Overcoming barriers to the engagement of supply-side actors in Scotland's peatland natural capital markets - Final Report

Research with landowners and managers in Scotland to better understand their motivations and preferences to help inform the design of policy and finance mechanisms for high-integrity peatland natural capital markets.

5 Findings – Feedback on the scenarios

This section is dedicated to each of the four scenarios, presenting their key components and respondent perceptions around the clarity, appeal, risks and suggested improvements.

5.1 Current scenario A: Peatland ACTION only

Overview: This scenario presents a currently available opportunity for supply-side actors to engage in peatland restoration. In this scenario, 100% of the capital works costs are covered upfront by Peatland ACTION grants, with long-term liability of maintenance costs covered by the landowner / manager. Given no carbon units are generated in this scenario, the project is under no obligation (Peatland Code or otherwise) to maintain the site beyond the initial 10-year requirement that Peatland ACTION requires, from the date of the final grant. Therefore, the risk of the site degrading over time is considered high (see the Scenarios section under Methods Overview and Table 5 for more details on this scenario and its assumptions).

Key scenario components:

- Peatland ACTION – grant funding supports 100% of capital works costs only.

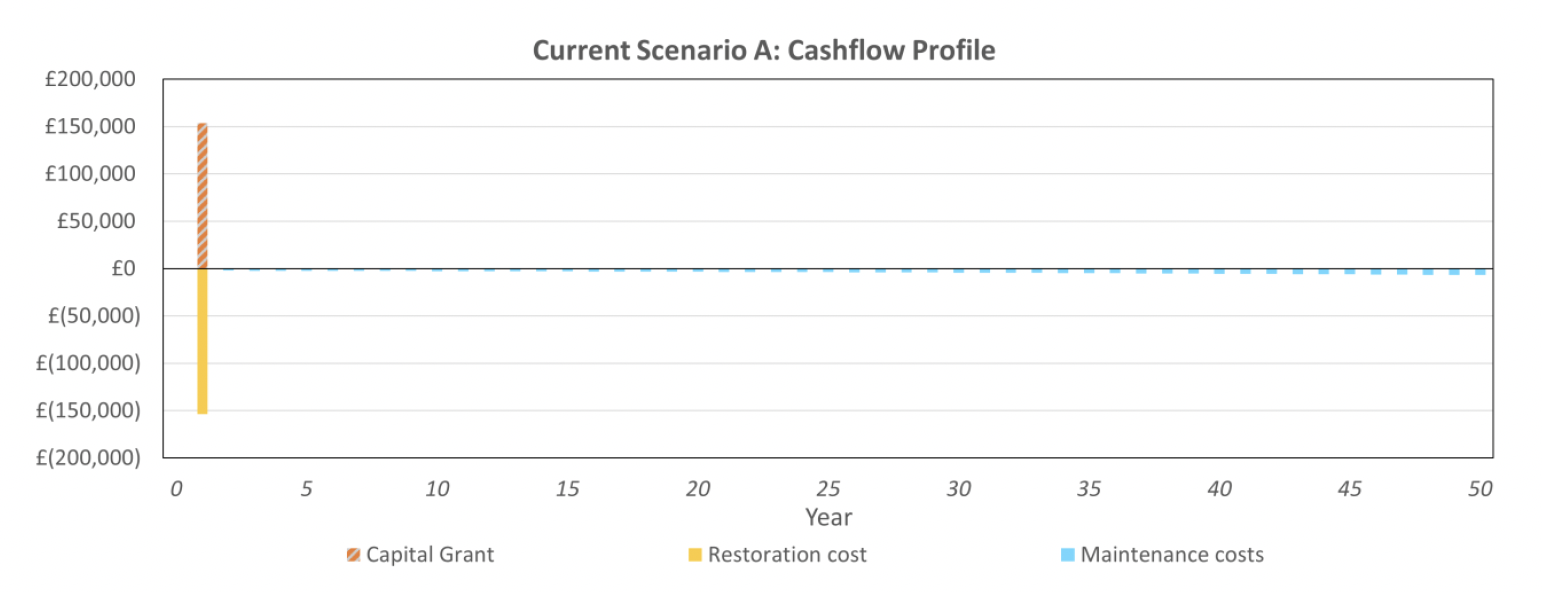

Net operating cash flow: Minus £43,000, discounted at a rate of 6%, with this being the sum of HMG's Green Book Rate of 3.5% and modelled inflation rate of 2.5%.

- Net operating cash flow is a measure of a project's ability to generate cash over time. It can be used to assess a project's ability to cover its lifetime costs. In this scenario, the net operating cash flow is negative, hence the project is not able to cover its lifetime costs (Figure 4).

- While the cash position is negative, restoring peatlands still create carbon savings and other ecosystem services, despite not converting to carbon credits. The resulting benefits to society are real and quantifiable but not monetised for project owner.

Key considerations for the project owner: The project owner must cover uncertain long-term (50+ years) maintenance costs using their own funds which creates a funding liability.

Key considerations for Scottish Government: The NPV of the cost to the Scottish Government is minus £137,000 (corresponding to the Peatland ACTION grant provided to cover upfront restoration costs and equivalent to £1,500 per hectare).

The project is high risk because of the unfunded maintenance liabilities and the absence of contractual obligation to maintain beyond year 10. As a result, the site condition might degrade over time after the restoration has been completed.

Clarity of the scenario: When participants were asked to indicate how clear the scenario was to them, on a scale of 0 (not at all clear) to 100 (extremely clear), the mean rating was 78.78, indicating a relatively high level of clarity. The spread was large with a minimum score of 19. However, in stark contrast to the high clarity scores, the mean attractiveness rating was 37.57 on a scale of 0 (not at all attractive) to 100 (extremely attractive) (n=42). This implies the scenario is easy to understand, but not very appealing to landowners.

Alignment with personal values: When asked if 'this scenario aligns with my personal values', the mean response was neutral (3.92 out of 7). While a slight majority of respondents (40%) felt that the scenario aligned with their personal values, others did not (31%), indicating that the Peatland ACTION only scenario may be somewhat divisive in terms of personal values alignment.

Likelihood of adoption: When participants were asked if they would want to sign up to this scheme, with only 16% expressing strong or moderate agreement with the statement. On the contrary, a significant proportion of respondents (52%) expressed they would not. The results suggest that while there is some interest, this may be considered a niche scenario to sign up for, or other scenarios were more appealing. Reinforcing this point, when asked if they considered the scenario to be appealing to land owners/managers in Scotland, 57% expressed disagreement, again, suggesting other scenarios may be more appealing or potentially indicating a need for adjustments to the policy to increase its attractiveness to these stakeholders. This is significant because this scenario describes the business-as-usual option available to fund peatland restoration in Scotland. However, when supply-side actors are made fully aware of the cost profile and liabilities of the Peatland ACTION only scenario and have alternative options, it is not considered very attractive.

Nonetheless, 5% of participants strongly agreed with the statement, again implying there is a niche where some landowners would consider it very appealing to sign up to.

Attractiveness of the scenario

In stark contrast to the high clarity scores for this scenario, the mean attractiveness rating for the Peatland Action only policy scenario was 37.57 on a scale of 0 (not at all attractive) to 100 (extremely attractive) (n=42). The median and mode were both 50/100. The standard deviation was 24.95/100, indicating substantial variation in the response pattern. Continuing on from this, 56% of the respondents expressed some degree of agreement that the scenario was a poor fit for their financial circumstances (with 25% strongly agreeing), with future obligations and potential burdens of ongoing costs after the initial restoration cited as financial issues.

The remainder of this section provides an analysis of qualitative feedback on the scenario, and how it might be enhanced, based on data from surveys, interviews and workshops.

Demand was niche but highly valuable for those who cannot trade carbon

The positive responses tended to be people alluding to other groups that might see this as a good option, rather than reflecting on their own situation. Of those who answered this way, charities, NGOs, philanthropists or environmental groups tended to be their focus:

"Yeah, only if there is some kind of sufficient altruistic angle, in general there is minimal out there unfortunately" (Participant 32)

However, two participants saw this as a good fit. Firstly, one was a crofter, who chose this scenario due to personal principles and ethos towards land management:

"Certainly [this scenario] was the one I identified with from a local crofting level, my own croft, and what we try and do with the land" (Participant 13)

The second was a staff member of a charity with an environmental focus. They saw the value in the simplicity of the scenario, the assistance provided from Peatland ACTION and being able to avoid carbon credits:

"We have a lack of capacity in terms of staff, [so] that is quite an attractive option. Plus, … our senior management haven't decided whether we want to go with carbon credits … how ethical it is. That means with this option, we could just get on with the work and deliver biodiversity and carbon sequestration objectives." (Participant 24)

Another participant considered it a good fit as they were "unsure how the finances work" (Survey response) in latter scenarios. It was seen to be a "simple and straightforward" (Participant 11) process, and it was perceived as positive in that there are no ongoing (multi-generational) agreements beyond the maintenance. It seems that the participants who held this opinion had relatively accessible sites with no severely degraded peat, where ongoing maintenance would be minimal:

"The simplicity of the first one appeals; you did the work, it is all paid for, and your only worry is, "are we doing the maintenance correctly". You are not worrying about … selling carbon credits." (Participant 2)

The upfront capital costs help to mitigate risk and get projects off the ground for those who may not be cash-rich, such as charities, owners of small (potentially amenity) land, or crofters:

"It is not so much risk in terms of whether the project is going to work; it is not really a big risk because Peatland ACTION itself works really well, the funding, and they give you the capital costs, so it is not the risk that put us off" (Participant 22)

So overall, despite very few participants agreeing that this scenario was appealing to them, there does appear to be two groups who might take this option going forwards – NGOs/charities and crofters. This option would help to overcome initial hurdles and get more projects from these groups underway.

