Putting Families at the heart of Family Visa Policy

Scottish Government response to the Migration Advisory Committee's Call for Evidence on family visa financial requirements.

Comment on the level of the current minimum income/financial requirements

1. The Scottish Government does not consider that there should be a minimum income requirement in place for those individuals who have a right to live in the UK. If there was a desire to retain a minimum income threshold then urgent action should be taken to significantly reduce the current level. Any increase in the minimum income threshold as proposed by the previous UK Government should be resisted.

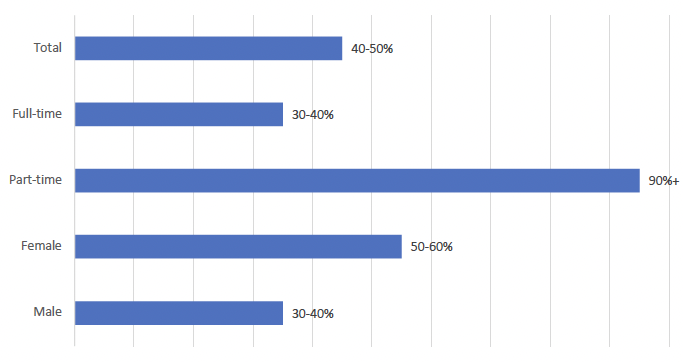

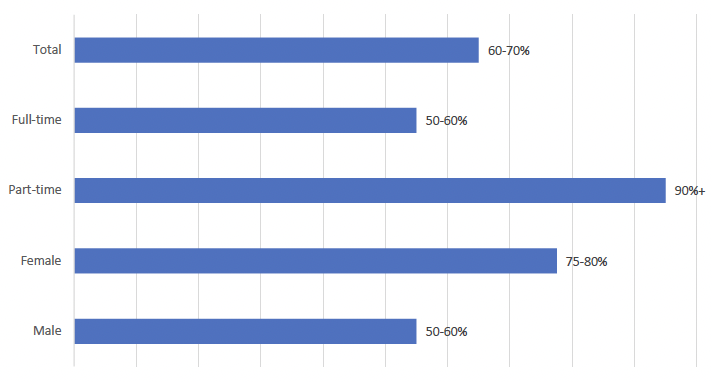

2. The Annual Survey of Hours and Earnings (ASHE) provides information on the gross annual income of employees in Scotland, split by local authority, gender and full-time vs part time. Analysis of this data shows that 40-50% of employees in Scotland currently earn below the £29,000 minimum earnings threshold. This rises to 50-60% of employees when considering the £34,500 threshold, and 60-70% of employees for the £38,700 threshold. A higher proportion of women and part time workers earn below any given threshold, again highlighting the equalities issues associated with the current salary threshold.

3. On the basis of these figures over 50% of women employed in Scotland would not meet the current minimum income threshold to sponsor a family member. This data gathers information on employees so would not include those not currently in employment. Over 90% of part time workers do not meet the current minimum income threshold to bring a family member into the country on a Family Visa.

