Quality prescribing for antidepressants: guide for improvement 2024 to 2027

Antidepressant prescribing continues to increase in Scotland with one in five adults receiving one or more antidepressant prescriptions in a year. This guide aims to further improve the care of individuals receiving antidepressant medication and promote a holistic approach to person-centred care.

1. What is the purpose of this advice?

Background

This advice is intended to support healthcare professionals and those that provide support to people on antidepressant treatment to facilitate the appropriate use of antidepressants. It is not intended to override other prescribing and treatment advice such as NICE, British Association for Psychopharmacology (BAP), or Scottish Government Polypharmacy guidance, which follows the principles outlined in the Realising Realistic Medicines report. It is intended to complement and add practical advice and options for tailoring care to the needs and preferences of individuals.

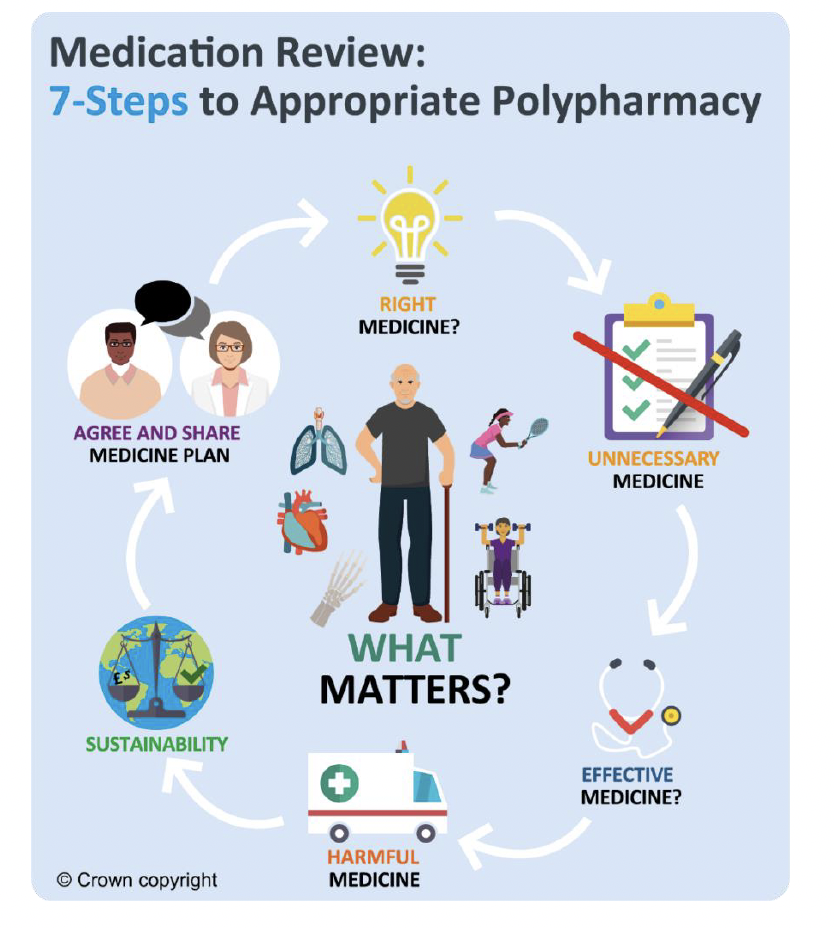

Antidepressants are used for a variety of conditions and are commonly prescribed for people experiencing a range of comorbidities and diseases. This guide provides a range of options for individuals and clinicians to support proactive person-centred antidepressant reviews. From antidepressant initiation to treatment follow up and cessation, it includes advice for shared treatment plans, managed reduction and discontinuation of therapy for adults using a person-centred approach using the 7-Steps process.

What is the benefit of this prescribing advice to the person receiving an antidepressant?

This quality prescribing advice is intended to encourage supportive and constructive discussions between individuals and prescribers when reviewing antidepressants and their ongoing need. Where appropriate, the fears and apprehensions associated with initiation, continuing, reducing or stopping antidepressants should be considered and treatment tailored to the individual’s needs.

