Overcoming barriers to the engagement of supply-side actors in Scotland's peatland natural capital markets - Annexes Volume

Research with landowners and managers in Scotland to better understand their motivations and preferences to help inform the design of policy and finance mechanisms for high-integrity peatland natural capital markets.

Appendix 2: Expanded methods and results

Sampling aims

The aspiration was to gather a sample representing a diverse range of owner types (e.g., individual private owner, corporate private owner, crofted estate owner, farmer, tenant farmer, crofter, community landowner, NGO landowner etc.) and ownership scales in each of the three regions. This was motivated by the aim of representing different regional socio-economic and environmental contexts. The sampling process was also intended to include estates with different objectives (e.g., conservation holdings including NGOs, mixed objectives and sporting / recreational estates), as well as forestry managers, community landowners / managers and larger and smaller-scale in-hand farmers and tenant farmers, in addition to crofters.

Ultimately, the sample aimed to be broadly representative of the diversity of Scottish landowners to ensure that our results are relevant and applicable to all types of natural capital supply side actors. The research team sought to include fringe stakeholders and those whose concerns might otherwise be drowned out by the ‘usual suspects.’ Finally, we sought a sample that would reflect the distribution of the volume of peat among these actors.

This project focused on understanding the barriers and motivations of land managers who have potential to host peatland restoration projects. With this in mind, the research team aimed to have 80% of participants from this group and therefore make them the focus of data collection. However, it was recognized that there are several other key actors who have broad perspectives and key insights on the peatland natural capital space, including:

- Land agents, advisors and brokers to the land management community

- Nature-based solutions project developers

- Financial advisors and brokers to natural capital investors and policymakers

- Other actors who span these groups

To capture these important perspectives, some of these demand-side and national-level actors were included in data collection and workshops were opened up to the wider networks the research team contacted to secure participants.

Additional details about interview themes

The interviews explored the following themes, building out of the Literature review (see Appendix 1):

- Individual, social and material factors creating barriers to engagement with Peatland Action, the Peatland Code and blended finance options being considered by SG, considering each of the four scenarios described above, with particular focus on blended finance options. Questions about the first two business as usual scenarios included how this group perceive current and potential future public support for peatland restoration and forest expansion (and trade-offs between these).

- An assessment of the motivations, social norms, decision criteria, and perceived risks and benefits that may influence the acceptability to supply-side actors of public, private and blended finance approaches to resourcing peatland restoration. The topic guide was informed by relevant theoretical frameworks based on the high-level review of behaviour change literature in the evidence review (see Appendix X).

- An assessment of proposed interventions to assess whether they would encourage participation, e.g. guarantees, tapering subsidies for restoration down to zero (like with renewables), subsidised training courses for restoration activities, IHT rule changes, better understanding of the Peatland Code and/or market dynamics.

Participant profile details

A suite of survey questions was used to evaluate respondents’ profile details and environmental views to help to characterise the sample. Many of these questions were ‘tick all that apply’, meaning that one individual could select more than one response. In these questions, counts are references using the shorthand f for frequency rather than n for number of people. Other survey questions were only presented under certain conditions, depending on a respondent’s prior answers. This was done to ensure the relevance of survey questions. It means that the sample base varies across different survey questions.

Connectedness to nature and environmental self-efficacy

An overwhelming majority of respondents on this question, 70% to be exact, strongly agree (n=16) with the statement, 'I feel personally connected to nature.' This suggests a deep bond or affinity with the natural environment among most respondents. In addition, 22% agree (n=5) with the sentiment. Finally, there is a smaller fraction of 9% who somewhat agree (n=2).

Interestingly, none of the respondents chose a neutral or disagreement stance. This unanimous sentiment underscores the universal appeal and importance of connection to nature for respondents.

In the assessment of environmental self-efficacy, a striking 87% strongly disagreed (n=20) with the statement, 'There is nothing I can do personally to help protect the environment.' This sentiment speaks to their resolve to be active agents of change. There is also a small group of 9% who disagreed (n=2), echoing the conviction that personal actions indeed matter when it comes to safeguarding the environment. In stark contrast, just one person (4%) strongly agreed (n=1) with the statement. Interestingly, there were no neutral or somewhat agreeing or disagreeing responses.

Climate change attitudes

A substantial 91% agreed (39% strongly agree; 43% agree; 9% somewhat agree) that it is a high personal priority (‘Climate change is a high priority for me personally’). At the same time, none of the respondents chose to disagree, indicating that none dismiss the importance of climate change. This unanimous agreement underscores the respondents' recognition of the threat that climate change poses and their commitment to address it. Interestingly, a modest 9% stayed neutral (n=2).

In response to the statement that 'Climate change is irrelevant to my role as a land owner/manager', an even more resounding 96% disagreed (83% strongly disagree; 13% disagree). A meagre 4% somewhat disagreed (n=1), contributing to the universal disagreement with the reverse-coded statement. No participant opted for neutral or agree at any level, further underlining the strong consensus among respondents.

Nature restoration views

On the issue of restoring peatlands (‘Restoring peatlands is a major personal priority for me’), a significant 57% of respondents agreed that it should be considered a high priority (22% strongly agree; 35% agree; 9% somewhat agree). 26% of participants remained neutral (n=6). However, the presence of a small percentage of disagreement cannot be overlooked (4% somewhat disagree and another 4% strongly disagree).

In the sphere of land management, a commanding 95% of respondents agreed that protecting the natural environment stands as their top priority (43% strongly agree; 35% agree; 17% somewhat agree). This emphatic consensus with the statement, 'In the context of land management, protecting the natural environment is my top priority,' speaks to a collective recognition of the paramount importance of environmental stewardship and conservation among respondents. Just one person disagreed (strongly disagreed) in any way, and there were no neutral responses to this question.

Despite this clear endorsement of nature restoration as the participants’ priority, a reverse-coded item revealed a wider range of perspectives. While 95% had agreed that environmental protection was their top priority, the statement ‘Financial return on investment is my top priority when it comes to managing land’, also garnered considerable support. With regard to prioritizing financial return on investment in land management, 52% agreed (9% strongly agree; 17% agree; 26% somewhat agree) that this financial aspect is paramount. Conversely, a substantial 39% disagreed (9% strongly disagree; 4% disagree; 26% somewhat disagree) with the statement, implying that for many, financial return is not the primary objective in managing land. Finally, a modest 9% remained neutral (n=2) on the issue, perhaps reflecting those whose decisions balance financial returns with other environmental, social, or personal considerations.

This range of perspectives highlights the complexity and diversity of land management priorities and approaches, given that there are a substantial number of respondents who said that both environmental protection and financial return were their top priority. This suggests that altruistic appeals to landowners and managers must make an effective case on the financial dimension as well to be successful.