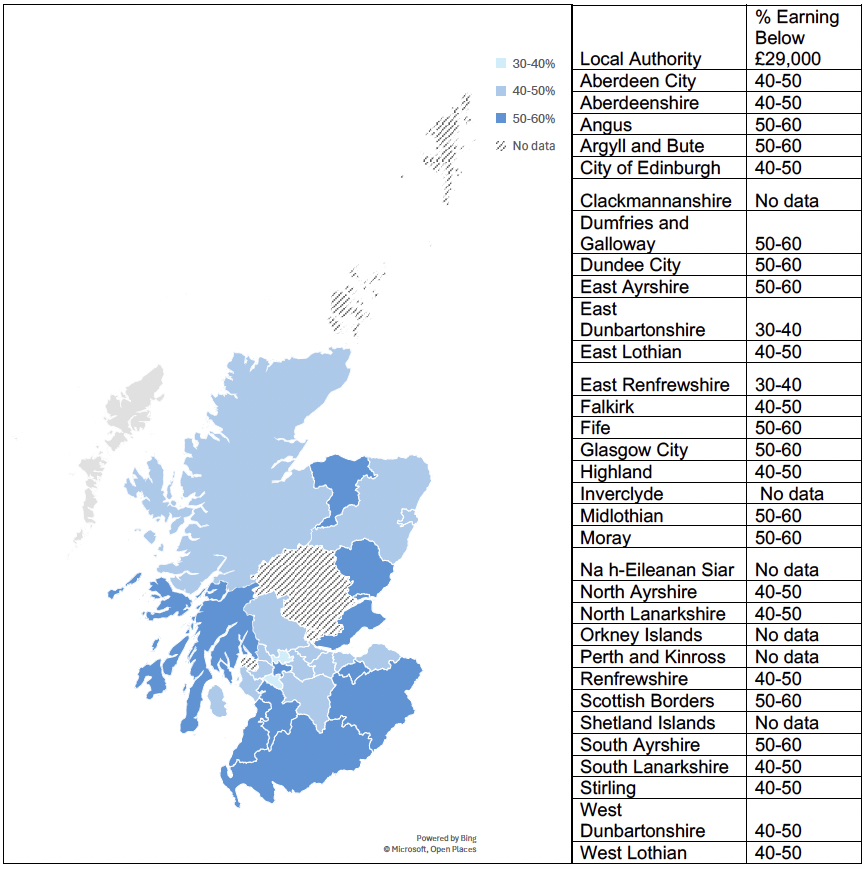

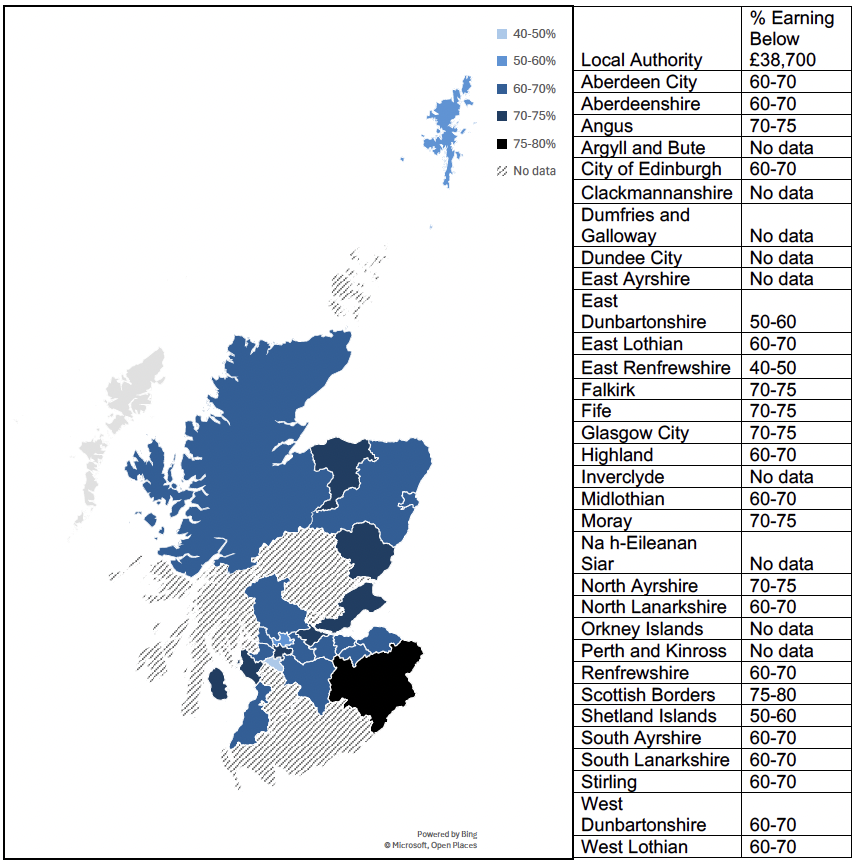

4. In addition to divergence by gender there is also a geographical divergence. We do not have ASHE data for every local authority. However, in half of the Scottish Local Authorities for which data is available, 40-50% of employees earn below the £29,000 income threshold, and in 42% of local authorities 50-60% of employees earn below this threshold. Unfortunately, we do not have data from a number of our island authorities, but it is known that “very few roles in remote and rural geographies meet currently required salary thresholds"[14] and are therefore impacted in their capacity to recruit international workers