Overcoming barriers to the engagement of supply-side actors in Scotland's peatland natural capital markets - Final Report

Research with landowners and managers in Scotland to better understand their motivations and preferences to help inform the design of policy and finance mechanisms for high-integrity peatland natural capital markets.

7 Conclusions and proposed policy options

Based on feedback from surveys, interviews and workshops, it is possible to propose two mechanisms that increase supply-side engagement and provide inclusive access to funding for peatland restoration, whilst responsibly scaling peatland carbon markets:

1. The retention of current Peatland ACTION funding, with or without accreditation to the Peatland Code. It is important to consider retaining this route for those who do not wish to engage with private finance, given the strength of opposition to market engagement expressed by many participants in this research, so they still have access to restoration funding.

2. The introduction of a new, blended finance option for Peatland Code projects within Peatland ACTION, repurposing public funding to create a price floor guarantee, funding for maintenance costs and ongoing advice based on site assessments from Peatland ACTION officers.

A number of adaptations were proposed by respondents to the design of the new blended finance option in Peatland ACTION, which have been integrated into the design of the proposed mechanism in the next section. The introduction of a new mechanism is not mutually exclusive with the retention of the current Peatland ACTION funding model, with or without the Peatland Code. The two mechanisms could coexist, which would accommodate for the preferences of the market participants who engaged with this research.

7.1 The proposed blended finance mechanism

In order to build an efficient and coherent funding and financing ecosystem for peatland carbon projects, it is proposed that existing public funding (Peatland ACTION) is repurposed and/or new public funding is used to:

1. Establish a price floor guarantee for Peatland Carbon Units (PCUs);

2. Provide annual maintenance grants to support the medium to long-term maintenance costs of peatland restoration projects; and

3. Provide subordinated capital to a proposed Scotland Carbon Fund, in the form of a first-loss guarantee.

These aligned mechanisms would help set strong governance standards for the peatland carbon market, build market integrity and support the scale-up of private investment in peatland restoration in Scotland. These measures build upon those first proposed in the April 2023 report for Scottish Government, 'Mobilising private investment in natural capital.'