Food, cultural heritage and public access

In the context of 'prioritising food production in management decisions', the perspectives among respondents diverge considerably. A total of 43% expressed agreement (strongly agree 4%; agree 17%; somewhat agree 22%) with the statement, suggesting that for many, food production forms a critical component of their land management strategies. However, another 34% of respondents conveyed disagreement (strongly disagree 4%; disagree 17%; somewhat disagree 13%), indicating that they assign greater weight to other facets of land management. 22% of those who responded to this question (n=5) remained neutral.

Turning to the emphasis placed on 'cultural heritage in management decisions', an overwhelming majority concurred with its importance. A significant 91% (strongly agree 14%; agree 45%; somewhat agree 32%) asserted the significance of cultural heritage in their management approaches. A marginal 9% (n=2) adopted a neutral stance, while none of the participants expressed any form of disagreement. This strong endorsement for the statement underscores the profound significance that participants place on preserving and honouring cultural heritage in their roles as land stewards.

As for the statement regarding 'providing public access for recreation' in management decisions, responses were varied. Nearly half of the participants, 48% (strongly agree 9%; agree 17%; somewhat agree 22%), acknowledged that accommodating public access for recreational purposes is a key priority in their decision-making. In contrast, 35% (strongly disagree 9%; disagree 4%; somewhat disagree 22%) did not affirm the view that ‘I prioritise food production in my management decisions’. A further 17% (n=4) remained neutral.

Decision-making authority for peatlands land management

Respondents indicating ownership of peatlands were assumed to have decision-making power for land management, enabling them to provide authentic assessments of the policy scenarios tested in this research. To check the decision-making power of those in other respondent categories, the survey asked about their authority to make decisions about the use of land containing peatlands. Out of the total responses to this question, 33% (f=9) reported that they do not hold the decision-making authority over how such land will be used. However, a more substantial portion of respondents, 67% (f=18), affirmed that they do possess the power to make decisions regarding the use of peatlands. Among those who said they did not hold such authority, all of them answered yes to the question: ‘Are you able to advise or otherwise influence decisions by peatland landowners’.

This indicates that most respondents in this survey sample have a direct hand in decision-making processes related to the use of peatlands, either through direct ownership or delegated authority, and those who did not were nevertheless in a position to influence such decision-making. This latter category of respondent was asked a truncated set of questions, skipping items about land under their management, for example.

Details of land owned / managed by respondents

Those with direct decision-making power for peatlands management were asked questions about the land they own or manage.

Landholding size compared to area with peat

Respondents were given the option of describing the land size in hectares or acres. The survey also collected data on the size of landholdings, measured in hectares (ha). The landholding sizes reported in hectares varied widely, ranging from as little as 6 ha to as much as 80,000 ha (Mean: 7374 ha). For those reporting in acres, the range was similarly expansive, from 300 ac to 96,000 ac (Mean: 20,645).

The amount of this land with peat that respondents reported was considerably smaller, ranging in hectares from 0 (n=1) to 6,000 ha (n=1) (Mean: 1240 ha).

Primary uses for overall landholding

The respondents were asked to detail their main management or business activities in the survey[1]. A strong majority, 72% of responses (f=28), indicated Low intensity (sheep) farming as one of their main activities. This was followed by Peatland restoration/land stewardship, which accounted for 62% of responses (f=24). Forestry and Tourism/recreation were each reported by 46% of responses (f=18 for each), highlighting their importance as well. Low intensity (beef) farming was the main activity for 44% of responses (f=17), and Sporting activities/rearing of game was indicated by 38% of responses (f=15). None of the respondents reported Peat extraction as their main activity.

Some respondents chose 'other' and specified their main management or business activities in more detail. Their responses reflect a wide range of activities related to wildlife, conservation, energy generation, agriculture, and property management. A few respondents mentioned activities focused on environmental conservation and restoration, such as "wildlife reserve", "ecological restoration", "habitat conservation", and a "rewilding project" with the aim to re-establish more woodland cover and maintain a balanced population of herbivores (and potentially carnivores). Hydroelectric power generation was also mentioned by two respondents, with one also indicating an involvement in "golf". "Agricultural activities" were indicated by two respondents, with one involved in "deer farming" and "brewery", and another practicing "occasional and limited cattle grazing for up to 20 cows". Finally, one respondent listed "property" as their main activity. While this response is less specific, it might refer to property management, property development, or similar activities.

Sporting interests on the peatlands area

Respondents were asked whether there were any active sporting interests on the peatlands they own or manage. A slight majority, 57% (f=21), confirmed the presence of such interests. However, a significant portion, 43% (f=16), stated that there were no active sporting interests on their peatlands. This indicates a fairly even distribution of respondents in terms of active sporting usage on their peatland properties.

The respondents who reported active sporting interests on the peatlands they own/manage were asked about the specific categories of sporting interests. A majority of the respondents with sporting interests, 81% (f=17), reported Deer stalking as an active sporting interest on their land[2]. Following this, Rough Shooting was the next most frequently indicated category at 43% (f=9). Slightly fewer respondents reported Grouse shooting at 38% (f=8), and Driven shooting was reported by 29% (f=6) of the respondents. Lastly, only a single response mentioned Wildfowling as a sporting interest currently active on their land.

Peatlands grazed by livestock and deer

When asked whether their peatlands were grazed by livestock, a considerable majority of respondents, 71% (f=27), affirmed this practice. However, a smaller but significant portion, 29% (f=11), reported that their peatlands were not subjected to grazing by livestock. This indicates that grazing is a common activity on peatlands owned or managed by the respondents.

The respondents provided a variety of livestock types and stocking densities for their peatlands. Sheep were the most commonly mentioned livestock, with several breeds such as Blackface, Hebridean, and Cheviot being named. Stocking densities for sheep varied significantly, ranging from around 1 ewe per 2 hectares to 1 ewe per 3 hectares, and even up to 3 ewes per acre. One respondent noted a count of 1,200 ewes across approximately 2,500 hectares, and another mentioned 1,100 on one part of their land and 680 on another.

In addition to sheep, cattle were also commonly mentioned. They were sometimes reported to graze alongside sheep, and at other times as the primary livestock. Cattle densities were described as "very low" or "at a stocking rate of roughly 1 cow per 20 hectares." One respondent provided a specific headcount of 55 cattle alongside 700 ewes.

Several respondents noted the importance of rotational livestock grazing, highlighting that stocking densities varied throughout the year and that it was not a constant factor. Some respondents indicated their stocking density by using the term "Livestock Unit" or "LU" per hectare, such as "0.1 LU/Ha" and "0.25LU/ha". Finally, a few respondents indicated that they didn't have exact numbers, as the livestock were managed by a grazings committee or the stocking density varied across different areas of the peatland. One response indicated that their peatland area was not grazed at all.

