New Build Heat Standard 2024: business and regulatory impact assessment

Business and regulatory impact assessment (BRIA) in consideration of the introduction of the New Build Heat Standard (NBHS). Looking in detail at the economic impacts of moving to Zero Direct Emissions heating systems in all new buildings.

5. Sectors and Groups Affected

5.1 Local Authorities

42. The NBHS would require amendments to published material forming the Building (Scotland) Regulations 2004 and modification of the supporting guidance given within the Technical Handbooks that support said regulations. As the principal enforcers of the building standards as set out in the Building (Scotland) Act 2003, local authorities will be responsible for scrutinising building warrant requests prior to approval, as well as for completion certificates. Alongside enforcement, local authorities would also be responsible for sanctioning and monitoring.

43. A total of 8 local authorities submitted a response to the second consultation on the NBHS. When including the initial scoping consultation, a total of 18 responses were received from 16 unique local authorities. A full list of the 32 local authorities and whether or not they responded to at least one of the two public consultations is available in Section 19.1.

44. The initial scoping consultation responses from local authorities indicated that:

- A small number of local authorities suggested the proposed timescale was challenging;

- A need was identified to integrate the Standard within existing Building Standard arrangements; and

- There was a need to ensure consumer understanding of the technology options available and how to operate new heating systems.

45. From the second consultation, it was found from among the responding local authorities that:

- All agreed with the proposed approach to regulate DEH systems in new buildings;

- However, 90% indicated there could be unintended consequences;

- Responses as to whether bioenergy may be needed were mixed – 42% thought there would be specific situations for bioenergy systems, 25% did not, and 33% were unsure. The most common theme was for rural communities to be exempt from a prohibition on bioenergy technologies. Further details regarding the treatment of bioenergy as part of these regulations are contained within paragraphs 59 to 64 below;

- 73% of local authorities agreed with the approach to conversions, but almost all (91%) indicated there could be unintended consequences; and

- Most (70%) could anticipate some eventualities where DEH systems in non-domestic buildings could be required.

5.2 Consumers

5.2.1 Quality considerations

46. A risk of the standard which was raised during our SFIT discussions with businesses was the potential for exploitation of consumers when it comes to poor installations of ZDEH technologies. In turn, poor standards could lead to public backlash against the NBHS or the heat transition as a whole through word-of-mouth. The Scottish Government has sought to establish a quality assurance policy framework for mitigating these cases, with actions being taken laid out in our Heat in Buildings Strategy Quality Assurance Policy Statement (QAPS).[42] This risk is further mitigated in new buildings, as any heating or cooling system installed is required to be commissioned and inspected on completion, regardless of technology type.

47. Furthermore, an obligation already exists for written information to be provided to the building owner or occupier regarding the operation and maintenance of the building services and energy supply system. This also includes a Quick Start Guide, which should assist the homeowner in identifying "all installed building services, the location of controls and identifying how systems should be used for optimum efficiency."[43]

5.2.2 Costs

48. With regard to capital costs, the average price for a new-build residential property in Scotland was £253,445 in Financial Year (FY) 2021/22.[44] If the cost of a typical gas boiler including labour and ancillary components were £6,723 and the cost of a typical air-source heat pump £15,148 (see Section 19.3), then the net capital cost to the typical new-build household – assuming the costs are passed on in a 1-to-1 manner – would be around £8,425 or an extra 3%. Note that the technology costs exclude Value Added Tax (VAT), and the cost differential may be more or less than £8,425 depending on the design and specification of the system, as well as prevailing market conditions.

49. Responses to both public consultations highlighted concerns with regard to the impact of this Standard on fuel poverty rates across Scotland. Fuel poverty in homes will fundamentally depend on (i) individual households' costs to heat their homes to meet a defined heating regime,[45] (ii) their incomes after housing costs, and (iii) the appropriate minimum income standard. The first of these will depend on a variety of factors such as the design and quality of the heating system, user operation, the energy efficiency of the property, and prevailing market prices for energy.[46], [47] For these reasons, as well as the fact that new-builds will be built to a high degree of fabric efficiency and – from the perspective of today – do not yet exist, we cannot quantify the impact this Standard will have on fuel poverty. The accompanying Fairer Scotland Duty Assessment (FSDA) explores fuel poverty impacts, and wider socioeconomic considerations, further.[48]

50. It is important to note that fuel poverty is based on the energy required to meet a household's heating regime and not a household's actual energy consumption. As many fuel poor households will implement coping mechanisms such as self-rationing, wearing extra layers, or simply bearing the cold,[49] their actual metered energy consumption can be lower than that which would be required to meet their heating regime.