7.1.1 Price floor guarantee

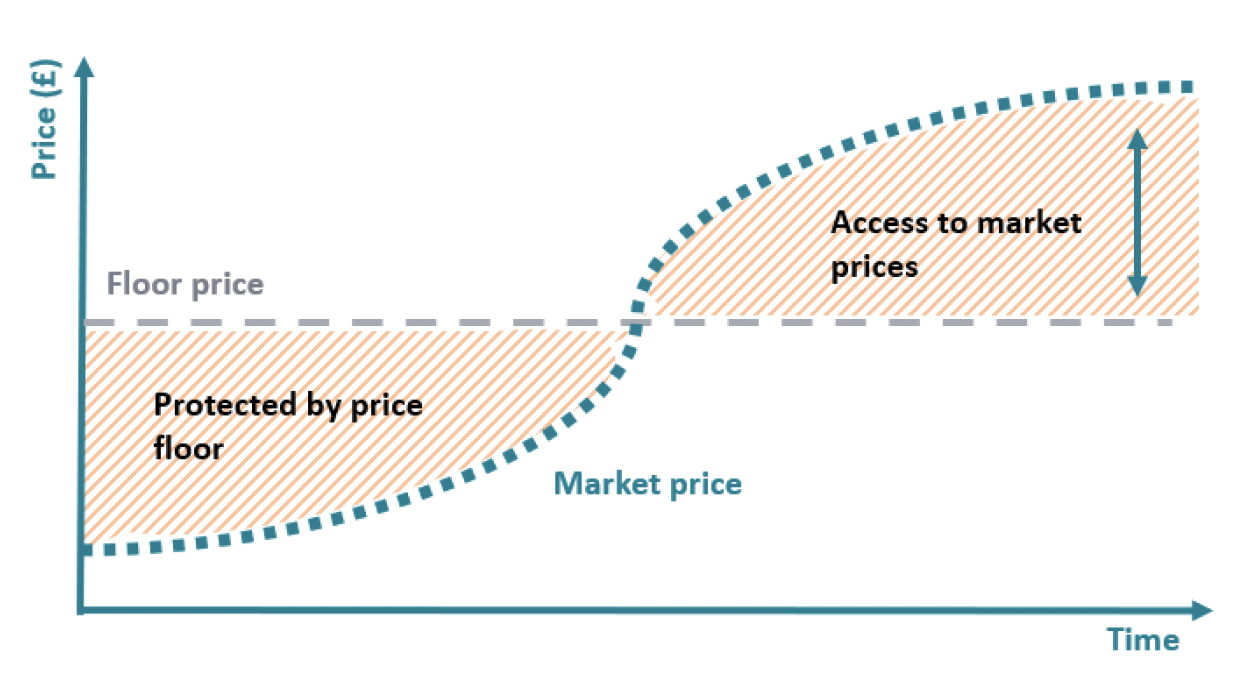

A price flood guarantee (PFG) is a risk reduction or risk transfer mechanism. The mechanism offers confidence in project revenues over a fixed period, which significantly reduces the downside risk profile for both investors and project developers (see Box 1 for examples of PFGs in the UK). As evidenced in Figure 8, if market price is below the floor price, the project can sell verified carbon units at the level of the price floor guarantee. If market price is above the floor price, the project can capture the upside by accessing market prices. The design of the mechanism could require sales to the market where the market price is above the price floor, reducing risks to public funds.

Box 3: Examples of existing floor price mechanisms

UK Feed-in Tariff (FIT)

The Feed in Tariff is a UK government programme introduced in 2010 designed to promote uptake and financing of renewable energy generation technologies through providing price certainty for energy generated alongside subsidy payments.

Woodland Carbon Guarantee

The Woodland Carbon Guarantee was a £50 million government scheme designed to stimulate woodland creation in England through providing a guaranteed carbon price for verified Woodland Carbon Units issued under the Woodland Carbon Code.

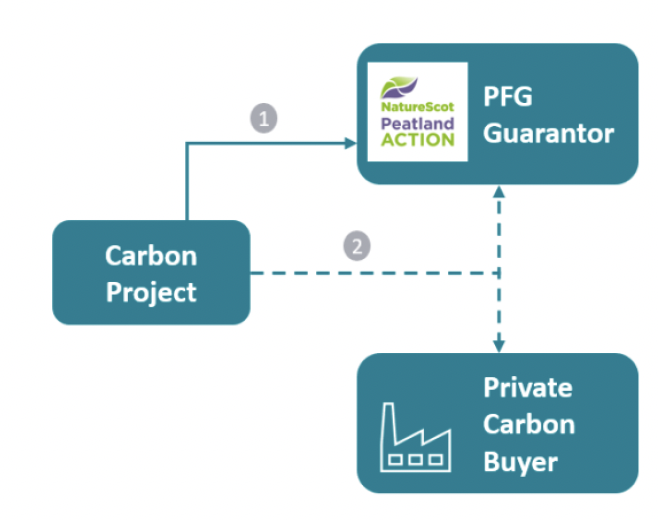

The proposed structure of the PFG is outlined in Figure 9:

1. The project submits a bid to secure a price floor agreement for the future sale of their PCUs to the PFG Guarantor (e.g., Scottish Government). Typically, a reverse auction would be organised and projects would aim to bid above their cost base, in order to ensure profitability or at least break-even; and

2. Income is generated by the project from the sale of PCUs and/or PIUs to corporates or brokers. If market prices fall below the price floor, PCUs can be sold to the guarantor at the pre-agreed price threshold. If market prices are higher than the price floor, PCUs would typically be sold on the market, not triggering the guarantee (this could be made a requirement of the scheme).

7.2.2 Implications of a price floor guarantee for the Guarantor

The guarantee reduces downside risk to participants (i.e., the risk of low carbon prices negatively impacting the financial viability of a project). Where designed effectively, and if carbon prices are increasing over the period during which the guarantee operates, this is achieved with minimal government pay out to participants.

If the guarantee is exercised, the guarantor can choose to resell the credits in the market at a lower price (incurring a loss per credit that is the difference between the price floor and the market price) or retire the credits (incurring a loss per credit equivalent to the price floor). Additionally, should carbon prices remain low, Scottish Government could decide not to launch new auction rounds. More details regarding the modelling of the costs of a price floor guarantee for the Scottish Government is available in the previous chapter.

