Prohibition of the sale and supply of single-use vapes Full Business and Regulatory Impact Assessment

Business and Regulatory Impact Assessment (BRIA) for the proposed prohibition on the sale and supply of single-use vapes in Scotland.

Wider policy context

15. The Scottish Government is committed to moving towards a circular economy, where we move from a "take, make and dispose" model to one where we value materials and keep them in use. Reusable vapes are a readily available alternative to single-use vapes and have a much longer lifespan. They are made from more durable materials and are built to last longer. Although they are initially more expensive[33], reusable vapes are more cost-effective in the long term. Reusable vapes are considered to be less environmentally damaging, as the same vape can be used for an extended period of time compared to single-use vapes. Many reusable products however (e.g. carrier bags), contain more materials than their single-use alternatives, and will therefore vary in the time it takes to break-even and reduce overall material use from substitution.

16. The UK Department of Health and Social Care (DHSC) published a call for evidence on youth vaping in April 2023[34] where the impact of vapes on the environment was a key theme of interest. A summary of responses to this call for evidence was published in October 2023, highlighting many of the key issues in relation to the damaging impact on the environment caused by single-use vapes.[35] In January 2023, the Scottish Government commissioned Zero Waste Scotland to examine the environmental impact of single-use vapes. The research report, published in June 2023, highlighted environmental concerns including the increase of e-cigarette littering, waste of resources and the fire risk from batteries contained in devices, and identified possible policy options to address them.[36]

17. There are measures already in place to ensure responsible production and disposal of vapes. The Waste Electrical and Electronic Equipment (WEEE) Regulations 2013[37] aim to encourage the reuse and recycling of these items by placing financial responsibilities on producers and distributors of electrical and electronic equipment (EEE) to pay for the collection and disposal schemes for end-of-life products. This means that all producers who place EEE on the UK market, including producers of single-use vapes, are responsible for financing the costs of the collection, treatment, recovery, and environmentally sound disposal of WEEE.

18. Compliance with the current WEEE regulations by vape producers is estimated to be low. This includes low levels of awareness amongst store owners and distributors about takeback obligations, as well as low levels of customer participation reported.[38] From January 2024 vape retailers are required to provide in-store takeback for customers as vapes are now excluded from the Distributor Takeback Scheme (DTS) for Waste Electrical and Electronic Equipment (WEEE).

19. Plans to reform the producer responsibility system for waste electrical and electronic equipment[39] have recently been consulted on. Proposals under review include the provision of collection infrastructure for household WEEE financed by producers of electrical and electronic equipment; reforms to the take-back obligations that currently apply to distributors; obligations on online marketplaces; and creating a new separate categorisation for vapes to ensure producers of vapes properly finance waste management costs. The reported low awareness of producer obligations ought to be addressed by the implementation of these producer responsibility reforms.

20. To address the range of environmental issues associated with single-use vapes, the Scottish Government has decided to prohibit the sale and supply of such items (hereafter referred to as ban on single-use vapes). The Welsh Government has also agreed to this approach. The UK Government previously announced that they also plan to prohibit the sale and supply if single-use vapes but this will need to be confirmed following the UK General Election on July 4th 2024. Northern Ireland officials acknowledged the issues raised during the consultation and subsequently announced[40] in early May 2024 that it is set to ban the sale and supply of single-use vapes by April 2025. This latest development brings all four nations into line with co-ordinated legislation regarding the sale and supply of single-use vapes.

Vaping market and Scottish manufacturing

21. Based on a population share of the UK vaping industry in 2021, the Scottish industry is estimated to have a turnover of around £107 million.[41] The majority of turnover is related to the import and retail sale of devices, rather than their manufacture. For example, one of the largest vape chains in the UK now has more than 150 stores nationwide and recent reports indicate that its annual turnover has increased by almost 60% over the past five years[42].

22. The vast majority of single-use vapes are manufactured in China, with estimates of over 80% of the entire market between 5 to 6 major producers.[43] While a small amount of manufacturing may occur in the UK, we have found no evidence to indicate that single-use vapes are manufactured in Scotland.[44] In any case, the market share would be negligible. While little direct evidence exists, it is likely that any Scottish market connected to manufacturing in the vaping industry is connected to refillable products – specifically e-liquids - which are not included in the ban. Further research is needed to identify the exact nature and scale of these markets. This is most likely to be in the production and sale of e-liquids. Stakeholder engagement conducted by Defra revealed that the vast majority of e-liquid consumed in the UK is produced in the UK, therefore confirming a considerably large e-liquid production market in the UK. There is every reason to believe that, proportionally, a similar market exists in Scotland for e-liquid consumption.[45]