Negative or unattractive aspects

It was clear from both quantitative and qualitative analysis that this scenario was considered a bad fit for the majority of participants, for example, those who owned their land, but were cash poor. Companies did not like this option either, because they could not show profits to shareholders and the scenario results in an overall loss.

The clearest negative aspect of this option (compared to all the other scenarios) is there are no ongoing carbon payments associated with it. These carbon credits would be useful to cover the ongoing (and unknown) maintenance costs, or, as the following interviewee explains, to inset their own activities elsewhere:

"I think every client I have is looking at it for the generation of carbon credits … to sell units or to inset … against their portfolio. … I don't think there is many farming clients or ours that would be happy to do a project with no future revenue." (Participant 7)

Interestingly, while lack of carbon finance is seen as unattractive by some, one respondent points out that the "absence of the carbon standard does mean that there are no validation/verification costs etc... which could mean this is a lower risk over the long term as liabilities are reduced" (Survey response).

The second clearest theme was that the maintenance costs were not covered by the grant. This concern suggests that the lack of guaranteed support for maintenance and upkeep could discourage some landowners from pursuing restoration projects:

"The big unknown is … what is involved in the management and maintenance of it. Is it walk round the site once a year and go, "oh that looks ok"? Is it walk round the site once every five years and go, "well I hope that's ok"? … not actually knowing what the technical expectation is." (Participant 2)

More negative sentiments were aired from a farming participant, who decided to act swiftly in restoring their peatlands, to then feel disappointed later, when newer options included carbon payments:

"It has earned nothing, there is no income from it, which is quite annoying. It doesn't fall into the agricultural support mechanism, it may do in the future, but at the minute, it doesn't" (Participant 12)

The data suggest that while some aspects of the scenario may be appealing, there are several significant concerns that could make it less attractive for many landowners and managers in Scotland. These include the potential for ongoing maintenance costs, the lack of revenue / profit potential compared to carbon market opportunities, and the need for more incentives or financial support.

Risks involved in this scenario

In terms of individual survey responses, a significant number of participants (48%) expressed some level of agreement that the scenario is too risky, with 20% strongly agreeing. On the other hand, the largest single category was neutral, selected by 30% of respondents, again suggesting that if they were not considering this option, then they would also not consider the risks involved, described by the following participant:

"Yes, it is a negative return, so the risk is almost irrelevant, it is not a financially sensible decision." (Participant 16)

As discussed above, the biggest risk that participants saw was "the risk of future costs associated with maintenance and uncertainty over other future land uses" (Survey Response).

One additional risk that was highlighted by three separate participants was around deer management, and how this might incur maintenance costs to rise:

"Our neighbour has extremely high deer numbers. I am concerned about the deer tracking over some of the restored peatland and that might require some real ACTION if more erosion starts occurring." (Participant 11)

Farmers were one group that considered this option a risk, as conserving peatland clashes with the management of the farm unit:

"Farmers, to the best of my knowledge, are not going for this because there is a management risk and there is a financial risk, simple as that." (Participant 10)

One additional response touched on the operational risk of potentially causing more harm through intervention:

"I find the idea of intervention a bit risky in case doing something is worse than doing nothing." (Survey Response)

It should be noted that this scenario places the lightest obligation to maintain a peatland project in good condition on the project owner out of the four scenarios in this research. As a condition for the funding the capital works of restoration, Peatland ACTION requires the restoration to be kept in place for a minimum of 10 years, with any costs associated with this maintenance being the responsibility of the project owner. Ideally, though, the peatland would be kept in good condition permanently, such that the sequestered carbon stays trapped in the restored and healthy peatland.

Making the scenario more appealing

Beyond participants suggesting that carbon credits should be included (which are available in the other three scenarios so will not be discussed here), other suggestions were made to improve the scenario. One of the most salient themes was that the scenario needed to consider cross-boundary agreements more, and the equity of these arrangements, particularly for crofters on common grazing:

"So, we are hoping … to be working with [Public Organisation] who we share a large boundary with, sharing the contractor to do some of that work and then hopefully the same for the private landowner who shares another of our boundaries. So, facilitating that kind of work is really important to making this kind of thing efficient and effective on the ground." (Participant 11)

"It would have to be an equitable model across those that have a direct share, but also anybody that … has access to use the land. … Depending on how you are using the land - if that is having a greater impact on the work, then that would be the old user pay model." (Participant 3)

Another theme was for the scenario to provide more details around ongoing maintenance costs and to potentially implement a tiered approach. Here, if the maintenance costs were predicted to be low then an entry level grant could be applied for. However, if the site was more complex or the peat was heavily degraded and frequent maintenance was required, a basic grant with ongoing capital released to ensure the project succeeded might be more appealing and increase uptake.

Some respondents suggested that the scenario could be made more attractive by providing more detailed information about the conditions of the grant (including land use restrictions) and how to secure it. As one participant pointed out:

"There is no explanation … of what the conditions of the 100% grant are (there are always conditions!) and also no explanation of how to get to the position of having a grant in place. Without the prior knowledge … this information would be helpful". (Survey Response)

5.2 Current scenario B: Peatland ACTION and Peatland Code

Overview: This scenario builds on current scenario A (above) by introducing carbon revenues, and long-term contractual commitments through the Peatland Code, to support the long-term maintenance costs of the project (see the Scenarios section under Methods Overview and Table 5 for more details on this scenario and its assumptions).

Key scenario components:

- Peatland ACTION – grant funding supports 100% of restoration costs as an upfront payment.

- Carbon revenue – carbon credits generated through the Peatland Code are sold upon verification (5-year cycle) to fund long-term maintenance costs.

- Private finance – there may be a small requirement for private finance (c. £20,000) to cover maintenance costs between Years 1 and 5 before the first verified carbon units (PCUs) are generated and sold in Year 5. In addition, costs related to project development (pre-restoration) process under the PC are not eligible for Peatland ACTION funding and therefore may also require upfront private finance.

The use of private finance entails financing costs (i.e. the private investor will require a rate of return in exchange for its participation). Table 6 shows what Internal Rate of Return (IRR) an investor could achieve based on a certain carbon price and inflation-linked lease payment made to the landowner. Investors typically have IRR requirements correlated with the level of risk of the investments that they are making. Peatland restoration is likely to be considered high risk given the nascency of the market and lack of track record of successful repayable investment, therefore, investors are likely to require higher rates of returns to invest in this type of opportunity. Under the base case assumptions, with a carbon price of £30, an investor could pay annual inflation-linked lease payments of £50 per hectare and achieve an IRR of 15%.

| PCU price (2% real annual growth) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IRR | 10 | 20 | 30 | 40 | 50 | 60 | 70 | 80 | |

| Inflation-linked lease payment per hectare p.a. | 0 | 12% | 26% | 37% | 45% | 52% | 59% | 64% | 69% |

| 50 | <0% | 8% | 15% | 22% | 28% | 34% | 39% | 44% | |

| 100 | <0% | 0% | 6% | 11% | 16% | 20% | 25% | 29% | |

| 150 | <0% | <0% | 1% | 6% | 9% | 13% | 16% | 20% | |

| 200 | <0% | <0% | <0% | 2% | 5% | 8% | 11% | 14% | |

Note: Internal Rate of Returns (IRR) are dependent on a range of factors including but not limited to carbon prices, cost of restoration and maintenance and carbon unit generation rate. The figures in Table 6 are illustrative only and not meant to represent any existing project.