As with all medicines – not just antidepressants – it is important to routinely and proactively monitor and review the ongoing needs and rationale for continued medicine use. Use the 7-Steps medication review process. For some individuals this may be on annual basis as part of their long-term conditions review (diabetes, asthma, etc.) while others may require more frequent reviews. However, it is known that long-term antidepressant use is increasing, [2], [3] and that the longer someone receives an antidepressant the less frequently it, or the condition it is treating, is reviewed. [4], [5] This can lead to inappropriate long-term prescribing for some individuals.

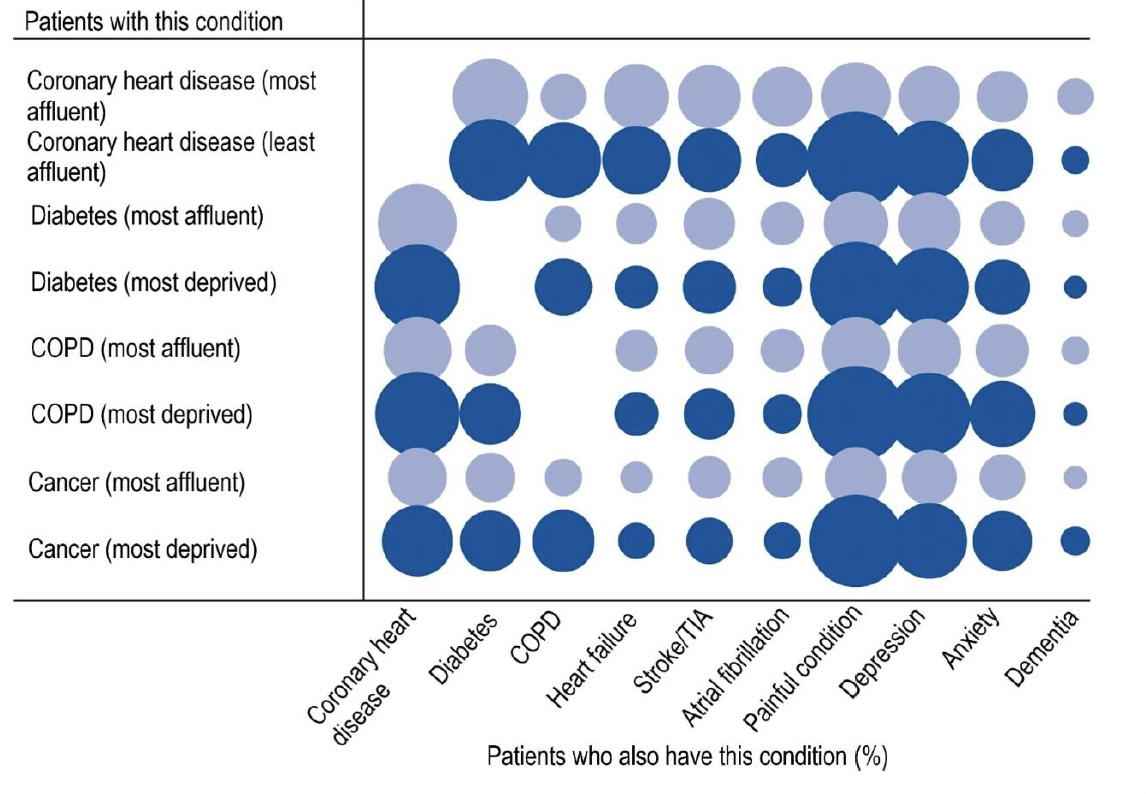

A large proportion of people with depression (receiving an antidepressant) have other comorbidities such as diabetes, cardiovascular disease, respiratory disease and therefore receive multiple prescribed medicines (known as polypharmacy). [6], [7]

This is shown in Figure 2 comparing the likelihood in the most affluent and most deprived areas. These individuals may also be frail and more likely to experience adverse drug effects and avoidable harms. Therefore, proactively reviewing antidepressant therapy creates an opportunity for a holistic person-centred assessment and review of the condition and medicine needs using the 7-Steps process. This can help reduce avoidable medication-related harms.