by the existing salary threshold. This would therefore equally apply to ability to sponsor a family member.

5. Detail on the geographical breakdown of ASHE data is set out below.

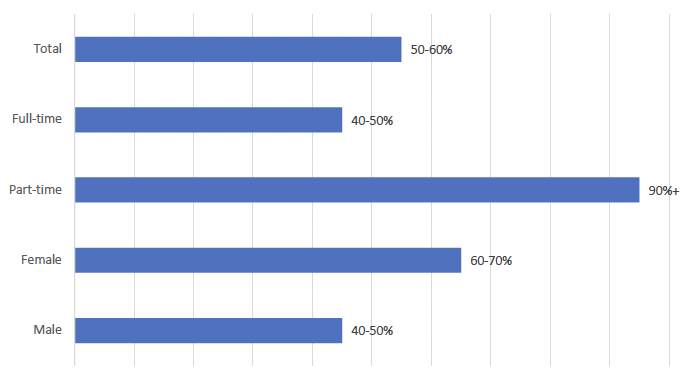

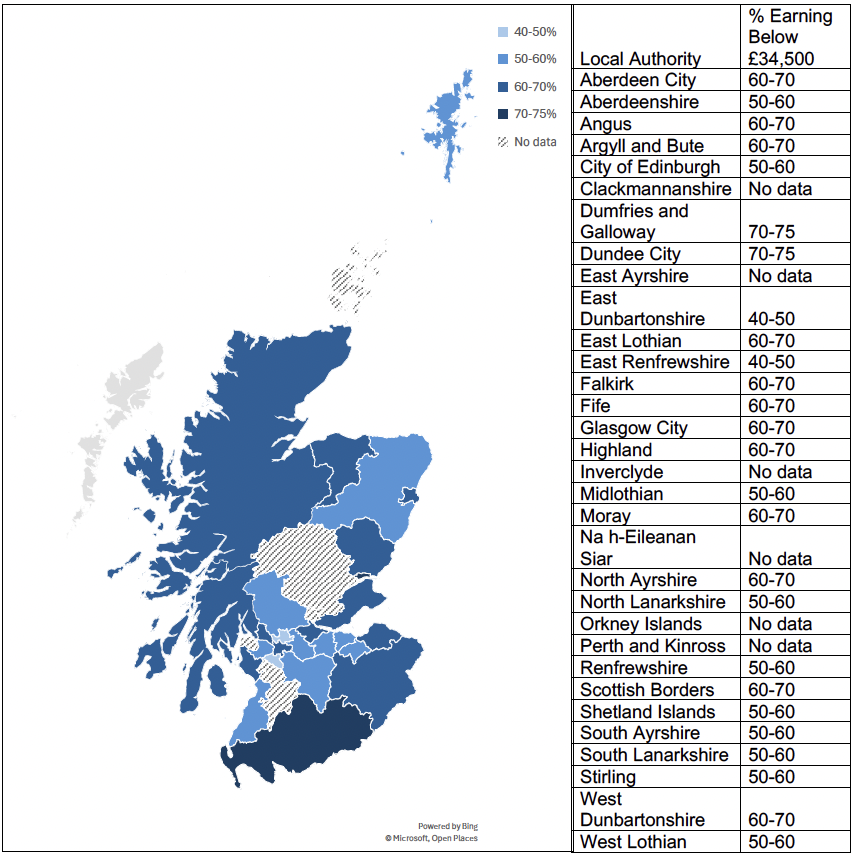

6. The previous UK Government announced an intention to increase the financial threshold. The ASHE data indicates that 50-60% of employees would not be able to meet a £34,500 threshold allowing them to sponsor a single family member. If the minimum income threshold was raised to this level over half of all employees in Scotland, and over 60% of women, would not be able to sponsor a single family member through the Family Visa route.