In addition to livestock grazing, most respondents, 84% (f=31), indicated that their peatlands are grazed by deer on this ‘tick all that apply’ survey question. Just 16% (f=6), reported that their peatlands are not grazed by deer. Responses to deer grazing densities on peatlands varied widely among the respondents, with several respondents unsure of the exact numbers. Some respondents specified densities, ranging from “1 deer per square km” to “between 9 and 6 deer per square kilometre” and “10-12 deer per sq.km”. A few respondents noted that the deer were not resident and moved between their lands and other areas. Some reported seeing only occasional deer or a small number of deer, while others reported higher densities, with one respondent aiming for “5-7 deer / ha” but had “15-20 at helicopter count this year”. There were also those who reported not knowing the densities or that their responses were to be confirmed. It should be noted that the type of deer was specified by some respondents, with the majority mentioning Roe deer and a few also mentioning Red deer.

Wind turbines and other activities on peatlands area

Among the respondents, a very small minority, only 5% (f=2), reported having installed wind turbines in their peatlands (one reported a single turbine and the other had 50 turbines).

Respondents mentioned a variety of other activities taking place on their peatlands. Some activities are related to recreation, such as walking (mentioned in the context of "right to roam"), fishing, public access and camping, hill walking, and occasional mountain biking. Other respondents spoke about environmental and conservation activities, such as biodiversity conservation, removal of birch scrub, Sitka and Rhododendron, moth trapping and dragonfly survey/recording by local enthusiasts, and peatland scorecard testing for NatureScot POBAS project.

One respondent specified their peatland was only used for livestock grazing. Another respondent shared a detailed account of their activities which included planting trees with the guidance of the Woodland Trust, supporting biodiversity (specifically wader birds), and occasional browsing of Soay sheep on the fenced peat area. This respondent also noted a previous planning permission for a house to be built on the peatlands, which they chose not to follow through with, instead opting to restore the peatland area. Five respondents indicated there were no other activities taking place on their peatlands.

Peatland status

Respondents were asked about the conditions of the peatlands they own or manage[3]. The highest proportion of responses indicated that their peatlands were in two categories: Areas in good condition with no bare peat or drainage (76%, f=29), and Areas where there are small patches of bare peat (74%, f=28). The next most common condition was Areas of land that contain drains, which was identified by 66% of responses (f=25). Slightly less than half of the responses, 45% (f=17), indicated Areas where there is extensive bare peat that is actively eroding (with haggs and gullies).

A minority of respondents, 13% (f=5), were Not sure about the condition of their peatlands. In these cases, they were asked to, ‘Please describe the condition of your peatlands in your own words’.

The respondents who indicated they were 'Not sure' about the condition of their peatlands in response to the pre-established categories were asked to describe it in their own words. Their responses reflect a range of conditions and contexts. One respondent observed evidence of historical peat cutting on their land, dating back to the pre-1900s and perhaps even earlier, as the land was cleared in the early 1800s. More recent peat cutting, they speculated, likely occurred from the 1920s onward but mainly in the common grazing area. Another respondent had undertaken extensive peatland restoration on around 1,000 hectares of their land and noted the obvious beneficial effects. They pointed out the ecological role of deer on their land, approximately 11 deer per square kilometre. They argued that deer contribute to the creation of bare spots that become habitats for pioneer plant species, thus contributing to biodiversity. One respondent noticed their wet ground was slowly being taken over by self-seeded Sitka spruce, an observation which indicates some ecological changes in their peatlands. A respondent mentioned having completed surveys and restoration work on their peatland but did not specify the results or the specifics of the work undertaken. Lastly, a respondent expressed continued uncertainty about the condition of their peatlands, saying it might be ‘mixed’.

Peatland restoration views and experiences

Respondents were asked if any part of the peatland they own or manage was in need of restoration. The majority, 83% (n=24), answered yes, indicating that they saw a need for restoration in their peatlands. On the other hand, a smaller group of respondents, 17% (n=5), believed that their peatlands did not require any restoration. Additionally, 8 respondents were unsure about the need for restoration in their peatlands.

When asked about their experience with peatland restoration, the majority of respondents, 65% (f=24), stated that they had experience with such projects. At the same time, 35% (f=13), indicated they did not have any experience with peatland restoration.

Peatland ACTION

Peatland ACTION is a project that provides funding to improve the condition of degraded peatlands across Scotland. It is a partnership between NatureScot, Forestry and Land Scotland, Scottish Water, Loch Lomond and the Trossachs National Park Authority, and Cairngorms National Park Authority. Here, we investigate existing awareness of this project and reported experiences.

Awareness

When asked about their awareness of Peatland ACTION prior to their participation in this research, a significant majority of respondents, 88% (n=44), stated that they had heard of Peatland ACTION before. On the other hand, a small minority of participants, 12% (n=6), indicated that they had not been aware of Peatland ACTION prior to their involvement in this research.

Among the respondents who had heard of Peatland ACTION, the majority indicated a high level of familiarity with the organisation. More than half of these participants, 52% (n=23), described themselves as being Extremely Familiar. Further, 27% (n=12) stated that they were Moderately Familiar with Peatland ACTION. A smaller proportion, 14% (n=6), reported being Somewhat Familiar, while a minority, 7% (n=3), described their familiarity as Slightly Familiar. Importantly, none of the respondents reported not being familiar at all with Peatland ACTION.

Direct experiences

A large majority of respondents, 86% (n=36), reported having had direct experience or communications with Peatland ACTION. However, there were still a small percentage, 14% (n=6), who had not had any direct experience or communication with the organisation.

For respondents who had direct experience with Peatland ACTION, we sought to understand the nature of their interactions. A majority, 77% (f=27), reported that they had received advice on the management or restoration of their peatlands, signifying the organization's crucial role in providing guidance on peatland care. Additionally, 74% (f=26) had received funding for a Peatland ACTION project(s), emphasising the financial support Peatland ACTION provides for peatland restoration and conservation efforts.

Interestingly, a significant proportion, 46% (f=16), specified having 'Other experience or interactions with Peatland ACTION.' The "other experiences" with Peatland ACTION mentioned by the respondents were diverse, showcasing a range of interactions with the organisation. For some, it meant being in the process of "certifying projects with the Peatland Code," while for others, it was about participating in a "Funding mentor scheme."

Some respondents had a direct employment connection to the organisation, that is, they worked for Peatland ACTION. For some, their engagement with Peatland ACTION extended to advocacy and policy discussions, such as having "Discussions about how we ensure public money for peatland restoration benefits the local communities." Meanwhile, others appreciated the training and guidance provided by the organisation, noting that "Peatland ACTION provide very helpful training and guidance to support us in our work designing high-quality restoration plans."

