelessness.

- Children (16- and 17-year-olds) in the Armed Forces.

- Parents with relapsing and remitting mental illness such as Schizophrenia or Bipolar Disorder.

Contact

Email: Child_Protection@gov.scot

There is a problem

Thanks for your feedback