7.2.3 Maintenance grants

A proportion of exiting Peatland ACTION funding could be repurposed to an annualised maintenance grant to support the medium to long-term maintenance costs of peatland restoration projects. Further work is required to determine adequate grant rates that can cover project maintenance costs and be flexible enough to adapt to potential variability in projects' maintenance costs (e.g. peat baseline condition, project remoteness, etc).

These maintenance grants could be provided for the first 5-20 years of a project on a conditional or outcomes-linked basis. Linking maintenance grants to the delivery of specified outcomes reduces the risk to Scottish Government of non-delivery, especially in the case of landowner / manager negligence. However this outcomes-based approach should be weighed up against additional complexity and costs to monitor and verify outcomes.

7.2.4 Scotland Carbon Fund

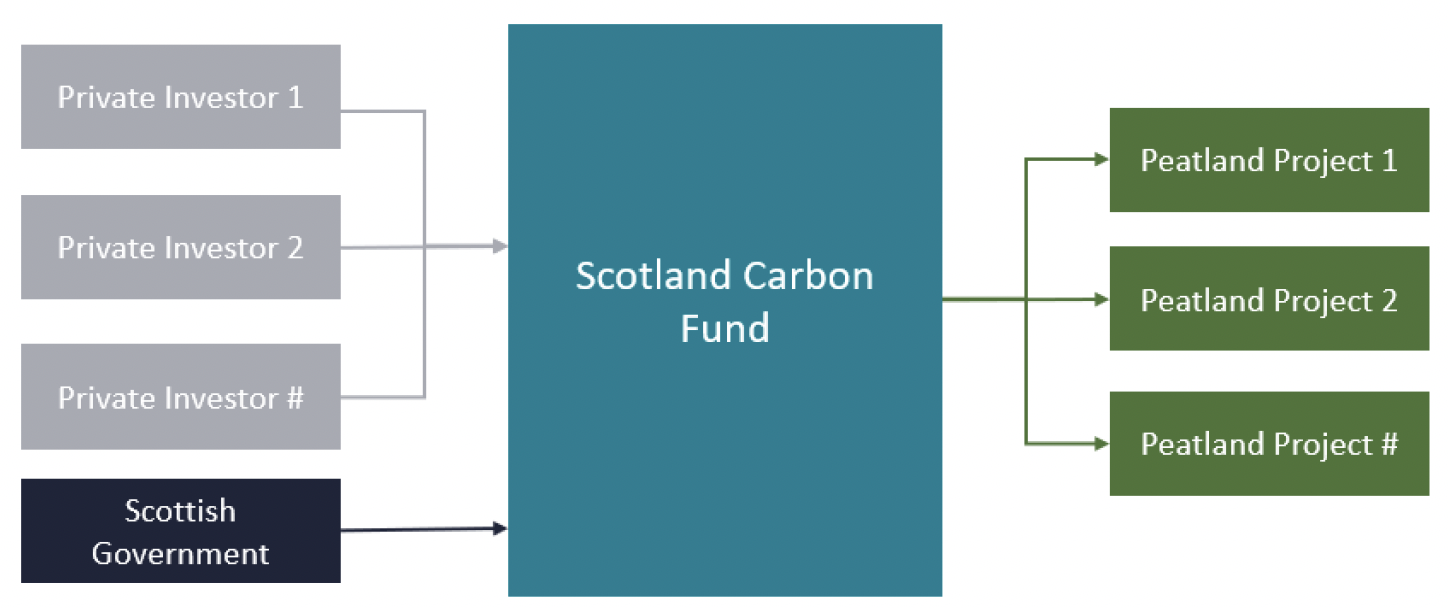

The restructuring of the Peatland ACTION grant for capital works would result in an upfront financing gap which could be addressed through the use of private finance. A Scotland Carbon Fund (SCF) could facilitate the flow of private capital to peatland restoration projects to address this upfront financing gap.

The purpose of a Scotland Carbon Fund would be to act as an investment vehicle to aggregate private capital to invest in high-quality peatland restoration projects in exchange for financial returns generated from the sale of PCUs, as illustrated in Figure 10.

The SCF, structured as a project finance vehicle, would enable the scaling of peatland restoration in Scotland by leveraging public capital provided by the Scottish Government to crowd in private investors.