The collaborative nature of Peatland ACTION's work was evident, with one respondent highlighting their "continuous dialogue on project progress, new developer support scheme and training opportunities, amongst others." Another pointed out their association with the organization through the Galloway and Southern Ayrshire UNESCO Biosphere, stating, "I have seen Peatland restoration in action through Scottish Land and Estates and a visit to a neighbouring estate."

Finally, some were engaged in more hands-on roles with Peatland ACTION. One respondent mentioned that they had a project that "had to be reviewed with a revised plan introduced that required discussion with Peatland ACTION." Another was awaiting Nature Scot's decision on a project, stating, "Proposed Peatland ACTION project on […] Common Grazing land, all survey work etc. completed, currently awaiting Nature Scot's decision in regard to a direct funding option for the project."

The respondents who reported not having any direct experience with Peatland ACTION had a few different reasons for this. One respondent shared that all their interactions were "dealt with by an agent," hence they did not have any direct experiences. Another respondent felt that Peatland ACTION mainly targets "much larger projects and not farms like our small family farm." For one respondent, a developer served as an intermediary with Peatland ACTION, which resulted in them not having any direct experiences. Lastly, a respondent mentioned that it was "difficult to see how to approach them," indicating a possible barrier in terms of accessibility or clarity in how to engage with the organisation.

Peatland Code

The Peatland Code serves as a voluntary certification standard for peatland projects across the UK that aim to commercialise the climatic advantages of peatland restoration. It confirms for buyers in the voluntary carbon market that the climate credits they are purchasing are genuine, measurable, additional and permanent.

A significant majority of respondents, 92% (n=44), reported that they had heard of The Peatland Code before participating in this research. However, a small portion of respondents, 8% (n=4), had not previously heard of The Peatland Code.

Out of the respondents who had heard of The Peatland Code, 29% (n=13) indicated they were extremely familiar with it, 24% (n=11) were moderately familiar, 29% (n=13) were somewhat familiar, and 18% (n=8) were slightly familiar. No respondents reported being completely unfamiliar with The Peatland Code. The mean level of familiarity was moderately familiar with a score of 3.64 out of 5, while the mode, or most frequently selected option, was extremely familiar.

Of those who had heard of The Peatland Code, 41% (n=16) reported having no direct experience or communications with The Peatland Code, while a majority of 59% (n=23) confirmed they had such interactions. For those who reported having direct experience with The Peatland Code, a variety of experiences were indicated. The largest group, comprising 74% (n=17) of respondents, said they had started or completed the capital works for a Peatland Code project on their land. Additionally, 70% (n=16) had applied for a Peatland Code project, either in the past or currently in progress. Further, 57% (n=13) had received advice on the potential for a Peatland Code project on their land. Lastly, 48% (n=11) cited other experiences or interactions with the Peatland Code.

The responses from those who reported 'other experiences or interactions' with The Peatland Code included a variety of activities. Some respondents noted project involvement, such as one who had "1 x validated PC project, 1 x project going through validation, 1 x due to be registered," and another who acted as an agent on behalf of landholders wishing to put their projects through the Peatland Code. Another respondent had been part of the original Defra-funded project to develop the Peatland Code at the Crichton Carbon Centre.

One respondent indicated that their organisation had investigated the applicability of the Peatland Code to their purpose and objectives for peatland restoration. Some respondents reported engagement through funding applications, site visits, and promotional videos, while others have had direct interactions with administrators at conferences. In-depth discussions about the Peatland Code, such as reviewing protocols, definitions, and outcomes, were also mentioned. One respondent, who had worked with the Code in a professional capacity, noted that the Peatland Code team had assisted in clarifying elements of the Code when necessary. They had also been involved in workshops updating the Code as part of the consultation process with project developers. Lastly, some landholders had enquired about eligibility for the Code.

The respondents who reported no direct experiences with The Peatland Code provided various reasons for this. Some mentioned that they were unaware or unsure about it; one respondent stated, “I don't recall this ever being mentioned by my SNH/NatureScot Peatland ACTION officer”, while another reported being “unsure where to get it”.

Several respondents indicated they were using intermediaries or advisors to deal with The Peatland Code. For instance, one respondent said, “I am using a developer as an intermediary”, while others mentioned they "dealt with a broker who has knowledge of the Peatland Code" and “have used advisors who have worked directly with Peatland Code”. Others indicated that they have not yet felt the need to engage with The Peatland Code. One respondent said they "haven't needed to yet," and another planned to "explore in detail when time allows and it is relevant to do so."

Finally, one respondent explained that their current policy is to "retain all ecosystem credits, including carbon credits, until we understand better the requirements for demonstrating the sustainability qualities of our own business." This implies that they are taking a cautious approach to engaging with carbon offset schemes such as The Peatland Code.

Other advisory services and programmes for peatland restoration

Finally, we asked ‘Have you encountered other advisory services, programmes or other sources of information about peatland restoration?’. The survey results show that a majority of respondents (69%, n=31) have encountered other advisory services, programmes or other sources of information about peatland restoration. In contrast, 31% (n=14) reported not being aware of any such sources or services.

Participants in the survey mentioned that they have accessed various other advisory services, programmes, or information sources about peatland restoration. These include the IUCN Peatland Programme and numerous webinars. Some have gained insights from the Farming Advice Service (FAS), DEFRA, SNFP, and NFUS. The Loch Lomond and Trossachs National Park also emerged as a source of information.

Certain respondents drew upon past experiences working on peatland restoration projects and engagements with leading consultants like Strath Caulaidh. The Carbon Crichton Centre was another source of knowledge for some. The Tweed Forum and Crichton Carbon Centre also were mentioned as important sources of information and support.

Several respondents have encountered SRDP - AECS, EU Life projects, NatureScot funded projects, and Forestry and Land Scotland funded projects. Others reported acquiring knowledge from research and news media. Advice from the SAC, NFUS, and Crofting Federation, along with senior level guidance from the Crofting Commission, has helped a few respondents in their peatland restoration activities.

The FAS and Coalfield Environment Initiative also provided information to some respondents, as did the Yorkshire Peat Partnership and IUCN Conferences. A few have been approached by private companies offering to assist with peatland restoration for a fee.

In terms of training and advice, the Scottish Crofting Association's info/training day with RSPB and the Working for Waders information site were valuable resources. Additionally, some respondents benefitted from Scottish Government leaflets and website information.

NatureScot, Forest and Land Scotland, Galbraith, and land agents were mentioned as additional sources of advice and information. Moreover, respondents have utilized knowledge from global initiatives such as the Global Peatland Initiative and the Great North Bog Initiative. Finally, others mentioned the insights gained from organizations such as Angus Davidson and the Yorkshire Peat Partnership.