23. The Scottish Parliament passed the Tobacco and Primary Medical Services (Scotland) Act 2010 in January 2010.[46] The Act, amongst other things, introduced a registration scheme for tobacco retailers trading in Scotland, which became effective from 2011.[47] The Health (Tobacco, Nicotine etc. and Care) (Scotland) Act 2016[48] amended the 2010 Act to extend the requirement for registration to retailers of nicotine vapour products. From 2017, retailers selling nicotine vapour products (either solely or in conjunction with tobacco products) were therefore required to register; prior to this point registration had been voluntary. Using registration data, it is possible to observe the trend of new registrations from 2011 to June 2024. In the interests of consistency, data is analysed up until 2023 to account for only full years of data availability.

24. A limitation of using this data is that despite a legislative requirement[49] to deregister within three months of ceasing to trade or stopping selling vapes or tobacco products, not all businesses do so, particularly if the business closes permanently or changes ownership. The numbers therefore are likely an overestimate of businesses in Scotland which are selling vapes. To compensate, the numbers have been adjusted downwards by the respective annual rate of business closures (officially referred to as the “death rate”[50]) for the retail sector in the UK.

25. Registrations have been analysed both in terms of new registrations per year and cumulatively over time since 2017. The respective business death rate has been applied for each year since vape sellers have been mandated to register. This means that it is applied in separate years for new registrations, and to the running total for the cumulative measurement. As this rate reflects the rate at which all businesses (existing and new) close in any given year, it should help to adjust the cumulative number of businesses on the register each year more closely.

26. In total, there have been 7,567 total Scottish vape seller registrations since 2011.[51] 5,826 of these are businesses registered to sell both vapes and tobacco products, and 1,741 of these registered to sell vapes but not tobacco products.[52] This is compared to a total of 6,712 registrations for tobacco sellers only. Adjusted for annual rate of business closure rates, the total number of vape seller registrations falls to 6,760, with 5,206 being tobacco and vapes, and 1,554 being vapes only. The number of tobacco sellers also drops to 6,048. All data is analysed only up to 2023.

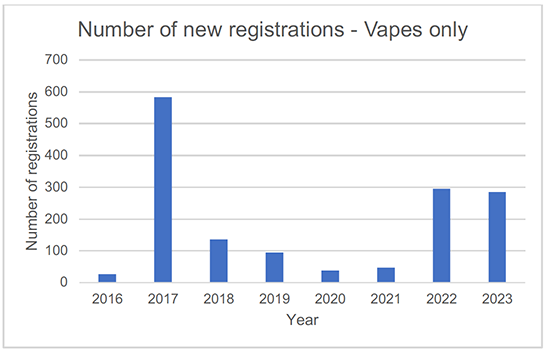

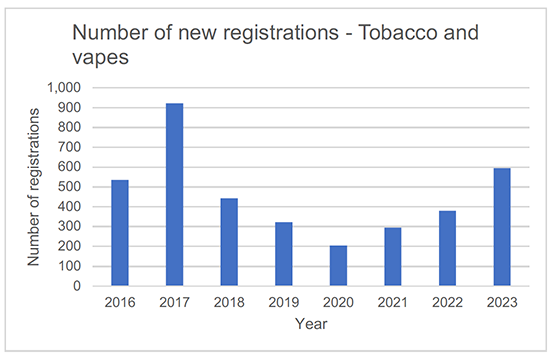

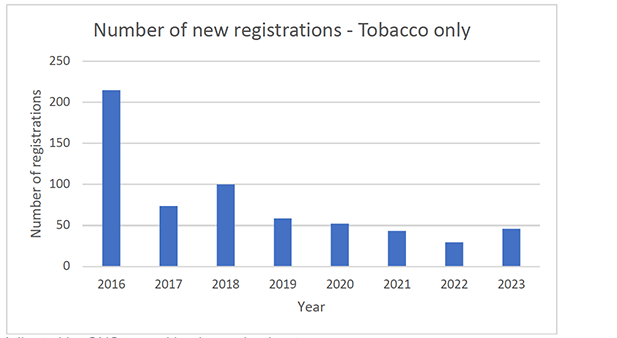

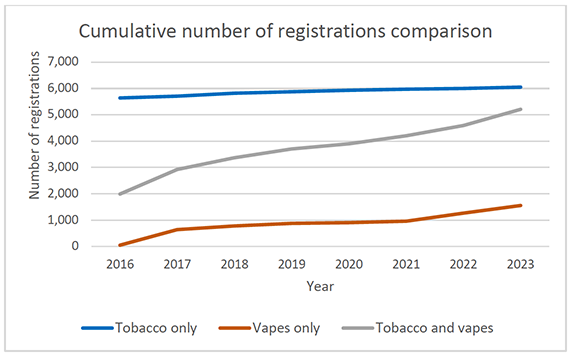

27. Figures 1, 2, 3, and 4 below show the numbers of new registrations for tobacco only, vapes only, vapes and tobacco, and the cumulative number of registrations over time for all three of these categories. As vape sellers were not mandated to be on the register until 2017, trend data has been taken from 2016 onwards to demonstrate the impact of this policy more clearly. Note that the impact of Covid-19 in 2020 and 2021 may have reduced the number of registrations in those years.