51. Related to fuel poverty is the question of running costs. It is our view that it is not possible to say definitively whether running costs would be higher or lower than under a counterfactual wherein a gas boiler is adopted. As is explained above, the cost to an individual household to heat their home will depend on a variety of factors, one of which is the prevailing retail prices of gas and electricity.[50] Figure 3 and Figure 4 below highlight the degree of uncertainty surrounding both of these prices in the residential market.

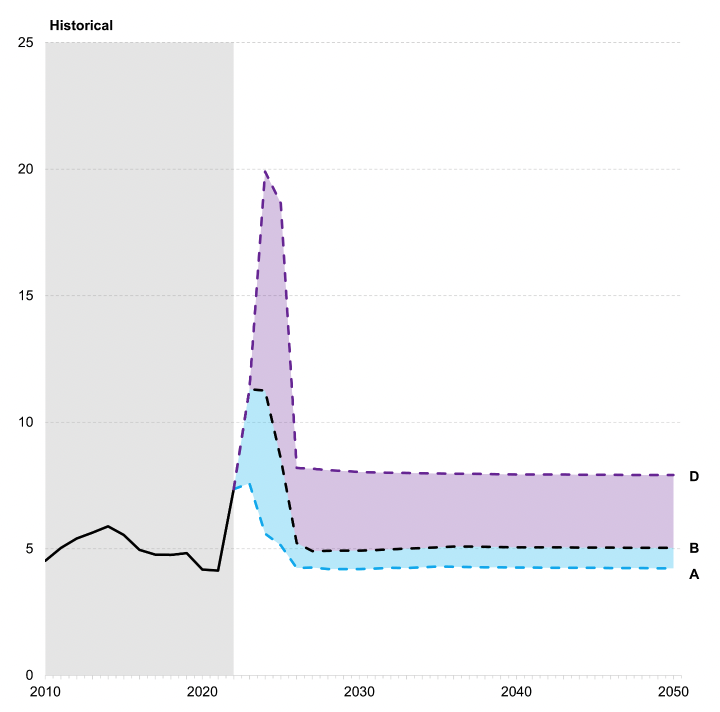

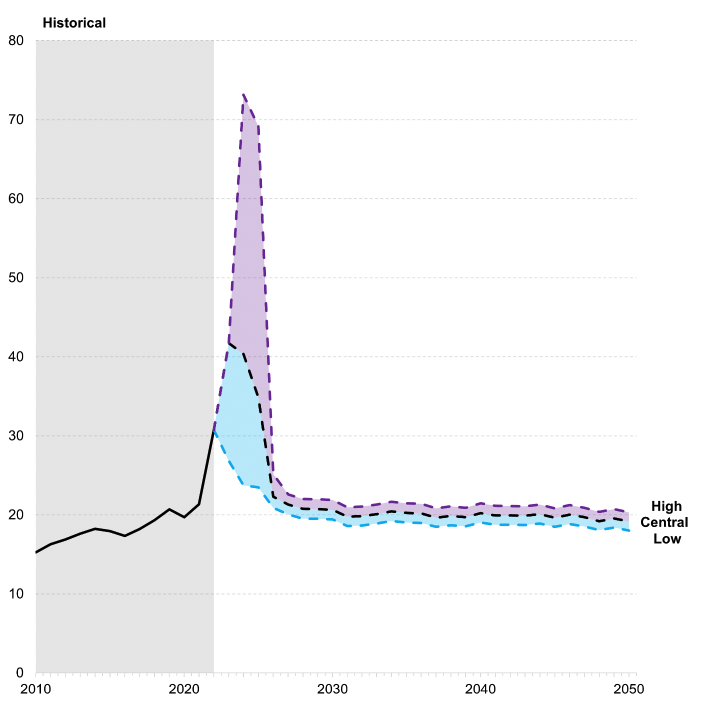

Notes: Based on Department for Energy Security and Net Zero (DESNZ) (April 2023), Data Table 5.[51] Excludes scenario C.

Notes: Based on DESNZ (April 2023), Data Table 4.[52]

52. Taking a simple approach to looking at this problem, whether one would see their energy bill rise when moving from a gas boiler to a heat pump depends on (i) the relative efficiencies from the two systems, and (ii) the relative difference in retail price for electricity versus that of gas. Secondary factors include an assumption that those on a heat pump could avoid reliance on gas, and hence a gas standing charge.