Research instruments

Pre-interview survey questions

Guidance for research users / funders

About this structured interview

There are two sections to this interview. The first is a self-completion online survey to be completed prior to the interview. The second is a live interview to go through open-ended questions. This structure is required to keep the live interviews to not more than an average of one hour each.

Procedure

Step 1 – Invite participant to do the self-completion element of the survey prior to the scheduled interview (indicate preferred and hard deadline). {If not completed by the deadline, either the interview will need to be rescheduled or additional time will need to be added to the interview to go through the full set of questions through verbal administration}

Step 2 - The live interview will address (a) any gaps in responses to the Step 1 advance online survey and (b) will gather responses to open-ended questions, probing the reasons for their initial responses to the different finance mechanisms.

Profile

- First name

- Last name

Which of the following apply to your connection with peatlands in the study area? (tick all sub-categories that apply)

- Owner

- Landlord – Crofting estate

- Private estate

- Community estate

- Farm owner

- Farm owner – Contract farming agreement

- Tenant

- Grazing Let

- Limited Duration Tenancy (LDT)

- Modern Limited Duration Tenancy (MLDT)

- Short Limited Duration Tenancy (SLDT)

- Secure Tenancy

- Limited Partnership

- Crofter

- Crofting tenant

- Crofting owner occupier

- Common grazings user

- Common Grazing Committee

- Sheep Stock Club

- Common Grazing Shareholder

- Land agent, advisor, broker, project developer

- Factor or estate manager

- Other (please specify)

[If anything other than Owner is selected] Do you have the authority to make decisions about how land containing peatlands will be used? (Y/N/Unsure)

[If ‘Yes’, then the interview continues in full]

[If ‘No’ or ‘Unsure’ is selected] Are you able to advise or otherwise influence decisions by peatland landowners? (Y/N/Unsure)

{Helper text: e.g., select ‘Yes’ if you are a tenant or crofter who informs or collaborates in decision-making with your landlord, or are you a land agent, advisor, broker, project developer?}

[If ‘yes’, skip to section: ‘Programme Awareness and Experiences’]

[If ‘No’ or ‘Unsure’ is selected for both of the above questions, then the participant has been incorrectly identified for this study. The interview would then go directly to the ‘thank you’ and finish step.]

What is the land holding name(s) or reference(s) for the peatlands you own/manage? [open response]

Would you prefer to report the size of your landholding in hectares or acres?

- Hectares

- Acres

[If Hectares selected] What is the approximate size of your landholding? [Integer] ____ Hectares

[If Acres selected] What is the approximate size of your landholding? [Integer] ____ Acres

What is the approximate area of peat within your landholding?

[If Hectares selected previously] [Integer] ____ Hectares

[If Acres selected previously] [Integer] ____ Acres

What are the main management or business activities in the landholding?

- Sporting activities/rearing of game

- Peatland restoration/land stewardship

- Low intensity (sheep) farming

- Low intensity (beef) farming

- Forestry

- Tourism/recreation

- Peat extraction

- Other (please specify)

Are any of the peatlands you own/manage in the following condition? (tick all that apply, and only if possible, indicate the approximate area or proportion of your peatlands in each category)

- Areas where there is extensive bare peat that is actively eroding (with haggs and gullies)

- Areas where there are small patches of bare peat

- Areas of land that contain drains

- Areas in good condition with no bare peat or drainage

- Not sure (please describe the condition of your peatlands in your own words)

[If ‘areas where there is extensive bare peat’ selected] Area or approximate proportion of peatland that is actively eroding (bare or with haggs and gullies)? (in hectares or %)

Hectares ___ Percentage ____

[If ‘Areas where there are small patches of bare peat is selected] Area or approximate proportion of peatland where there are small patches of bare peat? (in hectares or %)

Hectares ___ Percentage ____

[If ‘drained’ selected] Area or approximate proportion of peatland that has been drained (either artificially or via a network of gullies)? (in hectares or %)

Hectares ___ Percentage ____

[If the response selected is ONLY the condition is ‘near natural’] Is any part of the land you own/manage that contains peatlands needing restoration? (Y/N/Unsure)

[If overall = near natural condition / no need for restoration and answer is ‘no’ or ‘unsure’ to ‘is any part of the land you own or manage that contains peatlands needing restoration?’] ‘Please answer the rest of the questions in this survey as if the land you own/manage needs to be restored. (The focus of this research is to understand the views of landowners or managers about different finance mechanisms for peatlands restoration)’

[If overall = good condition and answer is ‘yes’ to ‘Is any part of the land you own/manage that contains peatlands needing restoration?’] Please answer the rest of the questions in this survey focusing only on the peatlands you own/manage that need restoration.

Are there any active sporting interests on the peatlands you own/manage? (Y/N)

[If yes] Please select all the sporting interests that are currently active on the land. (tick all that apply)

- Grouse shooting

- Driven shooting

- Rough Shooting

- Deer stalking

- Other (please specify)

Are your peatlands grazed by livestock? (Y/N)

[If yes] Provide species and stocking density [open question]

Are your peatlands grazed by deer? (Y/N)

[If yes] What are the approximate densities? [open question]

Have you installed wind turbines in your peatlands? (Y/N)

[If yes] How many, and over what area? [open question]

What other activities take place on your peatlands? [open question]

Programme Awareness and Experiences

Overall, how well informed do you feel about peatland restoration? (on a scale of 0 being not at all well informed and 100 being extremely well informed)

Peatland Action

Have you ever heard of Peatland Action [embed website link] before taking part in this research? (Y/N/Unsure)

[If yes] How familiar are you with Peatland Action?

Not at all – Extremely scale

[If yes to ‘have heard of’ and familiar at a level greater than ‘not at all’] Have you had any direct experience or communications with Peatland Action? (Y/N/Unsure)

[If yes] Have you received any of the following (tick all that apply):

- Funding for a Peatland Action project(s)

- Advice on the management or restoration of your peatlands

- Other experience or interactions with Peatland Action (please describe) [open response field revealed]

[If no] Is there any particular reason you have not had direct experience with Peatland Action?

The Peatland Code

Have you ever heard of The Peatland Code [embed website link] before taking part in this research? (Y/N/Unsure)

[If yes] How familiar are you with The Peatland Code?