* Adjusted by ONS annual business death rates

* Adjusted by ONS annual business death rates

* Adjusted by ONS annual business death rates

| 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 | 2023 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tobacco only | 5,637 | 5,711 | 5,814 | 5,874 | 5,926 | 5,970 | 6,000 | 6,048 |

| Vapes only | 48 | 634 | 774 | 870 | 908 | 954 | 1,260 | 1,554 |

| Tobacco and vapes | 1,989 | 2,915 | 3,370 | 3,697 | 3,902 | 4,198 | 4,591 | 5,206 |

* Adjusted by ONS annual business death rates

28. It is clear from the data in Figure 1 above that there has been a significant increase in the number of new registrations in the years 2022 and 2023 for those businesses selling vapes only. This trend is partly mirrored in Figure 2 for businesses selling tobacco and vapes, although with a much smoother upward trend beginning from 2020. Figure 3 shows no such comparable trends for businesses selling tobacco only, with a mostly consistent decline since 2018. Recent socioeconomic events such as covid, the war in Ukraine, and the ongoing cost of living crisis will all have some degree of influence on these trends of business registrations due to the economic forces exerted on businesses and consumers. What is clear overall is a noticeable shift away from traditional tobacco products towards vapes.

29. Looking at the cumulative number of registrations between the three data sets, there is a similar upward trend of new registrations for all vape selling business registrations. Although beginning higher overall, growth in the number of businesses selling tobacco only has been mostly stagnant. As of 2023, the number of businesses selling vapes (with and without tobacco) is higher than the number of businesses selling tobacco only. It could therefore be expected that, based on these past and present trends, the number of businesses selling vapes will far outstrip those selling tobacco only further into the future.

30. For many years now the tobacco and vape industries have been moving inversely to each other, with tobacco declining and vaping increasing.[53] Based on this trend, it can be reasonably assumed that the growth in new registrations overall is primarily driven by the growth in those selling vapes, regardless of their registration as a tobacco and vapes retailer or vapes only retailer. In addition, given the significant uptake in single-use vape use in particular over recent years, it would again be reasonable to assume that the growth in registrations, particularly for premises only selling vapes, is being driven by the surge in popularity of single-use vapes. Although, as mentioned previously, a limitation of using the Tobacco Register data is that many businesses do not de-register when they are mandated to do so, so an exact number is not known. Given the information above on consumer habits however, overall market trends may begin to be reflected in business registrations, and those selling vapes or tobacco will begin to move inversely over time.

31. The 2023 UK-wide consultation[54] suggests that, currently, cigarettes are estimated to be on average around three times more expensive than vapes due to application of both VAT and cigarette tax. It also suggests there is a relatively wide range of costs for vapes, with single-use vapes being cheaper as a one-off purchase while reusable vapes are initially more expensive. These price differentials will however be subject to change from October 2026 when a new Vaping Products Duty is introduced by UK government. A public consultation[55] was held on this new duty which closed on 29 May 2024. It sets out the proposals for how the duty will be designed and implemented and will be accompanied by a one-off increase in tobacco duties.

32. Costs used in the consultation ranged from an average of £6 for single-use vapes to £40 for reusable versions. Reusable vapes are more expensive initially with a higher upfront purchase cost. This differs according to the type of reusable vapes, with pre-filled pods kits costing an average of £12 with the more complex refillable cartridge vapes an average of £40. Single-use vapes as a one-time purchase average around £6, making them the cheaper option in the short term.

Objective

33. The policy objectives of the intervention are to:

- Accelerate a reduction in environmental harm by reducing the number of vapes being landfilled, incinerated, and littered, and increasing recycling and reuse rates by requiring consumers to move to reusable alternatives;

- Stimulating businesses and consumers to replace single-use vapes with reusable alternatives, thereby supporting a switch to less environmentally harmful products.