IRR <5%

5% <= IRR < 15%

15% <= IRR < 25%

IRR >= 25%

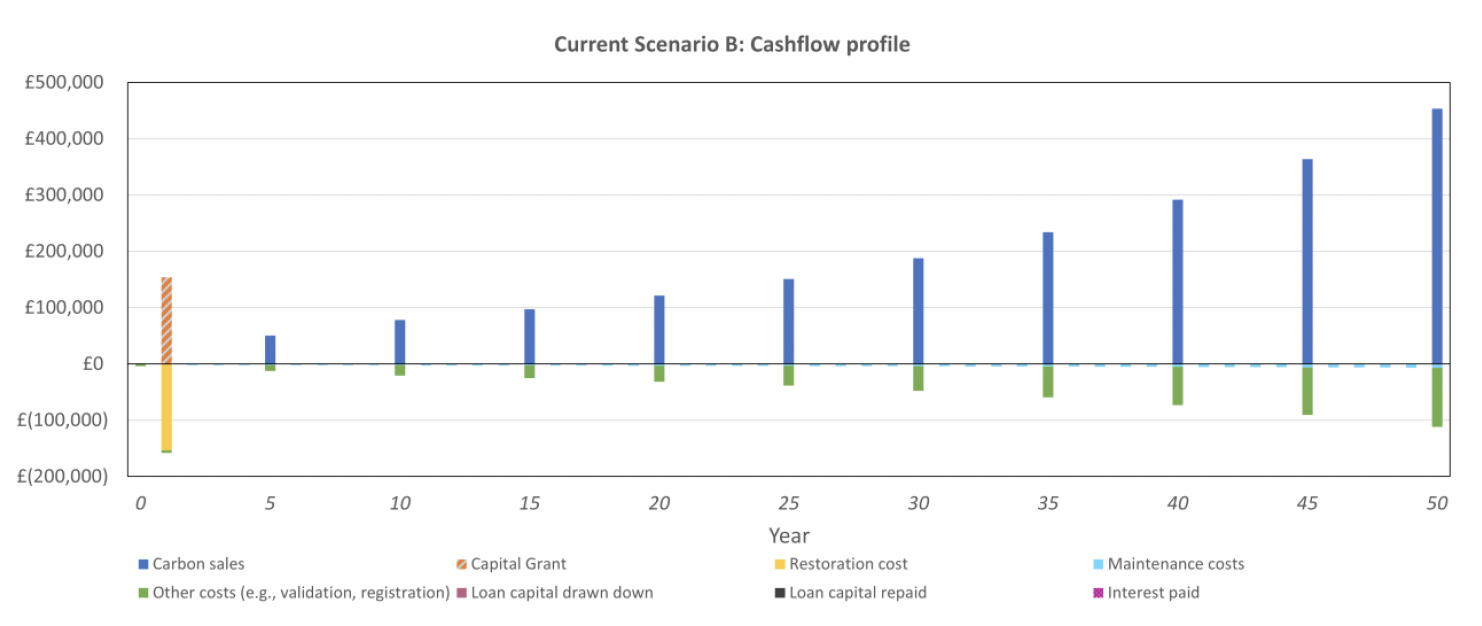

Net operating cashflow (6% discount rate): £193,000 (Figure 5).

Key considerations for the project owner: The project owner is exposed to changes in carbon prices and project maintenance costs. Should carbon prices rise, there is an opportunity for the project developer to benefit from the upside by selling credits that are verified over time. Should the price of carbon decrease, the project might not generate sufficient revenues to cover its costs or maintenance liabilities.

Key considerations for Scottish Government: The NPV of the cost to the Scottish Government is minus £137,000 (corresponding to the Peatland ACTION grant provided to cover upfront restoration costs and equivalent to £1,500 per hectare).

The project is less risky than in current scenario A because the carbon revenues can be used to fund maintenance costs and the Peatland Code agreement contains a contractual obligation to maintain the project site. As a result, the project site condition is less at risk of degrading over time after the restoration is completed.

Clarity of the scenario: The respondents' perceptions regarding the clarity of the scenario were tested (scale of 0 to 100), with a mean (average) score of 70.56. This suggests that, on average, respondents found the scenario moderately clear and showed a reasonable understanding based on the description provided. It's worth noting that the mode was 100 out of 100, which indicates that a notable segment of the respondents found the scenario extremely clear.

Alignment with personal values: Regarding the statement, 'this scenario aligns with my personal values', 49% agreed (6% strongly agree; 23% agree; 20% somewhat agree) while just 19% disagreed (11% strongly disagree; 3% disagree; 6% somewhat disagree). 31% (n=11) remained neutral. The median, mode, and mean (4.37 out of 7) responses were all neutral, indicating that, on average, respondents did not feel strongly about this scenario, with a slight inclination towards agreeing. Results were very similar when asked if the scenario fit their financial needs.

Likelihood of adoption: When respondents were asked to evaluate the statement 'I would be keen to sign up to this scenario', 69% agreed to some extent (3% strongly agree; 19% agree; 47% somewhat agree [n=15]). The somewhat agree category was both the mode and the median (n=32), therefore most respondents are generally inclined towards agreeing, but with reservations. However, when considering the statement 'In general, I think this scenario would be appealing to land owners/managers in Scotland' more widely (beyond their own land) the mean response fell into the somewhat agree category (4.85), indicating a general trend of partial agreement among respondents. While there was a tendency towards agreement, there were varying opinions about the appeal of this scenario. It is noteworthy that a considerable portion, 28% (n=11), opted for a neutral stance, suggesting some degree of uncertainty or ambivalence about the scenario's potential appeal.

Attractiveness: The mean attractiveness score was 61.38 out of 100 (n=34). This result indicates that, on average, participants found the scenario somewhat attractive. The median score was 61.5 which is very close to the mean, suggesting that the data are reasonably symmetrically distributed. Furthermore, the mode was 70, implying that a considerable number of respondents found the scenario relatively attractive. However, the range of 90 (from 0 to 90) shows that there were diverse views on the attractiveness of the scenario. Some respondents found the scenario not at all attractive, while others found it extremely attractive.

Fit with financial needs: The results signalled an ambivalent response to whether this scenario met their financial needs. The median and modal responses indicated a neutral stance with scores of 4 out of 7 (n=31). At 3.87 out of 7, the mean (average) response was slightly below the mid-point, suggesting a slight leaning towards disagreement with the negatively-coded statement. The standard deviation was 1.65 out of 7, indicating a moderate spread of responses.

A narrow plurality of respondents remained neutral (26%, n=8), indicating uncertainty or ambivalence towards the financial applicability of the scenario. This is followed by a near equal split among those who somewhat disagreed (23%, n=7), disagreed (19%, n=6), and the combined sum of those who strongly agreed (10%, n=3), agreed (10%, n=3), and somewhat agreed (10%, n=3). A very small percentage of respondents (3%, n=1) strongly disagreed with the statement, indicating they didn't find the scenario a poor fit with their financial needs. In total, the question saw 31 responses.

The remainder of this section provides an analysis of qualitative feedback on the scenario, and how it might be enhanced, based on data from surveys, interviews and workshops.

The attractiveness of carbon credits to provide new revenue streams

During interviewing, a significant number of participants (13) indicated that this scenario was their preferred option. This might have been due to the scenario being a currently available option to participants (as opposed to being hypothetical). Nevertheless, there were still clear themes emerging as to why this was their preferred choice.

Some respondents found the scenario attractive because it facilitated initial restoration work, which is capital-intensive. There was hope that the scheme could "offset the capital risk and provides an opportunity to earn revenue in the future" (Participant 5).

The "scope for income generation" (Participant 2) from carbon credits would be attractive to help meet existing management arrangements or would be invested back in the business:

"Any money I make … gets fully invested in the farm. … If there is money from the peatland that would be very welcome." (Participant 23)

A farming participant cited pressure on farm incomes as a reason to explore peatland restoration as a means of diversification:

"The whole reason why we are having to diversify is because you don't make a huge amount of money in farming and the bank balances aren't always as good as we would like them to be." (Participant 38).

However, another farmer had more nuanced views:

"The notion of farmers being paid for looking after peat is not something that aligns with my own personal views. However, taking into account the political objectives of the current government, I would consider undertaking the said works in order to create a new source of income." (Survey Response)

This comment represents a pragmatic approach, demonstrating that despite personal value misalignment, financial considerations and political realities could influence decisions. Similarly, a sentiment among several survey respondents was the balancing act between generating income and ensuring responsible land management. As one respondent put it, the scenario would enable them to "provide income whilst doing the right thing by the land."

To some NGO landowners (although not exclusively, as explored later), the potential to have income that was not restricted to a specific purpose was attractive:

"From a [NGO] point of view a carbon income is very useful because it is not restricted to a particular workstream." (Participant 11)

"Being a charity, to be able to sit on money and have it available as-and-when is [beneficial]. … Going with the PIUs rather than the actual carbon credits has helped cash flow." (Participant 25)

Two participants involved in an advisory role considered that this scenario was likely to be the best option forthcoming and that they actively advised their clients to take it up:

"We are in a unique position, at the moment, where you can get 100% of the capital costs for restoration and you make a profit out of carbon credits. If you are going to do peatland restoration, now is the time to do it … In the past, it was just a grant and in the future it will be maybe just the carbon credits." (Participant 22)

The attractiveness of carbon credits to inset against other activities

Not all participants wished to sell carbon credits and instead wished to retain control of these. This was particularly important to some participants who wished to wait and see how the market would develop (or to be banked for future carbon insetting):

"Even though we have an upfront cost, we retain full control of the carbon afterwards. … We haven't decided whether we would use it ourselves or whether we would sell it, we just want to quantify the carbon initially." (Participant 34)

"As farming businesses, we also try to strive to be carbon neutral so do we want to actually keep some of our carbon credits for our own carbon bank balance?" (Participant 38)

Similar sentiments were expressed by one estate manager, who voiced concern for their carbon footprint (South of Scotland Workshop).

