Pandemic Ready: Safeguarding Our Future Through Preparedness

Final report of the Standing Committee on Pandemic Preparedness. This responds to the commission by the former First Minister, Nicola Sturgeon, for the Standing Committee on Pandemic Preparedness to provide advice to the Scottish Government on preparedness for future pandemics.

Introduction

The people of Scotland have experienced one of the most significant pandemics to affect the world for a century. We have seen the impact it has had on our families, friends and communities as well as the wider scarring on education, society and the economy.

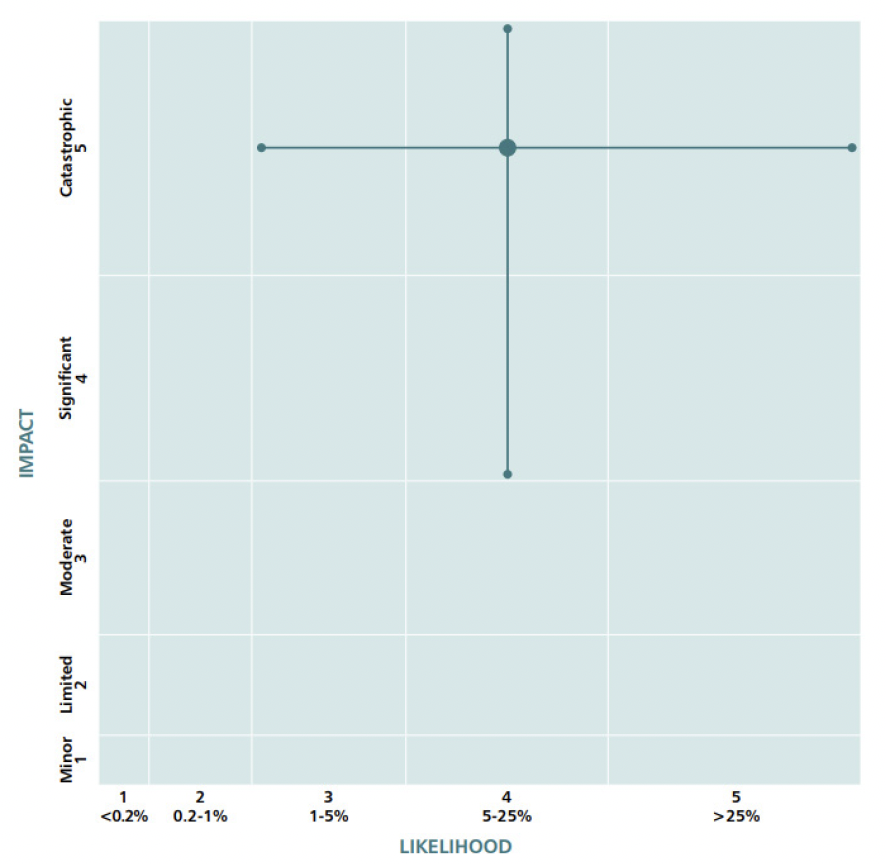

We are acutely aware of the cost of pandemics, and we know that COVID-19 is likely not the only pandemic we will have to face. Globalisation, increases in international travel, climate and ecological changes, and urbanisation have substantially increased the risk of infectious disease outbreaks. Accordingly, pandemics and infectious disease outbreaks are classified in the highest risk category within the UK 2023 National Risk Register. The scoring of the pandemic risk from the UK National Risk Register is included in Figure 1 below.

For both pandemics and infectious disease outbreaks, the risks are assessed as having a 5-25% likelihood of their reasonable worst-case scenario occurring in the next five years. It is therefore essential that we plan ahead to mitigate the risks of future pandemics. That is why the SG established the Standing Committee on Pandemic Preparedness (‘the Committee’),[3] chaired by Professor Andrew Morris, to bring together public health scientists, clinicians and technical experts to advise the SG on the future risks from pandemics and to ensure we are as prepared as it is possible to be for these.

Scope

The Committee’s terms of reference[4] specify that its role is: “providing expert advice on the risk from and preparedness for future pandemics […] but not to economic or wider aspects of preparedness not connected to public health”. The recommendations included in the Interim and Final Report therefore focus on areas within the scope of those terms of reference.

The Committee does, however, wish to underline the fundamental importance of a resilient National Health Service (NHS), health and social care system, and public health service for Scotland’s ability to respond to and mitigate the impact of future pandemics. The challenges facing the NHS and social care system in Scotland are stark and, coupled with existing vulnerabilities and population health challenges, they present a major risk to Scotland’s ability to respond effectively to future pandemics. These challenges are not addressed in this report as they are outwith the terms of reference of the Committee, but it is crucial they are addressed by the SG, PHS, NHS Scotland and its Boards, Local Authorities, and partners.