34. Banning the sale and supply of single-use vapes will contribute to aims set out in the Climate Change (Scotland) Act 2009,[56] and the Climate Change Plan, Third Report on Proposals and Policies (RPP).[57] An update to the 2018 Climate Change Plan: Third RPP 2018-2032 was published in 2020 and sets out plans to achieve decarbonisation of the economy in the period to 2032, making progress towards the target of net zero by 2045[58].

35. In 2015, the Scottish Government signed up to support the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals.[59] The ambition behind the goals is to end poverty, protect the planet and ensure prosperity for all as part of a new sustainable development agenda. A ban on the sale and supply of single-use vapes will have a positive impact on a number of these goals, most explicitly Goals 12, 13, 14 and 15:

- Responsible Consumption and Production

- Climate Action

- Life Below Water

- Life on Land

36. Furthermore, the policy will contribute towards goals outlined in Scotland’s National Strategy for Economic Transformation (NSET).[60] Specifically, the vision to create a wellbeing economy. Reducing material consumption, particularly with problematic single-use items, will help to keep our economy with environmental limits, and climate and nature targets.

37. The proposed ban on the sale and supply of single-use vapes fulfils a commitment in the Programme for Government 2023/2024[61] to “Take action to reduce vaping among nonsmokers and young people and to tackle the environmental impact of single-use vapes, including consulting on a proposal to ban their sale and other appropriate measures.” Also, the proposed ban contributes to two out of five of the key priorities in the National Mission to build a fair, green, and growing economy:

- “Ensure that Scotland leads the way in tackling the climate emergency – in how we heat our homes, travel day-to-day, and use our land”.

- “Reverse decades of damage to the natural world on land and sea by helping nature fight back”.

Existing regulatory landscape

38. Producer responsibility for vapes falls under the WEEE Regulations. The majority of the WEEE Regulations came into force across the UK on 1 January 2014, implementing the main provisions Directive 2012/19/EU on WEEE.[62] In keeping with the Directive, the WEEE Regulations provided for a wider range of EEE products to be covered by the obligations in the Regulations with effect from 1st January 2019. There are ten broad categories of WEEE outlined within the WEEE Regulations, plus four sub categories[63]. Vapes currently fall under category 7 – toys, leisure, and sports equipment. A key principle in managing WEEE is the “polluter pays”[64] principle, which underpins many environmental measures.

39. The current system of WEEE Producer Responsibility (PR) is based on ‘collective producer responsibility’,[65] Unlike in an individual producer responsibility scheme, producers do not have to individually finance the collection and reprocessing of exclusively their own equipment. Rather, the entire market’s WEEE is collected, reprocessed, and collectively paid for based on the fraction of each producer’s market share, by weight, of each category of WEEE.

40. However, the costs of recycling vapes are significantly higher than other category 7 products, with estimates of the cost of recycling a single vape to be £0.4-£1.0, and with costs by weight to be £5-£10 per kilogram.[66] This categorisation means that it is likely that vapes producers will not cover the full cost of vapes collected for recycling, reducing the incentive for them to ensure that their products are easily recyclable.

41. For example, research commissioned by Zero Waste Scotland[67] found that WEEE recycling organisations were facing costs of recycling single-use vapes in the order of £0.50 per item (some organisations have been quoted £1 per item). Empty single-use vapes weigh of the order 30gError! Reference source not found., so a cost of the order £0.50 per item equates to over £15,000 per tonne. Given the previously quoted average retail cost of a vape being £6, this means that the cost of recycling a single-use vape ranges anywhere between 8% and 17% of the retail price.

42. Where vapes are collected for recycling by producer compliance schemes (for example where households return vapes to their local HWRC), there is significant risk that the other category 7 producers will share the higher cost of treating these vapes. This unfairly increases the compliance costs to those producers. The challenge for producer compliance schemes to fairly apportion costs of collection and treatment of vapes acts as a disincentive for them to sign up vape producers. The current inclusion of vapes within category 7 means that producer compliance schemes and producers do not currently need to ensure that vapes are collected to meet their recycling targets, as targets can be met through financing the collection of other category 7 items. It is unlikely that vapes producers are covering the full cost of vapes collected for recycling, which reduces the incentive for them to ensure that their products are easily recyclable.

43. When the WEEE Regulations were implemented, vape usage was low, and these products only made up a small proportion of category 7. However, there has been as significant increase in the use of vapes in Scotland, as evidenced above. Additionally, compliance with the WEEE Regulations by vape producers is estimated to be low, particularly among producers and convenience stores. Retailers that sell vapes in any quantity are obliged to offer take-back services for recycling (i.e. they must provide a vape disposal bin in store). There are low levels of awareness amongst store owners and distributors of their takeback obligations , as well as low levels of customer participation reported.