The complexity of the scenario was off-putting or daunting

There was a perception among some participants that there was a high knowledge requirement or there was an administrative burden due to the "convoluted process of applying" (Survey Response):

"If I was to be faced with putting an application in for the Peatland Carbon Code by myself … I would probably just give up because it is onerous and complicated." (Participant 11)

"We ended up working with [Agent] who did all the work for us, so they set up an agreement with us, took all the PIUs, bought them from us, so we don't have to deal with any of the validation, verification, all that kind of process … there is a lot of knowledge that is needed to go through that." (Participant 25)

One agent/advisor affirmed that contracting entailed a "high knowledge requirement on the part or landowners" (Participant 32).

This line of thinking was extended when considering the complications associated with validation and verification through the Peatland Code. The intricacy of merging two financial mechanisms and the resulting uncertainties appear to deter the respondents. A survey respondent stated "It is less attractive as it is very complicated to blend the two finance mechanism and many types of restoration project are either not eligible or economically viable under Peatland Code." Another stated "[The] only unattractive aspect is complication of validating/verifying through the Peatland Code". Especially during the workshop held in the South of Scotland, a key conclusion from participants was that if this mismatch was resolved then uptake of projects would be drastically increased.

A Peatland ACTION Project Officer expressed his concern with combining two sources of funding, remarking, "It is very risky … to deliver restoration as the time delays in dealing with the Peatland Code in combination with Peatland ACTION has delayed a number of projects we have worked on." (Survey Response) The complexities involved in this scenario has placed "considerable strain on Peatland ACTION capacity, possibly unfairly so" (Survey Response), hinting at potential issues of sustainability and scalability.

Smaller landowners thought the cost and effort of achieving Peatland Code registration and validation seemed disproportionate to their circumstances:

"We are really at the small end. … It makes no sense whatsoever for us. I can see the need for the registration and verification but whoever designed it was not thinking about incentivising small crofters" (Participant 20)

This sentiment was expressed by multiple participants who saw verification and validation to be costly, both financially and through time invested:

"I couldn't commit to this financially as it would be impossible to sustain. I would be better not registering, trying to do the best thing by the peatland myself without thinking about paying out for verification every five years into the future." (Survey Response)

Suggestions from participants on how to improve to this aspect of the process and make the scenario more financially attractive included:

"Increased verification events (at lower cost and more efficiently delivered) is key to delivering a commercially attractive product to the market." (Survey Response)

"Project can be validated after works have started, providing there is sufficient evidence through a feasibility study." (Survey Response)

Carbon markets are embryonic and agreements are lengthy

Several participants highlighted that it would not fit their circumstances due to critical perceptions on the risks of carbon trading. This scenario was the first option to include carbon credits, therefore the first-time participants discussed their opinions of this subject. Many of these sentiments also apply to later options which also include a carbon trading element, which may not have been discussed in those latter scenarios.

Some participants were unsure as to the reputational kick-back they may receive for engaging in carbon trading, with some airing ethical concerns:

"I mean again when you are talking about values and things like that, I do struggle quite a lot with the whole ethics of carbon trading." (Participant 11)

The length of the agreement was seen as highly risky and entirely inappropriate for some people:

"A 50-year agreement is beyond anything that I have experience of … if it all goes horribly wrong … you are saddling a future generation." (Participant 10)

Expanding on this, the agreement was "too restrictive" with an advisor suggesting they would avoid telling clients to sign a 50-year contract without a break clause (Participant 17). Participants provided examples of external and unanticipated events that could occur over that long timeframe which could affect the restoration:

"You are signing up for a project which you are committing to for the long-term whereas the effect of climate change could actually make committing to that … difficult." (Participant 36)

"Why would you take the risk of going into carbon trading scheme where some large company could hold you personally responsible for a fire that was lit by somebody else?" (Participant 1)

Participants suggested measures such as a price floor (discussed in potential scenario B) could make the scenario more attractive.

Unknowns are perceived as added risk

When asked about how risky the scenario was during the survey, 21% (n=7) of people held neutral opinions (mean was 3.88 out of 7). 9% of respondents (n=3) strongly agreed, another 9% (n=3) agreed, and a further 18% (n=6) somewhat agreed that the scenario was too risky for them, indicating a moderate level of risk perception. However, not all respondents shared these concerns, with a significant 24% (n=8) disagreeing that the scenario was too risky, with another 18% (n=6) somewhat disagreed.

Some respondents referred back to the complexity of assessing the risks involved, for example, saying it is "too difficult to understand and appreciate the risks", or, "I doubt many advisors know the intricacies, let alone provide advice on these risks" (Survey Responses).

The largest unknown was the size of maintenance costs, which were unfunded in this scenario. While carbon credits could be sold to generate revenue, some participants saw significant uncertainty around unknown maintenance costs, especially if carbon revenues fell to below future maintenance costs: "the entire debate is so sensitive to the price of carbon which is a complete unknown" (Participant 32). One participant thought this the uncertainty would be a dealbreaker:

"You are relying on a carbon credit market to fill the funding gap. … From an owner's perspective you are at risk for the deficit and if your only way of funding it through the sale of carbon credits, which you may or may not get at a certain price … that is not a risk that they would take" (Participant 28)

Another unknown resulting in increased risk was that the regulatory environment could change in future, for example if there was to be a future requirement for insetting:

"I think people naively think that they don't have much of a carbon footprint, but they are still running a tractor, herd of cows, using fertiliser, all these things are emitters." (Participant 31)

Reflecting multiple risk factors, participants perceived that there was a risk to forward selling carbon and one agent noted that they advised clients to retain credits until units were verified:

"I think the minimum verification is at year 5, year 15, so it is those trigger points that we would probably advise clients if they were wanting to sell, rather than each year." (Participant 7)

Where there is shared responsibility of the land (tenanted farmers or crofters for example) then the assessment of risk becomes even more challenging:

"If you owned the whole place … and you are 100% in charge of the management and you take the risk to do something that is fine but we … and taking the risk on behalf of other people i.e. our shareholders and that makes it much more challenging." (Participant 1)

5.3 Potential scenario C: Peatland ACTION and Peatland Code with public support for maintenance costs

Overview: This Scenario proposes a partial restructuring of the Peatland ACTION grant, with 50% of the upfront Peatland ACTION restoration grant transferred to cover the first 10 years of maintenance costs (see the Scenarios section under Methods Overview and Table 5 for more details on this scenario and its assumptions).

Key scenario components:

- Peatland ACTION – upfront restoration grant reduced to cover 50% of upfront restoration costs.

- Maintenance payments – a portion of Peatland ACTION funding is restructured as fixed annual maintenance payments over 10 years.

- Carbon revenue – carbon credits generated through the Peatland Code are sold upon verification (5-year cycle) to support the liability of long-term maintenance costs.

- Private finance – the restructuring of the upfront restoration grant results in a upfront financing gap of c. £100,000 which could be addressed through the use of private finance.

The greater need for private finance in potential scenario C (compared to current scenario B above) implies higher capital costs.

| PCU price (2% real annual growth) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IRR | 10 | 20 | 30 | 40 | 50 | 60 | 70 | 80 | |

| Inflation-linked lease payment per hectare p.a. | 0 | 5% | 9% | 12% | 15% | 18% | 20% | 22% | 24% |

| 50 | <0% | 4% | 8% | 11% | 13% | 16% | 18% | 20% | |

| 100 | <0% | 0% | 4% | 7% | 10% | 12% | 14% | 16% | |

| 150 | <0% | <0% | 1% | 4% | 7% | 9% | 11% | 13% | |

| 200 | <0% | <0% | <0% | 1% | 4% | 6% | 8% | 10% | |

Note: Internal Rate of Returns (IRR) are dependent on a range of factors including but not limited to carbon prices, cost of restoration and maintenance and carbon unit generation rate. The figures in Table 6 are illustrative only and not meant to represent any existing project.

IRR <5%

5% <= IRR < 15%

15% <= IRR < 25%

IRR >= 25%

Under the base case assumptions, with a carbon price of £30 an investor that would pay annual inflation-linked lease payments of £50 per hectare would only achieve an IRR of 8% (versus 15% in current scenario B). Achieving a similar IRR of 15% with lease payment of £50 would require a starting carbon price of c. £60 (Table 7).