Not at all – Extremely scale

[If yes to ‘have heard of’ and familiar at a level greater than ‘not at all’] Have you had any direct experience or communications with The Peatland Code? (Y/N/Unsure)

[If yes] Have you experienced the following? (tick all that apply)

- Applied for a Peatland Code project (in the past or in progress)

- Started or completed the capital works for a Peatland Code project on your land

- Received advice on the potential for a Peatland Code project on your land

- Other experience or interactions with the Peatland Code (please describe) [open response field revealed]

[If no] Is there any reason you have not had any direct experience with The Peatland Code? [open response]

Have you encountered other advisory services, programmes or other sources of information about peatland restoration? (Y/N/Unsure)

[If yes] Please list [open responses]

Consultation on Peatland Action and blended finance mechanisms

[Section guidance] This section of the survey aims to get your initial feedback on a range of scenarios that have been discussed as possible ways to boost investment in peatlands restoration. For each one, you will be asked to read a brief description, and then offer your feedback. You will have the opportunity to provide more extensive feedback in the follow-up interview linked to this survey.

Scenario A: Peatland ACTION only (Current):

- Capital costs: 100% capital grant from Peatland ACTION covers the capital works costs of restoration only (typically around £1500 per hectare).

- Maintenance costs: Long-term maintenance costs are covered by own funds (estimated at around £15-20 per ha per year).

- Profit: No other costs and no profit, leading to a net loss in the absence of revenue flows to cover long-term maintenance costs.

Scenario B: Peatland ACTION and Peatland Code (Current):

- Capital costs: Peatland ACTION covers the capital works costs of restoration (typically around £1500 per hectare), with revenues from sale of carbon credits covering maintenance and costs of running projects via the Peatland Code. To be eligible for this scheme, carbon funding must cover at least 15% of the project’s lifetime costs.

- Maintenance costs: Long-term maintenance is the responsibility of project owner but will be covered by the sale of carbon units.

- Profit: Any carbon revenues not needed to repay private investors and/or cover Peatland Code costs (for registration, validation and verification) and maintenance costs would be profit.

- Carbon revenue estimated to be around £40-70 per hectare per year on average at current prices but could significantly rise or fall.

- Project validation ranges from £1,500-2,500, depending on the size of the project.

- Registering with the Land Carbon Registry is a one-time payment of £400.

- Peatland Code projects are verified at year 5 and then at least every 10 years. Each verification costs about £2,000.

- Long-term maintenance costs of restored peatland are estimated to be ~£15-20 per ha per year.

Please note that the third and fourth peatland restoration finance scenarios described below are plausible but hypothetical, in that they do not describe current Scottish Government policy. The results of this research will play a role informing policy development on peatlands and private investment in natural capital.

Scenario C: Peatland ACTION (capped) and Peatland Code with public support for maintenance costs (Potential):

- Capital costs: Grant from Peatland ACTION capped at 50% of capital costs (reducing a typical grant by around £750 per hectare). The upfront finance need created by the lower Peatland ACTION capital grant can be met by the forward sale of carbon units or by accessing a private finance facility (potentially supported or managed by Scottish Government).

- Maintenance costs: Maintenance costs to be fully met for the first 10 years by grant funding.

- Profit: Any carbon revenues not needed to repay private finance, cover Peatland Code costs (for registration, validation and verification) and any additional maintenance costs after the first 10 years of the project would be profit.

- Carbon revenue estimated to be around £40-70 per hectare per year on average at current prices but could significantly rise or fall.

- Project validation ranges from £1,500-2,500, depending on the size of the project.

- Registering with the Land Carbon Registry is a one-time payment of £400.

- Peatland Code projects are verified at year 5 and then at least every 10 years. Each verification costs about £2,000.

- Long-term maintenance costs of restored peatland are estimated to be ~£15-20 per ha per year.

Scenario D: Peatland Code with guaranteed carbon price and public support for maintenance costs (Potential):

- Capital costs: 100% of capital costs met by a private finance facility (potentially supported or managed by Scottish Government).

- Maintenance costs: Maintenance costs to be fully met for the first 10 years by grant funding in the region of £15-20 per hectare per year at current prices.

- Profit: Scottish Government guarantees a minimum price paid for peatland carbon to cover project costs and ensure the project’s economic viability. If carbon prices are above the minimum carbon price guarantee, the project can benefit from the upside by selling its carbon credits directly in the market.

- Carbon revenue estimated to be around £40-70 per hectare per year on average at current prices but could significantly rise or fall.

- Project validation ranges from £1,500-2,500, depending on the size of the project.

- Registering with the Land Carbon Registry is a one-time payment of £400.

- Peatland Code projects are verified at year 5 and then at least every 10 years. Each verification costs about £2,000.

- Long-term maintenance costs of restored peatland are estimated to be ~£15-20 per ha per year.

Overall, how clear is this scenario to you, based on the description I just read? (on a scale of 0 being not at all clear and 100 being extremely clear)

Overall, how attractive is this scenario to you? (on a scale of 0 being not at all attractive and 100 being extremely attractive)

Please explain why you find this scenario [attractive/unattractive]? [open response]

Is there anything that could be done to make this scenario more attractive? [open response]

Keeping in mind the scenario described above, please indicate your level of agreement with the following statements: [strongly disagree to strongly agree – Likert-type scale block. Note: A ‘please explain’ box should show under each statement for any answer except ‘neutral’ or ‘no opinion’]

‘This scenario aligns with my personal values’

‘This scenario is a poor fit with my personal financial needs’ {reverse coded}

‘This scenario is too risky for me’ {reverse coded}

‘I would be keen to sign up to this kind of scenario’

‘In general, I think this scenario would be appealing to land owners/managers in Scotland’

‘Most land owners/managers in Scotland would find this scenario too risky’ {reverse coded}

[Questions above to be repeated until all four finance mechanisms covered]

Additional questions on Peatland Action and blended finance mechanisms

[Tenants and crofters only] If your landlord told you they were planning to restore the peatlands you manage with the goal of generating revenue from the sale of carbon via any of the mechanisms described above:

- Would you be prepared to support this work, if you are paid for any additional work required of you?

- If you would require some level of revenue sharing (from the sale of carbon credits) before you would willingly support this work, what would you expect as a minimum? {Helper text: You may answer either as a percentage of carbon revenues or on a £ per hectare/acre per year basis, assuming for the purposes of this question that Peatland Code revenues are £41 per hectare per year for at least 30 years. We assume that any agreement would be on a rolling basis for the duration of your tenancy, passing to future tenants if you were to give up your tenancy or it was not renewed.}

- What level of revenue sharing do you feel would be fair? {Helper text: Answer as a percentage of carbon revenues or £ per hectare/acre per year.}

[land agent, advisor, broker, project developer only] Would you advise landowners to enter benefit sharing agreements with tenants/crofters? (Y/N/Unsure)

[If ‘Yes’ is selected] What level of revenue sharing would you recommend to landowners? [open response] {Helper text: You may answer either as a percentage of carbon revenues or on a £ per hectare per year basis, assuming for the purposes of this question that Peatland Code revenues are £41 per hectare per year for at least 30 years.}

[If No selected] Why not? [Open response]

[If Unsure selected] Why are you unsure? [Open response]

[If the participant has experience with the Peatland Code] If you have a Peatland Code project (currently or in future), do you have a preference for forward-selling your carbon to cover project costs (avoiding the need for financing mechanisms), or selling carbon units as they are verified over the course of your project? (Please select the best option below) [radio button]

- Receive one upfront payment for the sale of all carbon credits that will arise from the project, noting that you will be responsible for maintaining the project for its full duration with these funds and / or via other sources of private capital.