The Committee is aware of work underway to address these challenges, including the upcoming Population Health Framework being developed jointly by the SG and COSLA alongside wider NHS reform[5] and is supportive of these endeavours. Nevertheless, the challenges remain stark.

The Committee’s Interim Report

The Committee’s Interim Report,[6],[7] published in August 2022, acknowledged the work being done in Scotland by institutions such as the RSE,[8] the SSAC[9] and others to learn from the experience of COVID-19 and make recommendations for the future. It also noted seminal contributions from international bodies including the WHO,[10] and the G7 100 Days Mission to respond to future pandemic threats.[11] The Interim Report concluded that “lessons should be drawn from the experience of COVID-19 in order to shape future pandemic preparedness, whilst recognising the next pandemic may differ substantially from COVID-19.”[12] That learning process will continue, with both Scottish[13] and UK[14] COVID-19 Inquiries underway. The Committee notes the recent publication of the UK COVID-19 Inquiry’s report on Module 1[15] where a number of the recommendations raise points also made in this report.

This report builds on the recommendations made in the Interim Report, which focused on areas where work should immediately begin to improve future pandemic preparedness in Scotland. It makes recommendations on the use of behavioural science to support pandemic preparedness and on further work to advance the Interim Report’s recommendations on:

- collaboration: to develop proposals for the creation of a Centre of Pandemic Preparedness in Scotland;

- data: to build on Scotland’s existing data and analytics strengths to advance their development as core infrastructure for future pandemics;

- advice: to develop linkages to Scottish, UK, and international scientific advisory structures, networks, and agencies and strengthen information flows from these in order to inform Scottish preparedness and response; and

- innovation: to support continued innovation in life sciences and public health for the development of diagnostics, vaccines, and therapeutics to provide the capability to respond to novel threats.

Since the publication of the Interim Report, the Committee has also been involved in commenting on the methodology and articulation of the infectious disease and pandemic risks as part of the UK and Scottish Risk Assessment processes. The Committee was pleased to note that the risk of pandemics has been expanded to a greater range of pathogenic threats than those previously included in these risk assessments. Experts consider a respiratory pathogen to be the most likely cause of a future pandemic affecting the UK and the Committee is aware that the SG continues to plan and prepare for these, alongside a range of pandemic and emerging infectious disease scenarios across possible transmission routes. This approach covers known and unknown pathogens, including ‘Disease X’, as referred to by the WHO.

Effective pandemic preparedness requires strengths in research, innovation and delivery. It requires a deep understanding of the likelihood, nature, and diversity of potential pandemic threats, as well as the range and effectiveness of available countermeasures. Both threats and countermeasures are constantly evolving, necessitating preparedness plans that are continuously updated and remain agile. The next pandemic could arise from other novel coronaviruses, paramyxoviruses, influenza viruses or filoviruses which may prove to be more transmissible and potentially more lethal than COVID-19. We must avoid the pitfall of preparing only for the last pandemic we faced.

The COVID-19 pandemic underscored the necessity of a cross-sectoral approach to pandemic preparedness. Public health, health and social care services, scientists and policymakers must collaborate within a unified and cooperative framework. This collaboration must also encompass the behavioural and social sciences to ensure that scientific advice, policy implementation, and public engagement are both effective and impactful.

Our experience during the COVID-19 pandemic demonstrated that Scotland’s combined strengths – through PHS, the SG and its CSO and CSA office, the NHS, and Scottish research institutions and universities – can be mobilised effectively in response to a national emergency. For instance, the early identification of multiple introductions of SARS-CoV-2 in Scotland, linking viral genomic data with epidemiological insights, was among the first of its kind globally during the pandemic. Scotland also provided some of the earliest data on the changing severity of disease associated with new variants. Additionally, the rapid identification and analysis of an outbreak of non-A-E hepatitis in children, achieved through collaboration between NHS clinicians, PHS staff, and researchers in Scottish institutions like the MRC-University of Glasgow Centre for Virus Research (CVR), exemplifies the potential for swift and effective inter-organisational cooperation. These examples highlight that such work can be expedited and enhanced if purpose-built frameworks are established ahead of emergencies.

Even outside of emergency situations, Scotland faces a persistent burden of infectious diseases, including influenza, tuberculosis (TB), respiratory syncytial virus (RSV), viral hepatitis, and various healthcare-associated infections. In order to effectively prepare for future pandemics, it is crucial that a breadth of expertise contributes significantly to the management of these ongoing public health challenges in Scotland.

This effort is valuable in its own right and also ensures that the systems, structures and relationships between the research community, health and social care providers, public health authorities, and government are well-developed and maintained. Ideally, the systems employed during emergencies should be extensions or adaptations of existing ones, supported in non-emergency times to ensure their readiness and effectiveness in future pandemic responses.

Contact

Email: scopp@gov.scot

There is a problem

Thanks for your feedback