44. The WEEE Regulations, as they relate to the management of single-use vape waste, are being reviewed on a four nations basis. One of the proposed changes is to make a distinct category for vapes. The aim is to ensure that it is vape producers who pay the cost of managing single-use vaping waste, the cost of which is currently – and disproportionately – falling on local authorities and other category 7 producers. Separating out vapes from other category 7 products will ensure collective responsibility amongst vape producers for waste management costs and may incentivise them to enhance the recyclability of their products through eco-design or reduce their demand through cost pass-through to the consumers from the increase in waste end-of-life management costs.

45. Wider relevant reforms in the consultation include measures to improve the convenience for households seeking to dispose of all types of waste electricals with new responsibilities placed on producers and distributors. This includes the provision of producer financed communications over how to properly dispose unwanted items. It should be noted however that communications campaigns generally take time to change behaviour. As such, it is not expected that there will be significant additional recycled tonnage of vapes as a specific result.

46. The planned ban on the sale and supply of single-use vapes forms part of a suite of measures being taken forward by the Scottish Government to reduce our reliance on single-use items and encourage behaviour change towards re-use. This includes the implementation of the Environmental Protection (Single-use Plastic Products) (Scotland) Regulations 2021 in June 2022[68], building on the success of the single-use carrier bag charge[69], and our commitment to publish a consultation on the introduction of a minimum charge on single-use beverage cups.

47. The UK Emissions Trading Scheme (ETS) Authority – made up of the Scottish Government, UK Government, Welsh Government and the Northern Ireland Executive – is working on the expansion of the UK ETS to include incineration and energy from waste. Following a call for evidence as part of a consultation in 2022[70], the UK ETS Authority response[71] set out that inclusion of incineration and energy from waste in the UK ETS could facilitate reductions in emissions and increase efficiency of these processes. The response noted an intention to include incineration and energy from waste in the UK ETS from 2028, subject to further consultation on the details of implementation. There is a risk that Persistent Organic Pollutants (POPs) above threshold limits, may be identified in some single-use vapes (and reusable vapes at the end of their usable lives), which means they would need to be managed in line with relevant regulations and managed in a way that destroys the POP content. Currently, the main option available to destroy the POP content is energy from waste. Waste managers dealing with end-of-life vapes could, therefore be affected by the potential inclusion of energy from waste in the UK ETS scheme.

Rationale for Government intervention

48. It is expected that the implementation of a ban on single-use vapes will:

- Reduce the volume of waste created.

- Reduce the numbers of single-use vapes entering terrestrial and marine ecosystems through littering.

- Encourage wider and more sustainable behaviour change around the consumption of single-use items to tackle our throwaway culture.

- Reduce consumption of critical raw materials.

- Encourage a shift towards reusable alternatives.

49. The sharp rise in youth vaping is also of growing concern. As already noted, despite the sale of vapes to those under the age of 18 being illegal, the recent Health Behaviour in School-Aged Children (Scotland) study[72] reports that 3% of 11-year-olds, 10% of 13-year-olds and 25% of 15-year-olds said they had used a vape in the past 30 days.

Rising consumption in absence of intervention

50. Based on current and projected market trends, in the absence of intervention, it is unlikely that the consumption and subsequent disposal of single-use vapes will fall as a result of market or other forces alone. The total number of Scottish single-use vape users in 2022 was estimated at around 149,000, which could rise to 361,000 by 2027[73]. Converting this into an implied consumption of single-use vapes could equate to 26.6 million to 63.9 million, respectively.[74]

51. Single-use vapes will likely remain popular and widely available in the absence of intervention due to their convenience and ease of use. Despite there being a mature market for reusable alternatives, the popularity of single-use vapes among certain groups, particularly young people, is very likely to persist. Disposable vapes are believed to be particularly appealing to young people due to the colour packaging and product design, and range of fruity and sweet flavours on offer[75]. Many users of single-use vapes tend to be in-the-moment, ad-hoc purchasers, and vaping may be a core aspect of how some socialise with friends.[76] This social nature of vaping, akin to traditional tobacco products, means social and behavioural norms are formed around their use, making it challenging for some to give up in addition to potentially developing a nicotine dependency.[77]

52. It could be argued that, in the absence of intervention, users of single-use vapes would be incentivised to switch to reusable alternatives, given they are cheaper to use in the long-term. Given, however, that many users of single-use vapes are ad-hoc purchasers and are not necessarily using them for smoking cessation, they have less incentive to switch to reusable alternatives as might be the case for others. Furthermore, youth vapers may struggle to take them into a home environment due to risk of confiscation, and therefore benefit from single-use vapes being cheap on a unit basis and therefore easy to replace, in addition to not requiring recharging or refilling. As single-use vapes have a low upfront cost, they are more accessible to experimental users and those with limited money to spend.