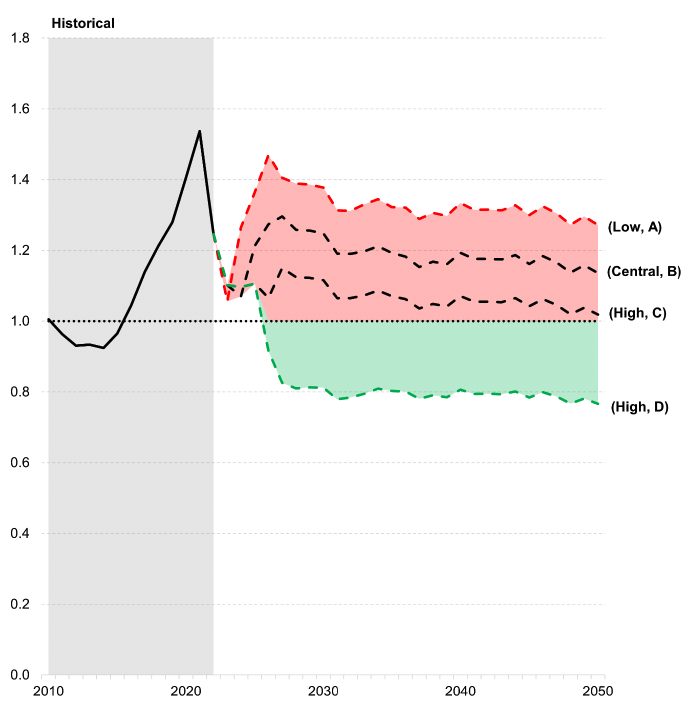

53. Taking into consideration both (i) and (ii) above, Figure 5 below plots the ratio of the effective electricity retail unit price to the effective gas retail unit price in the residential sector over time, using values under different scenarios provided by the Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy (BEIS) as part of the Green Book.[53] It should be noted that the effective electricity unit price is assumed to be obtained using a heat pump operating with a coefficient of performance of 3. In interpreting the graph, a ratio strictly above 1 (i.e. parity) would suggest that the effective unit price of electricity exceeds that of gas, and one would experience a rise in their energy bill when moving from a gas boiler to an electric heat pump, all other factors held constant.[54] Likewise, a ratio strictly below 1 would imply savings on their energy bill. As is clearly illustrated, the range of ratios sits on both sides of parity from 2026 onward, so we cannot definitively say whether running costs will rise or fall in the medium- to long-run.

54. At the moment (April to June 2023), under the Energy Price Guarantee, the effective ratio sits at around 0.95 to 0.96,[55] implying that a heat pump operating with a coefficient of 3 would be marginally cost-advantageous relative to a gas boiler with regard to fuel costs. However, the unit rates available under the Energy Price Guarantee are due to change 1 July 2023, as per the latest Spring Budget.[56] Furthermore, professional forecasters are anticipating the Default Tariff Cap for Q3 and Q4 of 2023 coming in under the Energy Price Guarantee,[57] suggesting the unit rates under that Cap – set by Ofgem – would become dominant in determining the ratio. As such, the ratio may change come summer.

Notes: Based on DESNZ (April 2023), Data Tables 4 and 5.[58] Comparisons take form (W, Z), where W is electricity price (Low, Central, High) and Z is gas price (A, B, C, D). Assumed gas boiler efficiency of 89.5 and heat pump coefficient of 3.0.

55. Though not the same thing as retail energy prices, the social appraisal carried out as part of this impact assessment does quantify the Standard's effect on energy savings using Long-Run Variable Costs (LRVCs).[59] As will be shown in Section 17, whether the Standard has a net beneficial effect for energy costs (reducing them) depends on future gas prices.

56. It is important to point out that the comparison of electricity and gas prices above takes into account UK Government policies as of January 2023. Since then, the UK Government has committed to rebalancing electricity and gas prices by the end of 2023-24 as part of their Powering Up Britain plans, published March 2023.[60] This could result in the narrowing of the large disparity in the unit costs of electricity and gas, which may improve the competitiveness of highly efficient electric heating technologies such as heat pumps when it comes to running costs, and thus their attractiveness.[61], [62]

5.2.3 Compliance with future Heat in Buildings Standard

57. Previous research undertaken by Currie & Brown and AECOM on behalf of the CCC explored the potential costs of fitting ZDEH systems in new-build properties, both domestic and non-domestic, at point of construction versus later via retrofit.[63]

58. The above research concluded that retrofitting new homes with ZDEH technologies and higher fabric standards could cost three to five times more than at the outset. For non-domestic buildings, "the costs of achieving higher standards via retrofit is between approximately 3 and 10 times the costs of delivering them in the new building" (page 78). A caveat to the findings is that they compare the nominal undiscounted costs in 2020 and 2030 to one another.