Comorbidity |

CHD |

Di |

COPD |

HF |

S/TIA |

AF |

PC |

Dep |

A |

Dem |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Coronary heart disease (most affluent) |

- |

19 |

7 |

14 |

13 |

12 |

16 |

13 |

9 |

4 |

Coronary heart disease (most deprived) |

- |

23 |

19 |

16 |

14 |

10 |

32 |

21 |

13 |

3 |

Diabetes (most affluent) |

21 |

- |

4 |

6 |

9 |

6 |

14 |

13 |

7 |

2 |

Diabetes (most deprived) |

24 |

- |

11 |

6 |

10 |

5 |

28 |

21 |

10 |

2 |

COPD (most affluent) |

15 |

9 |

- |

6 |

8 |

6 |

15 |

14 |

10 |

3 |

COPD (most deprived) |

24 |

13 |

- |

6 |

9 |

5 |

31 |

23 |

15 |

2 |

Cancer (most affluent) |

12 |

8 |

5 |

3 |

6 |

5 |

12 |

10 |

7 |

2 |

Cancer (most deprived) |

17 |

12 |

13 |

4 |

7 |

5 |

29 |

19 |

12 |

3 |

Key: CHD – Coronary heart disease; Di – Diabetes; COPD - Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; HF - Heart failure; S/TIA - Stroke/TIA; AF - Atrial fibrillation; PC - Painful condition; Dep – Depression; A – Anxiety; Dem - Dementia

This guidance focuses on the quality prescribing of antidepressants to result in improvements in care. The 7-Steps medication review process promotes a shared decision-making approach to medicine reviews and places the individual at the centre, to ensure prescribing is effective and appropriate for them. People will be encouraged to self-manage their condition where appropriate and be asked ‘what matters to you?’[8] to support a holistic approach to care in line with the Scottish Government’s polypharmacy guidance. [9]

Some prescribers may be less comfortable reviewing psychotropic medicines such as antidepressants and individuals may be fearful of reducing and stopping antidepressant therapy. This may be due to concerns about relapse or recurrence of their illness, and/or experiencing antidepressant discontinuation/withdrawal symptoms, all of which may result in inappropriate long-term use where treatment is no longer required.[5], [10], [11],[12], [13], [14],[15], [16] Proactive medicines reviews also create an opportunity for people to be directed to and access non-pharmacological and psychological interventions, which may be needed to achieve better longer-term outcomes. [17],[2]

Overall, proactive medicines reviews will help to:

- reduce inappropriate medicines use e.g. where medicines are no longer needed

- reduce avoidable adverse drug effects and harms

- optimise care and outcomes

- enable people to take the medicines they need

- direct to non-pharmacological interventions where appropriate

Where appropriate, and when applied to practice, this prescribing advice may help provide structure to support people who are anxious about reducing and/or stopping antidepressant therapy, and who worry about discontinuation/withdrawal symptoms.

‘Discontinuation symptoms’ or ‘withdrawal effects’?

The term ‘discontinuation symptoms’ is used to describe symptoms experienced on stopping medicines that are not drugs of dependence. There are important semantic differences in the terms ‘discontinuation’ and ‘withdrawal’ symptoms – the latter implying addiction, the former does not. [18] While the distinction is important for precise medical terminology, it is irrelevant when it comes to personal experiences and how an individual may describe their signs and symptoms. Regardless of this, proactive medicines reviews create an opportunity for individuals and prescribers to discuss and address potential fears and worries, alongside developing appropriate shared management plans for the use of antidepressants and other medicines as part of a realistic prescribing plan.

What are the benefits of this prescribing advice to healthcare professionals?

This prescribing guide provides practical structured advice and examples of good practice approaches for health professionals to:

- identify individuals who may benefit from review (see List 1)

- review antidepressant therapy and

- routinely support people in their care

Prescribers have identified and reported that it can be:

‘…easier to start [psychotropic medicines] than to stop [them]’[10]

and that

‘…what we’re [prescriber] probably not good enough, at the moment, is sort of the long-term managing and the coming-off part’[14]