Environmental, health, and social externalities

48. Due to their nature, when single-use vapes come to end-of-life, they are often disposed of in residual waste or littered, ending up either in landfill or incinerated. This is their main contribution to negative externalities. Other externalities associated with extraction of raw materials and production are not included here, as the BRIA only considers territorial effects in Scotland. Single-use vapes contain lithium-ion batteries and when disposed of improperly pose a fire risk. Fires can occur in household/commercial household waste bins, inside waste collection vehicles, or in household waste and recycling centres (HWRCs), or many other environments.

49. During waste management and recycling processes, vapes can be crushed or punctured, potentially causing them to self-combust[78], setting fire to combustible materials surrounding them. This poses health and environmental concerns both to waste management and recycling workers, and the public. The prevalence of fires linked to single-use vapes which have been improperly disposed of is likely to be costing councils and waste management businesses heavily, as well as impacting public property and land. It is estimated that lithium-ion batteries are linked to roughly half of all waste fires in the UK each year.[79]

50. In 2023, it was estimated that almost 5 million single-use vapes were either littered or thrown away in residual waste streams in the UK, almost four times as much as the previous year.[80] When single-use vapes are littered, they introduce plastic, nicotine salts, heavy metals, lead, mercury, and flammable lithium-ion batteries into the natural environment.[81] The chemicals can contaminate waterways and soil and can also be toxic and damaging to wildlife. When single-use vapes with a plastic casing are littered, the plastic can grind down into harmful microplastics. Single-use vapes are primarily littered in public spaces and this generates clean-up costs to local authorities (LAs).[82]

51. Since single-use vapes contain critical raw materials such as lithium, cobalt, and copper[83] their use and disposal creates negative environmental externalities related to the waste of not recovering critical raw materials. Lithium is particularly critical in the production of a wide range of electronic devices. At the UK level, it is estimated that five million single-use vapes are being thrown away per week, taking a population share for Scotland (8.18% of the UK total)[84], this amounts to enough lithium to make around 400 electric vehicles per year, based on a UK-wide estimate of 5,000 electric vehicles per year.[85] Other environmental externalities include greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, energy use, water use, and littering[86].

52. Littering was a key driver in the ban on certain single-use plastic items in Scotland[87] due to their persistent nature causing long-term visual disamenity and ecosystem damage.[88] Single-use vapes are a step change from other single-use plastic items as they additionally contain electronics and many other problematic materials and substances which could be hazardous to human and ecosystem health. Due to this, their visual disamenity cost is likely to be much higher where people are aware of the components and the risk of combustion and/or leakage into the environment, as well as the waste of valuable materials and energy involved in their manufacture.

53. When single-use vapes are disposed of incorrectly, potentially harmful materials and chemicals enter terrestrial and marine environments. Some materials can persist for hundreds of years causing damage to ecosystems. Chemicals added during the manufacture of plastics can enhance durability, act as a colorant, plasticizer, stabilizer or increase flame retardancy. Some of these chemicals are classified as persistent organic pollutants (POPs) and endocrine disruptor chemicals (EDCs) and will further harm terrestrial and marine life if ingested as microplastics.[89] The electronics and critical raw materials (lithium-ion batteries, copper, cobalt etc.) can also pose their own risk to human and ecosystem health.

54. From a socioeconomic perspective, littering of single-use vapes imposes direct societal costs in the form of litter clean up from local authorities and other organisations and indirect costs such as the visual disamenity of litter. Given these costs, the policy aim is to eliminate the consumption of single-use vapes and therefore reduce their negative social and environmental externalities. This can come either from consumers switching to reusable alternatives, or forgoing consumption altogether.

55. There may also be positive impacts on mental health and wellbeing if the ban is successful in achieving a reduction in litter. The Scottish Litter Survey[90] found that the effects of litter on local resident’s health and wellbeing was among respondents’ top three concerns, ranking third after the impact on animals and the environment and negative perceptions of the neighbourhood. Furthermore, the Carnegie Trust found that those who reported the highest incidence of environmental incivilities such as litter were more likely to report anxiety, depression, poor health, smoking, and poor exercise than those with more positive views on this aspect of their local environment[91]. Another study[92] investigated the effect of litter on psychological reactions to marine environments. The study found that photographs of un-littered coasts tended to provide participants with a sense of happiness and less stress while photographs exhibiting littered coasts caused participants to exhibit stress and a lack of the positive psychological benefits that coastal environments normally provide.