5.2.4 Treatment of bioenergy

59. The Part II consultation sought views on the following two questions:

- (Question 3) Are there any limited, specific situations where the use of bioenergy systems would be required in new buildings?

- (Question 4) If 'Yes', what do you believe the criteria should be for introducing such an exemption? Please provide evidence to support your answer.

60. Similar to the pattern identified amongst local authorities (as detailed in paragraph 45 above) independent analysis of consultation responses found that views on bioenergy were split: 23% believed there would be no specific situations where bioenergy systems would be required in new buildings, 35% believed there would be, while 42% of respondents to this question were unsure.

61. Of those who answered 'Yes' to Question 3 above, the most common theme was an 'ask' for exemptions for rural and off-grid areas. This was, predominantly, due to a perceived lack of robustness of the energy networks in these areas, and to provide an emergency back-up where supplies were at risk from events such as Storm Arwen. The analysis found that this was raised by a diverse range of stakeholder groups encompassing individuals, local authorities, property developers, and others. Concerns were also raised regarding the prohibition of sustainable bioenergy, in particular, by respondents.

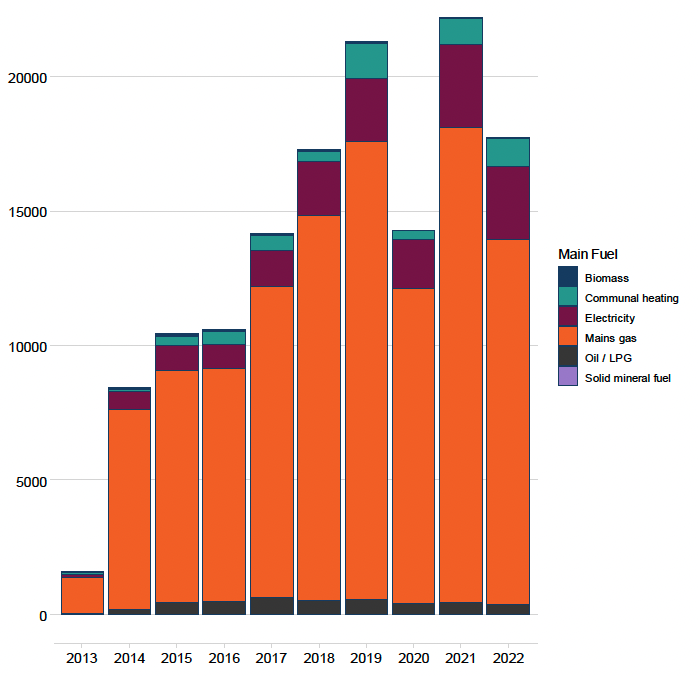

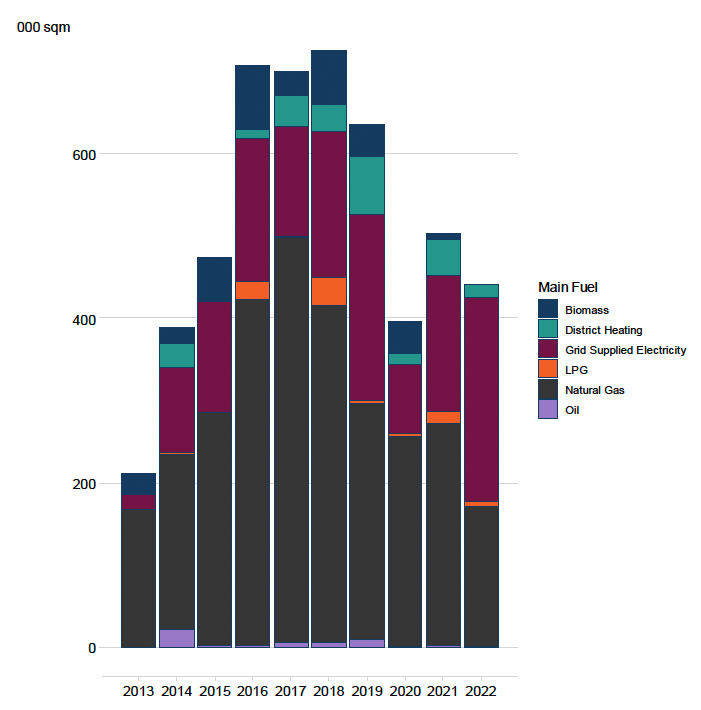

62. As Figure 6 below shows, the number of new-build homes using biomass as their main heating fuel is small, with the total number constructed over the past 12 years – for which we have valid EPCs – being approximately 510. This compares with a total of approximately 16,040 new-build homes constructed with electricity as their main fuel type, and a further approximately 5,540 with communal heating arrangements, constructed over the same timeframe. For further context, over 112,000 were constructed with mains gas as their main fuel type over the same timeframe. Figure 7 shows similar information but for the non-domestic stock.

Notes: Data on each current record held on the Scottish EPC Register from Q1 2013 to Q3 2022.[64] Number of EPCs does not match National Statistics for new housing published by the Scottish Government.[65]

63. If we broaden the scope to count all domestic properties that have adopted wood as either their (i) main heating system, (ii) secondary heating system, or (iii) hot water system, then the number rises to a total of approximately 6,100 properties over the past 12 years, or just over 4% of all domestic new-build EPCs lodged with the SEPCR.

Notes: New-build non-domestic EPCs identified based on purpose listed for assessment being carried out, namely 'Mandatory issue (Property on construction)'. Floor area used rather than individual EPCs on the basis of the non-domestic stock's high degree of heterogeneity.

64. Having considered the consultation feedback, it is proposed that the NBHS regulations will not extend to the provision of any "emergency heating" source. In the context of the regulations, this relates to any fixed combustion appliance installation which is installed to be used only in the event of the failure of the heating or hot water service system, which is designed and installed for use during normal operation of the building. It is envisaged that the accompanying technical guidance will detail the limitations around this provision. Further, heat networks and communal heating are considered 'zero-rated' within the content of the Standard and, therefore, not subject to the DEH system definition.