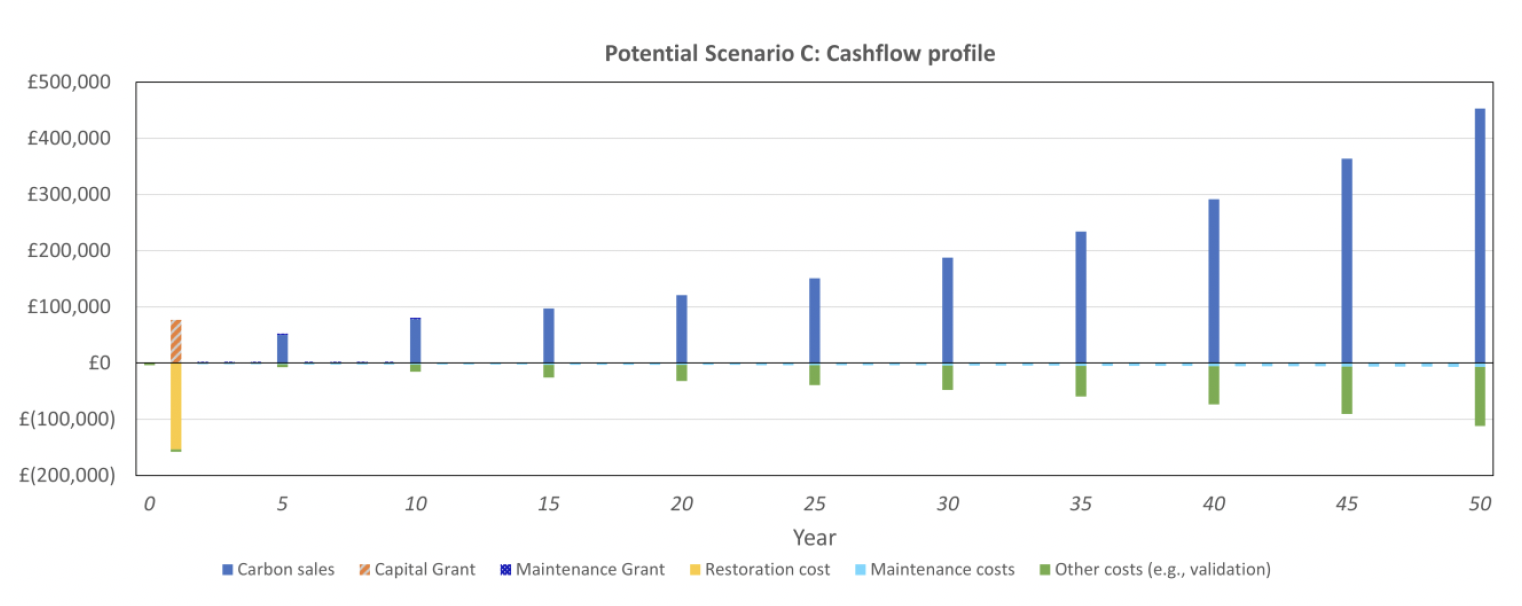

Net operating cashflow (6% discount rate): £145,000 (Figure 6).

Key considerations for the project owner: The provision of maintenance payments for the first 10 years of the project reduces delivery risk during this time, however, beyond this fixed term, the project owner remains exposed to changes in carbon prices and maintenance costs. Given the upfront financing need created by the reduced Peatland ACTION grant (50%), some of the project risk could also be shared with an external investor. It is worth noting that an investor would require a financial return and the landowner would have to share the value generated by the project with the investor. The project owner is exposed to changes in carbon prices and project maintenance costs. Should carbon prices rise, there is an opportunity for the project developer to benefit from the upside because it is selling credits that are verified over time. However, should the price of carbon decrease, the project might not generate sufficient revenues to cover its costs or maintenance liabilities.

Key considerations for Scottish Government: The NPV of the cost to Scottish Government is minus £68,000 (upfront restoration grant + maintenance payments, 6% discount rate applied).

The project is less risky than in current scenario A, because the carbon revenues can be used to fund maintenance costs and the Peatland Code agreement contains a contractual obligation to maintain. As a result, the project site condition is less at risk of degrading over time after the restoration is completed. Additionally, Scottish Government is contributing less grant money (than in current scenarios A and B) to the project and part of the project failure risk is transferred to a private investor, if the project owner decides to raise external private finance.

Clarify of the scenario: This scenario introduced participants to blended public-private finance for the first time. When asked about the clarity of the scenario, the median score was 75.5 (out of 100), indicating a high level of comprehension among the participants (n=28). The mode, or most frequently occurring score, was 100/100, which signifies that a notable portion of the respondents found the scenario extremely clear.

Alignment with personal values: When asked whether 'this scenario aligns with my personal values', 24% of respondents agreed, 30% disagreed and a notable 45% of respondents chose to remain neutral on this statement.

Likelihood of adoption: When asked if they would be keen to sign up to this scenario, 26% agreed, 54% disagreed, and only 19% remained neutral. This indicates that some of the participants who remained neutral when it came to their values decided they would not want to become involved in a scenario like this in practice. Concerning the statement, 'In general, I think this scenario would be appealing to land owners/managers in Scotland', 28% agreed while 39% disagreed, reflecting the findings above. In addition, 33% were neutral on this statement, potentially not wanting to assume other people's stance on the role of private finance.

Attractiveness: When considering the attractiveness of the scenario, the median score was at the mid-point of 50/100 (n=28) reflecting a balanced view among the respondents, further emphasized by the mode (also 50/100). However, there was a broad range of 93, spanning from a minimum score of 1 to a maximum score of 94 (out of 100), showing that the individual scores are widely distributed around the mean. Regarding the statement, 'this scenario is a poor fit with my financial needs', a considerable 50% of respondents agreed (including 17% who strongly agreed, 23% who agreed, and 10% who somewhat agreed), with only 19% disagreeing. Notably, 30% of respondents expressed neutrality on this particular statement. Again, this indicates that in practice the participants did not think this was a practical scenario for them, perhaps due to the considerable upfront costs, assumed to be filled by the role of private finance.

The remainder of this section provides an analysis of qualitative feedback on the scenario, and how it might be enhanced, based on data from surveys, interviews and workshops.

Attitudes towards the role of private finance were mixed

One of the biggest talking points during interviews and workshops was the role of private finance, with many mixed and differing personal opinions.

Many participants aired negative sentiments about investors in carbon offset markets. Smaller farming participants and NGOs explained how it did not fit with their ethos or "ethical compliance" (Participant 11) and suggested a power imbalance between investors and those delivering projects on the ground:

"Farming is all about being independent. Bringing in investors is completely foreign to my farming ethos which is all about being self-contained and standing on your own two feet." (Participant 10)

Participants explained how entering into a relationship with private investors did not suit their own morals, and were uneasy with helping large institutions claim to be carbon neutral:

"I am very wary of private investors … I don't want some big corporation to be thinking that they have dealt with the climate emergency because they have given money towards my peat being restored." (Participant 29)

"[I] only agree with private finance if this is coming from a reputable source with good green credentials." (Survey Response)

A general concern was that the relationship could prove extractive with financiers and the wider investment community standing to gain most:

"People with money are going to get more money and people with no money are not going to benefit" (Highlands Workshop)

Relating to the power imbalance highlighted previously, participants were concerned and raised questions about how to justify or prove unanticipated events ("deer numbers increase, [or] the land changes hands [or] say the peatland has not been restored properly (Participant 24)) to their private finance partners. Relatedly, participants viewed the complexity of such a relationship as being beyond their skills to navigate, and would need more guidance or training before feeling confident in committing to long-term changes in land management to comply with Peatland Code contracts:

"I would not have confidence to try and put that kind of a funding model together personally. I would have to put that out to an agent to do that for me at which point I feel as though I would probably lose a large amount of control." (Participant 11)

In contrast, some participants (albeit fewer) had positive perceptions of bringing in blended private investment. Firstly, some participants thought that significant sums of public money should not be spent on schemes that provide private gain to individual (private) landowners, and instead this should be the role of private finance:

"I understand this is the way it has to go, the government can't spend all of this money on restoration just for landowners to get free money." (Participant 22)

Some participants perceived that there was a "shortfall in public money" (Highlands Workshop) and pointed out how bringing in private funding is likely to help the Peatland ACTION money to go further and cover more projects, especially if a site is facing high costs.

One interesting insight relating to the above, was that private finance could help to fund the "low hanging fruit" – the easy to restore sites which give good results (in terms of carbon capture) – which come with lower risk and lower overheads, making them more suitable for private finance. Harder to access or heavily degraded peat could be tackled later through public investment:

"In the long term, the market is going to learn that difficult sites will have significantly worse outcomes … so the market will hopefully stop doing those sites and will align itself with easier good outcomes, that is probably where government funding needs to come in." (Participant 32)

It was perceived that bringing in private finance will also introduce increased scrutiny in terms of monitoring and maintenance, resulting in overall higher quality projects:

"A lower initial grant intervention rate could do a lot to bring in private finance earlier, which would have a knock-on effect where you have more [scope] to do really high-quality work." (Participant 4)

More than one survey respondent highlighted how this scenario was effectively forcing landowners to sell their credits, with fewer options to hold their credits for insetting purposes:

"An owner who did not wish to sell carbon units will be disadvantaged and meeting the 50% capex may be hard to justify in upland areas where earnings and return are typically low." (Survey Response)

"It is possible that livestock farmers will be taxed in the future for not being at net zero. … Farmers should not be encouraged to sell PIU's to opportunists that they may need themselves." (Survey Response)

Uncertainties over the role of private finance were also raised, particularly the uncertain relationship between Government and the banks, and/or, the landowner and the bank:

"When it becomes faceless private finance, I think there is real risk because civil servants and hardcore commercial getting into negotiations, it is not often civil servants that come up on top." (Participant 15)

Similarly, uncertainty was raised when dealing with a private company who may go bankrupt which would result in a landowner dealing with a new company who might not share the same ethos or alter the arrangement. Both quotes below suggest the Government is potentially a better third party to deal with:

"What happens if the company … all of a sudden goes bust, or gets taken over by another company who then starts trying to screw you down? I can imagine people being more comfortable about doing it through the Scottish Government who would then be seen as an honest broker." (Participant 31)

"One of the issues with doing it with a third party is counter party risk. Are they going to be there to maintain the maintenance obligations for the next 45 to 60 years? Or do they sell PIUs, cash out, and effectively leave us with all of that risk? Putting Scottish Government as the counter party [may] addresses those concerns" (Participant 36)

Conversely, one survey respondent suggested that "the long-term involvement of private finance [would] legitimise the marketable value of a carbon unit, rather than relying predominantly on grant funding", helping to overcome the uncertainties of the immature carbon market.