56. With negative externalities in mind, single-use vapes are emblematic of the linear economy, where they are manufactured and sold purely on the basis of generating private profit at the expense of environmental and societal wellbeing; the traditional “make, use dispose” approach.[93] Their linear design, manufacturing, and consumption present a barrier to achieving circularity in Scotland, and their continued consumption poses a risk of setback on achieving a more sustainable economy and society. Even if they are recycled, this is still not an efficient use of resources which could otherwise be put to better use, especially given the high costs of recycling which makes it uneconomical in many circumstances. In contrast, reusable vapes can typically last through 300 charge cycles.[94] For the typical user, a reusable vape will last between several months to over a year. This is in contrast to the limited longevity of single-use vapes. Most disposable vapes contain around 600 ‘puffs’, as most, if not all, contain the maximum legal limit of both volume and strength of nicotine liquid[95].

Information failure

57. Information market failures exist. Despite single-use vapes being covered by WEEE Regulations, there are low levels of consumer awareness over the environmental and health impacts of incorrect disposal and a lack of knowledge, and willingness, to pursue correct forms of disposal.[96] 45% of UK households are unaware of the fire risk posed by incorrect disposal of single-use vapes, and 40% are unaware of any information regarding safe disposal of batteries, including those found in single-use vapes. It is estimated that 70% of people throw away single-use vapes because they did not know they could be recycled.[97] It must be noted that information failure does not form the main basis for intervention, as overcoming this failure would not change the linear design of single-use vapes, which perpetuates the issue of unsustainable resource use.

58. The opacity and frequent changes, in addition to the diversity of companies involved in the importation and distribution, makes the UK vape market complex to understand. Low barriers to entry allow new and opportunistic companies to import vape products. The innovation and the development of new types of vaping products provides opportunities for new entrants to satisfy demand for novel and innovative products. The market has grown rapidly and is likely to continue developing, with a high number of new entrants bringing products to the UK market and a range of retail channels bringing products to consumers.[98] Large sections of the vape market are illicit and is therefore not accurately recorded. Estimates from industry stakeholders suggest that the size of the illicit market could be on par with that of the legal counterpart[99].

Lack of compliance

59. This lack of information and complexity has contributed towards a lack of regulatory compliance with products on the market which exceed the legal level of nicotine or circumvent the minimum product safety standards. The highest strength legally allowed in a single-use vape in the UK is 20mg (2%) and 2ml, so 40mg of nicotine in total.[100] Trading Standards have seized single-use vapes entering the UK containing far above this legal limit.[101] Around 99% of seized illegal vapes were single-use, as confirmed by Trading Standards.[102] This poor compliance extends to retailers and other businesses selling single-use vapes to the public. The most common method for those aged under 18 to buy vapes is from shops.[103] This is illegal and ongoing enforcement will be required.

Lack of recycling infrastructure and capacity

60. Current estimates indicate that only 17% of vape users in the UK correctly dispose of their single-use vapes.[104] Of the single-use vapes returned to a store or HWRC, it is estimated that only 1% are recycled due to limited recycling capacity.[105] When single-use vapes are recycled, the cost of doing so is high per item and by weight. In addition, the costs of recycling vapes are significantly higher than other category 7 products, with estimates of the cost of recycling a single vape to be £0.40-£1, and with costs by weight to be £5-£10 per kilogram.[106]

61. Current UK-wide estimates for the cost of collecting and recycling these vapes is £200 million per year.[107] If it is assumed that the consumption of single-use vapes can be divided up reliably by population share, i.e. Scotland at 8.06%, the costs attributed to Scottish LAs, government, organisations, and society for the collection and recycling of vapes would be £16.12 million per year.

International examples

62. There is growing international momentum to restrict the sale and supply of single-use vapes. In the European Union, the Battery Regulation requires, from 2027, that portable batteries in most electronic devices (such as e-cigarettes/vapes), must be removable and replaceable by the users themselves.[108] Single-use vapes which do not currently meet these requirements will be prevented from being placed on the market in the EU as of 2027.[109]

63. The French government is considering a ban[110] on single-use vapes amid health and environmental concerns, which is likely to come into effect by September 2024. Ireland and Germany are also considering bans on single-use vapes due to their concerns about environmental impacts and disposal issues.[111] Belgium will become the first EU member state to ban single-use electronic cigarettes from 1 Jan 2026 following the European Commission’s recent approval of its draft legislation.[112]

64. The sale of all e-cigarettes with a flavour other than tobacco is banned in Finland, and restrictions apply to advertising and promotion at points of sale. In Norway, sales of e-cigarettes and e-liquids are restricted to instances where the product has been approved by the Directorate of Health. Domestic sale of flavoured vapes is also banned in China, though their manufacture for export is permitted.[113]