5.3 Businesses

5.3.1 Mortgage market

65. The mortgage market is seeing strong overarching drivers to accelerate the growth of expanded green financial products available to homeowners and these include: the UK Taxonomy to promote green sustainable investing,[66] the UK Government's consultation on improving home energy efficiency through lenders,[67] as well as the European Energy Efficiency Mortgage Initiative (EEMI) [68] which seeks to support the transition to green mortgages through a greener, more sustainability-focused means of buying, renovating, and living in homes.

66. Further, environmental, social, and governance (ESG) investing has created a set of standards for a company's behaviour used by socially conscious investors to screen potential investments. Environmental criteria consider how a company safeguards the environment, including corporate policies addressing climate change. As part of the Edinburgh Reforms in December 2022, the UK Government committed to ensuring improved transparency and good conduct in the ESG ratings market, and HM Treasury is currently consulting on a potential regulatory regime for their providers.[69]

67. The regulations will create 'green' domestic properties, which are likely to be well supported by the mortgage industry as it will contribute to their own drive to become more environmentally sustainable businesses.

5.3.2 Property market

68. As the sale price of a new building is determined by individual developers and takes into account a range of variables related to building construction costs and local housing markets, it is difficult to quantify the impact that the introduction of these regulations may have on the Scottish property market.

69. The new-build residential property market was valued at £3.3 billion in FY 2021/22 compared to £22.2 billion for the residential market as a whole.[70] Furthermore, new-build residential sales accounted for almost 11% of the 110,248 residential property sales observed in 2021/22. Official statistics for new-build non-residential sales are not available, but the non-residential market as a whole was valued at £4.3 billion in FY 2021/22.[71] Of this, 77% (£3.3 bn) comprised commercial sales. Given the small size of the new-build market in both value and sales terms, we may expect limited direct impact on the property market as a result of these regulations, though cannot rule out indirect spill-over effects.

70. In interviews conducted by Scottish Government officials during the second consultation period as part of the Scottish Firms Impact Test, a range of different business types – including housing developers of various sizes – were asked for their views regarding potential market responses to the introduction of the NBHS regulations. Participants were asked the following two questions:

- (Question 13) Do you envisage any increase in costs relating to the use of ZDEH systems would be passed onto buyers, or would your organisation expect to absorb these costs?