A potential financial contribution from the Scottish Government to the SCF was perceived as a crucial stamp of approval and display of commitment to the peatland carbon market by the investors consulted as part of the Mobilising Private Investment in Natural Capital project. The report recommended that the contribution be structured as first-loss capital. The introduction of first-loss capital would constitute a compelling investment proposition to investors, reducing risk whilst also providing confidence in the market.

7.3 Enabling factors

Taken together the new blended finance mechanism, in combination with a publicly funded mechanism similar to the current system, have the potential to address many of the barriers to supply-side engagement in peatland carbon markets. However, to be successful the research suggests that a number of additional mechanisms may be necessary to achieve widespread adoption of the new mechanism:

- Many landowners were concerned about the complexity of the new mechanisms and this, combined with the perceived administrative burden, could limit adoption. To circumvent this, a number of design features and adaptations could be considered:

- Ensuring the relative advantages and disadvantages of new mechanisms are clear and easy to understand, by providing comparisons with previous and alternative options (e.g., the publicly funded route that is retained via Peatland ACTION, as proposed above);

- Providing illustrations of potential advantages and disadvantages of adopting the new mechanism for different types of landholding (see communication options below);

- Ensuring the application process for any new mechanism is aligned with the existing schemes' application processes, actions, conditions and requirements. This is particularly important for smaller landowners and crofters with limited capacity for engagement and/or limited technical understanding of the various schemes;

- Working with already trusted advisors and intermediaries within the sector to support landowners' applications, while keeping the decision-making and application process as straightforward as possible. To do this, it would be necessary to build capacity via training and support for Peatland ACTION officers, advisors, land agents and other intermediaries to help landowners develop projects that are eligible for the new blended finance mechanism; and

- Reducing friction for landowners and their advisors by creating standard contract templates that could facilitate benefit sharing with tenants and crofters and their landlords and adequately cover the new blended finance mechanism.[9]

- Concerns were raised about the implications the new mechanism could have with regards to affecting eligibility for future agri-environment schemes and the implications for Inheritance Tax (IHT) and Agricultural Property Relief on land taken out of production. Therefore:

- It may be necessary to work with Treasury to introduce a new type of "conservation property relief" or to reclassify "agriculture" to also include peatland restored under high-integrity market schemes; and

- Clarity is also required on whether crofters (who have peat cutting rights) or landlords (who have mineral rights) have the rights to peatland carbon in Scotland.

- Many of the greatest concerns around engaging with peatland carbon markets focused on the potential for greenwashing, where credits are purchased by companies that have not done everything possible to reduce emissions at source level (e.g., fossil fuel, industrial or, aviation companies etc). Further consideration should be given to operationalising the Voluntary Carbon Market Initiative's (VCMI) Claims Code of Practice as this would address concerns expressed over the potential for greenwashing in carbon markets. This could be done, for example:

- As part of the (currently interim) Principles for Responsible Investment in Natural Capital on a voluntary basis, signposting landowners to intermediaries or platforms that will vet buyers to avoid greenwashing;

- Via the British Standards Institute (BSI) Nature Investment Standards Programme, which is considering the development of a BSI standard to contextualise and implement the VCMI Claims Code in the UK, versus the integration of buyer checks in line with VCMI across the standards they are developing (which would require the Peatland Code to conduct these checks on all buyers); and / or

- Via collaboration with UK government colleagues to adapt the Companies Act 2006 (Strategic Report and Directors' Report) Regulations 2013, to make an amendment requiring reporting to align with the VCMI's Claims Code. This would be similar to the Companies (Strategic Report) (Climate-related Financial Disclosure) Regulations 2021, which require disclosures to align with guidelines from the Taskforce on Climate Related Disclosures.

- The research highlighted a long-standing and common complaint with the current approach of natural capital markets from those that have retained their land in good condition only to see those who have degraded their land benefiting from carbon markets. Further strategic thinking is required to explore the opportunities for good stewardship maintenance payments. This could, for example include a new agri-environment scheme option for maintaining peatlands in good condition. Condition could be defined in relation to 'comparable' sites (e.g., defined by soil sampling from the National Test Programme). This would help increase the permanence of Peatland Code projects, where completed projects then qualify for ongoing payments for maintaining sites in good condition (not however that such payments might fall into "Amber Box" of the World Trade Organization).