65. New Zealand introduced a ban on single-use vapes in 2023 requiring manufacturers, importers, distributors, and retailers to only sell single-use vaping products that have a removable battery, a child safety mechanism, follow new nicotine concentration requirements, and comply with new labelling requirements.[114] Further restrictions include limiting vape products and their packaging to only allow generic flavour descriptions and prohibiting new specialist vape shops from opening in the immediate vicinity of schools. In March 2024, the New Zealand Government announced they would be banning all single-use vapes in an effort to prevent minors from taking up vaping.[115]

66. Australia has also taken action to limit the use of vapes through stronger legislation, enforcement, education, and support. From October 2021, a prescription is required to lawfully access vapes containing nicotine in Australia[116] and imports of single-use vapes were banned from January 2024.

67. Other countries, such as Qatar and Singapore, banned the use of vapes in their entirety, whereby the possession or sale of them can result in a penalty fine. More information on international legislation restricting the sale and supply of vapes is provided on the Tobacco Control Laws website.[117]

Alignment with health objectives

68. In 2013 the Scottish Government launched ‘Creating a tobacco-free generation: A Tobacco Control Strategy for Scotland’.[118] It contained the ambitious aim of making Scotland tobacco-free (population smoking prevalence of 5% or less) by 2034 (hereafter referred to as the 2034 target). The 2018 Tobacco Action Plan “Raising Scotland’s tobacco-free generation: our tobacco control action plan 2018” [119] was launched by the Scottish Government in June 2018 superseding but building on the 2013 Strategy. This five-year action plan set out further interventions and policies to help reduce the harms from tobacco in Scotland.

69. In 2022, work began to develop a new action plan ‘Tobacco and Vaping Framework: Roadmap to 2034’ (published in 2023), which sets out the Scottish Government’s commitment to the original smoke free 2034 target. This long-term Framework is underpinned by a series of two-year action focused implementation plans. This first implementation plan will run until November 2025.

70. The Tobacco and Vaping Framework recognises the rapidly changing landscape in Scotland, especially around the rise in popularity of vapes, where there should be a joint focus on the harmful effects of tobacco and vapes.

71. There are three themes within the Framework focused on people, product and place. Although a ban is progressing through environmental regulations it is consistent and complementary to the wider strategic health focus contained with the Framework, which includes working across the UK on policy interventions, where possible.

Alignment with National Performance Framework and other strategies

72. Eliminating the consumption of single-use vapes will contribute towards delivering the strategic aims within the Scottish Government’s draft Circular Economy Route Map[120], and forms part of the system-wide vision to accelerate more sustainable use of our resources across the waste hierarchy between now and 2030.

73. With reference to the National Performance Framework (NPF)[121], the proposed legislation is directly applicable to the following National Outcomes:

- We value and enjoy our built and natural environment and protect it and enhance it for future generations.[122]

- We reduce the local and global environmental impact of our consumption and production.[123]

74. The Circular Economy (Scotland) Bill[124] as introduced, includes measures to establish a legislative framework to support Scotland’s transition towards a circular economy. The Circular Economy (Scotland) Bill completed Stage 2 in the Scottish Parliament on 28 May 2024. The Bill includes provisions to require Scottish Ministers to publish a strategy for a circular economy and thereafter revise and re-publish the strategy at least every 5 years and enables regulations to impose circular economy targets on the Scottish Ministers. Additional provisions include:

- Powers to restrict the disposal of unsold goods;

- Presenting local authorities with new powers and responsibilities in respect of the collection of household waste, including allowing Scottish ministers to set local authority recycling targets;

- More enforcement powers to tackle littering and fly-tipping;

- Improvement of waste and surplus monitoring; and

- Powers to introduce charges for single-use items.

75. The Bill aims to accelerate Scotland’s journey towards a circular economy, and the proposed ban on single-use vapes aligns with this ambition by phasing out single-use vapes and encouraging the adoption of reusable alternatives.

76. The Scottish Government launched a consultation on Scotland’s draft Circular Economy and Waste Route Map to 2030[125] in January 2024. The Route Map sets out how Scotland should deliver its circular economy ambitions, including making use of the proposed new powers included in the Circular Economy (Scotland) Bill.

77. Measures in the Route Map are grouped under four strategic aims, which reflect the span of the waste hierarchy:

- Reduce and reuse (including a commitment to ‘consult on actions regarding the environmental impacts of single-use vapes’.);

- Modernise recycling;

- Decarbonise disposal; and

- Strengthen the circular economy.

Contact

Email: productstewardship@gov.scot

There is a problem

Thanks for your feedback