Maintenance fees are (partially) overcome in this scenario

Regarding maintenance costs (which were commonly raised as criticisms of the two current opportunity scenarios), some participants approved of the 10-year funding this scenario (hypothetically) provided for this ongoing task, firstly, to give the landowner the confidence/skills of how to do it, and secondly, to help with the overall quality of projects:

"[This] would be a really good scenario to encourage or to make sure people keep on top of that annual maintenance so they are carrying out their annual monitoring and surveying because it is a condition of the grant and, therefore, they will be more likely to do it" (Participant 25)

Unknown maintenance costs beyond the first 10 years were however raised again as an issue. These would need to be known before getting into an agreement with private finance over a loan. One person favoured the current (funded) surveying work of Peatland ACTION, which provides an initial estimate of costs, area that requires restoration, and maintenance costs, and was unsure if that service would be available under this scenario.

Risks involved in this scenario

In terms of perceiving the scenario as personally risky, 45% of respondents agreed (with 17% strongly agreeing, 14% agreeing, and 14% somewhat agreeing) and 24% disagreed (7% strongly disagreeing, 10% disagreeing, and 7% somewhat disagreeing). A substantial portion, 31%, remained neutral on the perceived risk of the scenario. These statistics were dramatized when asked about the risks to landowners in general, with an increased 54% agreeing (11% strongly agree; 26% agree; 17% somewhat agree) while 15% disagreed (3% strongly disagreed; 6% disagreed; 6% somewhat disagreed). A substantial 33% were still neutral on this statement.

Some of the risks provided during interviews, open-ended survey responses and workshops were also associated with previous scenarios, summarised as: length of commitments, uncertainty of future carbon markets/price and unknown maintenance fees which all introduced elements of risk. On maintenance fees, one participant thought this scenario would actually lower the risk of high maintenance costs appearing later in the project, due to effort put in upfront:

"I think because you providing 10 years' worth of maintenance contributions, that gets round the risk of the project failing, because you are pushed more into needing to do that maintenance work." (Participant 25)

Regarding specific risks that this scenario posed (as opposed to previous scenarios), firstly having to find 50% of the costs (or source private finance) introduced financial risk to them:

"Currently it is less risky because [Peatland ACTION] pay for all the capital costs so [landowners] are willing to give it a go. I think if you suddenly just gave them 50% of the costs then that might be challenging." (Participant 6)

One participant indicated potential risks with broker involvement, stating, "Brokers need to find clients to purchase PIUs. If they don't find takers the land owner/manager may not get the finance required. Who would pay then?" (Survey Response)

Making the scenario more appealing

Participants offered multiple suggestions on how the scenario could be improved. One participant suggested that the Government should be able to protect itself from paying maintenance costs if deliberate damage (or negligence) by the landowner occurred:

"What if, for example, the owner indirectly does some damage to the work - knock over ditches and stuff - that shouldn't be covered by maintenance, so there should be something in there that it protects the state's investment." (Participant 2)

Another participant suggested removing the public money altogether, to "get the joys of the free market as it were" (Participant 4). Similarly, another suggested lowering the 50% initial payment down, to allow for more private finance and less government money in cases which appear straightforward and achieve a high level of carbon capture. Another minor improvement to the scenario was suggested as paying for maintenance up to the first verification (rather than 10 years) so the landowner has experienced all stages of the process before being left to fund the project going forwards.

Another clear theme was around Peatland ACTION (or another institution) providing further guidance and definitions to help landowners fully understand the blended finance partnership agreements/terms of the loan from private finance. Additionally, clearer guidance on the responsibilities around monitoring and penalties for ill-practice were seen to be improvements, again, important to understand when a third party is involved:

"You need really robust ways of monitoring and very clear guidance because people will fight you in court as to say well you did the peatland restoration, you got all of this carbon money, it didn't work." (Participant 24)

One participant suggested that a collective fund (through which all private finance was administered) could help reduce the perceived risk of blended finance to landowners. This could reduce the risk of entering into an agreement with an unknown counterparty, and the perception that contract terms could be enforced unfavourably in the event of wildfire or other unexpected event (Online Workshop). It was further suggested that this role could be undertaken by Scottish Government (Highlands Workshop).

An important condition was set by one respondent, who would only find the scenario attractive if it was evident that carbon credits had a minimum price (one of the conditions of potential scenario D, and discussed more in the next section).

Addressing the difficulties faced by smaller landowners or those with common grazing rights could also increase attractiveness. One survey respondent shared, "Not possible for Common grazings shareholders to source that level of funding", indicating a need for additional support or alternative structures for these stakeholders.

5.4 Potential scenario D: Peatland Code with price floor guarantee and public support for maintenance costs

Overview: In this scenario, the upfront costs associated with restoration are covered by private finance instead of being funded by Peatland ACTION. Additionally, a price floor guarantee provides the project with a pre-negotiated minimum carbon price that guarantees a minimum level of profitability. Private finance could be provided by a government-sponsored fund. This financing vehicle is described in more details in the "Policy options" section of the report (see the Scenarios section under Methods Overview and Table 5 for more details on this scenario and its assumptions).

Key scenario components:

- Maintenance payments – fixed annual maintenance payments covering maintenance costs at the same level as potential scenario C, for a period of 10 years.

- Carbon revenue – carbon credits generated through the Peatland Code are sold upon verification, at a price guaranteed by the Government, to support the liability of long-term maintenance costs.

- Private finance – the removal of the Peatland ACTION upfront restoration grant results in an upfront financing gap which can be addressed using private finance.

- Price floor guarantee – a mechanism through which Sottish Government guarantees a minimum price paid for PCUs is introduced. This mechanism is described in more details in the "Policy options" section of the report.

The greater need for private finance (£175,000 to £200,000 initial capital injection needed for the project to cover its early costs) in potential scenario D (compared to current scenario B and potential scenario C) implies higher capital costs. Table 8 shows what IRR an investor could achieve based on a certain carbon price and inflation-linked lease payment made to the landowner.

Under the base case assumptions, with a carbon price of £30 an investor that would pay annual inflation-linked lease payments of £50 per hectare would only achieve an IRR of 6% (versus 15% in current opportunity B). Achieving a similar IRR of 15% with lease payment of £50 would require a starting carbon price of c. £80.

The higher carbon price required in this scenario has implications on the level of the price floor guarantee. Without Peatland ACTION funding for capital costs, a price floor guarantee might need to be set at a level higher than current market prices to enable projects to be economically attractive to investors and landowners. This would expose the Scottish Government to conditional liabilities if carbon market prices are not above the price floor by the time the first PCUs are generated by the project. Given current market prices for peatland carbon (£15 to £25 for PIUs as per published Peatland Code statistics), this suggests that some Peatland ACTION funding might still be required if a price floor guarantee is introduced (similar to the Woodland Carbon Guarantee that does not preclude projects to use the England Woodland Creation Offer). The capital grant of Peatland ACTION funding could then be phased down as the price paid for carbon in the voluntary market increases.