This may be due to a range of perceived and actual barriers, such as some healthcare professionals lacking confidence, knowledge and skills to support and enable proactive antidepressant review and discontinuation.[10],[13],[14],[16],,[19] Lack of knowledge may include time to onset of action,[5] as antidepressants demonstrate their effects within one to two weeks of use.[18], [20] Despite this, some prescribers wait eight weeks or more before optimising doses or switching antidepressant treatments in poor or non-responders.[5], [21]

Identifying individuals for review can be limited by some of the electronic clinical systems routinely used in clinical practice. However, the Scottish Therapeutics Utility (STU) has been developed for use in general practice in Scotland, to identify people who may benefit from a medication review. General practice staff can routinely use STU to identify and plan antidepressant review work. While there is no consensus on the optimal method for antidepressant withdrawal, [22], [23] this guidance provides a range of options for reducing and withdrawing antidepressants. More detail is available in Section 5.

What are the benefits of this prescribing advice to organisations?

Implementation and use of this advice will help improve care and outcomes with:

- a range of prescribing indicators and measures which focus attention and resources on areas that would benefit from action

- resources and examples within the case studies of what has already been trialled in clinical practice

These measures will be of use to health boards, health and social care partnerships (HSCPs), general practice clusters and individual general practices.

Why is proactively reviewing antidepressants important?

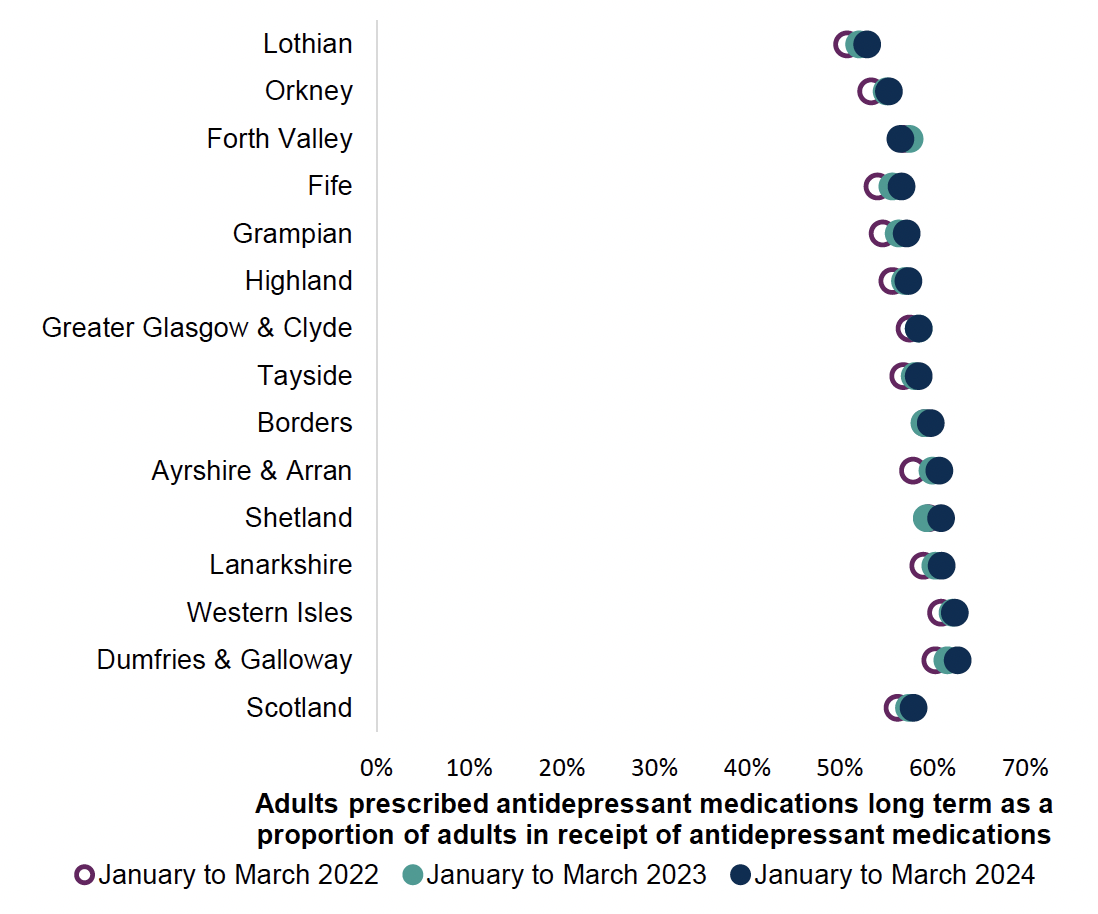

In Scotland, as with other Westernised societies, antidepressant prescribing has increased over the last 30 years and continues to increase,[1] with one in five adults receiving one or more antidepressant prescriptions in a year, and more than half of those (six in ten adults) receiving long-term (≥2 years) treatment (Chart 1).[1]