7.4 Integrating tax

In addition to the enabling factors above, a tax on degraded peatlands may also be considered acting as a disincentive on engagement:

- Opinions on a tax were mixed and the introduction of any new tax would be controversial. If it were introduced in combination with more attractive terms for funding restoration, it may be possible to limit the negative impact of the tax as landowners that restore their peatland would not only avoid the tax but they would profit from selling units via the Peatland Carbon Code.

- Within the research environmental NGOs and those whose peat was not heavily degraded were most likely to be in favour of tax instruments linked to emissions from land. These owners of better quality peatland argued that such a tax might motivate more landowners to engage with restoration, especially those currently waiting in expectation of carbon market prices increasing or other incentives to emerge (a major bottleneck to restoration). The new blended finance mechanisms proposed in this report may act to sufficiently de-risk and reward landowners that decide to act, but it is unlikely this alone will materially increase adoption whereas the combination of a degraded peatland tax might. However, it is not clear what the unintended consequences or implications of such a tax might be such as the effect on land prices. If tax was levied on a landowner with poor quality peatland, this might lead to the land being sold. Hypothetically a buyer could be offshore registered which would limit the tax receipt from the degraded peat. Further research and consideration is required to the potential implications on land ownership of the introduction of a degraded peat tax.

- Many participants also noted that taxation was not the correct approach based on the elements of fairness, equal opportunity and the fact that there has been contradictions in the nature of successive government policies (e.g. see Reed et al., 2020). One example cited was peatland drainage under the 1970s Common Agricultural Policy. The respondent's main argument against taxation was fairness as degradation may be due to causes beyond the current owner's control (e.g., deer from a neighbour, previous government schemes or management by previous owners) and due to site accessibility / terrain it may not be possible to restore the land. It may be necessary to allow exemptions to the tax on the basis of accessibility or unique circumstances to ensure any new tax does not unfairly penalize a landowner. Further research and consideration is required to assess the implication that exemptions might create (financial burden from the requirement for more officers, delays to projects etc).

- Issues would also need to be resolved around how such a tax would affect crofters, who may not find it cost effective to restore small parcels of land and those on common grazings, where it may be difficult to identify who is liable for the tax.

- To operationalize such a tax, clear criteria would need to be established to identify degraded sites and one option would be to adopt the Peatland Code condition categories which are linked to emissions factors. This may also provide the groundwork for future applications for projects under the Code.

- If a degraded peat tax was introduced, funds raised via tax receipts could be used to pay for projects that are restoring peatland, protecting the public purse. This would help meet the increased demand for restoration funding likely to be stimulated by the tax but could only have a limited life expectancy where receipts are less than mechanism payments.

7.5 Communicating the new mechanism

A communication strategy may need to be developed to support the launch of a new blended finance mechanism (and any accompanying tax). If done well, such a strategy has the potential to reduce perceptions of risk, given that a number of the main perceived risks were based on a misunderstanding of the mechanism:

- Messaging should be tailored to the different values for nature held by different types of supply-side actors. For example, messages about new blended finance mechanisms could be framed in terms of self-regarding (e.g. financial, risk, etc.), broader personal (e.g. place identity), collective values (e.g. fairness, environmental protection) and social benefits (e.g. collaboration opportunities and benefits to local communities) as much as the benefits for climate change and biodiversity.

- Messages may also be framed in ways that are consistent with the identity of land managers (e.g. land stewards or adaptive innovators diversifying their businesses to meet public demand and custodians protecting existing benefits), rather than reframing them in roles they do not identify with (e.g. park rangers or carbon farmers, delivering an agenda for a Government they may not trust).

- Where possible, these messages should be delivered via trusted intermediaries or peer-to-peer networks, including other supply-side actors or their advisors (see the point above about training for advisors).

- Respondents found it difficult to evaluate the likely benefits or drawbacks of adopting the proposed mechanism in the context of their own landholding. For this reason, it may be beneficial to communicate outcome scenarios for different types of farm and estate businesses, that are operating at different scales and have peatlands exhibiting different states of degradation. This may be based on the financial modelling conducted in this project, which led to the illustrations summarized below or be based on a more detailed financial analysis to be undertaken. This could include different farming enterprises and production systems, estate activities, and how to integrate peatland restoration into each, i.e., what stocking densities, deer densities, or game animal practices may be permissible post-restoration.

Contact

Email: peter.phillips@gov.scot

There is a problem

Thanks for your feedback