| PCU price (2% real annual growth) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IRR | 10 | 20 | 30 | 40 | 50 | 60 | 70 | 80 | |

| Inflation-linked lease payment per hectare p.a. | 0 | 2% | 6% | 8% | 10% | 12% | 13% | 15% | 16% |

| 50 | <0% | 3% | 6% | 8% | 9% | 11% | 12% | 14% | |

| 100 | <0% | <0% | 3% | 5% | 7% | 9% | 10% | 12% | |

| 150 | <0% | <0% | 0% | 3% | 5% | 7% | 8% | 10% | |

| 200 | <0% | <0% | <0% | 1% | 3% | 5% | 6% | 8% | |

IRR <5%

5% <= IRR < 15%

15% <= IRR < 25%

IRR >= 25%

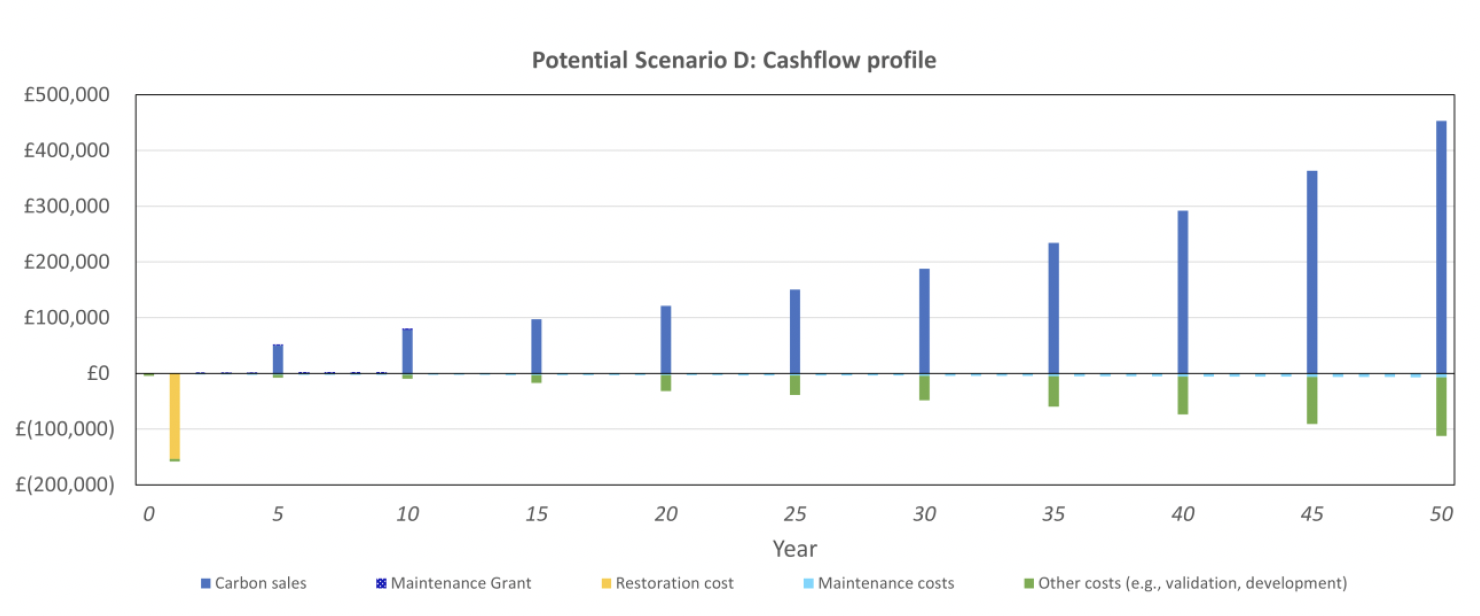

Net operating cashflow (6% discount rate): £83,000 (Figure 7).

Key considerations for the project owner: A guaranteed carbon price combined with grant funding to support the first 10 years of maintenance costs significantly reduces the level of project risk. Given the upfront financing need created by the absence of Peatland ACTION grant, some of the project risk could also be shared with an investor. It is worth noting that an investor would require a financial return, which would require the landowner to share the project value with the investor.

Key considerations for Scottish Government: Under this scenario, maintenance grants are fixed (NPV = minus £14,000, 6% discount rate applied), however, the introduction of the PFG mechanism creates a conditional liability to be managed by the Scottish Government. Table 9 presents an illustration of how costs to Scottish Government would vary, depending on the market price of carbon and the price set by the PFG. In summary:

- Where carbon market price = PFG, it may be easier for the project to sell PCUs to Scottish Government, hence incurring a cost to Scottish Government under this scenario.

- The Government in England established a PFG for woodland creation schemes – the Woodland Carbon Guarantee (WCG) – which provides a guaranteed price for verified Woodland Carbon Units up to 2055/56. Under the WCG, the price of the price floor is agreed through an auction. The first of these auctions took place in January 2020. Given it takes >5 years to generate and verify carbon credits from woodland creation projects, there is currently no evidence as to the extent to which projects have exercised the guarantee.

- By limiting the use of the WCG to carbon credits generated up to 2055/26, the Government in England is able to cap the costs incurred by the projects exercising the WCG. A similar cap could be applied to the PFG, limiting the use of the PFG to PCUs verified before 2050.

| Scenario | Impact on cost to Scottish Government | |

|---|---|---|

| Where market price > PFG | All PCUs sold on the market. No costs incurred by Scottish Government. Depending on Scottish Government's accounting practices for contingent liabilities, capital may need to be set aside for the duration of the contract. | |

| Where market price < PFG | a. PCUs purchased by PFG are sold on the market | Scottish Government is able to resell purchased PCUs on the market, reducing the overall cost to Scottish Government. Cost to Scottish Government would equal the PFG level minus price of resale (e.g. if the PFG was set at £30, and the market price of a PCU was £20, the cost to Scottish Government would be £10/PCU) |

| b. PCUs purchase by PFG are retired by Scottish Government | Full costs incurred by Scottish Government (e.g. if the PFG was set at £30, and the market price of a PCU was £20, the cost to Scottish Government would be £30/PCU). Compared to a., this option maximises net environmental gain as the PCUs are not used to offset emissions generated elsewhere. | |

Table 10 provides a depiction of the NPV associated with the cost of providing a price floor guarantee for Scottish Government across various market prices for PCUs and corresponding price floors. In instances where the market price for PCUs exceeds the floor price, the cost incurred by Scottish Government is zero. Conversely, if the market price is below the agreed-upon floor, the PFG is activated, compelling the government to acquire PCUs from the project at the pre-determined floor price. The sensitivity analysis assumes a 50-year project lifespan with the price floor safeguarding all credits issued throughout this period. However, in practical scenarios, the price floor might only secure PCUs verified during the initial 10, 20, or 30 years of the project, which would reduce the cost to Scottish Government.

| Starting PCU market price (2% real annual growth) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| £10 | £20 | £30 | £40 | £50 | £60 | £70 | £80 | ||

| Starting price floor guarantee (inflation linked) | £20 | 113,953 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| £30 | 202,555 | 118,599 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| £40 | 270,073 | 227,906 | 87,769 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| £50 | 337,591 | 322,875 | 231,731 | 109,711 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| £60 | 405,109 | 405,109 | 341,859 | 237,197 | 64,008 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

The risk of project failure is lower than in the previous three scenarios, because minimum carbon revenues are guaranteed and the Peatland Code agreement contains a contractual obligation to maintain. As a result, long-term maintenance obligations are funded and the project is less at risk of degrading over time after the restoration is completed. Additionally, Scottish Government is contributing less grant money and part of the project failure risk is transferred to a private investor, if the project owner decides to raise external private finance. However, from a financial liability perspective, Scottish Government is exposed to peatland carbon prices if these remain below the price floor.

Clarity of scenario: The survey asked participants to assess the clarity of the financial scenario, with an average (mean) clarity score of 70.22/100, denoting a moderate-to-high level of understanding among respondents. This inference is further supported by the median value of 74. There was however a broad spectrum of perceptions, with the standard deviation (which measures the dispersion of the values from the mean) coming in at 23.6 (out of 100), indicating substantial variability in responses.

Alignment with personal values: Regarding the statement, 'this scenario aligns with my personal values', 41% of the respondents agreed with this statement (specifically, 6% strongly agreed, 22% agreed, and 13% somewhat agreed), with 22% disagreeing (0% somewhat disagreeing, 9% disagreeing and 13% strongly disagreeing) signalling that this scenario was one of the stronger fits with people's values. However, there were also a significant proportion of neutral respondents (38%).

Likelihood of adoption: When considering whether they would sign up to this kind of scenario, 53% of respondents agreed (3% strongly agree, 20% agree, 30% somewhat agree), while 27% disagreed (17% strongly disagree, 10% disagree, 0% somewhat disagree). 20% of the respondents chose Neutral. This data reflects a majority interest in the proposed scenario, yet a significant portion of the respondents remain hesitant or strongly opposed. When considering landowners in Scotland more widely, results were largely the same, with a slight increase in neutral responses and lower disagreement (53% agreed, 20% disagreed, 28% remained neutral) – indicating respondents were hesitant to project their negative sentiments on to other landowners.

Attractiveness: When considering attractiveness of the scenario, the mean score was 62.06/100, indicating a generally moderate level of attractiveness for the scenario. The median score was 70 out of 100, suggesting that the central point of responses leaned more towards the scenario being attractive.

The remainder of this section provides an analysis of qualitative feedback on the scenario, and how it might be enhanced, based on data from surveys, interviews and workshops.

Fit with financial needs: 37% of respondents agreed (11% strongly agree, 19% agree, 7% somewhat agree) that the scenario fitted their financial needs. Meanwhile, 30% disagreed (0% strongly disagree, 19% disagree, 11% somewhat disagree) with this statement. A considerable proportion of respondents, 33%, remained neutral. These findings indicate a divided sentiment amongst respondents regarding the financial suitability of this scenario, with a large group neither agreeing nor disagreeing.