This has been due to:

- the availability of different antidepressants,[24],[25] some of which are better tolerated and safer than others [26],[27]

- people’s expectations[28], [29] and changes in society’s attitudes towards mental health conditions[30]

- greater willingness to prescribe for a variety of mental health and non-mental health conditions [31,[32], [33]

- increased long-term use,[20] and use of higher doses[17],[34]

- lack of regular medicine reviews[5,35]

- more people receiving antidepressant therapy[1]

While the majority of antidepressants are prescribed for the treatment of ‘common mental health conditions’ such as depression and anxiety disorders, they are usually only one aspect of a complex multidimensional treatment plan to care for and support people to achieve recovery.[20],[36] The lack of regular review reduces the opportunity to advise the use of non-pharmacological approaches that may aid in recovery and can lead to inappropriate long-term antidepressant use.[5],[36],[37], [38],[19]

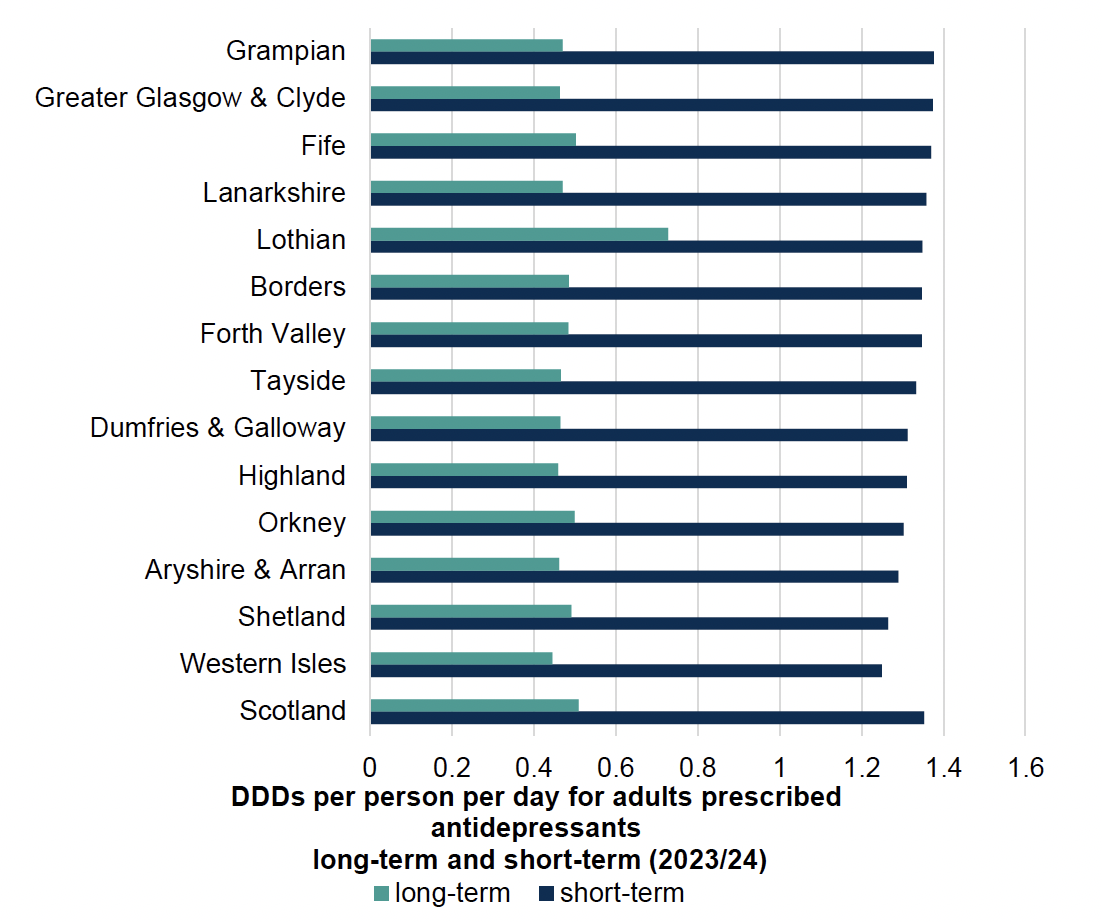

Long-term antidepressant use is associated with the use of higher antidepressant doses (Chart 2), and while this may be appropriate for some antidepressants, it can be inappropriate for others.

For example:

- Selective serotonin re-uptake inhibitors (SSRIs) demonstrate a flat dose response curve for the treatment of depression.

- standard daily doses: 20mg citalopram/fluoxetine/paroxetine, 50mg daily of sertraline or 10mg escitalopram provide optimal antidepressant effectiveness – ‘20’s plenty and 50’s enough’[20], [39], [40], [41], [42]

- as individuals may not be proactively reviewed when stable and well, presenting only at times of crisis, this may lead to doses being inappropriately increased in response to the crisis[5]

- for SSRIs, higher than standard doses are known to cause more adverse effects and avoidable harms (i.e. anxiety, insomnia, falls, etc) and are possibly associated with more withdrawal effects.[20,39-42], [43] Higher than standard doses are not more effective at reducing depressive symptoms in poor and/or non-responders [41],[42], [44],[45],[46]

- Mirtazapine also demonstrates optimal effects for the treatment of depression at 30mg daily[40]

- Tricyclics antidepressants (TCAs) demonstrate a dose response for the treatment of depression where higher doses can be more effective e.g. increasing to 100mg to 125mg per day.[18],[20],[39]