7. When taking a similar look at the geographical impact of the £34,500 threshold, in 39% of local authorities 50-60% of employees earn below this level, and in 46% of local authorities, including Aberdeen City and Glasgow City, 60-70% of employees earn below this level. In Dumfries and Galloway, and Dundee City, 70-75% of employees earn below £34,500, whilst in East Dunbartonshire and East Renfrewshire 40-50% employees earn below this threshold.

8. The previous Government had announced an intention to increase the minimum income threshold to £38,700 by early 2025. If that increase was to be implemented then 60-70% of employees in Scotland would not meet the minimum income threshold to sponsor a family member. This rises to 75-80% of women.

9. As in the previous examples there would be a geographical divergence in the ability of individuals to bring family members into the UK through the family visa route. Only 20-25% on employees in the Scottish Borders would be able to sponsor a family member through the Family Visa route. Only 20-25% of employees in Glasgow would meet the minimum income threshold. Those percentages would be significantly lower for women.

10. The information above provides details on employee salary levels on the basis of geography, where that data is available; fulltime/part time work and gender. There is also evidence of a disability pay gap. Analysis by the Office for National Statistics[15] found that the pay gap between disabled and non-disabled employees was 12.7%. The disability pay gap was wider for men (15.5%) than for women (9.6%) and for full time employees (11.2%) than for part time employees(4.1%).

11. Scotland has distinct demographic challenges, yet the Family Visa route is a barrier to people moving to Scotland, especially some of our areas which are most at risk of depopulation. UK citizens who cannot afford to bring a family member to the UK through the family visa route and do not wish to be separated from their family face being effectively exiled.

How effectively does the Minimum Income threshold test meet the policy aim of balancing respect for family life with maintaining the economic wellbeing of the UK, protecting the public from foreign criminals and protecting the rights and freedoms of others.

1. The Scottish Government does not consider that the minimum income threshold test meets the policy objectives that have been set out.

2. The approach taken by previous UK Governments in introducing a minimum income threshold takes too narrow an interpretation of the economic wellbeing of the UK. It focuses solely on the salary level that a sponsor needs to earn but takes no account of the wider fiscal impact of family migration or family separation. It does not reflect the contribution a spouse may make to the economy through their own earnings or future contributions from children. It also does not reflect the potential loss of contributions if the sponsor in the UK chooses to leave the UK in order to maintain family cohesion or reduces their working hours in order to care for a child as a single parent. The narrow focus on salary does not reflect the wider social or economic impact of fractured families. In families separated by the Family Visa minimum income rules earnings made by the family member present in the UK are more likely to be sent out of the UK, rather than spent domestically. In circumstances where parents are unable to live in the same country this may impact on the ability to access employment; manage childcare and the wider economic wellbeing of the family.

3. This wider economic contribution is likely to be particularly keenly felt in rural or island communities, yet the evidence indicates that individuals in those communities are likely to be least able to sponsor a family member to enter the UK.

4. There is also evidence that the minimum income threshold disproportionately impacts women and younger people. Inevitably it takes no account of future earnings potential as individuals at an earlier point in their working lives are less likely to have reached their earning peak and thereby be more at risk of not meeting the threshold but potentially have a greater lifetime financial contribution which is not assessed through this crude measure.