The price floor was perceived as an attractive benefit

Participants considered this price floor mechanism would reduce downside risk but also allowed potential to benefit from upside, and "would allow for greater transparency and a minimum price certainty" (Survey Response). The price floor was also described as "guaranteed funding" (Participant 19) and that it provided an "insurance policy - you can work it out and worst-case scenario you are going to get that for your carbon" (Participant 34). The participants thought it would provide stabilisation to the market in the long term.

The price floor was deemed to be most attractive to larger landowners and outside investment. One agent/advisor described potential Scenario D as "pro-business" (Participant 32) and attractive to investment funds looking to enter the market, enabling "the financial world to deploy cash at the scale necessary" (Participant 9). Parallels were drawn between the price floor and the feed-in tariff scheme to support the development of renewable energy schemes. Participants suggested that the industry is already familiar with this feed-in tariff model, and suggested that if revenues are known (or revenue uncertainty reduced) then landowners are better able to raise finance and reduce the cost of borrowing:

"[Valuing carbon] with a degree of confidence is one of the major risks and certainly for mobilising capital and the cost of that capital, the government underpinning [the price of carbon] would be an attractive option … and could actually create an environment where a lot more of these projects are happening." (Participant 36)

One participant suggested that a price floor may also be attractive to smaller landowners and help to reduce the intangibility of carbon, especially for farmers who are currently hesitant or reluctant to enter these schemes:

"Farmers are used to an element of risk. You spend £30 producing a lamb every year and you know roughly what you are going to get. But if you started [carbon credits], somebody going into this blind, it would be difficult for them - it is not a lamb." (Participant 35)

Some participants speculated on the upside potential of the scenario, rather than merely seeing the price floor as a safety net, which is easier to do when you are always guaranteed a certain price:

"The closer you get to 2045, companies are going to get desperate and you would imagine it is going to go pretty crazy … So, we are expecting the market to rise like that so in [potential scenario D] … you can benefit from the higher [price]." (Participant 27)

Practicalities of the price floor

A reliable price floor was seen to be key to the success of this model. However, one participant questioned whether sufficient data was available for the government to determine the appropriate price floor. The price floor became a focus for discussion during the South of Scotland Workshop, where it was suggested that a price floor could be set through reverse auction, as had been employed during the implementation of the Woodland Carbon Code Guarantee. Concerns were also raised around the duration of the price floor; whether the Scottish Government could credibly commit to maintain such a facility through policy and political changes, and how it would be funded (South of Scotland Workshop).

There was also concern about the long-term viability of the guaranteed price floor for carbon, with questions raised such as "is this price guaranteed for 100 years?" (Survey Response) which may indicate that the respondent is unsure whether the government will provide guarantees over such a long period of time.

NGO land managers highlighted the important co-benefits of peatland carbon investments and questioned whether a single price floor would provide sufficient incentive to develop schemes that provided environmental and social net benefits:

"I think a floor price might accidently make all units seem the same." (Participant 4)

Issues for smaller landowners

There was a perception amongst smaller landowners that it would require a lot of work for little gain, with sentiments such as "[I'm] not sure the cost makes it worthwhile" (Survey Response) being commonplace. This sentiment was expressed across different type of landowners/managers, including an NGO:

"It sounds like a lot of work. As a land manager, I don't have the capacity - I manage 14 [sites]. … I like the option of Peatland ACTION doing all the work (current scenario A) because it means I can carry on with my job." (Participant 24)

A crofting common grazing committee member suggested the scenario would be "a lot of stress in the work [with] nothing to show at the end of it" (Participant 27). Similarly, a farmer suggested they would be "made to do all the hard work [with] no upside" (Participant 28).

As before, some participants considered that they lacked sufficient knowledge or experience to be comfortable engaging in carbon finance, with the suggestion that the private finance company would have to take the lead on this, which creates a power imbalance and the owners having to share credits with the investor, as well as pay transaction costs:

"You are looking for a very sophisticated investor who understands finance in great detail and is prepared to take risk. That is not traditionally an upland farmer … so I think you have got a total mismatch." (Participant 28)

"[Landowners] would be forced to bring in partners which is going to increase administration costs and essentially have more companies taking part of the pie. It will be good for middlemen in terms of contracts and lawyers [etc]." (Participant 32)

Reputations of those involved in financing are crucial to gain trust

Similarly to the previous scenario, several respondents voiced concern about the potential pitfalls of private finance, particularly around the ethical credentials of potential investors. One person stated, "we would only want to sign up for this if we could guarantee the source of private finance had exceptional green credentials, themselves" (Survey Response).

This scenario introduces a degree of governmental support (compared to potential mechanism A, which was strictly private finance), with grants and the price floor guarantee being provided as support. There were mixed opinions amongst participants over this blended option. As expressed by one survey response, "It's better than the previous scenario as government is involved - less risk". Further, another survey respondent underscored the potential benefit of private-public partnerships: "private - public partnerships can be an added good." This indicates recognition of the value of shared investment and risk in this scenario.

However, another respondent had reservations about government involvement, stating, "I personally don't feel Government demand-side involvement is the way to go - there is huge demand and interest in controlling carbon units" (Survey Response). This viewpoint may suggest that some individuals value market-driven approaches. Yet, another individual found the prospect of public funding supporting private investors unsettling, saying, "Restores peatland, but it feels odd that public funding (for maintenance) is being used to support private investors" (Survey Response). This sentiment suggests the belief that public funds should not be used to support private profit and further emphasises the divergence of opinions on this subject.

Sale of credits a contended issue

The issue of (forced) selling of carbon credits was again raised in this scenario. The emphasis on sale of credits (to help cover initial costs and maintenance) was not attractive to farmers and crofters, who wished to retain credits against future requirements to inset carbon within their businesses:

"[Farmers] are wanting to generate their own carbon credits to inset … they don't want an investor or a finance vehicle to get involved" (Participant 7)

Negative aspects centred on the lack of grant funding to cover capital cost of restoration and the emphasis this would place upon selling carbon credits early or bringing in private finance. Participants perceived that the requirement to finance capital cost could create cash flow problems and prove a barrier to those who are not cash-rich:

"We are absolutely paranoid about making sure we go down the right route with that. If there is no upfront funding available, then that would still be quite a massive barrier." (Participant 30)

More generally, participants perceived that forward selling carbon left landowners open to additional financial risks:

"The danger is if you sell your credits and then you have to re-buy some because of some disaster and the value has gone up, the carbon market has made you poorer rather than richer." (Participant 15)

Opposingly, however, some people wanted to forward sell their carbon credits, and that this scenario could in fact "make the forward selling of carbon units quick and easy" (Survey Response) as there will be an intermediary ready to buy these from the landowner.

Risks involved in the scenario

In response to the statement, 'This scenario is too risky for me', 21% of respondents agreed (9% strongly agree, 9% agree, 3% somewhat agree). Conversely, 45% of respondents disagreed (6% strongly disagree, 24% disagree, 15% somewhat disagree) which was one of the highest scores across all scenarios. Meanwhile, 33%, chose neutral, indicating uncertainty or a need for more information to form a solid judgement on the perceived risk level. Responses were similar when asked to access if the scenario was too risky for landowners in general, with 24% agreeing, 41% disagreeing and 35% remaining neutral.

Several participants highlighted that the price floor and guaranteed buyer could help to reduce the risk of engaging in peatland restoration as an investment and give them "some sense of what the revenues will be" (Participant 16). Contrastingly, another participant did not consider that a price floor on its own would be strongly effective in reducing risk because, while it would provide more assurance on revenues, it would not reduce wider unknowns of peatland restoration or the Peatland Code:

"[The price floor] doesn't provide enough confidence and risk and mitigation to get somebody to go from not looking at a peatland project to being looking at a peatland project. I think as an initial tool within a combination, it would be powerful, and I think as a stand-alone isolated thing it is neutral" (Participant 5)

One participant considered that cutting out Peatland ACTION would increase risk because part of their function is to assess the risk and viability of proposed restoration designs:

"If you don't have that (Peatland ACTION advice) in place, then you could be looking at quite poor, quite rushed designs that haven't been properly assessed by people with technical expertise. … I would be very, very cautious about not having any grant with any rigorous assessment process with it." (Participant 6)

Participants also highlighted a number of more generalised risks highlighted in the analysis of potential scenario A, earlier. Key amongst these were the long- term nature of the contract, alongside a potential lack of knowledge/experience among market participants to sufficiently evaluate the risks. One participant also perceived that there could be an early-mover disadvantage, if more attractive options became available in future "precluding yourself from something else further down the line" (Participant 4).

Making the finance scenario more appealing

In terms of financial certainty, respondents highlight the need for increased clarity around the process and conditions of private financing. One participant said they would find the scenario more attractive with an "understanding of the private finance facility and condition of its use, including any payback" (Survey Participant).

Concerns were raised that the current scenario might push landowners towards less risky, and potentially less beneficial, restoration works. One respondent noted that "I don't find this attractive at this stage as it would push landowners into only doing the least risky restoration works that fit the quite limited Peatland Code eligibility/economics" (Survey Response).

Contact

Email: peter.phillips@gov.scot

There is a problem

Thanks for your feedback