- doses as low as 10mg daily can be effective for the treatment of neuropathic pain, while 50mg to 75mg daily provide optimal effects for the majority of people with neuropathic pain[33], [50]

- higher doses are known to cause more adverse drug effects and avoidable harms such as sedation, confusion and QTc prolongation, amongst others [51]

Note: QTc prolongation: QTc prolongation is of concern as it is associated with ventricular tachycardia and sudden cardiac death. The QT interval on an electrocardiogram describes the manifestation of ventricular depolarization and repolarization. The QT interval is influenced by heart rate therefore the QT interval should be measured for rate correction, allowing the calculation of the corrected QT interval (QTc). Intervals of 440 to 460 milliseconds in men and 440 to 470 milliseconds in women are considered to be at the top limit of normal range. Bazett’s formula is considered the gold standard for QTc calculation. QTc prolongation is associated with ventricular tachycardia and sudden cardiac death.[50]

- Serotonin and noradrenaline re-uptake inhibitors (SNRIs) demonstrate a dose response effect for the treatment of depression where higher doses can be more effective.[20],[40],[49], [52], [53], [54]

- For example, venlafaxine exhibits predominantly serotonin ceiling effects at doses <150mg daily, with noradrenaline (>150mg daily), and dopamine (>225mg daily) effects becoming more significant as doses are increased.[49],[52]

- Duloxetine demonstrates similar effects.[53],[54] Higher doses are known to cause more adverse drug effects and avoidable harms including insomnia, weight loss and sexual dysfunction.[40],[55],[56]

While in certain conditions it may be appropriate to increase the antidepressant dose, prescribers should always consider limitations of medications and the risks associated with the use of higher doses of medicines. Proactive review of individuals when their condition is stable creates an opportunity to review the need for continued antidepressant treatment regardless of the indication to reduce inappropriate or ineffective antidepressant use.

Chart 2 below shows higher daily doses for individuals on long-term antidepressants (equal to or more than two years), in comparison to those who are on short-term (less than two years) antidepressant therapy.