5. The Scottish Government does not consider that the minimum income policy gives sufficient priority to family life. Family Visa policy should place the best interests of the child at its heart, but the current minimum income threshold risks significant negative consequences for children facing separation from a parent. In some instances, it may be a number of years before migrants are able to bring their families to the UK. Research from the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) has demonstrated that this can adversely impact children’s language learning, school attainment and longer-term educational and labour market performance in the host country (OECD 2017[16]). This impacts not just on the outcomes of the individual child but also has a wider economic and societal impact which is not reflected in any policy assessment.

6. We do welcome the decision of the previous Government to remove the additional element for children in the minimum income threshold. However, the decision to increase the overall minimum income threshold above inflation removes any benefit from the removal of the child element.

7. It is important that the immigration system has safeguards in place to protect the public from foreign criminals. Scottish Ministers are absolutely clear that migration should be controlled to deter and prevent abuse, fraud and criminal activity, including terrorism, human trafficking and other serious offences. However, it is unclear how the minimum income threshold helps to keep the public safe. There is clear evidence that the policy is discriminatory in terms of geography, gender, age and ethnicity. Making judgements on potential criminal activity on the basis of such a policy is therefore hugely problematic.

8. Making judgements about criminality based on the earnings of the sponsor in the UK is not an effective route to assess criminality, especially given the significant equalities issues raised by the minimum income threshold. The Family Visa route, as with all visa routes, needs to have measures in place to address potential criminality but this is not an effective measure for that policy objective.

Comment on how do these tests work in practice and potential unintended consequences.

1. It is common for migrant families to send a ‘pioneer’ to a new country first before deciding whether other family members will follow; this may depend on whether practical issues of securing income, accommodation and so on have been resolved. However, in reality this can often take longer than families have anticipated, resulting in an extended period of separation, which can have a range of both practical and emotional challenges.

2. For many families this will involve the ‘pioneer’ migrant working to build up sufficient income to act as a sponsor and/or seeking to switch to a more accommodating visa route, while other family members may visit on tourist or family visitor visas and then seek ways to stay for longer, or to find employment and apply for a working visa. In some scenarios, overly restrictive rules can lead migrants to pursue irregular migration as a means of reuniting their family, which may introduce complications in the longer term such as poverty, inequality, and irregular status of adults who arrived through irregular migration as children.[17]

3. In light of the demographic challenges facing Scotland it is in the country’s best interests to facilitate the migration of families as a single unit in order to support integration into local communities. Family migration rules which require UK citizens to choose between living in their nation or with their family act directly contrary to Scotland’s distinct demographic challenges. At an economic level a family living together in Scotland is likely to spend more of their earnings within the UK, rather than sending money earned within the UK to family members based in other countries who are prevented, through the conditions of the Family Visa, from living in the UK. The lost spending potential for local communities and the domestic economy is an economic factor that does not appear to have been considered. At a social and community level fractured families will often face additional barriers both economic, if wages are being split between households in different countries or practical if the absence of one parent makes it more difficult to balance family and work life to fully engaging in community life.

4. The challenges inherent in the UK’s current family migration policies also impact the spatial distribution of migration across Scotland. While those living in urban areas are paid higher wages and would be more likely to meet the threshold, in rural and islands areas, which constitutes significant areas of Scotland, incomes regularly fall below the minimum threshold. This may compound existing imbalances in the geographic spread of migration across different types of areas. This is particularly challenging in the Scottish context where many rural and island communities are experiencing acute depopulation and population ageing, which introduces a knock-on effect for public service funding and provision, and in turn the viability of these communities.

5. Rural communities in particular would benefit from bespoke migration schemes to encourage migrants and their families to settle there, in order to help mitigate the effects of population ageing and decline, as migrants tend to be of childbearing age or to already have a family. International examples of similar schemes include the Canadian Arctic Immigration Program and the Rural and Northern Immigration Pilot, as well as the Scottish Government’s own proposal for a Rural Visa Pilot.

Contact

Email: migration@gov.scot

There is a problem

Thanks for your feedback