- (Question 14) Do you envisage the introduction of the NBHS having any impact on the supply of housing across Scotland?

71. The majority of respondents (8) to Question 13 believed that costs would be passed onto consumers, while a minority of respondents were of the view that costs may be absorbed by developers. While responses to Question 14 varied, no participants definitively said 'Yes', while 4 said 'No'. The remaining 8 were uncertain.

5.3.3 Heating, Ventilation and Cooling (HVAC) market

72. There are currently almost 4,700 businesses listed on the Gas Safe Register in Scotland, with just over 8,700 registered engineers qualified to work on boilers.[72] It is also estimated that there are 500 heat pump installers currently in Scotland,[73] potentially with some degree of overlap with the Gas Safe registered engineers. It would be expected that those existing DEH installers unfamiliar with ZDEH technologies would require retraining. Support for this is laid out in our Supply Chains Delivery Plan (SCDP).[74] It is important, however, to highlight that existing plumbing and heating engineers have many of the core skills required to design, install, and maintain ZDEH systems such as heat pumps. For these skilled workers, upskilling can be supported through short courses (typically around 3-5 days) at a financial cost of £400 to £1,000.[75] Including the opportunity cost in the form of foregone revenue, the total economic cost of upskilling for one trader may be in the region of £1,200 to £2,500.[76]

73. In terms of the Standard Industrial Classification (SIC) of Economic Activities,[77] the subsectors likely to be most affected in manufacturing include 25.21, 28.21, and 28.25. In the construction sector, the subsectors most likely to be significantly affected include 43.21 and 43.22. Please see the notes accompanying Table 2 below to see what sectors these encompass.

74. Using data from the Business Register and Employment Survey (BRES) for Scotland, employment in the above sectors amounted to 52,540 in 2021, with the vast majority of this being concentrated in installation activities (97%) rather than manufacturing.[78] The median gross annual pay of jobs in these sectors ranges from a low of around £27,400 in sectors falling under SIC 25 to a high of around £37,400 in sectors falling under SIC 28.[79]

| SIC |

Year |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2015 |

2016 |

2017 |

2018 |

2019 |

2020 |

2021 |

|

| 25.21 |

160 |

110 |

140 |

160 |

150 |

170 |

220 |

| 28.21 |

80 |

40 |

70 |

50 |

60 |

170 |

150 |

| 28.25 |

1,640 |

1,480 |

1,715 |

1,415 |

1,395 |

1,595 |

1,295 |

| 43.21 |

19,950 |

16,770 |

18,000 |

14,620 |

16,200 |

17,435 |

26,925 |

| 43.22 |

15,435 |

16,760 |

17,790 |

16,895 |

18,625 |

14,725 |

23,950 |

| Total |

37,265 |

35,160 |

37,715 |

33,140 |

36,430 |

34,095 |

52,540 |

Notes: 25.21 corresponds to the sector "Manufacture of central heating radiators and boilers"; 28.21 corresponds to the sector "Manufacture of ovens, furnaces and furnace burners"; 28.25 corresponds to the sector "Manufacture of non-domestic cooling and ventilation equipment"; 43.21 corresponds to the sector "Electrical installation"; 42.22 corresponds to the sector "Plumbing, heat and air-conditioning installation"

75. Employment in these four sectors as a share of total employment is highest in West Lothian at 7% in 2021, with this being followed by North Lanarkshire at 6%, Midlothian at 3%, and Moray also at 3%. These are the only four local authorities for which the share is higher than the average share across all 32 local authorities (2%).

76. In terms of the Standard Occupational Classification (SOC), the latest Annual Survey of Hours and Earnings (ASHE) suggests the median gross annual pay of Scottish electricians and electrical fitters (SOC 5241) was between £30,900 and £37,800 in 2022, with the median gross annual pay of plumbers and HVAC installers (SOC 5315) sitting between £33,100 and £41,300.[81] These compare with a Scottish median gross annual pay across all SOCs and full- and part-time workers of just over £27,700.[82]

5.4 Third sector

77. It is envisaged that the impact on the third sector should not be any different from those other sectors identified above. There were no specific impacts identified within analysis of the consultation responses received. Three respondents made references to charities or third sector organisations in response to the scoping consultation. However, the points made were similar to those made for non-third sector organisations (e.g., the need to increase consumer awareness).

Contact

Email: 2024heatstandard@gov.scot

There is a problem

Thanks for your feedback