All antidepressant classes are included. Note TCAs are more commonly prescribed for the treatment of neuropathic pain (e.g. amitriptyline 10mg to 50mg daily, equating to 0.13 to 0.67 DDD) rather than depression (100 to 150mg daily, equating to 1.3 to 2.0 DDD). The majority of SSRIs however, are prescribed for the treatment of depression (e.g. citalopram 20mg to 40mg daily, equating to 1.0 to 2.0 DDD).[57]

Environmental impact

The healthcare industry is increasingly asked to account for the negative climate and environmental impact generated through providing medical care.

In Scotland, every 10 days a 10-tonne truck of medicines waste is transported for incineration. There are associated costs with incineration; travel costs and environment impact (see Figure 4 below). This is in addition to the direct costs of unused medicine.

There are many factors which contribute to medicines waste and a Department of Health and Social Care report in September 2021[58] showed that over prescribing is commonplace, accounting for at least 10% of all prescribed medications.

This guidance supports reducing inappropriate prescribing by recommending person-centred medicine reviews; providing guidance and support for clinicians and promoting the use of non-pharmacological alternatives where available and effective. This may involve physical and social activities, lifestyle change and regular medicine reviews for those with long-term health conditions.

The Royal Pharmaceutical Society policy, ‘Pharmacy’s role in climate action and sustainable healthcare’, [59] identifies medicines as contributing 25% of carbon emissions in the NHS. This can be reduced by:

- improving prescribing and medicines use

- tackling medicines waste

- preventing ill health and

- improving infrastructure and ways of working

The Royal College of General Practitioners[60] has identified that prescribing accounts for over 60% of general practice’s carbon footprint.

Reduction of medicines waste can be achieved by ensuring appropriate prescribing and initiation of medicines, regular person-centred medication reviews to ensure continued effectiveness and deprescribing medicines where appropriate.

Reducing waste from medicines has a double carbon and environmental benefit by:

- reducing upstream emissions, e.g. those associated with distribution, and

- downstream emissions, where fewer medicines need to be disposed of

Medicines that are disposed of in general waste, poured down the sink or flushed down the toilet, increase the risk of environmental harm. Residues from medicines which are unused, not properly disposed of, or from those that pass through the body, can be found in water, soil and sludge and in organisms at all stages of their lifecycles.[61]

Unused or unwanted medicines should be returned to community pharmacy for safe disposal or recycling where available.

The Sustainable Markets Initiative established in 2020 identify seven levers to reduce carbon emissions in care pathways:[62]

1. Decarbonising facilities and fleets

2. Preventing disease onset

3. Diagnosing early

4. Optimising disease management

5. Improving the efficiency of interventions

6. Delivering care remotely or closer to home when appropriate – digital innovations

7. Using lower-emission treatments where available

Pharmaceuticals in the water environment

The Royal Pharmaceutical Society’s Sustainability Policies also point to the occurrence of pharmaceuticals in the water environment.59 Every oral dose of a medicine taken is excreted unchanged or converted to a metabolite with 30-100% entering our wastewater system, which cannot effectively remove all traces. The occurrence of pharmaceuticals in the environment is of global concern and the extent of the risks and impacts on human health and biota is growing. There is already evidence that they can affect aquatic wildlife, increase microbial resistance and enter the human food chain.

The consumption of antidepressants has increased on a global scale and continues to do so. These compounds have been detected in wastewater treatment plants and surface waters, raising concerns about their potential impacts on the environment. After exposure to antidepressants, aquatic life has been found to have behavioural, physical, cardiovascular and reproductive changes. [63]

Current research using estimated risk quotients to predict levels of toxicity to aquatic life indicates that sertraline (RQ4.88), followed by citalopram (RQ 1.55) and bupropion (RQ 1.12) pose the highest known risk from antidepressant therapy to the aquatic environment.63 Research into this area is evolving but highlights the need to prescribe medicines appropriately and consider non-pharmacological interventions where they are available and effective.

There is some existing evidence around the environmental impact of antidepressants globally and the need to ensure appropriate prescribing of antidepressants where indicated, alongside non-pharmacological interventions where available and appropriate.[64] However, a comprehensive Scotland-based environmental profile of antidepressants needs to be developed for use in the Scottish context.

Contact

Email: EPandT@gov.scot

There is a problem

Thanks for your feedback