- Sell carbon units as they are verified over the course of your project, recognising that carbon prices are likely to be higher, but could be lower than the rate you could get by forward-selling. This might require upfront borrowing from an investor or lender to cover early project costs until significant revenues from the sale of carbon can be generated.

- Receive a proportion of carbon revenue upfront, followed by regular payments for the remaining unsold units as they are verified over time. {Helper text: Restoration costs are on average £1500 per hectare.}

[If this option is selected] Can you provide an indicative estimate on the proportion of the overall payment or proportion of capital work costs you would look to secure upfront?

What % of upfront capital works costs would you want to cover by forward selling carbon units?

- Unsure

- Other (please explain) [open response if selected]

Your personal views

[Landowners and managers only – not advisors]

‘At this point, I would like to ask you about your personal views.’

Please indicate your level of agreement with the following statements (on a scale from Strongly disagree to Strongly agree) [statement order to be randomised]

'I feel personally connected to nature'

'There is nothing I can do personally to help protect the environment'

'Restoring peatlands is a major personal priority for me'

‘In the context of land management, protecting the natural environment is my top priority’

‘Financial return on investment is my top priority when it comes to managing land’

‘Climate change is a high priority for me personally’

‘Climate change is irrelevant to my role as a land owner/manager’

‘I prioritise food production in my management decisions’

‘’I prioritise cultural heritage in my management decisions’

‘Providing public access for recreation is a key driver of my management decisions’

Closing

Is there anything else you would like to add at this time about any of the topics in this survey? [open question]

Thank you for the time you have taken to complete this survey. We look forward to talking to you soon to explore some of your answers in greater depth. If you have any questions about this or need to re-arrange the time of your interview, please contact Brady Stevens: Brady.Stevens@sac.co.uk

Interview questionnaire

Live interview section

Guidance for interviewers

Interviews to follow a standardised structure to ensure comparable data are obtained. Please ensure that informed consent materials are provided to the participant in advance of the interview [including any information about participant compensation]. Verbal confirmation of consent to participate should be recorded at the outset of the interview.

Consent

Guidance for interviewers

Go through the steps below to confirm consent, using the exact language in quotations wherever feasible to maintain consistency.

1) ‘I am now going to turn on my recorder to ensure that your responses are fully captured for our analysis’.

2) START RECORDING

3) ‘As a reminder, your responses will be kept confidential by default. Do you have any questions about this research before we get started?’

4) [after addressing any questions or participants indicating that they don’t have questions] ‘Can you please confirm your consent to participate in this research?’

5) Participant confirms consent

Motivations to restore peatland

[Question logic from pre-interview survey: If the survey indicates the participant has not restored peatland previously] Why have you not restored peatlands? [Follow-up if needed: What are the main barriers?]

[Question logic from pre-interview survey: If the survey indicates the participant has restored peatland previously, are considering restoration or have advised clients to restore]

In your experience, what were the main barriers you had to overcome to proceed with peatland restoration? {Helper text: prompts may include restoration not being compatible with objectives, not being financially viable, being restrictive for future land use change, not being farming or productive, and peers not doing it/culture.}

[open response]

What are your main reasons for restoring peatlands, in your experience? {Helper text: prompts may include income generation, environmental improvements, compatibility with existing land uses, advice and guidance, changing policy direction, peer influence)

[open response]

Consultation on Peatland Action and blended finance mechanisms

[Section guidance] This section of the interview aims to get your initial feedback on a range of scenarios that have been discussed as possible ways to boost investment in peatlands restoration. You already read and answered questions on these in the pre-interview survey, but I will re-read the description of each one to refresh your memory, before asking questions about it.

Scenario A: Peatland ACTION only (Current):

- Capital costs: 100% capital grant from Peatland ACTION covers the capital works costs of restoration only (typically around £1500 per hectare).

- Maintenance costs: Long-term maintenance costs are covered by own funds (estimated at around £15-20 per ha per year).

- No carbon revenue: No revenue from sale of carbon units.

- Profit: Net loss due to the absence of revenue flows to cover long-term maintenance costs.

- Risk: Liability for long term maintenance costs (unknown at outset).

Scenario B: Peatland ACTION and Peatland Code (Current):

- Capital costs: 100% capital grant from Peatland ACTION covers the capital works costs of restoration only (typically around £1500 per hectare).

- Maintenance costs: Long-term maintenance costs are covered by own funds (estimated at around £15-20 per ha per year).

- Carbon revenue: Revenue from sale of carbon units awarded through the Peatland Code.

- Profit: Potential for upside. Any carbon revenues not needed to cover maintenance costs and Peatland Code costs would be profit.

- Risk: Liability for long term maintenance costs (unknown at outset) and peatland code compliance costs must be covered by sale of carbon units.

- Please note that the third and fourth peatland restoration finance scenarios described below are plausible but hypothetical, in that they do not describe current Scottish Government policy. The results of this research will play a role informing policy development on peatlands and private investment in natural capital.

Scenario C: Peatland ACTION (capped) and Peatland Code with public support for maintenance costs (Potential):

- Capital costs: Grant from Peatland ACTION covers 50% of the capital works costs (typically £1500 per hectare) remaining £750 per ha must be met through private finance or forward sale of carbon units.

- Maintenance costs: Maintenance costs to be fully met for the first 10 years by grant funding in the region of £15-20 per hectare per year at current prices.

- Carbon revenue: Revenue from sale of carbon units awarded through the Peatland Code.

- Private finance: Upfront finance required to meet 50% capital cost can be met by the forward sale of carbon units or by accessing a private finance facility (potentially supported or managed by Scottish Government).

- Profit: Potential for upside. Any carbon revenues not needed to repay private financing for initial 50% capital costs and Peatland Code costs (for registration, validation and verification), and any additional maintenance costs after the first 10 years of the project would be profit.

- Risk: Liability for 50% of initial capital costs (typically £750 per ha, known at outset) and peatland code costs must be covered by sale of carbon units.

Scenario D: Peatland Code with guaranteed carbon price and public support for maintenance costs (Potential):

- Capital costs: 100% of capital costs met by a private finance facility (potentially supported or managed by Scottish Government).

- Maintenance costs: Maintenance costs to be fully met for the first 10 years by grant funding in the region of £15-20 per hectare per year at current prices.

- Carbon revenue: Revenue from sale of carbon units awarded through the Peatland Code.

- Carbon price guarantee: The Scottish Government guarantees a minimum price paid for peatland carbon to cover project costs, investor repayment and ensure the project’s economic viability. If carbon prices are above the minimum carbon price guarantee, the project can benefit from the upside by selling its carbon credits directly in the market.

- Private finance: Upfront finance required to meet 100% capital cost can be met by the forward sale of carbon units or by accessing a private finance facility (potentially supported or managed by Scottish Government).

- Profit: Potential for upside.

- Risk: The minimum price guarantee substantially reduces financial risk.

For respondents with more knowledge/interest, if there is sufficient time, interviewers may wish to get feedback on preferences for a floor price versus contracts for difference mechanism as part of the last scenario:

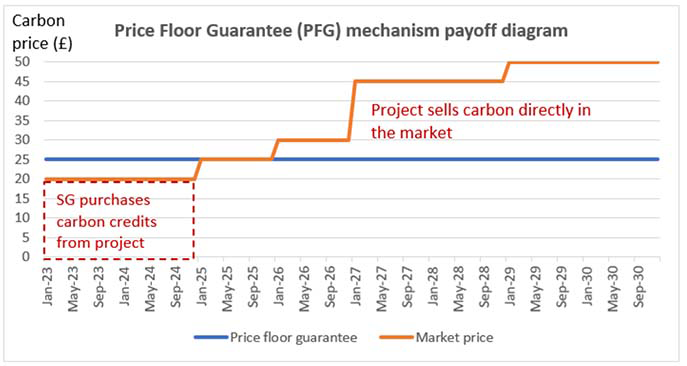

Price Floor Guarantee: Scottish Government guarantees a minimum price or “price floor” which provides projects with a minimum guaranteed income for their verified peatland carbon units. Peatland carbon projects may still sell their carbon in the market, if the market is able to pay higher than the price floor. However, if market prices decline below the price floor, projects are guaranteed a sale to a guarantor (which may be the Scottish Government) at the value of the price floor. Refer to exhibit below for an illustrative payoff diagram of the financial mechanism.

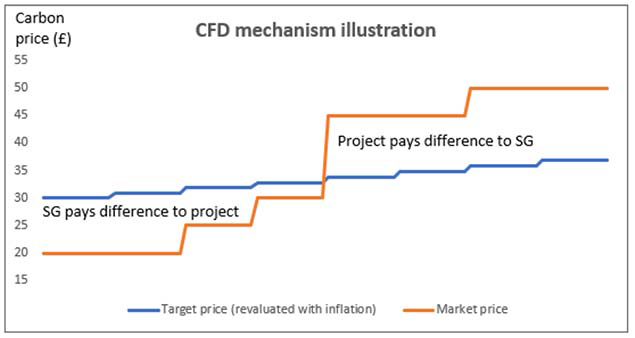

Contract for Difference: A "target price” for carbon is set by Scottish Government, based on an auction or market prices at the time (and potentially revaluated in line with inflation). Prices may differ for different types of project, depending on the range of costs and benefits associated with types of location or restoration.

- If, based on market prices at the time, the project has to sell its carbon for less than the “target price”, Scottish Government pays the difference to the project.

- If the project sells its carbon for more than the “target price”, the project pays the difference to Scottish Government.

Participants were also provided with the following information for each of the four scenarios:

Carbon revenue estimated to be around £40-70 per hectare per year on average at current prices but could significantly rise or fall.

Project validation cost ranges from £1,500-2,500, depending on the size of the project.

Registering with the Land Carbon Registry is a one-time payment of £400.

Peatland Code projects are verified at year 5 and then at least every 10 years. Each verification costs about £2,000.

Long-term maintenance costs of restored peatland are estimated to be ~£15-20 per ha per year but could rise and fall depending on a range of factors.

The following questions were asked about each of the four scenarios:

Individual How well does this finance mechanism fit with your personal priorities (business, resource, capacity etc), views and values?

From a personal or business perspective, how well do you think this kind of finance mechanism would work for you or businesses like yours?

How risky do you think this finance mechanism would be for people like you?

How confident would you feel about signing up for this kind of finance mechanism? (why / why not?)

Social

In general, how do you think other land owners/managers would feel about this kind of finance mechanism? (why?)

In general, how well does this finance mechanism fit with the needs and priorities of land owners/managers? (why?)

Additional questions related to the proposed finance mechanisms

INSTRUCTIONS FOR INTERVIEWER: If you can see a risk of over-running the maximum duration of 60 minutes for the interview at this point, skip this section. If you recognise this risk part-way through this section, skip any remaining questions.

QUESTION FOR INTERVIEWER: Is there enough time remaining to continue with this section? (i.e., no more than 50 minutes into the interview at this point)

- Yes (continue with this section)

- No (Skip to final page)

Have you encountered any useful sources of advice, information or guidance about peatland restoration? (Y/N/Unsure/Don’t remember)

[If yes] What are the most useful sources of advice, information or guidance that you have informed your thinking about peatland restoration? [open question]

Why have these sources been useful?[open question]

Are there topics relating to peatland restoration where you would like more or better advice, information or guidance in future? (Y/N/Unsure)

[If yes] Please list the topics and explain [open response]

Have you experienced any issues around how peatland carbon markets interact with agricultural support schemes that you would like to see addressed in the design of future support? I[open question; prompt: this may include for example issues around the timing and sequencing of funding from Peatland Action and the Peatland Code]

If unrestored or degraded peatlands became subject to tax or financial penalties, how might this affect your peatland restoration plans? [open question]

If suitable markets were available, might you be interested in selling other types of credits that the restoration of your peatlands could potentially generate, for example biodiversity uplift or flood mitigation? Why or why not (e.g., what are the main risks, issues, opportunities for you)? [open question]

Closing and Re-contact Consent

‘Thanks so much for your time and for contributing to this research. I have completed my questions now. Is there anything that you would like to add about any of the topics we have discussed in this interview? [open response]

We don’t have plans right now to follow up with any further questions, but would you be open to us contacting you again in future to invite your participation in research on related topics?’ (Y/N)

[If Yes] What would be the best way of contacting you for any future invitations?

- Phone

- Other

[Based on answer, confirm the contact details already held for the person are correct, or request that information].

[Interviewer to thank the participant for their contributions and let them know what happens next with their compensation payment]

Contact

Email: peter.phillips@gov.scot

There is a problem

Thanks for your feedback